Abstract

Background: Clinically significant weight loss (CSWL) is ≥5% of initial weight. The purpose of the study is to determine factors associated with women achieving CSWL in Take Off Pounds Sensibly (TOPS), a national, nonprofit weight loss program.

Methods: This is a retrospective analysis of 48,674 females who joined TOPS from 2005 to 2011 and had a birth date in the database. Predictors of CSWL were evaluated using log-binomial regression and adjusted relative risks [99% CI] for participant age, initial weight, number of members per chapter, and chapter age.

Results: Older women were more likely to achieve CSWL, with women ≥70 years 1.23 (1.18, 1.28) times more likely to achieve CSWL compared to women 18 to <45 years. Women who weighed 113 to <136 kg and ≥136 kg were 1.06 (1.02, 1.10) and 1.07 (1.02, 1.14) times more likely to achieve CSWL compared to women <80 kg, respectively. Women in chapters with 25 to <35 members and ≥35 members more were 1.09 (1.05, 1.13) and 1.14 (1.10, 1.18) times more likely to achieve CSWL than those in chapters with less than 15 members. Women in older chapters were less likely to achieve CSWL, with women in chapters 10 to 20 years old 0.95 (0.92, 0.99) times as likely to lose weight as those in chapters less than 10 years old.

Conclusions: Women in TOPS were more likely to achieve CSWL if older, ≥113 kg, and in larger, newer chapters. Future studies should address ways to modify the program to improve achievement of CSWL.

Keywords: : obesity, weight management, women's health

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine defines clinically significant weight loss (CSWL) as weight loss of ≥5% of initial weight,1 an amount associated with improvements in weight-related comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, osteoarthritis, and obstructive sleep apnea.2–5 Even in weight loss studies that are deemed successful, a proportion of individuals who participate either gain weight or do not achieve CSWL.6–9 Studies of weight loss programs have shown a number of factors that are associated with CSWL, including increased program participation,10–12 social support from friends,10 longer duration interventions,11 and older age.12–14 However, these analyses have historically used data from Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP)-related interventions; studies of other weight loss programs have been lacking.

Take Off Pounds Sensibly (TOPS) is a low-cost, national, nonprofit weight loss program. TOPS costs significantly less than other weight loss programs—up to $92 per year (the annual membership fee is $32 and chapter dues can be up to $5 per month). TOPS also has more than 115,000 U.S. members in over 6,000 chapters in all 50 states.15

Approximately 95% of individuals who joined TOPS from 2005 to 2011 were women.7 While TOPS has not been evaluated in a randomized controlled trial, our previous analysis of data from 69,489 women who renewed their annual program membership for at least 1 year showed that their average weight loss was 6% of their initial weight. However, only 50% of those participants lost ≥5% of initial weight; 32% lost between 0% and <5%; and almost 18% gained weight.7 The purpose of the current study was to determine whether certain ages, weights, or chapter characteristics were associated with achieving CSWL among women participating in TOPS.

Based on the literature, we hypothesized that older women in TOPS would be more likely to achieve CSWL than younger women.12–14 We also hypothesized that women with lower baseline weights would be more likely to achieve CSWL because they might have had fewer weight loss attempts than their counterparts with higher baseline weights. It is important to determine which factors are associated with CSWL to improve the success of current and future weight loss programs.

Materials and Methods

Design and subjects

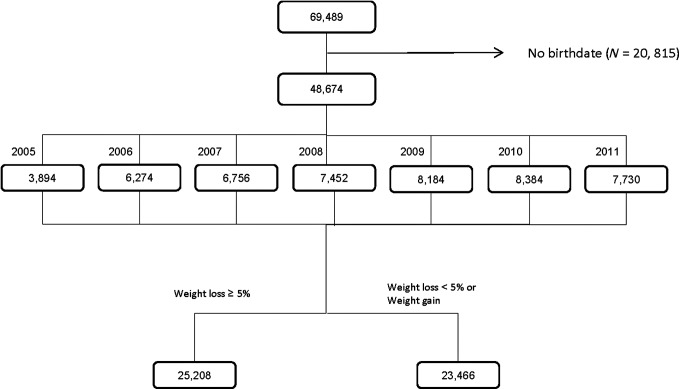

This was a retrospective analysis of female TOPS participants (Fig. 1) who renewed their annual membership at 1 year and those who renewed their annual membership consecutively at 5 years. Study participants were women who joined TOPS from 2005 to 2011 and who also had a birth date in the TOPS database.

FIG. 1.

Study inclusion.

Data source

The data source is the subset of the national database of TOPS Club, Inc. of U.S. members who joined from 2005 to 2011. The dataset contained the following variables: identification number; date of birth (DOB); TOPS start date; starting weight; renewal date (year); and renewal weight (year). Heights were only available for less than 20% in the original database; therefore, body mass index (BMI) was not used in the analysis. Information on the TOPS chapter participants who attended was also available, including number of members in the chapter at the time participants started the program and age of the chapter in 2011. The protocol was designated as expedited and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Program details

Details of the TOPS program have been published previously.7 Briefly, TOPS is a national, peer-led weight loss program that helps its members manage their weight through weekly chapter meetings. TOPS recommends the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (formerly the American Dietetic Association) Food Exchange System and U.S. Department of Agriculture MyPlate Program. TOPS provides administrative and educational materials for all chapters.

TOPS has over 100 educational programs on a broad range of topics, including healthy eating, portion control, exercise, and behavior modification. Additional programming ideas are included in their bimonthly magazine. TOPS encourages members to consult a healthcare provider to determine a goal weight. When a member reaches her goal weight, she becomes a “KOPS” member, one who is working to Keep Off Pounds Sensibly, but who continues to attend weekly meetings.

Each TOPS chapter must include at least four members, to hold elected offices: a leader, co-leader, secretary, and treasurer. A weight recorder, assistant weight recorder, and web designate may also be appointed. These are all volunteer positions. During the time these data were collected, local training and informational sessions were held for chapter officers two to four times per year. These sessions review leadership skills, TOPS programs, and effective chapter management.

Before each TOPS weekly meeting, there is a 15- to 30-minute period for private weigh-ins. Then, the meetings last ∼1 hour. The basic meeting structure is as follows: (1) recitation of TOPS pledge (optional); (2) roll call where every member's name is called and they can respond with an indication of their weight change for the previous week; (3) brief business meeting, if necessary; (4) group educational programming; and (5) recognition, and sometimes awards, for weight loss and healthy lifestyle changes. Weekly weights are documented at each local chapter by the weight recorder using detailed procedures, but the only weights that are sent to the national office are the initial weight when individuals join, at the end of each calendar year, and when they renew their annual membership.

Individuals can join an existing TOPS chapter or start a new one. Some chapters in the database were listed as having fewer than four members. When the number of members in a chapter drops below four, it is no longer listed on the TOPS website, but it continues to receive support from TOPS field staff.

Statistical analyses

Our primary outcome of interest was CSWL (≥5%) at 1 year. Weight change was dichotomized as: (1) CSWL or (2) nonsignificant weight loss/weight gain. Available covariates included the following: participant age, participant initial weight, chapter size (i.e., number of participants in the chapter at the time the individual joined), and chapter age (i.e., the number of years the chapter had been in existence).

Categorical variables were established for each covariate based on balancing group sizes and clinical relevance. For example, nearly 70% of the participants were aged 55 and older; so, to achieve balance across age groups, participants were placed in the following categories: 18 to <45; 45 to <55; 55 to <60; 60 to <65; 65 to <70; and ≥70 years. Participants were also categorized according to weight in kg (<80; 80 to 90.5; 90.5 to <102; 102 to <113.5; 113.5 to <136; and ≥136). Chapters were categorized by size (<15 members; 15 to <25 members; 25 to <35 members; and ≥35 members) and years in existence (0 to <10; 10 to <20; 20 to <30; 30 to <40; and ≥40). The first category for each variable was the reference group.

Because nearly one-third of the initial study population was excluded due to missing DOB documentation, a chi-square test of proportions was performed to determine whether those with DOB were more or less likely to achieve CSWL. A Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was used to determine if there was a difference between the starting weights of individuals with and without DOBs in the database.

Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorized baseline variables at 1 and 5 years. Multivariable log-binomial regression was used to generate adjusted relative risks (ARRs)16 for participants achieving CSWL at 1 and 5 years. For the final models, only baseline and 1- or 5-year renewal weights were used, even if the participants subsequently renewed their annual memberships. Because there were only four covariates available for the model; all variables were included simultaneously.

Orthogonal polynomial contrasts were used to test for linear trends in the risk for achieving CSWL with older starting age, higher starting weight, larger chapter size, and chapter age. A sensitivity analysis was performed, which analyzed the predictor variables as continuous data. For the analysis of continuous data, ARRs are presented for starting weight in 20 kg intervals, starting age in 10-year intervals, chapter size in 15-member intervals, and chapter age in 10-year increments.

Because of the large sample size, we used 99% confidence intervals with an alpha of <0.01 to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using SAS (SAS 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Population characteristics

The baseline characteristics for the populations at 1 and 5 years are shown in Table 1. At 1 year, the data set included 48,674 women between the ages of 18 and 105 years and weight 65.8 to 277.1 kg enrolled across 6,259 TOPS chapters. The number of participants in each TOPS chapter ranged from 0 to 242 (47 chapters had fewer than 4 participants in at least one of the years analyzed, 25 chapters had 100 or more members in at least one of the years analyzed). The age of the chapters in 2011 ranged from 0 (i.e., a new chapter) to 59 years. The percentage of individuals who achieved CSWL was 51.8%. At 5 years, the data set included 7,993 women representing 3,752 chapters, with ages 18 to 105 years and weight at TOPS start between 65.8 and 233.1 kg. Of women with a renewal weight at 5 years, 57.1% had CSWL at 1 year, and 59.8% had CSWL at 5 years.

Table 1.

Demographics of Take Off Pounds Sensibly Female Population with 1-Year Renewal (n = 48,674; Years Joined 2005–2011) and 5-Year Consecutive Annual Renewal (n = 7,993; Years Joined 2005–2007)

| Measure | Level | 1-Year renewal, N (%)a | 5-Year renewal, N (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at TOPS start | 18 to <45 years | 6,710 (13.8) | 689 (8.6) |

| 45 to <55 years | 8,785 (18.0) | 1,272 (15.9) | |

| 55 to <60 years | 6,686 (13.7) | 1,164 (14.6) | |

| 60 to <65 years | 8,662 (17.8) | 1,635 (20.5) | |

| 65 to <70 years | 8,431 (17.3) | 1,589 (19.9) | |

| ≥70 years | 9,400 (19.3) | 1,644 (20.6) | |

| Weight (kg) at TOPS start | <80 kg | 9,951 (20.4) | 1,750 (21.9) |

| 80 to <90.5 kg | 11,477 (23.6) | 1,974 (24.7) | |

| 90.5 to <102 kg | 9,932 (20.4) | 1,678 (21.0) | |

| 102 to <113.5 kg | 7,333 (15.1) | 1,135 (14.2) | |

| 113.5 to <136 kg | 7,256 (14.9) | 1,094 (13.7) | |

| ≥136 kg | 2,725 (5.6) | 362 (4.5) | |

| Chapter size at TOPS starta | 0 to <15 members | 9,825 (21.5) | 1,277 (17.0) |

| 15 to <25 members | 15,076 (32.9) | 2,169 (28.9) | |

| 25 to <35 members | 10,461 (22.9) | 1,963 (26.1) | |

| ≥35 members | 10,407 (22.7) | 2,106 (28.0) | |

| Age of chapter at TOPS start | 0 to <10 years | 10,507 (21.8) | 1,728 (21.7) |

| 10 to <20 years | 8,625 (17.9) | 1,455 (18.3) | |

| 20 to <30 years | 7,331 (15.2) | 1,319 (16.6) | |

| 30 to <40 years | 10,785 (22.4) | 2,284 (28.7) | |

| ≥40 years | 10,959 (22.7) | 1,166 (14.7) |

A total of 2,905 participants missing data on chapter size; 467 participants missing data on chapter age.

A total of 478 participants missing data on chapter size; 41 participants missing data on chapter age.

TOPS, Take Off Pounds Sensibly.

At 1 year, a higher percentage of individuals with a DOB in the database achieved CSWL than those without (51.8% vs. 46.2%, respectively, p < 0.001). There was no difference in the median interquartile range (IQR) starting weight for individuals with and without a DOB in the database, 93.9 kg (82.2–109.2) versus 93.7 kg (82.2–109.3) (p = 0.81), respectively. Among the sample with a 5-year renewal weight, achievement of CSWL was slightly higher on average in individuals with a DOB in the database at both 1 (57.1% vs. 54.4%) and 5 (59.8% vs. 56.6%) years, but these differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.13 and p = 0.07, respectively). Again, there was no difference in starting weight between individuals with and without a DOB, with the groups having median (IQR) starting weights of 92.8 kg (81.6, 107.0) and 92.5 kg (81.3, 108.9), respectively (p = 0.62).

Predictors of achieving CSWL: categorical variables

Table 2 shows the results of the log-binomial regression and the ARR [99% CI] for each category for each variable at 1 and 5 years. For participant age, at 1 and 5 years, older participants were more likely to achieve CSWL than younger participants overall.

Table 2.

Adjusted Relative Risks for Factors Associated with Female Take Off Pounds Sensibly Participants Achieving Clinically Significant Weight Loss (≥5% Weight Loss) at the 1- and 5-Year Annual Renewals with Categorical Covariates

| 1-Year renewal | 5-Year renewal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | ARR (99% CI) | p | ARR (99% CI) | p |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18 to <45 | Ref. | — | Ref. | — |

| 45 to <55 | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) | <0.0001 | 1.05 (0.93–1.19) | 0.2942 |

| 55 to <60 | 1.12 (1.07–1.18) | <0.0001 | 1.16 (1.02–1.31) | 0.0020 |

| 60 to <65 | 1.14 (1.09–1.19) | <0.0001 | 1.25 (1.11–1.40) | <0.0001 |

| 65 to <70 | 1.16 (1.11–1.21) | <0.0001 | 1.29 (1.15–1.45) | <0.0001 |

| 70 and older | 1.23 (1.18–1.28) | <0.0001 | 1.43 (1.27–1.60) | <0.0001 |

| Starting weight (kg) | ||||

| <80 | Ref. | — | Ref. | — |

| 80 to <91 | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 0.3873 | 1.05 (0.97–1.12) | 0.1096 |

| 91 to <102 | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.1615 | 1.12 (1.04–1.21) | <0.0001 |

| 102 to <113 | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.1560 | 1.14 (1.05–1.24) | <0.0001 |

| 113 to <136 | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | 0.0002 | 1.09 (1.00–1.19) | 0.0150 |

| ≥136 | 1.07 (1.02–1.14) | 0.0010 | 1.22 (1.08–1.39) | <0.0001 |

| Chapter size | ||||

| 0 to <15 members | Ref. | — | Ref. | — |

| 15 to <25 members | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | <0.0001 | 1.03 (0.95–1.11) | 0.3398 |

| 25 to <35 members | 1.09 (1.05–1.13) | <0.0001 | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 0.0165 |

| 35 plus members | 1.14 (1.10–1.18) | <0.0001 | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 0.0207 |

| Chapter age | ||||

| <10 years | Ref. | — | Ref. | — |

| 10 to <20 years | 0.95 (0.92–0.99) | 0.0010 | 0.97 (0.90–1.05) | 0.2840 |

| 20 to <30 years | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | 0.0941 | 0.97 (0.89–1.05) | 0.2665 |

| 30 to <40 years | 0.97 (0.93–1.00) | 0.0155 | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) | 0.4226 |

| 40 plus years | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | <0.0001 | 0.94 (0.87–1.03) | 0.0742 |

ARR, adjusted relative risk.

For starting weight at 1 year, compared to the referent lowest starting weight (<80 kg), women with starting weights of 113 to <136 kg and ≥136 kg were more likely to have CSWL, whereas those with starting weights of 80 to <91 kg and 91 to <101 kg were not more likely to achieve CSWL than the referent group. For starting weight at 5 years, women with starting weights of 91 to <102, 102 to <113, and ≥136 kg were more likely to have CSWL, whereas those with starting weights of 80 to <91 kg and 113 to <136 kg were not more likely to achieve CSWL than the referent group.

For chapter size at 1 year, compared to the referent smallest chapter size category (<15 members), individuals in chapters with more members were more likely to achieve CSWL; however, at 5 years, there was no statistical difference in the risk for achieving CSWL between chapter size categories.

For chapter age at 1 and 5 years, individuals in older chapters were less likely to achieve CSWL, but this was only statistically significant at 1 year for those in chapters that had been in existence from 10 to <20, 30 to <40, and ≥40 years at 1 year.

Predictors for achieving CSWL: continuous variables

Table 3 shows the ARR results for the models with continuous variables at 1 and 5 years.

Table 3.

Adjusted Relative Risks for Factors Associated with Female Take Off Pounds Sensibly Participants Achieving Clinically Significant Weight Loss (≥5% Weight Loss) at the 1- and 5-Year Annual Renewals with Continuous Covariates

| 1-Year renewal | 5-Year renewal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARR (99% CI) | p | ARR (99% CI) | p | |

| Age (10 years) | 1.06 (1.05–1.07) | <0.0001 | 1.12 (1.09–1.15) | <0.0001 |

| Starting weight (20 kg) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | <0.0001 | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) | <0.0001 |

| Chapter size (15 members) | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <0.0001 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.002 |

| Chapter age (10 years) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.001 | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.33 |

The results using continuous variables were similar to those using the categorical variables. The ARR (99% CI) for a 20 kg increase in starting weight was 1.02 (1.01, 1.03); therefore, for every additional 20 kg in initial weight, individuals were 2% more likely to achieve CSWL (p < 0.001).

The ARR (99% CI) for a 10-year increase in starting age was 1.06 (1.05, 1.07); therefore, for every additional 10 years in age, participants were more than 6% more likely to achieve CSWL (p < 0.001).

The ARR (99% CI) for a 15-member increase in chapter size was 1.03 (1.02, 1.04); therefore, for every additional 15 members in a chapter, individuals were 3% more likely to achieve CSWL (p < 0.001).

Finally, the ARR (99% CI) for a 10-year increase in chapter age was 0.99 (0.98, 1.00); therefore, for every additional 10-year increase in chapter age, individuals were 1% less likely to achieve CSWL (p = 0.001). The results for the 5-year model are similar and are presented in Table 3.

All variables had a significant linear trend (at 1 year: p < 0.0001 for starting weight, starting age, and chapter size and p = 0.0003 for chapter age; at 5 years: p = 0.0006 for starting weight, p < 0.0001 for starting age, p = 0.004 for chapter size, and p = 0.04 for chapter age).

Discussion

At 1 year in this study, female TOPS participants were more likely to achieve CSWL if they were older, had a higher starting weight, and participated in a chapter that was less than 10 years old and had at least 15 members. At 5 years, the results were similar for participant age and starting weight, but the influence of chapter size and chapter age was mitigated.

Of the categories in the model, participant age had the largest influence on achieving CSWL, and older age was associated with more weight loss. This is similar to findings in the Weight Loss Maintenance (WLM) trial where participants aged 60 and older had greater weight loss, better weight maintenance, and a higher proportion of participants with ≥5% weight loss than their younger counterparts.13 Older participants in the DPP and one of its adaptations were also more successful than younger participants at achieving their weight loss goals.14 The Look AHEAD trial also found similar results among its older participants.12

Older women may be more successful at losing weight because they have fewer competing demands than younger women and can devote more time to weight loss efforts. For example, in both WLM and DPP, older participants attended more sessions during their weight loss phase and participated in more self-monitoring activities than the younger participants. The same may be true for older TOPS participants as well. In addition, while younger women may not have developed weight-related comorbidities, older individuals may be more motivated to lose weight because they have experienced the health consequences of excess weight, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

It is important to note that while older women may be more likely to achieve CSWL, weight loss in this population is controversial.17 Weight loss in all age ranges is associated with a loss of muscle and bone mass,18 and there is a concern that this may be more detrimental in older populations and increase physical frailty.19 However, physical frailty can improve with intentional weight loss (without an exercise component) despite a loss of muscle and bone mass;20 and muscle and bone loss associated with weight loss can be mitigated with an exercise component.20,21 Because TOPS recommends that participants gradually increase their activity to achieve the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines (150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise weekly) participants may lose less muscle and bone as a result of their weight loss.

The number of participants in each chapter was significantly associated with CSWL at 1 year. Women in chapters with 15 or more members were more likely to achieve CSWL than those in chapters with less than 15 members. This contradicts a study that found that individuals in smaller weight loss groups (12 members per group) lost more weight than those in a larger weight loss group (30 members per group) and with secondary analyses of one DPP adaptation and the Look AHEAD trial, which both found that weight loss was not associated with group size.22–24 Another study of a group intervention found that weight loss was negatively impacted by perceived conflict, low session attendance, and less self-monitoring, but not group size.25

There may be an optimal number of participants in weight loss groups to maximize individual performance. Chapters that are too small may not have enough individuals who participate on a regular basis for members to get the benefit of being in a group setting. Chapters that are too large may decrease the amount of time individuals participate in group activities. However, our results show that participants in larger chapters were more likely to achieve CSWL at 1 year. Therefore, other factors are likely involved as well. For example, group dynamics, including conflict and engagement, are probably influenced by individual personalities.

Starting weight was less strongly associated with achieving significant weight loss than participant age. At 1 year, those in the heaviest categories (113–136 and ≥136 kg) were more likely to achieve significant weight loss compared to the referent group. At 5 years, individuals in three of the five heavier weight loss categories were significantly more likely to achieve significant weight loss than the referent group. While heavier individuals are more likely to lose more weight than their lighter counterparts when measured in absolute terms, few studies compare initial weight and the percentage of weight loss. However, one small Canadian study of adults with BMI ≥27 kg/m2 and either metabolic syndrome or impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance found that heavier initial weight was a predictor for poor program retention and not achieving 5% weight loss at 1 year.26

Chapter age was associated with significant weight loss, where members of the youngest chapters (<10 years) were most likely to achieve CSWL. Data comparing decade-long weight loss groups are lacking. The LOOK Ahead study examined group for weight loss and adherence within groups, but all of those groups formed were compared at 1 year. Therefore, we can only hypothesize that engagement in the weight management process may be greater in newer chapters compared to older chapters.

This study has several limitations. First, this analysis did not include BMI. However, percentage weight change is an appropriate measure.

Second, these analyses only included those participants with recorded DOB who renewed their membership in the program. Since the results of our analysis regarding age are similar to other previous studies where age was available for all participants, we believe this limitation is of minimal impact. Furthermore, the median baseline weight was no different between those with and without a DOB; we do not believe that the groups were fundamentally different. However, we recognize that a higher percentage of people who included a DOB achieved CSWL than those who did not.

Third, the database provided only the number of people enrolled in each TOPS chapter for each year, but provided no information about the number of individuals who regularly participated in each chapter meeting. However, the categories describing the number of participants include ranges and we can infer that the participation of individuals would change randomly across chapters; therefore, the effects on the results might be mitigated.

Fourth, there were no available data on the number of sessions each individual attended or the level of adherence to behavior change recommendations, such as diet and physical activity.

Fifth, we have no data on the presence, improvement, or resolution of obesity-related comorbidities among participants who achieve CSWL. This is only minimally concerning because, if present, obesity-related comorbidities improve with weight loss of 5% or more of initial weight.

Finally, although we have previously published the results about the demographics of Census Tracts where TOPS chapters are located,15 we do not have race/ethnicity or socioeconomic data on individual participants because TOPS does not collect these data. Therefore, we do not know if the program would work equally well for women of different racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic groups.

Despite these limitations, this study is important. First, it uses a large real-world data set to determine the factors associated with CSWL in women and is generalizable to a broad population of women. Second, TOPS is a low-cost program with a national infrastructure that is accessible to many socioeconomic classes. Third, the obesity epidemic and its weight-related comorbidities are affecting older populations, and lifestyle modification programs can help treat these conditions.

Future studies should address the limitations noted above with a prospective evaluation of the TOPS program that could collect data on height; DOB; number of sessions attended; adherence to behavior change recommendations; presence of obesity-related comorbidities; race/ethnicity; and socioeconomic status. These studies can help determine if other variables are associated with achieving CSWL and if the program can be modified to help all women achieve CSWL equally. For example, while the initial age of participants cannot be changed, perhaps TOPS can be adapted to fit into the lifestyles of younger women.

Since the median baseline weight was no different between those with and without a DOB, we do not believe that the groups were fundamentally different. However, we recognize that a higher percentage of people who included a DOB achieved CSWL than those who did not. In addition, since more than half of the women in this analysis are aged 60 years or older, the program and its effect on obesity-related comorbidities should be evaluated prospectively to determine the efficacy and safety in this population as well.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge TOPS Club, Inc. for providing access to their data and Laura J. Helmkamp for providing additional analysis. Funding: The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number K01HL115599 to N.S.M., R01DK088105 to R.E.V.]. The sponsor was not involved in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing of the article; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. However, on January 29, 2016, Dr. Mitchell was asked to serve on the TOPS Research Advisory Committee. The purpose of the committee is to review any research grants received by TOPS and recommend approval, disapproval, or suggest modification to ensure that any proposed study is supportive of TOPS stated mission, acknowledges TOPS contribution, preserves integrity and confidentiality, and is not in conflict with other authorized research projects. This is a pro bono position, and, as part of the committee, Dr. Mitchell has reviewed three grants to date.

References

- 1.Thomas PR, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee to develop criteria for evaluating the outcomes of approaches to prevent and treat obesity. Weighing the options: criteria for evaluating weight-management programs. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein D. Beneficial health effects of modest weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1992;16:397–415 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vidal J. Updated review on the benefits of weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26 Suppl 4:S25–S28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1481–1486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation 2014;129:S102–S138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heshka S, Anderson J, Atkinson R, et al. Weight loss with self-help compared with a structured commercial program: A randomized trial. JAMA 2003;289:1792–1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell NS, Polsky S, Catenacci VA, Furniss AL, Prochazka AV. Up to 7 years of sustained weight loss for weight-loss program completers. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:248–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahern AL, Olson AD, Aston LM, Jebb SA. Weight Watchers on prescription: An observational study of weight change among adults referred to Weight Watchers by the NHS. BMC Public Health 2011;11:434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma J, Strub P, Xiao L, et al. Behavioral weight loss and physical activity intervention in obese adults with asthma. A randomized trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abildso CG, Zizzi S, Fitzpatrick SJ. Predictors of clinically significant weight loss and participant retention in an insurance-sponsored community-based weight management program. Health Promot Pract 2013;14:580–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greaves CJ, Sheppard KE, Abraham C, et al. Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Public Health 2011;11:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadden TA, Neiberg RH, Wing RR, et al. Four-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: Factors associated with long-term success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:1987–1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Svetkey LP, Clark JM, Funk K, et al. Greater weight loss with increasing age in the weight loss maintenance trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:39–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brokaw SM, Carpenedo D, Campbell P, et al. Effectiveness of an adapted diabetes prevention program lifestyle intervention in older and younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:1067–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell NS, Nassel AF, Thomas D. Reach of effective, nationally-available, low-cost, nonprofit weight loss program in medically underserved areas (MUAs). J Community Health 2015;40:1201–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:940–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waters DL, Ward AL, Villareal DT. Weight loss in obese adults 65 years and older: A review of the controversy. Exp Gerontol 2013;48:1054–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heymsfield SB, Gonzalez MC, Shen W, Redman L, Thomas D. Weight loss composition is one-fourth fat-free mass: A critical review and critique of this widely cited rule. Obes Rev 2014;15:310–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villareal DT, Apovian CM, Kushner RF, Klein S, Nutrition ASf, NAASO TeOS. Obesity in older adults: Technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society. Obes Res 2005;13:1849–1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villareal DT, Chode S, Parimi N, et al. Weight loss, exercise, or both and physical function in obese older adults. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1218–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beavers KM, Beavers DP, Nesbit BA, et al. Effect of an 18-month physical activity and weight loss intervention on body composition in overweight and obese older adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:325–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dutton GR, Nackers LM, Dubyak PJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing weight loss treatment delivered in large versus small groups. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2014;11:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brokaw SM, Arave D, Emerson DN, et al. Intensive lifestyle intervention goals can be achieved as effectively with large groups as with small groups. Prim Care Diabetes 2014;8:295–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wing RR, Leahey T, Jeffery R, et al. Do weight loss and adherence cluster within behavioral treatment groups? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:638–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nackers LM, Dubyak PJ, Lu X, Anton SD, Dutton GR, Perri MG. Group dynamics are associated with weight loss in the behavioral treatment of obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23:1563–1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong W, Langlois MF, Kamga-Ngandé C, Gagnon C, Brown C, Baillargeon JP. Predictors of success to weight-loss intervention program in individuals at high risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;90:147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]