Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a pathogen associated with severe infections in companion animals present in the community, and it is diagnosed in animals admitted to veterinary hospitals. However, reports that describe the circulation of MRSA in animal populations and veterinary settings in Latin America are scarce. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the prevalence and investigate the molecular epidemiology of MRSA in the environment of the largest veterinary teaching hospital in Costa Rica. Preselected contact surfaces were sampled twice within a 6-week period. Antimicrobial resistance, SCCmec type, Panton-Valentine leukocidin screening, USA type, and clonality were assessed in all recovered isolates. Overall, MRSA was isolated from 26.5% (27/102) of the surfaces sampled, with doors, desks, and examination tables most frequently contaminated. Molecular analysis demonstrated a variety of surfaces from different sections of the hospital contaminated by three highly related clones/pulsotypes. All, but one of the isolates were characterized as multidrug-resistant SCCmec type IV-USA700, a strain sporadically described in other countries and often classified as community acquired. The detection and frequency of this unique strain in this veterinary setting suggest Costa Rica has a distinctive MRSA ecology when compared with other countries/regions. The high level of environmental contamination highlights the necessity to establish and enforce standard cleaning and disinfection protocols to minimize further spread of this pathogen and reduce the risk of nosocomial and/or occupational transmission of MRSA.

Keywords: : environment, MRSA, USA700, veterinary hospital

Introduction

Worldwide, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a well-known pathogen associated with severe infections in hospitals and the community (McDougal et al. 2003, Otter and French 2010, Chuang and Huang 2013, CDC 2016). In Latin America, reports of MRSA colonization and infections are scarce. Nonetheless, this pathogen is considered one of the leading causes of nosocomial infections in human hospitals, with prevalence ranging from 6% in Cuba to as high as 80% in Chile and Peru (Loureiro et al. 2000, PAHO 2005, Ribeiro et al. 2005, Guzmán-Blanco et al. 2009).

In the case of Costa Rica, the Pan American Health Organization reports that the prevalence of MRSA among hospital-associated S. aureus isolates has increased from 45% to 70% between 2002 and 2007 (PAHO). These data are also supported by two recent studies performed at the National Children's Hospital of Costa Rica, where 44–61% of the S. aureus isolates collected at the hospital's bacteriology laboratory were classified as methicillin resistant (Jimenez-Truque et al. 2014, Yock-Corrales et al. 2014).

In companion animal veterinary hospitals, MRSA outbreaks have been reported in patients and personnel in numerous countries (Leonard et al. 2006, van Duijkeren et al. 2010, Schwaber et al. 2013, Grönlund Andersson et al. 2014, Steinman et al. 2015). However, reports describing the circulation of MRSA in animal populations and veterinary settings in Latin America are scarce. Only two peer-reviewed publications appear to be available on this subject. One of them describes the presence of MRSA in pigs in Peru (Arriola et al. 2011) and the second publication reports the prevalence of MRSA among dogs and cats in Brazil, where only one cat was positive (Quitoco et al. 2013).

It is well known that MRSA can survive in the environment for long periods of time and remain infectious (Wagenvoort et al. 2000, Kramer et al. 2006). In fact, it has been suggested that contaminated contact surfaces within veterinary settings could have been involved in the transmission of MRSA to patients (Van Balen et al. 2014). As a result, contact surfaces have been considered a plausible reservoir for this pathogen and a potential source for nosocomial and occupational infections within veterinary hospitals (Weese 2004, Bergström et al. 2012b, Van Balen et al. 2013). As such, strict measures for the control and prevention of MRSA transmission within veterinary settings are indicated.

In recent years, the Veterinary Hospital of Minor Species and Wildlife of the Veterinary Medicine School at The National University of Costa Rica (HEMS-UNA, Spanish acronym for Hospital de Especies Menores y Silvestres de la Universidad Nacional) experienced a number of small-scale MRSA outbreaks involving veterinary students and personnel. However, since the epidemiology of MRSA in veterinary hospitals in Latin America is unknown, targeted implementation of specific interventions (including cleaning and disinfection protocols) has been limited. For this reason, we performed a multiple-point cross-sectional study to determine the presence and characteristics of MRSA strains on contact surfaces at the only academic referral veterinary hospital in Costa Rica.

The aims of this study were as follows: (1) document the extent of MRSA environmental contamination at HEMS-UNA, (2) identify the most commonly contaminated surfaces that could later be targeted for active cleaning and disinfection, (3) phenotypically and genotypically characterize all MRSA isolates to establish epidemiological significance and plausible origin of strains, and (4) to study its ecology in such a setting.

Materials and Methods

Locations and surfaces sampled

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the only tertiary referral and teaching veterinary hospital in Costa Rica (HEMS-UNA) from May to June 2013. During this year, the referral hospital received ∼3472 patients. Nearly 80% of these cases required hospitalization with a 6-day average hospitalization time. The hospital provides the following services: internal medicine, dermatology, neurology, orthopedics, surgery, physical therapy, oncology, intensive care, imaging (ultrasonography, radiology, and endoscopy), and laboratory. The equipment and personnel in these services are used with both domestic and wildlife species (i.e., monkeys, parrots, macaws, raccoons, turtles, hamsters, rabbits, and big wild felines, among others).

An initial sampling of 51 surfaces (Table 1), representing ∼80% of the facility, was completed. Six weeks later, this sampling was repeated. Surfaces were categorized as human, animal, or mixed (human and animal) contact as previously described (Hoet et al. 2011) (Table 1). Human contact surfaces were defined as those contacted by multiple people and out of reach for animals (e.g., doors); animal contact surfaces were those primarily in direct contact with multiple animals (e.g., examination tables); and mixed contact surfaces were those in contact with both people and animals (e.g., ultrasound transducers). These surfaces were selected based on the fact that they are highly touched or enter in direct human/animal contact multiple times a day.

Table 1.

Environmental Contact Surfaces Sampled at the Veterinary Hospital of Minor Species and Wildlife of the Veterinary Medicine School at the National University of Costa Rica (HEMS-UNA)

| Location | Human contact | Animal contact | Mixed contact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Examination room 1 | Light switches•a | n/a | Examination table, door, and equipment▴b |

| Examination room 3 | Light switches•a | n/a | Examination table, door, and equipment▴b |

| Feline internal medicine | Faucet• | Cages▴c | n/a |

| Doors▴d | Examination tables▴e | ||

| Internal medicine A | Chairs▴f | Examination tables▴g | n/a |

| Doors▴d | Cages (small)▴h | ||

| Office desk▴ | Cages (large)▴i | ||

| Medical record's desk▴ | |||

| Keyboards•j | |||

| Phone• | |||

| Light switch• | |||

| Internal medicine B | Door▴ | Cages (small)▴h | n/a |

| Light switches• | Cages (large)▴i | ||

| Examination table▴ | |||

| Ultrasound room | Door▴ | Examination tables▴e | Ultrasound transducers• |

| Radiology room | n/a | n/a | Examination table and doors▴k |

| Lead vests and cassettes▴l | |||

| Physical therapy room | n/a | n/a | Physical therapy pool walls▴ |

| Presurgery room | Cabinet drawers▴m | Examination tables▴e | n/a |

| Doors▴d | |||

| Presurgery hall | Soap dispensers•n | n/a | n/a |

| Shelf handles▴ | |||

| Surgery rooms | n/a | Surgery tables▴g | n/a |

| Warming pad▴ | |||

| Oxygen monitor• | |||

| Orthopedic ward 1 | Door▴ | Cages▴h | n/a |

| Orthopedic ward 2 | Door▴ | Cages▴h | n/a |

| Infectious diseases ward | Door▴ | Cages▴i | n/a |

| Examination table▴ | |||

| Miscellaneous | Refrigerator▴ | Gurneys▴o | n/a |

| Microwave• | Muzzles•p | ||

| Light switches•a | Bowls•q | ||

| Washer and dryer controls• |

Sample collected with swab.

Sample collected with electrostatic cloth.

Two light switches were sampled as a pool.

One table, one door, and room equipment (stethoscope, rectal thermometer, and hand soap dispenser) were sampled as a pool.

Eight cages were sampled as a pool.

Two doors were sampled as a pool.

Two tables were sampled as a pool.

Four chairs were sampled as a pool.

Four tables were sampled as a pool.

Four cages were sampled as a pool.

Three cages were sampled as a pool.

Two keyboards were sampled as a pool.

One table and two doors were sampled as a pool.

Four vests and two cassettes were sampled as a pool.

Two cabinets were sampled as a pool.

Two dispensers were sampled as a pool.

Two gurneys were sampled as a pool.

Six muzzles were sampled as a pool.

Ten bowls were sampled as a pool.

n/a, not applied.

At the time of this study, the HEMS-UNA had no standardized cleaning and disinfection protocols in place. Instead, an informal routine was used, including one person in charge of the general cleaning (e.g., floor, doors, glasses, restrooms, and offices) and veterinary assistants and students in charge of cleaning the work surfaces (e.g., examination tables, cages, equipment, and surgery tables). General cleaning was performed twice daily. Most commonly used cleaning products included bleach and commercial disinfectant formulas.

Sampling techniques and processing

Two sampling techniques were used depending of the size of the surface to be sampled (Hoet et al. 2011). Electrostatic cloths (Swiffer®; Proctor and Gamble, Cincinnati, OH) were used to sample large surfaces to be able to cover the entire area of the surface (e.g., examination tables and cages). Cotton swabs premoistened in sterile trypticase soy broth (TSB, Becton; Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) were used to sample small surfaces (e.g., telephones and soap dispensers) (Table 1). In some cases, multiple items of the same surface type (e.g., two or more muzzles) or simply multiple surfaces (e.g., examination tables and doors) in the same area were sampled as a pool with the same cloth or swab (Table 1). These samples are referred to as pooled samples throughout this article.

After sampling, electrostatic cloths were folded and placed in a sterile bag to which TSB was added. In the case of cotton swabs, they were placed in sterile tubes with 2 mL of TSB. All samples were incubated aerobically at 35°C for 24 h as previously described (Weese et al. 2004, Hoet et al. 2011). For quality assurance, negative and positive controls were included in every sampling.

Isolation and identification

Staphylococcal isolation and characterization were performed as previously described (Hoet et al. 2011). Plausible S. aureus isolates were confirmed with the VITEK identifier Compact 2 (Biomèriux®, Marcy l'Etoile, France) using the GP card. Mannitol salt agar plates with 2 μg/mL oxacillin (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) were used to phenotypically test for methicillin resistance.

mecA confirmation, Staphylococcal chromosome cassette mec typing, Panton-Valentine leukocidin screening, and pulse-field gel electrophoresis

Presence of the mecA gene and SCCmec types (I–VI) were determined in all MRSA isolates (Borraz Ordáz 2006, Milheirico et al. 2007) using the following S. aureus strains as controls: ATCC 43300 (Type II), ANS46 (Type III), WIS (Type V), and HDE288 (Type VI). In addition, all isolates were screened for the presence of Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) genes (Lina et al. 1999) using NRS123 (form the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in S. aureus) and ATCC 43300 as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of SmaI-digested chromosomal DNA was performed as previously described (Van Balen et al. 2013, CDC/Pulse-Net) using the Salmonella serotype Branderup strain H9812 digested with XbaI as a molecular size marker. Strains with ≥98% similarity were considered the same clone, and a similarity coefficient of ≥80% was selected to define clusters of highly related clones (Van Balen et al. 2013). Designation of USA types was performed comparing our isolates to a CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) database containing 100 S. aureus strains with the most typical band patterns for each USA type, using >80% similarity as the cutoff point. This database was provided by the Antimicrobial Resistance and Characterization Laboratory, Clinical and Environmental Microbiology Branch, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion of the CDC (Atlanta, GA).

Antimicrobial susceptibility test (phenotyping)

Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion (CLSI 2013) was used to detect antimicrobial susceptibility to the following: ampicillin (10 μg), amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (20–10 μg), cephalothin (30 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), doxycycline (30 μg), and enrofloxacin (5 μg). In addition, the VITEK 2 Compact using the AST-P577 card was used to determine susceptibility to the following: amikacin, cefoxitin, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, levofloxacin, linezolid, minocycline, moxifloxacin, nitrofurantoin, oxacillin, quinupristin–dalfopristin, rifampin, teicoplanin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, and vancomycin. MRSA ATCC 43300 and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus ATCC 25923 were used as control strains with recognized susceptibility breakpoints described by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI 2013). Multidrug resistance was defined as resistance to three or more classes of antimicrobials, including beta-lactams, as previously described (Hoet et al. 2011).

Data analysis

The data were analyzed and described separately according to type of contact surfaces (human, animal, or mixed). A chi-squared test was conducted to compare the relationship between human, animal, and mixed contact surfaces. Statistical significance was determined at the cutoff value of 0.05 (p ≤ 0.05).

Results

Environmental MRSA detection

A total of 102 environmental samples were collected at the HEMS-UNA. Overall, 40.2% (41/102) and 26.5% (27/102) of the surfaces sampled were positive for S. aureus and MRSA, respectively. On average, 49.0% (50/102) of the surfaces sampled were classified as human contact, 39.2% as (40/102) animal contact, and 11.8% as (12/102) mixed contact. Table 2 summarizes the distribution of MRSA contamination by type of contact surface and sampling period. When comparing the overall prevalence of MRSA between the three types of surfaces (human, animal, and mixed contact), no statistical difference was observed (p ≤ 0.16).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Human, Animal, and Mixed Contact Surfaces at the Veterinary Hospital of Minor Species and Wildlife of the Veterinary Medicine School at the National University of Costa Rica (HEMS-UNA)

| Human contact MRSA/samples collected (%) | Animal contact MRSA/samples collected (%) | Mixed contact MRSA/samples collected (%) | Total MRSA/samples collected (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First sampling | 7/25 (28.0) | 7/20 (35.0) | 2/6 (33.3) | 16/51 (31.4) |

| Second sampling | 5/25 (20.0) | 5/20 (25.0) | 1/6 (16.7) | 11/51 (21.6) |

| Total | 12/50 (24.0) | 12/40 (30.0) | 3/12 (25.0) | 27/102 (26.5) |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

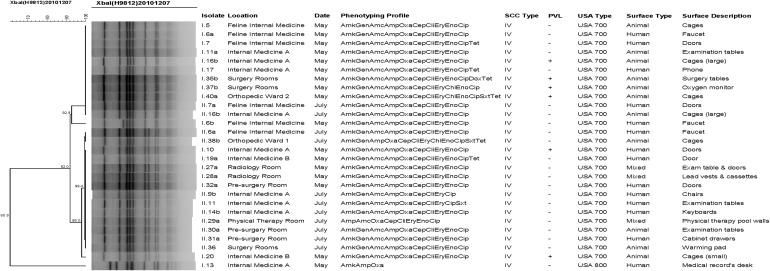

Of the 27 MRSA-positive surfaces, only 4 (the faucet [isolate numbers I.6a, I.6b, and II.6a] and doors [I.7 and II.7b] of the feline internal medicine area, and the examination tables [I.11a and II.11] and large cages [I.16b and II.16b] of internal medicine A area) were contaminated on both sampling dates. None of the MRSA strains found on these four surfaces (from the first and second sampling) were clonal, but they were highly related (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Dendogram of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates obtained from the environment at the Veterinary Hospital of Minor Species and Wildlife of the Veterinary Medicine School at the National University of Costa Rica (HEMS-UNA). Amk, amikacin; Gen, gentamicin; Amc, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid; Amp, ampicillin; Oxa, oxacillin; Cep, cephalothin; Cli, clindamycin; Ery, erythromycin; Chl, chloramphenicol; Eno, enrofloxacin; Cip, ciprofloxacin; Sxt, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole; Dox, doxycycline; Tet, tetracycline.

Since, in some cases, only two samples (one from each sampling date) were collected per surface, proportion of contamination by surface will only be discussed in those with a representative number of samples. In the case of human contact surfaces, 31.3% (5/16) of the access doors and 25.0% (1/4) of the desks used by the personnel were MRSA positive. On the other hand, among animal contact surfaces, 37.5% (6/16) of the cages and 28.6% (4/14) of the examination-surgery tables were found MRSA positive.

Genotypic analysis

From the 27 MRSA-positive surfaces, a total of 28 isolates were phenotypically and genotypically characterized (2 isolates were obtained from the faucets in the feline internal medicine ward during the first sampling and determined to be 2 different MRSA clones). The presence of the mecA gene was confirmed in all 28 MRSA isolates, and all of them were characterized as SCCmec type IV. PVL screening revealed 6/28 (21.4%) positive isolates (Fig. 1). Based on their PFGE patterns, 27 isolates were classified as USA700 (of which 6 were PVL positive) and 1 as USA800 (PVL negative) (Fig. 1); both clones are usually considered community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA).

Dendrogram analysis revealed that all but one isolate were highly related and distributed in a single cluster, represented by three pulsotypes (Fig. 1). It was also noted that some MRSA strains (isolates sharing the same phenotypic profile, SCCmec type and pulsotype) were contaminating different areas of the hospital during the same sampling date. Examples of this contamination pattern include isolates I.10, I.20, I.27a, and I.32a (found in internal medicine A, internal medicine B, radiology room, and presurgery room, respectively, during the first sampling) and II.6a, II.14b, II.30a, and II.36 (found in the feline internal medicine, internal medicine A, presurgery room, and the surgery room, respectively, during the second sampling) (Fig. 1).

Antimicrobial susceptibility

Ten antimicrobial-resistant profiles were identified from 28 MRSA isolates (Table 3). All 27 USA700 isolates showed a high level of multidrug resistance with complex phenotypic profiles. In this group, 66.7% (18/27), 18.5% (5/27), and 7.4% (2/27) were resistant to 5, 6, and 8 antimicrobial classes, respectively. In contrast, the USA800 was only resistant to beta-lactams and aminoglycosides. None of the clindamycin-resistant isolates showed inducible resistance. All MRSA isolates were susceptible to levofloxacin, linezolid, minocycline, nitrofurantoin, quinupristin–dalfopristin, rifampin, teicoplanin, and vancomycin.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Environmental Isolates from the Veterinary Hospital of Minor Species and Wildlife of the Veterinary Medicine School at the National University of Costa Rica (HEMS-UNA)

| Phenotypic profile | No. of Abx classes | No. of isolates | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| AmkAmpOxa | 2 | 1 | 3.6 |

| AmpAmcOxaCepCliEryEnoCip | 4 | 1 | 3.6 |

| AmkGenAmcAmpOxaCepCliEryCip | 5 | 1 | 3.6 |

| AmkGenAmcAmpOxaCepCliEryEnoCip | 5 | 17 | 60.7 |

| AmkGenAmcAmpOxaCepCliEryChlEnoCip | 6 | 1 | 3.6 |

| AmkGenAmcAmpOxaCepCliEryEnoCipDoxTet | 6 | 1 | 3.6 |

| AmkGenAmcAmpOxaCepCliEryEnoCipTet | 6 | 3 | 10.7 |

| AmkGenAmcAmpOxaCepCliEryCipSxt | 6 | 1 | 3.6 |

| AmkGenAmcAmpOxaCepCliEryChlEnoCipSxtTet | 8 | 1 | 3.6 |

| AmkGenAmpOxaCepCliEryChlEnoCipSxtTet | 8 | 1 | 3.6 |

Abx, antibiotic; Amk, amikacin; Gen, gentamicin; Amc, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid; Amp, ampicillin; Oxa, oxacillin; Cep, cephalothin; Cli, clindamycin; Ery, erythromycin; Chl, chloramphenicol, Eno, enrofloxacin; Cip, ciprofloxacin; Sxt, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole; Dox, doxycycline; Tet, tetracycline.

Discussion

This study reports the high level of environmental contamination (26.5%) with a multidrug-resistant CA-MRSA in the largest veterinary teaching hospital in Costa Rica. Of interest is the fact that, in other areas of the world (primarily North America, Europe, and some countries in Asia), similar settings have described HA-MRSA outnumbering community-associated strains in regard to environmental contamination (Loeffler et al. 2005, Heller et al. 2009, Hoet et al. 2011, Bergström et al. 2012a, Van Balen et al. 2013,). In addition, the MRSA strain described in this study (USA700) does not seem to be particularly prevalent in other countries (Tenover et al. 2008, 2012, Otter and French 2010, Chuang and Huang 2013, Hoet et al. 2013, Hidalgo et al. 2015).

However, it has been commonly suggested that the predominant MRSA strain(s) present in a healthcare setting is usually a reflection of the most prevalent clones found in the general community served by that healthcare facility. It appears that this holds true in Costa Rica, where recent studies found USA700 was the most common strain type associated with MRSA soft tissue and invasive infections in children (Jimenez-Truque et al. 2014, Yock-Corrales et al. 2014).

Unfortunately, to date, few studies have investigated MRSA (especially in animal populations) in Latin America (Guzmán-Blanco et al. 2009, Rodríguez-Noriega et al. 2010, Arriola et al. 2011, Quitoco et al. 2013, Jimenez-Truque et al. 2014, Yock-Corrales et al. 2014), which makes this study unique, but limits the authors' ability to analyze and interpret the results. Nonetheless, the 26.5% CA-MRSA prevalence found in the environment was almost twice as high as the prevalence reported in other regions (Weese et al. 2004, Loeffler et al. 2005, Heller et al. 2009, Murphy et al. 2010, Hoet et al. 2011, Van Balen et al. 2013) and, as mentioned, it is in contrast to the predominant presence of HA-MRSA strains that are usually described in similar settings.

The wide variety of contaminated contact surfaces across different areas of the HEMS-UNA with multidrug-resistant MRSA is concerning. Of the 51 surfaces selected to be sampled, almost half (23/51) were found positive on either one or both sampling dates. The most prevalent surfaces in this study, doors, desks, cages, and examination tables, have also been described as commonly contaminated in other studies (Oie et al. 2002, Hoet et al. 2011, Bergström et al. 2012b, Van Balen et al. 2013), probably due to the fact that they are touched by numerous people and/or animals several times per day. Once contaminated, a surface could become a potential source for on-going MRSA transmission.

The fact that 21.4% of the MRSA isolates found in the hospital environment harbored PVL genes is also concerning. PVL is a leukocidal toxin that has been suggested to increase the virulence potential of CA-MRSA strains and is often associated with severe skin and soft tissue infections (Boyle-Vavra and Daum 2007, Wu et al. 2010, Guillén et al. 2016, Hewagama et al. 2016, Immergluck et al. 2017). Outbreaks of MRSA-PVL-positive strains have been reported in both healthcare and community settings, in some cases involving healthy individuals with no MRSA-associated risk factors (Tang et al. 2007, Maltezou et al. 2009, Higashiyama et al. 2011). These studies highlight how MRSA-PVL-positive strains could be easily spread (to other individuals and/or the environment) within a particular facility, especially when appropriate precautions (including—but not exclusive to—infection control, preventive measures, and personal hygiene) are not followed.

At HEMS-UNA in particular, this environmental investigation was performed after a number of small-scale undocumented MRSA outbreaks occurred among students and staff. Even though it is not possible to determine the role that the hospital environment could have played during the outbreaks, two conclusions could be drawn based on our results. First, the high level of environmental contamination clearly demonstrates that MRSA-PVL-positive and MRSA-PVL-negative strains are being introduced and spread throughout the hospital, probably facilitated by inadequate cleaning and disinfection. Second, the presence of MRSA-PVL-positive isolates on a number of high-contact surfaces increases the exposure levels of personnel (occupational) and patients (nosocomial) to this highly pathogenic bacterium.

From the occupational point of view, it has been found that up to 42% of healthcare workers' hands become “contaminated” after being in contact with surfaces present in rooms of patients infected with MRSA (Boyce et al. 1997, Bhalla et al. 2004). On their own, contaminated hands are not equivalent to being colonized or infected with this pathogen, but it does increase the probability of either of these two scenarios to occur. In addition, contaminated hands could be involved in the transmission of MRSA to other coworkers and patients, as well as the contamination of other surfaces and/or areas of the hospital.

From the nosocomial point of view, it is important to recognize that animal patients often have direct and prolonged contact with their surroundings (e.g., sniffing, licking, or lying on the floor), in this case, the hospital environment. This reality increases the exposure to surfaces that, if contaminated, could potentially lead to the development of MRSA infections, especially in patients with open wounds or that are immunocompromised. Moreover, this is even more concerning in those areas of the hospital where patients undergo invasive procedures. Such is the case of the presurgery and surgery rooms, where all of the animal contact surfaces sampled were found positive for MRSA.

Due to the scope and design of this study, it is difficult to determine the source(s) of the MRSA strains present in the HEMS-UNA environment. Nonetheless, PFGE results showed that all but one of the isolates were clonally related, suggesting a horizontal dissemination and/or independent introduction from a common or few sources. During the environmental sampling dates, there were no known clinical cases treated or hospitalized with MRSA infections at the hospital. Therefore, an unidentified infected/colonized animal(s) and/or human(s) entering the hospital is the most likely source responsible for introducing the MRSA strain into the hospital.

Once inside the hospital, inadequate cleaning/disinfection and lax biosecurity/prevention protocols were the most probable factors contributing to the dissemination of MRSA across the veterinary facility. This hypothesis is based on facts discussed in previous studies, where the implementation of appropriate and targeted cleaning and disinfection protocols can effectively reduce MRSA environmental contamination (Rampling et al. 2001, Boyce et al. 2009, Jinadatha et al. 2015, Yuen et al. 2015, Semret et al. 2016).

Considering the plausible occupational and nosocomial implications of a heavily contaminated environment in a veterinary hospital, it is critical to improve current cleaning and disinfection practices at the HEMS-UNA. Based on the results obtained from this study, the administration has already started to develop a more standardized and adequate protocol customized to meet the HEMS-UNA needs in regard to prevention and control of MRSA and other important nosocomial pathogens. Future studies will be needed to evaluate the effectiveness and compliance of the hospital's personnel to the newly established protocols.

Last, samplings were performed for a short period of time, limiting our ability to evaluate the movement and maintenance of MRSA in the hospital environment. Nonetheless, the information acquired could be used as a reference to develop a larger scale project in the future. In addition, due to relevant differences between veterinary hospitals (including infrastructure and management), the possibility of extrapolating our results to other settings is limited. Still, this is the first study reporting MRSA environmental contamination in a veterinary teaching hospital in Central America, and could be used as a starting point for other countries in the same region.

Conclusion

It is noteworthy and concerning to identify a multidrug-resistant CA-MRSA strain (USA700), unfrequently reported in other countries, contaminating 26.5% surfaces at the largest veterinary teaching hospital in Costa Rica. In addition, 92.8% of the isolates recovered were resistant to ≥5 antimicrobial classes and 21.4% were PVL positive, which translate to a higher risk of life-threatening infections if nosocomial or occupational transmission of these highly pathogenic bacteria were to occur within this setting. Since USA700 has also been associated with soft tissue and invasive infections (i.e., infectious endocarditis) in children in this country, further research is needed to understand if indeed Costa Rica has a unique MRSA ecology in which this strain thrives. In conclusion, this report showed that the epidemiology and ecology of MRSA in veterinary hospitals are not universal, a fact that must be recognized by the veterinary community when managing this pathogen in their practices.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the personnel from the Bacteriology Laboratory (National University and University of Costa Rica) for their technical and logistical assistance, and Carlos Chacón-Díaz, Yeimy Ramírez, and José Pablo Solano for their technical assistance and helpful discussions. The following reagent was provided by the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (NARSA) for distribution by BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: Staphylococcus aureus, Strain C1999000459 (NRS123) as a PVL-positive control.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Arriola C, Güere M, Larsen J, Skov R, et al. Presence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in pigs in Peru. PLoS One 2011; 6:e28529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergström A, Gustafsson C, Leander M, Fredriksson M, et al. Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococci in surgically treated dogs and the environment in a Swedish animal hospital. J Small Anim Pract 2012a; 53:404–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergström K, Nyman G, Widgren S, Johnston C, et al. Infection prevention and control interventions in the first outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in an equine hospital in Sweden. Acta Vet Scand 2012b; 54:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla A, Pults N, Gries D, Ray A, et al. Acquisition of nosocomial pathogens on hands after contact with environmental surfaces near hospitalized patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2004; 25:164–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borraz Ordáz C. Epidemiología de la Resistencia a Meticilina en Cepas de Staphylococcus aureus aisladas en Hospitales Españoles. Patología y Terapéutica Experimental. Barcelona: Universidad de Barcelona; 2006:203 [Google Scholar]

- Boyce J, Havill N, Dumigan D, Golebiewski M, et al. Monitoring the effectiveness of hospital cleaning practices by use of an adenosine triphosphatebioluminescence assay. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009; 30:678–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce J, Potter-Bynoe G, Chenevert C, King T. Environmental contamination due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Possible infection control implications. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1997; 18:622–627 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle-Vavra S, Daum RS. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: The role of Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Lab Invest 2007; 87:3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. Available at www.cdc.gov/mrsa [Google Scholar]

- CDC/Pulse-Net. Oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on PulseNet (OPN): Laboratory protocols for molecular typing of S. aureus by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Available at www.cdc.gov/mrsa/pdf/ar_mras_PFGE_s_aureus.pdf Accessed August7, 2017

- Chuang Y, Huang Y. Molecular epidemiology of community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Asia. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:698–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated From Animals; Approved Standard–Fourth Edition. VET 01-A4. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), 2013:94 [Google Scholar]

- Grönlund Andersson U, Wallensten A, Hæggman S, Greko C, et al. Outbreaks of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among staff and dogs in Swedish small animal hospitals. Scand J Infect Dis 2014; 46:310–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillén R, Carpinelli L, Rodríguez F, Castro H, et al. Community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Paraguayan children: Clinical, phenotypic and genotypic characterization. Rev Chilena de Infectol 2016; 33:609–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Blanco M, Mejia C, Isturiz R, Alvarez C, et al. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Latin America. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2009; 34:304–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller J, Armstrong S, Girvan E, Reid S, et al. Prevalence and distribution of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus within the environment and staff of a university veterinary clinic. J Small Anim Pract 2009; 50:168–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewagama S, Spelman T, Woolley M, McLeod J, et al. The epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus and Panton-Valentine leucocidin (pvl) in Central Australia, 2006–2010. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16:382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo M, Carvajal L, Rincón S, Faccini-Martínez Á, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 Latin American variant in patients undergoing hemodialysis and HIV infected in a hospital in Bogotá, Colombia. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0140748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashiyama M, Ito T, Han X, Nishiyama J, et al. Trial to control an outbreak of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at a boarding school in Japan. Am J Infect Control 2011; 39:858–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoet A, Van Balen J, Nava-Hoet R, Bateman S, et al. Epidemiological profiling of MRSA positive dogs arriving at a veterinary teaching hospital. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2013; 13:385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoet AE, Johnson A, Nava-Hoet RC, Bateman S, et al. Environmental methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a veterinary teaching hospital during a nonoutbreak period. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011; 11:609–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immergluck L, Jain S, Ray S, Mayberry R, et al. Risk of skin and soft tissue infections among children found to be Staphylococcus aureus MRSA USA300 carriers. West J Emerg Med 2017; 18:201–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Truque N, Saye E, Thomsen I, Herrera M, et al. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Costa Rican children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33:180–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinadatha C, Villamaria F, Restrepo M, Ganachari-Mallappa N, et al. Is the pulsed xenon ultraviolet light no-touch disinfection system effective on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the absence of manual cleaning? Am J Infect Control 2015; 43:878–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer A, Schwebke I, Kampf G. How long do nosocomial pathogens persist on inanimate surfaces? A systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 2006; 6:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard F, Abbott Y, Rossney A, Quinn P, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a veterinary surgeon and five dogs in one practice. Vet Rec 2006; 158:155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lina G, Piemont Y, Godail-Gamot F, Bes M, et al. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 1999; 29:1128–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler A, Boag A, Sung J, Lindsay J, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among staff and pets in a small animal referral hospital in the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005; 56:692–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro M, Moraes B, Quadra M, Pinheiro G, et al. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from newborns in a hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2000; 95:777–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltezou H, Vourli S, Katerelos P, Maragos A, et al. Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus outbreak among healthcare workers in a long-term care facility. Int J Infect Dis 2009; 13:401–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougal L, Steward C, Killgore G, Chaitram J, et al. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: Establishing a national database. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41:5113–5120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milheirico C, Oliveira D, de Lencastre H. Update to the multiplex PCR strategy for assignment of mec element types in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007; 51:3374–3377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, Reid-Smith R, Boerlin P, Weese J, et al. Escherichia coli and selected veterinary and zoonotic pathogens isolated from environmental sites in companion animal veterinary hospitals in southern Ontario. Can Vet J 2010; 51:963–972 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oie S, Hosokawa I, Kamiya A. Contamination of room door handles by methicillin-sensitive/methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect 2002; 51:140–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otter J, French G. Molecular epidemiology of community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10:227–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAHO. Antimicrobial Resistance Staphylococcus aureus (hospital isolates)—oxacillin percentage for countries and territories of the Americas. Available at www.paho.org/data/index.php/en/mnu-topics/antimicrobial-resistance/306-staphylococces-aureus-resistant-oxacillin.html Accessed August7, 2017

- PAHO. Informe Anual de la Red de Monitoreo/Vigilancia de la Resistencia a los Antibióticos, 2004. Brasilia: Pan American Health Organization, 2005:115 [Google Scholar]

- Quitoco I, Ramundo M, Silva-Carvalho M, Souza R, et al. First report in South America of companion animal colonization by the USA1100 clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ST30) and by the European clone of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (ST71). BMC Res Notes 2013; 6:336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampling A, Wiseman S, Davis L, Hyett A, et al. Evidence that hospital hygiene is important in the control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect 2001; 49:109–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro A, Dias C, Silva-Carvalho M, Berquó L, et al. First report of infection with community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in South America. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43:1985–1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Noriega E, Seas C, Guzmán-Blanco M, Mejía C, et al. Evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Latin America. Int J Infect Dis 2010; 14:560–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaber M, Navon-Venezia S, Masarwa S, Tirosh-Levy S, et al. Clonal transmission of a rare methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus genotype between horses and staff at a veterinary teaching hospital. Vet Microbiol 2013; 162:907–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semret M, Dyachenko A, Ramman-Haddad L, Belzile E, et al. Cleaning the grey zones of hospitals: A prospective, crossover, interventional study. Am J Infect Control 2016; 44:1582–1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman A, Masarwa S, Tirosh-Levy S, Gleser D, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus spa type t002 outbreak in horses and staff at a veterinary teaching hospital after its presumed introduction by a veterinarian. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 53:2827–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C, Nguyen D, Ngo T, Nguyen T, et al. An outbreak of severe infections with community-acquired MRSA carrying the Panton-Valentine leukocidin following vaccination. PLoS One 2007; 2:e:822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenover F, McAllister S, Fosheim G, McDougal L, et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from nasal cultures collected from individuals in the United States in 2001 to 2004. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46:2837–2841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenover F, Tickler I, Goering R, Kreiswirth B, et al. Characterization of nasal and blood culture isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from patients in United States Hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:1324–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Balen J, Kelley C, Nava-Hoet R, Bateman S, et al. Presence, distribution and molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a small animal teaching hospital: A year-long active surveillance targeting dogs and their environment. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2013; 13:299–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Balen J, Mowery J, Piraino-Sandoval M, Nava-Hoet R, et al. Molecular epidemiology of environmental MRSA at an equine teaching hospital: Introduction, circulation and maintenance. Vet Res 2014; 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duijkeren E, Moleman M, Sloet van Oldruitenborgh-Oosterbaan MM, Multem J, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in horses and horse personnel: An investigation of several outbreaks. Vet Microbiol 2010; 141:96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenvoort J, Sluijsmans W, Penders R. Better environmental survival of outbreak vs. sporadic MRSA isolates. J Hosp Infect 2000; 45:231–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weese J. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in horses and horse personnel. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 2004; 20:601–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weese JS, DaCosta T, Button L, Goth K, et al. Isolation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from the environment in a veterinary teaching hospital. J Vet Intern Med 2004; 18:468–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Wang Q, Yang Y, Geng W, et al. Epidemiology and molecular characteristics of community-associated methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus from skin/soft tissue infections in a children's hospital in Beijing, China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2010; 67:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yock-Corrales A, Segreda-Constenla A, Ulloa-Gutierrez R. Infective endocarditis at Costa Rica's children's hospital, 2000–2011. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33:104–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen J, Chung T, Loke A. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) contamination in bedside surfaces of a hospital wardand the potential effectiveness of enhanced disinfection with an antimicrobial polymer surfactant. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015; 12:3026–3041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]