Abstract

Natriuretic peptides (NP) are cardiac-derived hormones with favorable cardiometabolic actions. Low NP levels are associated with increased risks of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, conditions with variable prevalence by race/ethnicity. Heritable factors underlie a significant proportion of the inter-individual variation in NP concentrations, but the specific influences of race and ancestry are unknown. In 5,597 individuals (40% White, 24% Black, 23% Hispanic, and 13% Chinese) without prevalent cardiovascular disease at baseline in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, multivariable linear regression and restricted cubic splines were used to estimate differences in serum N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels according to race/ethnicity and ancestry. Ancestry was determined using genetic ancestry informative markers. NT-proBNP concentrations differed significantly by racial/ethnicity (Black, median 43 pg/ml [IQR 17–94], Chinese 43 [17–90], Hispanic 53 [23–107], White 68 [34–136]; P = 0.0001). In multivariable models, NT-proBNP was 44% lower (95% CI, −48 to −40) in Black and 46% lower (−50 to −41) in Chinese, compared with White individuals. Hispanic individuals had intermediate concentrations. Self-identified Blacks and Hispanics were the most genetically admixed. Among self-identified Black individuals, a 20% increase in genetic European ancestry was associated with 12% higher (1 to 23%) NT-proBNP. Among Hispanic individuals, genetic European and African ancestry were positively and negatively associated with NT-proBNP levels, respectively. In conclusion, NT-proBNP levels differ according to race/ethnicity, with the lowest concentrations in Black and Chinese individuals. Racial/ethnic differences in NT-proBNP may have a genetic basis, with European and African ancestry associated with higher and lower NT-proBNP concentrations, respectively.

Keywords: natriuretic peptide, race, admixture, genetics

Introduction

Natriuretic peptides (NP) are cardiac-derived hormones with beneficial cardiometabolic effects including natriuresis, diuresis, vasodilation, insulin sensitivity, and lipolysis.1,2 Animal and human studies demonstrate that relative NP deficiencies are associated with the development of salt-sensitive hypertension, insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus, and obesity.3–8 These cardiovascular risk factors disproportionately affect certain races/ethnicities, suggesting that relatively low NP concentrations may contribute to racial differences in susceptibility to cardiometabolic disease9,10 However, whether NPs concentrations differ between racial/ethnic groups, with relatively low concentrations corresponding with those groups carrying the highest burden of cardiometabolic disease, has not been completely characterized.11–13 Furthermore, a substantial proportion of the inter-individual variation in circulating NP concentrations has been attributed to genetic factors.14 Whether genetic ancestry is also associated with NP concentrations has not been comprehensively examined. In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), we tested whether N-terminal pro B-type NP (NT-proBNP) concentrations differed between White, Black, Chinese, and Hispanic individuals. We also examined the associations between genetic ancestry and NT-proBNP concentrations.

Methods

MESA is an ongoing, prospective observational study of subclinical cardiovascular disease and risk factors, for which detailed methods have been previously published.15 Briefly, between July 2000 and July 2002, 6,814 asymptomatic men and women aged 45 to 84 years and without prevalent cardiovascular disease were recruited from 6 communities in the United States (Forsyth County, NC; Northern Manhattan and the Bronx, NY; Baltimore and Baltimore County, MD; St. Paul, MN; Chicago, IL; and Los Angeles County, CA). Each site enrolled an approximately equal number of men and women according to pre-specified age and race/ethnicity proportions (39% White, 28% Black, 22% Hispanic, and 12% Chinese). The final study cohort for this analysis included 5,597 individuals in whom NT-proBNP was measured at baseline, as described below.16 Institutional review boards from each site approved the study and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Race/ethnicity was self-reported as White, Chinese, Black, or Hispanic. Conventional definitions for hypertension (blood pressure > 140/90 mmHg or anti-hypertensive medication use) and diabetes mellitus (fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL or anti-diabetic medication use) were used. Heart rate, blood pressure, height and weight were measured using standardized protocols. Education and income were self-reported. The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as fasting insulin (μIU/ml) x fasting glucose (mmol/l)/22.5.17 Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the CKD-Epi equation and urinary albumin/creatinine was measured using nephelometry and the rate Jaffe reaction (Clinical Chemistry Laboratory, Fletcher Allen Health Care, Burlington, VT).18 Left ventricular mass and ejection fraction were calculated from offline analysis of short-axis, breath-hold, electrocardiographic-gated cine cardiac magnetic resonance images obtained on 1.5-T MRI scanners (Siemens Medical Systems, Malvern, PA; GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI) in a subset of participants (n=4,162).16

Serum NT-proBNP concentrations were determined from samples drawn at baseline that were frozen and stored at −70°C. All measurements were performed in a CLIA certified laboratory at the Veteran’s Affairs San Diego Healthcare System (La Jolla, CA), using the Elecsys 2010 proBNP platform (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were: at 175 pg/ml, 2.7% and 3.2%; at 355 pg/ml 2.4% and 2.9%; at 1,068 pg/ml, 1.9% and 2.6%, and at 4,962 pg/ml 1.8% and 2.3%. The limits of detection were 5 and 35,000 pg/ml.16

Genotyping methods for estimating genetic ancestry have previously been reported in MESA.19,20 Briefly, two sets of ancestry proportion estimates were computed; the first included individuals who self-reported race/ethnicity as either White or Black. These estimates were computed assuming 2 ancestral populations (central European and West African Yoruban) using 300 markers. The second set of ancestry estimates was computed based upon several genome-wide admixture panels for Hispanic and Chinese individuals. Panels 1 and 2 were then combined into a single list, which were examined on the Affymetrix AFFY 6.0 chip. Ancestry proportion was estimated from 406 identified SNPs using the software ADMIXMAP, which allows for the direct inclusion of ancestral allele frequencies.

For statistical analyses, participants were categorized according to self-reported race/ethnicity. Summary statistics were calculated as counts (%) and medians (25th,75th percentiles) for categorical and continuous data, respectively. Unadjusted NT-proBNP concentrations were compared across groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The frequency of NT-proBNP levels below detection limit were compared between racial/ethnic groups using the χ2 test. NT-proBNP values were natural log transformed prior to entry into regression models. Sequential multivariable-adjusted linear regression models were used to assess the associations between race/ethnicity (independent) and natural log transformed NT-proBNP concentrations (dependent). The multiplicative effect (% difference) on NT-proBNP concentrations was estimated as (eβ-1) x 100, where β is the coefficient from linear regression models. Covariates in multivariable-adjusted models were selected a priori and included: age, sex, anti-hypertensive medication use, diabetes mellitus, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, BMI, eGFR, urine albumin to creatinine ratio, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, annual household income, education, left ventricular ejection fraction and left ventricular mass. In additional analyses, HOMA-IR was included in multivariable models among individuals without diabetes mellitus. Interaction terms to assess for effect modification by age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and chronic kidney disease were also included. Within each self-reported race/ethnicity, multivariable linear regression and restricted cubic spline analyses with three knots were used including proportion genetic ancestry as the primary independent variable with adjustment for covariates listed above. The number of knots was selected based upon the model that produced the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). All analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). For all statistical tests, 2-sided P values <0.05 were considered significant without adjustment for multiple testing.

Results

Of the 6,814 MESA baseline participants, 1,217 were excluded due to lack of NT-proBNP measures. Compared with the excluded, the cohort of included participants (n = 5,597) was slightly older (median 63 vs. 61 years), with fewer women (51% vs. 59%), fewer Blacks (24% vs. 44%), and less hypertension (48% vs. 52%), while other baseline characteristics, such as diabetes, renal function, LV mass index, and LVEF were similar (data not shown).

The included study sample was 40% White, 24% Black, 23% Hispanic, and 13% Chinese (Table 1). Hypertension was most common among Blacks, while diabetes mellitus was most common among Black and Hispanic individuals. Chinese individuals had the lowest BMI, but were more insulin resistant compared with White individuals. Hispanic individuals were the most insulin resistant. Unadjusted NT-proBNP concentrations were lowest in Black (median 43 [25th–75th percentiles, 17 – 94] pg/ml) and Chinese individuals (43 [17 – 90]), highest among White individuals (68 [34 – 136]), and intermediate among Hispanics (53 [23 – 107]) (P = 0.0001). NT-proBNP concentrations below the limit of detection (< 5 pg/ml) were also more common among Black and Chinese individuals compared with Whites and Hispanics, P < 0.001.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis participants by race/ethnicity.

| White | Chinese | Black | Hispanic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,217 (40%) | 742 (13%) | 1,353 (24%) | 1,285 (23%) | |

| Age (years) | 63 (54,71) | 63 (53,71) | 62 (53,70) | 62 (53,69) |

| Female | 1,122 (51%) | 375 (51%) | 725 (54%) | 660 (51%) |

| Hypertension | 979 (44%) | 298 (40%) | 819 (61%) | 576 (45%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 144 (7%) | 101 (14%) | 241 (18%) | 243 (19%) |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 62 (56,69) | 62 (57,69) | 62 (56,69) | 63 (57,69) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 121 (109,137) | 122 (109,138) | 130 (116,144) | 124 (111,140) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 70 (63,77) | 72 (65,79) | 74 (68,81) | 71 (65,78) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.2 (24.3,30.4) | 23.7 (21.8,26.2) | 29.4 (26.1,33.5) | 28.6 (26.0,31.8) |

| Income | ||||

| < $25k | 348 (16%) | 370 (50%) | 387 (31%) | 643 (51%) |

| $25–50k | 560 (26%) | 162 (22%) | 403 (32%) | 401 (32%) |

| > $50k | 1,257 (58%) | 207 (28%) | 477 (38%) | 210 (17%) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 87 (81,95) | 92 (86,101) | 91 (83,102) | 92 (84,105) |

| HOMA-IR | 1.57 (1.13,2.34) | 1.74 (1.32,2.52) | 1.88 (1.23,2.82) | 1.97 (1.39,3.10) |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 75 (66,84) | 81 (72,92) | 85 (74,97) | 82 (71,93) |

| Albuminuria | 135 (6%) | 92 (12%) | 156 (12%) | 158 (12%) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 115 (95,136) | 114 (96,132) | 115 (94,136) | 118 (98,139) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 114 (77,164) | 123 (87,172) | 90 (66,122) | 137 (97,196) |

| NT-proBNP (pg/ml)* | 68 (34,136) | 43 (17,90) | 43 (17,94) | 53 (23,107) |

| NT-proBNP < 5 pg/ml | 67 (3%) | 66 (9%) | 137 (10%) | 73 (6%) |

| LV mass index, (g/m2) | 74 (65,85) | 72 (65,81) | 80 (71,92) | 78 (69,90) |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 69 (64,74) | 73 (68,76) | 69 (63,74) | 70 (64,74) |

Data presented as number (percent) or median (25th, 75th percentiles). BMI = body mass index, BP = blood pressure, BPM = beats per minute, eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate, HOMA-IR = homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, LV = left ventricular, NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide. Total N for LVMI and LVEF = 4,162.

P = 0.0001 for differences in NT-proBNP by race/ethnicity. Total N for HOMA-IR = 4,831.

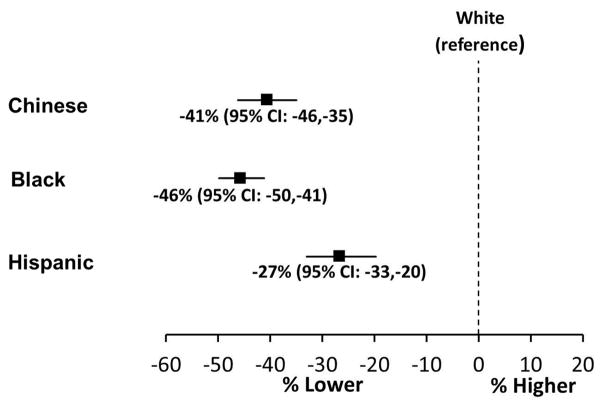

In multivariable models, adjusted NT-proBNP concentrations were 46% lower (95% CI: −50 to −41) in Black compared with White individuals (Figure 1). Adjustment for insulin resistance did not substantially attenuate the difference in NT-proBNP concentrations between Black and White participants (Table 2). NT-proBNP concentrations were 41% lower (95% CI: −46 to −35) in Chinese compared with White individuals (Figure 1). Hispanic individuals also had lower NT-proBNP concentrations (−27%, 95%CI: −35 to −20) compared with Whites. Interaction terms to test for modification of the association between race/ethnicity and NT-proBNP concentrations were not significant for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, or chronic kidney disease (P > 0.05 for all).

Figure 1. Multivariable adjusted percent differences in serum N terminus pro B type natriuretic peptide concentrations by self-reported race/ethnicity in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.

Data presented as point estimate (95% confidence interval). Adjusted for age, sex, anti-HTN medication use, diabetes mellitus, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, estimated glomerular filtration rate, urine albumin to creatinine ratio, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, education, income, left ventricular mass, and left ventricular ejection fraction. P <0.001 for all race/ethnic group comparisons with white individuals.

Table 2.

Multivariable-adjusted percent differences in N terminus-pro B type Natriuretic Peptide concentrations by race/ethnicity in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.

| Model | Covariates | White | Chinese | Black | Hispanic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age, sex | Reference | −38% (−43%, −33%) | −36% (−40%, −32%) | −21% (−26%, −15%) | |

| 2 | Model 1 + | Anti-hypertensive med, diabetes mellitus heart rate, systolic BP, body mass index, eGFR, UACR, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides | Reference | −42% (−46%, −37%) | −42% (−46%, −37%) | −18% (−23%, −12%) |

| 3 | Model 2 + | education, income | Reference | −46% (−50%, −41%) | −44% (−48%, −40%) | −25% (−30%, −19%) |

| 4 | Model 3 + | LV ejection fraction, LV mass index | Reference | −41% (−46%, −35%) | −46% (−50%, −41%) | −27% (−33%, −20%) |

| 5 | Model 4 + | HOMA-IR | Reference | −37% (−43%, −31%) | −45% (−49%, −39%) | −27% (−33%, −20%) |

Data presented as percent differences in serum NT-proBNP levels (95% confidence interval). eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HOMA-IR = homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; LDL = low density lipoprotein cholesterol; LV = left ventricular BP = blood pressure; UACR = urine albumin to creatinine ratio.

The analyses were repeated with restriction of the study sample to individuals with detectable levels of NT-proBNP (i.e. > 5 pg/ml), and the racial/ethnic differences persisted (Black: 35% lower [95% CI: −40 to −30]; Chinese: 32% lower [−38 to −26]; Hispanic 23% lower [−29 to −16] compared with White individuals). In the subset of healthy individuals (n = 784), defined as being lean (BMI < 25 kg/m2), without diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or renal dysfunction, and having LVEF ≥ 55%, NT-proBNP concentrations remained significantly lower in Black, Chinese, and Hispanic compared with White individuals (Black: −44% [95% CI: −57 to −27]; Chinese: −48% [−58 to −36]; Hispanic −34% [−49 to −14]).

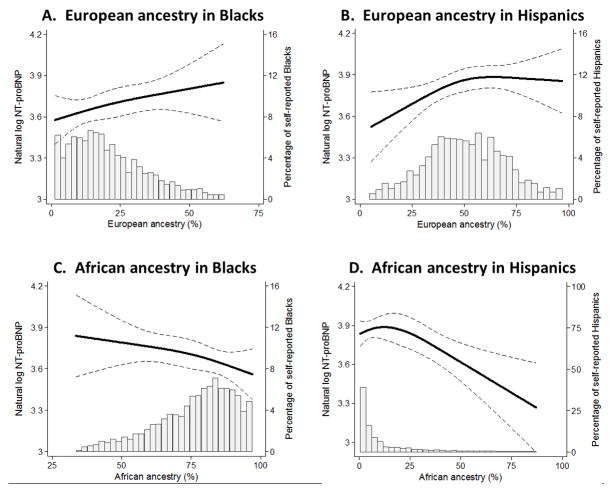

Among the 5,434 (97%) participants in whom genetic ancestry data were available, self-reported White and Chinese participants had the least genetic admixture, while Hispanic and Black individuals were the most genetically admixed (Table 3). In multivariable-adjusted linear regression analyses, among self-reported Blacks, a 20% increase in the proportion of European ancestry was associated with an 11.6% increase (95% CI: 1.1 to 23.3) in NT-proBNP concentration. Similarly, among self-reported Hispanic individuals, a 20% increase in European ancestry was associated with 7.4% (0.3 to 15.1) higher NT-proBNP levels. In contrast, a 20% increase African ancestry was associated with 10.4% (95% CI: −18.9 to −1.1) and 10.0% (−16.2 to −3.3) lower NT-proBNP levels among self-reported Black and Hispanic participants, respectively. Chinese ancestry was not associated with NT-proBNP concentrations among Hispanic individuals (−9.8% [95% CI −23.7 to 6.7) per 20% increase).

Table 3.

Proportion genetic ancestry according to self-reported race/ethnicity in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.

| Self-reported race/ethnicity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Chinese | Black | Hispanic | |

| Genetic ancestry | ||||

| European | 96.7% (94.7%, 97.9%) | 1.7% (1.1%, 2.8%) | 18.5% (10.6%, 30.5%) | 50.0% (37.4%, 63.9%) |

| Chinese | 0.6% (0.4%, 1.0%) | 95.5% (93.7%, 97.0%) | 0.8% (0.5%, 1.4%) | 2.3% (1.0%, 5.8%) |

| African | 1.6% (0.9%, 3.2%) | 1.0% (0.6%, 1.6%) | 79.1% (67.3%, 87.3%) | 4.7% (1.8%, 14.8%) |

| Hispanic | 0.4% (0.3%, 0.7%) | 0.7% (0.4%, 1.5%) | 0.6% (0.4%, 1.2%) | 33.0% (12.2%, 47.7%) |

Values are presented as median (25 ,75 percentiles).

In multivariable-adjusted restricted cubic spline analyses, increasing proportion of European ancestry among Blacks was associated with higher NT-proBNP concentrations (Figure 2A). Among self-reported Hispanic participants, increasing proportion of European ancestry was also associated with higher NT-proBNP levels, although beyond approximately 60% European ancestry, NT-proBNP levels appeared to plateau (Figure 2B). By contrast, increasing African ancestry appeared to associate with lower NT-proBNP concentrations among both self-reported Blacks and Hispanic individuals (Figure 2, C and D).

Figure 2. Relationships between genetic ancestry and N terminus pro B type natriuretic peptide concentrations in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.

Multivariable-adjusted restricted cubic splines with data presented as point estimate (solid line) and 95% confidence interval (dashed lines). The histograms display the distribution of genetic ancestry within a self-reported race/ethnic group. All analyses adjusted for age, sex, anti-HTN medication, diabetes mellitus, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, estimated glomerular filtration rate, urine albumin to creatinine ratio, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, education, income, left ventricular mass, and left ventricular ejection fraction. Genetic ancestries were included as covariates as follows: Panel A = European, Hispanic, and Chinese; Panels B & D = European, African, and Chinese; Panel C= African, Hispanic, and Chinese.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate racial/ethnic differences in NT-proBNP concentrations that may have a genetic basis. Using data from a large, community-based, multi-ethnic study, we found that NT-proBNP concentrations were lowest among Black and Chinese individuals, intermediate in Hispanics, and highest among White individuals. These differences were independent of other factors previously reported to be associated with NP concentrations, including insulin resistance, obesity, left ventricular mass, ejection fraction, and renal function. Concordantly, we also demonstrated consistent relationships between genetic ancestry and NP concentrations, with greater European ancestry associated with higher NT-proBNP concentrations, and greater African ancestry linked to lower concentrations. These findings not only support the primary result of racial/ethnic differences in NT-proBNP levels, but also support a possible genetic basis. Because NP deficiencies promote hypertension and diabetes mellitus,3–8 our findings raise the possibility that reduced NP activity contributes to racial/ethnic disparities in susceptibility to these as well as related cardiometabolic disorders.

Circulating NP concentrations are lower in individuals with diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance.21–23 These conditions are more common among Black, Chinese, and Hispanic, than White individuals. In this study, even with adjustment for these cardiometabolic comorbidities and hemodynamic factors, NP concentrations were significantly lower in Black, Chinese, and Hispanic compared with White individuals. The magnitude of differences in NT-proBNP concentrations between White individuals and the other racial/ethnic groups (26–43% lower) was similar to that previously reported among obese (6–20% lower) and insulin resistant (10–30% lower) individuals, suggesting the observed racial/ethnic differences in NP concentrations are likely physiologically significant.21,23 Furthermore, in the ARIC study and MESA, it has previously been demonstrated that lower NP concentrations, even within the range that would be considered “normal” or not diagnostic of heart failure and comparable to NT-proBNP concentrations observed in this analysis, are associated with increased risk of diabetes mellitus in follow-up.7,8

Although the precise mechanisms underlying the racial/ethnic differences in NT-proBNP concentrations are incompletely understood, prior studies indicate that a substantial proportion (~40%) of the inter-individual variation in NP concentrations among community-based subjects is attributable to heritable factors.14 Our findings in MESA may provide further support for a genetic contribution to NP concentrations. We observed a “dose-response” relationship between genetic ancestry and NT-proBNP concentrations, such that European ancestry was positively associated with NT-proBNP concentrations, while African ancestry was negatively associated. These contrasting associations suggest multiple variants may influence NP concentrations and these may differ by ancestry.

Prior studies provide some evidence to support a genetic basis for racial/ethnic variation in NP concentrations. For instance, micro-RNA 425 negatively regulates ANP production by binding to a NP precursor A (NPPA) gene variant in the 3’ untranslated region (rs5068 A/G); this variant is more common among White compared with Black individuals and is associated with higher circulating atrial NP concentrations, lower blood pressure, less hypertension, and a favorable metabolic profile.6,10,24,25 By contrast, Blacks are more likely to carry non-synonymous variants in the CORIN gene compared with White individuals.26 Corin is a cardiac serine protease that cleaves NP prohormones into biologically active and inactive components. Individuals with certain CORIN variants are at increased risk for hypertension and ventricular hypertrophy.26,27 Among Chinese individuals, the rs5063 variant in the coding region of NPPA leads to an amino acid change from valine to methionine and is associated with lower blood pressure.28 Genetic variants in the NP clearance receptor (NPR-C) have also been associated with hypertension in Caucasian and Asian individuals.29,30

Although we examined a large, well-phenotyped, multi-ethnic population without prevalent cardiovascular disease, limitations should be noted. Race and ethnicity were self-reported, which may result in misclassification bias; however, our results were similar when NT-proBNP concentrations were examined in relation to genetic ancestry. A small minority of participants had NT-proBNP concentrations below detection limit. However, racial/ethnic differences persisted even when restricted to individuals with detectable NT-proBNP concentrations. The precise mechanisms contributing to racial/ethnic differences in NP concentrations could not be determined; however, the ancestry findings suggest a possible genetic basis. Identifying specific variants that influence NP levels and whose frequencies vary by race or ethnic group is an area for future investigation. In estimating genetic ancestry, there may be misclassification bias due to the inability to account for local ancestry.20 The small proportion of Chinese ancestry among self-reported White, Black, and Hispanic individuals limited power to assess the association between Chinese ancestry and NT-proBNP levels. Despite adjustment for multiple factors that may influence NP concentrations, there may be residual confounding. Finally, in this cross-sectional analysis we cannot define a causal association between low NP concentrations and incident cardiometabolic disease. However, it has previously been demonstrated in both animal and human studies that low NP concentrations are associated with increased risk for diabetes mellitus, and genetic variants in the NP system yielding lower NP concentrations result in hypertension.6–10

In conclusion, NP concentrations varied by race/ethnicity, which appeared to have a genetic basis. Whether augmentation of the NP system is an efficacious strategy for the prevention of cardiometabolic disease among individuals with relatively low NP concentrations warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by contracts N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168 and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by grants UL1-TR-000040 and UL1-TR-001079 from NCRR. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org. This research was also supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants K12 HL109019, 1K23HL128928-01A1, R01-HL-102780, R00-HL-107642, and R01-HL131532; R01-HL134168, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health award numbers UL1TR000445 (Vanderbilt University), the American Heart Association Strategically Focused Research Network grants to Vanderbilt University (14SFRN20420046) and Northwestern University (14SFRN20480260) and an American Heart Association grant to SC. Roche Diagnostics provided reagents for the measurement of NT-proBNP.

Footnotes

Disclosures

DKG, SC, MHC, ASM, JAL, HB, PG, MC, RT, DS, AGB, VC, JCB, and JJC report no relevant disclosures. LBD has received speaking fees from Roche and Critical Diagnostics, and consulting honoraria from Roche Diagnostics and Siemens Healthcare. CdF reports research grants from Roche Diagnostics, Abbot Diagnostics, and Critical Diagnostics, and consulting honoraria from Roche Diagnostics, Siemens Healthcare, Radiometer, Ortho Diagnostics, and Thermo Fisher.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.de Bold AJ, Borenstein HB, Veress AT, Sonnenberg H. A rapid and potent natriuretic response to intravenous injection of atrial myocardial extract in rats. Life Sci. 1981;28:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sengenes C, Berlan M, De Glisezinski I, Lafontan M, Galitzky J. Natriuretic peptides: a new lipolytic pathway in human adipocytes. FASEB J. 2000;14:1345–1351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John SW, Krege JH, Oliver PM, Hagaman JR, Hodgin JB, Pang SC, Flynn TG, Smithies O. Genetic decreases in atrial natriuretic peptide and salt-sensitive hypertension. Science. 1995;267:679–681. doi: 10.1126/science.7839143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birkenfeld AL, Boschmann M, Moro C, Adams F, Heusser K, Franke G, Berlan M, Luft FC, Lafontan M, Jordan J. Lipid mobilization with physiological atrial natriuretic peptide concentrations in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3622–3628. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyashita K, Itoh H, Tsujimoto H, Tamura N, Fukunaga Y, Sone M, Yamahara K, Taura D, Inuzuka M, Sonoyama T, Nakao K. Natriuretic peptides/cGMP/cGMP-dependent protein kinase cascades promote muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and prevent obesity. Diabetes. 2009;58:2880–2892. doi: 10.2337/db09-0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannone V, Boerrigter G, Cataliotti A, Costello-Boerrigter LC, Olson TM, McKie PM, Heublein DM, Lahr BD, Bailey KR, Averna M, Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Burnett JC., Jr A genetic variant of the atrial natriuretic peptide gene is associated with cardiometabolic protection in the general community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazo M, Young JH, Brancati FL, Coresh J, Whelton S, Ndumele CE, Hoogeveen R, Ballantyne CM, Selvin E. NH2-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and risk of diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:3189–3193. doi: 10.2337/db13-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez OA, Duprez DA, Bahrami H, Peralta CA, Daniels LB, Lima JA, Maisel A, Folsom AR, Jacobs DR. Changes in N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and incidence of diabetes: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Diabetes Metab. 2015;41:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meirhaeghe A, Sandhu MS, McCarthy MI, de Groote P, Cottel D, Arveiler D, Ferrieres J, Groves CJ, Hattersley AT, Hitman GA, Walker M, Wareham NJ, Amouyel P. Association between the T-381C polymorphism of the brain natriuretic peptide gene and risk of type 2 diabetes in human populations. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1343–1350. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton-Cheh C, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Levy D, Bloch KD, Surti A, Guiducci C, Kathiresan S, Benjamin EJ, Struck J, Morgenthaler NG, Bergmann A, Blankenberg S, Kee F, Nilsson P, Yin X, Peltonen L, Vartiainen E, Salomaa V, Hirschhorn JN, Melander O, Wang TJ. Association of common variants in NPPA and NPPB with circulating natriuretic peptides and blood pressure. Nat Genet. 2009;41:348–353. doi: 10.1038/ng.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniels LB, Clopton P, Potocki M, Mueller C, McCord J, Richards M, Hartmann O, Anand IS, Wu AH, Nowak R, Peacock WF, Ponikowski P, Mockel M, Hogan C, Filippatos GS, Di Somma S, Ng L, Neath SX, Christenson R, Morgenthaler NG, Anker SD, Maisel AS. Influence of age, race, sex, and body mass index on interpretation of midregional pro atrial natriuretic peptide for the diagnosis of acute heart failure: results from the BACH multinational study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:22–31. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta DK, Claggett B, Wells Q, Cheng S, Li M, Maruthur N, Selvin E, Coresh J, Konety S, Butler KR, Mosley T, Boerwinkle E, Hoogeveen R, Ballantyne CM, Solomon SD. Racial differences in circulating natriuretic peptide levels: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015:4. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.001831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta DK, de Lemos JA, Ayers CR, Berry JD, Wang TJ. Racial Differences in Natriuretic Peptide Levels: The Dallas Heart Study. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Corey D, Leip EP, Vasan RS. Heritability and genetic linkage of plasma natriuretic peptide levels. Circulation. 2003;108:13–16. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000081657.83724.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR, Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O'Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi EY, Bahrami H, Wu CO, Greenland P, Cushman M, Daniels LB, Almeida AL, Yoneyama K, Opdahl A, Jain A, Criqui MH, Siscovick D, Darwin C, Maisel A, Bluemke DA, Lima JA. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, left ventricular mass, and incident heart failure: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:727–734. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.968701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer H, Jacobs DR, Jr, Bild D, Post W, Saad MF, Detrano R, Tracy R, Cooper R, Liu K. Urine albumin excretion and subclinical cardiovascular disease. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2005;46:38–43. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000171189.48911.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Divers J, Redden DT, Rice KM, Vaughan LK, Padilla MA, Allison DB, Bluemke DA, Young HJ, Arnett DK. Comparing self-reported ethnicity to genetic background measures in the context of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) BMC Genet. 2011;12:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manichaikul A, Palmas W, Rodriguez CJ, Peralta CA, Divers J, Guo X, Chen WM, Wong Q, Williams K, Kerr KF, Taylor KD, Tsai MY, Goodarzi MO, Sale MM, Diez-Roux AV, Rich SS, Rotter JI, Mychaleckyj JC. Population structure of Hispanics in the United States: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Leip EP, Wilson PW, Vasan RS. Impact of obesity on plasma natriuretic peptide levels. Circulation. 2004;109:594–600. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112582.16683.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Keyes MJ, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Vasan RS. Association of plasma natriuretic peptide levels with metabolic risk factors in ambulatory individuals. Circulation. 2007;115:1345–1353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan AM, Cheng S, Magnusson M, Larson MG, Newton-Cheh C, McCabe EL, Coviello AD, Florez JC, Fox CS, Levy D, Robins SJ, Arora P, Bhasin S, Lam CS, Vasan RS, Melander O, Wang TJ. Cardiac natriuretic peptides, obesity, and insulin resistance: evidence from two community-based studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3242–3249. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arora P, Wu C, Khan AM, Bloch DB, Davis-Dusenbery BN, Ghorbani A, Spagnolli E, Martinez A, Ryan A, Tainsh LT, Kim S, Rong J, Huan T, Freedman JE, Levy D, Miller KK, Hata A, Del Monte F, Vandenwijngaert S, Swinnen M, Janssens S, Holmes TM, Buys ES, Bloch KD, Newton-Cheh C, Wang TJ. Atrial natriuretic peptide is negatively regulated by microRNA-425. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3378–3382. doi: 10.1172/JCI67383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. [Accessed April 11, 2016];rs5068 S. http://useast.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Variation/Population?db=core;r=1:11845417-11846417;v=rs5068;vdb=variation;vf=4813#population_freq_AFR.

- 26.Dries DL, Victor RG, Rame JE, Cooper RS, Wu X, Zhu X, Leonard D, Ho SI, Wu Q, Post W, Drazner MH. Corin gene minor allele defined by 2 missense mutations is common in blacks and associated with high blood pressure and hypertension. Circulation. 2005;112:2403–2410. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.568881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rame JE, Drazner MH, Post W, Peshock R, Lima J, Cooper RS, Dries DL. Corin I555(P568) allele is associated with enhanced cardiac hypertrophic response to increased systemic afterload. Hypertension. 2007;49:857–864. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000258566.95867.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Mao G, Zhang Y, Tang G, Wen Y, Hong X, Jiang S, Yu Y, Xu X. Association between human atrial natriuretic peptide Val7Met polymorphism and baseline blood pressure, plasma trough irbesartan concentrations, and the antihypertensive efficacy of irbesartan in rural Chinese patients with essential hypertension. Clin Ther. 2005;27:1774–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association S; Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, Bochud M, Johnson AD, Chasman DI, Smith AV, Tobin MD, Verwoert GC, Hwang SJ, Pihur V, Vollenweider P, O'Reilly PF, Amin N, Bragg-Gresham JL, Teumer A, Glazer NL, Launer L, Zhao JH, Aulchenko Y, Heath S, Sober S, Parsa A, Luan J, Arora P, Dehghan A, Zhang F, Lucas G, Hicks AA, Jackson AU, Peden JF, Tanaka T, Wild SH, Rudan I, Igl W, Milaneschi Y, Parker AN, Fava C, Chambers JC, Fox ER, Kumari M, Go MJ, van der Harst P, Kao WH, Sjogren M, Vinay DG, Alexander M, Tabara Y, Shaw-Hawkins S, Whincup PH, Liu Y, Shi G, Kuusisto J, Tayo B, Seielstad M, Sim X, Nguyen KD, Lehtimaki T, Matullo G, Wu Y, Gaunt TR, Onland-Moret NC, Cooper MN, Platou CG, Org E, Hardy R, Dahgam S, Palmen J, Vitart V, Braund PS, Kuznetsova T, Uiterwaal CS, Adeyemo A, Palmas W, Campbell H, Ludwig B, Tomaszewski M, Tzoulaki I, Palmer ND, KidneyGen C, Aspelund T, Garcia M, Chang YP, O'Connell JR, Steinle NI, Grobbee DE, Arking DE, Kardia SL, Morrison AC, Hernandez D, Najjar S, McArdle WL, Hadley D, Brown MJ, Connell JM, Hingorani AD, Day IN, Lawlor DA, Beilby JP, Lawrence RW, Clarke R, Hopewell JC, Ongen H, Dreisbach AW, Li Y, Young JH, Bis JC, Kahonen M, Viikari J, Adair LS, Lee NR, Chen MH, Olden M, Pattaro C, Bolton JA, Kottgen A, Bergmann S, Mooser V, Chaturvedi N, Frayling TM, Islam M, Jafar TH, Erdmann J, Kulkarni SR, Bornstein SR, Grassler J, Groop L, Voight BF, Kettunen J, Howard P, Taylor A, Guarrera S, Ricceri F, Emilsson V, Plump A, Barroso I, Khaw KT, Weder AB, Hunt SC, Sun YV, Bergman RN, Collins FS, Bonnycastle LL, Scott LJ, Stringham HM, Peltonen L, Perola M, Vartiainen E, Brand SM, Staessen JA, Wang TJ, Burton PR, Soler Artigas M, Dong Y, Snieder H, Wang X, Zhu H, Lohman KK, Rudock ME, Heckbert SR, Smith NL, Wiggins KL, Doumatey A, Shriner D, Veldre G, Viigimaa M, Kinra S, Prabhakaran D, Tripathy V, Langefeld CD, Rosengren A, Thelle DS, Corsi AM, Singleton A, Forrester T, Hilton G, McKenzie CA, Salako T, Iwai N, Kita Y, Ogihara T, Ohkubo T, Okamura T, Ueshima H, Umemura S, Eyheramendy S, Meitinger T, Wichmann HE, Cho YS, Kim HL, Lee JY, Scott J, Sehmi JS, Zhang W, Hedblad B, Nilsson P, Smith GD, Wong A, Narisu N, Stancakova A, Raffel LJ, Yao J, Kathiresan S, O'Donnell CJ, Schwartz SM, Ikram MA, Longstreth WT, Jr, Mosley TH, Seshadri S, Shrine NR, Wain LV, Morken MA, Swift AJ, Laitinen J, Prokopenko I, Zitting P, Cooper JA, Humphries SE, Danesh J, Rasheed A, Goel A, Hamsten A, Watkins H, Bakker SJ, van Gilst WH, Janipalli CS, Mani KR, Yajnik CS, Hofman A, Mattace-Raso FU, Oostra BA, Demirkan A, Isaacs A, Rivadeneira F, Lakatta EG, Orru M, Scuteri A, Ala-Korpela M, Kangas AJ, Lyytikainen LP, Soininen P, Tukiainen T, Wurtz P, Ong RT, Dorr M, Kroemer HK, Volker U, Volzke H, Galan P, Hercberg S, Lathrop M, Zelenika D, Deloukas P, Mangino M, Spector TD, Zhai G, Meschia JF, Nalls MA, Sharma P, Terzic J, Kumar MV, Denniff M, Zukowska-Szczechowska E, Wagenknecht LE, Fowkes FG, Charchar FJ, Schwarz PE, Hayward C, Guo X, Rotimi C, Bots ML, Brand E, Samani NJ, Polasek O, Talmud PJ, Nyberg F, Kuh D, Laan M, Hveem K, Palmer LJ, van der Schouw YT, Casas JP, Mohlke KL, Vineis P, Raitakari O, Ganesh SK, Wong TY, Tai ES, Cooper RS, Laakso M, Rao DC, Harris TB, Morris RW, Dominiczak AF, Kivimaki M, Marmot MG, Miki T, Saleheen D, Chandak GR, Coresh J, Navis G, Salomaa V, Han BG, Zhu X, Kooner JS, Melander O, Ridker PM, Bandinelli S, Gyllensten UB, Wright AF, Wilson JF, Ferrucci L, Farrall M, Tuomilehto J, Pramstaller PP, Elosua R, Soranzo N, Sijbrands EJ, Altshuler D, Loos RJ, Shuldiner AR, Gieger C, Meneton P, Uitterlinden AG, Wareham NJ, Gudnason V, Rotter JI, Rettig R, Uda M, Strachan DP, Witteman JC, Hartikainen AL, Beckmann JS, Boerwinkle E, Vasan RS, Boehnke M, Larson MG, Jarvelin MR, Psaty BM, Abecasis GR, Chakravarti A, Elliott P, van Duijn CM, Newton-Cheh C, Levy D, Caulfield MJ, Johnson T consortium CA, Consortium CK, EchoGen c, consortium C-H. Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature. 2011;478:103–109. doi: 10.1038/nature10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kato N, Takeuchi F, Tabara Y, Kelly TN, Go MJ, Sim X, Tay WT, Chen CH, Zhang Y, Yamamoto K, Katsuya T, Yokota M, Kim YJ, Ong RT, Nabika T, Gu D, Chang LC, Kokubo Y, Huang W, Ohnaka K, Yamori Y, Nakashima E, Jaquish CE, Lee JY, Seielstad M, Isono M, Hixson JE, Chen YT, Miki T, Zhou X, Sugiyama T, Jeon JP, Liu JJ, Takayanagi R, Kim SS, Aung T, Sung YJ, Zhang X, Wong TY, Han BG, Kobayashi S, Ogihara T, Zhu D, Iwai N, Wu JY, Teo YY, Tai ES, Cho YS, He J. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies common variants associated with blood pressure variation in east Asians. Nat Genet. 2011;43:531–538. doi: 10.1038/ng.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]