Abstract

Purpose

The present review aimed to assess the role of exosomal miRNAs in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), normal fibroblasts (NFs), and cancer cells. The roles of exosomal miRNAs and miRNA dysregulation in CAF formation and activation were summarized.

Methods

All relevant publications were retrieved from the PubMed database, with key words such as CAFs, CAF, stromal fibroblasts, cancer-associated fibroblasts, miRNA, exosomal, exosome, and similar terms.

Results

Recent studies have revealed that CAFs, NFs, and cancer cells can secrete exosomal miRNAs to affect each other. Dysregulation of miRNAs and exosomal miRNAs influence the formation and activation of CAFs. Furthermore, miRNA dysregulation in CAFs is considered to be associated with a secretory phenotype change, tumor invasion, tumor migration and metastasis, drug resistance, and poor prognosis.

Conclusions

Finding of exosomal miRNA secretion provides novel insights into communication among CAFs, NFs, and cancer cells. MicroRNA dysregulation is also involved in the whole processes of CAF formation and function. Dysregulation of miRNAs in CAFs can affect the secretory phenotype of the latter cells.

Keywords: Cancer-associated fibroblasts, MiRNA, Exosome, Cancer, Mechanism

Background

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), a major class of small non-coding RNAs that mediate post-transcriptional gene silencing by binding to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) or open reading frames (ORFs) of target mRNAs, have been widely studied in various physiological and pathological processes [1, 2]. Similar to protein coding genes, most miRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II to form terminal and poly-adenylated RNA precursors or primary transcripts (pri-miRNAs) [3]. Stress-signals in cancer cells regulate the production of particular pri-miRNAs by controlling the functionality of certain transcription factors [4]. Established roles of miRNAs include the regulation of cell growth and tissue differentiation [5]. As both processes are dysregulated in cancer formation and development, miRNAs can participate in several processes of cancer, such as metastasis, tumorigenesis, and drug resistance [6–8]. Previous studies reported that miRNAs might serve as a tool for cancer diagnosis [9], and dysregulation of miRNA expression could be used for patient prognosis [10]. In recent years, with the progress witnessed in exosome assessment, use of miRNA as a biomarker or therapeutic tool in clinical practice has become a reality [11, 12].

The microenvironment consists of different types of normal cells, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, pericytes, immune cells, and local or bone marrow-derived stromal stem and progenitor cells, and the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM) [13]. Tumor microenvironment heterogeneity can influence tumorigenesis, invasion, metastasis, and the therapeutic response [14, 15]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are vital constituents of the tumor microenvironment, and their interactions with cancer cells play a major role in mediating the formation and activation of CAFs [16]. In a mouse model of pancreatic insulinoma, it was found that 20–40% of CAFs originate from the bone marrow [17, 18]. Meanwhile, recent data indicated that stimulation of the u-PA/u-PAR system contributes to CAF activation during multiple myeloma (MM) progression [19]. In addition, cancer development depends not only on malignant cancer cells, but also on CAF activation [20]. The crosstalk between cancer cells and CAFs is responsible for cancer cell proliferation, metastasis, invasion, and other critical oncological behaviors [21, 22]. CAFs necessitate targeted treatment, which improves anti-cancer therapy in vitro and animal experiments [23, 24].

Accumulating evidence suggests that miRNAs play a critical role not only in cancer cells but also in the tumor microenvironment [25]. The dysregulation of miRNAs and exosomal miRNAs can influence the crosstalk between cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment [26, 27].

This review focused on the bridging role that exosomal miRNAs play among CAFs, NFs, and cancer cells, exploring how exosomal miRNAs and miRNA dysregulation activate CAFs. We also demonstrated that miRNA dysregulation mediates functional changes in CAFs.

Exosomal miRNAs constitute a bridge among CAFs, NFs, and cancer cells

Previous studies demonstrated that CAFs and cancer cells regulate each other by secreting a variety of cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular matrix (ECM) [28–31]. However, the mechanism underlying the communication among CAFs, NFs, and cancer cells remains unclear. Recent extracellular vesicle assessments demonstrated that cancer cells communicate with the neighboring cells via soluble factors secreted into the extracellular space [32, 33]. Extracellular vesicles can be classified into three main types according to size and biogenesis: exosomes (30–100 nm), microvesicles (100–1000 nm), and oncosomes (1–10 μm) [34]. Each of these three vesicle types plays crucial roles in cancer biology, with vesicular transport, particularly ‘exosome’ mediated transport standing out [35–37].

Exosomes contain a great variety of bioactive molecules, including signal peptides, microRNAs, lipids, and DNA [38]. A recent study demonstrated that a number of Rab family proteins, including Rab27a and Rab27b, act as key regulators of the exosome secretion pathway [39]. Exosome biogenesis is a very tightly regulated process governed by multiple signaling molecules, and begins with receptor activation that is unique to each cell type [40]. In cancer, tumor cells aberrantly secrete large amounts of exosomes to transport paracrine signals or to contribute to tumor-environment interactions at a distance. Exosomal miRNAs were first identified in human serum, and have also been described in several biological fluids, including saliva, breast milk, and urine [41]. Therefore, EVs containing exosomal miRNAs can regulate tumorigenesis and cancer development by altering the vesicular content and supplying the tumor niche with molecules favoring the progression of oncogenic processes such as proliferation, invasion, cancer stem cell propagation, and even drug resistance [42]. Thus, exosomal miRNAs mediate cell to cell communication and play major roles in the crosstalk between cancer cells and the macro−/microenvironment [43, 44]. More importantly, miRNAs are stably transferred by exosomes [45]. MicroRNAs in plasma exosome can be stably stored under different conditions, indicating that exosomal miRNAs are potential biomarkers or therapeutic tools [46].

Exosomal miRNAs and miRNA dysregulation mediate CAF formation and activation

Studies assessing the origin and activation of CAFs have been performed for several years, but the available data remain insufficient. MicroRNAs are dysregulated in several types of cancers [47], modulating cancer proliferation and progression [48, 49]. Recent studies have gradually established connections among exosomal miRNAs, miRNA dysregulation, and CAF activation (Table 1).

Table 1.

MicroRNAs and exosomal miRNAs mediate CAF formation and activation

| Differentially expressed microRNAs | Cancer type | Mechanism | Cancer cell function change | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exosomal miR-155 | Pancreatic cancer | Down-regulation of its target TP53INP1 | Not mentioned | [50] |

| Exosomal miR-211 | Melanoma cancer | Inhibition of IGF2R, hyper-activating IGF1R/MAPK signaling. | Proliferation, motility, collagen contraction | [55] |

| Exosomal miR-21/−155/−146a/−148a and let-7 g | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [52] |

| Exosomal miR-133b | Prostate cancer | IL-6 stimulation of CAF released miR133b to active NF | Not mentioned | [54] |

| Exosomal miR-9 | Triple-negative breast cancer | Not mentioned | Migration and invasion | [53] |

| Down-regulated miR-1/−206 and up-regulated miR-31 | NSCLC | FOXO3a/VEGFA/CCL2 signaling | Migration, colony formation, TAMs recruitment, tumor growth, and angiogenesis | [56] |

| Down-regulated miR-31/−214 and up-regulated miR-155 | Ovarian cancer | miR-214 target CCL5 | Growth, invasion, motility | [57] |

| Up-regulated miR-210 | Prostate cancer | Overexpression of hypoxia-up-regulated miR-210 | EMT and angiogenesis | [62] |

| Up-regulated miR-21 | Human normal primary fibroblasts | MiR-21 binds to the 3’UTR of Smad7 mRNA and inhibits its translation to reduce the competition between TGFBR1; Smad 7 binds to Smad 2 and 3. | Not mentioned | [63] |

| Up-regulated miR-21 | Esophageal cancer | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [64] |

| Up-regulated miR-27a/b | Esophageal cancer | Not mentioned | Increased secretion of TGF-β leads to cisplatin resistance | [59] |

| UP-regulated miR-7 | Head and neck cancer | Not mentioned | MiR-7 down-regulates RASSF2, which decreases PAR-4 secretion from CAFs, enhancing cell proliferation and migration | [60] |

| Up-regulated miR-199a/−214 | Pancreatic cancer | Not mentioned | Migration and proliferation | [65] |

| Down-regulated miR-149 | Gastric cancer | MiR-149 inhibits the activation of fibroblasts by reducing IL-6 and EP2 expression |

EMT and stem-like properties | [66] |

| Up-regulated miR-409-3p/−409-5p | Prostate cancer | Not mentioned | Over-expressed miR-409 in NFs confers a CAF phenotype and leads to miR-409 release by extracellular vesicles to promote tumorigenesis and EMT | [84] |

| Down-regulated miR-200 s | Breast cancer | Down-regulated miR-200 s up-regulates fibronectin and lysyl oxidase | Migration, invasion, metastasis | [61] |

Exosomal miRNAs promote the formation and activation of CAFs

Previous studies demonstrated that pancreatic cancer cells secrete miR-155 to activate NFs. This phenomenon might be related to miR-155-mediated down-regulation of its target TP53INP1 [50]. An innovative study showed that melanoma cells release miR-211-containing melanosomes, which were subsequently taken up by NFs. MicroRNA-211 inhibits the tumor suppressor IGF2R, thereby hyper-activating the IGF1R/MAPK signaling pathway. This promotes CAF formation and melanoma lung metastasis [51]. Exosomes released by chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells induce a CAF-like phenotype in NFs; miR-21, miR-155, miR-146a, miR-148a, and let-7 g are the most abundant miRNAs in these exosomes. However, an in-depth study of these five miRNAs is pending [52].

A study of triple negative breast cancer revealed a CAF-like phenotype inducible by tumor cells through exosome-mediated delivery of miR-9. Interestingly, miR-9 is also released by NFs and transferred to tumor cells. Another study found that miR-9 stimulates tumor cell migration by reducing E-cadherin levels [53]. Doldi et al. [54] reported that IL-6-stimulated CAFs release miR-133b to support paracrine activation of NFs.

MicroRNA dysregulation mediates CAF formation and activation

As mentioned above, cancer cells and CAFs release exosomal miRNAs to promote CAF formation [50, 52–55]. Here, we focused on miRNA dysregulation in CAFs in association with their formation and activation.

Our recent study demonstrated that miR-1 and miR-206 down-regulation and miR-31 up-regulation in NFs induce a functional conversion into CAFs and promote the migration, colony formation, and tumor growth of cancer cells, as well as tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) recruitment. Further studies demonstrated that miRNAs reprogram NFs into CAFs by mediating FOXO3a/VEGFA/CCL2 signaling [56]. A similar study in ovarian cancer revealed that miR-214 and miR-31 down-regulation and miR-155 up-regulation induce a functional conversion of NFs into CAFs. This results in a large number of up-regulated genes, highly enriched in chemokines, similar to the gene expression profile of CAFs; the most up-regulated chemokine, CCL5, was found to be a direct target of miR-214 [57, 58].

Another study of esophageal cancer demonstrated that miR-27a/b mediates CAF formation, with increased production of TGF-β leading to cisplatin resistance [59]. It is well-known that over-expression of miR-7 in NFs induces a functional conversion of NFs into CAFs in head and neck cancer (HNC) by downregulating RASSF2, which consequently decreases PAR-4 secretion by CAFs, enhancing the proliferation and migration of the co-cultured cancer cells [60]. Similar findings indicated that NFs, with down-regulated miR-200 s, display traits of activated CAFs in breast cancer and induce cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis via fibronectin and lysyl oxidase up-regulation [61]. In prostate cancer, overexpression of hypoxia-induced miR-210 in young fibroblasts increases senescence-associated features and converts these cells into CAF-like cells, thereby promoting EMT in cancer cells [62].

MiR-21 binds to the 3’UTRs of Smad7 mRNA and inhibits its translation. To reduce the competitive binding with TGFBR, Smad7 binds to Smad2, Smad3. Over-expression of miR-21 or Smad7 depletion promotes CAF formation, even without TGF-β1 stimulation [63]. Another study of esophageal cancer also showed that miR-21 might activate NFs and convert them into CAFs [64]. In pancreatic cancer, over-expression of miR-199a and miR-214 is the major regulator of CAF activation, inducing cancer cell migration and proliferation [65]. MiR-149 is down-regulated in gastric cancer CAFs; it inhibits fibroblast activation by down-regulating IL-6. Further studies demonstrated that CAFs enhance EMT and stem-like properties in GC cells in a miR-149-IL-6-dependent manner; PTGER2 (subtype EP2) is also a potential target of miR-149. Helicobacter pylori infection potentially promotes the pro-tumor properties of stromal fibroblasts by silencing mmu-mir-149 and stimulating IL-6 production [66]. Interestingly, miR-409 expression in NFs confers a CAF phenotype and results in miR-409 release via extracellular vesicles to promote tumor induction and EMT [31].

The above findings suggested that cancer development depends not only on malignant tumor cells, but also on CAF activation.

CAF-secreted exosomal miRNAs affect the functions of cancer cells

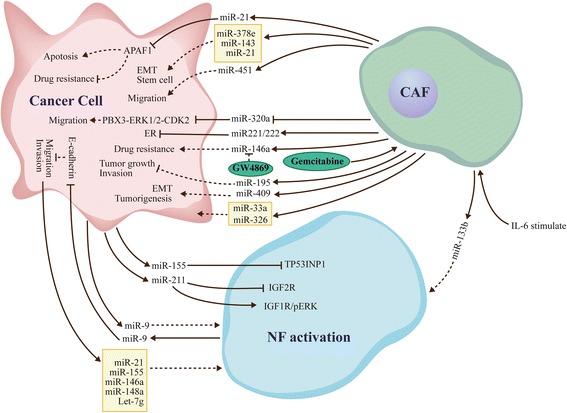

Previous findings demonstrated that exosomal miRNAs can be taken up by neighboring or distant cells, subsequently leading to changes in gene expression; this suggests a cell-specialized role in physiological and pathological conditions [67]. Here, we compiled the available literature with respect to exosomal miRNAs associations with the interactions among CAFs, NFs, and cancer cells (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Exosomal miRNAs mediate communication among CAFs, NFs, and cancer cells. Exosomal miRNAs mediate communication in the cell-micro environment and promote the formation of CAFs. Exosomal miRNAs secreted by CAFs and NFs impact migration, invasion, and metastasis in cancer cells, and dictate an aggressive cancer phenotype. Exosomal miRNAs modulate metabolism in cancer cells, and are closely related to drug resistance

Exosomal miRNAs and miRNA dysregulation lead to drug resistance

Drug resistance is a crucial factor affecting patient prognosis, and attracts increasing attention [68]. Although great efforts have been made to resolve the clinical issue of drug resistance, the underlying mechanism remains largely unclear [69]. Nevertheless, most studies proposed CAFs to be closely associated with chemoresistance acquisition and poor clinical prognosis [70, 71]. Dysregulation of miRNAs in CAFs and exosomal miRNA transfer between cancer cells and the microenvironment is correlated to chemoresistance regulation [72].

A recent study demonstrated that fibroblast-derived exosomes induce cancer stem cells that contribute to chemoresistance [73]. Furthermore, CAFs exposed to gemcitabine increase miR-146a and Snail secretion levels, a feature closely related to gemcitabine resistance. In addition, GW4869, an inhibitor of exosome release, significantly reduces survival in co-cultured epithelial cells [74], suggesting that drug-induced exosome miRNAs may be closely associated with drug resistance after treatment with chemotherapeutic agents. MiR-21 is a widely reported miRNA in several types of tumors. Interestingly, cancer cell-released exosomal miR21 promotes angiogenesis, and is involved in neoplastic processes [75, 76]. Moreover, exosomal miR-21 released by CAFs causes paclitaxel resistance by targeting APAF1 in ovarian cancer and decreasing apoptosis [77].

Dysregulation of miRNAs in CAFs results in drug resistance. The low expression of miR-1 induced CAFs causes high secretion levels of SDF-1α. Meanwhile, SDF-1α facilitates lung cancer cell proliferation and cisplatin resistance via CXCR4-activated NF-κB and Bcl-xL [78]. MicroR-27a/b over-expressed in CAFs can alter esophageal cancer cell sensitivity to cisplatin by increasing TGF-β release [59].

Altered exosomal miRNA profiles during drug administration demonstrates that drug resistance is a complex and dynamic process. In recent years, studies revealed that drug resistance is not only related to genomic or epigenomic changes, but also highly regulated by altered tumor cell metabolism [79]. Targeting the cancer stroma inhibits the metastatic outgrowth, indicating that interference with stromal reorganization might constitute a critical method to prevent recurrent transmitted diseases [80].

Exosomal miRNAs influence cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis

Exosomal miRNA-regulated cancer biology has been extensively assessed in recent years [81]. However, whether exosomal miRNAs released by CAFs affect cancer cells is relatively understudied. MiR-451, a tumor suppressor, is down-regulated in a variety of tumor types [82]. Conversely, a recent study found that CAFs use exosomal miR-451 as a signaling molecule to promote tumor cell migration and cancer progression [83]. This indicates that miRNA expression levels in tumor cells and CAFs might differ from those in exosomes. MiRNAs might therefore play different roles in cancer cells, CAFs, and exosomes.

Josson et al. [84] found that miR-409 up-regulation in NFs confers a CAF-like phenotype and results in miR-409 release by extracellular vesicles, promoting tumor induction and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). In esophageal cancer, miR-33a and miR-326 are mainly secreted by CAFs, although their functions remain undefined [85]. Interestingly, the antitumor miR-320a is reduced significantly in CAF-derived exosomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients (HCC). In addition, miR-320a suppresses HCC cell proliferation, migration, and metastasis, by binding to its direct downstream target PBX3 [86]. The miR-320a-PBX3 pathway inhibits the MAPK pathway, which induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and upregulates cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) and MMP2 expression in order to promote cell proliferation and metastasis [87].

MiR-195 released by CAFs reduces cancer cell growth and invasion; indeed, miR-195 loaded EVs in rat models of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) concentrate within the tumor, decrease tumor size, and improve survival in treated animals [88]. These findings suggested that miRNAs transported by exosomes might constitute a therapeutic tool for cancer treatment.

Exosomal microRNAs dictate an aggressive cancer phenotype

MiRNA dysregulation often indicates an invasive phenotype in several cancer types through different signaling pathways [89]. Shah et al. [90] demonstrated that CAF-secreted miR221/222 directly suppress ER expression, which is associated with ER-negative breast cancer. In addition, miR-21 and two other miRNAs (378e and 143) are increased in exosomes released from CAFs, and promote the aggressive ability of breast cancer cells, increasing stem cell amounts and inducing EMT [91]. Thus, CAFs strongly promote an aggressive cancer cell phenotype.

Exosomal miRNAs modulate cancer cell metabolism

Cancer metabolism alters tumorigenesis, which is vital for sustaining the proliferation and progression of cancer cells in order to support their escape from stringent regulation [92, 93]. Reducing cancer cell metabolism may be a new approach for cancer prevention and treatment [94]. It is known that the altered cancer metabolism is driven by genetic and epigenetic factors [95]. A recent study revealed that microenvironment-secreted exosomes can modulate cancer cell metabolism [96]. In addition, the available literature also confirmed that CAFs secreting exosomal miRNAs modulate cell metabolism in prostate and pancreatic cancers [97].

These findings indicate that exosomal miRNAs play a bridging role in ECM cross-talks, providing deep insights into the communication between CAFs and cancer cells. Thus, targeting circulating miRNAs might be an attractive therapeutic approach for cancer in the future.

MicroRNA dysregulation mediates functional changes in CAFs

In addition to exosomal miRNA association with interactions among CAFs, NFs, and cancer cells, miRNA dysregulation in CAFs mediates functional changes in CAFs. Most related reports demonstrated that dysregulated miRNAs are associated with tumor invasion, migration, proliferation, metastasis, and drug resistance. In addition, abnormal expression of miRNAs was found to be associated with poor prognosis, and could change the secretory phenotype of CAFs. The retrieved literature was sorted according to functional alterations.

MicroRNAs regulate the secretory phenotype of CAFs

As mentioned above, CAFs and cancer cells regulate each other by secreting a variety of cytokines, chemokines, and ECM proteins [28–31]. By altering the secretory phenotype of cancer cells or CAFs, the crosstalk between cancer cells and CAFs can be affected. Recent studies revealed that miRNA dysregulation plays a major role in controlling the secretory function of both cancer cells and CAFs [98]. For instance, miR-335 up-regulated in oral cancer CAFs increases the levels of COX-2 and PGE secreted by CAFs, inducing cancer cell motility by suppressing PTEN expression. MiR-335 is up-regulated by COX-2; conversely, COX-2 inhibition by celecoxib reduces miR-335 expression and restores PTEN production [99]. Similarly, miR-7 overexpression induces a functional conversion of NFs into CAFs through RASSF2 down-regulation, dramatically decreasing PAR-4 secretion from CAFs [60].

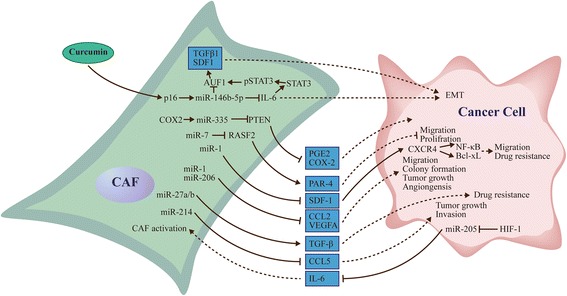

Another study demonstrated that p16 and miR-146b-5p are down-regulated in breast cancer CAFS; p16 restitution suppresses IL-6 expression and secretion by up-regulating miR-146b-5p in breast cancer [100]. Meanwhile, IL-6 in p16-defective cells is responsible for the paracrine pro-invasive/migratory effects of these cells on breast cancer. Down-regulation of p16 or miR-146b-5p induces a functional conversion of NFs into CAFs [101]. It was shown that curcumin induces p16 and miR-146b-5p, providing a potential treatment option for breast cancer [102]. Down-regulation of miR-1 and miR-206 and up-regulation of miR-31 in NFs induce a functional conversion into CAFs, with increased secretion of CCL2 and VEGFA. Of note, CCL2- and/or VEGFA-neutralizing antibodies administered to BALB/c athymic nude mice bearing pre-established lung tumors drastically reduce tumor growth, angiogenesis, TAM accumulation, and tumor metastasis [56]. Low expression of miR-1 is found in induced CAFs that secrete high levels of SDF-1α. Further studies found that SDF-1α promotes lung cancer cell proliferation and cisplatin resistance via CXCR4-activated NF-κB and Bcl-xL [78]. Similarly, miR-205 is the most down-regulated miRNA in prostate cancer cells as a result of CAF stimulation; miR-205 restitution reduces IL-6 secretion by cancer cells. Another study demonstrated that miR-205 is directly suppressed by HIF-1 [103]. As mentioned above, miR-27a/b mediates CAF formation and induces TGF-β release; in turn, TGF-β alters esophageal cancer sensitivity to cisplatin [59] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

MicroRNAs regulate the secretory phenotype of CAFs and cancer cells. MicroRNAs impact the cross-talk between CAF and cancer cells by modulating the secretory phenotype of CAFs and cancer cells

Metastasis

MiR-21, which appears several times in this review, is associated with the formation and activation of CAFs, and exosomal miR-21 released by CAFs can lead to paclitaxel resistance by targeting APAF1 in ovarian cancer [63, 64, 77, 91]. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, miR-21 is commonly associated with tumor metastasis and closely related to poor prognosis [104]. Clinicopathological findings confirmed that the stromal expression of miR-21 in colorectal cancer patients is closely related to distant metastasis [105].

As mentioned above, down-regulation of miR-200 s predicts a poor outcome in breast cancer patients via elevated expression of Fli-1 and TGF-β, contributing to ECM remodeling and triggering breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis both in vitro and in vivo [61].

Tumor migration and invasion

The crosstalk between the matrix and cancer cells determines whether cancer cells remain stable or become invasive and metastatic tumors [106]. MiR-106b is up-regulated in CAFs from gastric cancer, and promotes cell migration and invasion by up-regulating its target PTEN [107]. Conversely, miR-31 is reduced distinctly in endometrial cancer CAFs. Restitution of miR-31 could impair cell migration and invasion by directly targeting the homeobox gene SATB2, although cell proliferation is not affected [108]. In ER-positive breast cancer, miR-26b is downregulated in CAFs, leading to enhanced cell migration and invasion [109]. Meanwhile, miR-148a is down-regulated in endometrial cancer CAFs compared with matched NFs; miR-148a restitution directly targets WNT10B, significantly impairing the migration of cancer cells without affecting the growth rate [110]. Down-regulation of miR-148a is considered a marker of metastasis in several other tumors [111, 112]. Similarly, down-regulation of miR-15 and 16 in CAFs promotes prostate tumor proliferation and migration by reducing the post-transcriptional repression of Fgf-2 and its receptor Fgfr1 [113]. Moreover, CAFs and NFs regulate migration and invasion in cancer cells through secretory miRNAs [53, 83, 88].

MiRNAs and prognosis prediction

Identifying effective prognostic biomarkers is extremely challenging. Interestingly, miR-21 expression in CAFs is associated with decreased overall survival (OS) in pancreatic cancer patients administered 5-FU but not gemcitabine [114]. Naito et al. [115] showed that miR-143 is highly expressed in stromal fibroblasts of scirrhous type gastric cancer, in which it might promote tumor progression by regulating collagen type III through TGF-b/SMAD signaling; multivariate analysis revealed that miR-143 is an independent prognostic factor. A similar study demonstrated that miR-200a is down-regulated in NSCLC CAFs; miR-200a can also down-regulate its target gene hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and high miR-200a expression is predictive of good prognosis [116]. MicroR-106b expression in CAFs is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer [107].

Conclusion

This review summarized the recent research progress on exosome miRNAs in CAFs, NFs, and cancer cells, highlighting the complex roles of miRNAs in CAFs. First, cancer cells use exosomal miRNAs as signaling molecules to promote the formation of CAFs and modulate the functions of cancer cells. Secondly, miRNA dysregulation is closely related to CAF activation and formation, and affects the tumor-supportive capability of CAFs in vitro and in vivo.

Exosomal miRNAs released by NFs and CAFs can alter migration, invasion, and metastasis in cancer cells, and induce drug resistance. They dictate an aggressive cancer phenotype. MiR-451, a tumor suppressor, is down-regulated in a variety of tumor types; conversely, CAFs use exosomal miR-451 as a signaling molecule to promote tumor cell migration and cancer progression [83]. This also indicated that miRNA expression levels in cancer cells and CAFs might differ from those of exosomes. MicroRNAs may play different roles in cancer cells, CAFs, and exosomes. Exosomal miRNA level changes during drug use also suggest that drug resistance is a complex and dynamic process [74].

Using pre-miRNAs or anti-miRNA inhibitors to restitute the abnormal expression of miRNAs in CAFs can significantly inhibit cancer progression and proliferation in animal models [56]. MiR-195 released by CAFs reduces growth and invasion in cancer cells. Similarly, miR-195 loaded EVs suppress cancer cell proliferation, improving survival as assessed in animal models [88]. CAFs represent a promising target for future cancer therapy, and can resolve the issue of drug resistance. Moreover, injection of miRNAs and miRNA-loaded EVs should be further assessed for cancer treatment.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grants No BK20171484), the Project of Invigorating Health Care through Science, Technology and Education (Jiangsu Provincial Medical Youth Talent QNRC2016856) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (JX10231801).

Availability of data and materials

The material supporting the conclusion of this review has been included within the article.

Abbreviations

- APAF1

apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1

- CAFs

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

- CCL2

C-C motif chemokine ligand 2

- CCL5

C-C motif chemokine ligand 5

- CDK2

cyclin-dependent kinase 2

- COX2

cytochrome c oxidase subunit II

- CXCR4

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EMT

epithelial to mesenchymal transition

- ER

estrogen receptor

- EVs

extracellular vesicles

- FGF2

fibroblast growth factor 2

- FGFR1

fibroblast growth factor receptor 1

- FLI1

Fli-1 proto-oncogene

- Foxo3a

forkhead box O3A

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- HIF1

Hif1p

- HNC

head and neck cancer

- IGF1R

insulin like growth factor 1 receptor

- IGF2R

insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- MAPK

map kinase

- miRNAs

microRNAs

- MM

multiple myeloma

- MMP2

matrix metallopeptidase 2

- NFs

normal fibroblasts

- NSCLC

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

- P16

biomineralization protein SpP16

- PAWR (PAR4)

pro-apoptotic WT1 regulator

- PBX3

PBX homeobox 3

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- PTGER2

prostaglandin E receptor 2

- RASSF2

Ras association domain family member 2

- SATB2

SATB homeobox 2

- SMAD

SMAD family member

- TAMs

Tumor-associated macrophages

- TGF-β1

Transforming Growth Factor-β1

- TP53INP1

Tumor protein 53-induced nuclear protein-1

- UPA

urokinase

- UPAR

urokinase receptor

- VEGFA

vascular endothelial growth factor A

- WNT10B

Wnt family member 10B

Authors’ contributions

YS, HS and FY designed the research. FY and ZN drafted the manuscript. FY, HS and WL critically revised the manuscript. LM and CS discussed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Fengming Yang, Email: yfmdoctor@163.com.

Zhiqiang Ning, Email: nzq027@126.com.

Ling Ma, Email: 1017782680@qq.com.

Weitao Liu, Email: liuweitaoly@163.com.

Chuchu Shao, Email: s_chuchu@sina.com.

Yongqian Shu, Email: shuyongqian1998@163.com.

Hua Shen, Email: medshenhua@126.com.

References

- 1.Ambros V. microRNAs: tiny regulators with great potential. Cell. 2001;107:823–826. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00616-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendell JT. MicroRNAs: critical regulators of development, cellular physiology and malignancy. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1179–1184. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bajan S, Hutvagner G. Regulation of miRNA processing and miRNA mediated gene repression in cancer. Microrna. 2014;3:10–17. doi: 10.2174/2211536602666140110234046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dews M, Homayouni A, Yu D, Murphy D, Sevignani C, Wentzel E, Furth EE, Lee WM, Enders GH, Mendell JT, Thomas-Tikhonenko A. Augmentation of tumor angiogenesis by a Myc-activated microRNA cluster. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1060–1065. doi: 10.1038/ng1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasinski AL, Slack FJ. Epigenetics and genetics. MicroRNAs en route to the clinic: progress in validating and targeting microRNAs for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:849–864. doi: 10.1038/nrc3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng Y, Zhang X, Feng X, Fan X, Jin Z. The crosstalk between microRNAs and the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in cancer. Oncotarget. 2016; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Xiong G, Feng M, Yang G, Zheng S, Song X, Cao Z, You L, Zheng L, Hu Y, Zhang T, Zhao Y. The underlying mechanisms of non-coding RNAs in the chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Liang HQ, Wang RJ, Diao CF, Li JW, Su JL, Zhang S. The PTTG1-targeting miRNAs miR-329, miR-300, miR-381, and miR-655 inhibit pituitary tumor cell tumorigenesis and are involved in a p53/PTTG1 regulation feedback loop. Oncotarget. 2015;6:29413–29427. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martens-Uzunova ES, Jalava SE, Dits NF, van Leenders GJ, Moller S, Trapman J, Bangma CH, Litman T, Visakorpi T, Jenster G. Diagnostic and prognostic signatures from the small non-coding RNA transcriptome in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31:978–991. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbano R, Palumbo O, Pasculli B, Galasso M, Volinia S, D'Angelo V, Icolaro N, Coco M, Dimitri L, Graziano P, et al. A miRNA signature for defining aggressive phenotype and prognosis in gliomas. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed FE. miRNA as markers for the diagnostic screening of colon cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14:463–485. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2014.869479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saadatpour L, Fadaee E, Fadaei S, Nassiri MR, Mohammadi M, Mousavi SM, Goodarzi M, Verdi J, Mirzaei H. Glioblastoma: exosome and microRNA as novel diagnosis biomarkers. Cancer Gene Ther. 2016;23:415–418. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2016.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hui L, Chen Y. Tumor microenvironment: sanctuary of the devil. Cancer Lett. 2015;368:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung HY, Fattet L, Yang J. Molecular pathways: linking tumor microenvironment to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:962–968. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Y. Tumor microenvironment and cancer therapy resistance. Cancer Lett. 2016;380:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1423–1437. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Direkze NC, Hodivala-Dilke K, Jeffery R, Hunt T, Poulsom R, Oukrif D, Alison MR, Wright NA. Bone marrow contribution to tumor-associated myofibroblasts and fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8492–8495. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishii G, Sangai T, Oda T, Aoyagi Y, Hasebe T, Kanomata N, Endoh Y, Okumura C, Okuhara Y, Magae J, et al. Bone-marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the cancer-induced stromal reaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309:232–240. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01544-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciavarella S, Laurenzana A, De Summa S, Pilato B, Chilla A, Lacalamita R, Minoia C, Margheri F, Iacobazzi A, Rana A, et al. u-PAR expression in cancer associated fibroblast: new acquisitions in multiple myeloma progression. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:215. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3183-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueller MM, Fusenig NE. Friends or foes - bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:839–849. doi: 10.1038/nrc1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erdogan B, Webb DJ. Cancer-associated fibroblasts modulate growth factor signaling and extracellular matrix remodeling to regulate tumor metastasis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2017;45:229–236. doi: 10.1042/BST20160387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neri S, Ishii G, Hashimoto H, Kuwata T, Nagai K, Date H, Ochiai A. Podoplanin-expressing cancer-associated fibroblasts lead and enhance the local invasion of cancer cells in lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:784–796. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slany A, Bileck A, Muqaku B, Gerner C. Targeting breast cancer-associated fibroblasts to improve anti-cancer therapy. Breast. 2015;24:532–538. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tchou J, Conejo-Garcia J. Targeting the tumor stroma as a novel treatment strategy for breast cancer: shifting from the neoplastic cell-centric to a stroma-centric paradigm. Adv Pharmacol. 2012;65:45–61. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397927-8.00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eichmuller SB, Osen W, Mandelboim O, Seliger B. Immune modulatory microRNAs involved in tumor attack and tumor immune escape. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Lee J, Hong BS, Ryu HS, Lee HB, Lee M, Park IA, Kim J, Han W, Noh DY, Moon HG. Transition into inflammatory cancer-associated adipocytes in breast cancer microenvironment requires microRNA regulatory mechanism. PLoS One. 2017;12:e174126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Zhang S, Yao J, Lowery FJ, Zhang Q, Huang WC, Li P, Li M, Wang X, Zhang C, et al. Microenvironment-induced PTEN loss by exosomal microRNA primes brain metastasis outgrowth. Nature. 2015;527:100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature15376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J, Chen S, Wang W, Ning BF, Chen F, Shen W, Ding J, Chen W, Xie WF, Zhang X. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through chemokine-activated hedgehog and TGF-beta pathways. Cancer Lett. 2016;379:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoon N, Park MS, Shigemoto T, Peltier G, Lee RH. Activated human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells suppress metastatic features of MDA-MB-231 cells by secreting IFN-beta. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2191. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Delaunay T, Naeem R, Carey VJ, Richardson AL, Weinberg RA. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shifrin DJ, Demory BM, Coffey RJ, Tyska MJ. Extracellular vesicles: communication, coercion, and conditioning. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:1253–1259. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-08-0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma P, Pan Y, Li W, Sun C, Liu J, Xu T, Shu Y. Extracellular vesicles-mediated noncoding RNAs transfer in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:57. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0426-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyiadzis M, Whiteside TL. The emerging roles of tumor-derived exosomes in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2017;31(6):1259–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Julich-Haertel H, Urban SK, Krawczyk M, Willms A, Jankowski K, Patkowski W, Kruk B, Krasnodebski M, Ligocka J, Schwab R, et al. Cancer-associated circulating large extracellular vesicles in cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;67(2):282–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Minciacchi VR, Spinelli C, Reis-Sobreiro M, Cavallini L, You S, Zandian M, Li X, Chiarugi P, Adam RM, Posadas EM, et al. MYC mediates large oncosome-induced fibroblast reprogramming in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(9):2306–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Azmi AS, Bao B, Sarkar FH: Exosomes in cancer development, metastasis,and drug resistance: a comprehensive review. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013,32:623–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Ostrowski M, Carmo NB, Krumeich S, Fanget I, Raposo G, Savina A, Moita CF, Schauer K, Hume AN, Freitas RP, et al. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:19–30. doi: 10.1038/ncb2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keller S, Sanderson MP, Stoeck A, Altevogt P. Exosomes: from biogenesis and secretion to biological function. Immunol Lett. 2006;107:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montecalvo A, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, Stolz DB, Sullivan ML, Karlsson JM, Baty CJ, Gibson GA, Erdos G, Wang Z, et al. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood. 2012;119:756–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balaj L, Lessard R, Dai L, Cho YJ, Pomeroy SL, Breakefield XO, Skog J. Tumour microvesicles contain retrotransposon elements and amplified oncogene sequences. Nat Commun. 2011;2:180. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishida-Aoki N, Ochiya T. Interactions between cancer cells and normal cells via miRNAs in extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:1849–1861. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1811-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Javeed N, Mukhopadhyay D. Exosomes and their role in the micro−/macro-environment: a comprehensive review. J Biomed Res. 2016;30(0):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Zhu M, Huang Z, Zhu D, Zhou X, Shan X, Qi LW, Wu L, Cheng W, Zhu J, Zhang L, et al. A panel of microRNA signature in serum for colorectal cancer diagnosis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:17081–17091. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ge Q, Zhou Y, Lu J, Bai Y, Xie X. miRNA in plasma exosome is stable under different storage conditions. Molecules. 2014;19:1568–1575. doi: 10.3390/molecules19021568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halvorsen AR, Helland A, Gromov P, Wielenga VT, Talman MM, Brunner N, Sandhu V, Borresen-Dale AL, Gromova I, Haakensen VD. Profiling of microRNAs in tumor interstitial fluid of breast tumors - a novel resource to identify biomarkers for prognostic classification and detection of cancer. Mol Oncol. 2017;11:220–234. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lima CR, Gomes CC, Santos MF. Role of microRNAs in endocrine cancer metastasis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.O'Bryan S, Dong S, Mathis JM, Alahari SK. The roles of oncogenic miRNAs and their therapeutic importance in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pang W, Su J, Wang Y, Feng H, Dai X, Yuan Y, Chen X, Yao W. Pancreatic cancer-secreted miR-155 implicates in the conversion from normal fibroblasts to cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:1362–1369. doi: 10.1111/cas.12747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dror S, Sander L, Schwartz H, Sheinboim D, Barzilai A, Dishon Y, Apcher S, Golan T, Greenberger S, Barshack I, et al. Melanoma miRNA trafficking controls tumour primary niche formation. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:1006–1017. doi: 10.1038/ncb3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paggetti J, Haderk F, Seiffert M, Janji B, Distler U, Ammerlaan W, Kim YJ, Adam J, Lichter P, Solary E, et al. Exosomes released by chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells induce the transition of stromal cells into cancer-associated fibroblasts. Blood. 2015;126:1106–1117. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-618025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baroni S, Romero-Cordoba S, Plantamura I, Dugo M, D'Ippolito E, Cataldo A, Cosentino G, Angeloni V, Rossini A, Daidone MG, Iorio MV. Exosome-mediated delivery of miR-9 induces cancer-associated fibroblast-like properties in human breast fibroblasts. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2312. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doldi V, Callari M, Giannoni E, D'Aiuto F, Maffezzini M, Valdagni R, Chiarugi P, Gandellini P, Zaffaroni N. Integrated gene and miRNA expression analysis of prostate cancer associated fibroblasts supports a prominent role for interleukin-6 in fibroblast activation. Oncotarget. 2015;6:31441–31460. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garcia-Silva S, Peinado H. Melanosomes foster a tumour niche by activating CAFs. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:911–913. doi: 10.1038/ncb3404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen H, Yu X, Yang F, Zhang Z, Shen J, Sun J, Choksi S, Jitkaew S, Shu Y. Reprogramming of normal fibroblasts into cancer-associated fibroblasts by miRNAs-mediated CCL2/VEGFA signaling. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mitra AK, Zillhardt M, Hua Y, Tiwari P, Murmann AE, Peter ME, Lengyel E. MicroRNAs reprogram normal fibroblasts into cancer-associated fibroblasts in ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:1100–1108. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chou J, Werb Z. MicroRNAs play a big role in regulating ovarian cancer-associated fibroblasts and the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:1078–1080. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tanaka K, Miyata H, Sugimura K, Fukuda S, Kanemura T, Yamashita K, Miyazaki Y, Takahashi T, Kurokawa Y, Yamasaki M, et al. miR-27 is associated with chemoresistance in esophageal cancer through transformation of normal fibroblasts to cancer-associated fibroblasts. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:894–903. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen Z, Qin X, Yan M, Li R, Chen G, Zhang J, Chen W. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote cancer cell growth through a miR-7-RASSF2-PAR-4 axis in the tumor microenvironment. Oncotarget. 2017;8:1290–1303. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang X, Hou Y, Yang G, Wang X, Tang S, Du YE, Yang L, Yu T, Zhang H, Zhou M, et al. Stromal miR-200s contribute to breast cancer cell invasion through CAF activation and ECM remodeling. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:132–145. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taddei ML, Cavallini L, Comito G, Giannoni E, Folini M, Marini A, Gandellini P, Morandi A, Pintus G, Raspollini MR, et al. Senescent stroma promotes prostate cancer progression: the role of miR-210. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:1729–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li Q, Zhang D, Wang Y, Sun P, Hou X, Larner J, Xiong W, Mi J. MiR-21/Smad 7 signaling determines TGF-beta1-induced CAF formation. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2038. doi: 10.1038/srep02038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nouraee N, Van Roosbroeck K, Vasei M, Semnani S, Samaei NM, Naghshvar F, Omidi AA, Calin GA, Mowla SJ. Expression, tissue distribution and function of miR-21 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuninty PR, Bojmar L, Tjomsland V, Larsson M, Storm G, Ostman A, Sandstrom P, Prakash J. MicroRNA-199a and −214 as potential therapeutic targets in pancreatic stellate cells in pancreatic tumor. Oncotarget. 2016;7:16396–16408. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li P, Shan JX, Chen XH, Zhang D, Su LP, Huang XY, Yu BQ, Zhi QM, Li CL, Wang YQ, et al. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-149 in cancer-associated fibroblasts mediates prostaglandin E2/interleukin-6 signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Res. 2015;25:588–603. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bronisz A, Godlewski J, Chiocca EA. Extracellular vesicles and MicroRNAs: their role in Tumorigenicity and therapy for brain tumors. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;36:361–376. doi: 10.1007/s10571-015-0293-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Caetano-Pinto P, Jansen J, Assaraf YG, Masereeuw R. The importance of breast cancer resistance protein to the kidneys excretory function and chemotherapeutic resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2017;30:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang W, Meng Y, Liu N, Wen XF, Yang T. Insights into Chemoresistance of prostate cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11:1160–1170. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.11439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tao L, Huang G, Wang R, Pan Y, He Z, Chu X, Song H, Chen L. Cancer-associated fibroblasts treated with cisplatin facilitates chemoresistance of lung adenocarcinoma through IL-11/IL-11R/STAT3 signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38408. doi: 10.1038/srep38408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang H, Xie C, Yue J, Jiang Z, Zhou R, Xie R, Wang Y, Wu S. Cancer-associated fibroblasts mediated chemoresistance by a FOXO1/TGFbeta1 signaling loop in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2017;56:1150–1163. doi: 10.1002/mc.22581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Santos JC, Ribeiro ML, Sarian LO, Ortega MM, Derchain SF. Exosomes-mediate microRNAs transfer in breast cancer chemoresistance regulation. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6:2129–2139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu Y, Yan C, Mu L, Huang K, Li X, Tao D, Wu Y, Qin J. Fibroblast-derived exosomes contribute to Chemoresistance through priming cancer stem cells in colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e125625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Richards KE, Zeleniak AE, Fishel ML, Wu J, Littlepage LE, Hill R. Cancer-associated fibroblast exosomes regulate survival and proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene. 2017;36:1770–1778. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu Y, Luo F, Wang B, Li H, Xu Y, Liu X, Shi L, Lu X, Xu W, Lu L, et al. STAT3-regulated exosomal miR-21 promotes angiogenesis and is involved in neoplastic processes of transformed human bronchial epithelial cells. Cancer Lett. 2016;370:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang XF, Zhang XW, Hua RX, Du YQ, Huang MZ, Liu Y, Cheng YF, Guo WJ. Mel-18 negatively regulates stem cell-like properties through downregulation of miR-21 in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:63352–63361. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Au YC, Co NN, Tsuruga T, Yeung TL, Kwan SY, Leung CS, Li Y, Lu ES, Kwan K, Wong KK, et al. Exosomal transfer of stroma-derived miR21 confers paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer cells through targeting APAF1. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11150. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li J, Guan J, Long X, Wang Y, Xiang X. mir-1-mediated paracrine effect of cancer-associated fibroblasts on lung cancer cell proliferation and chemoresistance. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:3523–3531. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maiso P, Huynh D, Moschetta M, Sacco A, Aljawai Y, Mishima Y, Asara JM, Roccaro AM, Kimmelman AC, Ghobrial IM. Metabolic signature identifies novel targets for drug resistance in multiple myeloma. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2071–2082. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barkan D, Kleinman H, Simmons JL, Asmussen H, Kamaraju AK, Hoenorhoff MJ, Liu ZY, Costes SV, Cho EH, Lockett S, et al. Inhibition of metastatic outgrowth from single dormant tumor cells by targeting the cytoskeleton. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6241–6250. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wei F, Ma C, Zhou T, et al. Exosomes derived from gemcitabine-resistant cells transfer malignant phenotypic traits via delivery of miRNA-222-3p. Molecular cancer. 2017;16(1):132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Redova M, Poprach A, Nekvindova J, Iliev R, Radova L, Lakomy R, Svoboda M, Vyzula R, Slaby O. Circulating miR-378 and miR-451 in serum are potential biomarkers for renal cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2012;10:55. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Khazaei S, Nouraee N, Moradi A, Mowla SJ. A novel signaling role for miR-451 in esophageal tumor microenvironment and its contribution to tumor progression. Clin Transl Oncol. 2017;19:633–640. doi: 10.1007/s12094-016-1575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Josson S, Gururajan M, Sung SY, Hu P, Shao C, Zhau HE, Liu C, Lichterman J, Duan P, Li Q, et al. Stromal fibroblast-derived miR-409 promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and prostate tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2015;34:2690–2699. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nouraee N, Khazaei S, Vasei M, Razavipour SF, Sadeghizadeh M, Mowla SJ. MicroRNAs contribution in tumor microenvironment of esophageal cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2016;16:367–376. doi: 10.3233/CBM-160575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang Z, Li X, Sun W, Yue S, Yang J, Li J, Ma B, Wang J, Yang X, Pu M, et al. Loss of exosomal miR-320a from cancer-associated fibroblasts contributes to HCC proliferation and metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2017;397:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Han SY, Han HB, Tian XY, Sun H, Xue D, Zhao C, Jiang ST, He XR, Zheng WX, Wang J, et al. MicroRNA-33a-3p suppresses cell migration and invasion by directly targeting PBX3 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:42461–42473. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li L, Piontek K, Ishida M, Fausther M, Dranoff JA, Fu R, Mezey E, Gould SJ, Fordjour FK, Meltzer SJ, et al. Extracellular vesicles carry microRNA-195 to intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and improve survival in a rat model. Hepatology. 2017;65:501–514. doi: 10.1002/hep.28735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu YC, Chang JT, Liao CT, Kang CJ, Huang SF, Chen IH, Huang CC, Huang YC, Chen WH, Tsai CY, et al. OncomiR-196 promotes an invasive phenotype in oral cancer through the NME4-JNK-TIMP1-MMP signaling pathway. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:218. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shah SH, Miller P, Garcia-Contreras M, Ao Z, Machlin L, Issa E, El-Ashry D. Hierarchical paracrine interaction of breast cancer associated fibroblasts with cancer cells via hMAPK-microRNAs to drive ER-negative breast cancer phenotype. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16:1671–1681. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1071742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Donnarumma E, Fiore D, Nappa M, Roscigno G, Adamo A, Iaboni M, Russo V, Affinito A, Puoti I, Quintavalle C, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts release exosomal microRNAs that dictate an aggressive phenotype in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(12):19592–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Ghaffari P, Mardinoglu A, Nielsen J. Cancer metabolism: a modeling perspective. Front Physiol. 2015;6:382. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Perera RM, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic cancer metabolism: breaking it down to build it back up. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:1247–1261. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vander HM. Targeting cancer metabolism: a therapeutic window opens. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:671–684. doi: 10.1038/nrd3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhou W, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF. Cancer metabolism and mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Achreja A, Zhao H, Yang L, Yun TH, Marini J, Nagrath D. Exo-MFA - a 13C metabolic flux analysis framework to dissect tumor microenvironment-secreted exosome contributions towards cancer cell metabolism. Metab Eng. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.Zhao H, Yang L, Baddour J, Achreja A, Bernard V, Moss T, Marini JC, Tudawe T, Seviour EG, San LF, et al. Tumor microenvironment derived exosomes pleiotropically modulate cancer cell metabolism. elife. 2016;5:e10250. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hook LM, Grey F, Grabski R, Tirabassi R, Doyle T, Hancock M, Landais I, Jeng S, McWeeney S, Britt W, Nelson JA. Cytomegalovirus miRNAs target secretory pathway genes to facilitate formation of the virion assembly compartment and reduce cytokine secretion. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kabir TD, Leigh RJ, Tasena H, Mellone M, Coletta RD, Parkinson EK, Prime SS, Thomas GJ, Paterson IC, Zhou D, et al. A miR-335/COX-2/PTEN axis regulates the secretory phenotype of senescent cancer-associated fibroblasts. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8:1608–1635. doi: 10.18632/aging.100987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Al-Ansari MM, Aboussekhra A. miR-146b-5p mediates p16-dependent repression of IL-6 and suppresses paracrine procarcinogenic effects of breast stromal fibroblasts. Oncotarget. 2015;6:30006–30016. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Al-Ansari MM, Hendrayani SF, Shehata AI, Aboussekhra A. p16(INK4A) represses the paracrine tumor-promoting effects of breast stromal fibroblasts. Oncogene. 2013;32:2356–2364. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hendrayani SF, Al-Khalaf HH, Aboussekhra A. Curcumin triggers p16-dependent senescence in active breast cancer-associated fibroblasts and suppresses their paracrine procarcinogenic effects. Neoplasia. 2013;15:631–640. doi: 10.1593/neo.13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gandellini P, Giannoni E, Casamichele A, Taddei ML, Callari M, Piovan C, Valdagni R, Pierotti MA, Zaffaroni N, Chiarugi P. miR-205 hinders the malignant interplay between prostate cancer cells and associated fibroblasts. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1045–1059. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kadera BE, Li L, Toste PA, Wu N, Adams C, Dawson DW, Donahue TR. MicroRNA-21 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tumor-associated fibroblasts promotes metastasis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lee KS, Nam SK, Koh J, Kim DW, Kang SB, Choe G, Kim WH, Lee HS. Stromal expression of MicroRNA-21 in advanced colorectal cancer patients with distant metastases. J Pathol Transl Med. 2016;50:270–277. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2016.03.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Barkan D, El TL, Michalowski AM, Smith JA, Chu I, Davis AS, Webster JD, Hoover S, Simpson RM, Gauldie J, Green JE. Metastatic growth from dormant cells induced by a col-I-enriched fibrotic environment. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5706–5716. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yang TS, Yang XH, Chen X, Wang XD, Hua J, Zhou DL, Zhou B, Song ZS. MicroRNA-106b in cancer-associated fibroblasts from gastric cancer promotes cell migration and invasion by targeting PTEN. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:2162–2169. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Aprelikova O, Yu X, Palla J, Wei BR, John S, Yi M, Stephens R, Simpson RM, Risinger JI, Jazaeri A, Niederhuber J. The role of miR-31 and its target gene SATB2 in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4387–4398. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.21.13674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Verghese ET, Drury R, Green CA, Holliday DL, Lu X, Nash C, Speirs V, Thorne JL, Thygesen HH, Zougman A, et al. MiR-26b is down-regulated in carcinoma-associated fibroblasts from ER-positive breast cancers leading to enhanced cell migration and invasion. J Pathol. 2013;231:388–399. doi: 10.1002/path.4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Aprelikova O, Palla J, Hibler B, Yu X, Greer YE, Yi M, Stephens R, Maxwell GL, Jazaeri A, Risinger JI, et al. Silencing of miR-148a in cancer-associated fibroblasts results in WNT10B-mediated stimulation of tumor cell motility. Oncogene. 2013;32:3246–3253. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yan H, Dong X, Zhong X, Ye J, Zhou Y, Yang X, Shen J, Zhang J. Inhibitions of epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cells-like properties are involved in miR-148a-mediated anti-metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2014;53:960–969. doi: 10.1002/mc.22064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lujambio A, Calin GA, Villanueva A, Ropero S, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Blanco D, Montuenga LM, Rossi S, Nicoloso MS, Faller WJ, et al. A microRNA DNA methylation signature for human cancer metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13556–13561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803055105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Musumeci M, Coppola V, Addario A, Patrizii M, Maugeri-Sacca M, Memeo L, Colarossi C, Francescangeli F, Biffoni M, Collura D, et al. Control of tumor and microenvironment cross-talk by miR-15a and miR-16 in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:4231–4242. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Donahue TR, Nguyen AH, Moughan J, Li L, Tatishchev S, Toste P, Farrell JJ. Stromal microRNA-21 levels predict response to 5-fluorouracil in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:952–959. doi: 10.1002/jso.23750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Naito Y, Sakamoto N, Oue N, Yashiro M, Sentani K, Yanagihara K, Hirakawa K, Yasui W. MicroRNA-143 regulates collagen type III expression in stromal fibroblasts of scirrhous type gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:228–235. doi: 10.1111/cas.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen Y, Du M, Wang J, Xing P, Zhang Y, Li F, Lu X. MiRNA-200a expression is inverse correlation with hepatocyte growth factor expression in stromal fibroblasts and its high expression predicts a good prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:48432–48442. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The material supporting the conclusion of this review has been included within the article.