Abstract

Objective

To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate effects of lifestyle intervention participation on weight reduction among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness.

Method

We systematically searched electronic databases for randomized controlled trials comparing lifestyle interventions with other interventions or usual care controls in overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness, including schizophrenia spectrum or mood disorders. Included studies reported change in weight [kg] or body mass index (BMI) [kg/m2] from baseline to follow-up. Standardized mean differences (SMD) were calculated for change in weight from baseline between intervention and control groups.

Results

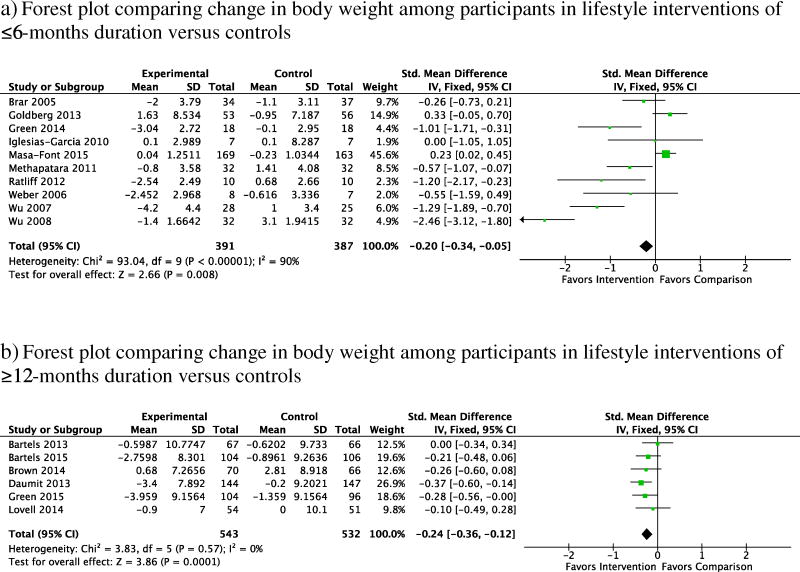

Seventeen studies met inclusion criteria (1968 participants; 50% male; 66% schizophrenia spectrum disorders). Studies were grouped by intervention duration (≤ 6-months or ≥ 12-months). Lifestyle interventions of ≤ 6-months duration showed greater weight reduction compared with controls as indicated by effect size for weight change from baseline (SMD = − 0.20; 95% CI = − 0.34, − 0.05; 10 studies), but high statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 90%). Lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration also showed greater weight reduction compared with controls (SMD = − 0.24; 95% CI = − 0.36, − 0.12; 6 studies) with low statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

Conclusion

Lifestyle interventions appear effective for treating overweight and obesity among people with serious mental illness. Interventions of ≥ 12-months duration compared to ≤ 6-months duration appear to achieve more consistent outcomes, though effect sizes are similar for both shorter and longer duration interventions.

Keywords: Mental illness, Schizophrenia, Bipolar disorder, Obesity, Weight loss, Lifestyle intervention

1. Introduction

Obesity among people with serious mental illness is a major public health concern. Rates of obesity in this at-risk group consisting of people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder, are nearly double observed rates in the general population [1–3]. Obesity combined with high chronic disease burden, increased cardiovascular risk, and poor health behaviors, contributes to dramatically reduced life expectancy among people with serious mental illness [4–6]. Numerous challenges interfere with achieving weight loss among overweight and obese individuals with serious mental illness including metabolic effects of psychoactive medications, impact of symptoms on motivation, poor dietary habits, and high levels of sedentary behavior [2,7,8]. Chronic poverty also places individuals with serious mental illness at increased risk of homelessness, and has devastating consequences on quality of life, self-esteem and ability to pursue leisure activities such as engaging in exercise [9].

Weight reduction among overweight and obese individuals is an important target for improving cardiovascular health. Research shows that even modest weight loss of 5–10% can reduce cholesterol levels, improve glycemic control, and lower blood pressure [10–12]. Extensive research supports lifestyle interventions focused on nutrition education and increasing physical activity participation for achieving weight loss in general patient populations [13–15]. However, among people with serious mental illness, evidence to support lifestyle interventions remains mixed [16]. This can partly be attributed to methodological limitations with many of the intervention studies conducted to date. For example, over the past decade there has been growing interest in supporting weight loss and cardiovascular risk reduction among people with serious mental illness through lifestyle interventions, however many studies have lacked adequate comparison conditions, have recruited small sample sizes, and have collected outcomes after short follow-up periods [16].

Despite these concerns, prior systematic reviews have highlighted the acceptability of lifestyle interventions for promoting physical activity and healthy eating among people with serious mental illness [17,18], and meta-analyses have demonstrated potential effectiveness of lifestyle interventions of short duration (≤ 6 months) for achieving weight loss in this high-risk group [19–21]. However, there are significant limitations related to these prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses. First, many reviews have included studies that enrolled participants who were not overweight or obese defined as having a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2; therefore, it is difficult to determine true effectiveness of lifestyle interventions specifically for achieving weight loss among overweight and obese individuals with serious mental illness. Second, existing meta-analyses have not been restricted to randomized studies, thereby making it difficult to reliably draw conclusions regarding the effect of lifestyle interventions compared to control conditions. Third, there has been a recent emergence of several large-scale rigorous trials of longer duration (≥ 12 months) lifestyle interventions for weight loss since many of the existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses were published. Therefore, an updated analysis of the effect of lifestyle interventions for weight loss among people with serious mental illness is warranted.

We conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized trials of lifestyle interventions targeting weight loss among people with serious mental illness. Specifically, our aim was to estimate the effect of lifestyle intervention participation on reduction in body weight among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness. We assessed the effects of lifestyle interventions promoting physical activity and healthy eating of short (≤ 6 months) and long (≥ 12 months) duration on change in participants’ body weight. The effect of lifestyle interventions was also assessed with respect to obtaining clinically significant weight reduction for participants as indicated by a weight loss of 5% or greater among studies of lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data sources and search strategy

We adhered to the PRISMA reporting guidelines [22]. The search strategy protocol was published to the PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews (Registration number: CRD42015019026). The following databases were searched in May 2016 for randomized controlled trials evaluating lifestyle interventions for weight loss in overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness: Medline, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Central, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. Reference lists of included studies, prior systematic reviews, and Google Scholar were also searched to identify additional relevant studies. The search strategy included a combination of key words and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms related to “serious mental illness”, “weight loss”, and “lifestyle intervention”. Table 1 lists the complete search strategy used in Medline.

Table 1.

Search strategy for Medline.

| Search | Search terms |

|---|---|

| #1 | “Schizophrenia”[Mesh] OR “Schizophrenia and Disorders with Psychotic Features”[Mesh] OR “Bipolar Disorder”[Mesh] OR “Psychotic Disorders”[Mesh] OR “Mood Disorders” [Mesh] OR “Depressive Disorder” [Mesh] OR “Antipsychotic Agents” [Mesh] OR “Psychotropic Drugs” [Mesh] |

| #2 | Schizophrenia OR “Psychotic Disorder*” OR Psychosis OR “Bipolar Disorder” OR “Mood Disorder*” OR Bipolar OR Schizoaffective OR “Severe Mental Illness” OR “Serious Mental Illness” OR “Major Depressive Disorder” OR “Depressive Disorder” OR “Antipsychotic*” OR “Psychotropic*” OR “Psychoactive*” |

| #3 | #1 OR #2 |

| #4 | “Obesity” [Mesh] OR “Body Weight” [Mesh] OR “Weight Loss” [Mesh] OR “Weight Gain” [Mesh] OR “Body Weight Changes” [Mesh] |

| #5 | “Obesity” OR “Overweight” OR “Body Weight” OR “Weight Loss” OR “Weight Gain” OR “Weight Change” OR “Body Weight Changes” |

| #6 | #4 OR #5 |

| #7 | “Lifestyle”[Mesh] OR “Diet”[Mesh] OR “Exercise”[Mesh] OR “Health Behavior”[Mesh] OR “Health Promotion”[Mesh] OR “Weight Reduction Programs” [Mesh] OR “Nutritional Sciences” [Mesh] OR “Program Evaluation” [Mesh] OR “Intervention Studies” [Mesh] OR “Education” [Mesh] |

| #8 | “Lifestyle” OR “Diet” OR “Nutrition” OR “Exercise” OR “Physical Activity” OR “Health Behavior” OR “Health Promotion” OR “Weight Reduction Program” OR “Trial” OR “Intervention” OR “Program” OR “Management” OR “Education” |

| #9 | #7 OR #8 |

| #10 | #6 AND #9 |

| #11 (final search) | #3 AND #10 |

2.2. Inclusion criteria

In accordance with the PRISMA statement, we used the participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS) criteria [22] to assess study eligibility:

Participants

Adults (aged ≥ 18 years, no upper limit) classified as overweight or obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 25 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 for Asian populations) with serious mental illness defined as having either a schizophrenia spectrum (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder) or mood disorder (major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder).

Interventions

Any lifestyle intervention for weight loss. These included behavioral interventions and interventions targeting self-monitoring, dietary changes, nutrition education, fitness, exercise or physical activity. Interventions involving pharmacological agents, nutritional supplements, or surgical procedures were excluded.

Comparators

All types of comparison conditions were considered eligible. This included other lifestyle interventions, minimal interventions, or usual care.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was change in body weight at follow-up. This could be measured as change in weight (kg) or change in BMI (kg/m2) at follow-up. Eligible studies had to report a quantitative measure of change in body weight. We also included studies that reported the proportion of participants who achieved ≥ 5% weight loss at follow-up. This outcome was also collected because modest ≥ 5% weight loss is associated with reduction in cardiovascular risk among overweight and obese individuals [10,15,23].

Study design

Randomized controlled trials reporting weight outcomes at follow-up. No restrictions based on date of publication or language.

2.3. Study selection

One researcher (JAN) screened titles for relevant studies. Two researchers (JAN & KLW) independently screened abstracts of relevant studies for eligibility. The same two researchers compared lists of potentially eligible studies and decided on a final list of studies to undergo full-text review. The researchers resolved discrepancies regarding study inclusion/exclusion through discussion.

2.4. Data extraction

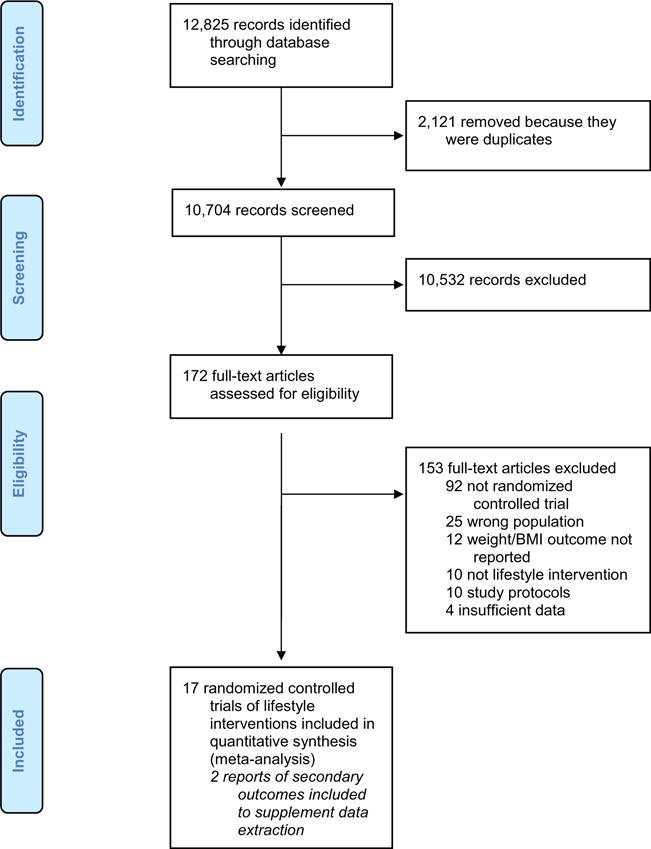

One researcher (JAN) extracted the following data from the full text articles using a data extraction form adapted from Avenell et al. [24]: study setting; participant characteristics (age, sex, and diagnosis); lifestyle intervention characteristics; comparison group characteristics; length of follow-up; and change in weight or BMI outcomes. A second researcher (KLW) reviewed the data tables to confirm accuracy of data extraction. Study inclusion and selection are illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). Results from a single study are often published as multiple manuscripts, such as reporting of secondary outcomes. Therefore, we were careful to avoid over counting studies, though secondary analyses from studies that met our inclusion criteria were also reviewed to supplement data extraction. All authors reviewed the final list of included studies.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of studies included in the review.

2.5. Methodological quality assessment

We used an adapted version of the Methodological Quality Rating Scale (MQRS) to assess methodological quality of included studies [25]. An item related to assessment of the control condition was included from another methodological quality assessment measure [26]. The adapted MQRS involves ratings for the following 12 methodological quality dimensions: 1) study design; 2) replicability of study procedures; 3) reporting of baseline characteristics; 4) use of manualized interventions; 5) adequate description of the comparison condition; 6) length of follow-up; 7) rate of follow-up; 8) objective outcome measurement; 9) study dropouts enumerated; 10) assessments completed by a person who is blind to participants’ treatment condition; 11) statistical analyses account for all participants as randomized; and 12) parallel replication at two or more sites. Total scores range from 0 (low) to 16 (high), where higher scores indicate greater quality. A score of 14 or higher is considered high quality. This assessment tool has been used in previous systematic reviews of interventions for people with serious mental illness [27–29]. One researcher (JAN) used the MQRS to assess quality of included studies. A second researcher (KLW) double-checked the quality rating scores for included studies. Both researchers then reviewed quality ratings and resolved any disagreements through discussion and consensus.

2.6. Publication bias

We used a funnel plot to test whether included studies were affected by publication bias and potential bias in outcome reporting. A funnel plot is a simple scatter plot of the intervention effect estimates from individual studies plotted on the horizontal axis, against the standard error of the estimated effect on the vertical axis [30]. We examined the funnel plot for asymmetry. In the absence of publication bias, the funnel plot should resemble a symmetrical funnel [30]. However, in the presence of bias, an asymmetrical appearance to the funnel will emerge because small studies without statistically significant effects were potentially unpublished. Greater asymmetry suggests greater bias. Publication bias is a concern in meta-analyses because it may lead to overestimation of the treatment effect of the intervention [30]. A sufficient number of studies (> 10) were identified to allow use of formal statistical tests for detecting funnel plot asymmetry [30]. The Egger test was used to perform a linear regression of the intervention effect estimates on their standard errors, where a significant test (p < 0.05) suggests funnel plot asymmetry [31]. The Begg-Mazumbar rank correlation test was also employed to assess the interdependence between effect estimates and their variances to identify funnel plot asymmetry [32]. Data on study effect estimates and standard errors were exported from RevMan 5.2 to Stata version 14.0 to conduct all statistical tests.

2.7. Meta analysis

We pooled randomized studies to compare standard mean differences in treatment effects between intervention and control conditions. Across all included studies, mean change in weight or BMI from baseline to follow-up was extracted. All weight values were converted to kilograms (kg) and BMI was assessed as weight (kg)/height (m)2. If studies reported different values for change in weight, such as completer only versus baseline observation carried forward, the more conservative estimate was used when possible.

The standard deviations for the mean change in the primary outcome (i.e., change in weight or change in BMI) were necessary to calculate the effect size for each study and to calculate the pooled effect estimate across studies. Most studies reported mean change in weight or mean change in BMI from baseline to follow-up with associated standard deviations. Otherwise, reported confidence intervals, standard errors, t values, p values or F values for the change in weight or BMI from baseline to follow-up were used to derive the standard deviation of the change. In one case there was insufficient information to calculate standard deviations for change in weight or BMI, and therefore standard deviations were imputed by employing a technique described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Section 16.1.3.2) [30] and by Follmann et al. [33]. In this approach we calculated a correlation coefficient using data from one study with sufficient detail reported [34]. The correlation coefficient describes how similar the baseline and final measurements are across participants.

Separate correlation coefficients were calculated for both the experimental and comparison groups using the following formula:

Because similar correlation coefficients were obtained for the experimental (Corr = 0.93) and the comparison (Corr = 0.95) groups, an average correlation coefficient (Corr = 0.94) was computed. Next, we used the correlation coefficient to impute standard deviations for the change from baseline for the experimental and comparison groups using the following formula:

In this method, the assumption is made that the correlation of within-participant pre-intervention and post-intervention weights were similar across studies. This assumption is appropriate given that the outcome measure (change in weight or BMI) was consistent across included studies.

Pooled results were presented as standard mean differences (SMD) in change in body weight with 95% confidence intervals from baseline to follow-up (pre-intervention vs. post-intervention) between intervention and comparison groups because weight (kg) and BMI (kg/m2) are continuous outcome measures. We used the Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager software (RevMan 5.2) to conduct meta-analyses using the inverse variance method and fixed effects models. The fixed effects model assigns more weight to studies that carry more information; therefore, studies with larger sample sizes had greater weight than studies with smaller sample sizes. Separate analyses were conducted for studies of lifestyle interventions of ≤ 6-months duration and of ≥ 12-months duration. We generated forest plots to present pooled results for the effect sizes of weight change from baseline between the lifestyle intervention and comparison conditions reflected as standardized mean differences (SMD) with associated 95% confidence intervals. The SMD provides a summary statistic for the size of the intervention effect in each study, and can be interpreted as the effect size described as Hedges’ g in the social sciences (see Section 9.2.3.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions) [30]. The SMD is also known as Cohen’s d, where the magnitude of the SMD can be interpreted as small (SMD = 0.2), medium (SMD = 0.5), or large (SMD = 0.8) [35,36]. A separate forest plot was created to illustrate the odds ratio and associated 95% confidence intervals for clinically significant weight loss of ≥ 5% between the lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration and comparison conditions. Z-scores were used to provide a test of overall effect. The I-square statistic was calculated to provide a measure of statistical heterogeneity between studies (> 25% was considered moderate heterogeneity; and > 50% was considered substantial heterogeneity).

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics

Study flow and reasons for exclusion are illustrated in Fig. 1. Over 10,000 references were screened after removal of duplicates, of which 172 full text articles were reviewed to determine eligibility. In total, 17 randomized controlled trials of lifestyle interventions for weight loss among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness met the inclusion criteria and could be included in statistical analyses of effect. Most included studies were from the United States (n = 11), and remaining studies were from Spain (n = 2), China (n = 1), Taiwan (n = 1), Thailand (n = 1), and the United Kingdom (n = 1). The studies recruited 1968 overweight or obese individuals with serious mental illness, of which 50% were male. Study participants primarily had schizophrenia spectrum disorders (66%) or bipolar disorder (22%). Additional study characteristics are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies of lifestyle interventions of ≤ 6-months and ≥ 12-months duration for weight loss among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness.

| Study, year, country | Sample size (N) | Diagnoses and age (M ± SD)a | Gender (% male) | Setting | Outcomes for meta-analysis | Lifestyle intervention | Comparison condition | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle interventions of ≤ 6-months duration | ||||||||

| Brar et al. 2005, United States [45] | 72 | Schizophrenia (54%); schizoaffective disorder (46%); age = 40.3–± 10.4 years | 40% | Outpatients or stable inpatients from 19 sites | Change in weight and BMI at 14-weeks | 14-Week Behavioral Treatment intervention consists of 20 group-based therapy sessions including 2 sessions per week for 6 weeks followed by 1 session per week for 8 weeks. Participants are taught techniques for self-monitoring food intake, changing eating habits, preventing overeating, and exercising more. | Participants were encouraged to lose weight on their own with no additional instructions. Monthly weight measurement. | Behavioral Treatment intervention participants lost more weight (mean = −2.–0 kg; S-D = 3.79) compared to the control group (mean = −1.1–0 kg; S-D = 3.11); the difference between groups was not significant. |

| Goldberg et al. 2013, United States [48] | 109 | Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (37%); bipolar disorder (25%); major depressive disorder (14%); posttraumatic stress or anxiety disorder (25%); age = 52.0–± 9.1 years | 81% | Outpatient mental health clinics in two VA Hospital Systems | Change in weight at 6-months | 6-Month MOVE! program includes individual and group sessions tailored to individuals with serious mental illness focused on motivation and engagement, education on basics of healthy eating and meal planning, and goal setting for weight loss and physical activity. | Standard services with additional monthly weigh ins and brochures and handouts about diet and exercise. | MOVE! program participants did not lose more weight (mean = 1.6 kg; S-D = 8.53) compared to the control group (mean = −0.9–5 kg; S-D = 7.19); the (continued on next page) difference between groups was not significant. |

| Green et al. 2014, United States [51] | 36 | All participants taking antipsychotic medications; age = 48.5–± 13.3 years | 19% | Integrated health plan | Change in weight at 12-weeks | 12-Week adapted version of the PREMIER intervention and DASH diet. Includes weekly 2-hour group sessions with emphasis on healthy eating, reducing sodium intake, decreasing portion sizes, increasing moderate exercise, and daily use of a food diary. | Usual care only. | 12-Week lifestyle intervention participants lost significantly more weight (mean = −3.0–4 kg; S-D = 2.72) compared to the control group (mean = −0.–1 kg; S-D = 2.95) (p = 0.00–4). |

| Iglesias-García et al. 2010, Spain [40] | 14 | Schizophrenia (100%); age = 39.9–± 11.3 years | 69% | Single community mental health center | Change in weight and BMI at 12-weeks | 12-Week program consisting of 12 group sessions led by a psychiatric nurse covering information and counseling about nutrition, exercise, healthy habits, and self-esteem. | Control condition with weekly visits to the clinic for anthropometric measurement. | No difference in weight loss between the intervention (mean = 0.1 kg; S-D = 2.99) and control (mean = 0.1 kg; S-D = 8.29) groups. |

| Masa-Font et al. 2015, Spain [42] | 332 | Schizophrenia (67%); schizoaffective disorder (17%); bipolar disorder (16%); age = 46.7–± 9.4 years | 55% | Ten public mental health teams | Change in BMI at 3-months | 24 Group physical activity sessions (twice weekly) including instruction and pedometers. 16 group dietary sessions (twice weekly) with healthy eating education and food diary. | Usual care consisting of regular treatment and check-ups with psychiatrist. | Weight loss was (continued on next page) greater in the control group (mean = −0.2–3 kg; S-D = 1.03) compared to the intervention group (mean = 0.04-kg; S-D = 1.25) (p = 0.03–8). |

| Methapatara & Srisurapanont 2011, Thailand [46] | 64 | Schizophrenia (100%); age = 40.4–± 10.1 years | 64% | Outpatients from psychiatric hospital | Change in weight and BMI at 12-weeks | Intervention consists of using a pedometer and 5 group sessions with motivational interviewing to get more physical activity, nutrition education, and setting daily step goals. | Usual care and a paper leaflet about healthy lifestyle. | Intervention participants lost significantly more weight (mean = −0.–8 kg; S-D = 3.58) compared to the control group (mean = 1.41-kg; S-D = 4.08) (p = 0.03- |

| Ratliff et al. 2012, United States [43] | 10 | Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (60%); other serious mental illness (40%); age = 49.0–± 8.1 years | 30% | Community mental health center | Change in weight and BMI at 8-weeks weekly group sessions focused on nutrition education, changing attitudes to support weight loss, choosing healthy food options, reducing calorie intake, and increasing daily physical activity. Financial reimbursement up to $20 per week for purchasing items from a healthy food list. | 8-Week SIMPLE (Simplified Intervention to Modify Physical Activity, Lifestyle, and Eating) program consisting of | Waitlist control group. | Participants in the SIMPLE program lost significantly more weight (mean = −2.5–4 kg; S-D = 2.49) compared to the control group (mean = 0.68-kg; S-D = 2.66) (p = 0.02−). |

| Weber & Wyne 2006, United States [44] | 17 | Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (100%); age = NR | 29% | Urban public mental health clinic | Change in weight and BMI at 16-weeks | 16-Week group cognitive/behavioral program adapted from the Diabetes Prevention Program. Includes goal setting, problem solving, nutrition education, increasing physical activity, and daily food and activity tracking using a diary. | Treatment as usual with regular weight measurement. | Intervention participants lost more weight (mean = −2.4–5 kg; S-D = 2.97) compared to the control group (mean = −0.6–2 kg; S-D = 3.34); the difference between groups was not significant. |

| Wu et al. 2007, Taiwan [50] | 53 | Schizophrenia (100%); age = 40.7–± 7.1 years | 42% | Veterans hospital inpatient unit | Change in weight and BMI at 6-months | 6-Month weight management program consisting of dietary control led by a registered dietitian focused on reducing caloric intake combined with supervised physical activity three days per week. | Control group. | Participants in the weight management program lost significantly more weight (mean = −4.–2 kg; SD = 4.4) compared to the control group (mean = 1.0 kg; SD = 3.4) (p < 0.0–01). |

| Wu et al. 2008, China [47] | 64 | Schizophrenia (100%); age = 26.1–± 4.9 years | 52% | Outpatient mental health clinic at an academic medical center | Change in weight and BMI at 12-weeks | 12-Week lifestyle intervention combining psychoeducational, dietary, and exercise components. Includes nutrition education, healthful weight management techniques, dietary intervention and caloric reduction, supervised exercise sessions, home-based exercises, and daily food and exercise diary. Participants were also instructed to take a placebo daily and to maintain a record sheet. | Instruction to take a placebo daily and to maintain a record sheet. | Lifestyle intervention participants lost significantly more weight (mean = −1.–4 kg; S-D = 1.66) compared to the control group (mean = 3.1 kg; S-D = 1.94) (p < 0.0–01). |

| Lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration | ||||||||

| Bartels et al. 2013, United States [37] | 133 | Schizophrenia (18%); schizoaffective disorder (13%); bipolar disorder (35%); major depression (34%); age = 43.8–± 11.5 years | 38% | Single community mental health center | Change in weight and BMI at 12-months; ≥ 5% weight loss at 12-months | 12-Month In SHAPE program consists of weekly individual sessions with a fitness trainer, fitness club membership, and nutrition education. | Fitness club membership and an introduction to safe use of exercise equipment. | There was no difference in weight loss between participants in the In SHAPE program (mean = −0.6–0 kg; S-D = 10.7–8) and the comparison group (mean = −0.6–2 kg; S-D = 9.73). |

| Bartels et al. 2015, United States [34] | 210 | Schizophrenia (23%); schizoaffective disorder (32%); bipolar disorder (29%); major depression (16%); age = 43.9– ± 11.2 years | 49% | Three urban community mental health centers | Change in weight and BMI at 12-months; ≥ 5% weight loss at 12-months | 12-Month In SHAPE program consists of weekly individual sessions with a fitness trainer, fitness club membership, and nutrition education. | Fitness club membership and an introduction to safe use of exercise equipment. | Participants in the In SHAPE program lost more weight (mean = −2.7–6 kg; S-D = 8.30) compared to the control group (mean = −0.9–0 kg; S-D = 9.26); the difference between groups was not significant. |

| Brown et al. 2014, United States [38] | 136 | Schizophrenia (100%); age = 44.6–± 11.0 years | 33% | Four urban and suburban community mental health centers | Change in weight at 12-months | 12-Month RENEW program combines weight-loss and psychiatric rehabilitation strategies and includes: 3-month intensive phase with weekly group nutrition and exercise sessions; 3-month maintenance phase with monthly group sessions, weekly exercise classes, weekly phone support, and weekly reminders and tips; and 6-month intermittent support phase with weekly phone calls and monthly newsletters with tips, reminders, and encouragement. | Treatment as usual consisting of medication and case management and the opportunity to participate in wellness programming offered at the study sites. | Participants in the RENEW program did not lose more weight (mean = 0.68-kg; S-D = 7.27) compared to the control group (mean = 2.81-kg; S-D = 8.92). |

| Daumit et al. 2013, United States [39] | 291 | Schizophrenia (29%); schizoaffective disorder (29%); bipolar disorder (22%); major depressive disorder (12%); other (8%); age = 45.3–± 11.3 years | 50% | Community psychiatric rehabilitation programs | Change in weight and BMI at 18-months; ≥ 5% weight loss at 12-months | 18-Month ACHIEVE program focused on self-monitoring, reducing caloric intake, healthy eating, and participating in moderate exercise. Program includes group weight-management sessions, individual weight-management sessions, and group exercise sessions. | Standard nutrition and physical activity information and quarterly health classes with content unrelated to weight loss. | ACHIEVE participants lost significantly more weight (mean = −3.–4 kg; S-D = 7.89) compared to the control group (mean = −0.–2 kg; S-D = 9.20) (p = 0.00–2). |

| Erickson et al. 2016, United States [49] | 122 | Schizophrenia (45%); schizoaffective disorder (19%); bipolar disorder (30%); other (6%); age = 49.6–± 8.0 years | 89% | Psychiatric clinics in an urban VA Hospital System | ≥ 5% weight loss at 12-months | Adapted version of the evidence-based Diabetes Prevention Program Lifestyle Balance Program. Consists of 8 weekly group nutrition education classes, dietary monitoring, individualized goal setting, and optional group exercise sessions. Individualized goal setting meetings continue monthly for 12-months. | Usual care consists of encouragement to exercise and eat healthy, and printed self-help materials about weight loss, exercise, and nutrition. | More participants in the intervention group (33%) compared to the control group (19%) achieved ≥ 5% weight loss; the difference between groups was not significant. |

| Green et al. 2015, United States [52] | 200 | Schizophrenia spectrum disorder (29%); bipolar disorder or affective psychosis (69%); posttraumatic stress disorder (2%); age = 47.2–± 10.6 years | 28% | Community mental health centers and a not-for-profit integrated health system | Change in weight and BMI at 12-months; ≥ 5% weight loss at 12-months | 12-Month STRIDE program based on the PREMIER lifestyle intervention and DASH diet. 6-months of weekly group meetings covering nutrition, lifestyle changes, and physical activity. 6-months maintenance phase with monthly group sessions and monthly individual telephone sessions. | Usual care only. | STRIDE participants lost significantly more weight (mean = −3.9–6 kg; 9.16) compared to the control group (mean = −1.3–6 kg; S-D = 9.16) (p < 0.0–5). |

| Lovell et al. 2014, United Kingdom [41] | 105 | Schizophrenia spectrum disorder (85%); other psychosis (15%); age = 25.7–± 5.7 years | 60% | Two early intervention services | Change in weight and BMI at 12-months | Healthy living intervention combines motivational and behavioral components to facilitate exercise and dietary change. Includes 7 individual sessions with a trained support/recovery worker over 6 months, and a booster session at 9–10 months. Access to optional group nutrition and physical activity classes, and available booklet and website with educational information and healthy recipes. | Treatment as usual includes: enhanced care coordination, specific care plan, access to early intervention services, and support from case managers to undertake physical health activities. No formal weight control activities. | Intervention participants lost more weight (mean = −0.–9 kg; SD = 7.0) compared to the control group (mean = 0 kg; S-D = 10.1); the difference between groups was not significant. |

BMI: body mass index (kg/m2). M ± SD: mean (standard deviation). NR: not reported.

Calculation of the mean age for the total sample involved combining means and standard deviations when the intervention and control groups were reported separately using the following formula to obtain the mean [(m1 * n1 + m2 * n2) / (n1 + n2)] and corresponding standard deviation [((SD12 * n1 + SD2 * n2) / (n1 + n2))0.5]. When 95% Confidence Intervals were reported, the following formula was used to convert the confidence intervals to standard deviations [(n0.5) * ((upper limit − lower limit) / 3.92)]. These calculations are outlined in section 7.7.3. of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [30].

3.2. Lifestyle intervention characteristics

The lifestyle interventions primarily included standard nutrition education combined with instruction and encouragement to increase regular participation in physical activity. The programs were delivered through community mental health centers [34,37–44], outpatient services at psychiatric hospitals [45–47], inpatient units or outpatient clinics at veterans’ hospitals [48–50], or within an integrated health plan [51,52]. Several interventions were adapted from existing evidence-based programs developed and evaluated for use in general patient populations such as the Diabetes Prevention Program [44,49] and the DASH Diet [51,52]. Several studies described efforts to tailor evidence-based nutrition education information and physical activity guidelines to specifically meet the needs and cognitive abilities of people with serious mental illness. This involved simplifying the lessons plans, applying guiding social cognitive and behavioral theories, combining psychiatric rehabilitation and skill building content, integrating materials related to mental health symptoms and how these symptoms can interfere with healthy eating and getting exercise, consideration of the effects of psychiatric medications on weight, and incorporating different strategies to encourage and motivate participants [34,37–39,41,43,48,52]. Many interventions were group-based [38,40,42–46,49,51], combined group and individual sessions [39,41,48,52], or were individually focused [34,37,47,50]. A range of different providers delivered the lifestyle interventions including fitness trainers or health coaches with specialized training for working with individuals with serious mental illness [34,37], other providers with basic training for working with people with mental illness [45], trained members of the study staff [39,46–48], mental health counselors [52], trained recovery workers [41], dietitians [47,50], psychiatric nurses [40,42,44], or an exercise physiologist [47].

3.3. Control condition characteristics

As illustrated in Table 2, several different types of control conditions were used. Most studies compared lifestyle interventions to usual care, which generally consisted of medication and case management [38,41,42,50–52]. Participants in the comparison groups in other studies received usual care with the addition of regular weight measurement [40,44,45], paper handouts with basic information about healthy lifestyle [46], self-help materials with basic nutrition information and encouragement to increase physical activity participation [49], monthly weight measurement combined with handouts about diet and exercise [48], and a placebo [47]. In one study the comparison group participants were enrolled in a waitlist group [43]. In another study, the comparison group received standard nutrition and physical activity information combined with quarterly health classes with content not focused on weight loss [39]. Two studies used an active comparison group consisting of access to a fitness club membership at a local community facility [34,37].

3.4. Methodological quality assessment

Quality assessment scores for the included studies are listed in Table 3. The quality scores for included studies were generally high, given that all studies employed randomized controlled designs, evaluated lifestyle interventions with manuals or defined procedures, collected objective weight loss outcomes, and reported sufficient details to enable replication. There were also several quality metrics that were not met by many of the studies. These included follow-up length of 12-months or greater [40,42–48,50,51], follow-up rate of at least 85% [34,37,38,45,48–50], use of blinded outcome assessment [38,43,46,48], and recruitment through multiple study sites [37,40,43,44,46,47,50,51].

Table 3.

Methodological quality ratings of the included randomized controlled trials of lifestyle interventions for weight loss among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness.

| MQRS dimensions Study |

1 Study Designa |

2 Sufficient detail to enable replicationb |

3 Baseline characteristics reportedc |

4 Lifestyle intervention has standardized manual and proceduresd |

5 Control condition adequately describede |

6 Follow-up lengthf |

7 Follow- up rateg |

8 Objective outcome measures reportedh |

9 Dropouts are enumeratedi |

10 Assessments completed by person blind to participants' treatment conditionj |

11 Analyses include all participants as randomizedk |

12 Multiple sitesl |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle interventions of ≤ 6-months duration | |||||||||||||

| Brar et al. 2005, United States [45] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Encouraged to lose weight (1) | 14 weeks (0) | 69% (0) | Weight & BMI (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | 12 |

| Goldberg et al. 2013, United States [48] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Standard services and handouts (1) | 6 months (0) | 65% (0) | Weight (1) | No (0) | No (0) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | 10 |

| Green et al. 2014, United States [51] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | No (0) | Yes (1) | Usual care (0) | 12 weeks (0) | 97% (2) | Weight (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | No (0) | 11 |

| Iglesias-García et al. 2010, Spain [40] | RCT (3) | No (0) | No (0) | No (0) | Weekly clinic visits (1) | 12 weeks (0) | 93% (2) | Weight &BMI (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | No (0) | No (0) | 9 |

| Masa-Font et al. 2015, Spain [42] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Usual care (1) | 3 months (0) | 86% (2) | BMI (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | 14 |

| Methapatara & Srisurapanont 2011, Thailand [46] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Usual care and leaflet (1) | 12 weeks (0) | 100% (2) | Weight & BMI (1) | Yes (1) | No (0) | Yes (1) | No (0) | 12 |

| Ratliff et al. 2012, United States [43] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | No (0) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | 8 weeks (0) | 90% (2) | Weight & BMI (1) | Yes (1) | No (0) | No (0) | No (0) | 10 |

| Weber & Wyne 2006, United States [44] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | No (0) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | 16 weeks (0) | 88% (2) | Weight & BMI (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | No (0) | No (0) | 11 |

| Wu et al. 2007, Taiwan [50] | RCT (3) | No (0) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | No (0) | 6 months (1) | NR (0) | Weight & BMI (1) | No (0) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | No (0) | 9 |

| Wu et al. 2008, China [47] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | 12 weeks (0) | 91% (2) | Weight & BMI (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | No (0) | 13 |

| Lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration | |||||||||||||

| Bartels et al. 2013, United States [37] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Fitness club membership (1) | 12 months (2) | 78% (1) | Weight & BMI (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | No (0) | 14 |

| Bartels et al. 2015, United States [34] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Fitness club membership (1) | 12 months (2) | 84% (1) | Weight & BMI (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | 15 |

| Brown et al., 2014, United States [38] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Treatment as usual (1) | 12 months (2) | 68% (0) | Weight (1) | No (0) | No (0) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | 12 |

| Daumit et al. 2013, United States [39] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Standard nutrition and physical activity information (1) | 18 months (2) | 96% (2) | Weight & BMI (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | 16 |

| Erickson et al. 2016, United States [49] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Usual care and printed self-help materials (1) | 12 months (2) | 51% (0) | ≥ 5% weight loss (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | No (0) | Yes (1) | 13 |

| Green et al. 2015, United States [50] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Usual care (0) | 12 months (2) | 85% (2) | Weight & BMI (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | 15 |

| Lovell et al. 2014, United Kingdom [41] | RCT (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Treatment as usual (1) | 12 months (2) | 89% (2) | Weight & BMI (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | 16 |

MQRS: Methodological Quality Rating Scale. BMI: body mass index (kg/m2). RCT: randomized controlled trial. NR: not reported.

Scores: 0 = no posttest; 1 = single group pretest-posttest; 2 = quasi-experimental (non-equivalent control group); 3 = randomized controlled trial.

Scores: 0 = insufficient detail about the intervention and follow-up; 1 = sufficient detail about the procedures provided to enable replication.

Scores: 0 = no baseline characteristics reported; 1 = baseline characteristics reported.

Scores: 0 = no standardized intervention procedures; 1 = standardized intervention procedures or manual.

Scores: 0 = no description of control group; 1 = control group is adequately described and includes treatment as usual or other established or credible treatment.

Scores: 0 = less than 6 months; 1 = 6–11 months; 2 = 12 months or greater.

Scores: 0 = less than 70% completion; 1 = 70–84.9% completion; 2 = 85–100% completion.

Scores: 0 = no objective outcomes reported; 1 = objective outcomes reported.

Scores: 0 = no enumeration of dropouts; 1 = enumeration of dropouts.

Scores: 0 = follow-up conducted by non-blind or unspecified method; 1 = follow-up by person blind to participants’ treatment allocation.

Scores: 0 = statistical analyses were clearly inappropriate or not reported; 1 = statistical analyses include all participants as randomized (referred to as intention to treat analysis).

Scores: 0 = single study site; 1 = multiple study sites.

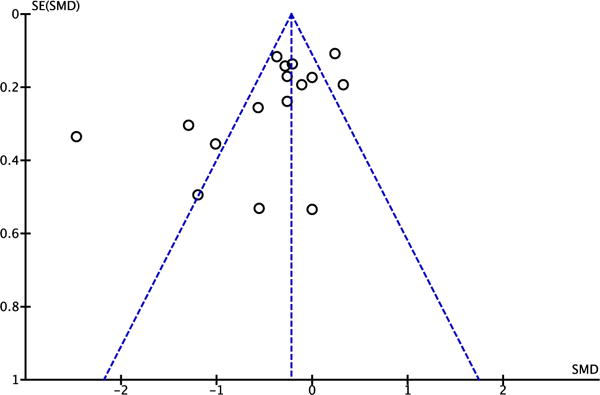

3.5. Publication bias

Studies of all durations were included in the assessment of funnel plot asymmetry to ensure a sufficient number of studies to conduct the statistical tests (Fig. 2). For the 16 studies reporting change in body weight as continuous outcome measures (change in weight [kg] or BMI [kg/m2]), the Egger test (bias = − 3.18; 95% CI − 5.97, −0.39; p = 0.029) indicated asymmetry in the funnel plot suggesting possible publication bias. However, this finding was not confirmed using the Begg-Mazumdar test (Kendall’s score = − 34; z = − 1.53; p = 0.126).

Fig. 2.

Funnel plot comparing the standardized mean difference (x-axis) against its standard error (y-axis) for all studies reporting change in body weight.

Most studies are within the pseudo 95% CI of the funnel plot, suggesting moderate to low risk of publication bias among studies reporting change in body weight as a continuous outcome measure (change in weight [kg] or BMI [kg/m2]). In statistical tests, the Egger test (bias = − 3.18; 95% CI − 5.97, − 0.39; p = 0.029) indicated asymmetry in the funnel plot, suggesting possible publication bias. Though this was not confirmed using the Begg-Mazumdar test (Kendall’s score = − 34; z = − 1.53; p = 0.126).

SMD: standard mean difference.

SE: standard error.

BMI: body mass index (kg/m2).

3.6. Meta-analysis

3.6.1. Change in weight in lifestyle interventions of ≤ 6-months duration

Fig. 3a illustrates pooled results as standard mean differences in change in body weight for studies of lifestyle interventions of ≤ 6-months duration (range: 8-weeks to 6-months). The ten studies favored lifestyle intervention participation compared to the controls (SMD = − 0.20; 95% CI = − 0.34, − 0.05). However, there was considerable statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 93.04; df = 9; p < 0.001; I2 = 90%).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots for the meta-analysis.

a) Forest plot comparing change in body weight among participants in lifestyle interventions of ≤ 6-months duration versus controls.

b) Forest plot comparing change in body weight among participants in lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration versus controls.

3.6.2. Change in weight in lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration

Fig. 3b illustrates pooled results as standard mean differences in change in body weight for studies of lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration (range: 12-months to 18-months). The six studies favored lifestyle intervention participation compared to the controls (SMD = − 0.24; 95% CI − 0.36, − 0.12). Importantly, statistical heterogeneity was very low and non-significant for change in weight (χ2 = 3.83; df = 5; p = 0.57; I2 = 0%).

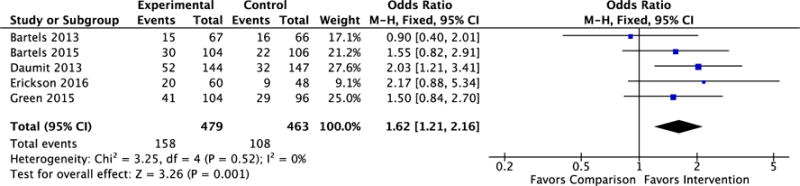

3.6.3. Clinically significant weight loss among lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration

Five studies of lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration reported clinically significant ≥ 5% weight loss at follow-up. Fig. 4 illustrates the pooled effect of these studies. The pooled results demonstrated that participants in interventions of ≥ 12-months duration showed significantly greater odds of achieving ≥ 5% weight loss compared to control participants at follow-up (OR, 1.62; 95% CI 1.21, 2.16; 5 studies). There was low statistical heterogeneity among studies reporting ≥ 5% weight loss (χ2 = 3.25; df = 4; p = 0.52; I2 = 0%).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the odds of achieving clinically significant (5% or greater) weight loss among participants in lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration versus controls.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we found that lifestyle interventions of both ≤ 6-months and ≥ 12-months duration led to modest but significant weight loss among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness when compared to control conditions. The ten studies of lifestyle interventions of ≤ 6-months duration showed significant heterogeneity, indicating high variance and that effect estimates from these studies should be interpreted cautiously [40,42–48,50,51]. However, the six studies of lifestyle interventions of ≥ 12-months duration that reported weight loss as a continuous outcome (the seventh study reported the proportion of participants who achieved clinically significant weight loss) showed very low statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) [34,37–39,41,52]. This indicates that there was negligible variance among these six studies of longer duration interventions and suggests that overall effect estimates for these studies are more reliable and consistent. It is most likely that the small sample sizes and shorter length of follow-up were the primary contributors to the greater heterogeneity observed among the studies of shorter duration interventions given that there were no major differences between studies of shorter duration compared to longer duration interventions due to individual participant characteristics or structure of the content of the intervention or control groups.

Our finding of significant weight reduction among the shorter duration (≤ 6-months) lifestyle interventions is consistent with prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses [19,20]. Importantly, we were able to expand on these prior reviews by including several recently published reports of large-scale trials of longer duration lifestyle interventions. As a result, our systematic review and meta-analysis is the first to our knowledge to highlight the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions of at least 12-month duration for achieving significant weight loss among overweight and obese individuals with serious mental illness. However, we found that both interventions of ≤ 6-months duration and ≥ 12-months duration contributed to a comparable effect on weight loss, as reflected by a standardized mean difference (SMD) for weight change from baseline of roughly 0.20. This is considered a small effect [35], which suggests that it may be difficult to draw conclusions regarding whether the longer duration interventions are more effective than the shorter duration interventions. Based on results reported in five studies, we found that participation in the longer duration lifestyle interventions contributed to over 60% greater odds of achieving clinically significant ≥ 5% weight loss when compared to control conditions.

We found that across the 17 studies included in this review, the lifestyle interventions had several different features such as group or individually focused sessions, or were delivered by a range of providers with varying levels of training and expertise. Given that the interventions used multiple combinations of different or overlapping components, it was not possible to isolate specifically which components were most effective for contributing to weight loss. However, there were also several important design elements that were consistent across the lifestyle interventions. For example, manuals or clearly defined procedures were available for delivering all the programs, and principles of psychiatric rehabilitation were frequently used to support evidence-based group or individually focused nutrition education and exercise instruction. The majority of studies (n = 15), including all seven studies of longer duration lifestyle interventions, were conducted through community or outpatient mental health settings. This is important given that people with serious mental illness receive the majority of their care through these types of settings [16].

The methodological quality of the included studies was high, but this is largely because we restricted our review to include only randomized controlled trials that evaluated lifestyle interventions with clear procedures for targeting either healthy eating or physical activity or both, and that reported clearly defined weight outcomes. This is in contrast to a prior systematic review that included studies of differing designs, such as single-group pre-post, uncontrolled feasibility, or quasi-experimental designs, where many studies were found to have low methodological quality [17]. As reflected in Fig. 2, there was possible publication bias as indicated by a significant Egger test, though this was not confirmed using the Begg-Mazumdar test. Therefore, risk of publication bias was low, which may further reflect the inclusion of only randomized controlled trials and the overall high methodological quality of included studies. Our findings also show that there has been progress towards addressing previously identified methodological limitations with the evidence related to lifestyle interventions for people with serious mental illness. For example, a prior literature review raised concerns about there being insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding effectiveness of lifestyle interventions for weight loss [53], while other reviews have emphasized the need for studies with larger sample sizes, longer follow-up, and reporting of clinically significant outcomes [17,18,20]. We found that most (n = 11) of the 17 included randomized controlled trials, and all 7 of the studies of longer duration lifestyle interventions, were published within the past five years (since 2012). Therefore, our findings reflect the increasing recognition of the need and prioritization of programs aimed at addressing elevated overweight and obesity rates among people with serious mental illness [2], and that these efforts have made substantial advances in recent years.

4.1. Limitations and future research

There are several limitations that warrant consideration. First, we were unable to determine whether weight loss was sustained over time among people with serious mental illness, and we found that among studies reporting long-term weight loss outcomes, the findings were mixed. For example, in one of the trials included in this review, significant weight loss persisted at 6-month follow up after completion of the active intervention [34]. However, a recent secondary report on long-term outcomes from another one of the trials included in this review indicated that the successful weight loss achieved during the active intervention phase diminished during the 12-months following completion of the intervention, though some clinically meaningful benefits persisted [54]. Efforts are needed to determine how to sustain weight loss following lifestyle intervention participation because long-term outcomes are critical for reducing cardiovascular risk. Second, participants’ mean age across most included studies exceeded 40 years, suggesting that our findings likely do not generalize to younger individuals with serious mental illness. This is a significant concern because young adults with serious mental illness are at risk of substantial weight gain as a result of mental illness onset and its consequences on functioning and motivation, and due to the initiation of antipsychotic treatment [55,56]. Few studies have reported on the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions for weight loss among over-weight and obese young adults with serious mental illness [57,58]. This highlights an important area of future research focused on early intervention to address health behaviors and risk factors that contribute to poor cardiovascular health later in life. Third, while weight and BMI are considered reliable measures of obesity, there are other important outcomes that require investigation. Many of the included studies reported secondary outcomes, such as fitness, lipid levels, or blood glucose; however, analyses of these outcomes was beyond the scope of this review and meta-analysis. Specifically, fitness may be an important target for lifestyle interventions given recent evidence demonstrating that individuals with serious mental illness may have greater motivation to achieve improved fitness as opposed to weight loss, and that improved fitness has other important benefits such as reduction in mental health symptoms such as depression and improved physical functioning [59–61]. Fourth, given the small number of studies that met our inclusion criteria, we cannot reliably assess what factors contributed to the greater heterogeneity observed among the shorter duration interventions compared to the longer duration interventions. The findings from this review and meta-analysis demonstrate the effectiveness of both short and long duration lifestyle interventions for achieving weight loss among individuals with serious mental illness, thereby providing support for the implementation of these programs in mental health settings. Lastly, it is not clear whether the lifestyle interventions evaluated in the studies included in this review were implemented or widely disseminated following completion of the respective trials. Importantly, we did not specifically assess the costs of delivering the different lifestyle interventions of both short and long duration. Future efforts are needed to better understand the costs of delivering lifestyle interventions for people with serious mental illness in order to inform the implementation and sustainability of these interventions within real-world mental health settings [16].

5. Conclusion

Our updated systematic review and meta-analysis provides further support for the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions for achieving weight loss among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness. Importantly, we identified several recent large-scale randomized controlled trials of lifestyle interventions of at least 12-months duration, which appeared to yield consistent and reliable weight loss outcomes. Our findings also show that over the past 5 years (since 2012) there have been substantial advances towards addressing the disproportionately elevated obesity rates among people with serious mental illness. Despite this progress, it is clear that continued efforts are needed to demonstrate sustained weight loss outcomes, reach more young people with serious mental illness, and implement evidence-based health promotion programming within mental health care settings. To date, there is limited evidence to support the long-term sustainability of lifestyle interventions for individuals with serious mental illness. Furthermore, ongoing efforts are needed to demonstrate that lifestyle interventions not only contribute to weight loss, but may contribute to improved cardiovascular health and reduced risk of early mortality among people with serious mental illness.

Footnotes

Disclosures and acknowledgements: No financial disclosures were reported by any of the authors of this manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

This study was supported by grants from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC U48DP001935) and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH078052 and R01 MH089811). Additional support was received from the Health Promotion Research Center at Dartmouth (Cooperative Agreement Number U48 DP005018). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. No financial disclosures were reported by any of the authors of this manuscript. The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Dickerson FB, Brown CH, Kreyenbuhl JA, Fang L, Goldberg RW, Wohlheiter K, et al. Obesity among individuals with serious mental illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(4):306–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison DB, Newcomer JW, Dunn AL, Blumenthal JA, Fabricatore AN, Daumit GL, et al. Obesity among those with mental disorders: a National Institute of Mental Health meeting report. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4):341–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daumit GL, Clark JM, Steinwachs DM, Graham CM, Lehman A, Ford DE. Prevalence and correlates of obesity in a community sample of individuals with severe and persistent mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191(12):799–805. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000100923.20188.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein S, Morrato EH, Marcus SC. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Med Care. 2011;49(6):599–604. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820bf86e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. 2015;72(4):334–41. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stubbs B, Williams J, Gaughran F, Craig T. How sedentary are people with psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2016;171(1–3):103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilbourne AM, Rofey DL, McCarthy JF, Post EP, Welsh D, Blow FC. Nutrition and exercise behavior among patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(5):443–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilton R. Putting policy into practice? Poverty and people with serious mental illness. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(1):25–39. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JD, Buscemi J, Milsom V, Malcolm R, O’Neil PM. Effects on cardiovascular risk factors of weight losses limited to 5–10% Behav Med Pract Policy Res. 2016;6(3):339–46. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0353-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein DJ. Beneficial health effects of modest weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 1992;16(6):397–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens VJ, Obarzanek E, Cook NR, Lee I-M, Appel LJ, West DS, et al. Long-term weight loss and changes in blood pressure: results of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase II. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(1):1–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Williamson DF. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program? HealthAff. 2012;31(1):67–75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1009. Project Hope. Epub2012/01/11 http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL, Boucher JL, Histon T, Caplan W, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(10):1755–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, Safford M, Knowler WC, Bertoni AG, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(7):1481–6. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGinty EE, Baller J, Azrin ST, Juliano-Bult D, Daumit GL. Interventions to address medical conditions and health-risk behaviors among persons with serious mental illness: a comprehensive review. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(1):96–124. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cabassa LJ, Ezell JM, Roberto Lewis-Fernández M. Lifestyle interventions for adults with serious mental illness: a systematic literature review. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(8):774–82. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.8.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galletly CL, Murray LE. Managing weight in persons living with severe mental illness in community settings: a review of strategies used in community interventions. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30(11):660–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Hetrick SE, González-Blanch C, Gleeson JF, McGorry PD. Non-pharmacological management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(2):101–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.042853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernández-San-Martín MI, Martín-López LM, Masa-Font R, Olona-Tabueña N, Roman Y, Martin-Royo J, et al. The effectiveness of lifestyle interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with severe mental disorders: meta-analysis of intervention studies. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50(1):81–95. doi: 10.1007/s10597-013-9614-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruins J, Jörg F, Bruggeman R, Slooff C, Corpeleijn E, Pijnenborg M. The effects of lifestyle interventions on (long-term) weight management, cardiometabolic risk and depressive symptoms in people with psychotic disorders: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e112276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Gaal L, Wauters M, De Leeuw I. The beneficial effects of modest weight loss on cardiovascular risk factors. Int J Obes Metab Disord. 1997;21(Suppl. 1):S5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avenell A, Broom J, Brown T, Poobalan A, Aucott L, Stearns S, et al. Systematic review of the long-term effects and economic consequences of treatments for obesity and implications for health improvement. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(21) doi: 10.3310/hta8210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaughn MG, Howard MO. Integrated psychosocial and opioid-antagonist treatment for alcohol dependence: a systematic review of controlled evaluations. Soc Work Res. 2004;28(1):41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarrier N, Wykes T. Is there evidence that cognitive behaviour therapy is an effective treatment for schizophrenia? A cautious or cautionary tale? Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(12):1377–401. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cabassa LJ, Camacho D, Velez-Grau CM, Stefancic A. Peer-based health interventions for people with serious mental illness: a systematic literature review. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whiteman KL, Naslund JA, DiNapoli EA, Bruce ML, Bartels SJ. Systematic review of integrated general medical and psychiatric self-management interventions for adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2016 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500521. appi. ps. 201500521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Marsch LA, McHugo GJ, Bartels SJ. Crowdsourcing for conducting randomized trials of Internet delivered interventions in people with serious mental illness: a systematic review. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;44:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration: Wiley Online Library. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Follmann D, Elliott P, Suh I, Cutler J. Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(7):769–73. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90054-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartels SJ, Pratt SI, Aschbrenner KA, Barre LK, Naslund JA, Wolfe RS, et al. Pragmatic replication trial of health promotion coaching for obesity in serious mental illness and maintenance of outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(4):344–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14030357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faraone SV. Interpreting estimates of treatment effects: implications for managed care. Pharm Ther. 2008;33(12):700–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartels SJ, Pratt SI, Aschbrenner KA, Barre LK, Jue K, Wolfe RS, et al. Clinically significant improved fitness and weight loss among overweight persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(8):729–36. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.003622012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown C, Goetz J, Hamera E, Gajewski B. Treatment response to the RENEW weight loss intervention in schizophrenia: impact of intervention setting. Schizophr Res. 2014;159(2):421–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daumit GL, Dickerson FB, Wang N-Y, Dalcin A, Jerome GJ, Anderson CA, et al. A behavioral weight-loss intervention in persons with serious mental illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1594–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iglesias-García C, Toimil-Iglesias A, Alonso-Villa MJ. Pilot study of the efficacy of an educational programme to reduce weight, on overweight and obese patients with chronic stable schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17(9):849–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lovell K, Wearden A, Bradshaw T, Tomenson B, Pedley R, Davies LM, et al. An exploratory randomized controlled study of a healthy living intervention in early intervention services for psychosis: the INTERvention to encourage ACTivity, improve diet, and reduce weight gain (INTERACT) study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(5):498–505. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masa-Font R, Fernández-San-Martín M, López LM, Muñoz AA, Canet SO, Royo JM, et al. The effectiveness of a program of physical activity and diet to modify cardiovascular risk factors in patients with severe mental illness after 3-month follow-up: CAPiCOR randomized clinical trial. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(8):1028–36. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ratliff JC, Palmese LB, Tonizzo KM, Chwastiak L, Tek C. Contingency management for the treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized controlled pilot study. Obes Facts. 2012;5(6):919–27. doi: 10.1159/000345975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weber M, Wyne K. A cognitive/behavioral group intervention for weight loss in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2006;83(1):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brar JS, Ganguli R, Pandina G, Turkoz I, Berry S, Mahmoud R. Effects of behavioral therapy on weight loss in overweight and obese patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(2):205–12. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Methapatara W, Srisurapanont M. Pedometer walking plus motivational interviewing program for Thai schizophrenic patients with obesity or overweight: a 12-week, randomized, controlled trial. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(4):374–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu R-R, Zhao J-P, Jin H, Shao P, Fang M-S, Guo X-F, et al. Lifestyle intervention and metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(2):185–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.56-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldberg RW, Reeves G, Tapscott S, Medoff D, Dickerson F, Goldberg AP, et al. “MOVE!”: outcomes of a weight loss program modified for veterans with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(8):737–44. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Erickson ZD, Mena SJ, Pierre JM, Blum LH, Martin E, Hellemann GS, et al. Behavioral interventions for antipsychotic medication-associated obesity: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(2):183–9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu M-K, Wang C-K, Bai Y-M, Huang C-Y, Lee S-D. Outcomes of obese, clozapine-treated inpatients with schizophrenia placed on a six-month diet and physical activity program. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(4):544–50. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Green CA, Janoff SL, Yarborough BJH, Yarborough MT. A 12-week weight reduction intervention for overweight individuals taking antipsychotic medications. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50(8):974–80. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9716-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green CA, Yarborough BJH, Leo MC, Yarborough MT, Stumbo SP, Janoff SL, et al. The STRIDE weight loss and lifestyle intervention for individals taking antipsychotic medications: a randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):71–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lowe T, Lubos E. Effectiveness of weight management interventions for people with serious mental illness who receive treatment with atypical antipsychotic medications. A literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15(10):857–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Green CA, Yarborough BJH, Leo MC, Stumbo SP, Perrin NA, Nichols GA, et al. Weight maintenance following the STRIDE lifestyle intervention for individuals taking antipsychotic medications. Obesity. 2015;23(10):1995–2001. doi: 10.1002/oby.21205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alvarez-Jimenez M, González-Blanch C, Crespo-Facorro B, Hetrick S, Rodriguez-Sanchez JM, Perez-Iglesias R, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain in chronic and first-episode psychotic disorders. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(7):547–62. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parsons B, Allison DB, Loebel A, Williams K, Giller E, Romano S, et al. Weight effects associated with antipsychotics: a comprehensive database analysis. Schizophr Res. 2009;110(1):103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gates J, Killackey E, Phillips L, Alvarez-Jimenez M. Mental health starts with physical health: current status and future directions of non-pharmacological interventions to improve physical health in first-episode psychosis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(8):726–42. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Scherer EA, Pratt SI, Bartels SJ. Health promotion for young adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2016 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600091. appi. ps. 201600091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Firth J, Cotter J, Elliott R, French P, Yung A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. Psychol Med. 2015;45(07):1343–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714003110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Pratt SI, Lohman MC, Scherer EA, McHugo GJ, et al. Association between cardiovascular risk and depressive symptoms among people with serious mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stubbs B, Rosenbaum S, Vancampfort D, Ward PB, Schuch FB. Exercise improves cardiorespiratory fitness in people with depression: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:249–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]