Abstract

Background

This systematic review was completed by the Exercise for People with Cancer Guideline Development Group, a group organized by Cancer Care Ontario’s Program in Evidence-Based Care (pebc). It provides background and guidance for clinicians with respect to exercise for people living with cancer in active and post treatment. It focuses on the benefits of specific types of exercise, pre-screening requirements for new referrals, safety concerns, and delivery models.

Methods

Using the pebc’s standardized approach, medline and embase were systematically searched for existing guidelines, systematic reviews, and primary literature.

Results

The search identified two guidelines, eighteen systematic reviews, and twenty-nine randomized controlled trials with relevance to the topic. The present review provides conclusions about the duration, frequency, and intensity of exercise appropriate for people living with cancer.

Conclusions

The evidence shows that exercise is safe and provides benefit in quality of life and in muscular and aerobic fitness for people with cancer both during and after treatment. The evidence is sufficient to support the promotion of exercise for adults with cancer, and some evidence supports the promotion of exercise in group or supervised settings and for a long period of time to improve quality of life and muscular and aerobic fitness. Exercise at moderate intensities could also be sustainable for longer periods and could encourage exercise to be continued over an individual’s lifetime. It is important that a pre-screening assessment be conducted to evaluate the effects of disease, treatments, and comorbidities.

Keywords: Exercise, systematic reviews

INTRODUCTION

The inclusion of exercise into an individual’s daily lifestyle is known to promote many health benefits; the same holds true for people with cancer. In addition to improving physical wellbeing, exercise can help in the management of treatment side effects, and its physiologic and psychological changes can drastically affect quality of life (qol).

The present systematic review explores the effects of exercise for people living with cancer with respect to qol, physical fitness, safety, adverse events or injuries, intensity levels, types of exercise, and delivery models. The exercise-specific recommendations are relevant for oncologists, exercise consultants, primary care providers, and other members of health care teams who work with people with cancer. Guidelines, systematic reviews, and primary literature are used as the evidence for the review, which was conducted for the purposes of preparing an evidence-based guideline by Cancer Care Ontario’s pebc in 2015.

METHODS

The pebc uses the methods of the practice guidelines development cycle1 to produce evidence-based and evidence-informed guidance documents. The process consists of conducting a systematic review, conducting a quality appraisal and interpretation of the evidence, drafting recommendations that undergo internal review, and conducting an external review.

Literature Search Strategy for Guidelines and Systematic Reviews

A search of medline, embase, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (January 2005 to October 2013; updated to January 2014) was conducted for published guidelines and systematic reviews. The search terms “exercise guideline” and “exercise and cancer” were used in searches of the Standards and Guidelines Evidence Directory of Cancer Guidelines, the U.S. National Guideline Clearinghouse, and the Canadian Medical Association Infobase for existing evidence-based guidelines. Additional guidelines relevant to the present study were found in a general Internet search using the Google search engine. The agree ii instrument2 was used to evaluate the quality of guidelines that had relevant objectives and research questions. The amstar tool3 served a similar purpose for relevant systematic reviews. Two Cochrane reviews that covered all randomized controlled trials (rcts) until 2011 were identified. A systematic review of the primary literature was therefore conducted to update the Cochrane reviews.

Literature Search Strategy for Primary Studies

A search for primary studies in medline (September 2011 to April, week 1, 2015) and embase (September 2011 to April, week 2, 2015) used the mesh headings “exercise.mp” and “neoplasms.mp.” To be included, studies had to be rcts published in the English language between 2011 and 2015. The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool4 was used to assess rcts.

Study Selection Criteria: RCTs

Articles were considered for inclusion according to their study design and relevance to the research questions. Studies were included if they were rcts that

■ considered adult individuals with cancer in active or post treatment,

■ considered the effects of an exercise regimen compared with usual care,

■ evaluated the outcomes of qol and aerobic capacity or muscular fitness,

■ used an exercise regimen that included repetitive aerobic or resistance exercises,

■ were not included in an identified systematic review,

■ were published in the English language (because of unavailability of translation services), and

■ were published in 2011 or later.

Studies were excluded if they

■ compared exercise regimens,

■ involved non-repetitive exercise regimens (that is, yoga),

■ were observational studies, or

■ evaluated outcomes other than qol or muscular or aerobic fitness.

Data Extraction and Assessment of Study Quality and Potential for Bias

Data extraction was conducted by one author (CZ) and was reviewed by a second independent individual using a data audit procedure. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The data extracted from each relevant article were the authors, publication year, study population, number of participants, treatment phase, intervention characteristics, qol scores, fitness measures, adherence, and adverse events. All extracted data and information were audited by an independent auditor.

RESULTS

Overall Literature Search Results

The literature included in the review were 2 of the 11 identified guidelines, 18 of the 84 identified systematic reviews, and 29 of the 405 identified rcts.

Synthesizing the Evidence

Because of the clinical heterogeneity of the studies (for example, disease types, treatment status), the nature of the interventions (varying types of exercises), and the outcomes assessed (varying measures), a meta-analysis was not possible.

Outcomes

QOL and Exercise During Active or Post Treatment

A systematic review of evidence published between 2005 and 2013 identified two guidelines, eighteen systematic reviews, and twenty-nine rcts that examined topics concerning exercise, such as safety, qol, aerobic and muscular fitness, delivery models, and types of exercise (Figure 1, Table i). Much of the evidence supports an improvement in qol and physical fitness for patients participating in the interventions.

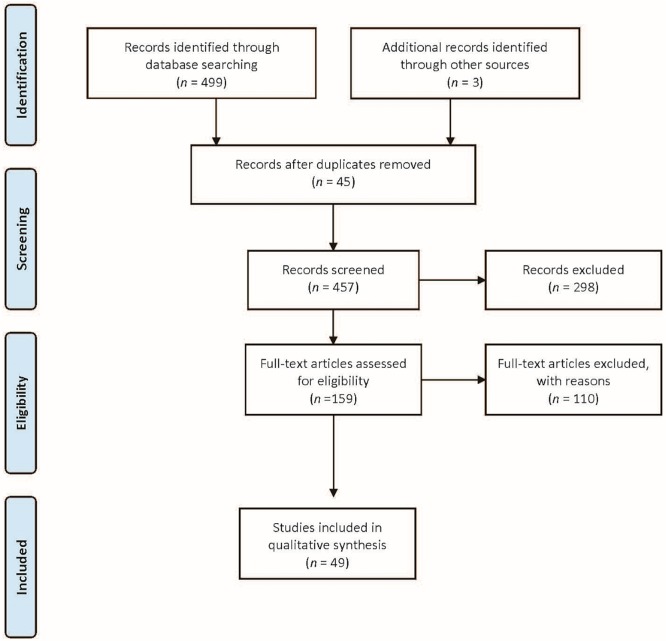

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

TABLE I.

Sources selected for inclusion

| Question (exercise compared with usual care) | Sources included (n) |

|---|---|

| Does exercise improve domains of QOL? | 1 Guideline5 |

| 16 Systematic reviews6–21 | |

| 21 RCTs22–42 | |

| Does exercise improve physical fitness (that is, strength, VO2 or aerobic capacity, objective measures of work done such as distance walked or sit-to-stand test)? | 16 Systematic reviews6–21 16 RCTs22,23,27,28,30,32,33,37,38,40,41,43–47 |

| What is the effect of exercise on people with cancer in terms of safety, adverse events, or injuries? | 2 Guidelines5,43 |

| 3 Systematic review6,7,20 | |

| 3 RCTs38,39,44 | |

| Are there differential results or outcomes for different intensity levels of aerobic compared with resistance types of exercise in people with cancer? | 1 Guideline43 |

| 7 Systematic reviews6,10,11,12,18,19,48 | |

| 12 RCTs22,26,29,31,33,35,39,40,42,45–47 | |

| What delivery models are appropriate for patients with different types or stages of cancer? | 4 Systematic reviews8,11,15,49 |

| 3 RCTs22,36,40 |

QOL = quality of life; RCT = randomized controlled trial; VO2 = the oxygen consumed during an activity.

The evidence is of moderate quality (Tables ii–iv). The guidelines scored well on the agree ii reporting instrument2. The systematic reviews had some issues with heterogeneity of outcomes, populations, and interventions. Issues with the rcts included active control groups who increased their voluntary exercise, variation in adherence rates or lack of adherence measurements, performance bias, and in some cases, use of questionnaires targeted to patients in active treatment that might not be applicable in a post-treatment population. The next few subsections examine evidence about the safety of exercise and whether, for people with cancer, exercise can be used as an intervention to improve qol as well as physical fitness—and, if so, what types of exercise accomplish that goal the best.

TABLE II.

AGREE II scores for the included guidelines

| Domain | Score (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| ACSM | KCE | |

| Scope and purpose | 72 | 94 |

| Stakeholder involvement | 50 | 58 |

| Rigour of domain | 52 | 81 |

| Clarity and presentation | 75 | 69 |

| Applicability | 31 | 4 |

| Editorial independence | 42 | 46 |

TABLE IV.

Risk-of-bias results for the included randomized controlled trials

| Reference | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcomes data | Selective reporting | Other | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arbane et al., 201137 | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Some loss to follow-up; no adherence | |

| Anderson et al., 201238 | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Single blinded | |

| Eakin et al., 201236 | Low | Unclear | High | High | High | Low | No information on pre-PA; all self-report data | |

| Saarto et al., 201240 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Both groups increased exercise the same amount | |

| Schmidt et al., 201250 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Small sample size | Usual care was gymnastics; small numbers, no adherence measure |

| Yeo et al., 201235 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | No information on randomization; not ITT; no info on pre-PA; no adherence measure | |

| Andersen et al., 201334 | Low | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | ||

| Broderick et al., 201347 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Small sample size | ||

| Cormie et al., 201345 | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Small sample size | |

| Cormie et al., 201339 | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Small sample size | |

| Courneya et al., 201333 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | ||

| Ergun et al., 201351 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Low | Small sample size | No information on pre-PA; no adherence measure |

| Hayes et al., 201332 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Low | Exercise group: 25% did not increase exercise | Personnel blinded for allocation or usual care group increased PA same amount as intervention group; no pre-PA |

| Lonbro et al., 201342 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Low | Control group some attrition | |

| Mitgaard et al., 201344 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | High | Low | Single blinded | High attrition |

| Pinto et al., 201346 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | High | Low | Personnel blinded for allocation | |

| Rogers et al., 201331 | Low | Low | High | High | High | Low | Pilot; small sample size | |

| Samuel et al., 201330 | Low | High | High | High | High | High | No information on pre-PA; no adherence measure | |

| Santa Mina et al., 201329 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Low power | |

| Stigt et al., 201328 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | High | Low | Low power | Lots of dropouts; no info on pre-PA; increase in pain |

| Arbane et al., 201427 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | ||

| Backman et al., 201426 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Low | High | All self-reported data | |

| Bourke et al., 201425 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Low | Single blinded | |

| Brocki et al., 201452 | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Loss to follow-up | |

| Galvao et al., 201441 | Low | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Control group received PA recommendations | |

| Oechsle et al., 201424 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Small sample size | |

| Porserud et al., 201453 | Low | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Low | Single blinded; small sample size | Lots of drop-outs |

| Cormie et al., 201523 | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Single blinded | No information on pre-PA; no follow-up |

| Winters-Stone et al., 201522 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | High | Low | Single blinded | Loss of follow-up; no info on pre-PA |

PA = physical activity; ITT = intention to treat.

TABLE III.

AMSTAR results for the included systematic reviews

| AMSTAR question | Reference | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Duijts et al., 20117 | Ferrer et al., 201111 | Jones et al., 201149 | McMillan and Newhouse, 201116 | Pastakia and Kumar, 201119 | van Haren et al., 201121 | Bauman et al., 20128 | Fong et al., 201213 | Keogh and MacLeod, 201215 | Mishra et al., 201218 (Active) | Mishra et al., 201217 (Post) | Steins Bisschop et al., 201220 | Cavalheri et al., 20139 | Focht et al., 201312 | Strasser et al., 201348 | Cramer et al., 201410 | Gardner et al., 201414 | ||

| 1. | Was an a priori design provided? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| 2. | Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? | Yes and no | Yes and no | Yes | Yes and no | Yes and no | Yes | Yes and no | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes and no | Yes | Yes |

| 3. | Was a comprehensive literature search performed? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4. | Was the status of publication (that is, grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion? | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| 5. | Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 6. | Were the characteristics of the included studies provided? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7. | Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? | Yes and no | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8. | Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 9. | Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t answer | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10. | Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 11. | Was the conflict of interest included? | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

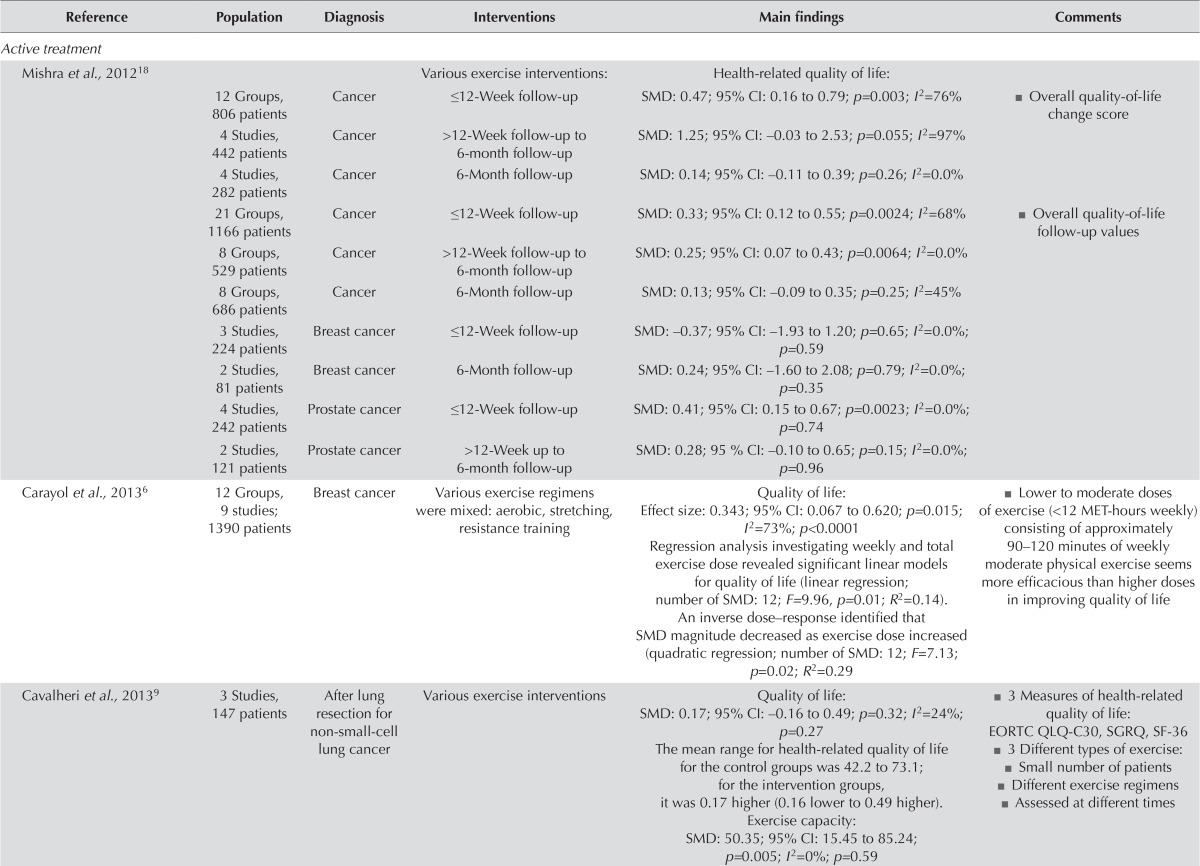

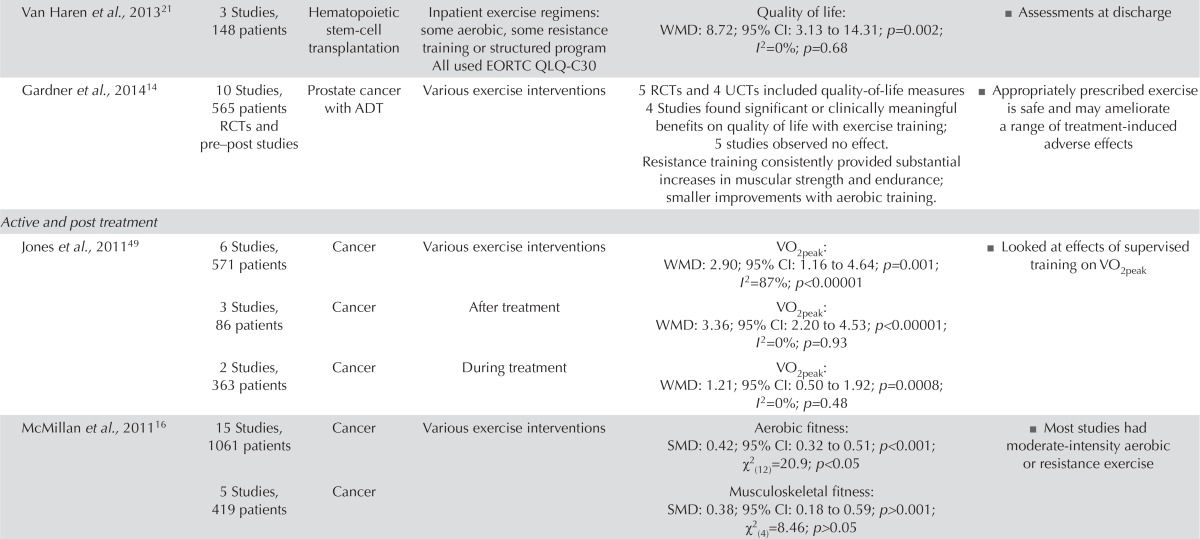

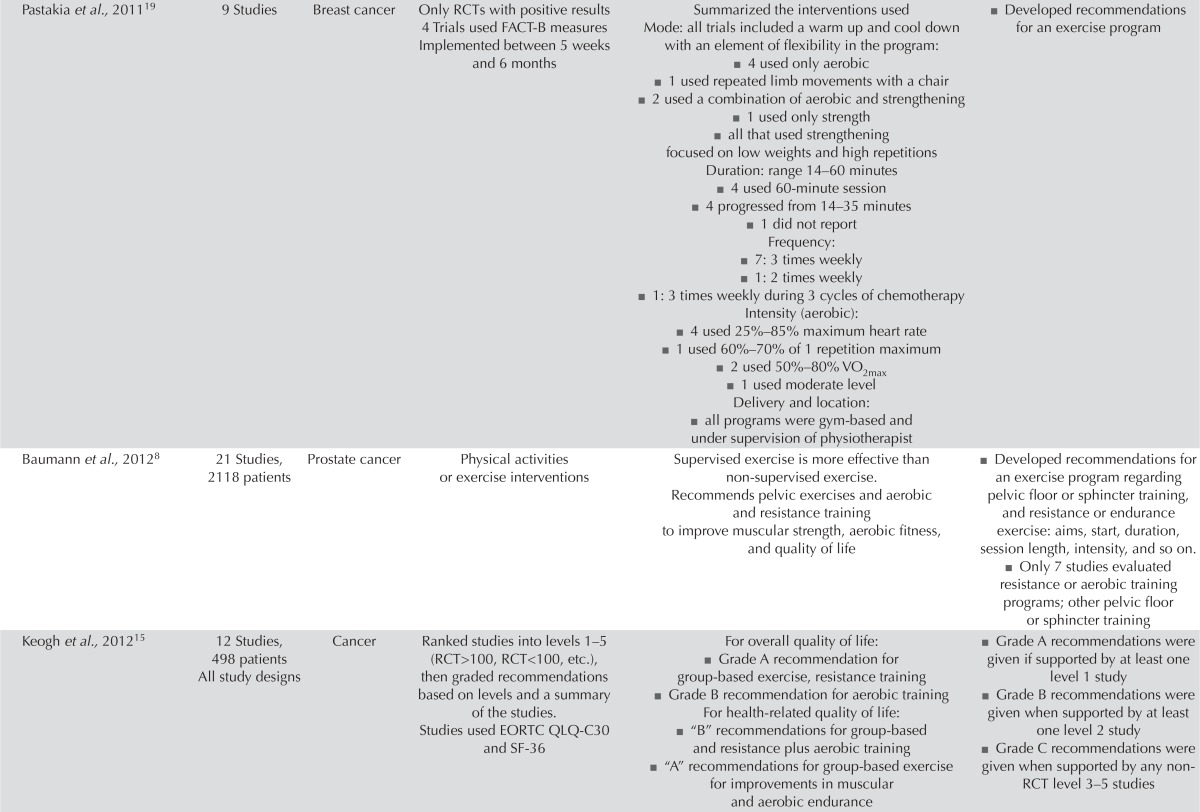

QOL and Muscular and Aerobic Fitness

For most cancer types, the Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre5 found no conclusive evidence about the benefits of exercise treatment for qol. Fourteen systematic reviews6–21 found an improvement in qol for people with cancer participating in an exercise intervention during the active treatment or post-treatment periods (Table v). Of the sixteen rcts involving patients in active treatment22–37, seven reported significant differences between the intervention and control groups (Table vi)23,24,26,31–33,36. In the thirteen post-treatment intervention studies38–53, two reported significant qol improvement in the exercise groups41,42. In particular, patients with lymphedema experienced qol benefits, and aerobic and resistance exercises were both safe for women who had undergone breast and axillary surgery6,7,38,39,44.

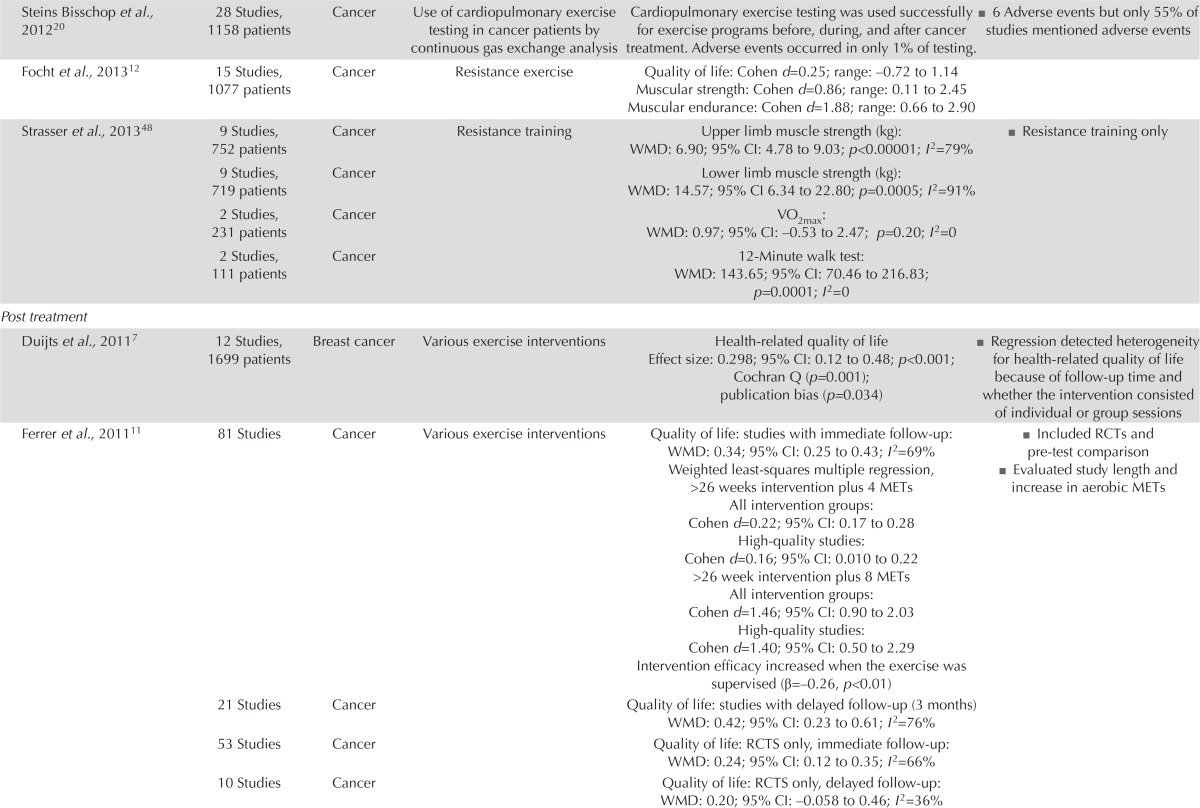

TABLE V.

Systematic review data

| Reference | Population | Diagnosis | Interventions | Main findings | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active treatment | |||||

| Mishra et al.,201218 | Various exercise interventions: | Health-related quality of life: | |||

| 12 Groups, 806 patients | Cancer | ≤12-Week follow-up | SMD: 0.47; 95% CI: 0.16 to 0.79; p=0.003; I2=76% | ■ Overall quality-of-life change score | |

| 4 Studies, 442 patients | Cancer | >12-Week follow-up to 6-month follow-up | SMD: 1.25; 95% CI: –0.03 to 2.53; p=0.055; I2=97% | ||

| 4 Studies, 282 patients | Cancer | 6-Month follow-up | SMD: 0.14; 95% CI: –0.11 to 0.39; p=0.26; I2=0.0% | ||

| 21 Groups, 1166 patients | Cancer | ≤12-Week follow-up | SMD: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.55; p=0.0024; I2=68% | ■ Overall quality-of-life follow-up values | |

| 8 Groups, 529 patients | Cancer | >12-Week follow-up to 6-month follow-up | SMD: 0.25; 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.43; p=0.0064; I2=0.0% | ||

| 8 Groups, 686 patients | Cancer | 6-Month follow-up | SMD: 0.13; 95% CI: –0.09 to 0.35; p=0.25; I2=45% | ||

| 3 Studies, 224 patients | Breast cancer | ≤12-Week follow-up | SMD: –0.37; 95% CI: –1.93 to 1.20; p=0.65; I2=0.0%; p=0.59 | ||

| 2 Studies, 81 patients | Breast cancer | 6-Month follow-up | SMD: 0.24; 95% CI: –1.60 to 2.08; p=0.79; I2=0.0%; p=0.35 | ||

| 4 Studies, 242 patients | Prostate cancer | ≤12-Week follow-up | SMD: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.67; p=0.0023; I2=0.0%; p=0.74 | ||

| 2 Studies, 121 patients | Prostate cancer | >12-Week up to 6-month follow-up | SMD: 0.28; 95 % CI: –0.10 to 0.65; p=0.15; I2=0.0%; p=0.96 | ||

| Carayol et al.,20136 | 12 Groups, 9 studies; 1390 patients | Breast cancer | Various exercise regimens were mixed: aerobic, stretching, resistance training | Quality of life: Effect size: 0.343; 95% CI: 0.067 to 0.620; p=0.015; of exercise (<12 MET-hours weekly) I2=73%; p<0.0001 Regression analysis investigating weekly and total exercise dose revealed significant linear models for quality of life (linear regression; number of SMD: 12; F=9.96, p=0.01; R2=0.14). An inverse dose–response identified that SMD magnitude decreased as exercise dose increased (quadratic regression; number of SMD: 12; F=7.13; p=0.02; R2=0.29 |

■ Lower to moderate doses consisting of approximately 90–120 minutes of weekly moderate physical exercise seems more efficacious than higher doses in improving quality of life |

| Cavalheri et al.,20139 | 3 Studies, 147 patients | After lung resection for non-small-cell lung cancer | Various exercise interventions | Quality of life: SMD: 0.17; 95% CI: –0.16 to 0.49; p=0.32; I2=24%; p=0.27 The mean range for health-related quality of life for the control groups was 42.2 to 73.1; for the intervention groups, it was 0.17 higher (0.16 lower to 0.49 higher). Exercise capacity: SMD: 50.35; 95% CI: 15.45 to 85.24; p=0.005; I2=0%; p=0.59 |

■ 3 Measures of health-related quality of life: EORTC QLQ-C30, SGRQ, SF-36 ■ 3 Different types of exercise: ■ Small number of patients ■ Different exercise regimens ■ Assessed at different times |

| Van Haren et al.,201321 | 3 Studies, 148 patients | Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation | Inpatient exercise regimens: some aerobic, some resistance training or structured program All used EORTC QLQ-C30 | Quality of life: WMD: 8.72; 95% CI: 3.13 to 14.31; p=0.002; I2=0%; p=0.68 | ■ Assessments at discharge |

| Gardner et al.,201414 | 10 Studies, 565 patients RCTs and pre–post studies | Prostate cancer with ADT | Various exercise interventions | 5 RCTs and 4 UCTs included quality-of-life measures 4 Studies found significant or clinically meaningful benefits on quality of life with exercise training; 5 studies observed no effect. Resistance training consistently provided substantial increases in muscular strength and endurance; smaller improvements with aerobic training. |

■ Appropriately prescribed exercise is safe and may ameliorate a range of treatment-induced adverse effects |

| Active and post treatment | |||||

| Jones et al.,201149 | 6 Studies, 571 patients | Cancer | Various exercise interventions | VO2peak: WMD: 2.90; 95% CI: 1.16 to 4.64; p=0.001; I2=87%; p<0.00001 | ■ Looked at effects of supervised training on VO2peak |

| 3 Studies, 86 patients | Cancer | After treatment | VO2peak: WMD: 3.36; 95% CI: 2.20 to 4.53; p<0.00001; I2=0%; p=0.93 | ||

| 2 Studies, 363 patients | Cancer | During treatment | VO2peak: WMD: 1.21; 95% CI: 0.50 to 1.92; p=0.0008; I2=0%; p=0.48 | ||

| McMillan et al.,201116 | 15 Studies, 1061 patients | Cancer | Various exercise interventions | Aerobic fitness: SMD: 0.42; 95% CI: 0.32 to 0.51; p<0.001; χ2 (12)=20.9; p<0.05 | ■ Most studies had moderate-intensity aerobic or resistance exercise |

| 5 Studies, 419 patients | Cancer | Musculoskeletal fitness: SMD: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.18 to 0.59; p>0.001; χ2 (4)=8.46; p>0.05 | |||

| Pastakia et al.,201119 | 9 Studies | Breast cancer | Only RCTs with positive results 4 Trials used FACT-B measures Implemented between 5 weeks and 6 months | Summarized the interventions used Mode: all trials included a warm up and cool down with an element of flexibility in the program: ■ 4 used only aerobic ■ 1 used repeated limb movements with a chair ■ 2 used a combination of aerobic and strengthening ■ 1 used only strength ■ all that used strengthening focused on low weights and high repetitions Duration: range 14–60 minutes ■ 4 used 60-minute session ■ 4 progressed from 14–35 minutes ■ 1 did not report Frequency: ■ 7: 3 times weekly ■ 1: 2 times weekly ■ 1: 3 times weekly during 3 cycles of chemotherapy Intensity (aerobic): ■ 4 used 25%–85% maximum heart rate ■ 1 used 60%–70% of 1 repetition maximum ■ 2 used 50%–80% VO2max ■ 1 used moderate level Delivery and location: ■ all programs were gym-based and under supervision of physiotherapist |

■ Developed recommendations for an exercise program |

| Baumann et al.,20128 | 21 Studies, 2118 patients | Prostate cancer | Physical activities or exercise interventions | Supervised exercise is more effective than non-supervised exercise. Recommends pelvic exercises and aerobic and resistance training to improve muscular strength, aerobic fitness, and quality of life |

■ Developed recommendations for an exercise program regarding pelvic floor or sphincter training, and resistance or endurance exercise: aims, start, duration, session length, intensity, and so on. ■ Only 7 studies evaluated resistance or aerobic training programs; other pelvic floor or sphincter training |

| Keogh et al.,201215 | 12 Studies, 498 patients All study designs | Cancer | Ranked studies into levels 1–5 (RCT>100, RCT<100, etc.), then graded recommendations based on levels and a summary of the studies. Studies used EORTC QLQ-C30 and SF-36 |

For overall quality of life: ■ Grade A recommendation for group-based exercise, resistance training ■ Grade B recommendation for aerobic training For health-related quality of life: ■ “B” recommendations for group-based and resistance plus aerobic training ■ “A” recommendations for group-based exercise for improvements in muscular and aerobic endurance |

■ Grade A recommendations were given if supported by at least one level 1 study ■ Grade B recommendations were given when supported by at least one level 2 study ■ Grade C recommendations were given when supported by any non-RCT level 3–5 studies |

| Steins Bisschop et al., 201220 | 28 Studies, 1158 patients | Cancer | Use of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in cancer patients by continuous gas exchange analysis | Cardiopulmonary exercise testing was used successfully for exercise programs before, during, and after cancer treatment. Adverse events occurred in only 1% of testing. | ■ 6 Adverse events but only 55% of studies mentioned adverse events |

| Focht et al.,201312 | 15 Studies, 1077 patients | Cancer | Resistance exercise | Quality of life: Cohen d=0.25; range: –0.72 to 1.14 Muscular strength: Cohen d=0.86; range: 0.11 to 2.45 Muscular endurance: Cohen d=1.88; range: 0.66 to 2.90 |

|

| Strasser et al.,201348 | 9 Studies, 752 patients | Cancer | Resistance training | Upper limb muscle strength (kg): WMD: 6.90; 95% CI: 4.78 to 9.03; p<0.00001; I2=79% | ■ Resistance training only |

| 9 Studies, 719 patients | Cancer | Lower limb muscle strength (kg): WMD: 14.57; 95% CI 6.34 to 22.80; p=0.0005; I2=91% | |||

| 2 Studies, 231 patients | Cancer | VO2max: WMD: 0.97; 95% CI: –0.53 to 2.47; p=0.20; I2=0 | |||

| 2 Studies, 111 patients | Cancer | 12-Minute walk test: WMD: 143.65; 95% CI: 70.46 to 216.83; p=0.0001; I2=0 | |||

| Post treatment | |||||

| Duijts et al.,20117 | 12 Studies, 1699 patients | Breast cancer | Various exercise interventions | Health-related quality of life Effect size: 0.298; 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.48; p<0.001; Cochran Q (p=0.001); publication bias (p=0.034) |

■ Regression detected heterogeneity for health-related quality of life because of follow-up time and whether the intervention consisted of individual or group sessions |

| Ferrer et al.,201111 | 81 Studies | Cancer | Various exercise interventions | Quality of life: studies with immediate follow-up: WMD: 0.34; 95% CI: 0.25 to 0.43; I2=69% Weighted least-squares multiple regression, >26 weeks intervention plus 4 METs All intervention groups: Cohen d=0.22; 95% CI: 0.17 to 0.28 High-quality studies: Cohen d=0.16; 95% CI: 0.010 to 0.22 >26 week intervention plus 8 METs All intervention groups: Cohen d=1.46; 95% CI: 0.90 to 2.03 High-quality studies: Cohen d=1.40; 95% CI: 0.50 to 2.29 Intervention efficacy increased when the exercise was supervised (β=–0.26, p<0.01) |

■ Included RCTs and pre-test comparison ■ Evaluated study length and increase in aerobic METs |

| 21 Studies | Cancer | Quality of life: studies with delayed follow-up (3 months) WMD: 0.42; 95% CI: 0.23 to 0.61; I2=76% | |||

| 53 Studies | Cancer | Quality of life: RCTS only, immediate follow-up: WMD: 0.24; 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.35; I2=66% | |||

| 10 Studies | Cancer | Quality of life: RCTS only, delayed follow-up: WMD: 0.20; 95% CI: –0.058 to 0.46; I2=36% | |||

| Mishra et al.,201217 | Various exercise interventions | Health-related quality of life: | |||

| 11 Studies, 826 patients | Cancer | ≤12-Week follow-up | SMD: 0.48; 95% CI: 0.16 to 0.81; p=0.0032; I2=78% | ■ Overall quality-of-life change score | |

| 3 Studies, 181 patients | Cancer | >12-Week follow-up to 6-month follow-up | SMD: 0.14; 95% CI: 0.38 to 0.66; p=0.61; I2=64% | ||

| 2 Studies, 115 patients | Cancer | 6-Month follow-up | SMD: 0.46; 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.84; p=0.014; I2=0.0% | ||

| 16 Studies, 760 patients | Cancer | ≤12-Week follow-up | SMD: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.24 to 0.74; p=0.00011; I2=62% | ■ Overall quality-of-life values | |

| 5 Studies, 353 patients | Cancer | >12-Week follow-up to 6-month follow-up | SMD: 0.11; 95% CI: –0.10 to 0.32; p=0.32; I2=0.0% | ||

| 2 Studies, 115 patients | 6-Month follow-up | SMD: 0.25; 95% CI: –0.12 to 0.62; p=0.18; I2=0.0% | |||

| 2 Studies, 205 patients | Breast cancer | ≤12-Week follow-up | SMD: –0.13; 95% CI: –0.41 to 0.14; p=0.34; I2=0.0%; p=0.36 | ||

| 1 Study, 52 patients | Breast cancer | >12-Week up to 6-month follow-up | SMD: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.41 to 1.57; p=0.00084 | ||

| 2 Studies, 110 patients | Breast cancer | 6-Month follow-up | SMD: 0.14; 95% CI: –0.24 to 0.51; p=0.47; I2=0.0%; p=0.57 | ||

| 1 Study, 93 patients | Colorectal cancer | >12-Week up to 6-month follow-up | SMD: –0.20; 95% CI: –2.10 to 1.70; p=0.84 | ||

| Fong et al.,201213 | 2 Studies, 692 patients | Various exercise interventions | Quality of life (SF-36 mental health): SMD: 2.4; 95% CI: 0.7 to 4.1; p=0.01; I2=0% | ■ 1 Study had 641 patients; the other had 51 patients | |

| 5 Studies, 147 patients | 6-Minute walk test: SMD: 29; 95% CI: 3 to 55; p=0.03; I2=20%, p=0.288 | ||||

| 7 Studies, 388 patients | VO2peak(mL/kg/min): SMD: 2.2; 95% CI: 1.0 to 3.4; p<0.01; I2=18%; p=0.29 | ||||

| 3 Studies, 401 patients | Bench press (kg): SMD: 6; 95% CI: 4 to 8; p<0.01; I2=54%; p=0.12 | ||||

| Leg press (kg): SMD: 19; 95% CI: 9 to 28; p<0.01; I2=71%; p=0.03 | |||||

| Cramer et al.,201410 | 3 Studies, 238 patients | Colorectal cancer | Various exercise interventions | Quality of life: SMD: 0.18; 95% CI: –0.39 to 0.76; p=0.53; I2=59%, p=0.08 Physical fitness: SMD: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.25 to 0.93; p<0.01; I2=0%; p=0.44 |

■ Adverse events not reported ■ All 3 studies used different treadmill test protocols |

SMD = standardized mean difference; CI = confidence interval; MET = metabolic equivalent of task; EORTC QLQ-C30 = European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire for cancer patients; SGRQ = St. George Respiratory Questionnaire; SF-36: Short Form Health Survey; WMD = weighed mean difference; RCT = randomized controlled trial; ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; UCT = uncontrolled trial; VO2 = volume of oxygen; FACT-B = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast.

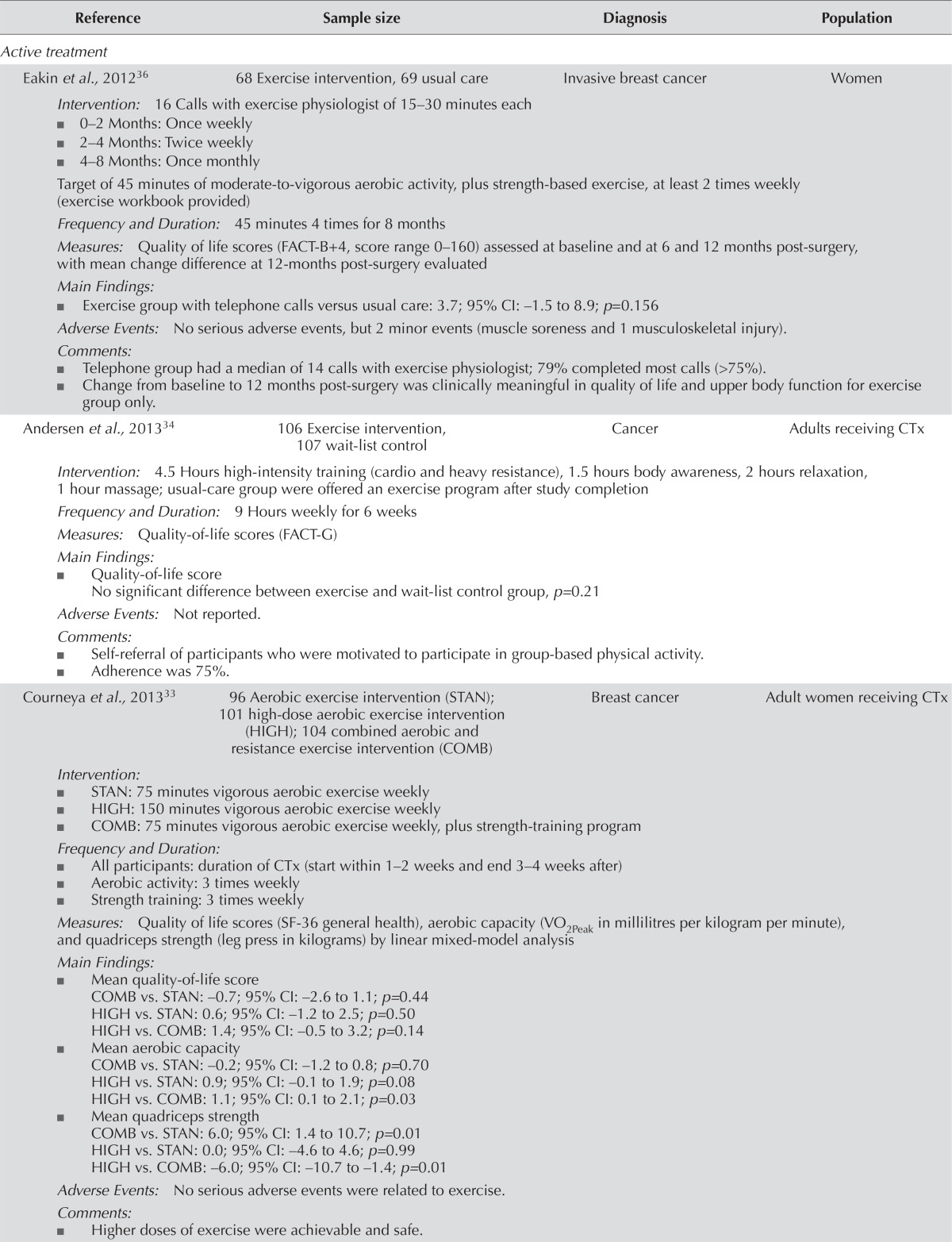

TABLE VI.

Randomized controlled trial data

| Reference | Sample size | Diagnosis | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active treatment | |||

| Eakin et al., 201236 | 68 Exercise intervention, 69 usual care | Invasive breast cancer | Women |

| Intervention: 16 Calls with exercise physiologist of 15–30 minutes each | |||

| ■ 0–2 Months: Once weekly | |||

| ■ 2–4 Months: Twice weekly | |||

| ■ 4–8 Months: Once monthly | |||

| Target of 45 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous aerobic activity, plus strength-based exercise, at least 2 times weekly (exercise workbook provided) | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 45 minutes 4 times for 8 months | |||

| Measures: Quality of life scores (FACT-B+4, score range 0–160) assessed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months post-surgery, with mean change difference at 12-months post-surgery evaluated | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Exercise group with telephone calls versus usual care: 3.7; 95% CI: −1.5 to 8.9; p=0.156 | |||

| Adverse Events: No serious adverse events, but 2 minor events (muscle soreness and 1 musculoskeletal injury). | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Telephone group had a median of 14 calls with exercise physiologist; 79% completed most calls (>75%). | |||

| ■ Change from baseline to 12 months post-surgery was clinically meaningful in quality of life and upper body function for exercise group only. | |||

| Andersen et al., 201334 | 106 Exercise intervention, 107 wait-list control | Cancer | Adults receiving CTx |

| Intervention: 4.5 Hours high-intensity training (cardio and heavy resistance), 1.5 hours body awareness, 2 hours relaxation, 1 hour massage; usual-care group were offered an exercise program after study completion | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 9 Hours weekly for 6 weeks | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (FACT-G) | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| No significant difference between exercise and wait-list control group, p=0.21 | |||

| Adverse Events: Not reported. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Self-referral of participants who were motivated to participate in group-based physical activity. | |||

| ■ Adherence was 75%. | |||

| Courneya et al., 201333 | 96 Aerobic exercise intervention (STAN); 101 high-dose aerobic exercise intervention (HIGH); 104 combined aerobic and resistance exercise intervention (COMB) | Breast cancer | Adult women receiving CTx |

| Intervention: | |||

| ■ STAN: 75 minutes vigorous aerobic exercise weekly | |||

| ■ HIGH: 150 minutes vigorous aerobic exercise weekly | |||

| ■ COMB: 75 minutes vigorous aerobic exercise weekly, plus strength-training program | |||

| Frequency and Duration: | |||

| ■ All participants: duration of CTx (start within 1–2 weeks and end 3–4 weeks after) | |||

| ■ Aerobic activity: 3 times weekly | |||

| ■ Strength training: 3 times weekly | |||

| Measures: Quality of life scores (SF-36 general health), aerobic capacity (VO2Peak in millilitres per kilogram per minute), and quadriceps strength (leg press in kilograms) by linear mixed-model analysis | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Mean quality-of-life score | |||

| COMB vs. STAN: −0.7; 95% CI: −2.6 to 1.1; p=0.44 | |||

| HIGH vs. STAN: 0.6; 95% CI: −1.2 to 2.5; p=0.50 | |||

| HIGH vs. COMB: 1.4; 95% CI: −0.5 to 3.2; p=0.14 | |||

| ■ Mean aerobic capacity | |||

| COMB vs. STAN: −0.2; 95% CI: −1.2 to 0.8; p=0.70 | |||

| HIGH vs. STAN: 0.9; 95% CI: −0.1 to 1.9; p=0.08 | |||

| HIGH vs. COMB: 1.1; 95% CI: 0.1 to 2.1; p=0.03 | |||

| ■ Mean quadriceps strength | |||

| COMB vs. STAN: 6.0; 95% CI: 1.4 to 10.7; p=0.01 | |||

| HIGH vs. STAN: 0.0; 95% CI: −4.6 to 4.6; p=0.99 | |||

| HIGH vs. COMB: −6.0; 95% CI: −10.7 to −1.4; p=0.01 | |||

| Adverse Events: No serious adverse events were related to exercise. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Higher doses of exercise were achievable and safe. | |||

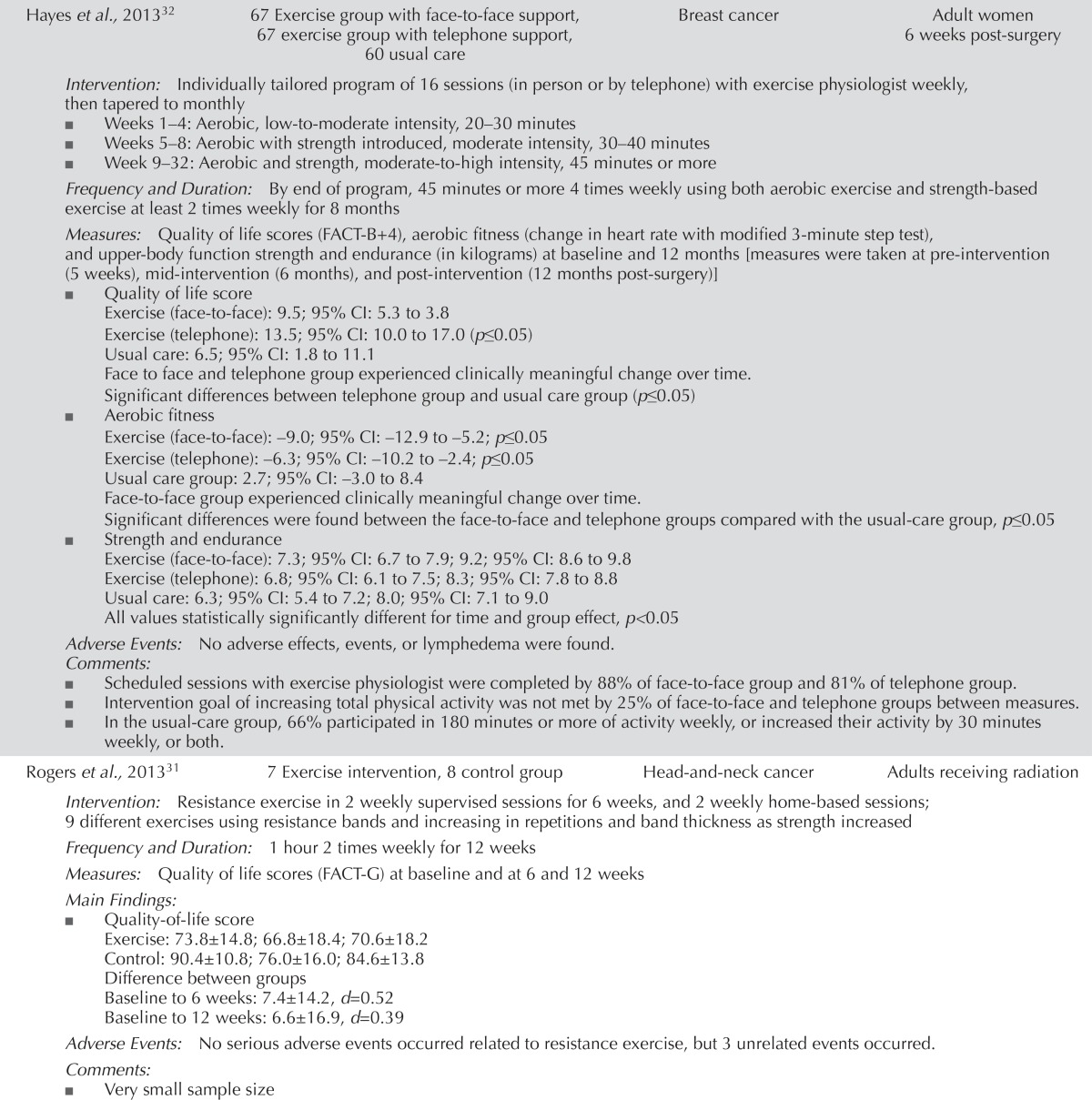

| Hayes et al., 201332 | 67 Exercise group with face-to-face support, 67 exercise group with telephone support, 60 usual care | Breast cancer | Adult women 6 weeks post-surgery |

| Intervention: Individually tailored program of 16 sessions (in person or by telephone) with exercise physiologist weekly, then tapered to monthly | |||

| ■ Weeks 1–4: Aerobic, low-to-moderate intensity, 20–30 minutes | |||

| ■ Weeks 5–8: Aerobic with strength introduced, moderate intensity, 30–40 minutes | |||

| ■ Week 9–32: Aerobic and strength, moderate-to-high intensity, 45 minutes or more | |||

| Frequency and Duration: By end of program, 45 minutes or more 4 times weekly using both aerobic exercise and strength-based exercise at least 2 times weekly for 8 months | |||

| Measures: Quality of life scores (FACT-B+4), aerobic fitness (change in heart rate with modified 3-minute step test), and upper-body function strength and endurance (in kilograms) at baseline and 12 months [measures were taken at pre-intervention (5 weeks), mid-intervention (6 months), and post-intervention (12 months post-surgery)] | |||

| ■ Quality of life score | |||

| Exercise (face-to-face): 9.5; 95% CI: 5.3 to 3.8 | |||

| Exercise (telephone): 13.5; 95% CI: 10.0 to 17.0 (p≤0.05) | |||

| Usual care: 6.5; 95% CI: 1.8 to 11.1 | |||

| Face to face and telephone group experienced clinically meaningful change over time. | |||

| Significant differences between telephone group and usual care group (p≤0.05) | |||

| ■ Aerobic fitness | |||

| Exercise (face-to-face): −9.0; 95% CI: −12.9 to −5.2; p≤0.05 | |||

| Exercise (telephone): −6.3; 95% CI: −10.2 to −2.4; p≤0.05 | |||

| Usual care group: 2.7; 95% CI: −3.0 to 8.4 | |||

| Face-to-face group experienced clinically meaningful change over time. | |||

| Significant differences were found between the face-to-face and telephone groups compared with the usual-care group, p≤0.05 | |||

| ■ Strength and endurance | |||

| Exercise (face-to-face): 7.3; 95% CI: 6.7 to 7.9; 9.2; 95% CI: 8.6 to 9.8 | |||

| Exercise (telephone): 6.8; 95% CI: 6.1 to 7.5; 8.3; 95% CI: 7.8 to 8.8 | |||

| Usual care: 6.3; 95% CI: 5.4 to 7.2; 8.0; 95% CI: 7.1 to 9.0 | |||

| All values statistically significantly different for time and group effect, p<0.05 | |||

| Adverse Events: No adverse effects, events, or lymphedema were found. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Scheduled sessions with exercise physiologist were completed by 88% of face-to-face group and 81% of telephone group. | |||

| ■ Intervention goal of increasing total physical activity was not met by 25% of face-to-face and telephone groups between measures. | |||

| ■ In the usual-care group, 66% participated in 180 minutes or more of activity weekly, or increased their activity by 30 minutes weekly, or both. | |||

| Rogers et al., 201331 | 7 Exercise intervention, 8 control group | Head-and-neck cancer | Adults receiving radiation |

| Intervention: Resistance exercise in 2 weekly supervised sessions for 6 weeks, and 2 weekly home-based sessions; 9 different exercises using resistance bands and increasing in repetitions and band thickness as strength increased | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 1 hour 2 times weekly for 12 weeks | |||

| Measures: Quality of life scores (FACT-G) at baseline and at 6 and 12 weeks | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 73.8±14.8; 66.8±18.4; 70.6±18.2 | |||

| Control: 90.4±10.8; 76.0±16.0; 84.6±13.8 | |||

| Difference between groups | |||

| Baseline to 6 weeks: 7.4±14.2, d=0.52 | |||

| Baseline to 12 weeks: 6.6±16.9, d=0.39 | |||

| Adverse Events: No serious adverse events occurred related to resistance exercise, but 3 unrelated events occurred. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Very small sample size | |||

| Samuel et al., 201330 | 24 Exercise intervention, 24 usual care | Head-and-neck cancer | Adults receiving CTx |

| Intervention: Brisk walking 15–20 minutes at 3–5 rate of perceived exertion, and active weight program for major muscle groups of upper and lower limbs at 3–5/10 rate of perceived exertion; 8–10 repetitions for 2–3 sets | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 5 Times weekly for 6 weeks | |||

| Measures: Quality of life scores (SF-36 mental component summary) and aerobic capacity (6-minute walk distance in metres) | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality of life score | |||

| Exercise: 11.73% increase | |||

| Usual care: 75.21% decrease | |||

| Significant difference between groups, p<0.001 | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity | |||

| Exercise: 42 m increase | |||

| Usual care: 96 m decrease | |||

| Significant difference between groups, p<0.001 | |||

| Adverse Events: None were found. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Adherence not measured. | |||

| Santa Mina et al., 201329 | 32 Aerobic exercise intervention, 34 resistance exercise intervention | Prostate cancer | Adults receiving ADT |

| Intervention: Moderate- to vigorous-intensity home-based sessions, plus 1.5-hour group-based booster sessions every other week (12 sessions) | |||

| ■ Aerobic group: Any modality of aerobic exercise available at 60%–80% maximum heart rate, with progression (focused on walking) | |||

| ■ Resistance training group: 2–3 Sets of 8–12 repetitions at an intensity of 60%–80%, 1 repetition maximum, with resistance bands, exercise mat, and stability ball | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 30–60 minutes, 3–5 days weekly for 6 months | |||

| Measures: Quality of life scores (FACT-P and PORPUS), aerobic capacity (VO2Peak in millilitres per kilogram per minute) and grip strength (in kilograms) at baseline and at 6 months (reported as mean with standard error) | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score (FACT-P) | |||

| Aerobic: 123.9±3.2; 124.2±3.2 | |||

| Resistance: 119.3±3.6; 117.4±4.1 | |||

| Difference between groups: p=0.935 | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score (PORPUS) | |||

| Aerobic: 67.3±2.0; 65.8±2.1 | |||

| Resistance: 62.2±2.0; 62.3±2.2 | |||

| Difference between groups: p=0.625 | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity | |||

| Aerobic: 25.1±1.8; 27.9±2.0 | |||

| Resistance: 28.4±1.6; 30.5±1.6 | |||

| Difference between groups: p=0.565 | |||

| ■ Grip strength | |||

| Aerobic: 63.9±2.6; 64.5±2.7 | |||

| Resistance: 69.6±2.0; 68.9±2.3 | |||

| Difference between group: p=0.865 | |||

| Adverse Events: There were no serious adverse events related to exercise interventions beyond the expected muscle soreness associated with novel exercise. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Aerobic group attended 16.4% of booster sessions; 27 participants did not attend any such session. | |||

| Resistance group attended 5.5% of sessions; 22 did not attend any. | |||

| ■ Log books not completed effectively. | |||

| ■ No control group | |||

| ■ Small sample size | |||

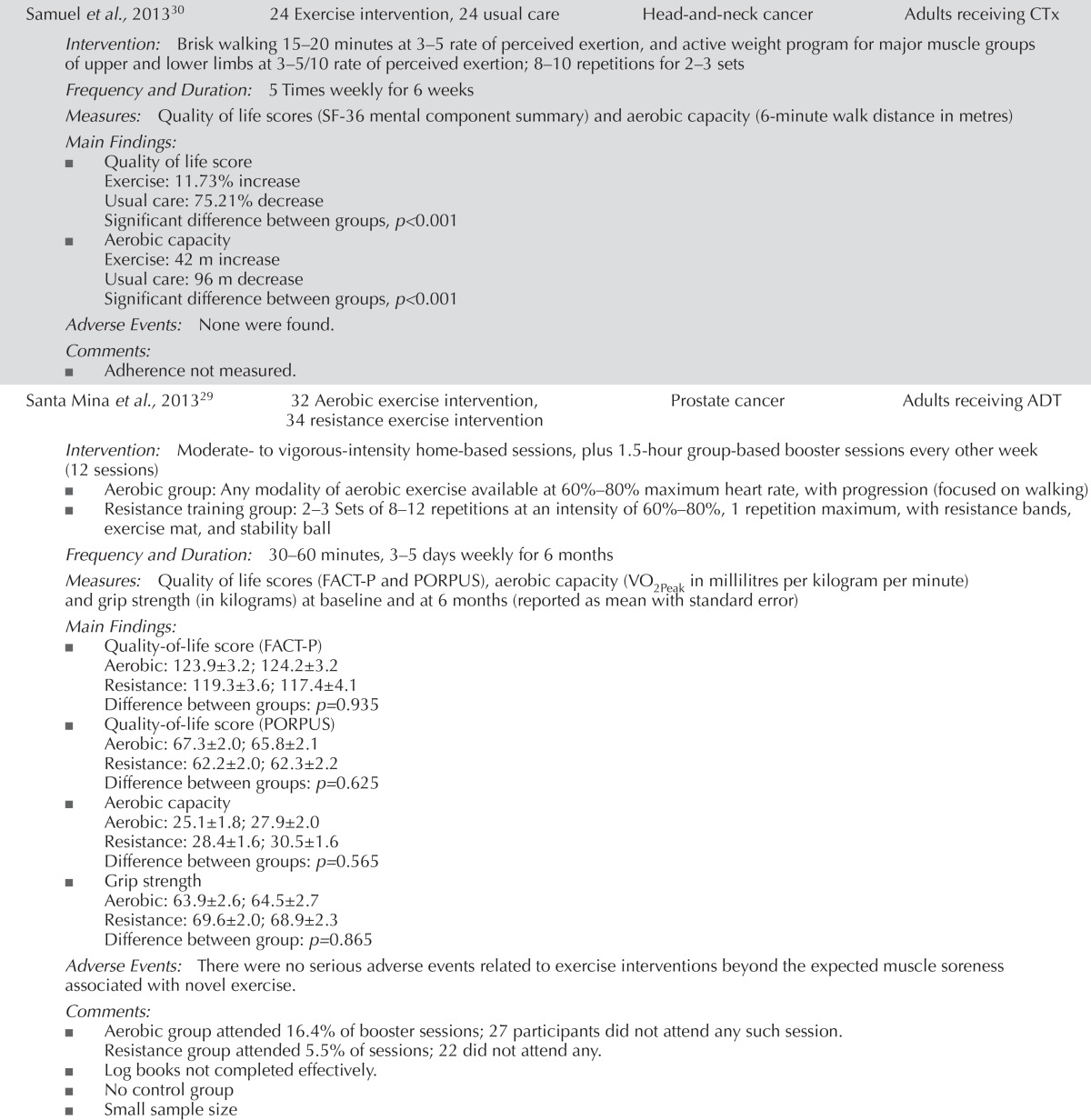

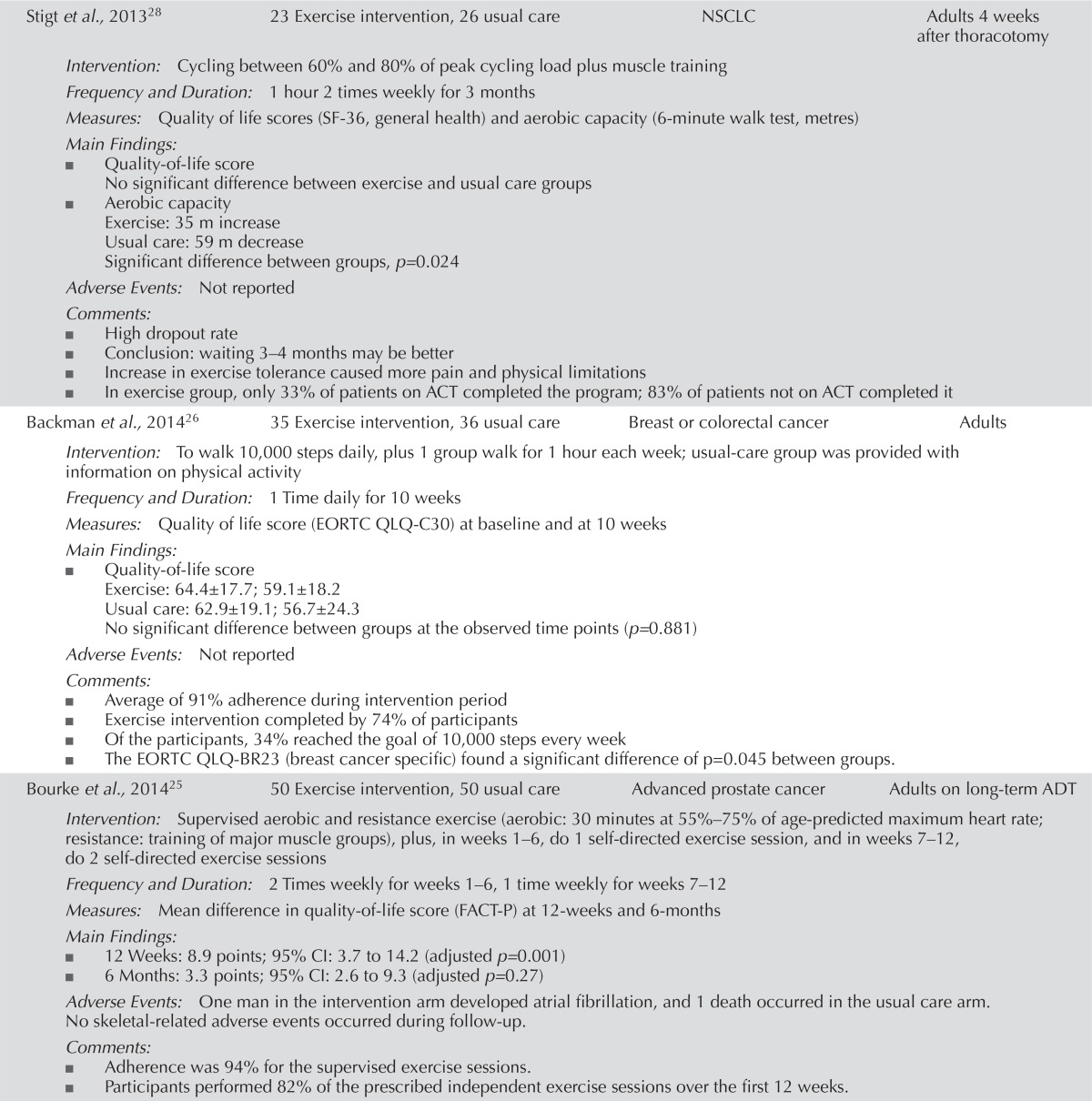

| Stigt et al., 201328 | 23 Exercise intervention, 26 usual care | NSCLC | Adults 4 weeks after thoracotomy |

| Intervention: Cycling between 60% and 80% of peak cycling load plus muscle training | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 1 hour 2 times weekly for 3 months | |||

| Measures: Quality of life scores (SF-36, general health) and aerobic capacity (6-minute walk test, metres) | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| No significant difference between exercise and usual care groups | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity | |||

| Exercise: 35 m increase | |||

| Usual care: 59 m decrease | |||

| Significant difference between groups, p=0.024 | |||

| Adverse Events: Not reported | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ High dropout rate | |||

| ■ Conclusion: waiting 3–4 months may be better | |||

| ■ Increase in exercise tolerance caused more pain and physical limitations | |||

| ■ In exercise group, only 33% of patients on ACT completed the program; 83% of patients not on ACT completed it | |||

| Backman et al., 201426 | 35 Exercise intervention, 36 usual care | Breast or colorectal cancer | Adults |

| Intervention: To walk 10,000 steps daily, plus 1 group walk for 1 hour each week; usual-care group was provided with information on physical activity | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 1 Time daily for 10 weeks | |||

| Measures: Quality of life score (EORTC QLQ-C30) at baseline and at 10 weeks | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 64.4±17.7; 59.1±18.2 | |||

| Usual care: 62.9±19.1; 56.7±24.3 | |||

| No significant difference between groups at the observed time points (p=0.881) | |||

| Adverse Events: Not reported | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Average of 91% adherence during intervention period | |||

| ■ Exercise intervention completed by 74% of participants | |||

| ■ Of the participants, 34% reached the goal of 10,000 steps every week | |||

| ■ The EORTC QLQ-BR23 (breast cancer specific) found a significant difference of p=0.045 between groups. | |||

| Bourke et al., 201425 | 50 Exercise intervention, 50 usual care | Advanced prostate cancer | Adults on long-term ADT |

| Intervention: Supervised aerobic and resistance exercise (aerobic: 30 minutes at 55%–75% of age-predicted maximum heart rate; resistance: training of major muscle groups), plus, in weeks 1–6, do 1 self-directed exercise session, and in weeks 7–12, do 2 self-directed exercise sessions | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 2 Times weekly for weeks 1–6, 1 time weekly for weeks 7–12 | |||

| Measures: Mean difference in quality-of-life score (FACT-P) at 12-weeks and 6-months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ 12 Weeks: 8.9 points; 95% CI: 3.7 to 14.2 (adjusted p=0.001) | |||

| ■ 6 Months: 3.3 points; 95% CI: 2.6 to 9.3 (adjusted p=0.27) | |||

| Adverse Events: One man in the intervention arm developed atrial fibrillation, and 1 death occurred in the usual care arm. | |||

| No skeletal-related adverse events occurred during follow-up. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Adherence was 94% for the supervised exercise sessions. | |||

| ■ Participants performed 82% of the prescribed independent exercise sessions over the first 12 weeks. | |||

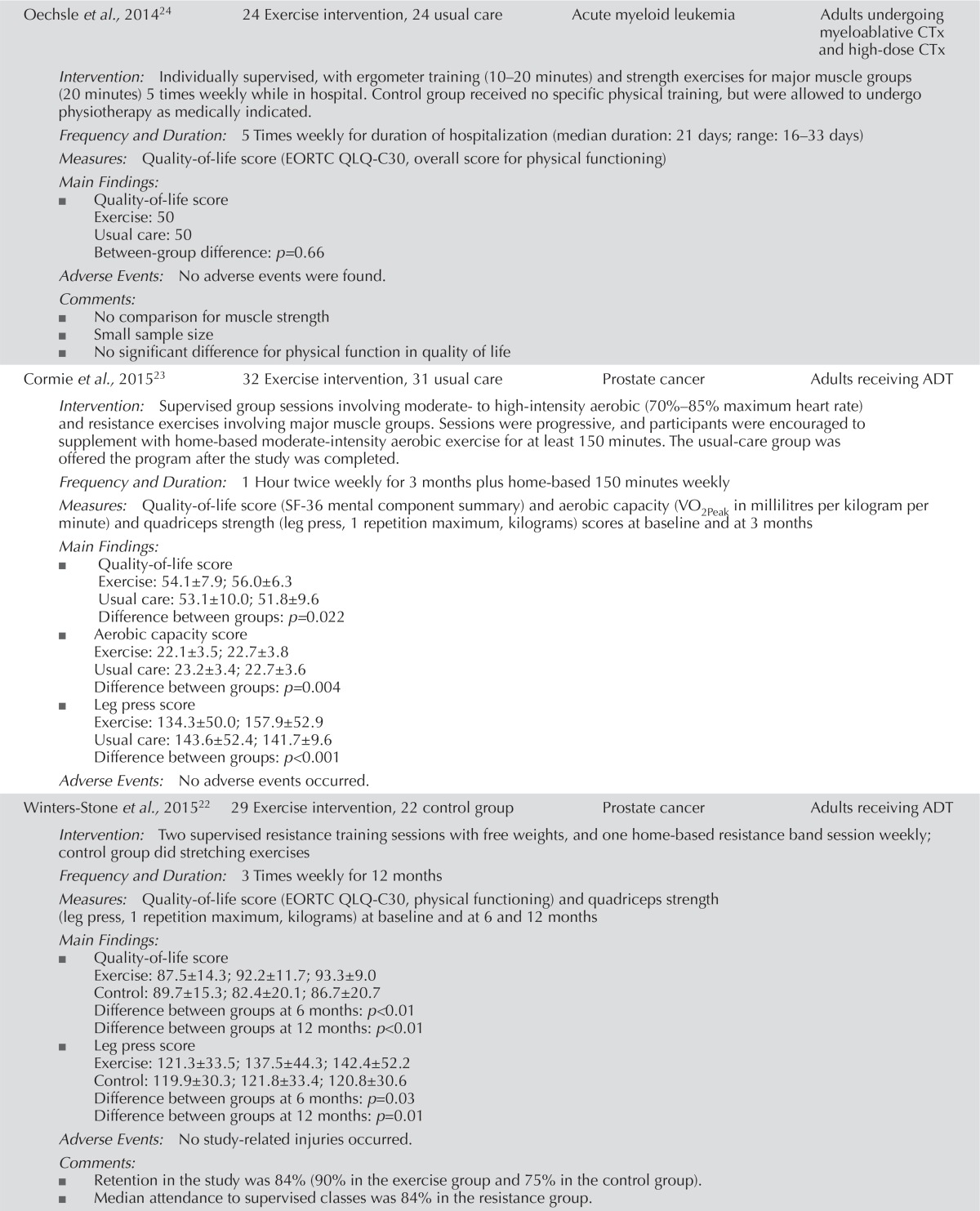

| Oechsle et al., 201424 | 24 Exercise intervention, 24 usual care | Acute myeloid leukemia | Adults undergoing myeloablative CTx and high-dose CTx |

| Intervention: Individually supervised, with ergometer training (10–20 minutes) and strength exercises for major muscle groups (20 minutes) 5 times weekly while in hospital. Control group received no specific physical training, but were allowed to undergo physiotherapy as medically indicated. | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 5 Times weekly for duration of hospitalization (median duration: 21 days; range: 16–33 days) | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life score (EORTC QLQ-C30, overall score for physical functioning) | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 50 | |||

| Usual care: 50 | |||

| Between-group difference: p=0.66 | |||

| Adverse Events: No adverse events were found. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ No comparison for muscle strength | |||

| ■ Small sample size | |||

| ■ No significant difference for physical function in quality of life | |||

| Cormie et al., 201523 | 32 Exercise intervention, 31 usual care | Prostate cancer | Adults receiving ADT |

| Intervention: Supervised group sessions involving moderate- to high-intensity aerobic (70%–85% maximum heart rate) and resistance exercises involving major muscle groups. Sessions were progressive, and participants were encouraged to supplement with home-based moderate-intensity aerobic exercise for at least 150 minutes. The usual-care group was offered the program after the study was completed. | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 1 Hour twice weekly for 3 months plus home-based 150 minutes weekly | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life score (SF-36 mental component summary) and aerobic capacity (VO2Peak in millilitres per kilogram per minute) and quadriceps strength (leg press, 1 repetition maximum, kilograms) scores at baseline and at 3 months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 54.1±7.9; 56.0±6.3 | |||

| Usual care: 53.1±10.0; 51.8±9.6 | |||

| Difference between groups: p=0.022 | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity score | |||

| Exercise: 22.1±3.5; 22.7±3.8 | |||

| Usual care: 23.2±3.4; 22.7±3.6 | |||

| Difference between groups: p=0.004 | |||

| ■ Leg press score | |||

| Exercise: 134.3±50.0; 157.9±52.9 | |||

| Usual care: 143.6±52.4; 141.7±9.6 | |||

| Difference between groups: p<0.001 | |||

| Adverse Events: No adverse events occurred. | |||

| Winters-Stone et al., 201522 | 29 Exercise intervention, 22 control group | Prostate cancer | Adults receiving ADT |

| Intervention: Two supervised resistance training sessions with free weights, and one home-based resistance band session weekly; control group did stretching exercises | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 3 Times weekly for 12 months | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life score (EORTC QLQ-C30, physical functioning) and quadriceps strength (leg press, 1 repetition maximum, kilograms) at baseline and at 6 and 12 months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 87.5±14.3; 92.2±11.7; 93.3±9.0 | |||

| Control: 89.7±15.3; 82.4±20.1; 86.7±20.7 | |||

| Difference between groups at 6 months: p<0.01 | |||

| Difference between groups at 12 months: p<0.01 | |||

| ■ Leg press score | |||

| Exercise: 121.3±33.5; 137.5±44.3; 142.4±52.2 | |||

| Control: 119.9±30.3; 121.8±33.4; 120.8±30.6 | |||

| Difference between groups at 6 months: p=0.03 | |||

| Difference between groups at 12 months: p=0.01 | |||

| Adverse Events: No study-related injuries occurred. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Retention in the study was 84% (90% in the exercise group and 75% in the control group). | |||

| ■ Median attendance to supervised classes was 84% in the resistance group. | |||

| Post treatment | |||

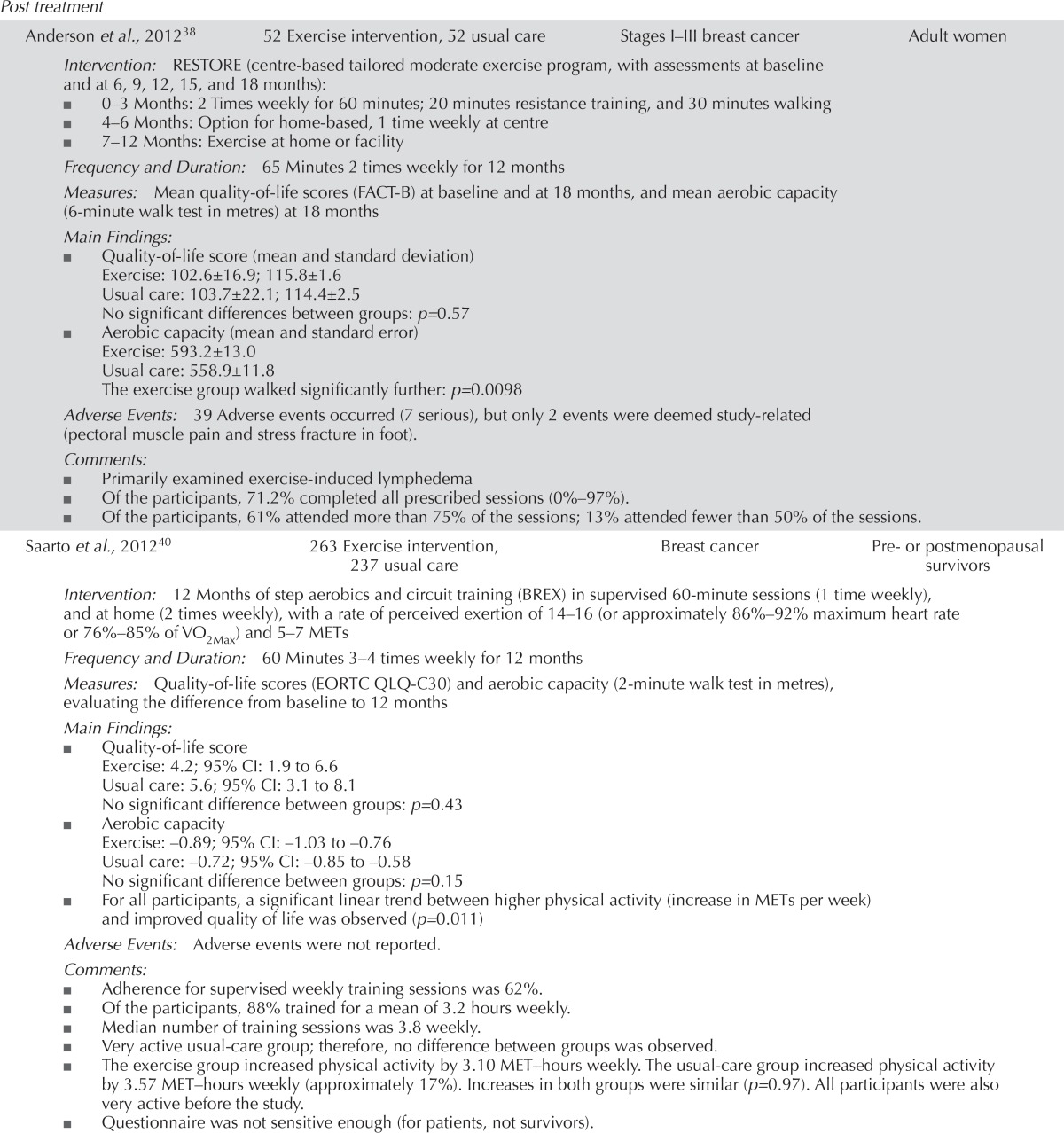

| Anderson et al., 201238 | 52 Exercise intervention, 52 usual care | Stages I–III breast cancer | Adult women |

| Intervention: RESTORE (centre-based tailored moderate exercise program, with assessments at baseline and at 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months): | |||

| ■ 0–3 Months: 2 Times weekly for 60 minutes; 20 minutes resistance training, and 30 minutes walking | |||

| ■ 4–6 Months: Option for home-based, 1 time weekly at centre | |||

| ■ 7–12 Months: Exercise at home or facility | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 65 Minutes 2 times weekly for 12 months | |||

| Measures: Mean quality-of-life scores (FACT-B) at baseline and at 18 months, and mean aerobic capacity (6-minute walk test in metres) at 18 months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score (mean and standard deviation) | |||

| Exercise: 102.6±16.9; 115.8±1.6 | |||

| Usual care: 103.7±22.1; 114.4±2.5 | |||

| No significant differences between groups: p=0.57 | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity (mean and standard error) | |||

| Exercise: 593.2±13.0 | |||

| Usual care: 558.9±11.8 | |||

| The exercise group walked significantly further: p=0.0098 | |||

| Adverse Events: 39 Adverse events occurred (7 serious), but only 2 events were deemed study-related (pectoral muscle pain and stress fracture in foot). | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Primarily examined exercise-induced lymphedema | |||

| ■ Of the participants, 71.2% completed all prescribed sessions (0%–97%). | |||

| ■ Of the participants, 61% attended more than 75% of the sessions; 13% attended fewer than 50% of the sessions. | |||

| Saarto et al., 201240 | 263 Exercise intervention, 237 usual care | Breast cancer | Pre- or postmenopausal survivors |

| Intervention: 12 Months of step aerobics and circuit training (BREX) in supervised 60-minute sessions (1 time weekly), and at home (2 times weekly), with a rate of perceived exertion of 14–16 (or approximately 86%–92% maximum heart rate or 76%–85% of VO2Max) and 5–7 METs | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 60 Minutes 3–4 times weekly for 12 months | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (EORTC QLQ-C30) and aerobic capacity (2-minute walk test in metres), evaluating the difference from baseline to 12 months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 4.2; 95% CI: 1.9 to 6.6 | |||

| Usual care: 5.6; 95% CI: 3.1 to 8.1 | |||

| No significant difference between groups: p=0.43 | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity | |||

| Exercise: −0.89; 95% CI: −1.03 to −0.76 | |||

| Usual care: −0.72; 95% CI: −0.85 to −0.58 | |||

| No significant difference between groups: p=0.15 | |||

| ■ For all participants, a significant linear trend between higher physical activity (increase in METs per week) and improved quality of life was observed (p=0.011) | |||

| Adverse Events: Adverse events were not reported. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Adherence for supervised weekly training sessions was 62%. | |||

| ■ Of the participants, 88% trained for a mean of 3.2 hours weekly. | |||

| ■ Median number of training sessions was 3.8 weekly. | |||

| ■ Very active usual-care group; therefore, no difference between groups was observed. | |||

| ■ The exercise group increased physical activity by 3.10 MET–hours weekly. The usual-care group increased physical activity by 3.57 MET–hours weekly (approximately 17%). Increases in both groups were similar (p=0.97). All participants were also very active before the study. | |||

| ■ Questionnaire was not sensitive enough (for patients, not survivors). | |||

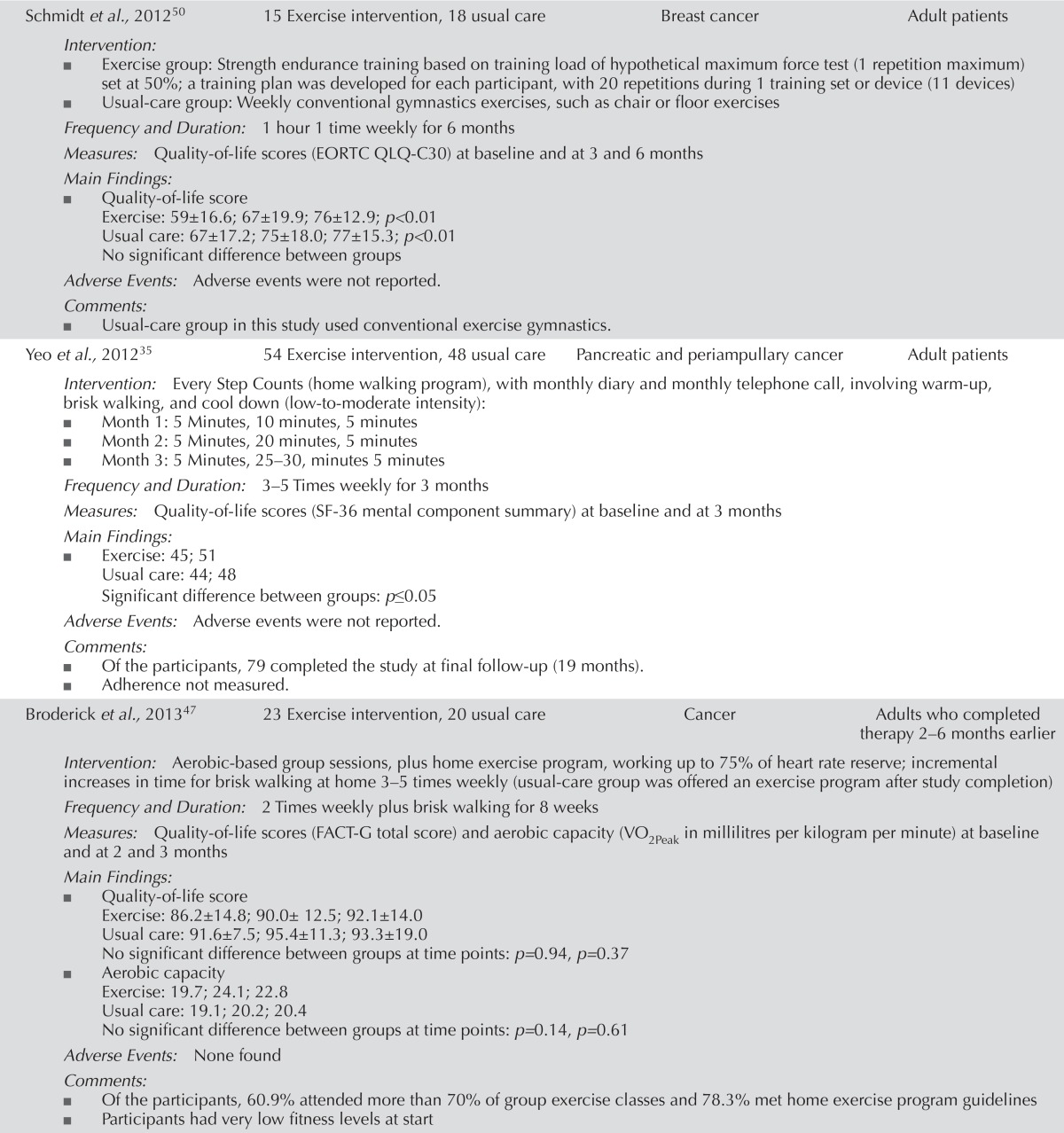

| Schmidt et al., 201250 | 15 Exercise intervention, 18 usual care | Breast cancer | Adult patients |

| Intervention: | |||

| ■ Exercise group: Strength endurance training based on training load of hypothetical maximum force test (1 repetition maximum) set at 50%; a training plan was developed for each participant, with 20 repetitions during 1 training set or device (11 devices) | |||

| ■ Usual-care group: Weekly conventional gymnastics exercises, such as chair or floor exercises | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 1 hour 1 time weekly for 6 months | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (EORTC QLQ-C30) at baseline and at 3 and 6 months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 59±16.6; 67±19.9; 76±12.9; p<0.01 | |||

| Usual care: 67±17.2; 75±18.0; 77±15.3; p<0.01 | |||

| No significant difference between groups | |||

| Adverse Events: Adverse events were not reported. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Usual-care group in this study used conventional exercise gymnastics. | |||

| Yeo et al., 201235 | 54 Exercise intervention, 48 usual care | Pancreatic and periampullary cancer | Adult patients |

| Intervention: Every Step Counts (home walking program), with monthly diary and monthly telephone call, involving warm-up, brisk walking, and cool down (low-to-moderate intensity): | |||

| ■ Month 1: 5 Minutes, 10 minutes, 5 minutes | |||

| ■ Month 2: 5 Minutes, 20 minutes, 5 minutes | |||

| ■ Month 3: 5 Minutes, 25–30, minutes 5 minutes | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 3–5 Times weekly for 3 months | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (SF-36 mental component summary) at baseline and at 3 months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Exercise: 45; 51 | |||

| Usual care: 44; 48 | |||

| Significant difference between groups: p≤0.05 | |||

| Adverse Events: Adverse events were not reported. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Of the participants, 79 completed the study at final follow-up (19 months). | |||

| ■ Adherence not measured. | |||

| Broderick et al., 201347 | 23 Exercise intervention, 20 usual care | Cancer | Adults who completed therapy 2–6 months earlier |

| Intervention: Aerobic-based group sessions, plus home exercise program, working up to 75% of heart rate reserve; incremental increases in time for brisk walking at home 3–5 times weekly (usual-care group was offered an exercise program after study completion) | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 2 Times weekly plus brisk walking for 8 weeks | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (FACT-G total score) and aerobic capacity (VO2Peak in millilitres per kilogram per minute) at baseline and at 2 and 3 months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 86.2±14.8; 90.0± 12.5; 92.1±14.0 | |||

| Usual care: 91.6±7.5; 95.4±11.3; 93.3±19.0 | |||

| No significant difference between groups at time points: p=0.94, p=0.37 | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity | |||

| Exercise: 19.7; 24.1; 22.8 | |||

| Usual care: 19.1; 20.2; 20.4 | |||

| No significant difference between groups at time points: p=0.14, p=0.61 | |||

| Adverse Events: None found | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Of the participants, 60.9% attended more than 70% of group exercise classes and 78.3% met home exercise program guidelines | |||

| ■ Participants had very low fitness levels at start | |||

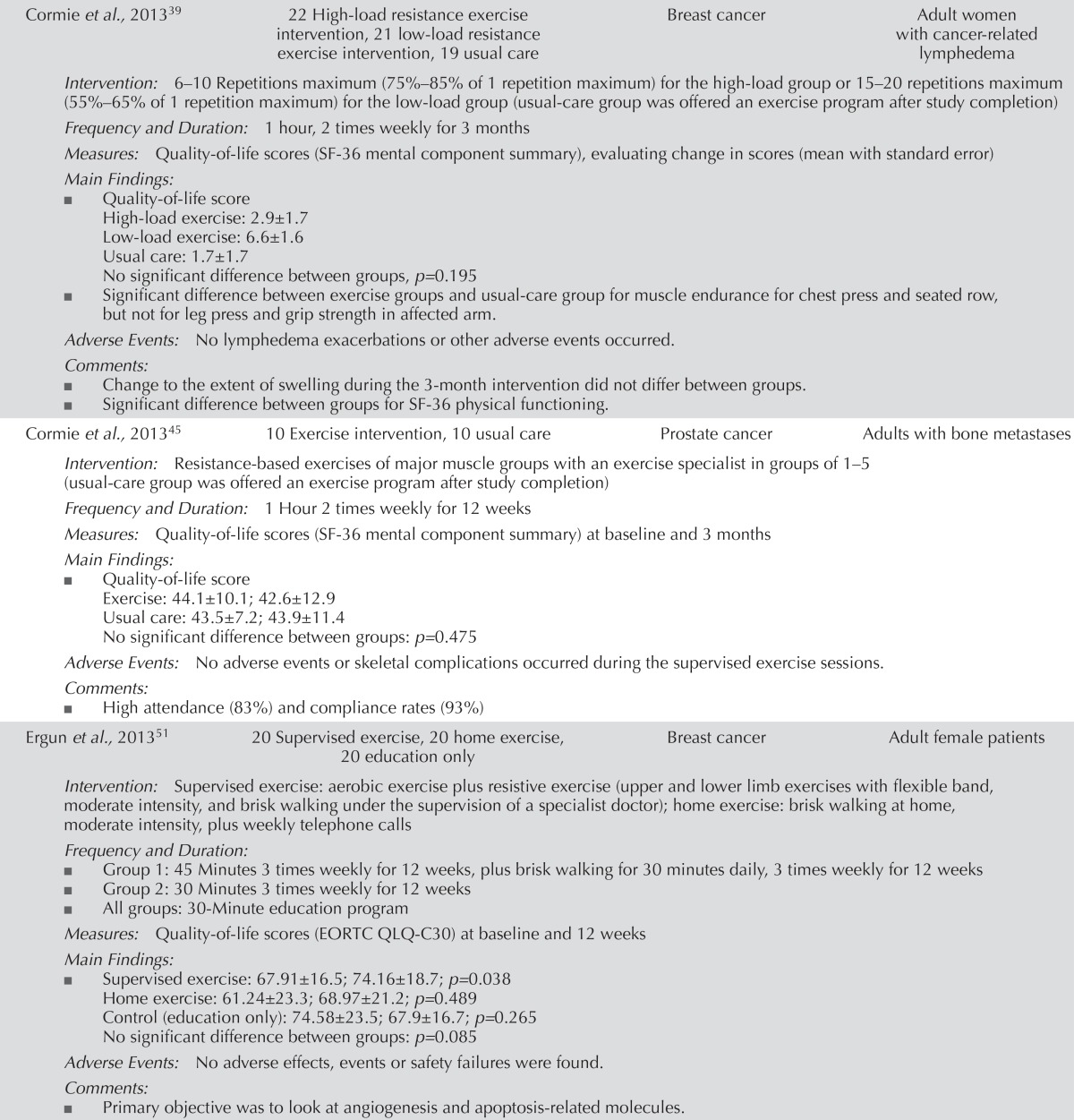

| Cormie et al., 201339 | 22 High-load resistance exercise intervention, 21 low-load resistance exercise intervention, 19 usual care | Breast cancer | Adult women with cancer-related lymphedema |

| Intervention: 6–10 Repetitions maximum (75%–85% of 1 repetition maximum) for the high-load group or 15–20 repetitions maximum (55%–65% of 1 repetition maximum) for the low-load group (usual-care group was offered an exercise program after study completion) | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 1 hour, 2 times weekly for 3 months | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (SF-36 mental component summary), evaluating change in scores (mean with standard error) | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| High-load exercise: 2.9±1.7 | |||

| Low-load exercise: 6.6±1.6 | |||

| Usual care: 1.7±1.7 | |||

| No significant difference between groups, p=0.195 | |||

| ■ Significant difference between exercise groups and usual-care group for muscle endurance for chest press and seated row, but not for leg press and grip strength in affected arm. | |||

| Adverse Events: No lymphedema exacerbations or other adverse events occurred. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Change to the extent of swelling during the 3-month intervention did not differ between groups. | |||

| ■ Significant difference between groups for SF-36 physical functioning. | |||

| Cormie et al., 201345 | 10 Exercise intervention, 10 usual care | Prostate cancer | Adults with bone metastases |

| Intervention: Resistance-based exercises of major muscle groups with an exercise specialist in groups of 1–5 (usual-care group was offered an exercise program after study completion) | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 1 Hour 2 times weekly for 12 weeks | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (SF-36 mental component summary) at baseline and 3 months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 44.1±10.1; 42.6±12.9 | |||

| Usual care: 43.5±7.2; 43.9±11.4 | |||

| No significant difference between groups: p=0.475 | |||

| Adverse Events: No adverse events or skeletal complications occurred during the supervised exercise sessions. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ High attendance (83%) and compliance rates (93%) | |||

| Ergun et al., 201351 | 20 Supervised exercise, 20 home exercise, 20 education only | Breast cancer | Adult female patients |

| Intervention: Supervised exercise: aerobic exercise plus resistive exercise (upper and lower limb exercises with flexible band, moderate intensity, and brisk walking under the supervision of a specialist doctor); home exercise: brisk walking at home, moderate intensity, plus weekly telephone calls | |||

| Frequency and Duration: | |||

| ■ Group 1: 45 Minutes 3 times weekly for 12 weeks, plus brisk walking for 30 minutes daily, 3 times weekly for 12 weeks | |||

| ■ Group 2: 30 Minutes 3 times weekly for 12 weeks | |||

| ■ All groups: 30-Minute education program | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (EORTC QLQ-C30) at baseline and 12 weeks | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Supervised exercise: 67.91±16.5; 74.16±18.7; p=0.038 | |||

| Home exercise: 61.24±23.3; 68.97±21.2; p=0.489 | |||

| Control (education only): 74.58±23.5; 67.9±16.7; p=0.265 | |||

| No significant difference between groups: p=0.085 | |||

| Adverse Events: No adverse effects, events or safety failures were found. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Primary objective was to look at angiogenesis and apoptosis-related molecules. | |||

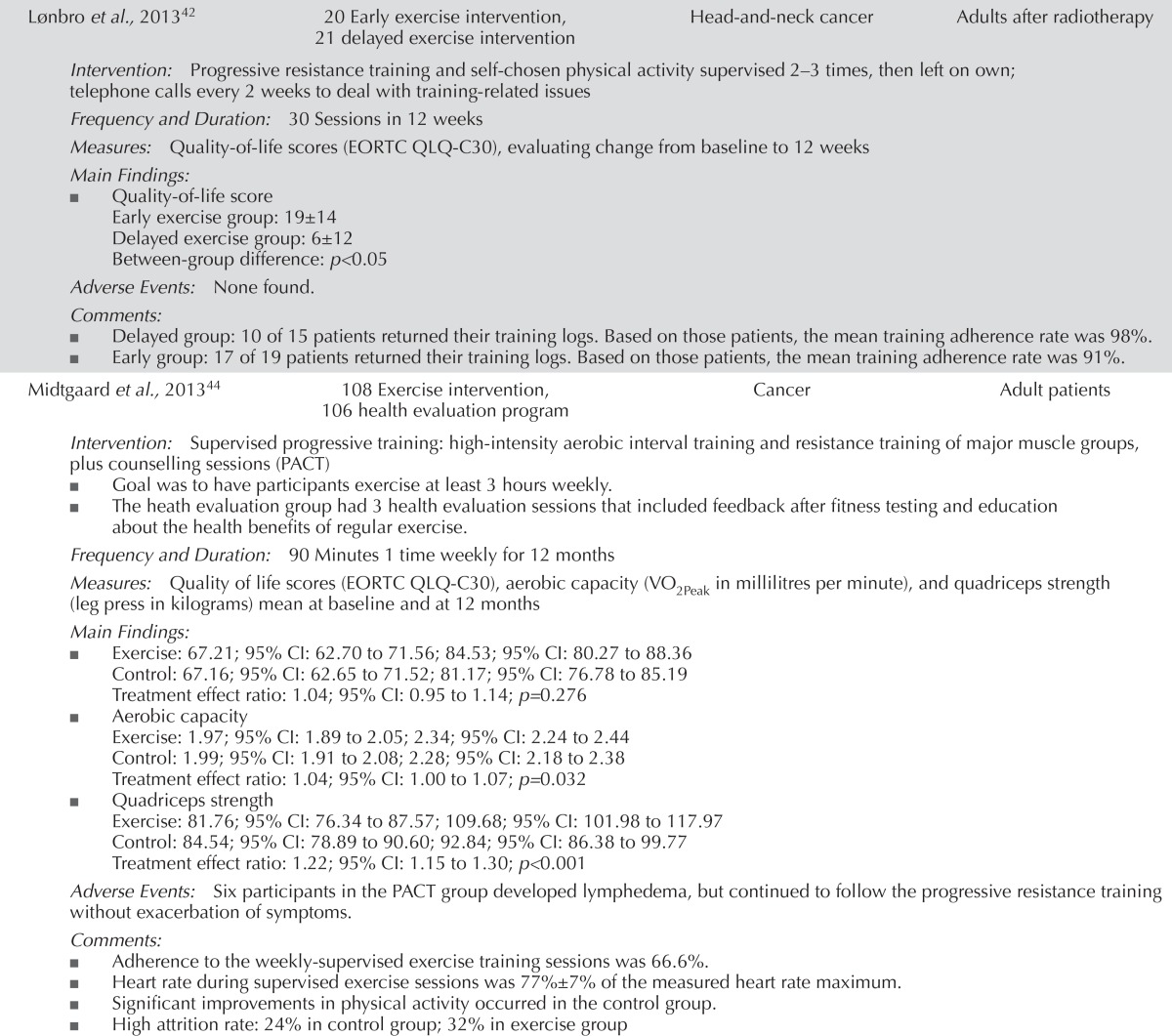

| Lønbro et al., 201342 | 20 Early exercise intervention, 21 delayed exercise intervention | Head-and-neck cancer | Adults after radiotherapy |

| Intervention: Progressive resistance training and self-chosen physical activity supervised 2–3 times, then left on own; telephone calls every 2 weeks to deal with training-related issues | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 30 Sessions in 12 weeks | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (EORTC QLQ-C30), evaluating change from baseline to 12 weeks | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Early exercise group: 19±14 | |||

| Delayed exercise group: 6±12 | |||

| Between-group difference: p<0.05 | |||

| Adverse Events: None found. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Delayed group: 10 of 15 patients returned their training logs. Based on those patients, the mean training adherence rate was 98%. | |||

| ■ Early group: 17 of 19 patients returned their training logs. Based on those patients, the mean training adherence rate was 91%. | |||

| Midtgaard et al., 201344 | 108 Exercise intervention, 106 health evaluation program | Cancer | Adult patients |

| Intervention: Supervised progressive training: high-intensity aerobic interval training and resistance training of major muscle groups, plus counselling sessions (PACT) | |||

| ■ Goal was to have participants exercise at least 3 hours weekly. | |||

| ■ The heath evaluation group had 3 health evaluation sessions that included feedback after fitness testing and education about the health benefits of regular exercise. | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 90 Minutes 1 time weekly for 12 months | |||

| Measures: Quality of life scores (EORTC QLQ-C30), aerobic capacity (VO2Peak in millilitres per minute), and quadriceps strength (leg press in kilograms) mean at baseline and at 12 months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Exercise: 67.21; 95% CI: 62.70 to 71.56; 84.53; 95% CI: 80.27 to 88.36 | |||

| Control: 67.16; 95% CI: 62.65 to 71.52; 81.17; 95% CI: 76.78 to 85.19 | |||

| Treatment effect ratio: 1.04; 95% CI: 0.95 to 1.14; p=0.276 | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity | |||

| Exercise: 1.97; 95% CI: 1.89 to 2.05; 2.34; 95% CI: 2.24 to 2.44 | |||

| Control: 1.99; 95% CI: 1.91 to 2.08; 2.28; 95% CI: 2.18 to 2.38 | |||

| Treatment effect ratio: 1.04; 95% CI: 1.00 to 1.07; p=0.032 | |||

| ■ Quadriceps strength | |||

| Exercise: 81.76; 95% CI: 76.34 to 87.57; 109.68; 95% CI: 101.98 to 117.97 | |||

| Control: 84.54; 95% CI: 78.89 to 90.60; 92.84; 95% CI: 86.38 to 99.77 | |||

| Treatment effect ratio: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.15 to 1.30; p<0.001 | |||

| Adverse Events: Six participants in the PACT group developed lymphedema, but continued to follow the progressive resistance training without exacerbation of symptoms. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Adherence to the weekly-supervised exercise training sessions was 66.6%. | |||

| ■ Heart rate during supervised exercise sessions was 77%±7% of the measured heart rate maximum. | |||

| ■ Significant improvements in physical activity occurred in the control group. | |||

| ■ High attrition rate: 24% in control group; 32% in exercise group | |||

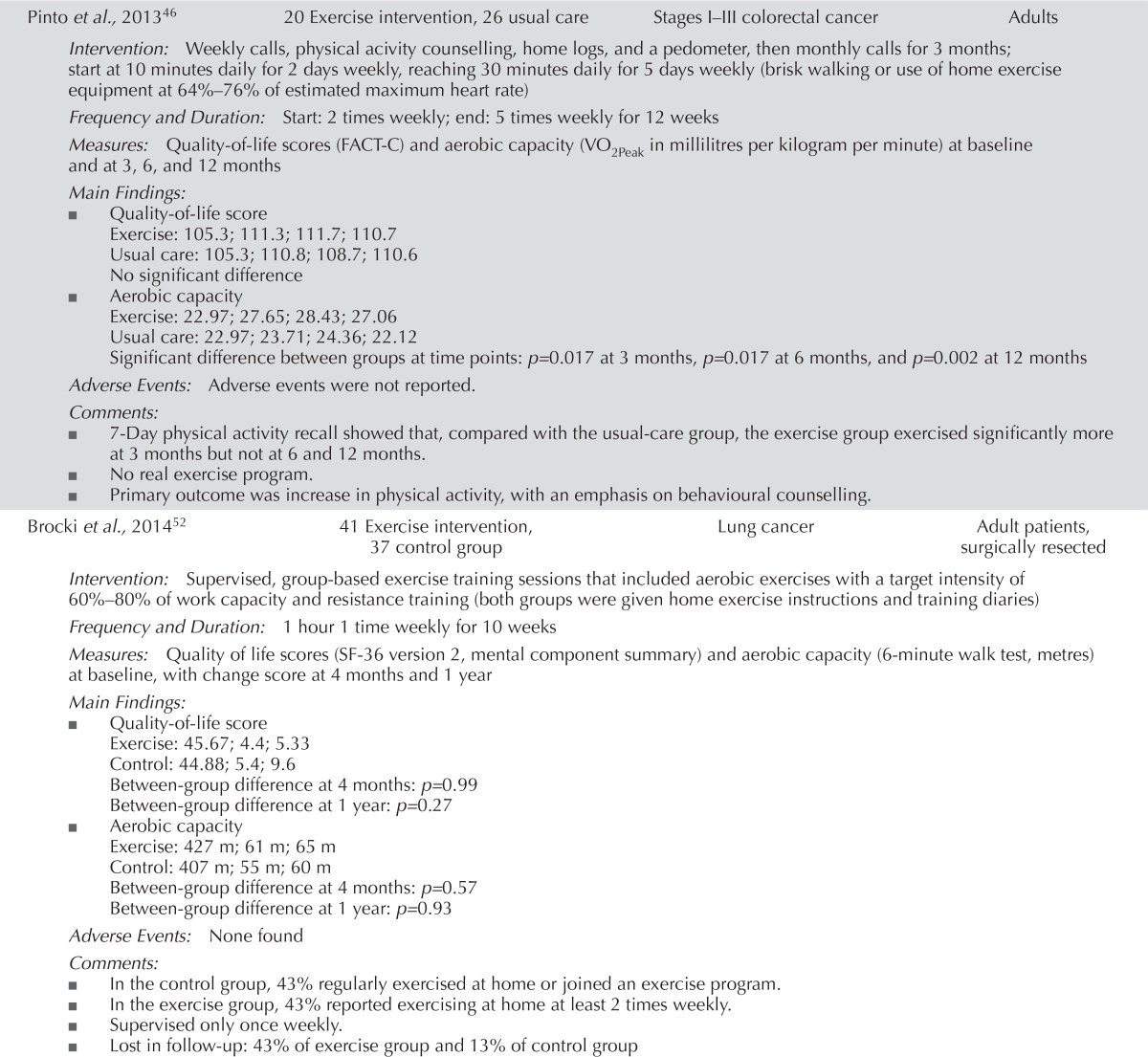

| Pinto et al., 201346 | 20 Exercise intervention, 26 usual care | Stages I–III colorectal cancer | Adults |

| Intervention: Weekly calls, physical acivity counselling, home logs, and a pedometer, then monthly calls for 3 months; start at 10 minutes daily for 2 days weekly, reaching 30 minutes daily for 5 days weekly (brisk walking or use of home exercise equipment at 64%–76% of estimated maximum heart rate) | |||

| Frequency and Duration: Start: 2 times weekly; end: 5 times weekly for 12 weeks | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (FACT-C) and aerobic capacity (VO2Peak in millilitres per kilogram per minute) at baseline and at 3, 6, and 12 months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 105.3; 111.3; 111.7; 110.7 | |||

| Usual care: 105.3; 110.8; 108.7; 110.6 | |||

| No significant difference | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity | |||

| Exercise: 22.97; 27.65; 28.43; 27.06 | |||

| Usual care: 22.97; 23.71; 24.36; 22.12 | |||

| Significant difference between groups at time points: p=0.017 at 3 months, p= 0.017 at 6 months, and p=0.002 at 12 months | |||

| Adverse Events: Adverse events were not reported. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ 7-Day physical activity recall showed that, compared with the usual-care group, the exercise group exercised significantly more at 3 months but not at 6 and 12 months. | |||

| ■ No real exercise program. | |||

| ■ Primary outcome was increase in physical activity, with an emphasis on behavioural counselling. | |||

| Brocki et al., 201452 | 41 Exercise intervention, 37 control group | Lung cancer | Adult patients, surgically resected |

| Intervention: Supervised, group-based exercise training sessions that included aerobic exercises with a target intensity of 60%–80% of work capacity and resistance training (both groups were given home exercise instructions and training diaries) | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 1 hour 1 time weekly for 10 weeks | |||

| Measures: Quality of life scores (SF-36 version 2, mental component summary) and aerobic capacity (6-minute walk test, metres) at baseline, with change score at 4 months and 1 year | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 45.67; 4.4; 5.33 | |||

| Control: 44.88; 5.4; 9.6 | |||

| Between-group difference at 4 months: p=0.99 | |||

| Between-group difference at 1 year: p=0.27 | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity | |||

| Exercise: 427 m; 61 m; 65 m | |||

| Control: 407 m; 55 m; 60 m | |||

| Between-group difference at 4 months: p=0.57 | |||

| Between-group difference at 1 year: p=0.93 | |||

| Adverse Events: None found | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ In the control group, 43% regularly exercised at home or joined an exercise program. | |||

| ■ In the exercise group, 43% reported exercising at home at least 2 times weekly. | |||

| ■ Supervised only once weekly. | |||

| ■ Lost in follow-up: 43% of exercise group and 13% of control group | |||

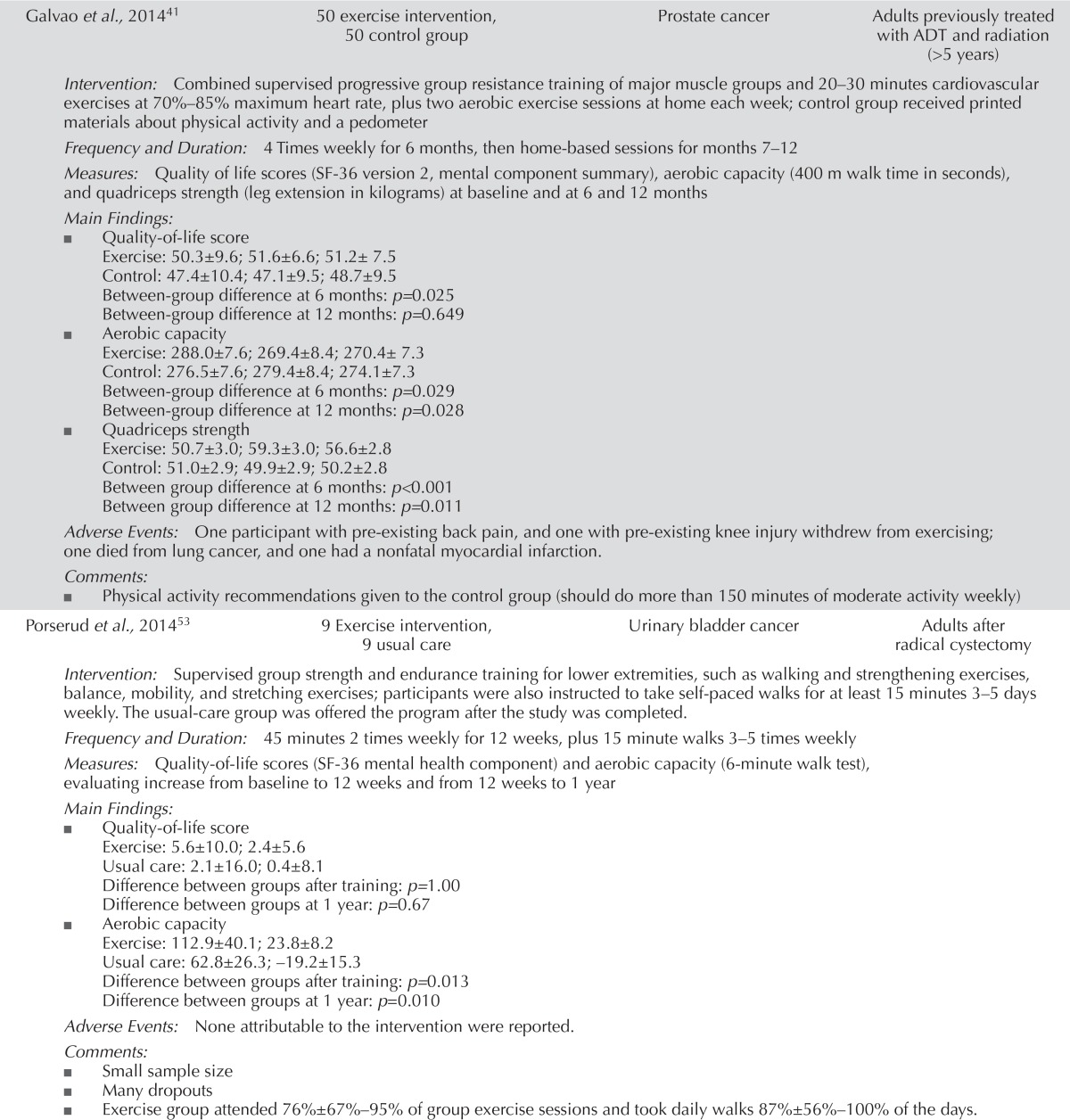

| Galvao et al., 201441 | 50 exercise intervention, 50 control group | Prostate cancer | Adults previously treated with ADT and radiation (>5 years) |

| Intervention: Combined supervised progressive group resistance training of major muscle groups and 20–30 minutes cardiovascular exercises at 70%–85% maximum heart rate, plus two aerobic exercise sessions at home each week; control group received printed materials about physical activity and a pedometer | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 4 Times weekly for 6 months, then home-based sessions for months 7–12 | |||

| Measures: Quality of life scores (SF-36 version 2, mental component summary), aerobic capacity (400 m walk time in seconds), and quadriceps strength (leg extension in kilograms) at baseline and at 6 and 12 months | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 50.3±9.6; 51.6±6.6; 51.2± 7.5 | |||

| Control: 47.4±10.4; 47.1±9.5; 48.7±9.5 | |||

| Between-group difference at 6 months: p=0.025 | |||

| Between-group difference at 12 months: p=0.649 | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity | |||

| Exercise: 288.0±7.6; 269.4±8.4; 270.4± 7.3 | |||

| Control: 276.5±7.6; 279.4±8.4; 274.1±7.3 | |||

| Between-group difference at 6 months: p=0.029 | |||

| Between-group difference at 12 months: p=0.028 | |||

| ■ Quadriceps strength | |||

| Exercise: 50.7±3.0; 59.3±3.0; 56.6±2.8 | |||

| Control: 51.0±2.9; 49.9±2.9; 50.2±2.8 | |||

| Between group difference at 6 months: p<0.001 | |||

| Between group difference at 12 months: p=0.011 | |||

| Adverse Events: One participant with pre-existing back pain, and one with pre-existing knee injury withdrew from exercising; one died from lung cancer, and one had a nonfatal myocardial infarction. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Physical activity recommendations given to the control group (should do more than 150 minutes of moderate activity weekly) | |||

| Porserud et al., 201453 | 9 Exercise intervention, 9 usual care | Urinary bladder cancer | Adults after radical cystectomy |

| Intervention: Supervised group strength and endurance training for lower extremities, such as walking and strengthening exercises, balance, mobility, and stretching exercises; participants were also instructed to take self-paced walks for at least 15 minutes 3–5 days weekly. The usual-care group was offered the program after the study was completed. | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 45 minutes 2 times weekly for 12 weeks, plus 15 minute walks 3–5 times weekly | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (SF-36 mental health component) and aerobic capacity (6-minute walk test), evaluating increase from baseline to 12 weeks and from 12 weeks to 1 year | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 5.6±10.0; 2.4±5.6 | |||

| Usual care: 2.1±16.0; 0.4±8.1 | |||

| Difference between groups after training: p=1.00 | |||

| Difference between groups at 1 year: p=0.67 | |||

| ■ Aerobic capacity | |||

| Exercise: 112.9±40.1; 23.8±8.2 | |||

| Usual care: 62.8±26.3; –19.2±15.3 | |||

| Difference between groups after training: p=0.013 | |||

| Difference between groups at 1 year: p=0.010 | |||

| Adverse Events: None attributable to the intervention were reported. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ Small sample size | |||

| ■ Many dropouts | |||

| ■ Exercise group attended 76%±67%–95% of group exercise sessions and took daily walks 87%±56%–100% of the days. | |||

| Immediately postoperative | |||

| Arbane et al., 201427 | 64 Exercise intervention, 67 usual care | NSCLC | Adults after curative surgery |

| Intervention: 1 30-minute daily cycle strength and mobility training days 1–5 post-op, and home-based walking program with weekly telephone call to encourage continued 30 minutes of walking daily (walking and strength training adapted to the patient) | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 1 Time daily for 1–5 days; when at home, 1 time daily (30 minutes of walking for 4 weeks) | |||

| Measures: Quality-of-life scores (SF-36, EORTC QLQ-LC13) and quadriceps strength (kilograms force) | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score: | |||

| No significant differences between groups from baseline to 4 weeks after surgery. | |||

| ■ Quadriceps strength: | |||

| A significant difference in muscle strength was found between the groups at the 4-week postoperative assessment (p=0.04). | |||

| No other significant differences were found. | |||

| Adverse Events: There were complications from surgery, but no other adverse events were reported. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ The inpatient goals were not met because of short stay or discomfort. | |||

| ■ An airflow obstruction sub-analysis found a significant difference between groups for quality of life (p=0.01). | |||

| Arbane et al., 201137 | 27 Exercise intervention, 26 usual care | NSCLC | Adults referred for lung resection by open thoracotomy or visually assisted thoracotomy |

| Intervention: Strength and mobility training 2 times daily on days 1–5 postoperatively, and 12-week home-based program with 3 visits (once monthly) to encourage continued use of exercise program (walking and strength training adapted to patient, reaching 60%–80% of maximal heart rate) | |||

| Frequency and Duration: 5–10 Minutes to start, then adapted to individual 2 times daily for 5 days post surgery, and then for 12 weeks | |||

| Measures: 12-Week change in quality-of-life scores (EORTC QLQ-C30, global health score), and change in mean aerobic fitness (6-minute walk test in metres) and in mean quadriceps strength (magnetic stimulation of femoral nerve, kilograms) preoperatively, 5 days postoperatively, and at 12-week follow-up | |||

| Main Findings: | |||

| ■ Quality-of-life score | |||

| Exercise: 6.5; 95% CI: –7.7 to 20.7 | |||

| Usual care: 2.2; 95% CI: –5.2 to 9.6 | |||

| No significant difference were observed over time or between groups. | |||

| ■ Mean aerobic fitness | |||

| Exercise: 466.6±102.1; 336.7±84.1; 480.2±110.0 | |||

| Usual care: 455.7±98.0; 308.7±124.8; 448.2±95.1 | |||

| Repeated measures analysis, overall within-subject time effect: p<0.001; group effect, p=0.47 | |||

| Preoperatively to 5 days postoperatively (paired t-tests): inter-subject group time effect: p=0.89 | |||

| ■ Mean quadriceps strength | |||

| Exercise: 33.2±15.2; 37.6±27.1; 34.2±9.4 | |||

| Usual care: 29.1±10.9; 21.5±7.7; 26.4±9.7 | |||

| Repeated measures analysis within-subject time effect: p=0.70 | |||

| Preoperatively to 5 days postoperatively inter-subject group effect: p=0.04 | |||

| Adverse Events: Adverse events were not reported. | |||

| Comments: | |||

| ■ No adherence information | |||

| ■ No clear intervention information after 5 days postoperatively | |||

| ■ Some loss to follow-up | |||

| ■ Many participants could not complete the quadriceps strength measures because of metal implants, and many did not repeat the quadriceps strength measures. | |||

FACT-B[+4] = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast [patients with lymphedema]; CI = confidence interval; CTx = chemotherapy; FACT-G = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; SF-36 = Short Form (36) Health Survey; VO2 = volume of oxygen; ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; FACT-P = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Prostate; PORPUS = Patient Oriented Prostate Utility Scale; ACT = Adjuvant chemotherapy; EORTC = European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; QLQ-C30 = 30-question quality-of-life survey; QLQ-BR23 = 23-question breast cancer–specific quality-of-life survey; MET = metabolic equivalents; PACT = Physical Activity after Cancer Treatment; FACT-C = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Colorectal; QLQ-LC13 = 13-question module for lung cancer trials.

All systematic reviews6–21,48,49 found positive changes in both muscular and aerobic fitness (Table v). Of the sixteen rcts that measured muscular or aerobic fitness or both22,23,27,28,30,32,33,37,38,40,41,43–47, twelve found significant positive changes in the exercise groups (Table vi)22,23,27,28,30,32,37,38,41,43,44,46. One systematic review14 found substantial increases in muscular strength and endurance with resistance training for patients on androgen deprivation therapy (Table v).

Safety, Adverse Events, or Injuries

The safety of exercise for adults living with cancer is a very important outcome. Safety outcomes include measures such as the frequencies and types of adverse events during exercise sessions or whether treatment delivery or cancer-specific outcomes were negatively affected.

Two guidelines5,43 concluded that exercise is safe for people with cancer both during active treatment and after treatment. The Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre5 developed recommendations concerning the efficacy and safety of exercise treatment during cancer treatment. Based on data about the safety of exercise from a systematic literature review, no harmful effects of exercise during treatment were found. Thus, it was concluded that exercise is safe for patients undergoing treatment for cancer. The American College of Sports Medicine43 convened an expert panel to create a roundtable consensus statement about exercise for cancer survivors. After reviewing the literature, the panel concluded that exercise training is safe during and after cancer treatments. They recommended that exercises could be specifically adapted based on disease-and treatment-related adverse effects such as lymphedema. They also developed pre-exercise medical assessments to help ensure safety and to guide exercise specialists concerning exercise programs for people living with cancer.

In the systematic reviews and rcts, very few adverse events were attributable to exercise; most studies reported no adverse events at all that were attributable to exercise (Tables v and vi). Of the systematic reviews, nine6–9,13,15,16,19,21 made no mention of adverse events, two10,48 indicated that no adverse events were reported in the studies, and six12,14,17,18,20,49 indicated that adverse events had been reported in studies, but did not provide information about the events. One systematic review20 found that cardiopulmonary exercise testing was a safe, noninvasive method to measure cardiopulmonary fitness in people living with cancer, both during and after treatment.

Seventeen rcts22–24,27,29,30–33,37,39,42,45,47,51–53 found that no adverse events or side effects were attributable to the exercise program. Seven26,28,34,35,40,46,50 did not report on adverse events at all. Three rcts25,41,44 reported adverse events that were deemed not to be related to the intervention; two36,38 reported events that were attributable to the intervention (3 patients experienced muscle soreness, and 2 experienced musculoskeletal injury).

Delivery Models and Supervised Settings

Four systematic reviews8,11,15,49 detected a greater and more consistent benefit of exercise for qol and muscular and aerobic fitness when the intervention was offered in a group or supervised setting compared with a home-based or unsupervised setting (Table v). Two rcts32,36 compared various settings for interventions and found that the beneficial effects were greater when exercise was supervised, either in groups or by telephone. One rct40 found a significant linear trend between an increase in weekly metabolic equivalents of task performed and an improved qol score for all patients in the study.

Intensity Levels and Types of Exercise

Intensity Levels:

Three systematic reviews6,11,18 studied exercise intensity levels and found that studies of longer length (more weeks) and those that included at least moderate-intensity exercise were associated with improved qol and muscular and aerobic fitness (Table v). Another systematic review19 that evaluated interventions with positive results for qol found that moderate-intensity aerobic exercise programs used in those interventions resulted in a benefit for qol (Table v). Two rcts33,39 compared various exercise intensity levels and found improvements in muscular endurance and aerobic capacity for the higher-intensity groups (Table vi). One rct40 found, for all participants, a significant linear trend between an increase in weekly energy expenditure or metabolic equivalents of task performed and an improved qol score (Table vi).

Resistance Training: