Abstract

The woodland strawberry, Fragaria vesca, holds great promise as a model organism. It not only represents the important Rosaceae family that includes economically important species such as apples, pears, peaches and roses, but it also complements the well-known model organism Arabidopsis thaliana in key areas such as perennial life cycle and the development of fleshy fruit. Analysis of wild populations of A. thaliana has shed light on several important developmental pathways controlling, for example, flowering time and plant growth, suggesting that a similar approach using F. vesca might add to our understanding on the development of rosaceous species and perennials in general. As a first step, 298 F. vesca plants were analyzed using microsatellite markers with the primary aim of analyzing population structure and distribution of genetic diversity. Of the 68 markers tested, 56 were polymorphic, with an average of 4.46 alleles per locus. Our analysis partly confirms previous classification of F. vesca subspecies in North America and suggests two groups within the subsp. bracteata. In addition, F. vesca subsp. vesca forms a single global population with evidence that the Icelandic group is a separate cluster from the main Eurasian population.

Introduction

All species of Fragaria are area-specific or continentally endemic, apart from F. chiloensis and the woodland strawberry, Fragaria vesca L. (2n = 2x = 14). F. vesca has a vast natural distribution throughout the Holarctic [1–4] (Fig 1), with the notable exception of the North Atlantic islands of Greenland [5] and the Faroe Islands, as well as Svalbard where it has so far not been found [6]. On the other hand, F. vesca is widespread in Iceland [7–9], where it can be found on south-facing hillsides up to 400 MSL [8] and has been observed in the same regions at least since the year 1771 [10]. Although Icelandic vascular plants originated primarily from Europe, some are known to have originated from the North American continent [11]. However, the origin of the Icelandic strawberry population is uncertain. A comprehensive taxonomic study of the American strawberry genus describes four subspecies of F. vesca in North America: F. vesca subsp. bracteata, F. vesca subsp. vesca, F. vesca subsp. californica, and F. vesca subsp. americana[4]. However, molecular analysis has suggested that F. vesca subsp. bracteata might be split into two groups based on plastome sequences, which correspond with geography [12]. The proposed geographical distribution of the F. vesca species and subspecies is shown in Fig 1 [4,13,14]. Hybrids between subspecies could exist in the area where their distribution overlaps, as seen in Fig 1.

Fig 1. The natural geographical distribution of Fragaria vesca in the northern hemisphere and an overview of collection sites.

Included are subspecies F. vesca subsp. bracteata (yellow shading), F. vesca subsp. vesca (brown shading), F. vesca subsp. californica (orange shading), and F. vesca subsp. americana (green shading). See supplementary S1 Table for detailed information on collection sites including coordinates. A single collection site in Bolivia is excluded from the map. Based on a map created by David Eccles, username 'Gringer', who has released this work into the public domain without any conditions. The map is available here: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Worldmap_northern.svg.

Twenty-two wild species are recognized in the Fragaria genus [2–4], including the newly discovered F. cascadensis [15]. In addition, three wild hybrids are known: F. × bifera, a hybrid of F. vesca and F. viridis found in Europe [16], F. × bringhurstii [17], and F. × ananassa subsp. cuneifolia. The Fragaria genus is one of ninety genera in the Rosaceae [18], a family that includes many economically important species such as the octoploid dessert strawberry (F. × ananassa), apple (Malus domestica), pears (Pyrus spp.), peach (Prunus persica), and roses (Rosa spp.) [18], which together make the Rosaceae one of the most economically valuable of all plant families [19].

F. vesca has repeatedly been proposed as a research model for the Rosaceae [20–22]. Arguments for this include the fact that F. vesca is a diploid perennial species with a small, fully sequenced genome (240 Mb [20] revised at 206 Mb [18]), an efficient genetic transformation method is available [23], it can be propagated either by seeds or clonally via stolons or branch crowns, and the seed-to-seed cycle is relatively short, only 12–16 weeks [24]. In addition, as a maternal ancestor of F. × ananassa [3], F. vesca shares a substantial sequence identity with this economically-important fruit crop. Although, the well-known model plant Arabidopsis thaliana does have a smaller genome and is already a favorite in plant research [25], it is usually an annual unlike F. vesca and it does not suffice for research on perennial-specific traits and development and ripening of fleshy fruit [26]. The wide geographical range of F. vesca from sub-tropic areas to the arctic and up to 3000 MSL [27] increases its potential as a model for research on adaptive traits. To understand these key traits and their regulation, it is of great importance to analyze natural variability and its selective advantage in certain environments. The value of naturally occurring genetic variation for basic research is already well demonstrated through the use of wild Arabidopsis accessions [28, 29].

The use of wild accessions for the study of environmental adaptation requires the comprehensive understanding of the biogeographic patterns of the populations of interest. Large numbers of microsatellite markers have been developed for Fragaria species [30–36], with over 4000 SSR markers developed [33] since the sequencing of the F. vesca genome [20]. These markers facilitate population genomic research in F. vesca. Furthermore, SSR markers developed in F. vesca have an observed transferability of over 90% to F. × ananassa [37], and they have been used to construct linkage maps for F. × ananassa [33,35].

Strawberries have most likely been consumed by humans for thousands of years [2], but the cultivation of the woodland strawberry is believed to date back only centuries, with the domestication process started by the discovery of a perpetual flowering plant in the low Alps east of Grenoble about 350 years ago [38]. The oldest registered cultivars ‘Rügen’ and ‘Baron Solemacher’, released in 1920 and 1935, respectively [39], are still available along with many others in seed banks and stores. Domestication can greatly affect the distribution of both plants and animals, with domestic varieties known in some cases to return to the wild after human-mediated long-distance dispersal, possibly affecting biogeographic patterns observed through molecular analyses. For research aimed at elucidating biogeography signatures it is therefore important to include samples representing available cultivars.

Reduced diversity in crop plants compared to wild relatives is well recognized in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) [40], the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) [41], and the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) [42]. This domestication reduction in diversity is not universally true. For example, apple (Malus domestica), a perennial crop plant, has not undergone any significant loss in diversity during the last 800 years [43]. Moreover, maize contains about 60–80% of the diversity of its ancestor teosinte [44, 45]. Also, einkorn wheat, one of the first domesticated crops, has not undergone any considerable diversity reduction [46], and domesticated chili peppers show only ~10% reduction in genetic diversity [47]. To effectively assess the reduction of genetic diversity associated with domestication it is necessary to have a fair estimation of the genetic diversity found in the wild relatives. To achieve this, genetic analyses of a collection of wild accessions are needed.

Due to the loss of genetic diversity in crop species, their wild relatives have long been suggested as a potentially valuable source of novel traits [48]. This has been confirmed on multiple occasions, Maxted and Kell [49] reported 291 studies describing attempts to introgress desired traits into 29 crop species from wild relatives and it has been suggested for strawberries by Liston et al. [2]. The trait of day neutrality was introgressed from F. virginiana subsp. glauca into F. × ananassa [18, 50] and old cultivars have introgression from F. moschata and F. chiloensis genomes in their pedigree [51]. However, in practice, the introgression of traits into a desired cultivar through conventional crossing can be very time consuming–nearly impossible in species of different ploidy such as in the case of F. vesca and F. × ananassa–with backcrossing and phenotyping taking years or decades in some plant species. However, methods such as marker assisted selection (MAS) or more recent genomic selection [52], and novel methods of genome editing [53], promise to significantly speed up the use of such natural diversity.

F. vesca is known to possess traits of interest for resistance to both abiotic and biotic stress [1, 4] as well as fruit aroma [54]. Novel traits from wild Fragaria species have been introgressed into cultivars in strawberry breeding programs [1, 55]. Warschefsky et al. [48] proposed that future work in using natural variation for breeding should focus on building a broad collection of wild relatives and sequencing of their genomes. To increase our understanding of the biogeography of F. vesca with the aim of furthering its use in genetic and genomic research and to shed light on the origin of the Icelandic F. vesca population we undertook a population genomic analysis of 295 F. vesca samples originating from Eurasia and America, using 56 SSR markers.

Materials and methods

A global Fragaria vesca collection

Plants or berries were collected from a total of 274 locations in 31 countries and 16 states (US) around the world (S1 Table) with the aim of creating a global collection representing the current wild distribution of F. vesca. Despite our best efforts we were not able to fully cover the current global distribution of introduced F. vesca, with samples missing from areas such as Hawaii, New Zealand, Australia, southern Africa, Madagascar, the Canary Islands, and the Cape Verde Islands, as well as several South American countries. Additionally, 26 cultivars were included in the study, giving a total number of 298 plants. In total, 232 Eurasian plants were analyzed (not including cultivars and outgroups), including 54 from Iceland, 37 accessions originating from North America, one from South America, and two from Japan. Also, two species other than F. vesca were included as outgroups: F. chinensis from China and F. viridis from Sweden (both accessions came taxonomically identified from USDA Germplasm Resources Information Network—GRIN). All sampling was done in accordance with regional laws and regulations governing the collection of plant material for research purposes. Accession numbers for material received from GRIN are listed in S1 Table. The distribution of sampling sites for all wild samples is shown in Fig 1.

DNA isolation, marker amplification and fragment detection

Genomic DNA was extracted from homogenized young leaf tissue using the DNeasy 96 Plant Kit or DNeasy Plant Mini Kit from QIAGEN® (Valencia, CA). The DNeasy 96 Plant Kit protocol was modified for use with the available equipment. a Universal 320 centrifuge (Hettich GmbH & Co.) with the maximum of 4000 RPM in a Hettich 1460 rotor. The amount of DNA extracted with the DNeasy 96 Plant Kit protocol was measured using NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific).

Samples of 300 individuals (S1 Table) were analyzed using 68 microsatellite markers (S2 Table) [33, 56–58]. All markers used here are expressed simple sequence repeats (EST-SSR) markers, which are, although reported to be less polymorphic than non-genic SSR markers, of great value for population structure analysis due to their transferability between species (due to the higher conservation of genic sequences) and the fact that they make up for the lower levels of polymorphism, compared to non-genic markers, by being concentrated in gene-rich regions [59]. The microsatellite markers were amplified using a TProfessional 384 thermocycler (www.biometra.de) with a 5 μl reaction volume containing 0.6 ng of genomic DNA in 1X PCR buffer (Bioline, London, UK), 3 mM MgCl2, 0.08U of BIOTAQ DNA polymerase (Bioline), 0.8 mM dNTPs, and 0.4 μM of each primer. A modified touchdown PCR protocol was followed, as described by Sato et al. [60]. The PCR products were separated by an ABI 3730xl fluorescent fragment analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The polymorphisms were investigated using GeneMarker software (http://softgenetics.com/).

Analysis of genetic diversity and population structure

Descriptive statistics were calculated using GenAlEx 6.501 [61, 62] for each microsatellite marker, including the number of observations (N) for each marker, number of alleles (Na) per locus, and both observed (Ho), and expected (He) heterozygosity. For a population-wide analysis GenAlEx 6.501 was used to calculate the average number of alleles per population (Nap), number of effective alleles (Ne), number of private alleles (NPA), observed (Ho) and expected (He) heterozygosity, and the fixation index (F = 1-(Ho/He)). GenAlex was also used for principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and pairwise population Fst values (FST = 1- (average He/HT)). Presence of null alleles was tested using Freena [63]. Additional statistics were calculated in PowerMarker 3.25 [64], including the polymorphic information content (PIC) and the major allele frequencies (MAF) for each marker. PowerMarker was also used to construct an evolutionary distance matrix based on Nei et al.’s DA distance method [65]. A phylogenetic tree of a split network based on this matrix was drawn up using SplitsTree 4 [66]. Mega version 5 [67] was used to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining method [68] with bootstrap values.

To identify the number of populations and admixtures, the dataset was analyzed using the admixture model of Structure 2.3.4 [69–72] and the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method for estimation of probabilities. All loci were assumed to be independent and in linkage equilibrium. Populations were not pre-described. All Structure runs were repeated 5 times for each K from 1–20 for the whole dataset and for each K from 1–10 for the ‘American’ and ‘Eurasian’ data-sets. The MCMC method was run with a burn-in period of 50,000 and 10,000 repetitions. Other settings were by default. Structure Harvester [73] was used to find the optimal number of clusters (K) for each dataset, where the average likelihood values K (L(K)) for each run were used to find ΔK, i.e., the rate of change in lnPr(X|K), since the maximum value of L(K) can give an overestimate of clusters [74].

Results

Descriptive statistics of microsatellite markers

Of the 68 markers amplified, 10 were monomorphic and therefore uninformative. In addition, more than two alleles were repeatedly observed per sample for markers FVES2533 and FVES0634. As this is not consistent with the diploid nature of F. vesca, these markers were excluded from further analysis. Descriptive statistics for each of the remaining 56 markers used are listed in Table 1. The mean number of observed individuals per marker (N) was 289.9. The 56 polymorphic markers had numbers of alleles ranging from 2–16 for all samples, with a total of thirteen bi-allelic markers. A total of 250 alleles was observed for the 56 markers, giving a mean number of 4.46 alleles per locus. The observed heterozygosity (Ho) ranged from zero for thirteen markers to 0.938 for marker FVES3440 with a mean Ho of 0.075. The expected heterozygosity (He) ranged from 0.003 for marker FAES0293 to 0.797 for marker FVES0109, with a mean of 0.170. The polymorphic information content (PIC) ranged from 0.003 for marker FAES0293 to 0.78 for marker FVES0109, with a mean of 0.151. The major allele frequency (MAF) ranged from 0.393 for marker FVES0109 to 0.998 for marker FAES0293, with an average of 0.885.

Table 1. Summary statistics of markers tested.

| Marker | N | Na | Ho | He | PIC | Nulla | MAF | Marker | N | Na | Ho | He | PIC | Nulla | MAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAES0093 | 295 | 4 | 0.034 | 0.085 | 0.084 | 0.60 | 0.956 | FVES1201 | 294 | 3 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.50 | 0.997 |

| FAES0208 | 294 | 4 | 0.010 | 0.069 | 0.068 | 0.85 | 0.964 | FVES1213 | 294 | 7 | 0.065 | 0.455 | 0.410 | 0.86 | 0.707 |

| FAES0293 | 295 | 2 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.00 | 0.998 | FVES1230 | 295 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 1.00 | 0.997 |

| FAES0357 | 291 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.163 | 0.149 | 1.00 | 0.911 | FVES1313 | 289 | 5 | 0.017 | 0.406 | 0.372 | 0.96 | 0.751 |

| FAES0376 | 294 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 1.00 | 0.997 | FVES1356 | 295 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 1.00 | 0.997 |

| FAES0465 | 288 | 5 | 0.000 | 0.028 | 0.027 | 1.00 | 0.986 | FVES1362G | 295 | 4 | 0.000 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 1.00 | 0.990 |

| FAES0479 | 276 | 2 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.00 | 0.995 | FVES1392 | 294 | 2 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.013 | -0.01 | 0.993 |

| FP0380 | 292 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 1.00 | 0.997 | FVES1470 | 281 | 4 | 0.007 | 0.042 | 0.041 | 0.83 | 0.979 |

| FP0488 | 260 | 8 | 0.019 | 0.122 | 0.119 | 0.84 | 0.937 | FVES1621 | 295 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 1.00 | 0.997 |

| FVES0109 | 291 | 16 | 0.206 | 0.797 | 0.780 | 0.74 | 0.393 | FVES1640 | 295 | 5 | 0.051 | 0.297 | 0.257 | 0.83 | 0.820 |

| FVES0128 | 294 | 9 | 0.109 | 0.504 | 0.422 | 0.78 | 0.624 | FVES1711 | 295 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 1.00 | 0.997 |

| FVES0233 | 293 | 5 | 0.020 | 0.207 | 0.188 | 0.90 | 0.884 | FVES1724 | 293 | 7 | 0.089 | 0.361 | 0.314 | 0.75 | 0.775 |

| FVES0381 | 285 | 7 | 0.032 | 0.095 | 0.093 | 0.67 | 0.951 | FVES1793 | 294 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 1.00 | 0.997 |

| FVES0392 | 295 | 4 | 0.075 | 0.423 | 0.348 | 0.82 | 0.708 | FVES1816 | 295 | 3 | 0.125 | 0.124 | 0.119 | -0.01 | 0.934 |

| FVES0435 | 295 | 6 | 0.088 | 0.404 | 0.338 | 0.78 | 0.731 | FVES1877 | 295 | 4 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.33 | 0.995 |

| FVES0459 | 293 | 7 | 0.010 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.83 | 0.969 | FVES1907 | 295 | 3 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.67 | 0.995 |

| FVES0463 | 293 | 3 | 0.024 | 0.101 | 0.098 | 0.76 | 0.947 | FVES2235 | 288 | 3 | 0.049 | 0.285 | 0.246 | 0.83 | 0.828 |

| FVES0480 | 235 | 8 | 0.302 | 0.391 | 0.361 | 0.23 | 0.764 | FVES2316 | 295 | 3 | 0.003 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.80 | 0.992 |

| FVES0513 | 294 | 3 | 0.003 | 0.037 | 0.036 | 0.91 | 0.981 | FVES2349 | 294 | 4 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.66 | 0.990 |

| FVES0567 | 294 | 5 | 0.010 | 0.047 | 0.046 | 0.78 | 0.976 | FVES2369 | 295 | 6 | 0.037 | 0.206 | 0.190 | 0.82 | 0.885 |

| FVES0577 | 295 | 3 | 0.000 | 0.378 | 0.309 | 1.00 | 0.749 | FVES2661 | 294 | 5 | 0.017 | 0.027 | 0.027 | 0.37 | 0.986 |

| FVES0794 | 294 | 5 | 0.085 | 0.562 | 0.465 | 0.85 | 0.485 | FVES2882 | 295 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 1.00 | 0.997 |

| FVES0960 | 294 | 6 | 0.007 | 0.180 | 0.157 | 0.96 | 0.912 | FVES2901 | 293 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 1.00 | 0.997 |

| FVES0989 | 295 | 4 | 0.017 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.54 | 0.981 | FVES3274 | 292 | 5 | 0.007 | 0.073 | 0.072 | 0.91 | 0.962 |

| FVES1031 | 294 | 6 | 0.003 | 0.034 | 0.034 | 0.90 | 0.983 | FVES3330 | 295 | 2 | 0.112 | 0.106 | 0.100 | -0.06 | 0.944 |

| FVES1070 | 294 | 4 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.86 | 0.988 | FVES3346 | 271 | 5 | 0.697 | 0.491 | 0.397 | -0.42 | 0.622 |

| FVES1156 | 295 | 4 | 0.017 | 0.088 | 0.086 | 0.81 | 0.954 | FVES3440 | 288 | 3 | 0.938 | 0.504 | 0.382 | -0.86 | 0.517 |

| FVES1160 | 242 | 7 | 0.446 | 0.478 | 0.418 | 0.07 | 0.676 | FVES3693 | 288 | 10 | 0.417 | 0.662 | 0.625 | 0.37 | 0.523 |

| Average | 289.9 | 4.46 | 0.075 | 0.170 | 0.151 | 0.11 | 0.885 |

N, number of individuals analyzed for each marker; Na, average number of alleles for each marker; Ho, observed heterozygosity; He, expected heterozygosity; PIC, polymorphism information content; Nulla, presence of null alleles; MAF, major allele frequency.

Of the 298 accessions in the collection, three samples, one F. vesca subsp. americana (ID 28) and two Eurasian F. vesca subsp. vesca (ID numbers 145 and 146), were excluded from the analysis due to a higher than expected number of alleles per marker. In these samples, the average number of alleles per locus was 2.4, 2.4 and 2.5, respectively, indicating that they might be polyploids or the results of mixed samples. In addition two Icelandic samples were omitted from analysis due to a labelling mistake.

Population structure and genetic diversity

Descriptive statistics for each proposed population are listed in Table 2. The highest mean number of alleles, 1.98, was found in the Eurasian group (excluding Iceland) and the lowest in the Japanese samples 1.08. F. vesca subsp. vesca showed the highest values for Ne = 1.26, Ho = 0.11 and He = 0.15. The highest frequency of private alleles, NPA = 0.30, was found in the F. vesca subsp. bracteata ‘Rocky Mts’ group, with the ‘Pacific Coast’ group tied at 0.26 with the Eurasian group.

Table 2. Results of microsatellite analysis by populations.

| N | Nap | Ne | NPA | Ho | He | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. vesca subsp. americana | 5 | 1.29±0.07 | 1.18±0.06 | 0.11±0.04 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.10±0.02 | 0.41±0.08 |

| F. vesca subsp. bracteata ‘Rocky Mts’ | 7 | 1.76±0.12 | 1.39±0.07 | 0.30±0.08 | 0.09±0.02 | 0.19±0.03 | 0.49±0.06 |

| F. vesca subsp. bracteata ‘Pacific Coast’ | 13 | 1.53±0.11 | 1.22±0.05 | 0.26±0.07 | 0.09±0.02 | 0.12±0.02 | 0.26±0.06 |

| F. vesca subsp. californica | 4 | 1.20±0.06 | 1.15±0.05 | 0.03±0.02 | 0.08±0.03 | 0.09±0.02 | 0.05±0.10 |

| Cultivars | 26 | 1.48±0.12 | 1.14±0.04 | 0.03±0.02 | 0.04±0.02 | 0.08±0.02 | 0.59±0.07 |

| Eurasian F. vesca subsp. vesca | 176 | 1.98±0.21 | 1.23±0.07 | 0.26±0.08 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.11±0.02 | 0.42±0.06 |

| Icelandic F. vesca subsp. vesca | 52 | 1.52±0.11 | 1.14±0.05 | 0.06±0.03 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.07±0.02 | 0.41±0.08 |

| Japanese F. vesca subsp. vesca | 2 | 1.08±0.04 | 1.08±0.04 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.05±0.03 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.00±0.13 |

| American F. vesca subsp. vesca | 8 | 1.62 ±0.12 | 1.26±0.05 | 0.02±0.02 | 0.11±0.03 | 0.15±0.02 | 0.22±0.07 |

| Total | 1.41±0.03 | 1.16±0.02 | 0.09±0.01 | 0.10±0.01 | 0.23±0.03 |

N, number of individuals in each population; Na, average number of alleles over all markers; Ne, number of effective alleles; NPA, number of private alleles unique to a single population; Ho, observed heterozygosity; He, expected heterozygosity; F, fixation index. Standard error (±SE) is shown for all averages.

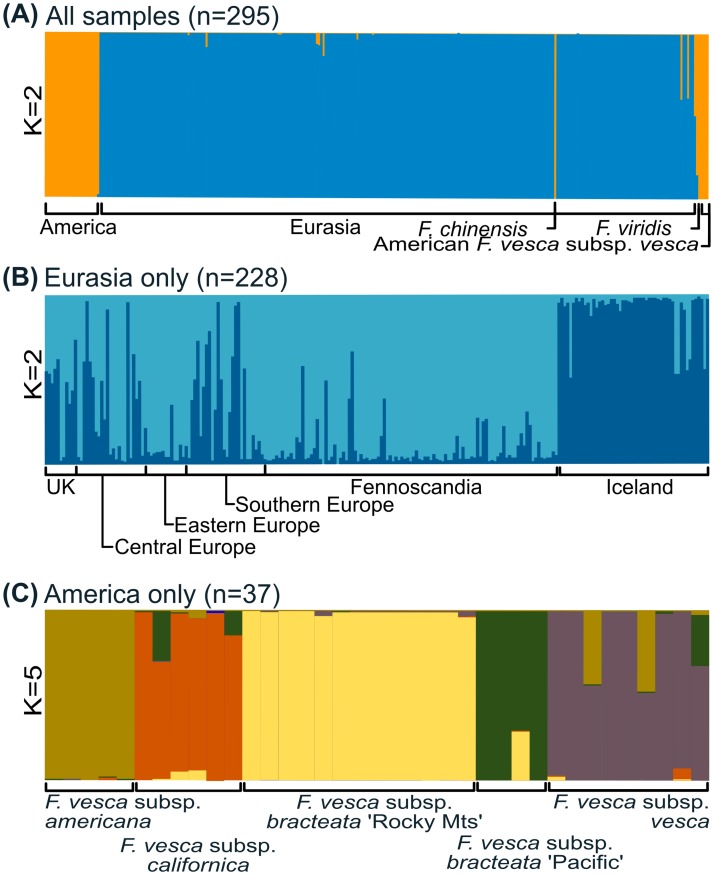

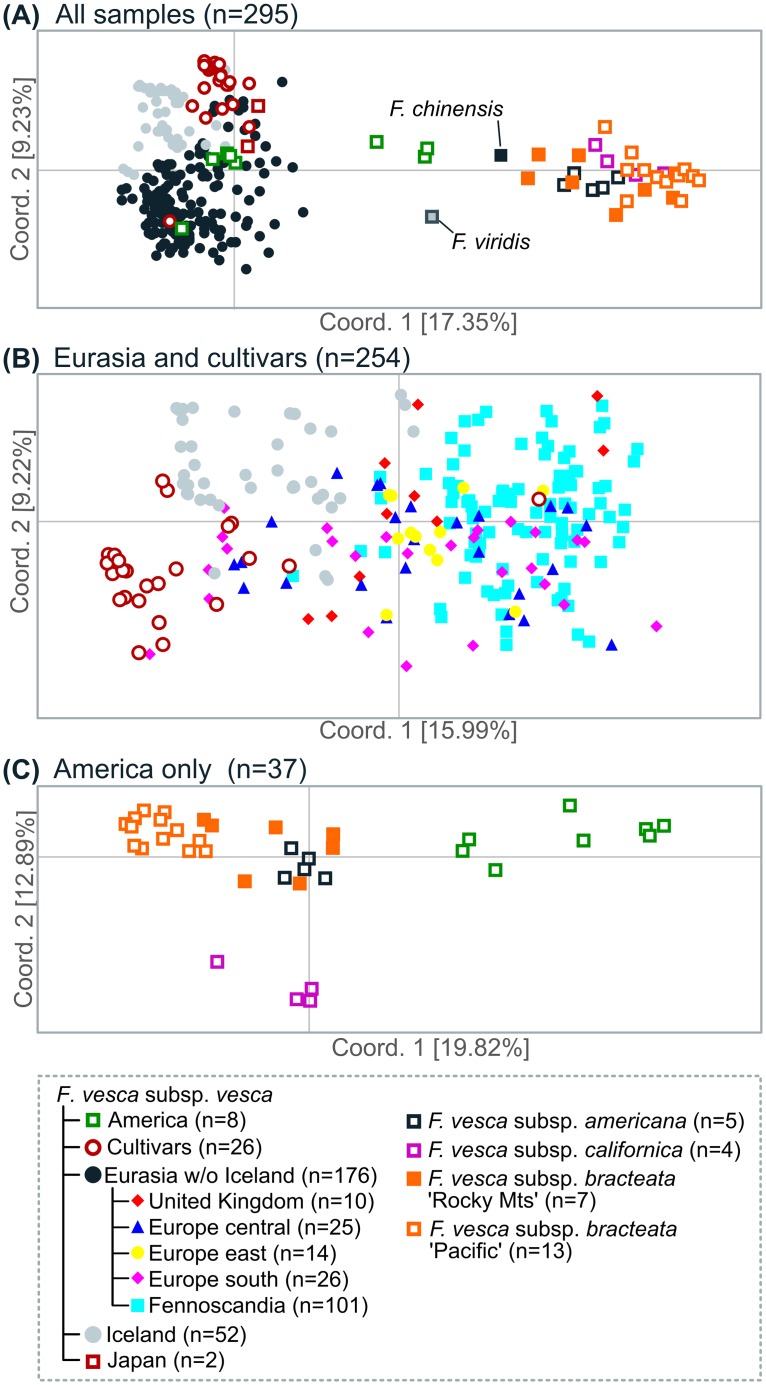

The Structure admixture results for the whole dataset, including all wild individuals and cultivars (n = 295), suggest that the collection should be split into two sub-populations, with K = 2 (ΔK = 127.56) (S1 Fig and Fig 2A). This analysis groups cultivars with the Eurasian samples, while clearly separating the Eurasian and American samples. This is somewhat corroborated by the PCoA of all individuals, which shows a strong separation of the Eurasian and the American samples (Fig 3A), while the American F. vesca subsp. vesca samples are either mixed with the Eurasian samples or end up between the two groups (Fig 3A). Another PCoA shows the cultivars overlapping with the central European samples (Fig 3B). Structure analysis with all Eurasian samples including cultivars resulted in two clusters (K = 2), one containing all wild samples and the other containing all cultivars, which is in line with the results of the PCoA (Fig 3A). To further test for divergence within the Eurasian group, the analysis was performed without the cultivars. This analysis on 228 Eurasian samples suggested the presence of two clusters (K = 2; ΔK = 28.13) (S1 Fig and Fig 2B), separating the Icelandic samples from the rest. Again, the PCoA for the Eurasian samples (Fig 3B), which explains a total of 25.21% of the variability on the first two axes, gives support to the Structure results, showing that the Icelandic samples separate from the other Eurasian samples and are most divergent from the Fennoscandian group, with some overlap with the cultivars and samples originating mostly from central Europe and the UK, as can be seen on a phylogenetic tree between all individuals (S2 Fig).

Fig 2. Results of Structure analyses.

(A) Analysis of the whole data set including cultivars. (B) Eurasian samples without the cultivars. (C) American samples only. The labels show the origin of samples based on populations proposed by (Hilmarsson, 2015).

Fig 3. Principal coordinate analysis of F. vesca microsatellite data.

(A) Analysis of the whole data set, including cultivars. (B) Eurasian samples with cultivars. (C) American samples only. The clusters suggested based on the Structure analysis are color coded.

Structure analysis of the American samples (n = 37) suggests that five clusters (K = 5) is the appropriate number (ΔK = 16.61) (S2 Fig) for the wild American samples (Fig 2C), with three clusters consisting of previously identified subspecies and F. vesca subsp. bracteata split into two clusters referred to here as ‘Pacific Coast’ and ‘Rocky Mts’ groups based on their geographical origin (Fig 2C). The PCoA analysis for the American samples (Fig 3C) explained a total of 32.71% of the variability on the first two axes and does lend some support to the Structure results.

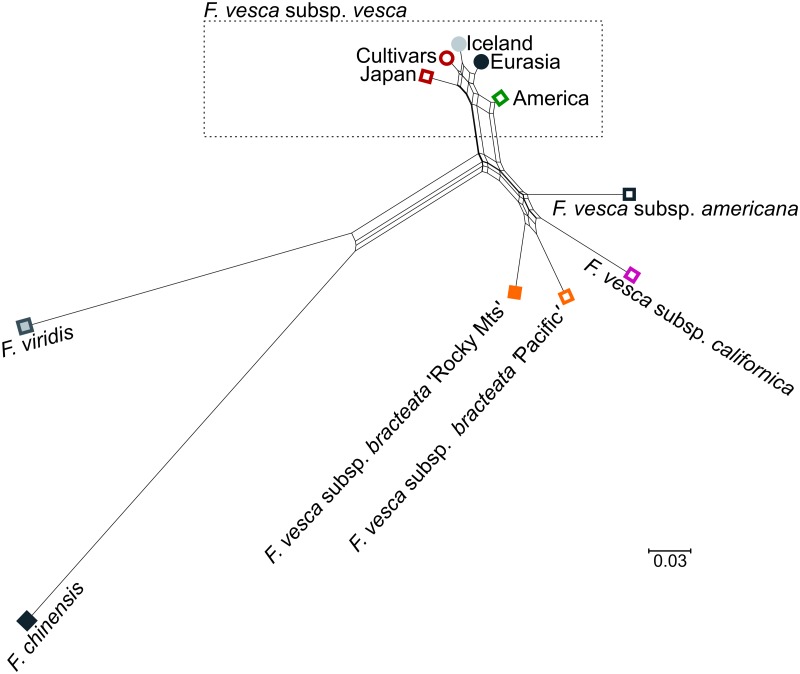

Nei et al.’s [65] DA distance was calculated for the groups presented here (S3 Table) and the results presented in a network diagram (Fig 4). The results show a clear separation between much of the American and the Eurasian samples, except for the American F. vesca subsp. vesca samples which group close to the Eurasian samples.

Fig 4. A SplitsTree analysis based on genetic distance between groups.

Groups are color coded as in Fig 3.

Discussion

In the study presented here a total of 68 EST-SSR markers, of which were 56 polymorphic, were used to analyze a global collection of 295 F. vesca samples from 274 locations in 31 countries and 16 states (US). The diversity observed for each of the markers was relatively low, with a mean number of alleles of only 4.5. These values were much lower than seen in some recent studies on Rosaceae species such as the mean number of alleles of 18.7 observed in the almond (Prunus dulcis (Mill.)) [75] and 10.8 in F. × ananassa [51], yet similar to other results observed in F. vesca, where 4.9 was the mean number of alleles from 21 microsatellites in fifteen F. vesca samples [32]. The question arises whether this reflects a poor choice of microsatellites or whether this rather reflects low levels of genetic diversity in the populations under study. The relative uniformity of alleles for each of the markers analyzed and the results of Hadonou et al. [32] might suggest that the values seen here reflect low levels of genetic diversity in the species, but it can be pointed out that although the average number of alleles was low, the most polymorphic marker revealed 16 alleles. The mean frequencies of null alleles for all the markers was 0.11. This could have been due to DNA quality leading to genotyping error, which would also explain the nine markers that revealed two alleles but high major allele frequencies. The selfing nature of F. vesca could also lead to an overestimate of null allele frequencies.

The mean observed heterozygosity (Ho) found here was 0.075 for the whole collection, considerably lower than the average expected heterozygosity (He) of 0.170. These values are then much lower than values seen, for example, in Prunus sibirica, a highly outcrossing species, with values of Ho = 0.639 and He = 0.774 [76]. One likely explanation for the discrepancy seen between Ho and He might be the existence of subpopulations within the global collection, that is the North American subspecies, confirmed here through various means, such as Structure analyses. When values for Ho and He were compared for individual subpopulations suggested here the observed heterozygosity was always lower than the expected heterozygosity, except for the Japanese samples where they were equal (Table 2). The large difference within the F. vesca subsp. bracteata ‘Rocky Mts’ group (Ho = 0.09, He = 0.19) is surprising considering the gynodioecy within the group [12]. F. vesca is a self-compatible species and low levels of observed heterozygosity have previously been reported [32, 77]. Low levels of heterozygosity could indicate low cross-fertilization and high selfing rates, but might also be explained by the asexual dispersal by means of stolons [12] or a Wahlund effect, as observed in the Siberian apricot [76]. The low He seen here, especially in some groups, e.g. the Icelandic samples, could be the result of a recent bottleneck since expansion leads to a reduced diversity [78] (Table 2). The cultivar group exhibited low diversity with the highest fixation index of all groups F = 0.59 (Table 2). The PCoA showed the tight cluster of the individuals analyzed and its divergence from the wild samples (S2 Fig). The Icelandic samples analyzed here were most closely related to the cultivars (S3 Table and visualized in Figs 3B and 4 and S2 Fig), but overlapped also with central and southern European samples.

The principal coordinate analyses performed here revealed a great difference between the Eurasian (without Iceland) and American (without American F. vesca subsp. vesca) groups (Fig 3) with genetic distances from 0.170–0.204 and Fst values from 0.194–0.354 (S3 Table). In addition, the Structure analysis placed American and Eurasian samples into separate clusters and a detailed analysis of American samples showed five clusters which consisted of the four subspecies identified by Staudt [4] (Fig 2). The morphological diagnosis by Staudt did not fully reveal this large difference between the endemic American subspecies and the subsp. vesca. However, these results could complement the results of Njuguna [12] where subsp. bracteata did split into two groups divided by the Great Basin in the western US, much as presented here, possibly because of genetic variation in loci determining sexual phenotypes [79], but differences in cytoplasmic haplotypes have been reported, with western populations dominated by one chlorotype and populations from the Rocky Mts by another [12, 79]. No evidence of hybrids between the subsp. bracteata and subsp. americana was revealed in the admixture analyses as suggested by Staudt [4] and reported by Stanley et al. [79], but this is most likely best explained by the limited sampling of the two subspecies in the current study. However, there seem to be two hybrids between subsp. americana and subsp. vesca and one between subsp. bracteata and subsp. vesca, as seen in both the admixture analyses (Fig 2C) and the PCoA analyses (Fig 3A and 3C), and in all three clusters with subsp. vesca. Hybrids between subsp. americana and subsp. vesca can be natural since their area of distribution in the northeastern United States overlap, but natural populations of subsp. bracteata are not known in this region (Fig 1), although they could have been introduced as suggested by Stanley [79]. The samples that were collected in America that group together with the European samples are categorized as Fragaria vesca subsp. vesca (Fig 1). These samples were collected in the northeastern United States, where cultivars were already being grown at the beginning of the last century [38] and therefore most likely introduced. The same conclusion can be made for the Japanese samples, as already suggested by Hultén [13], and the single Bolivian sample included in the study. The American samples all came from the GRIN germplasm and they could represent greater levels of diversity on average than observed in nature; since what gets collected and curated might be skewed in favor of phenotypically unusual individuals, leading to greater genetic diversity, as noted by Chambers et al. [80]. The number of individuals and markers affect the detection of clusters in Structure [74]. Some of the sample groups analyzed here were very small; for example, the outgroups only contained single representatives of proposed populations, samples from Japan and the F. vesca subsp. californica contained only two and four samples, respectively. It should also be mentioned that because the Evanno method calculates the mean difference between the successive likelihood values of K, there is no ΔK value for K = 1.

It is also important to mention that to maximize the accuracy of genetic distance calculations, the number of samples need to be 100 or more, although this also depends on the polymorphism of the markers used [81]. In many cases the sample collection analyzed here did not fulfill this requirement, and further studies, with larger samples and more markers or even whole genome sequencing, are therefore recommended.

It has been demonstrated that the admixture model implemented by Structure can detect the most likely number of clusters even if the samples contain low genetic variation [71]. In the Eurasian samples, where genetic variation was low, Structure revealed two clusters, suggesting two genetic populations among the genotypes collected in Eurasia (Fig 2B), with the grouping of the Eurasian samples consistent in all analytical methods used (Figs 2, 3 and 4). Despite this it is important to note that in the PCoA of individual samples there was a clear overlap between the two clusters, the Icelandic samples and those from the rest of Eurasia. Based on our results, the origin of the Icelandic strawberry population was clearly Eurasian and not American, but interestingly our analysis did not group the Icelandic samples with the Fennoscandian samples but rather showed more genetic similarity with cultivars and central European samples. This close relationship is also seen in the overlap of the two groups in the PCoA (Fig 3B). A phylogenetic tree of individuals branches the Icelandic group off from the rest of the Eurasian samples and shares a branch with most of the cultivars and some central and southern European samples (S2 Fig). One possible explanation for these results might be that the Icelandic strawberries represent a population descended from the same stock that gave rise to the modern F. vesca cultivars. However, they cannot have been recently introduced since they have been growing in the same locations for at least 250 years [10]. The possible presence of F. viridis (as F. collina) in Iceland has been reported [82] but has not been conclusively demonstrated and we found no evidence of F. viridis or of F. × bifera in this study.

The use of populations of crop wild relatives as research models has been suggested as an approach to disseminating genetic pathways of importance to adaptation [29]. For such an approach, a collection of wild material is of great importance, and bearing that in mind, we gathered a global collection of F. vesca plants and compared them with cultivars of the same species. Through our initial analysis of biogeography and genetic diversity within this worldwide collection we have confirmed the previous classification of F. vesca into subspecies using molecular markers, and we have shown that the cultivars chosen are homogeneous and group together with the Eurasian samples. Our data also divide European subsp. vesca into two groups, one consisting of an Icelandic group and some accessions from southern and central Europe, and another consisting of the rest of the Europe, although not without overlap between groups. The clear divergence between the Icelandic group and the Fennoscandian does not correlate with results for other floral species in Iceland which are related to Nordic groups [11]. We find no evidence for any population sub-structuring within the Icelandic population despite sourcing material from around the country. Further studies with more markers and possibly with a larger number of samples or samples focusing on certain geographical areas are needed to define more detailed biogeographical patterns of F. vesca.

Supporting information

(A) Whole data set, including cultivars. (B) Eurasian samples without cultivars. (C) American samples only.

(TIF)

The tree is rooted to the two other species used in the study, F. chinensis and F. viridis. Information about bootstrap values above 50 that are not at the end of branches.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

Including marker name, sequence of forward and reverse primers, GenBank accession number (Acc. no.), pattern of repeats (Repeat), chromosome location (Chr.), the linkage position (Linkage), and species name.

(DOCX)

Nei’s genetic distance (below diagonal line) and pairwise population Fst values (above diagonal line) between groups.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Snæbjörn Pálsson for constructive comments in the early stages of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The microsatellite data has been deposited to the Dryad Repository at http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.t9d41. The full citation for the data package is “Hilmarsson H, Hytönen T, Isobe S, Toivainen T, Hallsson J. Data from: Molecular analysis of a global collection of Fragaria vesca using microsatellite markers confirms previous classification of North-American subspecies and shows great divergence between American and Eurasian groups."

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Hancock JF. Strawberries. Cabi Pub; 1999. 264 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liston A, Cronn R, Ashman T-L. Fragaria: A genus with deep historical roots and ripe for evolutionary and ecological insights. Am J Bot [Internet]. 2014. October 1 [cited 2014 Sep 23]; http://www.amjbot.org/content/early/2014/09/16/ajb.1400140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rousseau-Gueutin M, Gaston A, Aïnouche A, Aïnouche ML, Olbricht K, Staudt G, et al. Tracking the evolutionary history of polyploidy in Fragaria L. (strawberry): New insights from phylogenetic analyses of low-copy nuclear genes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2009; 51(3):515–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staudt G. Systematics and Geographic Distribution of the American Strawberry Species: Taxonomic Studies in the Genus Fragaria (Rosaceae:Potentilleae). Vol. 81 London: University of California Press; 1999. 180 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Böcher T, Fedskild B, Holmen K, Jakobsen K. Grønlands Flora. 2nd ed København: P. Hasse & Søns Forlag; 1966. 307 pp. (In Danish). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blamey M, Grey-Wilson C. Myndskreytt flóra Íslands og norður-Evrópu. Skjaldborg; 1992. (In Icelandic).

- 7.Bjarnason ÁH. Íslensk flóra með litmyndum. Reykjavík: Iðunn; 1983. (In Icelandic). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristinsson H. Íslenska plöntuhandbókin Blómplöntur og byrkningar. 3rd ed Reykjavík: Mál og Menning; 2010. (In Icelandic). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Löve Á. Íslenzk ferðaflóra. Reykjavík: Almenna Bókafélagið; 1970. (In Icelandic). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ólafsson E. Ferðabók Eggerts Ólafssonar og Bjarna Pálssonar um ferðir þeirra á Íslandi árin 1752–1757. Bókaútgáfan: Örn og Örlygur hf; 1981. (In Icelandic). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eidesen PB, Ehrich D, Bakkestuen V, Alsos IG, Gilg O, Taberlet P, et al. Genetic roadmap of the Arctic: plant dispersal highways, traffic barriers and capitals of diversity. New Phytol. 2013. November 1;200(3):898–910. doi: 10.1111/nph.12412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Njuguna W, Liston A, Cronn R, Ashman T-L, Bassil N. Insights into phylogeny, sex function and age of Fragaria based on whole chloroplast genome sequencing. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013. January;66(1):17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hultén E. Atlas över växternas utbredning i Norden [Internet]. 2nd ed Stockholm: Generalsstabens litografiska anstalts förlag; 1971. (In Swedish). http://linnaeus.nrm.se/flora/di/rosa/fraga/fragvesv.jpg [Google Scholar]

- 14.USDA. Plants Profile for Fragaria vesca (woodland strawberry) [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2015 Apr 17]. http://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=FRVE

- 15.Durham S. New Strawberry Species Found in Oregon. Agric Res. 2013. July;61(6):13. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staudt G, Dimeglio LM, Davis TM, Gerstberger P. Fragaria bifera Duch.: Origin and taxonomy. Bot Jahrb. 2003;125(1):53–72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bringhurst RS, Senanayake YDA. The evolutionary significance of natural Fragaria Chiloensis X F. Vesca hybrids resulting from unreduced gametes. Am J Bot. 1966;53(10):1000–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Longhi S, Giongo L, Buti M, Surbanovski N, Viola R, Velasco R, et al. Molecular genetics and genomics of the Rosoideae: State of the art and future perspectives. Hortic Res. 2014. January 22;1:1 doi: 10.1038/hortres.2014.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dirlewanger E, Cosson P, Tavaud M, Aranzana J, Poizat C, Zanetto A, et al. Development of microsatellite markers in peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] and their use in genetic diversity analysis in peach and sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.). TAG Theor Appl Genet Theor Angew Genet. 2002. July;105(1):127–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shulaev V, Sargent DJ, Crowhurst RN, Mockler TC, Folkerts O, Delcher AL, et al. The genome of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Nat Genet. 2010. December 26;43(2):109–16. doi: 10.1038/ng.740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weebadde CK, Wang D, Finn CE, Lewers KS, Luby JJ, Bushakra J, et al. Using a linkage mapping approach to identify QTL for day-neutrality in the octoploid strawberry. Plant Breed. 2008;127(1):94–101. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slovin JP, Rabinowicz PD. Fragaria vesca, a Useful Tool for Rosaceae Genomics. In Ventura CA: American Society for Horticultural Science; 2007. [cited 2017 Feb 16]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292736043_Fragaria_vesca_a_Useful_Tool_for_Rosaceae_Genomics [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oosumi T, Gruszewski HA, Blischak LA, Baxter AJ, Wadl PA, Shuman JL, et al. High-efficiency transformation of the diploid strawberry (Fragaria vesca) for functional genomics. Planta. 2006. May;223(6):1219–30. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0170-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folta KM. Functionalizing the strawberry genome—A review. Int J Fruit Sci. 2013. January 1;13(1–2):162–74. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meinke DW, Cherry JM, Dean C, Rounsley SD, Koornneef M. Arabidopsis thaliana: A model plant for genome analysis. Science. 1998. October 23;282(5389):662, 679–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shulaev V, Korban SS, Sosinski B, Abbott AG, Aldwinckle HS, Folta KM, et al. Multiple models for Rosaceae genomics. Plant Physiol. 2008. July;147(3):985–1003. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.115618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohloff J, Kopka J, Erban A, Winge P, Wilson RC, Bones AM, et al. Metabolite profiling reveals novel multi-level cold responses in the diploid model Fragaria vesca (woodland strawberry). Phytochemistry. 2012. May;77:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koornneef M, Alonso-Blanco C, Vreugdenhil D. Naturally occurring genetic variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:141–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weigel D. Natural variation in Arabidopsis: From molecular genetics to ecological genomics. Plant Physiol. 2012. January 1;158(1):2–22. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.189845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunings AM, Moyer C, Peres N, Folta KM. Implementation of simple sequence repeat markers to genotype Florida strawberry varieties. Euphytica. 2010. May 1;173(1):63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Govan CL, Simpson DW, Johnson AW, Tobutt KR, Sargent DJ. A reliable multiplexed microsatellite set for genotyping Fragaria and its use in a survey of 60 F. × ananassa cultivars. Mol Breed. 2008. November 1;22(4):649–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadonou AM, Sargent DJ, Wilson F, James CM, Simpson DW. Development of microsatellite markers in Fragaria, their use in genetic diversity analysis, and their potential for genetic linkage mapping. Genome Natl Res Counc Can Génome Cons Natl Rech Can. 2004. June;47(3):429–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isobe SN, Hirakawa H, Sato S, Maeda F, Ishikawa M, Mori T, et al. Construction of an integrated high density simple sequence repeat linkage map in cultivated strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa) and its applicability. DNA Res Int J Rapid Publ Rep Genes Genomes. 2013. February;20(1):79–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewers KS, Styan SMN, Hokanson SC, Bassil NV. Strawberry GenBank-derived and genomic simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers and their utility with strawberry, blackberry, and red and black raspberry. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2005. January 1;130(1):102–15. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sargent DJ, Passey T, Surbanovski N, Lopez Girona E, Kuchta P, Davik J, et al. A microsatellite linkage map for the cultivated strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) suggests extensive regions of homozygosity in the genome that may have resulted from breeding and selection. TAG Theor Appl Genet Theor Angew Genet. 2012. May;124(7):1229–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sargent DJ, Hadonou AM, Simpson DW. Development and characterization of polymorphic microsatellite markers from Fragaria viridis, a wild diploid strawberry. Mol Ecol Notes. 2003;3(4):550–552. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis TM, DiMeglio LM, Yang R, Styan SMN, Lewers KS. Assessment of SSR marker transfer from the cultivated strawberry to diploid strawberry species: Functionality, linkage group assignment, and use in diversity analysis. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2006. July 1;131(4):506–12. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darrow GM. The Strawberry; History, Breeding, and Physiology. 1st ed Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1966. 447 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wachsmuth B. Annotated List of Alpine, Wild, and Musk Strawberry Varieties Currently in Cultivation [Internet]. ipke.de. 2014 [cited 2015 Jan 7]. http://www.ipke.de/atBrigitte/brigitte/list.htm

- 40.Iqbal MJ, Reddy OUK, El-Zik KM, Pepper AE. A genetic bottleneck in the “evolution under domestication”of upland cotton Gossypium hirsutum L. examined using DNA fingerprinting. TAG Theor Appl Genet Theor Angew Genet. 2001. September 1;103(4):547–54. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ortiz R, Huaman Z. Allozyme polymorphisms in tetraploid potato gene pools and the effect on human selection. TAG Theor Appl Genet Theor Angew Genet. 2001. October 1;103(5):792–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papa R, Gepts P. Asymmetry of gene flow and differential geographical structure of molecular diversity in wild and domesticated common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) from Mesoamerica. TAG Theor Appl Genet Theor Angew Genet. 2003. January;106(2):239–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gross BL, Henk AD, Richards CM, Fazio G, Volk GM. Genetic diversity in Malus ×domestica (Rosaceae) through time in response to domestication. Am J Bot. 2014. October 1;101(10):1770–9. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1400297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tenaillon MI, U’Ren J, Tenaillon O, Gaut BS. Selection versus demography: A multilocus investigation of the domestication process in maize. Mol Biol Evol. 2004. July;21(7):1214–25. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wright SI, Bi IV, Schroeder SG, Yamasaki M, Doebley JF, McMullen MD, et al. The effects of artificial selection on the maize genome. Science. 2005. May 27;308(5726):1310–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1107891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kilian B, Ozkan H, Walther A, Kohl J, Dagan T, Salamini F, et al. Molecular diversity at 18 loci in 321 wild and 92 domesticate lines reveal no reduction of nucleotide diversity during Triticum monococcum (Einkorn) domestication: Implications for the origin of agriculture. Mol Biol Evol. 2007. December;24(12):2657–68. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aguilar-Meléndez A, Morrell PL, Roose ML, Kim S-C. Genetic diversity and structure in semiwild and domesticated chiles (Capsicum annuum; Solanaceae) from Mexico. Am J Bot. 2009. June;96(6):1190–202. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warschefsky E, Penmetsa RV, Cook DR, von Wettberg EJB. Back to the wilds: Tapping evolutionary adaptations for resilient crops through systematic hybridization with crop wild relatives. Am J Bot. 2014. October 1;101(10):1791–800. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1400116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maxted N, Kell S. Establishment of a Global Network for the in situ Conservation of Crop Wild Relatives: Status and needs. Rome, Italy: FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture; 2009. October. (Background study paper). Report No.: 39. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bringhurst RS, Voth V. Origin and evolutionary potentiality of the day-neutral trait in octoploid Fragaria. Genetics. 1978;50:510. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horvath A, Sánchez-Sevilla J f., Punelli F, Richard L, Sesmero-Carrasco R, Leone A, et al. Structured diversity in octoploid strawberry cultivars: Importance of the old European germplasm. Ann Appl Biol. 2011. November 1;159(3):358–71. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakaya A, Isobe SN. Will genomic selection be a practical method for plant breeding? Ann Bot. 2012. May 29;mcs109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma X, Zhu Q, Chen Y, Liu Y-G. CRISPR/Cas9 platforms for genome editing in plants: Developments and applications. Mol Plant. 2016. July 6;9(7):961–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bauer A. Progress in breeding decaploid fragaria × vescana hybrids In: Schmidt H, Kellerhals M, editors. Progress in Temperate Fruit Breeding [Internet]. Springer; Netherlands; 1994. [cited 2014 Dec 4]. p. 189–91. (Developments in Plant Breeding). http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-011-0467-8_38 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chambers AH, Pillet J, Plotto A, Bai J, Whitaker VM, Folta KM. Identification of a strawberry flavor gene candidate using an integrated genetic-genomic-analytical chemistry approach. BMC Genomics. 2014. April 17;15(1):217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rousseau-Gueutin M, Richard L, Le Dantec L, Caron H, Denoyes-Rothan B. Development, mapping and transferability of Fragaria EST-SSRs within the Rosodae supertribe. Plant Breed. 2011;130(2):248–55. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rivarola M, Chan AP, Liebke DE, Melake-Berhan A, Quan H, Cheung F, et al. Abiotic stress-related expressed sequence tags from the diploid strawberry Fragaria vesca f. semperflorens. Plant Genome. 2011. March 1;4(1):12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cabrera A, Kozik A, Howad W, Arus P, Iezzoni AF, van der Knaap E. Development and bin mapping of a Rosaceae Conserved Ortholog Set (COS) of markers. BMC Genomics. 2009;10(1):562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Varshney RK, Graner A, Sorrells ME. Genic microsatellite markers in plants: Features and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2005. January;23(1):48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sato S, Isobe S, Asamizu E, Ohmido N, Kataoka R, Nakamura Y, et al. Comprehensive structural analysis of the genome of red clover (Trifolium pratense L.). DNA Res Int J Rapid Publ Rep Genes Genomes. 2005;12(5):301–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peakall R, Smouse PE. Genalex 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol Ecol Notes. 2006. March 1;6(1):288–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peakall R, Smouse PE. GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—an update. Bioinformatics. 2012. October 1;28(19):2537–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chapuis M-P, Estoup A. Microsatellite null alleles and estimation of population differentiation. Mol Biol Evol. 2007. March 1;24(3):621–31. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu K, Muse SV. PowerMarker: An integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2005. May 1;21(9):2128–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nei M, Tajima F, Tateno Y. Accuracy of estimated phylogenetic trees from molecular data. II. Gene frequency data. J Mol Evol. 1983;19(2):153–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of Phylogenetic Networks in Evolutionary Studies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006. February 1;23(2):254–67. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011. October;28(10):2731–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987. July;4(4):406–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003. August;164(4):1567–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Dominant markers and null alleles. Mol Ecol Notes. 2007. July 1;7(4):574–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01758.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hubisz MJ, Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inferring weak population structure with the assistance of sample group information. Mol Ecol Resour. 2009. September;9(5):1322–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02591.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000. June 1;155(2):945–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Earl DA, vonHoldt BM. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour. 2011. October 13;4(2):359–61. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005. July;14(8):2611–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martí AF i, Forcada CF i, Kamali K, Rubio-Cabetas MJ, Wirthensohn M, Company RS i. Molecular analyses of evolution and population structure in a worldwide almond [Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A. Webb syn. P. amygdalus Batsch] pool assessed by microsatellite markers. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2014. July 27;62(2):205–19. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Z, Kang M, Liu H, Gao J, Zhang Z, Li Y, et al. High-level genetic diversity and complex population structure of Siberian apricot (Prunus sibirica L.) in China as revealed by nuclear SSR markers. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2014. February 7 [cited 2016 Aug 2];9(2). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3917850/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arulsekar S, Bringhurst RS. Genetic model for the enzyme marker PGI in diploid California Fragaria vesca: Its variability and use in elucidating the mating system. J Hered. 1981. March 1;72(2):117–20. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Excoffier L, Foll M, Petit RJ. Genetic consequences of range expansions. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2009;40(1):481–501. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stanley L, Forrester NJ, Govindarajulu R, Liston A, Ashman T-L. Geographic patterns of genetic variation in three genomes of North American diploid strawberries with special reference to Fragaria vesca subsp. bracteata. Botany. 2015. June 11;93(9):573–88. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chambers A, Carle S, Njuguna W, Chamala S, Bassil N, Whitaker VM, et al. A genome-enabled, high-throughput, and multiplexed fingerprinting platform for strawberry (Fragaria L.). Mol Breed. 2013. March 1;31(3):615–29. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kalinowski ST. Do polymorphic loci require large sample sizes to estimate genetic distances? Heredity. 2004. August 25;94(1):33–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stefán Stefánsson. Flóra Íslands. 3rd ed Akureyri: Hið íslenzka náttúrufræðifélag; 1948. (In Icelandic). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Whole data set, including cultivars. (B) Eurasian samples without cultivars. (C) American samples only.

(TIF)

The tree is rooted to the two other species used in the study, F. chinensis and F. viridis. Information about bootstrap values above 50 that are not at the end of branches.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

Including marker name, sequence of forward and reverse primers, GenBank accession number (Acc. no.), pattern of repeats (Repeat), chromosome location (Chr.), the linkage position (Linkage), and species name.

(DOCX)

Nei’s genetic distance (below diagonal line) and pairwise population Fst values (above diagonal line) between groups.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

The microsatellite data has been deposited to the Dryad Repository at http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.t9d41. The full citation for the data package is “Hilmarsson H, Hytönen T, Isobe S, Toivainen T, Hallsson J. Data from: Molecular analysis of a global collection of Fragaria vesca using microsatellite markers confirms previous classification of North-American subspecies and shows great divergence between American and Eurasian groups."