Abstract

Dural lymphoma (DL) is a rare type of primary CNS lymphoma arising from the dura mater. The optimal treatment is uncertain. A retrospective review was performed on 26 DL patients. Seventeen patients underwent resection and 9 had a biopsy. 23 patients could be assessed for a response to treatment after surgery. 13 received focal radiotherapy (RT), 6 whole brain RT (WBRT), 3 chemotherapy alone and 1 chemotherapy followed by WBRT. 22 achieved complete response (CR) and one a partial response (PR). Four patients relapsed (2 local and 2 systemic). Median follow up was 64 months, with median PFS and OS not reached. Three year PFS was 89% (95% CI 0.64–0.97). All patients are alive at last follow-up, demonstrating that DL is an indolent tumor with long survival. CR is achievable with focal therapy in the majority of cases, but there is a risk for relapses and long-term follow-up is recommended.

BACKGROUND

Dural lymphoma (DL) is a rare type of primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) that arises from the dura mater and does not directly involve the brain parenchyma. The exact incidence of DL is unknown, and the published data consist of small reports and case series (1–3). DL occurs more frequently in middle aged women, in contrast to parenchymal PCNSL which is more common in men (1, 2). Due to their clinical and radiographical similarities to meningiomas or dural metastases, DLs are often misdiagnosed. (2, 4). Neuroimaging frequently identifies a single or multiple diffusely enhancing extra axial lesions with a dural tail (1). DLs can cause a variety of clinical symptoms depending on the location and size of the tumor.

Unlike parenchymal PCNSL, which is almost always a diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), DLs are usually marginal zone lymphomas (MZL) (5, 6). The cytomorphology of the neoplastic cells have a typical monocytoid appearance and at times plasmacytic differentiation, characteristic of non-CNS MZLs. Mature plasma cells can be numerous, some of which may contain Dutcher bodies. Occasional scattered large lymphoid cells are seen. The proliferation index, as measured by Ki-67 (MIB1), is usually very low, frequently less than 5%. However, cases of higher grade lymphomas arising from the cerebral dura and more frequently from the spinal dura have been described (7–9).

The marginal zone DLs have an indolent course and favorable response to treatment. However, because of the rarity of the disease and the potential for direct CNS infiltration, the optimal therapeutic approach has not been established. Most patients are treated with surgical resection, radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. The treatment choice has depended on staging and the presence of leptomeningeal involvement which has been reported in up to 62.5% of patients in one series (1). However, most patients with DL respond well to focal lower dose radiotherapy (RT) and commonly achieve a complete response (CR), including those with leptomeningeal disease (1, 10). The risk of systemic relapse was previously reported to be high, up to 38% in one study(1), but the true risk as well as whether chemotherapy reduces the risk for systemic relapse are unknown. In this study, we report our experience with twenty six patients with DL to clarify the clinical course and treatment response of this rare disease.

METHODS

We have performed a retrospective review of patients with DL seen at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the University of Miami Health System between 1993 and 2015. Patients were identified through institutional databases at both sites and were included in this report if they met the following criteria: 1) clinical presentation of a dural mass and no evidence of primary parenchymal brain involvement, 2) brain imaging demonstrating an extra-axial mass arising from the dura mater, 3) pathologic confirmation of lymphoma, 4) primary neurological presentation. Our review identified twenty six patients with DL, five of whom were reported previously (1). Medical records were reviewed to determine patient characteristics, pattern of care and outcome. All patients underwent systemic staging evaluation, including brain MRI, total spine MRI, computerized tomography of chest, abdomen and pelvic and/or FDG-PET, bone marrow biopsy, ophthalmologic examination with slit lamp, HIV serology and lumbar puncture with cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) analysis of cell count, protein level, glucose level, cytology and flow cytometry. Not all these tests were available for review in every patient, although 25 (96%) patients had a comprehensive systemic staging evaluation done. All available baseline MRIs were reviewed by a board certified neuroradiologist to identify radiographic features of dural lymphoma. When available at initial brain MRI, diffusion was quantified on the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps placing multiple (3–4) small fixed diameter (25–50 mm2) regions-of-interest within the mass and recording the most abnormal measurement (11). Radiographic response was based on review of the post-treatment imaging and neuroradiology report. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to examine survival from the date of diagnosis to date of death or last follow-up. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at both institutions.

RESULTS

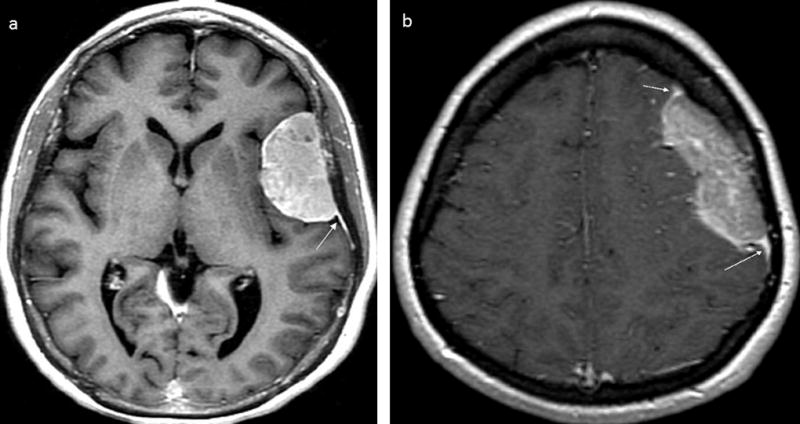

The median age at tumor diagnosis of our 26 patients was 50 years (range, 30–77 years) and 20 (74%) were women (Table 1). The most frequent symptoms were seizures (41%), headache (33%) and cranial nerves palsies (30%). Median time from initial symptoms to tumor diagnosis was 8 weeks (range, 1 to 90 weeks). All lesions were exclusively extra-axial, and tumors presented in the frontal lobe in 6 (23%) patients, temporal lobe in 4 (15%), occipital lobe in 3 (12%), the cavernous sinus in 3 (12%), the cerebellopontine angle in 2 (8%), the falx cerebri in one (4%) and was suprasellar in one (4%) patient. Six patients presented with multifocal disease. Pre-operative MRI was available for our review in 17 patients. Sixteen (95%) had lesions with an enhancing dural tail. In 10 (63%) of these 16 patients, lymphoma enhancement intensity was less than that of the enhancing dural tails (Figure 1). Underlying vasogenic edema was seen in 56% of patients, hyperostosis/erosion of the contiguous bone in 3 (18%), calcification in one (6%) and central vascular pedicle in one (6%). In 6 patients, diffusion was available for quantification using apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps. The median ADC was 0.598 × 10−3mm2/s (range, 0.322–0.833).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with marginal zone dural lymphoma.

| Age at diagnosis (yrs), Sex |

Symptoms at onset |

Lesion location | No. of lesions |

Surgery | Chemotherapy | Radiation Therapy |

Outcome* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47, M | Generalized tonic clonic seizure | L tentorium | Single | Partial resection | None | Focal RT (30 Gy) | CR, 12.1 yrs |

| 66, M | Seizures, progressive gait disorder | Left fronto-parietal | Single | Biopsy | Rituximab and Bendamustine x5 cycles | None | CR, 1.1 yrs |

| 41, F | Headache, focal seizures, R visual field cut | L parieto-occipital | Single | GTR | None | Focal RT (36 Gy) | CR, 7.2 yrs |

| 51, F | long h/o headache with new worsening | L frontal | Single | Partial resection | None | WBRT (24 Gy) followed by cone down to frontal lobe area (12 Gy) | CR, 11.3 yrs |

| 49, F | Focal L face numbness and paresthesias L ear tinnitus and otalgia | L tentorium (compressing L brainstem and cerebellar hemisphere) | Single | Partial resection | None | Focal RT (30Gy) | CR, 6.8 yrs |

| 69, F | Walking difficulty | L temporo-parietal convexity | Single | Biopsy | R-CHOP x6 cycles followed by maintenance Rituximab x8 cycles every 3 months | None | CR, 8.6 yrs |

| 51, F | Seizure, L homonymous hemianopsia | R occipital | Single | Biopsy | None | WBRT (24 Gy) followed by a boost to area of enhancement (15 Gy) | CR, 5.7 yrs |

| 59, M | Headache | R temporal, R frontal | 2 lesions | GTR of both lesions | NA | NA | NA |

| 49, F | Focal seizures | R fronto-parietal | Single | Partial resection | None | WBRT (29 Gy) followed by boost to the right fronto-parietal area (9 Gy) | CR, 4.6 yrs |

| 72, F | Generalized tonic clonic seizure | Long lesion extending along the falx cerebri | Single | Partial resection | NA | NA | NA |

| 33, F | Generalized tonic clonic seizure | L frontal and L parietal | 2 lesions | Resection of the parietal lesion only | None | WBRT (24 Gy) followed by boost to both lesions (12 Gy) | CR, 0.9 yr |

| 65, F | Headache, L facial weakness | R temporo-parietal | Single | Partial resection | HD-MTX, IT MTX, vincristine, procarbazine, HD cytarabine | WBRT (45 Gy) | CR, 17.2 yrs |

| 39, F | Vision loss, focal R sided paresthesias | L frontal, R sphenoid region/orbital apex | 2 lesions | Partial resection of sphenoid lesion only | None | WBRT (18 Gy) and focal RT (12 Gy) | CR, 9 months, POD (systemic) SD, 8 yrs |

| 49, F | Headache, seizures, visual loss | R temporal, R frontal | 2 lesions | Biopsy | None | WBRT (30 Gy) | CR, 3.1 yrs POD (systemic) CR, 2 yrs |

| 39, F | Headache | R frontal | Single | Partial resection | None | Focal RT (36 Gy) | CR, 1.3 yrs |

| 30, F | Facial pain | Cavernous sinus | Single | Partial resection | None | Focal RT (16 Gy at diagnosis)/36 Gy at POD) | PR, 1.8 yrs, POD CR, 9 yrs |

| 67, F | Headache | R occipital | Single | Partial resection | None | NA | NA |

| 47, M | Seizures | L frontal | Single | Biopsy | None | Focal RT (36 Gy) | CR, 5.6 yrs |

| 34, M | Seizures | R temporal | Single | GTR | None | Focal RT (36 Gy) | CR, 5.3 yrs |

| 67, M | Seizures | R frontal | Single | Biopsy | None | Focal RT (30 Gy) | CR, 4.7 yrs |

| 51, F | Focal paresthesias and numbness | L cavernous sinus | Single | Biopsy | None at initial diagnosis. Rituximab/ bendamustine at POD | Focal RT (30 Gy) | CR, 3 yrs, POD CR, 15 months |

| 57, M | Seizures, headache | R temporal | Single | GTR | None | Focal RT (30 Gy) | CR, 2.5 yrs |

| 59, F | Headache | Suprasellar region | Single | Biopsy | None | Focal RT (36 Gy) | CR, 1.9 yrs |

| 48, F | Cranial nerve palsy | Cavernous sinus (bilateral) | Multiple | Biopsy | Rituximab at initial diagnosis | Patient refused RT | CR, 10 months |

| 77, F | Gait disturbance | R cerebello-pontine angle | Single | GTR | None | Focal RT (30 Gy) | CR, 8 months |

| 50, F | Cranial nerve palsy | Cavernous sinus | Single | Partial resection | None | Focal RT (30 Gy) | CR, 2 months |

FIGURE 1. Axial post-gadolinium T1-weighted imaging of dural masses.

(a) Brain MRI image showing a meningioma with avid enhancement including dural tail and characteristic hyperostosis of the overlying calvarium. (b) Brain MRI image showing a DL with lesser enhancement than the dural tail; it also shows an irregular medial border of DL which is atypical of meningioma. White arrows denote dural tails.

During staging, one patient was found to have systemic disease at diagnosis. Work-up for ophthalmologic disease was negative in all 20 patients tested. One of 22 patients who had CSF evaluation was diagnosed with leptomeningeal disease with lymphoma cells detected in CSF. One patient was HIV positive at the time of DL diagnosis.

Seventeen (65%) patients underwent tumor resection as the lesion was thought to be a meningioma; five (30%) had a gross total and 12 (70%) a partial resection. Nine (35%) patients underwent biopsy. Pathology was reviewed in all cases and showed low grade small lymphoma cell infiltrates compatible with MZL (Figures 2 and 3), with distinct pathologic findings. All cases showed a diffuse growth pattern. The neoplasms were often adherent to prominently sclerotic meningeal tissue. The background frequently contained areas with sclerosis as well as frequent small to intermediate blood vessels with hyalinized walls. Hemorrhage could be seen in few cases, and in long standing cases, hemosiderin-laden macrophages were present. These neoplasms usually had a pushing border with the adjacent brain parenchyma. Neoplastic infiltrate expanding the Virchow’s spaces was occasionally seen in blood vessels located within the brain parenchyma.

FIGURE 2. Marginal zone dural lymphoma, pathologic features.

(a) Low power view of a dura biopsy demonstrating extensive hyalinization and fibrosis (H&E, 4×). (b) Atypical, monocytoid cells surrounding and infiltrating meningeal tissue (H&E, 20×) (c) Tumor abuts the brain parenchyma with a pushing border (large arrow). The blood vessel demonstrates prominent lymphocytic infiltrate within the Virchow-Robin space (thin arrow). (d) Higher power demonstrating that the neoplastic cells have a plasmacytic differentiation. (e) Atypical monocytoid cells with intervening blood vessels demonstrating extensive hyalinization (H&E, 10×). (f) Higher magnification of neoplastic monocytoid cells with surrounding blood vessels demonstrating extensive hyalinization (H&E, 40×).

FIGURE 3. Marginal zone dural lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation, immunohistochemistry profile.

(a) Brain parenchyma with vessel demonstrating prominent lymphocytic infiltrate within the Virchow-Robin space. (b) CD20 demonstrates few cells with expression. (c) CD5 highlights numerous T cells within Virchow-Robin space. (d) Lambda by in situ hybridization demonstrates clonal plasma cell differentiation. (e) Kappa by in situ hybridization is negative. (f) Ki67 proliferation index is less than 5%.

Cytologically, the lymphoma cells ranged from the monocytoid cells (small lymphocytes with minimal cytologic atypia and clearing of the cytoplasm), centrocytes to those with more plasmacytic differentiation. In some cases mature plasma cells were numerous, some of which contained Dutcher bodies. Occasional scattered large lymphoid cells were frequently seen but none of the cases show diffuse large cell transformation.

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on all cases. The antibody panel used was variable over time. All cases expressed CD20 although the lymphoplasmacytoid cells as well as the plasma cells were usually CD20 negative but CD79a positive. Plasma cells were monoclonal for kappa or lambda light chains in a subset of the cases. The tumor cells were usually positive for BCL-2 and were negative for CD5, CD10, BCL-6 and LEF1. EBER was negative in the cases tested. The proliferation index, as demonstrated by the Ki-67 (MIB1 antibody), was low in all the cases assessed (median: 5%; range: <5% to 10%).

All patients received further treatment after surgery. Three (11%) patients received treatment outside of our Centers, and no follow-up data were available for review. Of the 23 patients who were treated at our Centers, nineteen (83%) received RT alone. Thirteen received focal intensity-modulated (IM) RT (16 to 36 Gy in 9 to 20 fractions) and 6 whole brain (WB) RT (36 to 39 Gy in 20 to 26 fractions), 3 of whom had multifocal disease. Three (12%) received systemic therapy (one due to systemic disease and two patients because they refused RT) that consisted of rituximab; rituximab and bendamustine; and rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (R-CHOP) in one patient each. One patient received methotrexate, procarbazine and vincristine (MPV) followed by WBRT (45 Gy in 25 fractions); this patient was treated in 1994 and was the only patient who developed significant treatment related leukoencephalopathy.

One patient had systemic disease identified at diagnosis. This patient presented with a left temporal dural lesion, bilateral lung nodules and left para-aortic retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy and was treated with R-CHOP followed by maintenance Rituximab. The patient achieved a CR and remains disease free 9 years after her diagnosis.

One patient had leptomeningeal involvement (LMD) at diagnosis. This patient presented with a left fronto-parietal dural lesion, and leptomeningeal involvement by CSF analysis (cytology and flow cytometry); he was treated with rituximab and bendamustine for 5 cycles. The patient achieved CR and remains disease free 14 months after initial diagnosis.

Of the 23 patients, 22 had a CR after initial therapy. One patient was started on focal IMRT but discontinued treatment after receiving 16 Gy of a planned 36 Gy, achieving a partial response and developing disease progression at the same site 18 months later. This patient completed RT at tumor progression, had a CR, and has not relapsed (follow-up 108 months). Three patients relapsed after achieving an initial CR. One had local recurrence at the site of initial tumor presentation after focal RT 3060 cGy and received rituximab plus bendamustine, achieved a CR and is disease free for 15 months. The other 2 patients developed systemic progression. Both were initially treated with 3000cGy WBRT plus a 1200 cGy boost. One patient had disease involving the left axilla and chest wall and was treated with RT. This patient achieved a CR and has remained disease free for 24 months. The other patient had histologically confirmed lung involvement and was managed by expectant monitoring without further disease progression for 8 years after developing pulmonary disease.

For the 23 patients with data on treatment, the median follow-up was 64 months (range, 2 to 209 months). Median progression free survival (PFS) and median overall survival have not been reached (Figure 4). Three-year PFS was 89% (95% CI 0.64–0.97) and 5-year PFS was 76% (95% CI 0.49–0.90). All patients are alive at the time of last follow-up.

FIGURE 4. Progression free survival and overall survival for marginal zone dural lymphoma patients.

(a) Progression free survival. (b) Overall survival. N: 23.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, these 26 patients represent the largest published series on DL. DL is more common in middle-aged women, and the most frequent symptoms at presentation are seizure and headache (1, 2). Almost 70% of our patients underwent resection as the lesion was thought to be a meningioma. We reviewed pre-operative MRIs in an effort to identify radiographic features for this patient population. Dural tails were observed in 95% of patients. In ~60% of the patients, we observed that lymphoma enhancement was less intense than enhancement of the reactive dural tail. This differs from meningioma, where the intensity is equal. The ADC measurements in the subset of patients with evaluable tumors confirmed restricted diffusion comparable to what has been reported in PCNSL (0.55–0.58 x10-3mm2/s), and lower than those reported in meningioma (0.85–0.96 x10-3mm2/s) (12–14). Diffusion may be variable in atypical or malignant meningiomas with lower ADC values, but diffusion measurements may be helpful in differentiating DL from meningioma (15). In addition, underlying vasogenic edema was seen in 56% of patients, which is an uncommon finding in typical grade I meningiomas.

DL may rarely be a presenting feature of systemic lymphoma, as seen in one of our patients. Systemic staging is critical as positive findings have important therapeutic implications. Our patient with systemic disease achieved CR with systemic chemotherapy (R-CHOP followed by maintenance Rituximab) and has remained disease free 9 years after her diagnosis.

Pathology in all 26 patients was compatible with MZL. These lymphomas diffusely infiltrate and often adhere to sclerotic meningeal tissue. The background frequently contains areas with sclerosis as well as small to intermediate blood vessels with hyalinized walls. Hemorrhage is often present, and in long standing cases, hemosiderin-laden macrophages can be abundant. Immunophenotypically the lymphoma cells express pan-B cell markers, CD20, CD22, CD19 as well as CD79a and are PAX-5 positive. The lymphoplasmacytoid cells as well as the plasma cells are usually CD20 negative but CD79a positive. Plasma cells can exhibit monoclonality for kappa or lambda light chains. The tumor cells are usually positive for BCL-2 and 50% of cases are positive for CD43. They are frequently negative for CD10, BCL-6, LEF1 and EBER; CD5 can be positive in a subset of cases.

Although no standard therapy is available for DL, for extranodal MZL limited to a single site, local treatment such as surgery followed by focal RT are effective and CR is usually achieved. The optimal radiation dose is less well defined, although relatively low doses of radiotherapy produce excellent results in patients with a single disease site. The low dose radiation that has been recently recommended is 24 Gy to the whole brain if more than a single dural based lesion is present with boosting of the involved sites to 36 Gy with a total dose recommendation of 30 to 36 Gy in localized tumors(16). High-dose methotrexate followed by WBRT should be avoided when possible due to the high risk for leukoencephalopathy and cognitive decline, as previously reported in PCNSL, and given the long survival of patients with DL.

We observed disease progression in 4 patients (16%), one of whom had an incomplete course of treatment. Two patients had local and two had systemic recurrence. Of the two patients with local recurrence one received sub-optimal focal RT and only one developed local recurrence at the site of previous tumor after achieving CR after initial RT. In our series, we try to have the volume of disease encompassed. As the volume increases, we tend to start with whole brain and then reduce to the bulk site. However, when volume is not very large, we tend to treat the contrasted disease and chase dural thickening, allowing a margin of 1.5 cm for clinical target volume (CTV) and another 0.5 cm for planning target volume (PTV). Systemic relapse without local progression suggests the presence of microscopic systemic disease at presentation, as has been observed in the natural history of MZL of the ocular adnexa (17). These recurrences occurred within 38 months from initial DL diagnosis, and both patients responded to subsequent therapy and are alive at 2 and 8 years of follow-up.

In conclusion, we demonstrate the indolent nature of MZL of the dura, characterized by long survival and low lymphoma-attributed mortality, in contrast to the prognosis and disease progression of PCNSL. Systemic and neurologic staging are needed at diagnosis, and DL may harbor a risk for focal or systemic relapses several years after diagnosis and treatment. Long-term follow-up is recommended even in those patients who achieved CR after initial treatment.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Iwamoto FM, DeAngelis LM, Abrey LE. Primary dural lymphomas: A clinicopathologic study of treatment and outcome in eight patients. Neurology. 2006;66:1763–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000218284.23872.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tu PH, Giannini C, Judkins AR, Schwalb JM, Burack R, O'Neill BP, et al. Clinicopathologic and genetic profile of intracranial marginal zone lymphoma: a primary low-grade CNS lymphoma that mimics meningioma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5718–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.17.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kudrimoti JK, Gaikwad MJ, Puranik SC, Chugh AP. Primary dural non-hodgkin's lymphoma mimicking meningioma: A case report and review of literature. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11(3):648. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.146112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chourmouzi D, Potsi S, Moumtzouoglou A, Papadopoulou E, Drevelegas K, Zaraboukas T, et al. Dural lesions mimicking meningiomas: A pictorial essay. World J Radiol. 2012;4(3):75–82. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v4.i3.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swerdlow SHCE, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW. WHO Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphid Tissues. Lyon. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tandon BPL, Gao J, Nelson B, Ma S, Rosen S, Chen YH. Nuclear overexpression of lymphoid-enhancer-binding factor 1 identifies chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma in small B-cell lymphomas. Modern Pathology. 2011;24:1433–43. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miranda RN, Glantz LK, Myint MA, Levy N, Jackson CL, Rhodes CH, et al. Stage IE Non Hodgkin's Lymphoma Involving the Dura. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:254–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mneimneh WS, Ashraf MA, Li L, El-Kadi O, Qian J, Nazeer T, et al. Primary dural lymphoma: a novel concept of heterogeneous disease. Pathol Int. 2013;63(1):68–72. doi: 10.1111/pin.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdullah S, Morgensztern D, Rosado M, Lossos IS. Primary lymphoblastic B-cell lymphoma of the cranial dura mater: a case report and review of the literature. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2009;46(11):1651–7. doi: 10.1080/10428190500215126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puri DR, Tereffe W, Yahalom J. Low-dose and limited-volume radiotherapy alone for primary dural marginal zone lymphoma: treatment approach and review of published data. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71(5):1425–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.SG W, S C, G J, P L, M L, DL K, et al. Relative cerebral blood volume measurements in intracranial mass lesions: interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility study. Radiology. 2002;224(3):797–803. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2243011014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mabray MCCB, Villanueva-Meyer JE, Valles FE, Barajas RF, Rubenstein JL, Cha S. Performance of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Values and Conventional MRI Features in Differentiating Tumefactive Demyelinating Lesions From Primary Brain Neoplasms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(5):1075–85. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toh CHCM, Wong AM, Wei KC, Wong HF, Ng SH, Wan YL. Differentiation between classic and atypical meningiomas with use of diffusion tensor imaging. AJNR. 2008;29(9):1630–5. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stadnik TW1 CC, Michotte A, Shabana WM, van Rompaey K, Luypaert R, Budinsky L, Jellus V, Osteaux M. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of intracerebral masses: comparison with conventional MR imaging and histologic findings. AJNR. 2001;22(5):969–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filippi CGEM, Uluğ AM, Prowda JC, Heier LA, Zimmerman RD. Appearance of meningiomas on diffusion-weighted images: correlating diffusion constants with histopathologic findings. AJNR. 2001;22(1):65–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yahalom J, Illidge T, Specht L, Hoppe RT, Li YX, Tsang R, et al. Modern radiation therapy for extranodal lymphomas: field and dose guidelines from the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92(1):11–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayraktar S, Bayraktar UD, Stefanovic A, Lossos IS. Primary ocular adnexal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALT): single institution experience in a large cohort of patients. Br J Haematol. 2011;152(1):72–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]