Abstract

Background: Women with physical disabilities increasingly aspire to become pregnant and bear children. Limited information about the potential interaction of their disabling conditions with pregnancy and childbirth exists to guide these women and their clinicians.

Materials and Methods: The interview guide was created with questions on topics such as pregnancy complications and secondary conditions, the impact of prior surgeries, experiences with pain relief during labor, and the impact on women's independence and participation in life activities. Interviews were conducted by telephone with 25 women with physical disabilities. They were subsequently transcribed verbatim and analyzed by using Atlas TI.

Results: Women generally reported a relatively modest impact of disabling conditions on their pregnancies. Most women were satisfied with the mode of delivery, but they experienced challenges during the labor and delivery process. The women found that careful advanced planning was helpful in managing the impact of their disabling conditions. The involvement of clinicians with disability-related expertise was, in some cases, another factor that contributed to a positive outcome.

Conclusions: The importance of advanced planning and the utility of involving clinicians with disability-related expertise suggest that the use of integrated, interdisciplinary team approaches could promote quality care by facilitating improved planning and management. Additional clinical research is needed to provide women and their clinicians with more information on potential complications and options for labor and delivery.

Keywords: : disabilities, obstetrics, pregnancy, labor and delivery, health disparities, high-risk pregnancy

Introduction

Women with physical disabilities increasingly aspire to become pregnant and bear children.1–3 A 2008 study of women with spinal cord injury (SCI) found that 44% of the women desired pregnancy and 36% conceived after the injury.4,5 Women with disabilities pursue their desire to have children, despite a paucity of information available to them and to their clinicians about the potential interaction of their disabling conditions with pregnancy and childbirth.6,7 Although a body of literature about the interaction of physical disability and pregnancy is emerging, the potential issues that women and their clinicians may need to address during pregnancy and childbirth have by no means been exhaustively explored.1 The purpose of this study is to explore the potential impact of a women's physical disability on her health and function during pregnancy and on her experience of labor and delivery. This study addresses topics that have not been dealt with extensively regarding the interaction of women's disabling conditions with their pregnancies. These include the risk of developing secondary conditions or complications, the impact of prior surgeries, and pain relief during labor. It also explores the impact of the interaction of pregnancy and disability on women's level of independence and participation in life activities. To examine these interactions, we will rely on the perinatal framework for women with disabilities previously described by Mitra et al.,8 and data from semi-structured interviews with 25 mothers with physical disabilities in the United States.

Perinatal health framework for women with physical disabilities

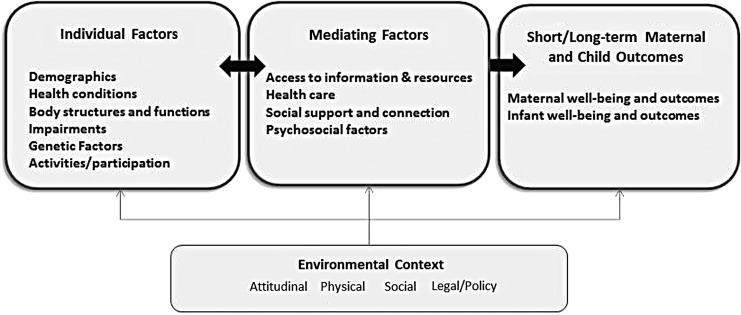

Mitra et al. have articulated a perinatal health framework that utilizes a life span perspective to explicate the multiple determinants of perinatal health specific to women with physical disabilities around the time of pregnancy.8 This framework builds on the efforts of authors such as Misra and also Evans and Stoddart to articulate a perinatal health framework for all women.9,10 It also builds on the work of Lu and Halfon, who applied a life course perspective to perinatal care among African American women.11 It further builds on the more disability-focused work of Nosek regarding reproductive health and the concepts articulated in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health articulated by the World Health Organization, which seeks to describe the impact of health conditions on participation in societal roles.12,13 Drawing on all of these frameworks, the perinatal health framework for women with physical disabilities divides the relevant variables into three categories: (1) individual factors, (2) mediating factors, and (3) short- and long-term maternal and child outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Perinatal Health Framework for Women with Physical Disabilities: Individual, Mediating, Maternal, and Infant Outcomes and Environmental Context

| Individual factors | Example |

|---|---|

| Demographic | Age |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Income | |

| Education | |

| Country of origin | |

| Marital status | |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Culture | |

| Health condition | Primary disabling condition |

| Comorbid conditions (e.g., asthma or diabetes) | |

| Secondary conditions (e.g., pressure ulcers, UTIs) | |

| Stability of condition | |

| Body structure and function | Structural anomalies (e.g., SCI, amputation) |

| Impairments | Limited mobility |

| Limited dexterity | |

| Genetic factors | Inheritable condition such as SMA, achondroplasia |

| Activities | Self-care, including dressing, bathing, eating (ADLs and IADLs) |

| Participation | Employment |

| Community and social interactions | |

| Intimate relationships | |

| Mediating factors | Example |

| Access to information and resources | Preconception counseling |

| Prenatal education | |

| Assistive technology | |

| Access to information on pregnancy | |

| Financial support | |

| Transportation access | |

| Access to nutrition | |

| Personal assistance with mothering tasks | |

| Healthcare-related factors | Physical, communication, programmatic, and attitudinal barriers to healthcare |

| Provider knowledge | |

| Health insurance status | |

| Reproductive care experiences | |

| Sexuality education | |

| Psychosocial factors | Women's knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about childbearing and motherhood |

| Self-efficacy | |

| Stress | |

| Depression/anxiety | |

| Risk for physical abuse | |

| Social support | Family support |

| Family and peer attitude toward pregnancy among women with physical disabilities | |

| Relationship with spouse/partner and peers | |

| Maternal and infant outcomes | Example |

| Maternal outcomes | Maternal health |

| Maternal well-being | |

| Maternal functioning | |

| Cesarean delivery | |

| Infant outcomes | Low birth weight |

| Preterm birth | |

| NICU admissions | |

| Congenital anomalies | |

| Clinical complications | |

| Maternal-infant bonding | |

| Environmental context | Example |

| Physical | Physical accessibility of woman's home and clinician's office |

| Accessibility of transportation | |

| Social | Opportunities for intimate relationships |

| Degree of social connectedness | |

| Attitudinal | Attitudes of broader community toward pregnancy among women with physical disabilities |

| Legal/policy | Americans with Disabilities Act |

| Social Security Act (Medicare, Medicaid, cash benefits) | |

| Affordable Care Act | |

| Maternal and child health policy |

ADLs, activities of daily living; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; SCI, spinal cord injury; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; UTIs, urinary tract infections.

For the purposes of this study, of particular importance among the individual factors are health conditions, which include the primary disabling condition along with comorbid conditions that could affect any woman (e.g., asthma or diabetes) and secondary conditions [e.g., urinary tract infections (UTIs)] to which a woman with a disability may already be susceptible, but the risk of which could be elevated during pregnancy. The stability of a woman's disabling condition may also be important. Body structure, including body functions and structural anomalies, may have an impact on the pregnancy, the mode of delivery, and the method of anesthesia that can be used.14 In some instances, a genetic condition may be passed on to the infant. Also of critical importance is the impact of these other factors on the woman's mobility, daily activities, participation in work, and other aspects of community life. The ultimate impact on maternal and infant outcomes is mediated by several factors, including access to information and resources, healthcare-related factors, psychosocial factors, and social support. An illustration of the framework can be found in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Illustration of perinatal health framework for women with physical disabilities.

Materials and Methods

Data were collected in the context of a larger mixed-methods study funded by the National Institutes of Health, which aims at systematically examining the health needs and barriers to care around the time of pregnancy for women with physical disabilities. The semi-structured interview guide was developed based on the literature and as a part of an iterative process involving the development of the perinatal framework for women with disabilities described by Mitra et al.8 We conducted 25 interviews with women with physical disabilities from across the United States. Interviews were conducted over the telephone to reach a national sample of participants.

To be eligible, the women must have had a physical disability or health condition that affected their ability to walk or to use their arms or hands at the time of their pregnancies. In addition, they must have delivered a child within the past 10 years, and be age 55 years or younger at the time of the interview. Information about the study was disseminated through a variety of methods, including email lists and social media of disability-related and local community-based organizations and social media of individuals.

Interviews took place in English over the phone, and participants received a $50 gift card as compensation. The interviews lasted a maximum of 2 hours and followed a semi-structured moderator's guide developed by the study's coinvestigators informed by the literature and a preliminary focus group. This study was originally approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School committee for the Protection of Human Subjects in Research on December 4, 2013, IRB ID No. H000120.

Analysis

Interview transcripts were content analyzed in an iterative, interpretive process. Codes were continuously revised and clarified by using a constant comparative method, as themes and patterns emerged.15 Women were asked about their disabling conditions and about the impact of these disabling conditions, if any, on their pregnancies and, conversely, whether the pregnancy impacted their disabling conditions and pre-pregnancy level of function. Women were also asked whether their infants were born full-term or premature and whether their pregnancies were planned. How each participant defined the term “planned” was left to their discretion. This content analysis was intended to be descriptive, not to generate theory. The investigators reviewed transcripts and identified an initial set of themes, which evolved into a codebook as additional transcripts were reviewed. One primary coder coded all the interviews and met repeatedly with the Principal Investigator throughout the coding process to discuss and clarify codes. A process for assessing reliability and consistency of coding across data was established based on Kurasaki's method, and a subsample of transcripts was examined for reliability.16 The data were analyzed by using Atlas TI.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the study participants. Nearly two-thirds of the women in this study were college graduates, and most of the rest had at least some college or vocational education after high school. The average age of the women at the time the youngest child was born was 32 years. Nearly half of the women had children between the ages of 5 and 10 years, whereas the others were equally distributed between younger age categories and two were currently pregnant. Fourteen participants had one child only, fifteen women had planned pregnancies, and 10 pregnancies were unplanned. Twenty had fathers present in the lives of their children, and five fathers were not present. Seven women had a child with a disability.

Table 2.

Mothers with Physical Disabilities: Sample Characteristics (at Time of Interview)

| Characteristics | No. |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| 21–25 | 4 |

| 26–30 | 8 |

| 31–35 | 9 |

| 36+ | 4 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 17 |

| African American/Black | 2 |

| Hispanic | 2 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Other | 3 |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 0 |

| High school grad | 2 |

| Some college or vocational education | 7 |

| Completed 4-year college degree | 11 |

| Postgraduate degree | 5 |

| Parity | |

| 1 | 14 |

| 2+ | 11 |

| Disabling condition | |

| Dwarfism | 5 |

| Muscular dystrophy/SMA (3) | 5 |

| OI | 4 |

| Cerebral palsy | 3 |

| Amputation | 2 |

| SCI | 2 |

| Stroke | 2 |

| Spina bifida | 1 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1 |

| Youngest child's age, years | |

| Under 1 | 6 |

| 1–3 | 4 |

| 3–5 | 4 |

| 5–10 | 11 |

| Child has disability | 7 |

| Assistive technology use | 18 |

OI, osteogenesis imperfecta.

The study participants reported a wide range of disabling conditions, including dwarfism, muscular dystrophy, osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), cerebral palsy, amputations, SCI, spina bifida, and multiple sclerosis. Eighteen of the women used some form of assistive technology to facilitate mobility, and seven ambulated independently.

Individual factors

Impact of disabling conditions on pregnancy

Despite concerns raised by clinicians, family members and experienced by the women themselves, the interviewees' pregnancies had positive outcomes and women generally reported a relatively modest impact of disabling conditions on their pregnancies. As one woman stated, “I think everyone around me had assumed that my pregnancy would just be—horrible and just this really painful and negative experience because of my disability and…that was really not the case.” Another typical comment was, “I felt like overall my pregnancy was so healthy and happy and I was just so glad to have that experience.”

The interaction of the disability and pregnancy was generally specific to each woman's underlying diagnosis. At times, it was difficult for women to identify whether a particular problem was disability related. For example, one woman with an SCI described back pain that she experienced and wondered aloud, “How much of that was a normal pregnancy, and how much of that was my disability making it difficult?”

More often, the women were able to identify instances in which the interaction of the disability and pregnancy created issues that needed to be addressed. One woman noted when describing the interaction between pregnancy and her own condition that, “There's a concern with SCI patients, and that is autonomic dysreflexia.” Another woman described how, “because of OI, I think it's called coxa vara,…I did have some significant hip pain from pretty early in the pregnancy.”

Nearly half of the women had a form of dwarfism, OI, or SMA, conditions that would make them substantially smaller in stature than the average woman and that often involved skeletal anomalies, such as scoliosis or anomalies of the hips. Most of the women with SMA and OI also reported concerns about respiratory insufficiency as the pregnancy progressed as did one of the five interviewees with dwarfism. As one woman explained, “respiratory distress is already associated with osteogenesis imperfecta” and so this concern was compounded during pregnancy. In addition, some participants, such as those with spinal cord injuries, were susceptible to secondary conditions such as UTIs. The UTIs that participants experienced were relatively minor and easily brought under control. None of the women reported getting pressure ulcers during pregnancy.

Most women did not report increased pain during pregnancy, but a couple did. For example, one woman with OI indicated that increased weight from the pregnancy caused her hips to spread, which she was told that her OI made more uncomfortable for her than it would be for other women. She said, “I felt like my hips were going to come out the sides.”

In some instances, the women reported that the pregnancy affected their activities. Some ambulatory participants reported that the pregnancy compromised their balance and some started using a wheelchair either part-time or full-time during pregnancy. One woman explained that she used a wheelchair “more when pregnant…because it threw me off balance and the extra weight is so hard to drag around.” Although many were able to maintain their pre-pregnancy level of independence, a few noted that they needed more assistance with activities of daily living. Husbands or significant others were often the primary source of assistance in these instances.

Only a few women reported being hospitalized during pregnancy. This occurred largely among the women with SMA and OI due to concerns about their respiratory status. A few women reported either working at home toward the end of their pregnancies or taking time off from work and staying on bedrest at home. One woman with an SCI reported that she stopped going to work because her growing abdomen prevented her from being able to lift her wheelchair into the car from the driver's side over her body and to put it on the passenger seat as she usually did. On the other hand, some participants worked up until the day before they were intended to deliver. Only a small number reported more typical complications of pregnancy, such as gestational diabetes or preeclampsia.

Some women reported a need for consultation with clinicians with expertise in their disabling conditions. For example, one woman reported a fairly extensive involvement of her pulmonologist to manage concerns with her lung capacity. Another noted the importance of involving a urologist in the planning and implementation of her cesarean section (C-section) due to previous urological surgery. One woman mentioned that she had a care coordinator who was instrumental in ensuring that she received proper care in the hospital.

Impact on labor and delivery

Disability definitely had an impact on the labor and delivery process. One woman echoed the sentiments of many, saying that even though the pregnancy went well, “the birth was a little bit challenging.” About three-quarters (18) of the participants had C-sections, and most of them were told that this was necessary due to their disabling condition. One woman with dwarfism commented that, “As a little person you don't have a choice. It's a C-section.”

The other women also seemed to feel that their C-sections were justified due to structural anomalies and other concerns. In several instances, the C-section was performed because the woman was advised that, although a vaginal birth might be possible, a C-section would be safer, as in the case of a woman who had experienced a stroke during a previous childbirth. She explained that, “A lot of women have strokes during childbirth, and so me being that I've already had one…they did not want me going into regular labor.” In a couple of instances, the C-section was performed for reasons having nothing to do with the disability, but rather for the reasons that C-sections are ordinarily performed, as in the case of one woman whose twins were breech.

Some women reported difficulties caused by prior disability-related surgeries. For example, one woman with spina bifida reported that previous urological surgery caused adhesions in her abdomen, complicating her C-section. She reported that her doctor told her that when she made the incision and saw the woman's internal organs, “it looked like someone had poured a jar of rubber cement in there.” Another woman reported that she needed a C-section due to previous surgery on her hips.

Some of the women who had vaginal births described needing assistance during that process. One woman with cerebral palsy described how she needed help holding her legs apart because she could not do it herself.

Women experienced numerous challenges with anesthesia due to their disabling conditions, previous surgeries, and clinician's lack of experience. One woman with an SCI above T6 had an epidural to prevent autonomic dysreflexia as a response to labor pain. Many of the women with scoliosis had spinal fusions and/or rods inserted in their backs and believed that this precluded an epidural. A typical comment was, “Because of my scoliosis and my spinal fusion, an epidural wasn't even an option.” A few women mentioned receiving early and fairly extensive consultations with an anesthesiologist, whereas others reported anesthesiologists being brought in late in the process, despite the implications of their disabilities and previous corrective surgeries for the correct method of administering anesthesia. One woman with significant orthopedic issues reported being told that, “There was no way to pinpoint who would be there when I delivered.… (They told me,) ‘We can handle it…When you come in to deliver, we'll figure it out then.’” Women reported highly variable responses from anesthesiologists in terms of their willingness and ability to perform an epidural or spinal block, which resulted in a substantial number of women having their babies under general anesthesia.

Mediating factors and maternal and infant outcomes

Despite the issues they faced with pregnancy and childbirth, all participants were glad that they had borne their children and most felt that overall their pregnancy was a positive experience. One woman captured the sentiments of many of the women when she said that her pregnancy was, “just a really joyful time.” A key factor in facilitating these positive outcomes was planning and management by both the women and their clinicians. The women went into the pregnancy experience expecting that they would have complications, and many of them did research on what to expect. A common comment was, “I did some of my own research, too and got in contact with some women that have the same disability as I do.” Several women made comments such as, “I kind of went into it with knowing it was not going to be a typical pregnancy.”

The data were examined to determine whether the quality of care may have improved or deteriorated over time, and no clear pattern emerged with respect to this question. We consistently found that the clinicians who the women found most helpful were those who put time and effort into anticipating complications and had strategies for addressing them. As one woman stated, “My OB was great. But I also think things only happened the way they happened because we planned ahead.” One of the strategies used was to involve other clinicians who might take part in the delivery, such as the anesthesiologist and the urologist, at an early stage to create relationships and facilitate the planning process.

Assistive technology such as mobility devices was also a mediating factor. Some women reported needing to use additional or different mobility aids during pregnancy. One amputee reported being unable to use her prosthetic leg due to swelling and needing to use a wheelchair during pregnancy. Two women reported that they were unable to use their wheelchairs because sitting upright was too uncomfortable. One described how, “I was so scrunched up that, when I was sitting upright, I couldn't breathe…(and) I was able to borrow a chair that lays down (reclines).”

Although recovery from childbirth was slow for some, most of the women reported that they were able to return to their previous level of health and function. Some women reported difficulties with losing weight after their children were born, and one or two of these noted that this did have an impact on their mobility. In addition, there was at least one woman who reported some degree of postpartum depression. One woman with cerebral palsy reported that she now had significant pain in her sacroiliac joint after having her third child and that her physician had told her that it was related both to her spasticity and to her three pregnancies. This pain caused her to use a scooter for mobility. Another woman reported that the doctor told her that her uterus had “come down,” a comment that suggests that perhaps that she was experiencing uterine prolapse. The doctor did not appear to think that the issue was urgent, however, and told her that “they would just staple it up next time.”

The babies born full-term were generally born healthy. Eleven women experienced a premature birth. Some of the women described the issues that arose for their premature infants in some detail. For example, one whose baby was born at thirty weeks noted that her baby, “had respiratory distress syndrome…because her lungs weren't fully developed. And she also had BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, which is the lungs are not making enough surfactant.” Another explained that, “He was four pounds, eight ounces. And he also got jaundice.” One of a pair of twins that was delivered breech and slightly premature had medical concerns commonly associated with a breech birth such as torticollis and issues with her hips, both of which were ultimately resolved successfully. Seven of the babies whose mothers had genetic conditions inherited their mother's disability.

Several of these premature births were experienced by women for whom short stature was a concern. Even so, a couple of these petite women were able to carry their babies to 37 weeks or more. And in some instances, the women indicated that they went into preterm labor for reasons unrelated to the disability as in the case of one woman who noted that, “All of the women in my family go into preterm labor.” Although some women were told by their clinicians that they would deliver as early as 24 or 26 weeks, the earliest that any interviewee delivered was 30 weeks and most of the women who delivered pre-term did so between 32 and 36 weeks.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to explore women's experiences of the impact of their physical disabilities on pregnancy and childbirth. The women in this study reported that their pregnancies had positive outcomes and were generally only modestly impacted by their disabling conditions. About half of the women interviewed had conditions such as dwarfism, OI, and SMA, which made them substantially smaller in stature than the average woman and often involved skeletal anomalies of the back or hips. Respiratory insufficiency during pregnancy was a significant concern for many of these women. Some women, for example, those with SCI were susceptible to secondary conditions such as UTIs, which women in this study reported to be relatively minor and easily brought under control. None of the women reported getting pressure ulcers during pregnancy, and only a couple of women reported experiencing increased pain. Only a few women reporting being hospitalized toward the end of their pregnancies, largely due to concerns about their respiratory status.

Some women reported that the pregnancy affected their activities. Some reported transitioning from being ambulatory to using a wheelchair either part-time or full-time during pregnancy. Although many were able to maintain their pre-pregnancy level of independence, a few women reported that, during pregnancy, they needed more assistance with activities of daily living, which was most often provided by spouses or partners.

Most of the women reported that their disabling conditions had at least some impact on labor and delivery. About three-quarters (18) of the participants had C-sections and most of them were told that this was advisable due to their disabling conditions, whereas a small number had C-sections for more typical reasons such as breech presentation. A small number of the women who had vaginal births reported needing additional assistance during that process. Several women reported challenges with pain relief due to their disabling conditions, previous surgeries, and clinician's lack of experience.

Women reported benefiting substantially from care that involved anticipation of potential secondary conditions and complications, combined with careful planning and management for addressing such issues during pregnancy, labor, and delivery as needed. The involvement of clinicians with expertise in various aspects of care related to the women's disability-specific needs was, in some cases, another factor that contributed to a positive outcome.

These findings underscore the importance of high-quality healthcare as a mediating factor that can lead to positive outcomes. In addition, the importance of advance planning and the utility of involving clinicians with disability-related expertise suggest that the use of integrated, interdisciplinary team approaches, such as those being more commonly used in the care of people with disabilities covered by Medicaid and Medicare, could promote quality care by facilitating improved planning.16–18 Although numerous studies have called for additional obstetric education and training in the perinatal care of women with disabilities,18–22 such training has been slow in coming and the use of interdisciplinary teams could help to compensate in gaps in obstetrical training by facilitating a better working relationship and exchange of knowledge between the obstetrician or nurse-midwife who is the expert in perinatal care and other clinicians whose specialty is focused on the disabling condition. It could also promote quality care by encouraging the involvement of anesthesiologists early in the process.23 Ideally, interdisciplinary teams would be engaged at the pre-conception stage, thereby maximally facilitating the planning process.1,18

Involvement of allied health professionals such as physical and occupational therapists in such interdisciplinary teams would help to address issues such as assistive technology, home modifications, and personal assistance, thereby assisting women in minimizing the challenges they face in caring for themselves during pregnancy and providing care to their infants afterward.1,19–21 Interdisciplinary teams could also assist women in addressing issues such as weight gain after pregnancy, a challenge for any new mother, but more of one for women with limited mobility. Reimbursement for such team arrangements needs to be sufficient to make it sustainable, and research to study how to make that possible is needed. The growing use of medical homes and new models of accountable care organizations that focus on quality of care as an outcome measure may provide opportunities for innovative approaches to interdisciplinary care.

Concerns have been raised about unnecessary C-sections among women with physical disabilities due to assumptions about the impact of their disabilities on their ability to give birth vaginally.22,24–26 The majority of the women in this study had a C-section, and many of them were told that this was necessary due to their disabling conditions. Our study was not structured to examine the appropriateness of C-section among women with different types of physical disabilities and, therefore, this study cannot be relied on as evidence on this issue. However, the high rate of C-sections among the interviewees was noteworthy.

The women generally enjoyed the experience of pregnancy and were happy with the outcomes. Careful planning and anticipation of potential secondary conditions and complications was key, and the use of interdisciplinary teams could facilitate such high-quality care.1,18,26,27 Also needed is additional diagnosis-specific clinical research to provide women and their clinicians with more information on potential complications and options for labor and delivery, such as the question of whether to perform a C-section or to facilitate a vaginal delivery and appropriate methods of pain relief.23–24,28–30

A limitation of this study is that the women interviewed were self-selected, which introduces the possibility of a selection bias toward those who felt good about their experiences with pregnancy and childbirth. Future research should explore ways to ensure that the voices of women with physical disabilities who had negative experiences with pregnancy and childbirth or who did not pursue their desire to have children for various reasons, including a lack of support from their clinicians, are heard. In addition, as indicated in Table 2, the nearly two-thirds of the women included in the sample were college graduates. Therefore, this study does not reflect the experiences of less educated women with disabilities who may encounter additional barriers to receiving good reproductive healthcare services. It is also important to bear in mind that this study reflects only the experiences of women with physical disabilities and cannot be interpreted to reflect the experiences of women with other types of disabilities, such as intellectual disabilities. Women were recruited by using social media, disability-related organizations, and community-based organizations, and they may likely be those who are well connected in the disability community. Therefore, the data may not reflect the perspectives of women who are less connected. The study sample was mostly White, and recruitment materials and interviews were all in English. Specific information about socioeconomic status was not collected. As is always the case with self-reports, the data represent women's own perceptions of their care and could not be validated against some objective norm. Because some of the women's pregnancies and childbirth experiences were as long as 10 years ago, it is possible that memories were skewed or distorted over time. However, the detailed nature of their stories lends credibility to their accounts.

Conclusions

More women with physical disabilities are aspiring to become mothers. Obstetrical clinicians can best support these women in achieving positive birth outcomes through careful advance planning and management and collaboration with other clinicians. Additional diagnosis-specific clinical research is needed to provide women and their clinicians with the information that is necessary to anticipate issues that may arise and facilitate planning. As Morton notes, “it is critical that women with disabilities and their physicians have access to the best available information when making decisions about childbearing to guide their decision making.”2 As increasing numbers of women with physical disabilities bear children, the importance of this knowledge will only increase over time.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Iezzoni LI, Wint AJ, Smeltzer SC, Ecker JL. Effects of disability on pregnancy experiences among women with impaired mobility. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015;94:133–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morton C, Le JT, Shahbandar L, Hammond C, Murphy EA, Kirschner KL. Pregnancy outcomes of women with physical disabilities: A matched cohort study. PM&R 2013;5:90–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smeltzer SC. Pregnancy in women with physical disabilities. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2007;36:88–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghidini A, Healey A, Andreani M, Simonson MR. Pregnancy and women with spinal cord injuries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87:1006–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malouf R, Redshaw M, Kurinczuk JJ, Gray R. Systematic review of heath care interventions to improve outcomes for women with disability and their family during pregnancy, birth and postnatal period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitra M, Long-Bellil LM, Iezzoni LI, Smeltzer SC, Smith LD. Pregnancy among women with physical disabilities: Unmet needs and recommendations on navigating pregnancy. Disabil Health J 2016;3:457–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertschy S, Geyh S, Pannek J, Meyer T. Perceived needs and experiences with healthcare services of women with spinal cord injury during pregnancy and childbirth—A qualitative content analysis of focus groups and individual interviews. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitra M, Long-Bellil LM, Smeltzer SC, Iezzoni LI. A perinatal health framework for women with physical disabilities. Disabil Health J 2015;8:499–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Misra DP, Guyer B, Allston A. Integrated perinatal health framework: A multiple determinants model with a life span approach. Am J Prev Med 2003;25:65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans RG, Stoddart GL. Producing health, consuming health care. Soc Sci Med 1990;31:1347–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu MC, Halfon N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: A life-course perspective. Matern Child health J 2003;7:13–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nosek MA, Young ME, Rintala DH, Howland CA, Foley CC, Bennett JL. Barriers to reproductive health maintenance among women with physical disabilities. J Womens Health 1995;4:505–518 [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirschner K, Gill C, Panko Reis J, Hammond C. Health issues for women with disabilities. In: DeLisa JA, Gans BM, Walsh NE, eds. Physical medicine and rehabilitation: Principles and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 2005:1562–1582 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurasaki KS. Intercoder reliability for validating conclusions drawn from open-ended interview data. Field Methods 2000;12:179–194 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Libersky J, Au M, Hamblin A. Using lessons from disease management and care management in building integrated care programs. Hamilton, NJ: Integrated Care Resource Center, 2014:6 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thierry JM. The importance of preconception care for women with disabilities. Matern Child Health J 2006;10:175–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nosek M, Howland C, Rintala D, Young M, Chanpong G. National study of women with physical disabilities: Final report. Sex Disab 2001;19:5–40 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker H, Stuifbergen A, Tinkle M. Reproductive health care experiences of women with physical disabilities: A qualitative study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:S26–S33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shulman R, Ellis J, Shore E, Kaplan FS, Badell M. Maternal genetic skeletal disorders: Lessons learned from cases of maternal osteogenesis imperfecta and fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Clin Gynecol Obstet 2015;4:184–187 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sterling L, Keunen J, Wigdor E, Sermer M, Maxwell C. Pregnancy outcomes in women with spinal cord lesions. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35:39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuczkowski KM. Labor analgesia for pregnant women with spina bifida: What does an obstetrician need to know? Arch Gynecol Obstet 2007;275:53–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson AB, Wadley V. A multicenter study of women's self-reported reproductive health after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999;80:1420–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarasoff LA. Experiences of women with physical disabilities during the perinatal period: A review of the literature and recommendations to improve care. Health Care Women Int 2015;36:88–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gajjar Dave F, Ansar H, Singhal T. PMM.77 Care of pregnant women with physical disabilities. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2014;99(Suppl 1):A147 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iezzoni LI, Yu J, Wint AJ, Smeltzer SC, Ecker JL. General health, health conditions, and current pregnancy among US women with and without chronic physical disabilities. Disabil Health J 2014;7:181–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Signore C, Spong CY, Krotoski D, Shinowara NL, Blackwell SC. Pregnancy in women with physical disabilities. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:935–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Argov Z, de Visser M. What we do not know about pregnancy in hereditary neuromuscular disorders. Neuromuscul Disord 2009;19:675–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson AB, Sipski ML. Reproductive issues for women with spina bifida. J Spin Cord Med. 2004;28:81–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]