Abstract

Introduction

Infectious complications after FEVAR cause significant problems, with radical surgery considered to be the last resort for treatment.

Case report

A 72 year old man presented with infection 1 month after FEVAR. Conservative therapy with percutaneous abscess drainage and antibiotics suppressed the infection for 10 months; however, when new peri-aortic abscesses developed, the patient agreed to revision surgery. The endograft was explanted and an autologous in situ venous reconstruction was performed. As a result of post-operative complications, the patient died 3 days later.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that autologous venous reconstruction is technically feasible. An earlier decision on such radical surgery could potentially have improved the patient's chances of survival.

Keywords: Fenestrated endovascular aneurysm repair (FEVAR), Infection, Autologous reconstruction

Highlights

-

•

Infection of a fenestrated abdominal endograft causes a major problem with high morbidity and mortality rates.

-

•

Explantation of the endograft with autologous venous reconstruction is technically feasible.

-

•

Earlier decision for radical surgery could potentially improve survival rates.

Introduction

Infection is a rare but devastating complication after endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) with a reported incidence of less than 1%.1, 2 Fenestrated endovascular aneurysm repair (FEVAR) is an endovascular alternative for repair of thoraco-abdominal and juxtarenal aortic aneurysms.3 There is no literature on infected fenestrated endografts. But the growing number of such procedures means more of these challenging cases are expected.

The case of a 72 year old man with a fenestrated endograft infection, which was managed surgically, is presented.

Case Report

A 72 year old man with a medical history of COPD Gold C and hyperlipidemia underwent a three vessel FEVAR for an asymptomatic thoraco-abdominal aneurysm 64 mm in diameter. The immediate post-operative course was favourable. One month post-operatively he was re-admitted with a Klebsiella pneumoniae urinary infection, which was treated with IV antibiotics. A CT scan for ongoing fever showed infection of the endograft with multiple intra-abdominal abscesses. The largest abscess was drained percutaneously and antibiotic therapy guided by the antibiogram of cultures stabilised the patient. The patient refused surgery at that time. After 2 months the patient was discharged with lifelong oral antibiotics. During the next 8 months the patient was re-admitted four times with back pain and malaise. CT imaging showed a stable peri-aortic inflammatory cuff and stable residual small collections.

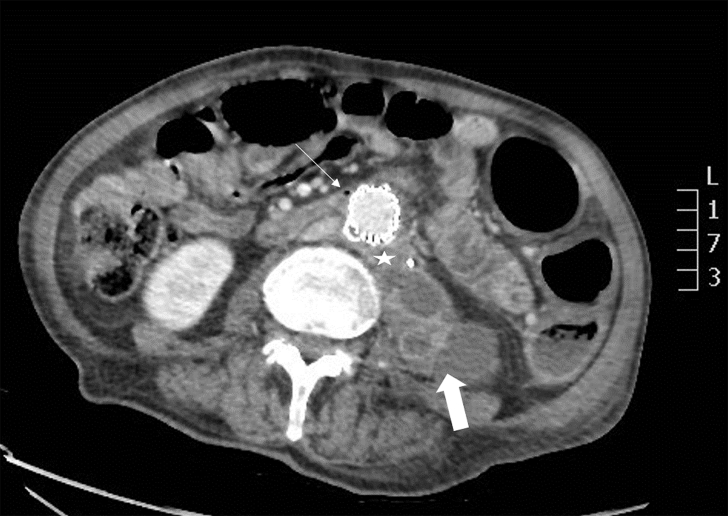

Ten months post-operatively the patient was re-admitted with significantly raised inflammatory parameters (CRP 230 mg/L; leukocytosis 25 × 10*9/L). He had no fever. CT imaging showed new peri-aortic abscesses (Fig. 1). Percutaneous drainage of the abscesses and IV antibiotics were applied, resulting in improvement of the inflammatory status (CRP 10 mg/L; leukocytosis 10 × 10*9/L). The patient then agreed to undergo revision surgery, being the final resort for some durable quality of life. Meanwhile, he was completely exhausted having lost 23 kg in weight loss over the previous year.

Figure 1.

CT angiography shows a peri-aortic inflammatory cuff (white star), an air bubble (small arrow), and abscesses on the psoas muscle (bold arrow).

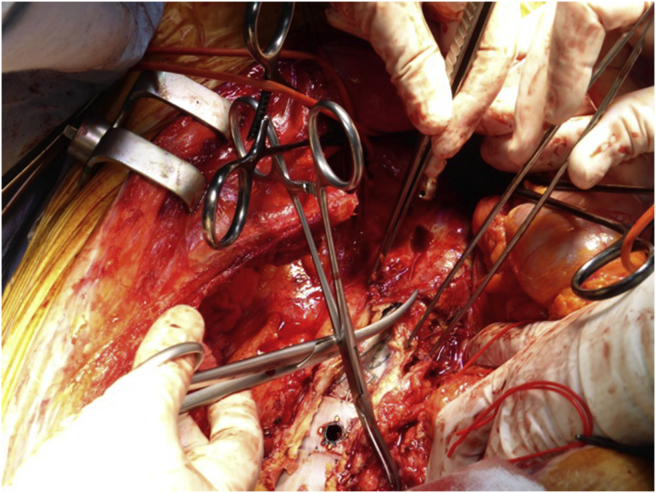

A staged procedure was performed. First, an axillo-bifemoral bypass was performed to reduce cardiac afterload during aortic clamping and to guarantee perfusion of the legs. Two days later both superficial femoral and great saphenous veins were harvested. The complete endograft with visceral stents was explanted through thoraco-phreno-laparotomy at the level of the eighth rib (Fig. 2). An unexpected aorto-duodenal fistula was closed. An autologous in situ venous reconstruction was performed (Fig. 3). At the end the axillo-bifemoral bypass was removed. The total operative time was 8.5 hours; renal ischaemia time after intra-arterial cooling was 45 and 75 minutes, respectively; bowel ischaemia time was 90 minutes.

Figure 2.

Operative image of the endograft explantation.

Figure 3.

Operative image of the autologous in situ venous reconstruction with proximal anastomosis (bold arrow), hidden right renal bypass (small arrow), superior mesenteric artery bypass (*), and left renal bypass (**).

Two revisions were needed for bleeding. The first revision was performed while the patient was still on the operating table, for bleeding from the proximal anastomosis. During the second revision for a small bleed on a side branch of the venous graft, small bowel ischaemia appeared despite patent bypasses. A subtotal colectomy and segmental small bowel resection were performed. Finally, the patient developed myocardial infarction and eventually multi-organ failure. The patient died 3 days post-operatively.

Discussion

Reports on conventional endograft infection state that surgical management is the best option for patients with good life expectancy.1, 2, 4, 5 The decision should balance the patient's comorbidities, life expectancy, and symptoms. Literature shows that infected endografts can be treated surgically with acceptable morbidity and mortality.1, 4, 5 Overall mortality rates 1–2 years after explantation of the infected endograft are reported between 21% and 35%.2, 4, 5 Outcomes after preservation of the grafts are worse with an overall mortality varying from 45% to 100%.6

These results cannot just be transferred to patients with FEVAR, as the surgery is more complex and patients might be in a poorer general condition than patients undergoing EVAR, as FEVAR is reserved for more complex cases. The present patient had a high grade endograft infection with intra-abdominal abscesses that was treated conservatively for 1 year with unfavourable results. Radical surgery was proposed from the outset, but the patient refused. He had multiple comorbidities with a high operative risk. However, following the conservative measures, he had a very poor quality of life, so the decision for surgical management was eventually made when he was in even worse general condition. Unfortunately, the post-operative complications were fatal. Earlier revision surgery could potentially have increased his chances of survival. It is not thought that vein harvesting in a separate stage or the choice for homologous graft would have influenced the short-term outcome.

There is no defined optimal management for aortic endograft infection, be it medical or surgical, therefore an individualised therapeutic strategy should be designed for each patient.

Conclusion

Infectious complications after FEVAR cause significant problems. Radical surgical management is seen as the last resort if maximum conservative measures fail. Mortality and morbidity rates are very high in these ill patients. Perhaps earlier decisions on radical revision surgery could improve survival rates. This study demonstrates that in situ autologous venous reconstruction is technically feasible.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Setacci C., Chisci E., Setacci F., Ercolini L., de Donato G., Troisi N. How to diagnose and manage infected endografts after endovascular aneurysm repair. Aorta. 2014;2(6):255–264. doi: 10.12945/j.aorta.2014.14-036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fatima J., Duncan A.A., de Grandis E., Oderich G.S., Kalra M., Gloviczki P. Treatment strategies and outcomes in patients with infected aortic endografts. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao R., Lane T.R.A., Franklin I.J., Davies A.H. Open repair versus fenestrated endovascular aneurysm repair of juxtarenal aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:242–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davila V.J., Stone W., Duncan A.A., Wood E., Jordan W.D., Zea N. A multicenter experience with the surgical treatment of infected abdominal aortic endografts. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:877–883. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.04.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smeds M.R., Duncan A.A., Harlander-Locke M.P., Lawrence P.F., Lyden S., Fatima J. Treatment and outcomes of aortic endograft infection. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.08.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moulakakis K.G., Sfyroeras G.S., Mylonas S.N., Mantas G., Papapetrou A., Antonopoulos C.N. Outcome after preservation of infected abdominal aortic endografts. J Endovasc Ther. 2014;21:448–455. doi: 10.1583/13-4575MR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]