Abstract

Background

Recently, Balkan virus (BALKV, family Phenuiviridae, genus Phlebovirus) was discovered in sand flies collected in Albania and genetically characterised as a member of the Sandfly fever Naples species complex. To gain knowledge concerning the geographical area where exposure to BALKV exists, entomological surveys were conducted in 2014 and 2015, in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BH), Kosovo, Republic of Macedonia and Serbia.

Results

A total of 2830 sand flies were trapped during 2014 and 2015 campaigns, and organised as 263 pools. BALKV RNA was detected in four pools from Croatia and in one pool from BH. Phylogenetic relationships were examined using sequences in the S and L RNA segments. Study of the diversity between BALKV sequences from Albania, Croatia and BH showed that Albanian sequences were the most divergent (9–11% [NP]) from the others and that Croatian and BH sequences were grouped (0.9–5.4% [NP]; 0.7–5% [L]). The sand fly infection rate of BALKV was 0.26% in BH and 0.27% in Croatia. Identification of the species content of pools using cox1 and cytb partial regions showed that the five BALKV positive pools contained Phlebotomus neglectus DNA; in four pools, P neglectus was the unique species, whereas P. tobbi DNA was also detected in one pool.

Conclusions

We report here (i) the first direct evidence that the Balkan virus initially described in coastal Albania has a much wider dissemination area than originally believed, (ii) two real-time RT-PCR assays that may be useful for further screening of patients presenting with fever of unknown origin that may be caused by Balkan virus infection, (iii) entomological results suggesting that Balkan virus is likely transmitted by Phlebotomus neglectus, and possibly other sand fly species of the subgenus Larroussius. So far, BALKV has been detected only in sand flies. Whether BALKV can cause disease in humans is unknown and remains to be investigated.

Keywords: Bunyaviridae, Phlebovirus, Arbovirus, Toscana virus, Meningitis, Fever, Sand fly, Phlebotomus, Phylogeny, Emergence

Background

Phleboviruses (family Phenuiviridae) are arthropod-borne viruses transmitted by mosquitoes, ticks and sand flies to vertebrate hosts [1]. Several phleboviruses belong to the Sandfly fever Naples species complex (which include at least two human pathogens, namely Toscana virus causing neurological infections and Naples virus causing incapacitating febrile illness) [2]. In the Old World, sand fly-borne phleboviruses are transmitted by Phlebotomus spp. and Sergentomyia spp. and show a wide distribution in all countries of the Mediterranean basin [2], http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/vectors/vector-maps/Pages/VBORNET_maps_sandflies.aspx. During the last decade, several new phleboviruses were discovered in Mediterranean countries either in sand flies [3–9] or clinical samples [10]. Each was genetically related to any of the three following groups (based on antigenic relationships): Sandfly fever Naples species, Salehabad and Sandfly fever Sicilian/ Corfou virus group. In the Balkans, the current knowledge on circulating phleboviruses is limited. Recently, the Balkan virus (BALKV) was discovered in sand flies collected in Albania and genetically characterised as a member of the Sandfly fever Naples species complex [11]. Two specific quantitative real-time RT-PCR assays were designed to screen entomological specimens collected in the surrounding countries, i.e. Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BH), Kosovo, Republic of Macedonia (RoM), and Serbia, to gain knowledge concerning the geographical area where exposure to BALKV exists.

Methods

Sand flies were collected in the field in 2014; 10 stations in Kosovo and 8 stations in Serbia, in 2015; 5 stations in Croatia, 6 stations in BH, 5 stations in RoM, 1 station in Montenegro and 1 station in Serbia (Table 1) using a previously described method [11]. Traps were placed near animals with the consent of the owners. BALKV RNA was detected using 2 SYBR Green real-time RT-PCR specific assays targeting the polymerase gene (BALKV-L-F; 5′-CTD ATY AGY TGC TGC TAC AAT G-3′, BALKV-L-R; 5′-CCA TAA CCA AGA TAY TCA T-3′) and the nucleoprotein gene (BALKV-S-F; 5′-AGA GTR TCT GCA GCC TTT GTT CC-3′, BALKV-S-R; 5′-CAG CTA TCT CAT TAG GYT GT-3′). The cycling program consisted of 50 °C for 30 min and 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s, with a final melting curve step at 95 °C for 1 min, 60 °C 30 s and 95 °C for 30 s. Melting curves for positives were at 75 °C for the polymerase assay and 79.5 °C for the nucleoprotein test.

Table 1.

Trapping campaigns and geographical information of the Balkan virus positive pools

| Trapping region | Number of collected sand flies | No. of pools (positive pools_gender) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Mix/unknown | ||

| 2014: Kosovo | ||||

| Vermice | 12 | 16 | 4 | 6 |

| Zhur | 10 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Landrovice | 11 | 14 | 2 | 6 |

| Krusha E. Vogel | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Junik | 28 | 27 | 3 | 7 |

| Donji Livoc | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cernice | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Nishor | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| Studencan | 18 | 11 | 2 | 6 |

| Semetiste | 50 | 43 | 2 | 12 |

| Total | 134 | 119 | 17 | 48 |

| 2014: Serbia | ||||

| Aleksinac / Kraljevo | 8 | 8 | 0 | 2 |

| Brest | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Arbanasce | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Prugovac | 5 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| Subotinac | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Mozgovo | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Bovan | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Jugbogdanovac | 8 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 34 | 18 | 1 | 13 |

| 2015: Bosnia and Herzegovina | ||||

| Sovici | 105 | 77 | 0 | 11//(#B1_male) |

| Mikanjici | 22 | 18 | 0 | 4 |

| Zakovo | 10 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Grab | 47 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Stolac | 55 | 44 | 0 | 7 |

| Tuli | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 239 | 147 | 0 | 19 |

| 2015: Croatia | ||||

| Duba | 176 | 129 | 30 | 18/(#C13_male) |

| Jesenice | 81 | 0 | 25 | 6 |

| Gorna Ljuta | 22 | 18 | 2 | 4 |

| Zvekovica | 12 | 9 | 0 | 3 |

| Vidonje | 490 | 55 | 404 | 47/(#C41, #C50, #C51_females) |

| Total | 781 | 211 | 461 | 78 |

| 2015: Montenegro | ||||

| Ozrinici | 21 | 14 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 21 | 14 | 2 | 4 |

| 2015 Romania | ||||

| Mokrino | 48 | 91 | 3 | 26 |

| Kezhovica | 85 | 10 | 42 | 15 |

| Dedeli | 25 | 7 | 1 | 10 |

| Suvo Grlo | 274 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| Furka | 11 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 443 | 112 | 47 | 85 |

| 2015: Serbia | ||||

| Krasava | 19 | 9 | 1 | 16 |

| Total | 19 | 9 | 1 | 16 |

| Grand total | 1671 | 630 | 529 | 263 |

Phylogenetic relationships were reconstructed using sequences of the S and L RNA segments. Positive samples were PCR-amplified targeting a portion of the polymerase [12] and the nucleoprotein genes [13, 14] (two systems producing overlapping sequences which were concatenated before analysis). Sand fly species identification within positive pools was performed using as previously described cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) and cytochrome b (cytb) barcoding gene regions followed by NGS sequencing of the corresponding PCR products [11]. A 50 μl-volume of BALKV positive pools was inoculated onto Vero cells for attempting virus isolation [7, 9].

Results

In 2014 a total of 270 and 53 sand flies were collected from Kosovo and Serbia, respectively. In 2015, 1453, 386, 37, 602 and 29 sand flies were trapped in Croatia, BH, Montenegro, RoM and Serbia, respectively (Table 1). BALKV RNA was detected in 4 pools from Croatia (3 collected in Vidonje [C41, C50, C51 at 42.98244N, 17.64294E (240 m)], 1 in Duba [C13 at 42.60032N, 18.33946E (475 m)]) and in 1 pool from BH in Sovici (B1 at 43.408240N, 17.329175E, 283 m) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of the sand fly trapping stations. Black circles denote trapping stations. Red circles denote trapping stations in which at least one pool was found to contain Balkan virus RNA

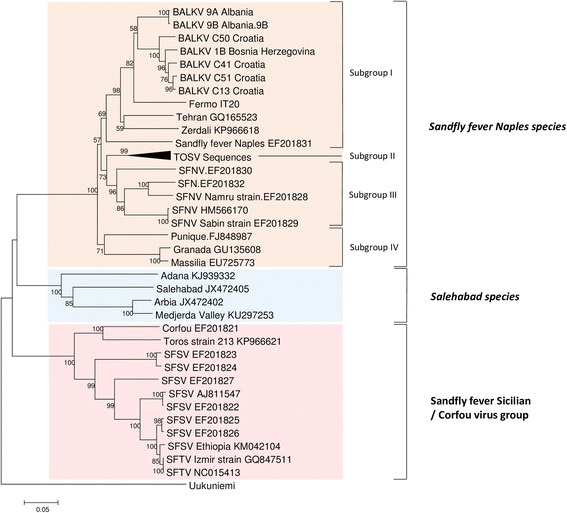

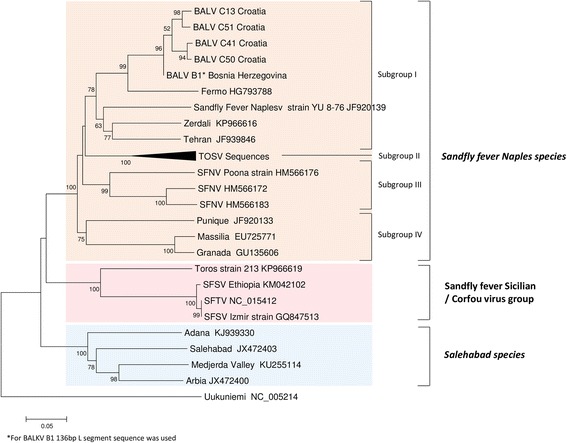

Although not quantitative, the low Ct values observed with the polymerase gene (Ct range 19.9–24.4) and the nucleoprotein gene (Ct range 19.8–32.8) SYBR Green real-time RT-PCR was indicative of high viral load in the positive pools. Phylogeny was reconstructed by using sequences in the S and L RNA segments that were 572 nt (Fig. 2) and 525 nt long, respectively (Fig. 3). Identical groupings were observed using both markers. BALKV formed a homogenous cluster with common ancestor supported by a high bootstrap value. BALKV was included in the subgroup I of the Sandfly fever Naples species complex together with SFNV, Tehran, Zerdali and Fermo viruses.

Fig. 2.

Phylogeny of the Balkan virus and closely related phleboviruses using partial nucleotide sequences of the nucleoprotein gene (572 nt). Neighbor-joining analysis (Kimura 2-parameter model) was performed using MEGA6, with 1000 bootstrap replicates

Fig. 3.

Phylogeny of the Balkan virus and closely related phleboviruses using partial nucleotide sequences of the polymerase gene (525 nt). Neighbor-joining analysis (Kimura 2-parameter model) was performed using MEGA6, with 1000 bootstrap replicates

For pool B1, failure to obtain a positive PCR with Nphlebo primers led us to sequence the 136 bp SYBR Green RT-qPCR product for genetic and phylogenetic analysis. Study of the diversity between BALKV sequences from Albania, Croatia and BH showed that (i) Albanian sequences were the most divergent (9–11% [NP]) from the others, and (ii) that Croatian and BH sequences were grouped (0.9–5.4% [NP]; 0.7–5% [L]) (GenBank: KY662276–KY662287).

Identification of the sand fly species contained in the BALKV-positive pools detected Phlebotomus neglectus sequences in all five pools; P. neglectus was the unique species in four pools, whereas P. tobbi DNA was present in 1 pool from Croatia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Details of the Balkan virus positive pools with sandfly species identification using cytochrome b and cox1 sequences

| Trapping locality | Pool code | Sand fly species | Gene | Reads | No. of sand flies | Gender | Collection date | Altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | ||||||||

| Sovici | B1 | P. neglectus | cytb | 1427 | 27 | male | 06/07/2015 | 283 |

| cox1 | 4257 | |||||||

| Croatia | ||||||||

| Duba | C13 | P. tobbi | cytb | 1211 | 20 | male | 13/07/2015 | 475 |

| cox1 | 546 | |||||||

| P. neglectus | cytb | 967 | ||||||

| cox1 | 7351 | |||||||

| Vidonje | C41 | P. neglectus | cytb | 950 | 20 | female | 16/07/2015 | 240 |

| cox1 | 8182 | |||||||

| Vidonje | C50 | P. neglectus | cytb | 1834 | 20 | female (bf) | 16/07/2015 | 240 |

| cox1 | 5302 | |||||||

| Vidonje | C51 | P. neglectus | cytb | 3143 | 20 | female (bf) | 16/07/2015 | 240 |

| cox1 | 22,867 | |||||||

Discussion

The Balkan Peninsula is the region where sand fly fever was first described at the end of the nineteenth century in BH [15, 16]. Subsequent studies provided direct and indirect evidence for the presence of viruses belonging to the SFNV in BH [17–21]. In Croatia, antibodies against SFNV were found in human populations, with highest rates (up to 53.9%) observed on islands and in coastal regions [18, 22–27]. BALKV belongs to the Sandfly fever Naples species complex where it is most closely to Fermo, SFNV YU 8–76, Zerdali and Tehran viruses isolated in Italy, Serbia, Turkey and Iran which are grouped in the subgroup I [6, 9, 19, 28] (Figs. 2, 3). BALKV was first detected from two sand fly pools from Albania, Kruje region [11]. Here, we demonstrated that BALKV has a much larger circulation area that seems to be confined to the Adriatic coast of the Balkan Peninsula. This merits further confirmation through similar studies conducted north and south of the current study area (Fig. 1).

To our knowledge, BALKV is the first phlebovirus to be genetically identified in BH. Assuming that each positive pool contained one infected sand fly only, the sand fly infection rate of BALKV is 0.26% in BH and 0.27% in Croatia; which is higher than Zerdali virus (0.035%) and similar to Fermo virus (0.20%) [6, 9]. Identification of the species content of pools using cox1 and cytb showed that P. neglectus is the only species to be found in all BALKV RNA positive pools; indicating that this species might be the vector of BALKV. Interestingly, P. neglectus belongs to subgenus Larroussius, similar to P. tobbi which seems to be a typical vector for Zerdali virus, another member of the Sandfly fever Naples species [9]. Together, these data support the hypothesis that Larroussius sand flies are typical vectors of the members of this virus group.

Conclusions

We report here (i) the first direct evidence that Balkan virus initially described in Coastal Albania has a much wider dissemination area than originally believed, (ii) two real-time RT-PCR assays that may be useful for further screening of patients presenting with fever of unknown origin that may be caused by Balkan virus infection, (iii) entomologic results suggesting that Balkan virus is likely transmitted by Phlebotomus neglectus, and possibly other sand fly species of the subgenus Larroussius. So far, BALKV has been detected only in sand flies. Whether BALKV can cause disease in humans is unknown and remains to be investigated.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Karine Almani for excellent technical assistance. The work of RNC was done under the frame of EurNegVec (TD1303) COST Action. NA is a PhD student supported by a grant from Fondation Mediterranee Infection.

Funding

This work was supported by funds received from (i) VectorNet, a European network for sharing data on the geographic distribution of arthropod vectors, transmitting human and animal disease agents (Contract OC/EFSA/ AHAW/2013/02-FWC1) funded by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) (http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/vectors/VectorNet/Pages/VectorNet.aspx), (ii) the European Virus Archive goes Global (EVAg) project in the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 653316 (http://global.european-virus-archive.com/). Nazli Ayhan is a PhD student supported by a grant from Fondation Mediterranee Infection. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Sequences generated in this study are available in the GenBank database under the accession numbers KY662276–KY662287.

Abbreviations

- BALKV

Balkan virus

- BH

Bosnia and Herzegovina

- L

Large RNA segment

- NGS

Next generation sequencing

- NP

Nucleoprotein

- RoM

Republic of Macedonia

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- S

Small RNA segment

Authors’ contributions

NA participated in field work, performed PCR and sequencing, and wrote the original MS; BA, VI, FM, JO, JS, DP, DB and PV organized and participated in the field work; VD set-up of PCR-based NGS identification of sand flies; SV participated to field work, performed PCR-based NGS identification; RNC analysed results, and coordinated the lab work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Traps were placed near animals with the consent of the owners.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nazli Ayhan, Email: nazliayhann@gmail.com.

Bulent Alten, Email: kaynas@hacettepe.edu.tr.

Vladimir Ivovic, Email: ivovic.v@gmail.com.

Vit Dvořák, Email: icejumper@seznam.cz.

Franjo Martinkovic, Email: fmartinkovic@gmail.com.

Jasmin Omeragic, Email: jasmin.omeragic@vfs.unsa.ba.

Jovana Stefanovska, Email: jstefanovska@fvm.ukim.edu.mk.

Dusan Petric, Email: dusanp@polj.uns.ac.rs.

Slavica Vaselek, Email: slavica.vaselek@gmail.com.

Devrim Baymak, Email: devrimbaymak@gmail.com.

Ozge E. Kasap, Email: ozgeerisoz@yahoo.com

Petr Volf, Email: volf@cesnet.cz.

Remi N. Charrel, Email: remi.charrel@univ-amu.fr

References

- 1.Depaquit J, Grandadam M, Fouque F, Andry PE, Peyrefitte C. Arthropod-borne viruses transmitted by phlebotomine sand flies in Europe: a review. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(10):19507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkan C, Bichaud L, de Lamballerie X, Alten B, Gould EA, Charrel RN. Sandfly-borne phleboviruses of Eurasia and Africa: epidemiology, genetic diversity, geographic range, control measures. Antivir Res. 2013;100(1):54–74. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charrel RN, Moureau G, Temmam S, Izri A, Marty P, Parola P, et al. Massilia virus, a novel Phlebovirus (Bunyaviridae) isolated from sandflies in the Mediterranean. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9(5):519–530. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2008.0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhioua E, Moureau G, Chelbi I, Ninove L, Bichaud L, Derbali M, et al. Punique virus, a novel phlebovirus, related to sandfly fever Naples virus, isolated from sandflies collected in Tunisia. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(5):1275–1283. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.019240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papa A, Velo E, Bino S. A novel phlebovirus in Albanian sandflies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(4):585–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remoli ME, Fortuna C, Marchi A, Bucci P, Argentini C, Bongiorno G, et al. Viral isolates of a novel putative phlebovirus in the Marche Region of Italy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90(4):760–763. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alkan C, Alwassouf S, Piorkowski G, Bichaud L, Tezcan S, Dincer E, et al. Isolation, genetic characterization, and seroprevalence of Adana virus, a novel phlebovirus belonging to the Salehabad virus complex, in Turkey. J Virol. 2015;89(8):4080–4091. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03027-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amaro F, Hanke D, Zé-Zé L, Alves MJ, Becker SC, Höper D. Genetic characterization of Arrabida virus, a novel phlebovirus isolated in South Portugal. Virus Res. 2016;214:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alkan C, Erisoz Kasap O, Alten B, de Lamballerie X, Charrel RN. Sand fly-borne phlebovirus isolations from Turkey: new insight into the sandfly fever Sicilian and sandfly fever Naples species. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(3):e0004519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anagnostou V, Pardalos G, Athanasiou-Metaxa M, Papa A. Novel phlebovirus in febrile child, Greece. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(5):940–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Ayhan N, Velo E, de Lamballerie X, Kota M, Kadriaj P, Ozbel Y, et al. Detection of Leishmania infantum and a novel phlebovirus (Balkan Virus) from sand flies in Albania. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016;16(12):802–806. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sánchez-Seco MP, Echevarría JM, Hernández L, Estévez D, Navarro-Marí JM, Tenorio A. Detection and identification of Toscana and other phleboviruses by RT-nested-PCR assays with degenerated primers. J Med Virol. 2003;71(1):140–149. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charrel RN, Izri A, Temmam S, Delaunay P, Toga I, Dumon H, et al. Cocirculation of 2 genotypes of Toscana virus, southeastern France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(3):465–468. doi: 10.3201/eid1303.061086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambert AJ, Lanciotti RS. Consensus amplification and novel multiplex sequencing method for S segment species identification of 47 viruses of the Orthobunyavirus, Phlebovirus, and Nairovirus genera of the family Bunyaviridae. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(8):2398–2404. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00182-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pick A. Zur Pathologie und Therapie einer eigenthümlichen endemischen Krankheitsform. Wien Med Wschr. 1886;33:1141–1145. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pick A. Beiträge zur Pathologie und Therapie einer eigenthümlichen Krankheitsform (Gastro-enteritis climatica) Prager Med Wschr. 1887;12:364. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terzin AL, Matuka S, Fornazarić MR, Hlača DM. Antibodies against some arboviruses and against the Bedsonia antigen in sera of men, sheep and cattle in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Acta Medica Yugoslavica. 1962;16(3–4):301–317. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vesenjak-Hirjan J. Arboviruses in Yugoslavia. In: Vesenjak-Hirjan J, editor. Arboviruses in the Mediterranean countries. Stuttgart-New York: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1980. pp. 165–177. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gligić A, Mišcević Z, Tesh RB, Travassos da Rosa A, Zivković V. First isolations of Naples sandfly fever virus in Yugoslavia. Mikrobiologija. 1982;19:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hukić M, Salimović-Besić I. Sandfly-Pappataci fever in Bosnia and Herzegovina: the new-old disease. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2009;9(1):39–43. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2009.2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hukić M, Numanović F, Sisirak M, Moro A, Dervović E, Jakovec S, Besić IS. Surveillance of wildlife zoonotic diseases in the Balkans Region. Med Glas (Zenica) 2010;7(2):96–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tesh RB, Saidi S, Gajdamovic SJ, Rodhain F, Vesenjak-Hirjan J. Serological studies on the epidemiology of sandfly fever in the old world. Bull World Health Organ. 1976;54(6):663–674. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vesenjak-Hirjan J, Punda-Polić V, Dobe M. Geographical distribution of arboviruses in Yugoslavia. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1991;35(2):129–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borcić B, Punda V. Sandfly fever epidemiology in Croatia. Acta Med Iugosl. 1987;41(2):89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Punda-Polić V, Calisher CH, Vesenjak-Hirjan J. Neutralizing antibodies for sandfly fever Naples virus in human sera on the island of Mljet. Acta Med Iugosl. 1990;44(1):15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Punda-Polić V, Mohar B, Duh D, Bradarić N, Korva M, Fajs L, et al. Evidence of an autochthonous Toscana virus strain in Croatia. J Clin Virol. 2012;55(1):4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Punda-Polić V, Jerončić A, Mohar B, Šiško KK. Prevalence of Toscana virus antibodies in residents of Croatia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(6):E200–E203. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karabatsos N. Supplement to International Catalogue of Arboviruses including certain other viruses of vertebrates. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:372. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Sequences generated in this study are available in the GenBank database under the accession numbers KY662276–KY662287.