Abstract

Introduction

Chondroblastoma (also known as Codman tumor) is a rare intermediate grade cartilaginous neoplasm, representing less than 1% of all primary bone tumors; it characteristically arises in the epiphysis or apophysis of a long bone in young patients, predominantly males. The most frequent location of chondroblastoma is the humerus (70% incidence rate) and more rarely it is located in the pelvis. When it affects the hip, the triradiate cartilage is the most common site.

Materials and methods

An unusual case of Chondroblastoma located in the triradiate cartilage is reported. The surgical technique and the imaging are emphasized: a homoplastic fascia latae was used to reconstruct the cartilage layer then a layer of engineered homoplastic bone was superiorly positioned to reconstruct the subchondral bone; the residual cavity was filled with a homoplastic hemi-femoral head concavity molded to best correspond to the acetabular roof and morcelized bone.

Results

At four years of follow-up the patient is pain free and able to walk without crutches; the imaging showed a rearrangement of the trabecula distribution following the lines of force.

Conclusions

The suggested technique could be a valid option in reconstructing acetabular roof in benign lesions. A correct radiological assessment could be helpful for diagnosis and an early detection of local recurrence.

Keywords: Chondroblastoma, Pelvic reconstruction, Bone graft, Triradiate cartilage

1. Introduction

Chondroblastoma is a rare intermediate grade cartilaginous neoplasm, representing less than 1% of all primary bone tumors; it characteristically arises in the epiphysis or apophysis of a long bone in young patients, predominantly males.1 Despite being a rare disease, it is one of the most frequently encountered benign epiphyseal neoplasms in skeletally immature patients. Complications associated with chondroblastoma include pathologic fractures and seldom malignant transformation and pulmonary metastasis.2

Humerus is the most common localization chondroblastoma (70% incidence rate), followed by femur and tibia. In less than 10% of cases chondroblastomas occur in hands and feet. Chondroblastoma is rarely located in the pelvis. When it involves hip, it is more frequently located in the triradiate cartilage.3

Clinical presentation is non-specific and may include joint pain, muscle wasting, tenderness, and swelling or a local mass.

Here, we discuss clinical presentation, workup and treatment of a patient with a chondroblastoma of the acetabulum.

2. Case report

2.1. Clinical presentation

A 17-year-old boy presented to our division complained of pain in his right hip with onset occurring approximately 2 months earlier and aggravated by weight-bearing activities. A pelvic X-ray (Fig. 1a) evidenced a rather well circumscribed osteolytic mass in the right acetabulum. Physical examination revealed intense pain located in his right hip exacerbated by motion. Laboratory test results were unremarcable.

Fig. 1.

A) preoperative X-ray showing a well circumscribed osteolytic lesion in the right acetabulum; B) axial CT scan showed a homogeneous mass eroding the cortical bone without internal calcifications (left side) and with a peripheral contrast enhancement (right side); C) At the MRI, the lesion has a typical signal of cartilage: intermediate on T1-weighted images (right side), with evidence of surrounding edema on STIR sequences (left side).

2.2. Imaging findings

The following CT scan, performed on a 640-slice CT scanner (Aquilion One, Toshiba), showed a large lytic lesion with sclerotic margin, and the absence of internal calcification (Fig. 1b – left side). After contrast medium administration, there was a ready and intense contrast enhancement at the periphery of the lesion (Fig. 1b – right side).

The MRI was performed via a 1.5 T MRI device (GE, Signa Horizon LX) with an 8 Channel Phased Array Coil. The images confirmed the presence of a lobulated tumor with a signal appearance typical of cartilage lesions: intermediate signal on T1-weighted images (Fig. 1c right side), intermediate to high signal on T2 weighted images, with evidence of surrounding edema on STIR sequences (Fig. 1c, left side). On the basis of this clinical picture and the imaging findings, a diagnosis of benign tumor was subsequently hypothesized and the following CT-guided biopsy confirmed the clinical suspicion of chondroblastoma. The biopsy was performed according to the muscular-skeletal oncological rules; after local anesthetic and blade sedation administration, with the patient in supine position an 8G biopsy needle was inserted just 1 cm inferiorly and medially to the anterior superior iliac spine. The track was as lateral as possible to reduce the risk of neurovascular bundles contamination allowing also its removal during definitive surgery.

2.3. Treatment, outcome, follow-up

The patient underwent intralesional excision consisting in curettage with phenol local adjuvant treatment. The operation was performed in supine position; the incision was performed along the anterior 5 cm iliac crest and prolonged medially until the middle of the ileo-inguinal line; the biopsy track was isolated and removed up to the bone level to reduce the risk of local recurrence; to perform the osteotomy of the ileo-pubic eminence and to have access to the disease and curette that, the neurovascular bundles and iliopsoas muscle were transposed medially. Particular attention was paid to not contaminate the little pelvis.

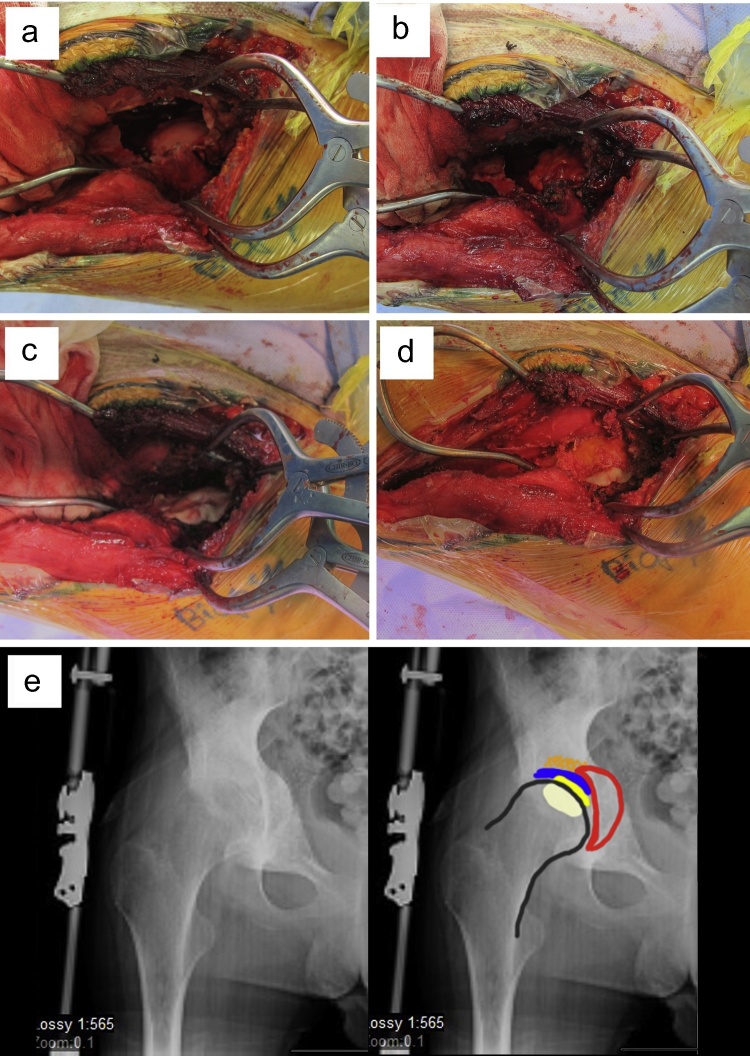

After removal of the tumor, the acetabular roof appeared completely destroyed (Fig. 2a), therefore subsequent reconstruction was performed positioning a triple layer of homoplastic fascia latae in the gap to protect the femoral head (Fig. 2b). A new layer of engineered homoplastic bone was superiorly positioned to reconstruct the subchondral bone (Fig. 2c) and the residual cavity was filled with a homoplastic hemi-femoral head concavity molded to best correspond to the acetabular roof and morcelized bone (Fig. 2d).4, 5

Fig. 2.

A) an intraoperative image showing complete destruction of the acetabular roof after tumor removal: the femoral head is evident; B) the gap in the acetabular roof was reconstructed with a triple layer of homoplastic fascia latae; C) the subchondral bone was reconstructed with a new layer of engineered homoplastic bone; D) the residual gap was filled with a homoplastic femoral head concavely shaped to best adapt to the acetabulum and homoplastic morcelized bone; E) on the left side of the postoperative X-ray; the different reconstruction layers are highlighted in different colors on the right side: yellow-fascia latae, blue-ngineered homoplastic bone, red-homoplastic femoral head, orange-homoplastic morcelized bone.

A pelvic-femoral cast was applied directly in the operating theatre with hip flexed and locked at 0° for 40 days; 0–45° of ROM was allowed for the next two months wearing a hip brace, followed by no restriction. Walking was permitted with crutches bearing no weight for the first three postoperative months; partial weight-bearing (30–50%) was allowed for the following 5 months and after that time complete weight-bearing was permitted.

The postoperative X-ray is shown in Fig. 2e (left side); the reconstruction layers are underlined on the right (Fig. 2e right side). No problems were observed during the postoperative days and as a result the patient was discharged on the fifth post-operative day.

The patient was then followed-up with an X-ray, an MRI and a CT-scan every 4 months for the first year, every 6 months in the second and third year and once a year every following year.

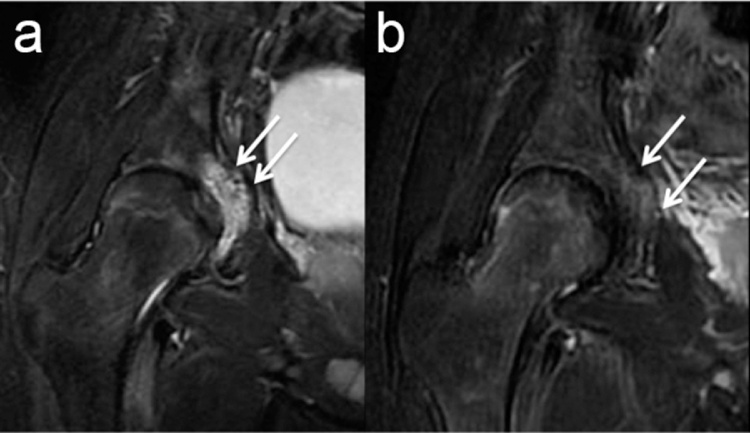

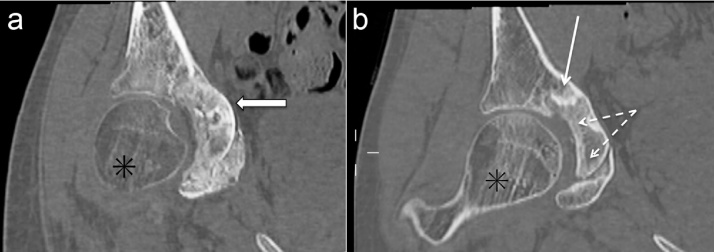

Using this schedule, the evolution of the integration process was documented and local recurrence excluded. Radiographic imaging and CT scans allowed us to examine purely skeletal aspects while MRI scans permitted us to analyze the involvement of adjacent soft tissues and the presence of reactive disorders of the skeletal components. At two months from surgery, we observed all the new components inside the surgical cavity with no evidence of oedema at MRI (Fig. 3a and b). At one year after surgery, we reported blended oedema at the level of the antero-superior side of the acetabular roof probably due to the initial exercises under load performed by the young patient (Fig. 4a, see the arrows); this evidence disappeared after some months (Fig. 4b, see the arrows). During the same period, we started to observe a progressive restoration of bone structure (Fig. 5a and b). In the last X-ray exams, we finally observed new force lines at the level of the acetabular concavity showing skeletal structure repair at that level (Fig. 6).

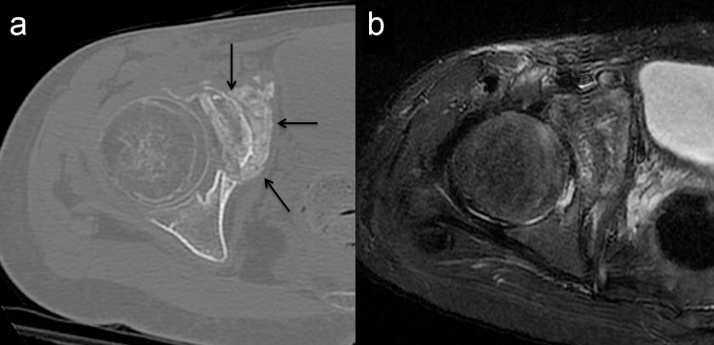

Fig. 3.

CT (A) and MRI T2w Fat Sat (B) at 2 months after surgery. The CT scan shows surgical treatment with the new components of the acetabular roof (arrows); the MRI on the right proves the absence of significant reactive phenomena around the new components.

Fig. 4.

A) MRI performed with coronal images at one year after surgery showed an oedema at the level of the antero-superior side of the acetabular roof probably associated with initial weight-bearing (see the arrows); this evidence disappeared after several months (B, see the arrows).

Fig. 5.

CT with coronal reconstructions (A) 2 months after treatment and (B) 2 years after treatment: (A), black arrow, new acetabular component; (B) integration of new components (dashed arrows) and sclerosis of the weight-bearing bone (continuous white arrow); (*) indicate osteoporosis due to the absence of load in (A) and the restoration of bone density in (B).

Fig. 6.

X-Ray 30 months after surgery; the bone sclerosis and the force lines are similar between the healthy left hip joint and the surgically treated right joint.

At 4 years of follow-up the patient was apparently free of disease, walking without pain even if just mild physical activity was suggested (attached Video 1). The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. No funding was received for the presenting publication; Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

3. Discussion

Chondroblastoma rarely arises in the pelvis but when it does occur the triradiate cartilage is the main site of origin.3

In the present case, the imaging scan was highly suggestive of a benign lesion but a malignant tumor, as Ewing sarcoma had to be excluded. Microscopically chondroblastomas show high cellularity composed of chondroblasts, chondroid matrix, and cartilage with occasional numerous multinucleated cells (which may lead to the incorrect diagnosis of giant cell tumor). Matrix calcification surrounding the chondroblasts, which show a typical polyhedral shape, are arranged in a “chicken-wire calcification” appearance.

the gold-standard treatment is curettage. To reduce recurrence rate, curettage may also be combined with local adjuvant therapy consisting of liquid nitrogen or phenol. Articular surface reconstruction may be necessary in case of extensive subchondral erosion.6

Less commonly chondroblastoma may occur along with metastatic lung disease. In these cases, the nodes have to be completely removed.7

Radiofrequency thermoablation or other minimally invasive radiological techniques can be useful in treating small lesions.8, 9

Surgical management of tumors located in the pelvis poses greater challenges and difficulties, due to the need to protect important neurovascular elements and the immature osteocartilaginous structures in patients who are still growing.

In the present case, the destruction of the acetabular roof was a significant hurdle to overcome. The availability of an engineered homoplastic bone which becomes moldable when heated was helpful because it allowed to perform a roof reconstruction effectively.10

The fascia latae was then used with the intent to reproduce a fibrous layer able to minimize the wear of the femoral head.

The engineered homoplastic bone Plexur M™ was used to reconstruct the first layer of the acetabular roof; it is human bone which is artificially engineered becoming moldable after warmed up, getting hard again after a couple of minutes at body temperature.4, 5 A concave thin layer was so obtained and placed just upon the fascia latae, giving an important support to the roof. Moreover, it is successively substituted by patient bone after a couple of years.

The homoplastic femoral head, accurately concave in shape, provided primary support. During the follow-up, the CT imaging scan demonstrated a progressive restructure of the bone, considering also the weight-bearing zones. In particular, we found that the homoplastic femoral head had successfully integrated with the acetabular bone (Fig. 5a and b).

Conflict of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2017.07.011.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Fletcher C.D.M., Bridge J.A., Hogendoorn P., Mertens F. 4th ed. WHO Press; 2013. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodgers W.B., Mankin H.J. Metastatic malignant chondroblastoma. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 1996;25(12):846–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campanacci M. 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag; Wien, Austria: 1999. Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors: Clinical Features, Imaging, Pathology and Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi B., Zoccali G., Marolda G., Erba F., Zoccali C. Engineering of human bone with Plexur M™ in acetabular roof reconstruction after curettage of a giant aggressive aneurismal bone cyst of the left emypelvis. Minerva Pediatr. 2015;67(1):106–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zoccali C., Anelli V., Chichierchia G., Erba F., Biagini R. The use of engineered biomaterial bone Plexur M® in benign epiphyseal tumors: our experience at 20 months of follow-up. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2014;28(1):65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tiefenboeck T.M., Stockhammer V., Panotopoulos J. Complete local tumor control after curettage of chondroblastoma—a retrospective analysis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102(4):473–478. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2016.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jambhekar N.A., Desai P.B., Chitale D.A., Patil P., Arya S. Benign metastasizing chondroblastoma. Cancer. 1998;11(10):923–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masciocchi C., Zugaro L., Arrigoni F. Radiofrequency ablation versus magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound surgery for minimally invasive treatment of osteoid osteoma: a propensity score matching study. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(8):2472–2481. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masciocchi C., Conchiglia A., Gregori L.M., Arrigoni F., Zugaro L., Barile A. Critical role of HIFU in musculoskeletal interventions. Radiol Med. 2014;119(7):470–475. doi: 10.1007/s11547-014-0414-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zoccali C., Anelli V., Chichierchia G., Erba F., Biagini R. The use of engineered biomaterial Bone Plexur M® in benign epiphyseal tumors: our experience at 20 months of follow-up. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2014;28(1):65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.