Abstract

The survival rate of preterm neonates increases significantly with the development of neonatal care and comprehensive treatment, but more and more high-risk preterm neonates suffer from bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). Currently, there is no effective treatment for BPD, thus it is still a major cause of disability and mortality in neonates. Thus, it is imperative to investigate the pathogenesis and treatment of BPD in depth. Fibroblast growth factor-10 (FGF-10) is a paracrine growth factor binding its receptors (FGFR1 and FGFR2) to regulate a lot of biological processes. FGF-10, with mitotic and chemotactic activities, plays an important role in histogenesis during embryonic stage. It can prevent and attenuate mechanical or infection induced inflammation in lung. Results showed lung FGF-10 expression reduced significantly in neonatal mice with BPD, and exogenous FGF-10 was able to promote the growth of pulmonary mesenchymal stem cells and alveolar epithelial cells type II and reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. We preliminarily explored the relationship between FGF-10 and NF-κB in this animal model and found FGF-10 could inhibit NF-κB p65 expression as a feedback. Thus, to investigate the protective effects of FGF-10 on hyperoxia induced BPD in neonatal mice will provide a new strategy for the treatment of BPD.

Keywords: Fibroblast growth factor-10, hyperoxia, bronchopulmonary dysplasia

Introduction

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a chronic lung disease (CLD) often found in preterm neonates after long lasting exposure to hyperoxia and/or mechanical ventilation. The incidence of BPD is 12.3%-30.0% in preterm neonate with a gestational age of <32 weeks [1]. BPD may compromise lung function and increase the risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, early-onset emphysema, and neurological disorders [2]. The survival rate of preterm neonates increases over time with the development of neonatal care, prenatal use of steroids for lung maturation, treatment with pulmonary surfactant, improvement of strategies for mechanical ventilation and other comprehensive therapies, but the preterm neonates with high risk for BPD increase [3]. Currently, BPD is mainly treated by mechanical ventilation and pharmacotherapy, but the therapeutic efficacy is still unsatisfactory. BPD is still a major cause of mortality and disability. Thus, it is imperative to investigate the pathogenesis and treatments of BPD in depth.

It has been shown that fibroblast growth factor-10 (FGF-10) is able to regulate the morphogenesis of lung structure in the early stage of lung development [4]. FGF-10, also known as keratinocyte growth factor-2 (KGF-2), is a member of FGF family and belongs to the FGF-7 subfamily [5]. FGF-10 is an alkaline protein that is composed of 84-246 amino acids and has the molecular weight of 20 kDa. It is mainly expressed on embryonic epithelium, interstitial cells, and fibroblasts as well as in the adult liver, lung and intestine. FGF-10 via paracrine binds heparan sulfate to activate FGFR1 and FGFR2 [6], which then regulates different biological processes. FGF-10 is a paracrine growth factor and plays important roles in the limb bud development [7], palate development [8], directional growth of lung bud [9], otocyst morphogenesis [10], adipogenesis [11], and the development of adrenal gland [12], breast [13], lacrimal gland [14] and submandibular gland. There is evidence showing that FGF-10 may prevent and attenuate the mechanical or infection induced lung injury. Thus, to investigate the protective effects of FGF-10 on the hyperoxia induced lung injury in neonatal mice will provide evidence for the treatment of BPD.

To further understand the role of FGF-10 in BPD, a BPD model was established in neonatal mice, and the FGF-10 expression was detected in the lung of BPD mice. In addition, lung cells were cultured in vitro. The influence of FGF-10 in the medium on the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, lung mesenchymal stem cells, and alveolar epithelial cells type II was further investigated, and the relationship between FGF-10 and NF-κB was also evaluated.

Materials and methods

Animals and reagent

Kunming mice were purchased from the Military Academy of Medical Sciences. Recombinant mouse FGF-10 (R&D Systems Inc, USA), rabbit anti-mouse FGF-10 polyclonal antibody (Abnova, USA), anti-mouse CD29 monoclonal antibody (PE), anti-mouse CD105 monoclonal antibody (PE), anti-mouse CD90 monoclonal antibody (FITC), anti-mouse CD34 monoclonal antibody (FITC) (BD Pharmingen), SPC antibody (Abcam, UK) and NF-κB p65 antibody (Cell signaling technology, USA) were used in the present study.

Establishment of hyperoxia induced BPD model in neonatal mice

2 days old Kunming mice (n=80) were randomly divided into hyperoxia group (the oxygen concentration was maintained at 60-70%) and air group (n=40 per group). In hyperoxia group, mice were placed in man-made box with sodium lime on the bottom for the absorbance of CO2; the box temperature was maintained at 22-26°C, humidity at 50-60% and CO2 concentration <0.5%. The neonates were housed with mother mice, and mother mice were exchanged every day. Mice were exposed to hyperoxia for 21 days. On day 4, 7 and 14, 6 mice in each group were sacrificed, and the lung was collected and then stored at -80°C or fixed in 10% paraformaldehyde for further usage. On day 21, the remaining mice were sacrificed, and cells were separated, or lung tissues were stored at -80°C or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for further usage. The whole study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Army General Hospital of People’s Liberation Army, and all the procedures were done according to the Animal Care and Use guideline.

H&E staining and immunohistochemistry

The lung tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in a series of ethanol, then embedded in paraffin and sectioned (4 μm). Sections were stored at room temperature and then H&E staining was performed as follows: Sections were treated with xylene and then a series of ethanol. After washing in distilled water, Hematoxylin was used to stain nucleus and eosin to stain cytoplasm. After dehydration and mounting, sections were observed under a light microscope and representative photographs were captured. Immunohistochemistry was performed as follows: sections were subjected to antigen retrieval, blocking of endogenous peroxidase, blocking in BAS, incubation with primary antibody (mouse FGF-10 antibody or NF-κB p65 antibody) and then with secondary antibody, visualization with DAB, staining of nucleus, dehydration, and mounting. Sections were then observed under a microscope, and representative photographs were captured.

RT-PCR

The lung tissues were grounded in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent according to manufacturer’s instruction. Then, total RNA was subjected to reverse transcription into cDNA (Promega), followed by RT-PCR. The mixture for PCR was prepared. The fluorescence signal was captured during RT-PCR, and the data were automatically calculated by a computer.

Western blotting

Lung tissues or lung cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer for 30 min on ice. Then, 2×SDS-PAGE Loading Buffer of equal volume was added. Proteins were denatured by boiling. Then, the proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred onto PVDF membrane. After blocked in non-fat milk, the membrane was incubated with primary antibody (1:1000; mouse FGF-10 antibody or NF-κB p65 antibody) at 4°C over night. β-actin served as an internal reference. Then, the membrane was treated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG for 1 h, followed by visualization.

Culture of lung cells

Mice were sacrificed by decapitation and then sterilized with 75% ethanol. Under an aseptic condition, thoracotomy was performed and the lung tissues were harvested. The tracheal and bronchial tissues were removed, and the lung tissues were washed with PBS to remove blood cells. Then, the lung tissues were cut into blocks (0.3 mm3) and filtered through 100-mesh filter to prepare single cell suspension. Then, the cell suspension was added to dishes and cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (with or without 100 ng/mL FGF-10). Cells were divided into air group, air +FGF-10 group, hyperoxia group and hyperoxia +FGF-10 group. Cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified environment with 5% CO2. The medium was refreshed after 24 h to remove suspended cells. Then, the medium was refreshed twice weekly.

Flow cytometry

When the cell confluence reached 70-80%, cells were digested with trypsin and then harvested by centrifugation. After washing in PBS once, cells were re-suspended in 10-20 μl of PBS with 2.5×105 cells per sample. These cells were incubated with CD29CD90 antibodies or CD34+CD105 antibodies in dark for 30 min at room temperature. After these cells were washed in PBS twice, flow cytometry was performed.

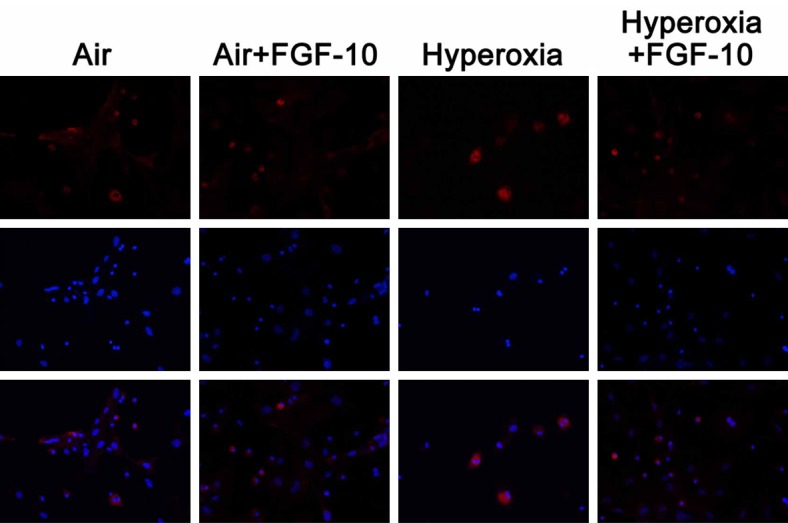

Immunofluorescence staining

The coverslips were added to 6-wells plates and cell suspension was added to the coverslips. Then, cells were maintained in DMEM at 37°C in an environment with 5% CO2. When the cell confluence reached 70-80%, the medium was removed, and cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. After washed in PBS thrice, cell membrane was permeabilized, and then cells were incubated with primary antibodies (SP-C antibody or NF-κB p65 antibody) at 4°C over night. After washing, cells were treated with secondary antibody in dark at room temperature for 50 min. The nucleus was stained with DAPI, followed by mounting. Cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope, and representative photographs were captured.

ELISA

Cell medium collected 4, 7 and 10 days after culture was thawed and centrifuged at 2000-3000 rpm/min for 20 min. The supernatant was collected and the contents of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MIP-2, and TGF-β were detected by ELISA according to manufacturer’s instruction. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm (OD) and the standard deviation was delineated. The sample concentration was calculated on the basis of standard deviation and histogram was delineated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS version 22.0. Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (X±S) and comparisons were done with independent t test. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Successful establishment of hyperoxia-induced BPD in neonatal mice

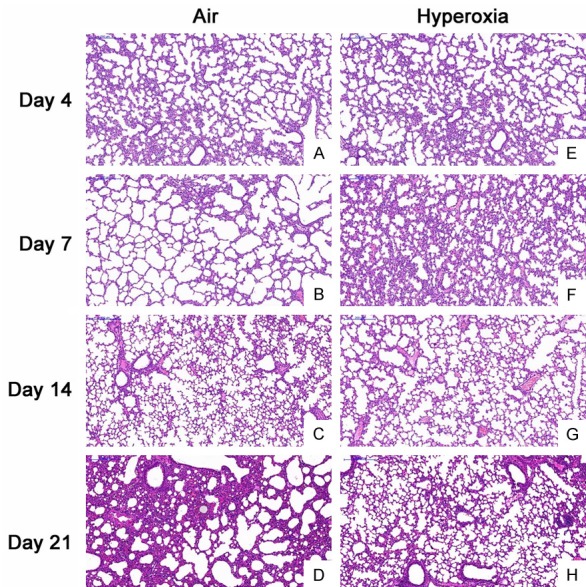

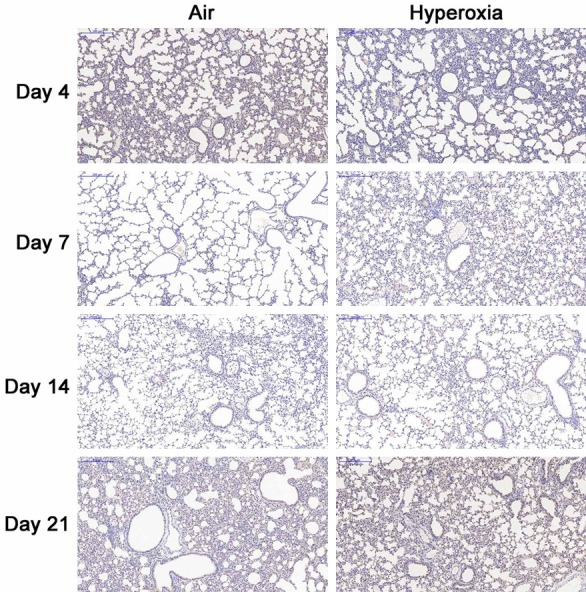

No mice died during the establishment of hyperoxia induced BPD. 7 days after birth, the health status was comparable between two groups. 14 days after birth, mice in hyperoxia group showed poor spirit, rough and disheveled hair without luster, less activity and became anxious after discontinuation of hyperoxia exposure. 21 days after birth, the mice in hyperoxia group showed significantly small size, rough and disheveled hair and presented anxiousness, shortness of breath and cyanosis of the lip and toes immediately after discontinuation of hyperoxia exposure. In air exposure group, mice showed good growth, lustered hair, good response to stimulation and favorable activity. At the beginning of the study, there was no significant difference in body weight between two groups, but the body weight in hyperoxia group and air group was 16.7±1.44 g and 22.2±1.81 g, respectively, showing significant difference (t=-11.187, P<0.001). H&E staining showed the alveolar septa were even in air group (Figure 1A-D). In hyperoxia group, the lung structure showed typical features of BPD: alveolar septa were thickened and there were hemorrhage and infiltration of inflammatory cells in early phase; the number of alveoli reduced, some alveoli merged, and some alveoli showed inflammatory atelectasis (Figure 1E-H). These findings suggested that hyperoxia-induced BPD was successfully established.

Figure 1.

Lung pathology at different time points in both groups (H&E staining, 200×). A-D: The alveolar sepata were even and there was no exudation in air group; E, F: There was alveolar septum thickening, hemorrhage and infiltration of inflammatory cells; G, H: The alveolar structure was irregular, the alveolar space was enlarged, some alveoli merged, the number of alveoli reduced, and some alveoli showed inflammatory atelectasis.

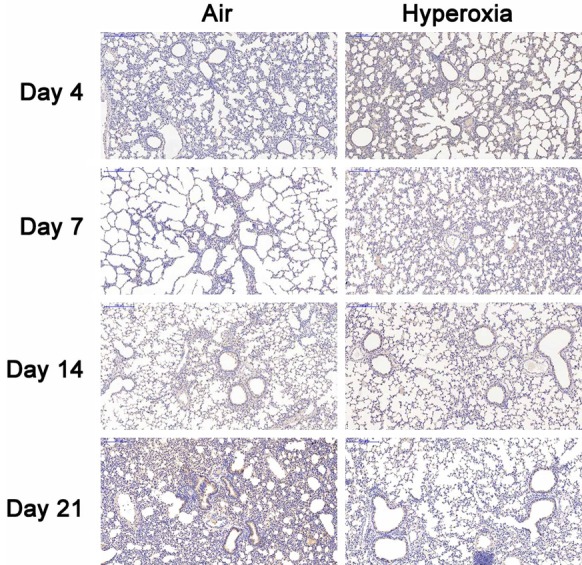

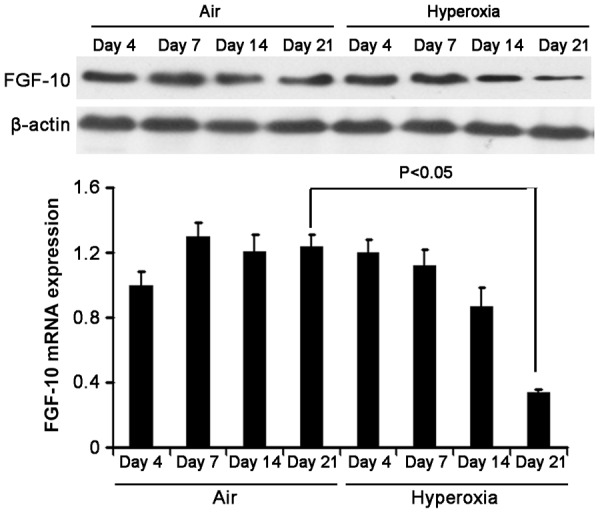

Decreased FGF-10 expression in neonatal mice with hyperoxia-induced BPD

To investigate the role of FGF-10 in BPD, the FGF-10 expression was firstly detected in the lung of mice with hyperoxia-induced BPD. 4, 7, 14 and 21 days after hyperoxia exposure, immunohistochemistry was done for FGF-10 in the lung. Results showed no significant difference in FGF-10 expression 4, 7 and 14 days after hyperoxia exposure between two groups. However, on day 21, the FGF-10 expression in hyperoxia group was significantly lower than in air group (Figure 2). Furthermore, we detected the FGF-10 expression by RT-PCR and Western blotting. Results showed no significant difference in FGF-10 expression 4, 7 and 14 days after hyperoxia exposure, but it was significantly lower than in air group on day 21 in hyperoxia group (P<0.05). Western blotting showed the FGF-10 expression in hyperoxia group reduced over time, but it remained unchanged in air group (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemistry for FGF-10 in the lung of hyperoxia group and air group (DAB×100). The lung was collected at different time points and processed for immunohistochemistry. On day 4, 7 and 14, there was no significant difference in FGF-10 expression between two groups. On day 21, the FGF-10 expression in hyperoxia group was significantly lower than that in air group.

Figure 3.

FGF-10 expression in the lung of hyperoxia group and air group. At different time points, the lung was collected for the detection of mRNA and protein expression of FGF-10 by RT-PCR and Western blotting after extraction of total RNA. Results showed, on day 4, 7 and 14, FGF-10 expression was comparable between two groups; on day 21, the FGF-10 mRNA expression in hyperoxia group reduced significantly when compared with air group (*P<0.05). Western blotting showed FGF-10 expression in the lung of hyperoxia group decreased over time.

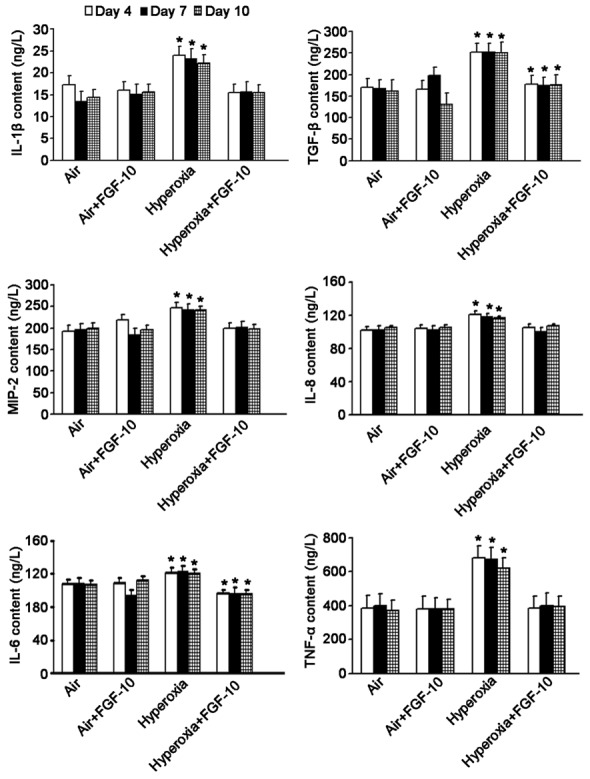

Exogenous FGF-10 is able to reduce the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in lung cells

In the hyperoxia induced BPD mice, results showed FGF-10 expression reduced in the lung, which was consistent with the findings that FGF-10 expression reduced in BPD neonates in clinical practice. Thus, it was speculate that exogenous FGF-10 might improve BPD to a certain extent. In the following experiment, lung cells were divided into air group, air +FGF-10 group, hyperoxia group, and hyperoxia +FGF-10 group. 4, 7 and 10 days after culture, the medium was harvested for the detection of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MIP-2, and TGF-β by ELISA. Detection was done thrice, and mean values were calculated. Results showed the contents of these pro-inflammatory cytokines were comparable between air group and air +FGF-10 group. However, in hyperoxia group, the contents of these cytokines increased significantly when compared with air group (P<0.05). When compared with air group, IL-6 content reduced significantly (P<0.05) and TGF-β content increased significantly (P<0.05) in hyperoxia +FGF-10 group, but there were no significant differences in the contents of IL-1β, IL-8, MIP-2, and TNF-α between air group and hyperoxia +FGF-10 group (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Contents of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the medium of lung cells (ELISA). When compared with air group, the contents of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MIP-2 and TGF-β increased significantly in hyperoxia group (*P<0.05). When compared with air group, IL-6 content reduced markedly (*P<0.05) and TGF-β content increased significantly (*P<0.05) in hyperoxia +FGF-10 group, but there were no significant differences in the contents of IL-1β, IL-8, MIP-2 or TNF-α between air group and hyperoxia +FGF-10 group.

FGF-10 is able to promote the growth of pulmonary mesenchymal stem cells and alveolar epithelial cells type II

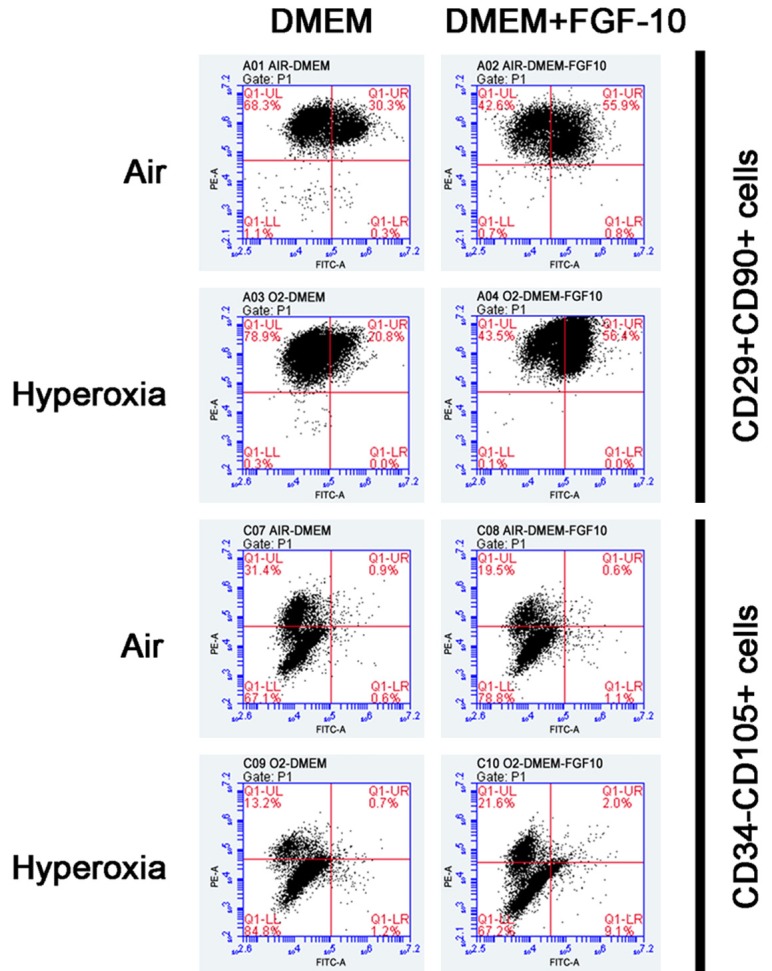

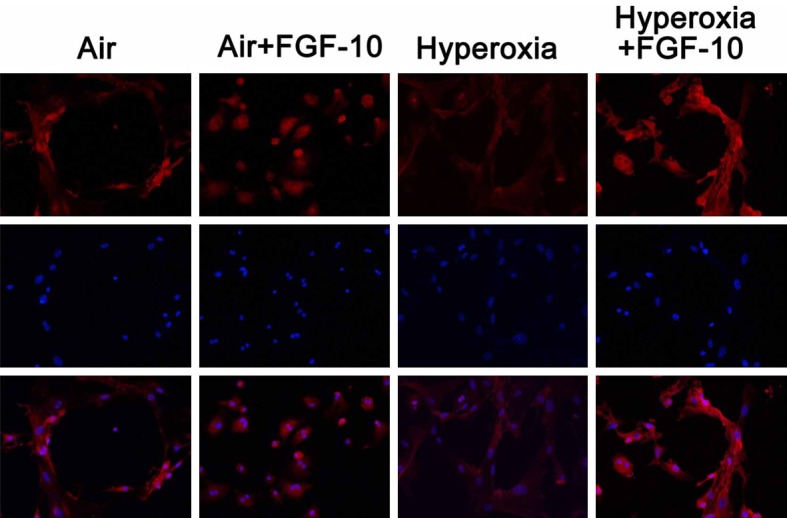

Results showed exogenous FGF-10 was able to reduce the contents of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the supernatant of lung cells after hyperoxia exposure, which suggested that FGF-10 was able to attenuate hyperoxia induced inflammation. In the following experiment, the effects of FGF-10 on the growth of pulmonary mesenchymal stem cells and alveolar epithelial cells type II were further investigated. Cells were divided into air group, air +FGF-10 group, hyperoxia group, and hyperoxia +FGF-10 group. Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence staining were performed. Pulmonary mesenchymal stem cells are CD34-CD29+CD90+CD105+. Thus, CD29+CD90+ cells and CD34-CD105+ cells were detected in 4 groups. Results showed the proportion of CD29+CD90+ cells was the lowest in hyperoxia group, but addition of FGF-10 during hyperoxia (hyperoxia +FGF-10 group) significantly increased the proportion of CD29+CD90+ cells which was even higher than that in air group. The proportion of CD34-CD105+ cells remained unchanged in 4 groups (Figure 5). This suggested that FGF-10 was able to promote the growth of CD29+CD90+ pulmonary mesenchymal stem cells. Furthermore, immunohistochemistry staining was done for SP-C, a marker of alveolar epithelial cells type II. Results showed the SP-C expression was comparable between air group and air +FGF-10 group, but SP-C expression reduced significantly in hyperoxia group as compared with air group, and addition of FGF-10 could significantly increase SP-C expression in hyperoxia +FGF-10 group (Figure 6), indicating that FGF-10 was able to enhance the growth of alveolar epithelial cells type II.

Figure 5.

Detection of lung cell marker (Flow cytometry). The proportion of CD29+CD90+ cells in air group, air +FGF-10 group, hyperoxia group and hyperoxia +FGF-10 group was 30.3%, 55.9%, 20.8% and 56.4%, respectively, and that of CD34-CD105+ cells was 98.5%, 98.3%, 98.0% and 88.8%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence staining of SP-C in lung cells (200×). SP-C expression was comparable between air group and air +FGF-10 group, but SP-C expression reduced in hyperoxia group, and addition of FGF-10 significantly increased SP-C expression in hyperoxia +FGF-10 group.

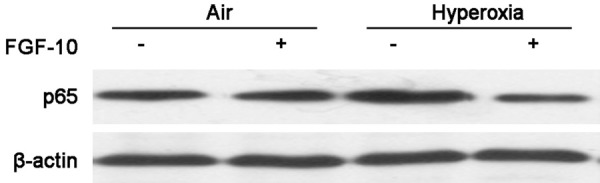

NF-κB signaling pathway is an important pathway in the inflammation, and NF-κB is able to suppress FGF-10 expression. In this study, above results showed FGF-10 was able to reduce the expression of pro-inflamamtory cytokines. Thus, it was speculated that FGF-10 wass able to inhibit NF-κB expression in a feedback manner. p65 is a key component of NF-κB. To confirm this hypothesis, immunohsitocehmsitry was done to detect p65 expression in the lung of mice 4, 7, 14 and 21 days after hyperoxia exposure, and Western blotting was done to detect NF-κB p65 expression in lung cells with or without FGF-10 treatment. Immunnohistochemistry showed, the NF-κB p65 expre-ssion on day 4 and 7 were similar between air group and hyperoxia group. However, on day 14 and 21, the NF-κB p65 expression increased significantly in hyperoxia group as compared with air group (Figure 7). Western blotting indicated addition of FGF-10 had no significant influence on the NF-κB p65 expression in lung cells exposed to air. However, addition of FGF-10 in cells experiencing hyperoxia exposure significantly reduced the NF-κB p65 expression as compared with hyperoxic cells without FGF-10 treatment, and the NF-κB p65 expression in hyperoxia +FGF-10 group was comparable to that in air group (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

NF-κB p65 expression in the lung cells exposured to air and hyperoxia (Imunohistochemistry; DAB×100). When compared with air group, the NF-κB p65 expression in hyperoxia group remained unchanged on day 4 and 7. However, on day 14 and 21, the NF-κB p65 expression increased significantly in hyperoxia group when compared with air group.

Figure 8.

NF-κB p65 expression in lung cells with or without FGF-10 treatment after air or hyperoxia exposure (Western blotting).

Lung cells exposed to air or hyperoxia were maintained in medium with or without FGF-10, and NF-κB p65 expression was detected 2 weeks later. Addition of FGF-10 did not affect the NF-κB p65 expression in air group. In hyperoxia group, NF-κB p65 expression increased significantly when compared with air group, but the addition of FGF-10 significantly reduced NF-κB p65 expression in hyeperoxia +FGF-10 group as compared with hyperoxia group.

Immunofluorescence staining was done to detect NF-κB p65 expression in lung cells with or without FGF-10 treatment after air or hyperoxia exposure. Immunofluorescence staining showed the NF-κB p65 expression was at a low level in air group and addition of FGF-10 had no significant influence on NF-κB p65 expression. In hyperoxia group, NF-κB p65 expression increased significant when compared with air group, but addition of FGF-10 in hyperoxia group markedly reduced NF-κB p65 expression and it in hyperoxia +FGF-10 group was similar to that in air group (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Influence of FGF-10 on the NF-κB p65 expression in lung cells with or without FGF-10 treatment after exposure to air or hyperoxia (Immunofluorescence staining; 200×). NF-κB p65 expression was at a low level in air group and air +FGF-10 group and there was no significant difference between them. In hyperoxia group, NF-κB p65 expression increased significantly, and addition of FGF-10 markedly reduced NF-κB p65 expression in hyperoxia +FGF-10 group.

Discussion

BPD is a lung disease with high morbidity in preterm neonates. Classical BPD was firstly reported and defined by Northway et al in 1967 [15]. In recent years, a new type of BPD, also known as mild BPD, is proposed, but BPD is still the most common complication of premature delivery. Neonates with BPD often develop sequelae of respiratory system [16-19] and nervous system [20,21]. Thus, to deeply investigate the pathogenesis of BPD and to explore the effective therapies for BPD have been hot topics in recent studies. Of note, a good animal model is indispensable for the investigations on BPD. To date, several animal models have been developed for the investigations of BPD, and the hyperoxia-induced BPD animal model is the most common one. Simple hyperoxia exposure may induce the classic pathology of BPD [22]. In practice, exposure to 60-70% oxygen will cost a long time to induce BPD, but the mortality is low, which is more clinically practical. Thus, in the present study, neonatal mice were exposed to 60-70% oxygen. In the available studies, several types of animals such as baboons, sheep, pigs, rabbits and rodents have been employed for establishment of the BPD animal model. In the present study, the BPD model was established in neonatal mice based on the requirement of subsequent experiment. The lung development of neonatal mice is similar to that in humans, and the time from birth to 28 days after birth is a key stage in the lung development of neonatal mice. The lung development at this stage is similar to that from gestational age of 28 weeks to 36 months after birth in humans [23]. In this study, 2 days old Kunming mice were exposed to hyperoxia, which can effectively mimic the clinical characteristics of new type of BPD. The clinical features and pathological findings from H&E staining in neonatal mice after hyperoxia suggested that the BPD animal model was successfully established in neonatal mice.

FGF-10 is an interstitial marker expressed at terminal interstitium. FGF-10 can act on adjacent epithelial cells expressing fibroblast growth factor receptor 2-IIIb (FGFR2b) to maintain the progenitor cell-like state of epithelial cells and induce the branch formation [24-27]. In the embryonic lung development, when soluble dominantly inactive FGFR2 is over-expressed, branching morphogenesis is inhibited [28], indicating that FGF-10 plays an important role in the lung development. Some investigators found FGF-10 positive cells reduced in BPD children when compared with controls [29], indicating that FGF-10 expression reduced in BPD patients. This is also consistent with findings of this study that FGF-10 expression in the lung reduced in neonatal mice with hyperoxia induced BPD. RT-PCR further confirmed the FGF-10 mRNA expression reduced in the lung of mice after hyperoxia exposure. These findings implied that FGF-10 was closely related to the pathogenesis of BPD. Thus, it was speculate that exogenous FGF-10 might protect the lung against hyperoxia-induced BPD. In recent years, studies have shown that FGF-10 is able to prevent lung injuries caused by several factors (including bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis [30], high altitude pulmonary edema [31], LPS induced lung injury [32], mechanical ventilation induced lung injury [33], and ischemia/reperfusion induced lung injury [34]). In addition, there was evidence showing that FGF-10 was able to mobilize lung-resident mesenchymal stem cells (LR-MSCs) to protect against acute lung injury [35]. We investigated the relationship between FGF-10 and mesenchymal stem cells in hyperoxia induced lung injury, and results showed FGF-10 was able to increase the proportion of CD29 and CD90 double positive mesenchymal stem cells in lung cells after hyperoxia exposure, indicating that FGF-10 may promote the growth of mesenchymal stem cells, which may contribute to the repair of lung injury after hyperoxia exposure.

FGF-10 is an effective mitogen for alveolar epithelial cells and play crucial roles in the organ morphogenesis and epithelial differentiation. Pre-clinical and clinical studies have shown that FGF-10 has the promise to become a new alternative for the treatment of alveolar epithelial injury in ALI/ARDS [36]. Thus, we detected the effects of FGF-10 on hyperoxia induced injury to lung epithelial cells. SP-C is an important marker of alveolar epithelial cells type II. Thus, we detected SP-C expression to indirectly reflect the repair of alveolar epithelial cells type II after hyperoxia exposure. Immunofluorescence staining showed hyperoxia could significantly reduce SP-C expression, but addition of FGF-10 significantly increased the SP-C expression in lung cells after hyperoxia exposure indicating that FGF-10 may promote the growth of alveolar epithelial cells type II, which contributes to the repair of alveolar epithelial cells after hyperoxia exposure.

Inflammation and host immune response play a pivotal role in the pathology of BPD. Chorioamnionitis induced prenatal inflammation is closely related to the increased risk for BPD in infants [37]. Thus, it was speculated that whether FGF-10 was able to attenuate inflammation. In this study, ELISA was performed to detect the content of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MIP-2 and TGF-β) in the medium. Results showed hyperoxia could significantly increase the pro-inflammatory cytokines after lung injury, but addition of FGF-10 reversed the hyperoxia induced increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines, implying that FGF-10 may attenuate inflammation to repair lung injury after hyperoxia exposure. NF-κB is a central participant in the inflammation related signaling pathway and has been found to be involved in the inflammation, immune response, and regulation of cell differentiation and apoptosis [38]. NF-κB is indispensable for the pathogenesis of inflammation related lung injury. Thus, we further investigated the relationship between FGF-10 and NF-κB. Studies have shown that NF-κB p65 (a key component of NF-κB) expression increased significantly in the lung of BPD animals, but FGF-10 expression decreased significantly [29,39]. Further investigation revealed that the interaction between NF-κB p65 and PS3 was able to inhibit SP1 mediated FGF-10 expression [40]. Immunohistochemistry in this study showed NF-κB p65 expression was increased significantly in the lung of mice with hyperoxia-induced BPD, which was consistent with above findings. In addition, addition of FGF-10 in lung cells after hyperoxia exposure reduced NF-κB p65 expression, indicating that FGF-10 might inhibit NF-κB p65 in a feedback manner, which attenuated inflammation and then promoted the lung repair in neonatal mice after hyperoxia-induced BPD. However, the specific mechanism is warranted to be studied in depth.

Taken together, a hyperoxia-induced BPD model was successfully established in the present study, and the FGF-10 expression in the lung was detected in neonatal mice with BPD. In addition, the relationship of FGF-10 with lung mesenchymal stem cells, alveolar epithelial cells type II and pro-inflammatory cytokines was investigated, and the correlation between FGF-10 and NF-κB was also explored. These findings will provide evidence for the further investigations about the pathogenesis and treatment of BPD.

Conclusion

BPD is still an important disease threatening the health of preterm neonates significantly, and has been a determinant of lung diseases in children and adults. BPD may cause lifelong lung diseases and confer adverse effects on economic and quality of life of patients. Thus, more attention should be paid to the prevention of these lung diseases. This study provides new evidence for the lung repair following BPD, and also presents experimental basis for the therapy of BPD and the prevention of its long-term sequelae.

Acknowledgements

We thank Long Cheng (associate researcher) in the Military Academy of Medical Sciences and Xing Zhang (Associate Professor) in the Forth Military Medical University for their advice and help.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Guaman MC, Gien J, Baker CD, Zhang H, Austin ED, Collaco JM. Point prevalence, clinical characteristics, and treatment variation for infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32:960–967. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1547326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Reilly M, Sozo F, Harding R. Impact of preterm birth and bronchopulmonary dysplasia on the developing lung: long-term consequences for respiratory health. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40:765–773. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1723–1729. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellusci S, Grindley J, Emoto H, Itoh N, Hogan BL. Fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10) and branching morphogenesis in the embryonic mouse lung. Development. 1997;124:4867–4878. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beenken A, Mohammadi M. The FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:235–253. doi: 10.1038/nrd2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Ibrahimi OA, Olsen SK, Umemori H, Mohammadi M, Ornitz DM. Receptor specificity of the fibroblast growth factor family. The complete mammalian FGF family. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15694–15700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601252200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Min H, Danilenko DM, Scully SA, Bolon B, Ring BD, Tarpley JE, DeRose M, Simonet WS. Fgf-10 is required for both limb and lung development and exhibits striking functional similarity to Drosophila branchless. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3156–3161. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice R, Spencer-Dene B, Connor EC, Gritli-Linde A, McMahon AP, Dickson C, Thesleff I, Rice DP. Disruption of Fgf10/Fgfr2bcoordinated epithelial-mesenchymal interactions causes cleft palate. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1692–1700. doi: 10.1172/JCI20384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weaver M, Dunn NR, Hogan BL. Bmp4 and Fgf10 play opposing roles during lung bud morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:2695–2704. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.12.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pirvola U, Spencer-Dene B, Xing-Qun L, Kettunen P, Thesleff I, Fritzsch B, Dickson C, Ylikoski J. FGF/FGFR-2(IIIb) signaling is essential for inner ear morphogenesis. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6125–6134. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06125.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakaue H, Konishi M, Ogawa W, Asaki T, Mori T, Yamasaki M, Takata M, Ueno H, Kato S, Kasuga M, Itoh N. Requirement of fibroblast growth factor 10 in development of white adipose tissue. Genes Dev. 2002;16:908–912. doi: 10.1101/gad.983202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donjacour AA, Thomson AA, Cunha GR. FGF-10 plays an essential role in the growth of the fetal prostate. Dev Biol. 2003;261:39–54. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mailleux AA, Spencer-Dene B, Dillon C, Ndiaye D, Savona-Baron C, Itoh N, Kato S, Dickson C, Thiery JP, Bellusci S. Role of FGF10/FGFR2b signaling during mammary gland development in the mouse embryo. Development. 2002;129:53–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makarenkova HP, Ito M, Govindarajan V, Faber SC, Sun L, McMahon G, Overbeek PA, Lang RA. FGF10 is an inducer and Pax6 a competence factor for lacrimal gland development. Development. 2000;127:2563–2572. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.12.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Northway WH Jr, Rosan RC, Porter DY. Pulmonary disease following respirator therapy of hyaline-membrane disease. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 1967;276:357–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196702162760701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhandari A, Bhandari V. Pathogenesis, pathology and pathophysiology of pulmonary sequelae of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants. Front Biosci. 2003;8:e370–380. doi: 10.2741/1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolton CE, Stocks J, Hennessy E, Cockcroft JR, Fawke J, Lum S, McEniery CM, Wilkinson IB, Marlow N. The EPICure study: association between hemodynamics and lung function at 11 years after extremely preterm birth. J Pediatr. 2012;161:595–601. e592. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gough A, Spence D, Linden M, Halliday HL, McGarvey LP. General and respiratory health outcomes in adult survivors of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a systematic review. Chest. 2012;141:1554–1567. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narang I. Review series: what goes around, comes around: childhood influences on later lung health? Long-term follow-up of infants with lung disease of prematurity. Chron Respir Dis. 2010;7:259–269. doi: 10.1177/1479972310375454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Short EJ, Kirchner HL, Asaad GR, Fulton SE, Lewis BA, Klein N, Eisengart S, Baley J, Kercsmar C, Min MO, Singer LT. Developmental sequelae in preterm infants having a diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: analysis using a severity-based classification system. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:1082–1087. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Short EJ, Klein NK, Lewis BA, Fulton S, Eisengart S, Kercsmar C, Baley J, Singer LT. Cognitive and academic consequences of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and very low birth weight: 8-year-old outcomes. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e359. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.e359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Wang H, Shi Y, Peng W, Zhang S, Zhang W, Xu J, Mei Y, Feng Z. Role of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the prevention of hyperoxia-induced lung injury in newborn mice. Cell Biol Int. 2012;36:589–594. doi: 10.1042/CBI20110447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth-Kleiner M, Post M. Similarities and dissimilarities of branching and septation during lung development. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40:113–134. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu J, Izvolsky KI, Qian J, Cardoso WV. Identification of FGF10 targets in the embryonic lung epithelium during bud morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4834–4841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park WY, Miranda B, Lebeche D, Hashimoto G, Cardoso WV. FGF-10 is a chemotactic factor for distal epithelial buds during lung development. Dev Biol. 1998;201:125–134. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters K, Werner S, Liao X, Wert S, Whitsett J, Williams L. Targeted expression of a dominant negative FGF receptor blocks branching morphogenesis and epithelial differentiation of the mouse lung. Embo J. 1994;13:3296–3301. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekine K, Ohuchi H, Fujiwara M, Yamasaki M, Yoshizawa T, Sato T, Yagishita N, Matsui D, Koga Y, Itoh N, Kato S. Fgf10 is essential for limb and lung formation. Nat Genet. 1999;21:138–141. doi: 10.1038/5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hokuto I, Perl AK, Whitsett JA. Prenatal, but not postnatal, inhibition of fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling causes emphysema. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:415–421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benjamin JT, Smith RJ, Halloran BA, Day TJ, Kelly DR, Prince LS. FGF-10 is decreased in bronchopulmonary dysplasia and suppressed by Toll-like receptor activation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L550–558. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00329.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupte VV, Ramasamy SK, Reddy R, Lee J, Weinreb PH, Violette SM, Guenther A, Warburton D, Driscoll B, Minoo P, Bellusci S. Overexpression of fibroblast growth factor-10 during both inflammatory and fibrotic phases attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:424–436. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200811-1794OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.She J, Goolaerts A, Shen J, Bi J, Tong L, Gao L, Song Y, Bai C. KGF-2 targets alveolar epithelia and capillary endothelia to reduce high altitude pulmonary oedema in rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:3074–3084. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tong L, Bi J, Zhu X, Wang G, Liu J, Rong L, Wang Q, Xu N, Zhong M, Zhu D, Song Y, Bai C. Keratinocyte growth factor-2 is protective in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2014;201:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bi J, Tong L, Zhu X, Yang D, Bai C, Song Y, She J. Keratinocyte growth factor-2 intratracheal instillation significantly attenuates ventilator-induced lung injury in rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:1226–1235. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang X, Wang L, Shi L, Chen C, Wang Q, Bai C, Wang X. Protective effects of keratinocyte growth factor-2 on ischemia-reperfusion-induced lung injury in rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;50:1156–1165. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0268OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong L, Zhou J, Rong L, Seeley EJ, Pan J, Zhu X, Liu J, Wang Q, Tang X, Qu J, Bai C, Song Y. Fibroblast growth factor-10 (FGF-10) mobilizes lung-resident mesenchymal stem cells and protects against acute lung injury. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21642. doi: 10.1038/srep21642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang X, Bai C, Wang X. Potential clinical application of KGF-2 (FGF-10) for acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2010;3:797–805. doi: 10.1586/ecp.10.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watterberg KL, Demers LM, Scott SM, Murphy S. Chorioamnionitis and early lung inflammation in infants in whom bronchopulmonary dysplasia develops. Pediatrics. 1996;97:210–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiscott J, Kwon H, Genin P. Hostile takeovers: viral appropriation of the NF-kappaB pathway. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:143–151. doi: 10.1172/JCI11918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benjamin JT, Carver BJ, Plosa EJ, Yamamoto Y, Miller JD, Liu JH, van der Meer R, Blackwell TS, Prince LS. NF-kappaB activation limits airway branching through inhibition of Sp1-mediated fibroblast growth factor-10 expression. J Immunol. 2010;185:4896–4903. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carver BJ, Plosa EJ, Stinnett AM, Blackwell TS, Prince LS. Interactions between NFkappaB and SP3 connect inflammatory signaling with reduced FGF-10 expression. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:15318–15325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.447318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]