INTRODUCTION

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of adult lymphomas, accounting for approximately 25,000 new cases per year in the United States. Today, the most widely used regimen for the treatment of DLBCL is RCHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). Historically, the CHOP regimen was introduced in the early 1970s. More than 40 years later, the only major therapeutic advancement has been incorporation of the monoclonal antibody rituximab with CHOP, creating the RCHOP regimen. Despite this progress, approximately 50% of patients have disease progression or relapse after RCHOP, and most die of their disease. Accordingly, new treatment modalities are necessary to improve the cure rate of patients with DLBCL.

At the molecular level, DLBCL is a heterogeneous disease. Hence, it is not surprising that many patients do not respond to standard RCHOP therapy. Gene expression profiling studies demonstrated that DLBCL is broadly classified into germinal center B-cell (GCB)-like and activated B-cell (ABC)-like subtypes. Using this “cell of origin” classification, it has been shown that treatment with standard RCHOP regime results in a better cure and overall survival in patients with the GCB subtype when compared with those with the ABC subtype. However, relapses are observed in both subsets after RCHOP therapy, suggesting the existence of additional oncogenic events that mediate resistance to RCHOP, irrespective of the cell of origin. More recent genome sequencing studies revealed a more complex molecular heterogeneity of DLBCL, with genetic alterations frequently observed in GCB and ABC subtypes. Other, less common genetic alterations can preferentially be detected in either GCB or ABC subsets. Novel treatment strategies that are based on lymphoma-associated oncogenic alterations are needed to improve the cure rate of patients with DLBCL.

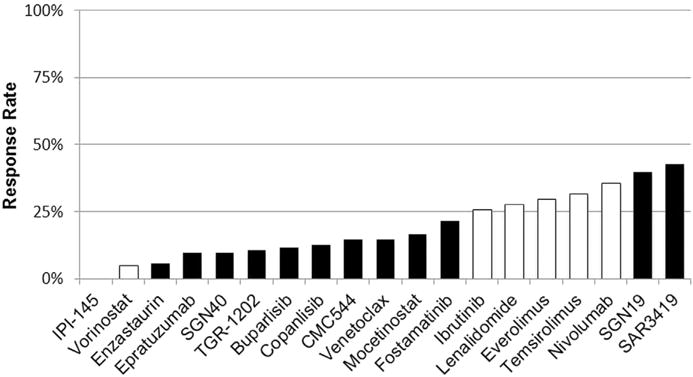

One of the biggest challenges in drug development for patients with cancer, including DLBCL, is the high failure rate caused by excessive toxicity, low response rates, or both (Fig. 1). The success of future drug development in DLBCL depends on using biomarkers to identify patients who are likely to benefit from a specific therapy. The following is a focused review on the most promising agents for the treatment of DLBCL, with a discussion on how to select patients for these novel drugs based on genetic and molecular biomarkers. This article also provides a brief update on recent advances in immune therapy of DLBCL.

Fig. 1.

Single-agent activity in patients with relapsed DLBCL. Results are generated from published data from phase I or phase II studies. Some of these trials are either ongoing and/or enrolled a small number of patients, and therefore these response rates may change with time. Black bars indicate investigational agents with no Food and Drug Administration–approved indication. White bars identify agents with Food and Drug Administration approval for different types of lymphoma, but none are approved for DLBCL.

B-CELL RECEPTOR SIGNALING INHIBITORS

The B-cell receptor (BCR) complex is composed of membrane IgM that is linked with transmembrane heterodimer protein (CD79a/CD79b). Both CD79 proteins contain an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif in their intracellular tails. On BCR crosslinking by an antigen, the CD79a immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif tyrosines (Tyr188 and Tyr199) are phosphorylated, creating a docking site for Src-homology 2 domain-containing kinases, such Lyn, Blk, and Fyn, with subsequent activation of downstream kinases, such as spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and bruton tyrosine kinase (Btk). Aberrant and sustained activation of BCR signaling pathway is implicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of B-cell malignancies, including DLBCL. Novel drugs targeting various components of BCR signaling pathway have been developed, initially targeting SYK, and subsequently targeting BTK.

Spleen Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

SYK is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase important for the development of the lymphatic system. SYK is expressed in cells of the hematopoietic lineage, such as B cells, mast cells, basophils, neutrophils, macrophages, and osteoclasts, but is also present in cells of nonhematopoietic origin, such as epithelial cells, hepatocytes, fibroblasts, neuronal cells, and vascular endothelial cells. Thus, SYK seems to play a general physiologic function in a wide variety of cells. Syk−/− knockout mice die during embryonic development of hemorrhage and show severe defects in the development of the lymphatic system. Fostamatinib disodium (R788), a competitive inhibitor for ATP binding to the Syk catalytic domain, demonstrated a 55% response rate in patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1 Patients with other B-cell malignancies had a lower response rate to fostamatinib. In a recent study, 68 patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL, fostamatinib treatment resulted in a 3% response rate. None of the patients with clinical benefit had ABC genotype.

Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

BTK inactivating mutations impair B-cell development and are associated with the absence of mature B cells and agammaglobulinemia. Ibrutinib is a selective and irreversible inhibitor of BTK. Although ibrutinib demonstrated a significant clinical activity in patients with CLL, mantle cell lymphoma, and Waldenström macroglobulinemia, it has a modest clinical activity in DLBCL and follicular lymphoma. In relapsed DLBCL, ibrutinib treatment resulted in an overall response rate of 23%. In contrast to the results that were observed with the SYK inhibitor fostamatinib, most responses to ibrutinib were observed in patients with the ABC DLBCL subtype.2 This observation generated interest in further investigating ibrutinib in combination with standard chemotherapy regimens for the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed ABC DLBCL.3 A phase 3 randomized trial comparing RCHOP with RCHOP with ibrutinib combination (the Phoenix study) has already completed enrollment of patients with newly diagnosed non-GCB DLBCL, and the results should become available in the near future.

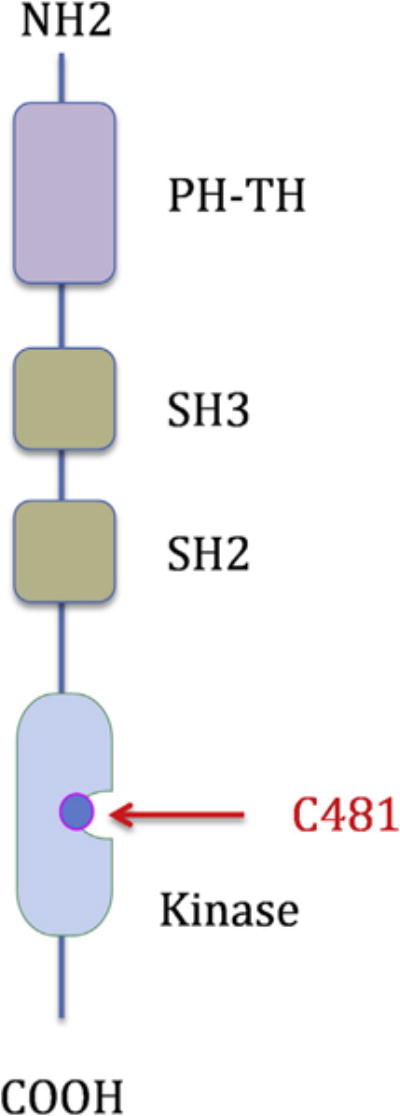

Ibrutinib is generally more tolerated than SYK inhibitors. The most common toxicities are diarrhea and skin rash. Grade 3 to 4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia are seen in less than 10% of patients. Other toxicities include atrial fibrillation and bleeding. Ibrutinib covalently binds to a cysteine 481 (C-481) residue in the BTK kinase domain (Fig. 2). Several other kinases that contain C-481, including members of the TEC family, EGFR, and JAK3, are also inhibited by ibrutinib, which may contribute to its toxicity. To reduce toxicity, several pharmaceutical companies are developing more selective BTK inhibitors. These second-generation, selective, BTK inhibitors, including acalabrutinib and BGB-3111,4,5 also bind to C481. Accordingly, these newer inhibitors are not expected to be more effective than ibrutinib, nor they are expected to work in ibrutinib failures. However, because these selective inhibitors may be more tolerable than ibrutinib, they may be administered without dose interruption or reduction. Whether an uninterrupted treatment schedule will be associated with a more favorable treatment outcome is currently unknown.

Fig. 2.

Schematic structure of bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK). Most small molecule inhibitors, including ibrutinib, bind to the cysteine 481 residue in the kinase domain. PH-TH, pleckstrin homology (PH), TEC homology (TH) domain; SH, SRC homology domain (SH3 followed by SH2).

B-CELL CHRONIC LYMPHOCYTIC LEUKEMIA/LYMPHOMA 2 INHIBITORS

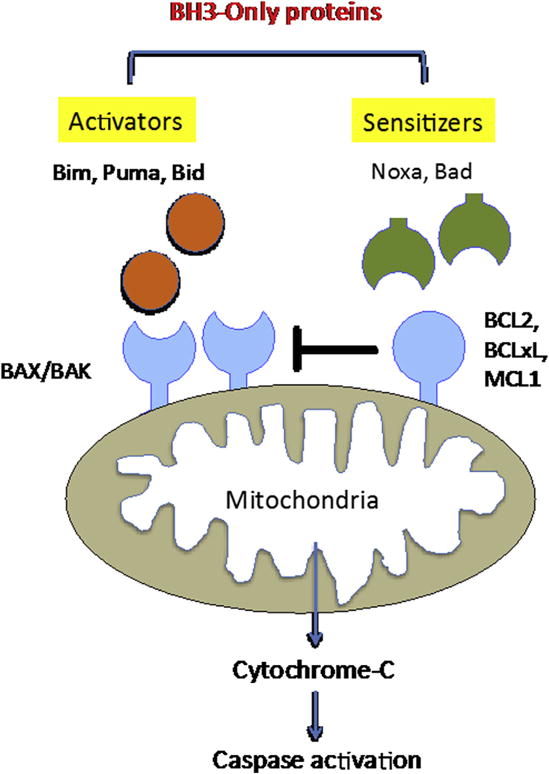

The B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 (BCL2) family of proteins is divided into three functional subgroups: (1) the BCL2-like prosurvival proteins (Bcl2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl1), (2) the proapoptotic BCL2-associated X (BAX)/BCL2-antagonist/killer (BAK) effector proteins, and (3) the proapoptotic BCL2 homology domain 3 (BH3)-only proteins (Fig. 3). The BH3-only proteins are further divided into activating proteins (Bim, Puma, and Bid) and sensitizing proteins (Noxa and Bad). To date, most therapeutic strategies are focused on inhibiting the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members.

Fig. 3.

The Bcl2 family of proteins. The dynamic balance between proapoptotic Bax/Bak and prosurvival Bcl2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl1 is further regulated by activating (Bim, Puma, and Bid) and sensitizing (Noxa and Bad) proteins.

Navitoclax

Navitoclax (ABT-263) is the first-generation, oral, BH3 mimetic that inhibits Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Bcl-w, but not Mcl-1. In a phase I study of 55 patients with relapsed lymphoid malignancies, navitoclax demonstrated no clinical activity in relapsed DLBC. Treatment was associated with dose-dependent thrombocytopenia, which is related to inhibition of Bcl-XL.6–8 Because thrombocytopenia created challenges for future combination strategies, especially with chemotherapy, the development of navitoclax was stopped.

Venetoclax

Venetoclax (ABT-199) is a Bcl-2 selective inhibitor with 100-fold affinity for Bcl2 over Bcl-XL. Consequently, it has a minimal or no effect on platelet counts.9 Similar to navitoclax, venetoclax has no effect on Mcl1. Venetoclax demonstrated remarkable activity in patients with relapsed CLL and mantle cell lymphoma, with response rates exceeding 70%, leading to its initial Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of patients with relapsed CLL carrying p53 genetic alterations.10 However, the response rate in patients with relapsed DLBCL was only 18%.11 Because initial studies were associated with fatal tumor lysis, subsequent studies implemented strict monitoring and treatment of tumor lysis, in addition to a ramped dose schedule over several weeks. Despite the low response rate in relapsed DLBCL, venetoclax-based combination strategies remains of a high interest. Ongoing clinical trials are investigating the efficacy and safety of venetoclax in combination with standard chemotherapy regimens (rituximab plus bendamustine, and RCHOP), and with other small molecule inhibitors.

ENHANCER OF ZESTE HOMOLOG 2 INHIBITORS

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) is a histone-lysine N-methyltransferase enzyme, responsible for methylation of lysine 27 of histone H3 (H3K27). This histone modification is associated with repressed gene transcription when trimethylated (H3K27me3). EZH2 is critical for normal development and EZH2 knockout results in lethality at early stages of mouse development. EZH2-activating mutations or overexpression has been observed in a variety of cancers, including lymphoma.12–14 Wild-type and mutant EZH2 functions are essential for GCB-type DLBCLs but not for ABC DLBCLs, suggesting that EZH2 inhibitors should primarily be effective in GCB-type DLBCLs. Preclinical experiments demonstrated the potential therapeutic value of EZH2 inhibitors in lymphoma.15,16 In a phase I study, the oral EZH2 inhibitor, tazemetostat, was evaluated in 45 patients, including 19 with relapsed lymphoma. Responses were observed in 9 of 15 evaluable patients, including those with wild-type EZH2.17 A phase II study is currently enrolling patients to further confirm the clinical activity in patients with DLBCL. The study will enroll ABC and GCB subtypes to confirm whether there is preferential activity in a specific DLBCL subtype.

IMMUNE CHECKPOINT INHIBITORS

The immune system is physiologically regulated by a set of cell surface proteins to downregulate T-cell activation to maintain self-tolerance and prevent autoimmunity.18 This process is frequently hijacked by tumor cells to enable them to evade T-cell mediated antitumor immunity. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4/CD152 (CTLA-4), is an immune checkpoint protein that is expressed on the surface of T cells. The ligands for CTLA-4 are CD80 or CD86, which are typically expressed by antigen-presenting cells. Engagement of CTAL-4 with its ligands results in T-cell inactivation. Another checkpoint system involves the engagement between programmed death-1 (PD-1), which is expressed by T cells, and its ligands (PDL-1 and PDL-2). CTLA-4 knockout mice succumb to a lethal multiorgan lymphoproliferative disease, whereas inactivating PD-1, and its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2, result in a milder phenotype that is associated with late-onset organ-specific inflammation.19,20

CTLA-4 and PD-1 are currently being targeted for the treatment of cancer, including lymphoma. Earlier studies with the anti-CTLA-4 antibody, ipilimumab, produced modest clinical activity in patients with relapsed B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma.21 More recently, trials using blocking antibodies to PD-1 showed a more promising clinical activity in patients with relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma.22–24 The experience in patients with relapsed DLBCL remains limited to a small number of patients treated in a phase I study, demonstrating a 40% response rate. Other studies are currently evaluating the efficacy of various antibodies targeting PD-L1, such as MPDL3280A, but the results are still pending.

CHIMERIC ANTIGEN RECEPTOR T CELLS

Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) are composed of a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from a murine or humanized antibody that redirects T cells to a specific antigen that is expressed by tumor cells. In B-cell lymphoma, CARs have been typically directed to CD19.25 CAR T cells can recognize and kill tumor cells in an HLA-independent manner. Several CAR T-cell platforms are currently in clinical trials, with no clear superiority of one platform over the other.26 Although clinical results were achieved in patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia,27 results in patients with B-cell lymphoma were more modest. Future directions will focus on further enhancing T-cell activation, including combination strategies with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Adverse events associated with CAR T-cell therapy include cytokine release syndrome, encephalopathy, and B-cell aplasia. Cytokine release syndrome includes fever, tachycardia, hypotension, capillary leak syndrome, and respiratory distress.28,29 Encephalopathy may manifest as mild confusion to obtundation, aphasia, and seizures.30 B-cell aplasia has been noted in CAR T-cell therapy caused by depletion of nonmalignant CD19 B lymphocytes.27,30,31

SUMMARY

Patients with relapsed DLBCL who are not candidates for stem cell transplant, or whose disease relapses after stem cell transplant, have clear unmet medical needs and are candidates for drug development. Although, there are currently no agents approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of relapsed DLBCL, the landscape of new agents is promising. Future direction should focus on the development of mechanism-based combination regimens, and biomarker-driven patients’ selection.

KEY POINTS.

DLBCL is the most common type of lymphoma in the western world.

No single agent has been approved for the treatment of DLBCL in more than a decade.

Agents targeting B-cell receptor signaling, Bcl2 protein, and PD1 immune checkpoint, have modest single-agent activity in relapsed DLBCL.

References

- 1.Friedberg JW, Sharman J, Sweetenham J, et al. Inhibition of Syk with fostamatinib disodium has significant clinical activity in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:2578–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson WH, Young RM, Schmitz R, et al. Targeting B cell receptor signaling with ibrutinib in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Nat Med. 2015;21:922–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Younes A, Thieblemont C, Morschhauser F, et al. Combination of ibrutinib with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) for treatment-naive patients with CD20-positive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a non-randomised, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1019–26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrd JC, Harrington B, O’Brien S, et al. Acalabrutinib (ACP-196) in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):323–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tam C, Grigg AP, Opat S, et al. The BTK inhibitor, Bgb-3111, is safe, tolerable, and highly active in patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies: initial report of a phase 1 first-in-human trial. Blood. 2015;126:832. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davids MS, Letai A. ABT-199: taking dead aim at BCL-2. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:139–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts AW, Advani RH, Kahl BS, et al. Phase 1 study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antitumour activity of the BCL2 inhibitor navitoclax in combination with rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory CD201 lymphoid malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2015;170:669–78. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson WH, O’Connor OA, Czuczman MS, et al. Navitoclax, a targeted high-affinity inhibitor of BCL-2, in lymphoid malignancies: a phase 1 dose-escalation study of safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and antitumour activity. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1149–59. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70261-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Souers AJ, Leverson JD, Boghaert ER, et al. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat Med. 2013;19:202–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):311–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerecitano JF, Roberts AW, Seymour JF, et al. A phase 1 study of venetoclax (ABT-199/GDC-0199) monotherapy in patients with relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2015;126:254. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morin RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, et al. Somatic mutations altering EZH2 (Tyr641) in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of germinal-center origin. Nat Genet. 2010;42:181–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beguelin W, Popovic R, Teater M, et al. EZH2 is required for germinal center formation and somatic EZH2 mutations promote lymphoid transformation. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:677–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velichutina I, Shaknovich R, Geng H, et al. EZH2-mediated epigenetic silencing in germinal center B cells contributes to proliferation and lymphomagenesis. Blood. 2010;116:5247–55. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-280149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qi W, Chan H, Teng L, et al. Selective inhibition of Ezh2 by a small molecule inhibitor blocks tumor cells proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:21360–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210371110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCabe MT, Ott HM, Ganji G, et al. EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2-activating mutations. Nature. 2012;492:108–12. doi: 10.1038/nature11606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ribrag V, Soria J-C, Michot J-M, et al. Phase 1 study of tazemetostat (EPZ-6438), an inhibitor of enhancer of zeste-homolog 2 (EZH2): preliminary safety and activity in relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) patients. Blood. 2015;126:473. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in CTLA-4. Science. 1995;270:985–8. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, et al. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lym-phoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3:541–7. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ansell SM, Hurvitz SA, Koenig PA, et al. Phase I study of ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody, in patients with relapsed and refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6446–53. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:311–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armand P, Shipp MA, Ribrag V, et al. PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma after brentuximab vedotin failure: safety, efficacy, and biomarker assessment. Blood. 2015;126:584. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zinzani PL, Ribrag V, Moskowitz CH, et al. Phase 1b study of PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab in patients with relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) Blood. 2015;126:3986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadelain M. CAR therapy: the CD19 paradigm. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3392–400. doi: 10.1172/JCI80010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramos CA, Heslop HE, Brenner MK. CAR-T cell therapy for lymphoma. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:165–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051914-021702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brentjens RJ, Davila ML, Riviere I, et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:177ra38. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maude SL, Barrett D, Teachey DT, et al. Managing cytokine release syndrome associated with novel T cell-engaging therapies. Cancer J. 2014;20:119–22. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee DW, Gardner R, Porter DL, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood. 2014;124:188–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-552729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9967):517–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grupp SA, Kalos M, Barrett D, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified Tcells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1509–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]