Abstract

Our objective was to determine the significance of age in patients treated with sequential or concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (LA-NSCLC). Ninety-eight patients were 70 years of age or younger and 25 were older than 70 years. In multivariable analysis, there was no difference in the progression-free survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.15; P = .64) or overall survival (HR, 1.18; P = .65) of older versus younger patients. Chemoradiotherapy is an effective treatment in elderly patients with LA-NSCLC, with outcomes similar to that in younger patients.

Background

The objective of this study was to review our institution’s experience among patients with locally advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (LA-NSCLC) treated with chemotherapy and radiation and to determine the prognostic significance of age.

Patients and Methods

Patients were included if they underwent sequential or concurrent chemoradiotherapy from 2006 to 2014 for LA-NSCLC. Patients were stratified according to age ≤70 and >70 years. Kaplan–Meier and Cox regression methods were performed to evaluate overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS).

Results

One hundred twenty-three patients were identified. Ninety-eight patients were 70 years of age or younger and 25 patients were older than 70 years of age. The median radiotherapy dose was 6660 cGy (range, 3780–7600 cGy). A greater percentage of elderly patients were men, 72% (18 patients) versus 39% (38 patients) (P = .006) and received carboplatin/paclitaxel-based chemotherapy, 60% (15 patients) versus 21% (20 patients) (P < .001). Median follow-up for OS was 25.9 (95% confidence interval [CI], 21.3–33.9) months. There was no difference in the PFS of older patients versus younger patients (hazard ratio [HR], 1.15; P = .64), adjusted for significant covariates. The 1-year PFS rate for patients 70 years of age or younger was 51% (95% CI, 42%–63%) versus 45% (95% CI, 28%–71%) in patients older than 70 years. After adjusting for significant covariates, there was no difference in the OS of older patients compared with younger patients (HR, 1.18; P = .65). The 1-year OS rate for patients 70 years of age or younger was 77% (95% CI, 68%–86%) versus 56% (95% CI, 39%–81%) in patients younger than 70 years.

Conclusion

Chemoradiotherapy is an effective treatment in elderly patients with LA-NSCLC, with outcomes similar to that in younger patients. Appropriately selected elderly patients should be considered for chemoradiation.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Radiation, Geriatric, Oncology, Retrospective study

Introduction

In the United States, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death and the second most common cancer in men and women. It is estimated that there will be 224,390 new cases of lung and bronchus carcinoma and 158,080 deaths from this cancer in 2016.1 The most rapidly growing population in the United States are those aged 65 years and older.2 By 2050, this age group is expected to reach 88.5 million, making up 20.2% of the population.3 Because of the increasing growth and aging of the population, as well as the prevalence of risk factors such as smoking, obesity, and sedentary lifestyles, the incidence of malignancy is increasing.4 Increasing age is directly associated with increasing rates of cancer, corresponding to an 11-fold higher incidence of cancer in persons older than the age of 65 years compared with those younger than 65 years of age.5 In an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, nearly half of lung cancer cases are diagnosed in people aged older than 70 years, and 14% of cases are diagnosed in patients older than 80 years of age.6

Cancer represents a significant health problem at any age, and the disease and treatments offered can affect a patient’s health and quality of life. With advancing age, patients have physiologic changes resulting in reduced hepatic and renal function, increased body fat, reduced total body water, as well as added comorbidities, and decreasing social support, which might lead to decreased survival.7–9 The diagnosis of lung cancer in an elderly patient with the normal and pathologic changes associated with aging might introduce great complexity into the clinical decision-making process and create a difficult situation for health care providers.5 The risk of toxicity from aggressive cancer therapy must therefore be carefully balanced against the potential benefit in this population. Physicians must also be aware of the risk that elderly patients might be undertreated or not treated altogether, solely because of their age, despite being otherwise fit for appropriate therapy.10,11

Locally advanced (LA) non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is commonly managed with multimodal therapy consisting of chemotherapy and radiation,12,13 yet there are limited data regarding the efficacy and safety of this approach in elderly patients.14 We therefore sought to review our institution’s experience among patients with LA-NSCLC treated with chemotherapy and radiation and to determine the prognostic significance of age.

Patients and Methods

After institutional review board approval, a retrospective study of patients treated from 2006 to 2014 for LA-NSCLC with radiation and chemotherapy was performed. Patients were included if they had biopsy-proven LA-NSCLC, defined as stages IIB to IIIB, and underwent either sequential or concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Medical records were reviewed to obtain demographic, clinical, radiographic, and pathologic data. Diagnosis was established using a bronchoscopic or computed tomography (CT)-guided biopsy and staging studies routinely included a CT scan of the thorax and abdomen, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, and an 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scan. Staging was assigned on the basis of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, seventh edition.15 Clinical radiation pneumonitis included patients with Grade ≥2 pneumonitis, defined according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0.16

All patients included in this analysis underwent a course of sequential or concurrent chemoradiotherapy. This course of therapy was determined by the treating physicians, generally after evaluation and discussion in a multidisciplinary tumor conference in which pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, and pathologists were present. The choice of chemotherapeutic regimens, and any modifications that might have been made throughout the course of treatment, was determined by the managing medical oncologist. The dose, modality, and technique of radiation therapy were decided by the managing radiation oncologist. For most cases, a 4-dimensional CT (4DCT) scan was typically performed at the time of simulation for assessment of tumor motion. The gross tumor volume (GTV) included the primary lung tumor and involved lymph nodes on the basis of CT and positron emission tomography imaging. The internal target volume (ITV) included GTV contoured on all 10 phases of 4DCT imaging. The ITV was typically expanded by 5 mm to generate the clinical target volume (CTV). The CTV was expanded by an additional 5 mm to generate the planning target volume (PTV) in patients for whom daily imaging was performed. In patients in whom daily imaging was not performed, a larger PTV expansion was typically used. Radiation was delivered with either a 3-D conformal technique, intensity modulated radiation therapy, or a combination of the 2 techniques. Most patients were treated to a total dose of 60 to 70 Gy in 1.8- to 2.0-Gy daily fractions. During radiotherapy, patients were evaluated at least weekly in on-treatment clinic to assess progress, manage adverse effects of treatment, and to determine whether or not a break in treatment was necessary.

Patients were stratified according to age 70 years of age or younger and age older than 70 years. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to describe the data and Cox regression was performed to compare the overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) of the 2 patient groups. Analyses were stratified according to treatment regimen received (taxane-based or nontaxane-based) to mitigate concerns about comparing survival curves in a retrospective sample. Statistically significant covariates, including age, disease stage, chemotherapy regimen and sequence, total radiation dose, and lung dosimetrics were included in the separate Cox regression models for PFS and OS.

Results

One hundred twenty-three patients were identified. The median age was 61 (range, 40–90) years for the entire cohort; 98 patients were 70 years of age or younger (median age, 59.0), whereas 25 patients were older than 70 years of age (median age, 77.7 years). In patients older than 70 years, 6 were aged 71 to 75 years and 19 were older than 75 years. Five patients were included with stage IIB, 79 with IIIA, and 39 with stage IIIB disease. The median radiotherapy dose was 6660 cGy (range, 3780–7600 cGy). Chemotherapy regimens consisted of cisplatin/etoposide (n = 54), carboplatin/paclitaxel (n = 35), carboplatin/pemetrexed (n = 30), gemcitabine (n = 3), and erlotinib (n = 1). Table 1 shows the patient characteristics in the 2 groups.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Variable | ≤70 Years Old (n = 98) | >70 Years Old (n = 25) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male Sex | 38 (39) | 18 (72) | .006 |

| Race | .411 | ||

| African-American | 54 (55) | 11 (44) | |

| Caucasian | 40 (41) | 12 (48) | |

| Other | 4 (4) | 2 (8) | |

| Stage | .084 | ||

| IIB | 3 (3) | 2 (8) | |

| IIIA | 60 (61) | 19 (76) | |

| IIIB | 35 (36) | 4 (16) | |

| Histology | .481 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 44 (45) | 14 (56) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 39 (40) | 11 (44) | |

| Undifferentiated NSCLC | 12 (12) | 0 (0) | |

| Large cell carcinoma | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Smoker | 95 (97) | 22 (88) | .098 |

| COPD | 34 (35) | 7 (28) | .692 |

Data are presented as n (%) except where otherwise stated.

Abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSCLC = non–small-cell lung cancer.

For patients 70 years of age and younger, 25 received sequential treatment (25%), 35 received neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiation (36%), and 38 received concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone (39%). For patients older than 70 years of age, 9 received sequential treatment (36%), 6 received neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiation (24%), and 10 received concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone (40%). Table 2 shows the treatment characteristics of the 2 groups. A higher percentage of elderly patients were men, 72% versus 39% (P = .006) and received taxane-based chemotherapy; 60% versus 21% (P < .001).

Table 2.

Treatment Characteristics

| Variable | ≤70 Years Old (n = 98) | >70 Years Old (n = 25) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy Sequence | .426 | ||

| Sequential therapy | 25 (26) | 9 (36) | |

| Concurrent CRT | 73 (74) | 16 (64) | |

| Taxane-Based Chemotherapy | 45 (46) | 18 (72) | .035 |

| Chemotherapy Regimens | – | ||

| Cisplatin/etoposide | 51 (52) | 3 (12) | |

| Carboplatin/paclitaxel | 20 (21) | 15 (60) | |

| Carboplatin/pemetrexed | 24 (24) | 6 (24) | |

| Gemcitabine | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Erlotinib | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | |

| Median Radiation Dose | 6660 cGy | 6660 cGy | – |

Data are presented as n (%) except where otherwise stated.

Abbreviation: CRT = chemoradiotherapy.

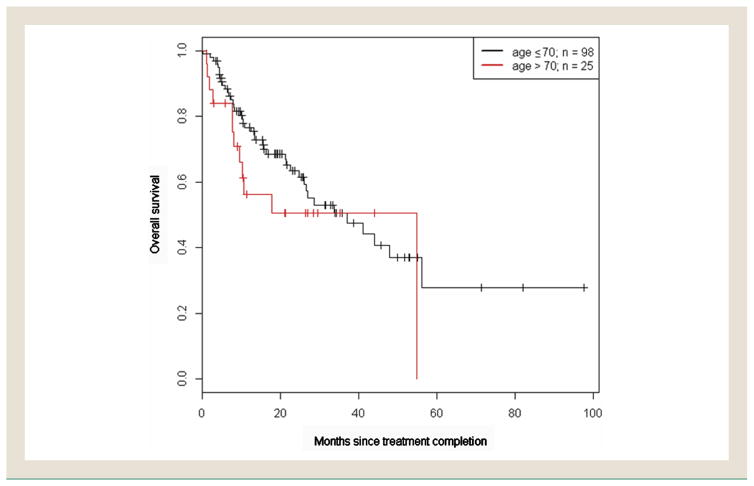

Median follow-up for OS was 25.9 (95% confidence interval [CI], 21.3–33.9) months. The median OS for patients 70 years of age and younger and those older than 70 years was 37.1 (95% CI, 26.0-not reached [NR]) months and 54.8 (95% CI, 9.5-NR) months, respectively. There was no difference in the OS of older patients versus younger patients (hazard ratio [HR], 1.18; P = .65), adjusted for the volume of lung receiving at least 10 Gy (lung V10) and stratified according to treatment received (Figure 1). The 1-year OS rate for patients 70 years of age or younger was 77% (95% CI, 68%–86%) versus 56% (95% CI, 39%–81%) in patients older than 70 years. There was no difference in the PFS of older patients versus younger patients (HR, 1.15; P = .64), adjusted for tumor location and lung V5 and stratified according to treatment received (Figure 2). The 1-year PFS rate for patients 70 years of age and younger was 51% (95% CI, 42%–63%) versus 45% (95% CI, 28%–71%) in patients older than 70 years. The median PFS for patients 70 years of age and younger and those older than 70 years was 13.0 (95% CI, 9.9–23.6) months and 8.7 (95% CI, 7.3-NR) months, respectively.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier Curve of Overall Survival in Patients Aged 70 Years and Younger Versus Those Aged Younger than 70 Years (P = .65)

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier Curve of Progression-Free Survival (PFS) in Patients Aged 70 Years and Younger Versus Those Aged Younger than 70 Years (P = .64)

The rate of symptomatic pneumonitis was nonsignificantly higher in the elderly group; 10 of 25 patients (40%) versus 23 of 98 patients (23%) in the younger cohort (P = .158). For the entire population, there was no difference in pneumonitis on the basis of chemotherapy regimens. The mean total lung V5, V20, and mean lung dose (MLD) did not differ significantly on the basis of age. The V5, V20, and MLD were 41.5%, 27.4%, and 16.3%, respectively, for patients 70 years of age and younger, and 41.0%, 25.0%, and 15.5%, respectively, for patients older than 70 years.

Discussion

As life expectancy continues to lengthen and the elderly proportion of the population grows, the incidence of cancer is increasing.17 Despite this, data for the most appropriate treatment of this cohort of patients are lacking, because elderly patients are generally underrepresented in clinical trials for NSCLC.18–21 Because treatment recommendations are on the basis of data from clinical trials that largely enroll younger patients, it is unknown whether it is appropriate to generalize these data to elderly patients. Additionally, it has been shown that elderly patients are less likely to be referred to medical oncology or receive chemotherapy22 despite evidence from a prospective randomized controlled trial that showed improved survival for elderly patients who receive chemotherapy compared with best supportive care.23 Additional data are essential to better understand how elderly patients with LA-NSCLC respond to combined modality therapy. The present study adds data to the scarce existing body of literature regarding a common and often fatal malignancy, which is certain to become a growing problem in the aging population.

Several studies have investigated outcomes among elderly patients who receive chemotherapy and radiation for LA-NSCLC. In a combined analysis of 6 prospective Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) trials,24 it was reported that patients 70 years of age or younger had improved survival with more aggressive therapy, and patients older than 70 years achieved the best quality-adjusted survival time with standard radiotherapy alone. In this trial, quality-adjusted survival time was calculated by weighting the time spent with a specific toxicity, as well as local or distant tumor progression. Furthermore, each toxicity was weighted with increasing severity as the toxicity increased in grade. In the present study, an increase in clinical radiation pneumonitis was observed in the elderly group without a statistically significant difference in survival. When taking into account the disparate rates of pneumonitis between the 2 groups, the results of our study might actually be concordant with the combined RTOG analysis.

Our findings are consistent with a secondary analysis of a phase III trial of the North Central Cancer Treatment Group,25 which examined chemotherapy with either twice per day radiation therapy or daily radiation in patients with stage III NSCLC. In this analysis, it was reported that, despite a higher rate of toxicity (myelosuppression and pneumonitis), elderly patients were found to have survival rates that were equivalent to that of younger patients. From these data, the authors concluded that fit elderly patients with LA-NSCLC should be encouraged to receive combined modality therapy, preferably in a clinical trial, with careful monitoring.

In an attempt to provide evidence-based recommendations for the management of elderly patients with NSCLC, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Elderly Task Force and Lung Cancer Group, in collaboration with the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG), developed an expert panel resulting in a consensus article for the management of this patient population.26 For LA-NSCLC, they advise cautious interpretation of the limited data and that treatment decisions should consider a patient’s life expectancy, comorbidities, functional status, and preferences. They also note that chemoradiation, either sequentially or concurrently, should be considered as an option in select, fit, elderly patients.

Additionally, in a recent meeting of an expert panel in Italy, a set of recommendations was issued using the best available data regarding the management of elderly patients with LA-NSCLC. The panelists agreed that elderly patients should not be excluded from combined modality chemoradiation therapy because of age alone and that fit elderly patients might benefit from concurrent treatment. They also concluded that elderly patients who are ineligible for concurrent chemoradiotherapy might be considered for sequential treatment because of the prospect of less toxicity compared with concurrent therapy.27

The decision for treatment requires understanding of biological and cancer-related factors in the context of the patient’s overall condition, including quality of life, and performance status, in addition to the availability of effective treatment options. Furthermore, another important element of caring for the elderly is a discussion regarding the goals of care (cure, prolongation of life, or palliation of symptoms), as well as understanding the patient’s inclination to pursue aggressive therapy. Chronologic age alone is not a reliable predictor of life expectancy or risk of treatment-related toxicity.17,28 Therefore, effective management of LA-NSCLC requires a practitioner to be skilled in the overall evaluation of geriatric patients. Currently, there are many ways to assess overall health in the elderly population.29

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for Older Adult Oncology include a useful algorithm regarding the approach to decision-making in the older adult cancer patient.30 This includes evaluating whether or not a patient is likely to die or suffer from malignancy compared with life expectancy, has decision-making capacity, and whether or not a patient’s goals and values are consistent with wanting anticancer therapy. After this initial assessment, risk factors for adverse outcomes from cancer treatment are examined. This is the basis of an essential framework for choosing which and what type of therapy should be used.

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is a multidimensional, interdisciplinary diagnostic process used to determine a geriatric patient’s medical, psychosocial, and functional capabilities and is used to develop a coordinated and integrated plan for treatment and long-term follow-up.31 It includes the assessment of several domains such as functionality, mobility/risk of falls, cognition, depression, comorbidity, polypharmacy, social situation, and geriatric syndromes.29 CGA has been shown to be a valuable tool in geriatric medicine. Although there are no prospective randomized trials showing a survival or quality of life benefit for CGA use in cancer patients, there are mounting data that CGA will be useful in the practice of oncology. A review of studies using geriatric assessment in the setting of lung cancer32 reported a high prevalence of geriatric impairments despite good Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status scores. Components of the geriatric assessment, including objective physical capacity and nutritional status, were consistently associated with mortality. Additionally, the SIOG endorses the importance of CGA for detection of impairments not identified in routine history or physical examination, ability to predict severe treatment-related toxicities, ability to predict OS in a variety of tumors and treatment settings, and ability to influence treatment choice and intensity.31 Use of a geriatric assessment tool might allow better selection of elderly patients who are fit for combined modality therapy for LA-NSCLC.

The limitations of our study include those that are inherent to all retrospective series. The sample size in this study was relatively small, which limits the ability to perform extensive statistical analyses. Treatment was nonstandardized and thus there is the potential for selection bias, illustrated by the fact that significantly more patients in the elderly cohort received taxane-based chemotherapy. Despite the variation in chemotherapy, after adjusting for age, we found no significant differences in pneumonitis or OS on the basis of the chemotherapy regimen. Also, because of the retrospective nature of this review and the difficulty in reliably determining patients’ performance status at the time of treatment initiation, we concluded that it would be imprudent to report this information. As such we were unable to account for potential variations of performance status between the 2 cohorts. Finally, some toxicities inherent to treatment, such as esophagitis, were inconsistently recorded and thus not reportable in our study.

Conclusion

Chemoradiotherapy is an effective treatment in elderly patients with LA-NSCLC, with outcomes similar to that in younger patients. Appropriately selected elderly patients should be considered for definitive management with chemotherapy and radiation.

Clinical Practice Points.

As life expectancy continues to lengthen and the elderly proportion of the population grows, the incidence of cancer is increasing.

Locally advanced NSCLC is commonly managed with multimodal therapy consisting of chemotherapy and radiation, yet there are limited data regarding the efficacy and safety of this approach in elderly patients.

The present study adds data to the scarce existing body of literature regarding a common and often fatal malignancy, which is certain to become a growing problem in the aging population.

We reviewed our institution’s experience among patients with LA-NSCLC treated with either sequential or concurrent chemotherapy and radiation and to determine the prognostic significance of age.

In our cohort, 98 patients were 70 years of age or younger and 25 were older than 70 years of age. In multivariable analysis, there was no difference in the PFS (HR, 1.15; P = .64) or OS (HR, 1.18; P = .65) of older versus younger patients.

Pertinent literature and methods of geriatric assessment that might help a clinician determine optimal treatment options are also discussed in this report.

Chemoradiotherapy is an effective treatment in elderly patients with LA-NSCLC, with outcomes similar to that in younger patients.

Appropriately selected elderly patients should be considered for definitive management with chemotherapy and radiation.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have stated that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werner CA. 2010 Census Briefs. The Older Population: 2010: U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration. Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halaweish I, Alam HB. Changing demographics of the American population. Surg Clin North Am. 2015;95:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yancik R. Cancer burden in the aged: an epidemiologic and demographic overview. Cancer. 1997;80:1273–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owonikoko TK, Ragin CC, Belani CP, et al. Lung cancer in elderly patients: an analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5570–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLean AJ, Le Couteur DG. Aging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:163–84. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffe S, Balducci L. Cancer and age: general considerations. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichtman SM. Guidelines for the treatment of elderly cancer patients. Cancer Control. 2003;10:445–53. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang S, Wong ML, Hamilton N, Davoren JB, Jahan TM, Walter LC. Impact of age and comorbidity on non–small-cell lung cancer treatment in older veterans. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1447–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidoff AJ, Gardner JF, Seal B, Edelman MJ. Population-based estimates of survival benefit associated with combined modality therapy in elderly patients with locally advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:934–41. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820eed00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodrigues G, Choy H, Bradley J, et al. Definitive radiation therapy in locally advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: executive summary of an American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Akerley W, et al. Non–small-cell lung cancer, version 1. 2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:1738–61. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bayman N, Alam N, Faivre-Finn C. Radiotherapy for lung cancer in the elderly. Lung Cancer. 2010;68:129–36. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4. 0. NIH Publication # 09-7473. Department of Health and Human Services, National Cancer Institute; Washington DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pallis AG, Fortpied C, Wedding U, et al. EORTC elderly task force position paper: approach to the older cancer patient. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1502–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Jr, Albain KS. Under-representation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:2061–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennens RR, Giles GG, Fox RM. Increasing underrepresentation of elderly patients with advanced colorectal or non–small-cell lung cancer in chemotherapy trials. Intern Med J. 2006;36:216–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yee KW, Pater JL, Pho L, Zee B, Siu LL. Enrollment of older patients in cancer treatment trials in Canada: why is age a barrier? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1618–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacher AG, Le LW, Leighl NB, Coate LE. Elderly patients with advanced NSCLC in phase III clinical trials: are the elderly excluded from practice-changing trials in advanced NSCLC? J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:366–8. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827e2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawe DE, Pond GR, Ellis PM. Assessment of referral and chemotherapy treatment patterns for elderly patients with non–small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2016 Jun 8; doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.05.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2016.05.012.2016, Published online. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gridelli C. The ELVIS trial: a phase III study of single-agent vinorelbine as first-line treatment in elderly patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study. Oncologist. 2001;6(suppl 1):4–7. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-suppl_1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Movsas B, Scott C, Sause W, et al. The benefit of treatment intensification is age and histology-dependent in patients with locally advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a quality-adjusted survival analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) chemoradiation studies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:1143–9. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schild SE, Stella PJ, Geyer SM, et al. The outcome of combined-modality therapy for stage III non–small-cell lung cancer in the elderly. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3201–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pallis AG, Gridelli C, Wedding U, et al. Management of elderly patients with NSCLC; updated expert’s opinion paper: EORTC Elderly Task Force, Lung Cancer Group and International Society for Geriatric Oncology. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1270–83. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gridelli C, Balducci L, Ciardiello F, et al. Treatment of elderly patients with non–small-cell lung cancer: results of an international expert panel meeting of the Italian Association of Thoracic Oncology. Clin Lung Cancer. 2015;16:325–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wedding U, Honecker F, Bokemeyer C, Pientka L, Hoffken K. Tolerance to chemotherapy in elderly patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2007;14:44–56. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pallis AG, Wedding U, Lacombe D, Soubeyran P, Wildiers H. Questionnaires and instruments for a multidimensional assessment of the older cancer patient: what clinicians need to know? Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1019–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. [Accessed: September 9, 2015];Older Adult Oncology (Version 2. 2015) Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/senior.pdf.

- 31.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2595–603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulkes KJ, Hamaker ME, van den Bos F, van Elden LJ. Relevance of a geriatric assessment for elderly patients with lung cancer-a systematic review. Clin Lung Cancer. 2016 Jun 2; doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.05.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2016.05.007, Published online. [DOI] [PubMed]