Abstract

Introduction: In recent research, orally administered cannabidiol (CBD) showed a relatively high incidence of somnolence in a pediatric population. Previous work has suggested that when CBD is exposed to an acidic environment, it degrades to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and other psychoactive cannabinoids. To gain a better understanding of quantitative exposure, we completed an in vitro study by evaluating the formation of psychoactive cannabinoids when CBD is exposed to simulated gastric fluid (SGF).

Methods: Materials included synthetic CBD, Δ8-THC, and Δ9-THC. Linearity was demonstrated for each component over the concentration range used in this study. CBD was spiked into media containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Samples were analyzed using chromatography with UV and mass spectrometry detection. An assessment time of 3 h was chosen as representative of the maximal duration of exposure to gastric fluid.

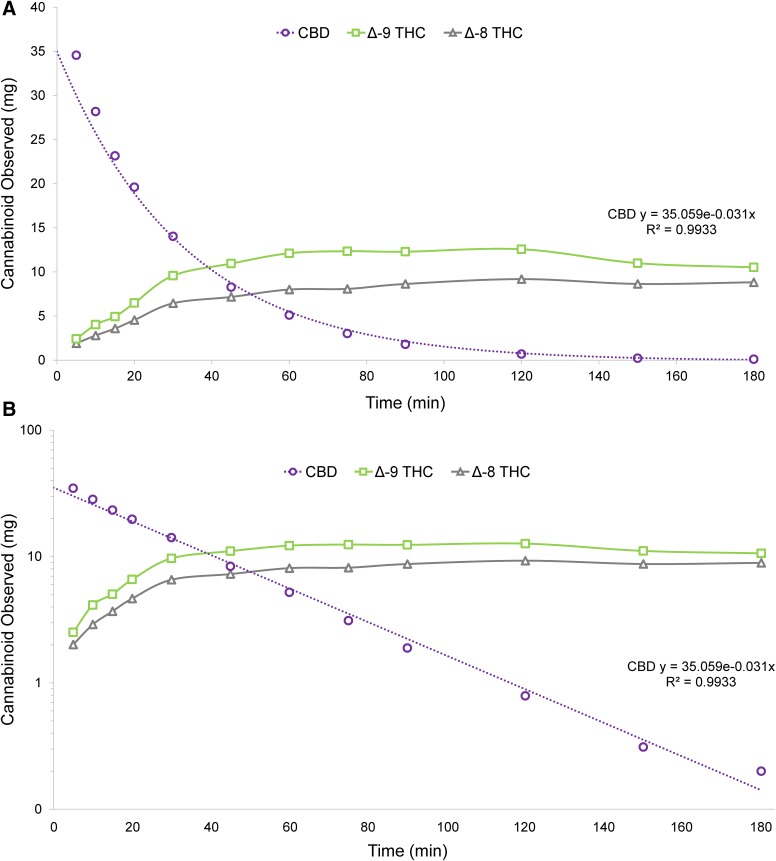

Results: CBD in SGF with 1% SDS was degraded about 85% after 60 min and more than 98% at 120 min. The degradation followed first-order kinetics at a rate constant of −0.031 min−1 (R2=0.9933). The major products formed were Δ9-THC and Δ8-THC with less significant levels of other related cannabinoids. CBD in physiological buffer performed as a control did not convert to THC. Confirmation of THC formation was demonstrated by comparison of mass spectral analysis, mass identification, and retention time of Δ9-THC and Δ8-THC in the SGF samples against authentic reference standards.

Conclusions: SGF converts CBD into the psychoactive components Δ9-THC and Δ8-THC. The first-order kinetics observed in this study allowed estimated levels to be calculated and indicated that the acidic environment during normal gastrointestinal transit can expose orally CBD-treated patients to levels of THC and other psychoactive cannabinoids that may exceed the threshold for a physiological response. Delivery methods that decrease the potential for formation of psychoactive cannabinoids should be explored.

Key words: : cannabidiol, degredation, drug discovery, gastric fluid, kinetics, THC

Introduction

The flowering plants of the genus Cannabis, which mainly comprises the sativa and indica species,1,2 have been recognized for medical treatment for millennia. Although Cannabis contains nearly 500 compounds from 18 chemical classes, its physiological effects derive mainly from a family of naturally occurring compounds known as plant cannabinoids or phytocannabinoids. Of the more than 100 phytocannabinoids that have been identified in Cannabis,3 among the most important and widely studied are its main psychoactive constituent, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC),4 and the most important nonpsychoactive component, cannabidiol (CBD).5 Other biologically active phytocannabinoids that have been isolated in Cannabis include Δ8-THC, cannabinol, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin, and cannabidivarin.2,6

THC and CBD produce a wide range of pharmacological effects by interacting with an endogenous lipid-signaling network known as the endocannabinoid system, specifically with two G-protein-coupled receptors known as cannabinoid 1 (CB1) and cannabinoid 2 (CB2).7 CB1 receptors are densely expressed in the brain8 and they have been detected in dorsal primary afferent spinal cord regions and spinal interneurons,9–11 whereas CB2 receptors are located primarily in the tissues of the immune system (macrophages), as well as in non-neuronal cells, such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia.12 As a result of the wide distribution of these receptors, cannabinoids are thought to play a role in an array of physiological and pathophysiological processes.8,9,13,14

THC is considered a partial agonist at CB1 and CB2 receptors.5,7 Its activity at these receptors has been associated with numerous physiological effects, such as inhibiting adenylate cyclase activity and Ca2+ influx, decreasing formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate and protein kinase A activity, activating inwardly rectifying potassium channels and stimulating the mitogen-activated protein kinase-signaling cascades.12,15 CBD has an affinity for CB1 and CB2 receptors in the micromolar range5,7,16 and has been described as a noncompetitive inverse agonist (e.g., potentially inhibiting the activity of cannabinoid agonists).7 However, the pharmacodynamic profile of CBD includes a variety of effects, including blocking the equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT1) and enhancing functionality of the 5-HT1a receptor, glycine receptors, the transient receptor potential of vanilloid type-1 channel, and the melastatin type 8 channel.7 In addition, CBD has been shown to regulate the intracellular effects of calcium and ligand binding to several receptors, including the G-protein-coupled receptor GPR55.2 Functionally, CBD can exert a range of anti-inflammatory effects, including attenuation of endothelial cell activation, chemotaxis of inflammatory cells, suppression of T-cell macrophage reactivity, and induction of apoptosis of T cells.2,7

Well-controlled studies have begun to clarify the therapeutic potential of the phytocannabinoids. With THC, for example, clinical and preclinical data support its ability to treat pain, reduce nausea and vomiting, and increase appetite.1,7,17 CBD has shown antiemetic, anticonvulsant, anti-inflammatory, and antipsychotic properties in animal studies.18–21 Clinical trials have been conducted with a variety of disease states, among them multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia, bipolar mania, social anxiety disorder, insomnia, Huntington's disease, and epilepsy.16 Overall, CBD has a positive safety profile,22 and there have been encouraging results in the treatment of patients with inflammation, diabetes, cancer, affective disorders, neurodegenerative diseases,23 and epilepsy.2,18,24 These clinical studies with CBD, particularly in patients with epilepsy, have generated interest in its medical application and attracted attention in the popular media.25

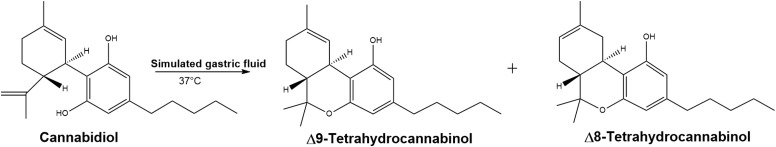

In recent epilepsy research, pediatric subjects receiving orally administered CBD showed a relatively high incidence of adverse events (≤44%), with somnolence (≤21%) and fatigue (≤17%) among the most common.26,27 If CBD is nonpsychoactive, we wondered whether these responses might be associated with a clinical manifestation of findings from experimental work,28 suggesting that when CBD is degraded in an acidic environment, it rapidly cyclizes to Δ9-THC and other psychoactive cannabinoids. To test the hypothesis that CBD might be converted to THC in the acidic environment of the stomach (Fig. 1), an in vitro study was completed by evaluating the formation of psychoactive cannabinoids as possible degradation products of oral CBD under simulated gastric and physiological conditions. Due to the limited aqueous solubility of CBD, an approach to improve the solubility was determined. The approach recommended in United States Pharmacopeia (USP)29 to use a surfactant was implemented and it was found that 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was required. Samples from the study were assayed through ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) with UV and tandem mass spectroscopy detection (LC/MS/MS) to confirm the appropriate molecular weight. Reference standards for CBD, Δ8-THC, and Δ9-THC were used in this study.

FIG. 1.

Psychoactive products of acid-catalyzed cyclization of CBD in the presence of SGF at 37°C. CBD, cannabidiol; SGF, simulated gastric fluid.

Materials and Methods

Materials included synthetic CBD (99% purity; Zynerba Pharmaceuticals, Lot: MG-24-156 R2-B), Δ8-THC (100% purity; Cayman Chemicals, Lot: 0458238-2), and Δ9-THC (100% purity; Cayman Chemicals, Lot: 0459902-3). Samples were analyzed on a Waters Acquity H Class UPLC system with UV detection followed by analysis through a Waters Acquity tandem quadrupole mass spectrometry (TQD MS/MS) detector. CBD stability studies in simulated gastric fluid (SGF) and physiological buffer [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid; HEPES] were performed in a USP Apparatus II dissolution bath (Distek model 2100B). UPLC and MS method parameters for the stability studies and sample analysis are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Conditions for the dissolution apparatus are listed in Table 3.

Table 1.

Conditions and Set Points for the Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography

| Condition | Set point |

|---|---|

| Mobile phase A | 2 mM ammonium formate, pH 4.8 |

| Mobile phase B | Methanol |

| Mobile phase ratio | 30:70 A:B |

| Column | Waters HSS C18 50×2.1 mm, 1.8 μm |

| Flow rate | 0.5 mL/min |

| Wavelength | 222 nm |

| Column temperature | 50°C |

| Injection volume | 10 μL |

HSS, high-strength silica.

Table 2.

Settings for the Tandem Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry and Multiple Reaction Monitoring

| TQD MS/MS | |

|---|---|

| Ionization mode | ESI positive |

| Capillary voltage | 3.5 kV |

| Cone voltage | 30–35 V |

| Desolvation gas temperature | 250°C |

| Desolvation gas flow | 500 L/h |

| Source temperature | 150°C |

| Cone gas flow | 50 L/h |

| Mass scan range | 150–650 Da |

| MRM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor ion (m/z) | Product ion (m/z) | Dwell time (sec) | Cone voltage (V) | Collision energy (V) | Use |

| 315.2 | 193.2 | 0.200 | 35 | 20 | Quantifier |

| 315.2 | 259.3 | 0.200 | 35 | 20 | Qualifier |

ESI, electrospray ionization; MRM, multiple reaction monitoring; TQD MS/MS, tandem quadrupole mass spectrometry.

Table 3.

Conditions and Set Points for the Dissolution Bath

| Apparatus | USP II, paddles |

|---|---|

| Paddle speed | 125 rpm |

| Temperature | 37.0°C |

| Time points—SGF (min) | 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 120, 150, 180 |

| Time points—HEPES (min) | 5, 10, 15, 20 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 240, 300, 360 |

HEPES, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid; SGF, simulated gastric fluid; USP, United States Pharmacopeia.

UPLC with UV and MS/MS analyses of SDS-containing solutions

Linearity was assessed for CBD, Δ8-THC, and Δ9-THC by calculating the regression line, expressed by the coefficient of determination (R2), and evaluated from ∼0.1% to 120% of the target CBD sample concentration (8.0 μg/mL), which is equivalent to concentrations ranging from 0.008 to 9.6 μg/mL for each component. The UV response was used for quantification.

Incubation buffers and protocol

A stock solution of ∼40 mg/mL CBD was prepared in methanol. Using USP dissolution procedure guidance,29 1% SDS was added to media to solubilize 1.0 mL of the 40 mg/mL CBD stock solution; the resulting incubation media contained 0.2% methanol. CBD-containing solutions were prepared in amber glassware, amber dissolution vessels were used in the dissolution bath, and all sampling was performed under ultraviolet-filtered yellow lighting to protect solutions from light. Incubation studies were carried out in two media: one SGF and one simulating a physiological buffer.

SGF with 1% SDS was prepared by adding ∼10 g of SDS (Ultra Pure; MP Chemicals, lot: M9655) to 1 L of SGF prepared from enzyme-free concentrate (Ricca; pepsin free lot: 4505367), equivalent to 0.1 M as hydrochloric acid and 0.2% sodium chloride.

Physiological buffer with 1% SDS was prepared similarly by adding SDS to 1 L of HEPES buffer, pH 7.4 (HEPES salt, Fisher, Hank's balanced salts; Sigma).

At T=0 min (baseline), 1.0 mL of CBD stock solution in methanol (equivalent to 40 mg CBD) was spiked into separate vessels containing 500 mL of either SGF or HEPES buffer, and the paddles were started. At each time point, 1.0 mL of solution was withdrawn, and the amount of medium withdrawn from the test vessel was replaced with an equal volume of preheated medium. A maximum 3-h assessment time for SGF and 6-h assessment time for HEPES buffer exposure were chosen to nominally represent the maximal time of exposure of the substrate to the environment.

Results

Cannabinoid assay

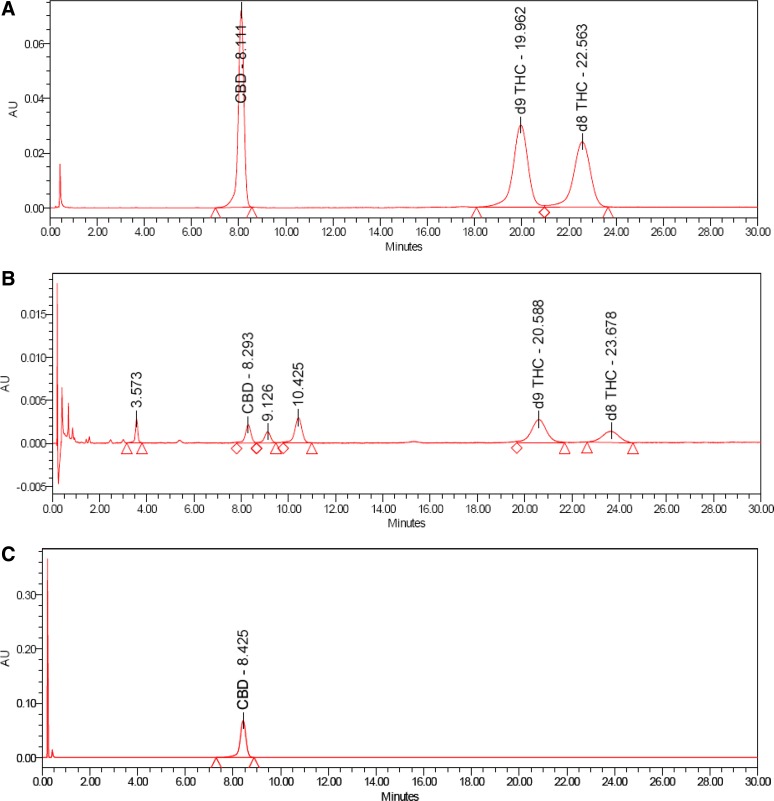

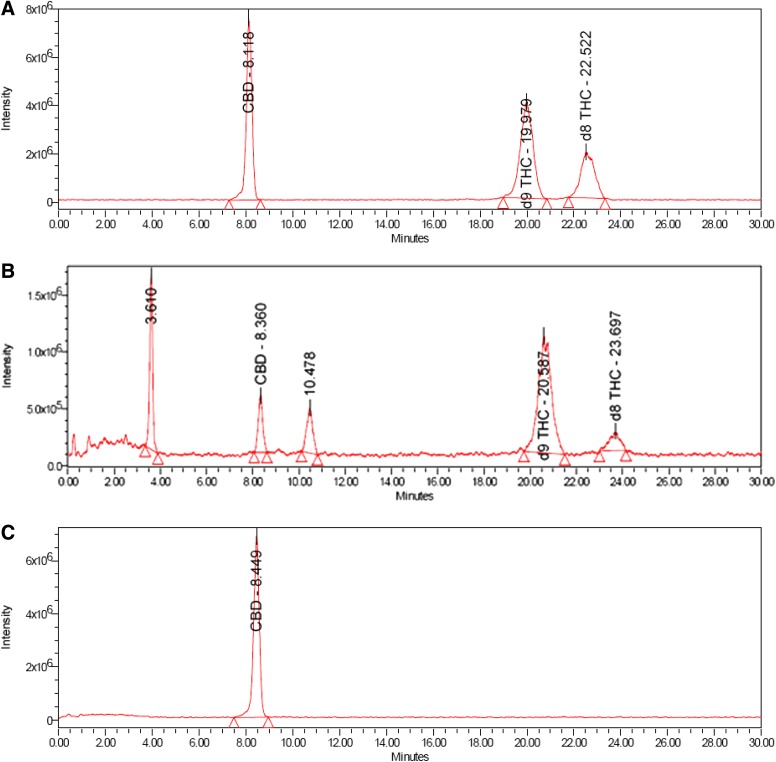

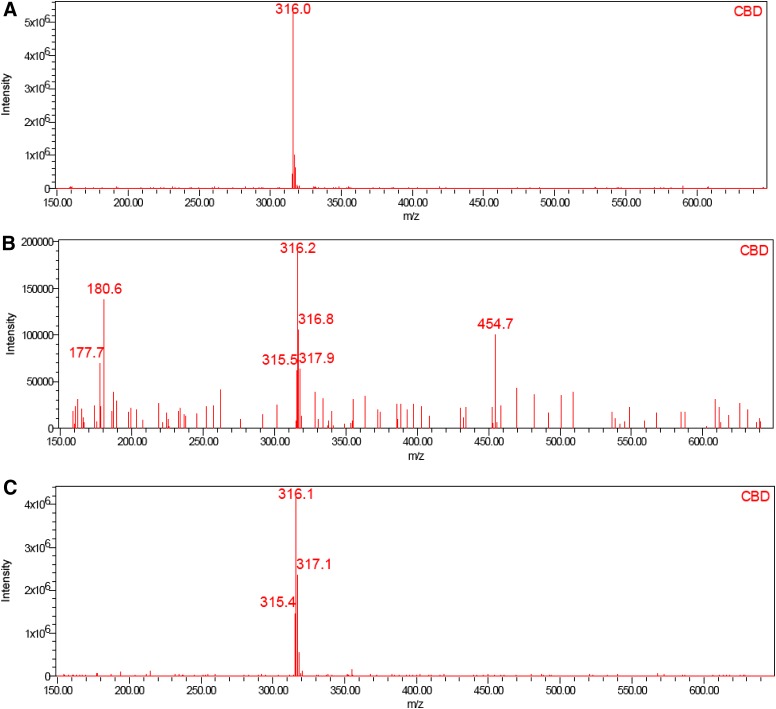

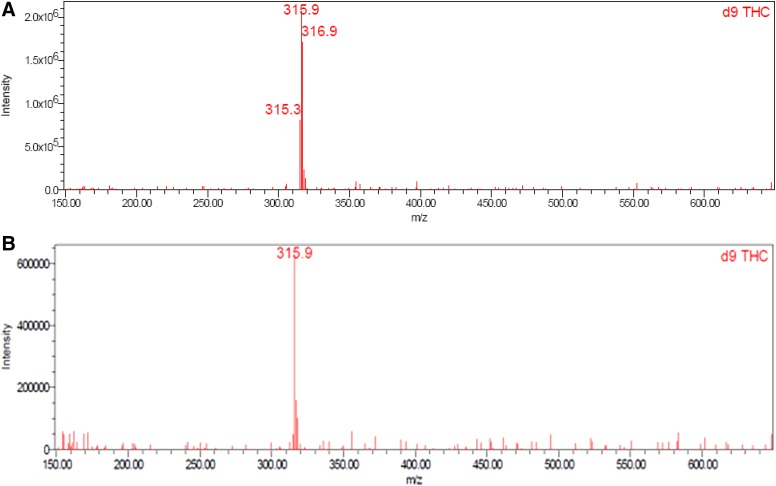

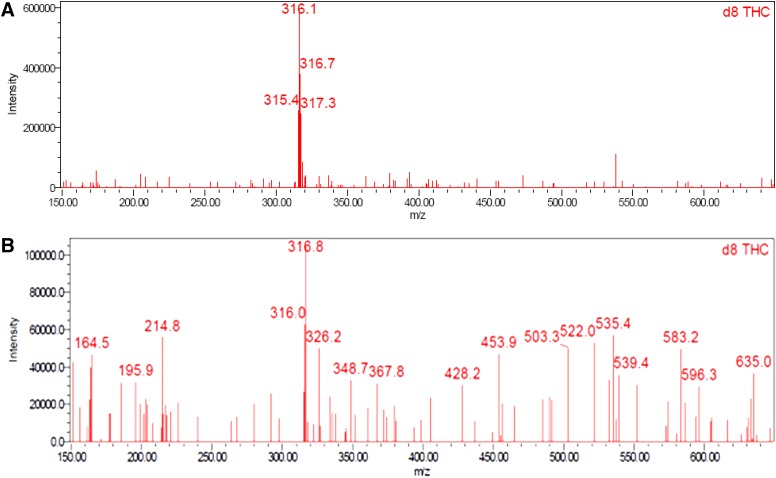

Good linearity by UPLC with UV detection was observed over the concentration range of 0.008 to 9.6 μg/mL for CBD (R2=1.0000, m=145,966, b=−837), Δ8-THC (R2=1.0000, m=103,951, b=−1448), and Δ9-THC (R2=0.9999, m=125,280, b=−2735); y-intercepts <1% of the 100% response were obtained for each component. CBD, Δ8-THC, and Δ9-THC were identified by comparing the UV and mass spectra of the peaks in the SGF with the corresponding spectra of peaks in the working standard. No interference was observed in either the SGF or HEPES buffer. Excellent analyte separation was seen with the UPLC method (Figs. 2 [UV] and 3 [MS]). The mass spectra data confirmed the mass-to-charge ratio for CBD in SGF and physiological buffer and matched the CBD standard (Fig. 4). The mass spectra data confirmed the mass-to-charge ratio for Δ8-THC and Δ9-THC formed in SGF and matched with the standards (Figs. 5 and 6). Table 4 provides a summary of the mass spectra data collected for CBD, Δ9-THC, and Δ8-THC standards and incubation samples.

FIG. 2.

UPLC–UV chromatograms in working standard (A), SGF at 75 min (B), HEPES at 360 min (C). UPLC, ultra-performance liquid chromatography; HEPES, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid.

FIG. 3.

Total ion chromatograms in working standard (A), SGF at 75 min (B), HEPES at 360 min (C).

FIG. 4.

Mass spectra of CBD in working standard (A), SGF at 75 min (B), HEPES at 360 min (C).

FIG. 5.

Mass spectra of Δ9-THC in working standard (A) and SGF at 75 min (B). *A mass spectrum of Δ9-THC in HEPES at 360 minutes is not presented as there was none detected. THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

FIG. 6.

Mass spectra of Δ8-THC in working standard (A) and SGF at 75 min (B).* A mass spectrum of Δ8-THC in HEPES at 360 minutes is not presented as there was none detected.

Table 4.

Summary of Mass Spectra Data

| Sample | CBD (m/z) | Δ8-THC (m/z) | Δ9-THC (m/z) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | 316.0 | 316.1 | 315.9 |

| 75 min SGF | 316.2 | 316.8 | 315.9 |

| 360 min HEPES buffer | 316.1 | NAa | NAa |

Δ8-THC and Δ9-THC were not detected in buffer sample.

CBD, cannabidiol; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

Additional related substances at relative retention times (RRTs) of 0.44, 1.09, and 1.26 were also identified by UV in SGF samples (Fig. 2B). Two of the three peaks (RRTs 0.44 and 1.26) were detected in the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode, confirming they are cannabinoids as the selected precursor and product ions were detected. The related substance peak at RRT 1.09 appears to be formed as a secondary product related to the RRT 0.44 product (Table 3) and is also most likely a related cannabinoid. The quantities of these related substances were calculated assuming a response factor of 1.0, equivalent to CBD, to allow mass balance to be evaluated.

Incubation

In SGF, CBD degraded ∼85% after 60 min and greater than 98% at 120 min (Table 5). The Δ9-THC:Δ8-THC ratio ranged from ∼1.25:1 to 1.5:1 over the course of the study period. CBD degradation and THC formation were very rapid (Fig. 7), and CBD consumption demonstrated first-order kinetics, with a rate constant of -0.031 min−1 (R2=0.9933). Formation of THC isomers followed biphasic kinetics in which THC levels plateaued as CBD was consumed (Fig. 7). The THC levels were also impacted by secondary degradation to other related substances (Table 5). In HEPES buffer, no degradation of CBD to THC or other cannabinoids was observed over the 6-h duration of the study.

Table 5.

Degradation of CBD to THC and Related Substances in Simulated Gastric Fluid Containing 1% Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate

| Min | CBD | Δ8-THC | Δ9-THC | Total THC | Unknown RRT 0.44 | Unknown RRT 1.09 | Unknown RRT 1.26 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 34.6 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 10 | 28.3 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 7.0 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| 15 | 23.3 | 3.7 | 5.0 | 8.7 | 4.7 | 0.0 | 0.8 |

| 20 | 19.7 | 4.7 | 6.6 | 11.2 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| 30 | 14.1 | 6.6 | 9.7 | 16.2 | 4.8 | 0.6 | 2.3 |

| 45 | 8.4 | 7.3 | 11.0 | 18.3 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 3.7 |

| 60 | 5.2 | 8.1 | 12.2 | 20.3 | 2.6 | 1.5 | 4.5 |

| 75 | 3.1 | 8.2 | 12.4 | 20.6 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 5.2 |

| 90 | 1.9 | 8.7 | 12.4 | 21.1 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 5.6 |

| 120 | 0.8 | 9.3 | 12.7 | 21.9 | 0.5 | 3.2 | 6.4 |

| 150 | 0.3 | 8.7 | 11.1 | 19.8 | 0.2 | 3.7 | 6.5 |

| 180 | 0.2 | 8.9 | 10.6 | 19.5 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 6.7 |

Values are in mg (volume corrected).

RRTs, relative retention times.

FIG. 7.

CBD degradation in SGF—kinetics plotted on normal scale (A) and with CBD only on log scale (B).

Discussion

This study demonstrated the acid-catalyzed cyclization of CBD to THC in SGF. CBD was degraded into the psychoactive cannabinoids Δ9-THC and Δ8-THC in SGF, and there was no evidence of CBD conversion to Δ8-THC or Δ9-THC in HEPES buffer. It was confirmed that the impurities were THC by favorably comparing the retention time of the sample peaks with those of the reference standards. The use of MS/MS detection in parallel with the UV detection verified the expected molecular weight of the compounds and provided direct confirmation that the peaks were THC.

The consistent CBD degradation in SGF led to a clear understanding of the kinetics of THC formation in an acidic environment, and the characterization of this rate enabled us to estimate the conversion of CBD to THC after oral dosing. Specifically, since CBD degradation demonstrated first-order kinetics, the formation of THC (and other related cannabinoids) can be conservatively estimated by using the inverse of this rate (i.e., +0.031 min−1). The quantity of THC formed after oral administration of CBD-containing medications can thus be calculated—provided that the proportion of the CBD dose that would be soluble in the acidic gastric environment and thus “available” for degradation is also known. In a true physiological environment, this proportion depends on multiple factors, including (but not limited to) partitioning out of the lipid dosage form, enzyme activity, emulsification, and fasting state. Determining actual CBD solubility in gastric fluid would require studies in human subjects. Based on our results, however, it is clear that at least some portion of an orally ingested dose of CBD will be soluble and degrade to THC.

We propose the following equation to describe THC exposure after a given time, where

|

In a patient treated with 700 mg oral CBD formulated in a lipid environment (e.g., oil-based solution), even if just 1% of the CBD dose were soluble, total cannabinoid levels, primarily Δ9-THC and Δ8-THC with other degradation products, would be 6.5 mg after 30 min and 13 mg after 60 min. Although the precise activity cannot be definitively determined until in vivo data are available, the central finding remains—significant levels of psychoactive Δ9-THC, Δ8-THC, and other related compounds are formed when CBD is taken orally. With higher CBD doses, greater solubility, and/or longer gastric residence time, it is not difficult to envision scenarios in which Δ9-THC levels of 20–30 mg or higher are reached (i.e., 1–1.5 times the maximum recommended daily dose).30

Our findings support the reproducibility of previous work.6,28,31–33 In the 1940s, before the structure of CBD had been established, Adams et al. observed that acidic conditions can convert CBD to cannabinoids that cause behavioral and physiological effects comparable to those seen with inhaled THC.31,32 In the 1960s, Gaoni and Mechoulam showed that various acidic reagents can degrade CBD and lead to the formation of Δ9-THC33 and Δ8-THC,6 the latter of which has been associated with physiological effects that are similar to, but less pronounced than, Δ9-THC (e.g., tachycardia and peak highs).34 More recent experiments have demonstrated that CBD can be converted to Δ9-THC in artificial gastric fluid, resulting in measurable pharmacological effects in murine models (e.g., catalepsy, hypothermia, sleep prolongation, and antinociception).28 This study extends these findings by showing the conversion rate of CBD to THC over 1 to 3 h, a study period that approximates the duration of exposure in oral dosing situations and may have important implications for patients being treated with orally administered CBD.

If inhaled and human-metabolized CBD do not convert to Δ9-THC, as previous research suggests,30 and the trace amounts of THC in plant-extracted CBD medications cannot account for the high incidence of somnolence and fatigue in recent studies,26,27 the events may be partially explained by the sedating effects of antiepileptic drugs.35,36 However, these effects may also be a normal response to the psychoactive Δ9-THC and Δ8-THC released from the nonpsychoactive precursor CBD in the highly acidic gut milieu. Since studies of the effects of simulated gastric juice on CBD have shown that acid degradation also yields at least two hexahydrocannabinols that have been associated with catalepsy, hypothermia, sleep prolongation, and antinociception in mice,28 additive or synergistic activity at multiple cannabinoid receptors may be involved. Orally administered formulations of CBD, once thought devoid of the psychotropic side effects of THC,5,7,23 appear to convert in the gut by acid-catalyzed cyclization to clinically relevant concentrations of psychoactive cannabinoids, primarily Δ9-THC and Δ8-THC, that may affect clinical response and lead to adverse events.

Despite persistent challenges with dosing and administration, CBD-based therapies have a good safety profile7,22 and a potential for efficacy in the treatment of a variety of medical conditions. The rapidly evolving sciences of drug delivery and cannabinoid pharmacology1 may soon lead to breakthroughs that will improve access to the benefits of this pharmacological class of agents. In addition, current technologies, such as transdermal-based therapy, may be able to eliminate the potential for psychotropic effects due to this acid-catalyzed cyclization by delivering CBD through the skin and into the neutral, nonreactive environment of the systemic circulation.

Conclusions

Gastric fluid without enzymes converts CBD into the psychoactive components Δ9-THC and Δ8-THC, which suggests that the oral route of administration may increase the potential for psychomimetic adverse effects from CBD. Confirmation of THC formation was demonstrated by comparison of mass spectral analysis, mass identification, and retention time of THC in the SGF samples against authentic reference standards. The acid-catalyzed cyclization of CBD in SGF revealed first-order kinetics of CBD degradation. This finding indicates that the acidic gastric environment during normal gastrointestinal transit may expose patients treated with oral CBD to levels of THC and other psychoactive cannabinoids that exceed the threshold for a physiological response. Delivery methods that decrease the potential for formation of psychoactive cannabinoids should be explored.

Abbreviations Used

- CBD

cannabidiol

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- HSS

high-strength silica

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring

- RRTs

relative retention times

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SGF

simulated gastric fluid

- THC

tetrahydrocannabinol

- TQD MS/MS

tandem quadrupole mass spectrometry

- UPLC

ultra-performance liquid chromatography

- USP

United States Pharmacopeia

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kiran Morishetti, PhD, for optimizing and running the UPLC/MS sample analyses. This study was supported by Zynerba Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Medical writing services were provided by Christopher Caiazza.

Author Disclosure Statement

J.M. and B.L. were paid consultants, and T.S., C.O., and S.L.B. are employees, of Zynerba Pharmaceuticals. T.Y. has no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Fine PG, Rosenfeld MJ. The endocannabinoid system, cannabinoids, and pain. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2013;4:e0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devinsky O, Cilio MR, Cross H, et al. Cannabidiol: pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia. 2014;55:791–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Alfy AT, Ivey K, Robinson K, et al. Antidepressant-like effect of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa L. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;95:434–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R. Isolation, structure and partial synthesis of an active constituent of hashish. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:1646–1647 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mechoulam R, Hanus L. Cannabidiol: an overview of some chemical and pharmacological aspects. Part I: chemical aspects. Chem Phys Lipids. 2002;121:35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R. Concerning the isomerization of D1 to D6-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:5673–5675 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pertwee RG. The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:199–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramovici H. Cannabis (marihuana, marijuana) and the cannabinoids. Available at www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/marihuana/med/infoprof-eng.php (accessed February16, 2016)

- 9.Aggarwal SK. Cannabinergic pain medicine: a concise clinical primer and survey of randomized-controlled trial results. Clin J Pain. 2013;29:162–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraft B. Is there any clinically relevant cannabinoid-induced analgesia? Pharmacology. 2012;89:237–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guindon J, Hohmann AG. The endocannabinoid system and pain. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009;8:403–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackie K. Signaling via CNS cannabinoid receptors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;286:S60–S65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maccarrone M, Gasperi V, Catani MV, et al. The endocannabinoid system and its relevance for nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 2010;30:423–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serrano A, Parsons LH. Endocannabinoid influence in drug reinforcement, dependence and addiction-related behaviors. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;132:215–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Battista N, Di Tommaso M, Bari M, et al. The endocannabinoid system: an overview. Front Behav Neurosci. 2012;6:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhornitsky S, Potvin S. Cannabidiol in humans-the quest for therapeutic targets. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2012;5:529–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robson P. Human studies of cannabinoids and medicinal cannabis. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2005;168:719–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones NA, Hill AJ, Smith I, et al. Cannabidiol displays antiepileptiform and anti-seizure properties in vitro and in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:569–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roser P, Vollenweider FX, Kawohl W. Potential antipsychotic properties of central cannabinoid (CB1) receptor antagonists. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11:208–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Booz GW. Cannabidiol as an emergent therapeutic strategy for lessening the impact of inflammation on oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1054–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rock EM, Goodwin JM, Limebeer CL, et al. Interaction between non-psychotropic cannabinoids in marihuana: effect of cannabigerol (CBG) on the anti-nausea or anti-emetic effects of cannabidiol (CBD) in rats and shrews. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;215:505–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunha JM, Carlini EA, Pereira AE, et al. Chronic administration of cannabidiol to healthy volunteers and epileptic patients. Pharmacology. 1980;21:175–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izzo AA, Borrelli F, Capasso R, et al. Non-psychotropic plant cannabinoids: new therapeutic opportunities from an ancient herb. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:515–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones NA, Glyn SE, Akiyama S, et al. Cannabidiol exerts anti-convulsant effects in animal models of temporal lobe and partial seizures. Seizure. 2012;21:344–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta S. Dr. Sanjay Gupta: It's time for a medical marijuana revolution. Available at www.cnn.com/2015/04/16/opinions/medical-marijuana-revolution-sanjay-gupta (accessed February16, 2016)

- 26.Press CA, Knupp KG, Chapman KE. Parental reporting of response to oral cannabis extracts for treatment of refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;45:49–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devinsky O, Sullivan J, Friedman D, et al. Epidiolex (cannabidiol) in treatment- resistant epilepsy. Poster presented at 67th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, April18–25, 2015, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe K, Itokawa Y, Yamaori S, et al. Conversion of cannabidiol to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and related cannabinoids in artificial gastric juice, and their pharmacological effects in mice. Forensic Toxicol. 2007;25:16–21 [Google Scholar]

- 29.United States Pharmacopeia. The dissolution procedure: development and validation. Chapter 1092. Available at www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp_pdf/EN/gc_1092.pdf (accessed February12, 2016)

- 30.Marinol® (dronabinol) capsules. Prescribing information. Unimed Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Marietta, GA, 2006. Available at www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/marinol_PI.pdf (accessed February16, 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams R, Pease DC, Cain CK, et al. Structure of cannabidiol. VI. Isomerization of cannabidiol to tetrahydrocannabinol, a physiologically active product. Conversion of cannabidiol to cannabinol. J Am Chem Soc. 1940;62:2402–2405 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams R, Cain CK, McPhee WD, et al. Structure of cannabidiol. XII. Isomerization to tetrahydrocannabinols. J Am Chem Soc. 1941;63:2209–2213 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R. The isomerization of cannabidiol to tetrahydrocannabinols. Tetrahedron. 1966;22:1481–1488 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gong H, Jr., Tashkin DP, Simmons MS, et al. Acute and subacute bronchial effects of oral cannabinoids. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;35:26–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bansal D, Azad C, Kaur M, et al. Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs in North Indian pediatric outpatients. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36:107–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson M, Egunsola O, Cherrill J, et al. A prospective study of adverse drug reactions to antiepileptic drugs in children. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

Cite this article as: Merrick J, Lane B, Sebree T, Yaksh T, O'Neill C, Banks SL (2016) Identification of psychoactive degradants of cannabidiol in simulated gastric and physiological fluid, Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 1:1, 102–112, DOI: 10.1089/can.2015.0004.