Abstract

Characteristics of mosquito larval habitats are important in determining whether they can survive and successfully complete their developmental stages. Therefore, data on the ecological factors affecting mosquito density and abundance especially the physicochemical properties of water of their breeding sites, can possibly be helpful in implementing larval management programs. Mosquito larvae were collected using a standard 350 ml dipper from fixed habitats including: artificial pool, river edge, creek and etc, in 30 villages of 16 counties from May-December 2014. Water samples were collected during larval collection and temperature (°C), acidity (pH), turbidity (NTU), electrical conductivity (μS/cm), alkalinity (mg/l CaCO3), total hardness (mg/l), nitrate (mg/l), chloride (mg/l), phosphate (mg/l) and sulphate (mg/l) were measured using standard methods. Spearman correlation coefficient, Kruskal-Wallis test of nonparametric analysis, Chi-square (χ2) analysis, regression analysis and C8 interspecific correlation coefficient were used for data analysis. A total of 7,566 mosquito larvae belonging to 15 species representing three genera were collected from fixed larval breeding places. Culex pipiens was the dominant species except in four villages where An. maculipennis s.l. and Cx. torrentium were predominant. There was a significant positive correlation between the density of Cx. pipiens and electrical conductivity, alkalinity, total hardness and chloride, whereas no significant negative correlation was observed between physicochemical factors and larval density. The highest interspecific association of up to 0.596 was observed between An. maculipennis s.l/An. pseudopictus followed by up to 0.435 between An. maculipennis s.l/An. hyrcanus and An. hyrcanus/An. pseudopictus. The correlations observed between physicochemical factors and larval density, can possibly confirm the effect of these parameters on the breeding activities of mosquitoes, and may be indicative of the presence of certain mosquito fauna in a given region.

Author summary

Determination of association between mosquito larval abundance and physicochemical factors in aquatic habitats in Mazandaran Province was the purpose of this study. In 30 villages of 16 counties in the province, Culex pipiens, Cx. tritaeniorhynchus and An. maculipennis s.l. were the most abundant species discovered in larval habitats. The pair of species An. maculipennis s.l/An. pseudopictus has the highest interspecific association in the area. Culex pipiens showed the greatest compatibility compared with other species with a range of densities from the lowest to the highest in different habitats containing varying levels of physicochemical factors. Measuring physicochemical factors of water in larval habitats indicated that values of chloride, electrical conductivity, alkalinity and total hardness were significantly associated with the larval abundance in different larval habitats. The electrical conductivity, alkalinity, total hardness and chloride had significant positive correlation with the density of Cx. pipiens, whereas no negative correlation was obtained between larval density and physicochemical factors. These differences in preferences and association with varying levels of physicochemical factors can have vector-borne diseases control implications, because habitat changes through the manipulation of these factors to the detriment of vector species can ultimately lead to reduced abundance of vector species. The data may also be useful to predict changes in the densities of mosquito larvae or their transition should natural or artificial environmental modifications lead to alteration in the physicochemical factors.

Introduction

Water characteristics of breeding places are important for oviposition and development of mosquitoes [1]. Different characteristics of the oviposition sites such as: vegetation, temperature, turbidity, pH, concentration of ammonia, nitrite and nitrate, sulphate, phosphate, chloride, calcium, and water hardness affect mosquito larval density [2–4]. Changing these factors in larval habitats may create conditions favorable or unfavorable for mosquito biology [5]. Temperature lower than 14–16°C and higher than 30°C reduces the rate of larval development of many species [2,6]. Larvae of most mosquito species are found in nature in pH 3.3–10.5 [2]. Studies in several micro and macrohabitats have revealed that distribution of Cx. pipiens, Cs. longiareolata, Cx. antennatus, Oc. caspius, Cx. vagans, Cx. decens, Cx. perexiguus, Cx. univittatus, An. multicolor are directly correlated with temperature, ammonia, nitrate, pH, dissolved oxygen and salinity [7,8]; An. culicifacies with temperature and dissolved oxygen [1,9]; Ae. albopictus with conductivity, total dissolved solids, nitrate, phosphate, sulphate, turbidity and salinity [10,11]; and An. varuna with calcium [1]. While larval densities of Cx. pipiens, Cx. perexiguus and Ae. albopictus are not directly affected by total nitrogen content, salinity and turbidity [8,10,11]. Dissolved nitrogen content can be a limiting factor on larval growth of the genus Aedes (formerly Ochlerotatus) by indirect effects on the trophic structure of tree-hole environments [12]. Although abundance of larvae can be associated with the soluble nitrate and phosphate levels in an area [13], it can equally be independent of those in another area because the nitrogen or phosphorus in water bodies can result in eutrophication and oxygen depletion, harmful algal blooms, toxic effects on fish and some aquatic organisms and overall reductions in aquatic biodiversity [4,14]. Therefore other factors can be effective in predicting larval density in different areas [15]. For example, the vegetation of mosquito larval habitats is considered as an important factor in the process of egg-laying and density of mosquito larvae [16]. Tall emergent aquatic plants can cover the surface and decrease mosquito larval density by acting as a barrier for egg-laying female. They may cause microbial growth and produce a high variety of predators [17].

Not much data currently exists regarding the physiochemical characteristics of mosquito larval habitats in Iran. Most of the available data is on anopheline mosquito larval habitats. The distribution of An. sacharovi is significantly associated with calcium bicarbonate, sodium sulphate and salinity in larval habitats in Ardebil Province, northwestern Iran[18]. Larval density of An. culicifacies s.l., An. dthali, An. stephensi, An. superpictus, An. fluviatilis s.l., An. turkhudi, An. moghulensis, and An. apoci is associated with temperature, EC, alkalinity, chloride and sulphate, total hardness, and dry residues in Bashagard and Rudan district, southern Iran [15,19]. A significant difference was observed between the density of An. culicifacies and phosphate, calcium and EC; An. turkhudi and pH, total hardness and nitrate; An. superpictus and total hardness and nitrate; An. stephensi and nitrate, An. multicolor and pH and sulphate in Iranshahr, southwestern Iran [20]. Temperature, pH, turbidity, EC, TDS, alkalinity, total hardness, calcium, chloride, fluoride, nitrite, nitrate, phosphate, sulphate were not significantly correlated with An. claviger, An. marteri, An. superpictus, An. turkhudi, Cx. arbieeni, Cx. hortensis, Cx. mimeticus, Cx. modestus, Cx. pipiens, Cx. territans, Cx. theileri, Cs. longiareolata, Cs. subochrea, Oc. caspius s.l. in Qom Province, central Iran [21]

To date, there is no information on physicochemical characteristics of mosquito larval habitats and coefficient of interspecific association (C8) in Mazandaran Province and this is the first such study in the province. Differences in environmental and geographical characteristics of the North of Iran in comparison with other provinces of the country have caused a fertile environment for the development of mosquitoes. The area had a history of diseases transmitted by vectors, the most important of which has been Malaria. Mazandaran has a unique environment fit for migratory birds and thousands of different wild bird species that spend winter in numerous fresh water lakes and wetlands across the province. West Nile virus is circulating in the province between the migratory birds and humans mostly by Culex mosquitoes [22,23]. Also, the environment may allow the invasion and establishment of Aedes vectors of dengue and Zika based on the risk assessment of the latter, a huge national research activity is underway to verify the risk. Information on the ecological factors affecting mosquito larval biology such as the physicochemical properties of the water of the breeding places and interspecific associations are important in survival, spatio-temporal distribution [24], biodiversity, affinity and association indices of disease vectors [25–27]. The information may serve as the basis for designing and implementation of adequate vector control programs [28]. Despite the voluminous literature on the distribution of mosquito larvae and physicochemical factors, the data set seems to be inconclusive in leading to a prediction of the presence of larvae in different habitats. Therefore more studies and systematic reviews with proper generalization are required. The present study was conducted to document the relationship between physicochemical characteristics of mosquito larval habitats and the presence or absence of a given species, density or diversity and interspecific associations of larvae in different habitats in Mazandaran Province.

Methods

Ethics statement

This research has been approved by the Ethic committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences under the code 1017.

Study area

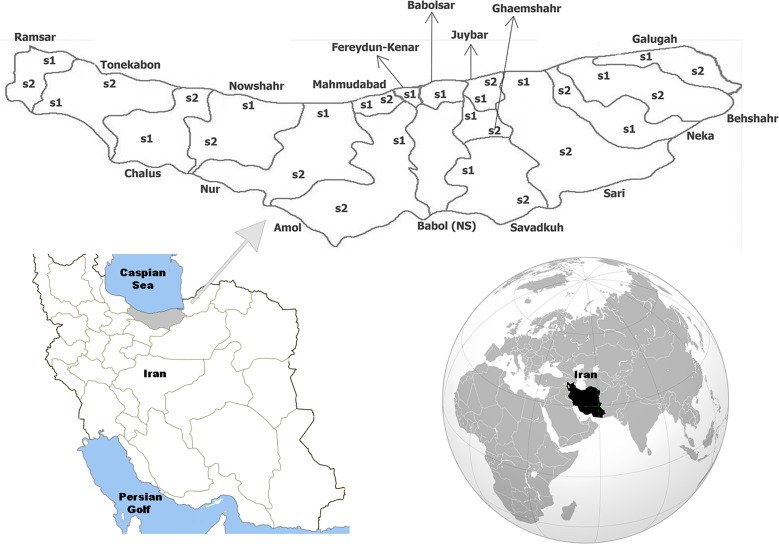

The study was carried out from May to December 2014 in Mazandaran Province located within the latitude of 35° 47′- 36° 35′ N and longitude of 50° 34′–54° 10′ E (Fig 1). The province has an area of 23756.4 km2 and a population of 3,073,943 (2011 census) [29]. It is located between Golestan Province in the East, Gilan Province in the West, Caspian Sea in the North and Tehran and Semnan Provinces in the South. The inhabitants are mainly involved in agriculture, animal husbandry, production of farmed fish and tourism industry. The climate varies from mild and humid in the Caspian Sea shore to moderate and cold in mountainous regions. The minimum and maximum mean annual temperatures and rainfall ranges between 1.2–29.2°C and 0–755.6 mm, respectively.

Fig 1. Map shows sampling places in various counties and villages of Mazandaran Province (s1 and s2 stand for station 1 and station 2).

These comprise: Galugah County (s1: Nezammahale, s2: Tileno villages), Behshahr (s1: Hossein Abad, s2: Al Tappeh), Neka (s1: Chalmardi, s2: Komishan), Sari (s1: Qajar Kheil, s2: Dallak Kheil), Ghaemshahr (s1: Rostam kola, s2: Shahrud Kola), Savadkooh (s1: Sorkh Kola, s2: Andar Koli), Juybar (s1: Astanesar, s2: Pain Zarrin Kola), Babolsar (s1: Kikha Mahalleh), Fereydunkenar (s1: Firuzabad), Amol (s1: Qadi Mahalleh, s2: Razakeh), Mahmudabad (s1: Galesh Pol, s2: Bishe Kola), Noor (s1: Abbasa, s2: Karat Koti), Noshahr (s1: Aliabad Mir, s2: Shofeskaj), Chalos (s1: Sinava, s2: Zavat), Tonekabon (s1: Asadabad, s2: Soleymanabad) and Ramsar (s1: Shah Mansur Mahale, s2: Potak). Babol (NS: no sampling).

Mosquito collection and identification

Mosquito larvae were collected by standard 350 ml dipper from fixed oviposition sites (breeding places with permanent water during the sampling period) such as artificial pools, river edge, creek, marsh, large metal bucket, abandoned wells, water canals, pit with plastic floor (Fig 2), in 30 villages of 16 counties across the province (Fig 1). In each village, one fixed station was selected and visited for larval collection once a month. It is important to mention that one hundred staff members of the Mazandaran health centers were recruited and trained during two theoretical and practical workshops before undertaking sample collection. We met with county and village councils to seek cooperation of the villagers for assistance with sampling team. Collected larvae were conserved in lactophenol and were transferred to the Medical Entomology Laboratory at Faculty of Health, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. In the laboratory, microscope slides were prepared from each of the specimens using Berlese’s medium and larvae were identified by morphological characteristics according to appropriate keys [30,31].

Fig 2. A variety of fixed habitats of mosquito larvae in Mazandaran Province, 2014 (Original photo).

Physicochemical analyses

Water samples were collected from the same 30 fixed larval habitats in which dip samples had been collected in designated villages and were kept in one liter appropriately labeled polyethylene bottles. The bottles were placed inside an ice box and were sent for analysis to the Faculty of Health. Temperature (°C), acidity (pH), turbidity (NTU), electrical conductivity (EC) (Micro-Simens/cm) (μS/cm), alkalinity (mg/l CaCO3), total hardness (mg/l), nitrate (mg/l), chloride (mg/l), phosphate (mg/l) and sulphate (mg/l) of the water were measured. Water temperature and pH were measured on site using a thermometer and pH probe (Eutech-Cyberscan PH5500), turbidity using a turbidimeter device (2100P Portable Turbidimeter at Hach), EC using a conductometer device (EC LYTIC-AQUA (CON200) before dipping. Alkalinity, total hardness and chloride were determined using direct titration techniques and nitrate, sulphate and phosphate were measured using a spectrophotometer device (Perkinelmer UV/Visible Lambda EZ201 and HACH). All analyses were conducted according to the standard methods used in Rice et al. [32].

Statistical analysis

The species data from each site was summed up and collectively reported in a graph. The means and standard deviations of physicochemical parameters of each breeding site was calculated using SPSS software version 19. The presumption for normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The physicochemical parameters among sites were compared by Kruskal-Wallis test of nonparametric analysis. Chi-square (χ2) analysis was performed to determine whether there was any significant difference in distribution of the species in different counties. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to examine the relation of the mosquito larval densities to the physicochemical factors adjusted by types of habitats. Regression analysis between larval densities and physicochemical factor were also performed to clarify the relationship and r-squared values were calculated.

Interspecific association

Hurlbert’s coefficient of interspecific association (C8) was used to measure the associations between co-occurring species using presence-absence data. Values of C8 range from -1 to +1 for negative and positive associations, respectively. Positive associations between species can probably show a common habitat preference or interspecific attraction, whereas negative associations may reveal different habitat preferences or interspecific repulsion. The formula used for calculating C8 is as follows:

where a, b, c, and d are the values in four cells of a 2 × 2 contingency table; Obs χ2 is referred to the value of χ2 associated with the observed values of a, b, c and d; Max χ2 is referred to the value of χ2 when a is as large (if ad ≥bc) or as small (if ad < bc) as the marginal totals of the 2 × 2 table permit; Min χ2 is referred to the value of χ2 when the observed a differs from its expected value (â) by less than 1.00 [33].

Results

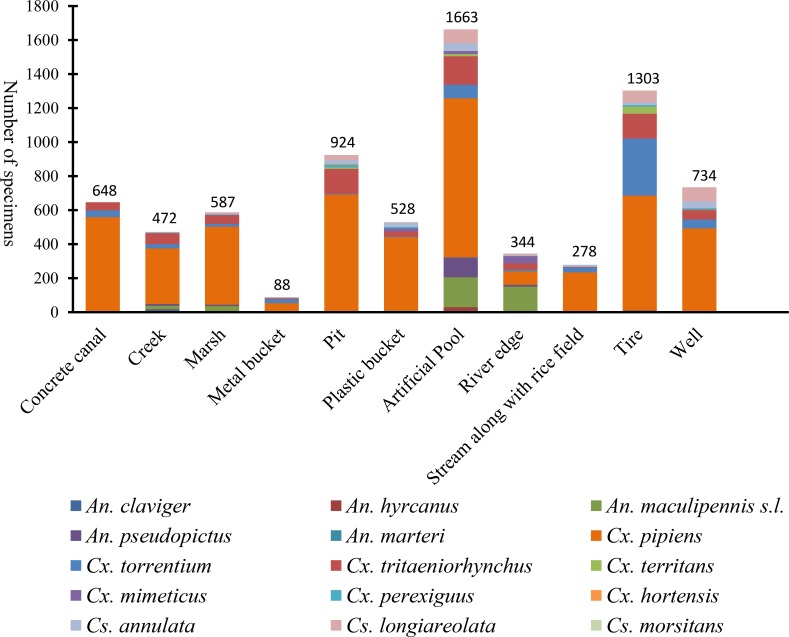

A total of 7,566 mosquito larvae from three genera and 15 species were collected from eleven different types of fixed oviposition sites. Using random effect model, it is observed that habitats type affect the abundance of species (P < 0.05). Culex pipiens (56.22%), Cx. tritaeniorhynchus (10.05%) and An. maculipennis s.l. (10.50%), were the most abundant species observed in artificial pool. whereas, An. marteri (0.06%), Cx. hortensis (0.15%) and Cs. morsitans (0.08%) were relatively uncommon in habitats such as concrete canal, artificial pool and tire; respectively (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Composition of the mosquito larvae collected from eleven types of fixed larval habitats in Mazandaran Province, May- December 2014.

Using the coefficient of interspecific association (C8), significant positive associations was determined between An. maculipennis s.l/An. hyrcanus and An. hyrcanus/An. pseudopictus of up to 0.435. This coefficient was up to 0.596 between An. maculipennis s.l/An. pseudopictus (Table 1).

Table 1. Coefficients of interspecific association (C8) for larvae of different species in eleven types of fixed habitats in Mazandaran Province, May-December 2014.

|

Species |

An. Claviger | An. hyrcanus | An. maculipennis s.l | An. pseudopictus | An. marteri | Cx. pipiens | Cx. torrentium |

Cx. tritaeniorhynchus |

Cx. territans | Cx. mimeticus | Cx. perexiguus | Cx. hortensis | Cs. annulata | Cs. longiareolata | Cs. morsitans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An. Claviger | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| An. hyrcanus | * | 0.435 | 0.435 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| An. maculipennis s.l | * | 0.596 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| An. pseudopictus | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| An. marteri | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Cx. pipiens | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Cx. torrentium | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Cx. tritaeniorhynchus | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Cx. territans | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Cx. mimeticus | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Cx. perexiguus | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Cx. hortensis | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| Cs. annulata | * | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||

| Cs. longiareolata | * | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| Cs. morsitans | * | |||||||||||||||

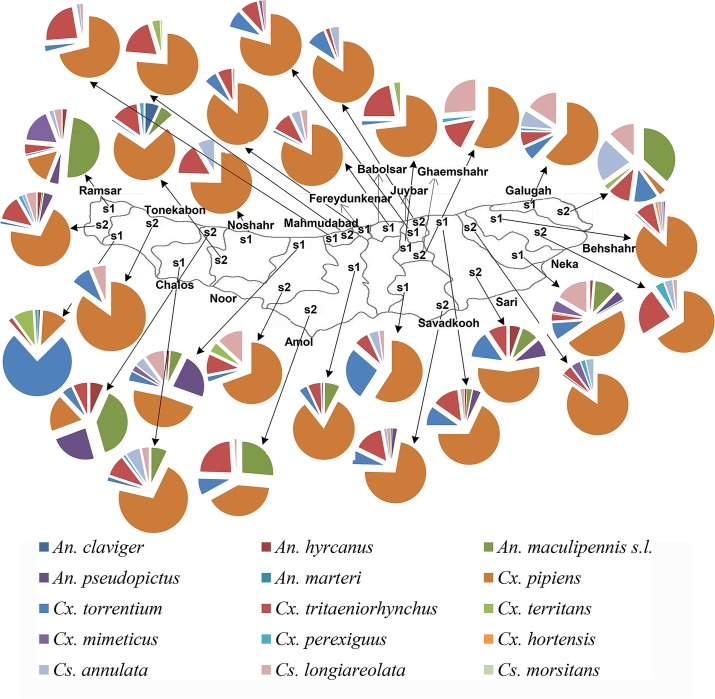

There are significant differences in the distribution of the species in spatial scale (P < 0.05). Culex pipiens had the largest distribution and was the dominant species in all villages except Tileno, Zavat, Asad Abad and Shah Mansur Mahale. The highest and the lowest number and percentage of Cx. pipiens were recorded in the villages of Firozabad (558, 86.11%) and Tileno (3, 3.26%), respectively.

Culex tritaeniorhynchus was dispersed in all villages except Abbasa and Soleymanabad and showed the highest abundance in the village of Al Tappeh (95, 24.05%). Anopheles maculipennis s.l. were the dominant anopheline in the villages of Tileno, Zavat and Shah Mansur Mahale and showed the highest dispersion rate compared to the rest of the Anopheles. Culiseta morsitans and An. marteri showed the lowest distribution in the villages of Bishekola (0.76%) and Chalmardi (0.40%). Data regarding distribution of other species in spatial scale are shown in Fig 4.

Fig 4. Distribution and number of mosquito larvae collected from fixed habitats in villages of Mazandaran Province, May- December 2014.

Means and standard deviations of the physicochemical factors from larval habitats in different villages were calculated for each species. Culiseta morsitans was found in breeding sites with higher pH up to 7.44. It prefers lower temperature, alkalinity, nitrate, chloride and phosphate. Anopheles marteri prefers higher turbidity, alkalinity, total hardness, phosphate and sulphate, while An. claviger, Cx. mimeticus and Cx. perexiguus breed in habitats with higher temperature, EC and chloride, respectively. Culex mimeticus, Cx. hortensis, Cx. torrentium and An. claviger were collected in habitats with the lowest ranges of pH (6.88±0.40), turbidity (12.50±0.70), EC (69.42±1051.15), total hardness (192) and sulphate (14.18), respectively (Table 2). Ranges of the physicochemical parameters of larval habitats of different species are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations of physicochemical characteristics, along with occurrence of mosquito species in different larval habitats in Mazandaran Province, May-December 2014.

| Occurrence in villages | Temperature (°C) |

Acidity (pH) | Turbidity (NTU) |

Electrical conductivity (μS/cm) | Alkalinity (mg/l CaCO3) |

Nitrate (mg/l) | Total hardness (mg/l) | Chloride (mg/l) |

Phosphate (mg/l) |

Sulphate (mg/l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An. claviger (1) | 18 | 7.35 | 21 | 496 | 204 | 0.840 | 192 | 85.97 | 0.558 | 14.18 |

| An. hyrcanus (7) | 17.29± 0.95 | 7.22±0.35 | 42.57±62.72 | 705.71±832.65 | 245.14±179.31 | 2±2.24 | 372.57±331.11 | 134.10±267.26 | 0.99±1.22 | 117.77±156.58 |

| An. maculipennis s.l. (14) | 17.29±1.13 | 7.24±0.33 | 32.64±46.27 | 613.21±614.68 | 222.29±140.30 | 1.96±2.49 | 502.00±614.68 | 94.04±187.77 | 0.67±0.94 | 102.93±130.81 |

| An. pseudopictus (10) | 17.30±1.05 | 7.25±0.34 | 33.30±53.41 | 712.20±766.61 | 244.90±167.73 | 1.87±1.87 | 336.80±288.27 | 144.15±251.81 | 0.86±1.05 | 101.23±135.34 |

| An. marteri(1) | 16.00±0 | 7.6±0 | 97.00±0 | 1109.00±0 | 500.00±0 | 5.23±0 | 716.00±0 | 102.96±0 | 3.20±0 | 446.18±0 |

| Cx. pipiens(30) | 16.33±2.35 | 7.13±0.42 | 34.97±65.15 | 850.10±994.24 | 239.63±149.66 | 2.10±2.92 | 450.80±466.48 | 353.82±942.00 | 0.54±0.82 | 101.87±96.92 |

| Cx. torrentium(26) | 16.50±2.12 | 7.12±0.45 | 38.23±69.42 | 69.42±1051.15 | 248.81±158.39 | 2.00±2.85 | 479.23±494.97 | 211.54±366.40 | 0.52±0.76 | 102.62±101.02 |

| Cx. tritaeniorhynchus(28) | 16.25±2.41 | 7.14±0.44 | 36.96±67.06 | 885.43±1020.51 | 244.46±152.06 | 1.87±2.53 | 465.57±478.88 | 478.88±971.88 | 0.47±0.78 | 105.71±99.27 |

| Cx. territans(6) | 14.67±2.94 | 6.97±0.50 | 81.17±126.42 | 614.00±446.94 | 265.33±144.43 | 2.33±2.99 | 440±332.19 | 58.14±36.91 | 0.85±1.24 | 188.84±156.99 |

| Cx. mimeticus(7) | 16.57±0.97 | 6.88±0.40 | 29.71±33.97 | 1430.86±1395.97 | 336±227.69 | 3.26±2.97 | 588±386.43 | 332.03±517.66 | 1.15±1.21 | 155.50±142.36 |

| Cx. perexiguus(8) | 16.88±1.35 | 7.11±0.17 | 19±12.87 | 748.88±1139.53 | 239.50±216.74 | 2.38±2.75 | 612.50±812.35 | 826.24±1751.24 | 0.43±0.79 | 122.64±102.50 |

| Cx. hortensis (2) | 17 | 7.00±0.78 | 12.50±0.70 | 1169.50±590.43 | 368.50±96.87 | 1.37±0.27 | 440±39.59 | 279.41±273.56 | 0.58±0.10 | 146.13±4.94 |

| Cs. annulata (15) | 16.27±2.40 | 7.17±0.37 | 16.20±14.42 | 899.80±1116.41 | 253.67±174.98 | 1.24±1.45 | 537.60±607.43 | 572.28±1297.94 | 0.57±0.84 | 77.36±79.12 |

| Cs. longiareolata (20) | 16.05±2.06 | 7.13±0.46 | 35.95±73.21 | 761.55±824.98 | 231.25±128.02 | 2.02±2.95 | 474.40±514.07 | 388.47±1105.26 | 0.63±0.93 | 113.16±108.03 |

| Cs. morsitans (1) | 10 | 7.44 | 21 | 419 | 168 | 0.30 | 300 | 45.98 | 0 | 164.54 |

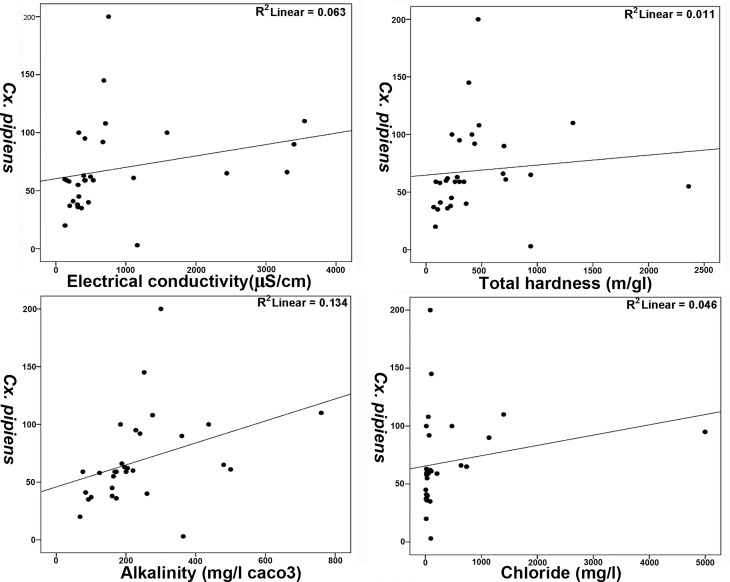

Positive correlation exists between the larval abundance of Cx. pipiens and the physicochemical characteristics including EC, alkalinity, total hardness and chloride with Spearman rank correlations of 0.575 (P<0.001), 0.617 (P<0.001), 0.495 (P<0.005) and 0.539 (P<0.002), respectively. However, there was no significant negative correlation between physicochemical characteristics and larval abundance (Table 3). The regression relationship (R2) between Cx. pipiens and EC, alkalinity, total hardness and chloride were 0.11, 0.20, 0.01 and 0.06, respectively which is shown by Scatter plot (Fig 5).

Table 3. Correlation coefficient between larval density and physicochemical properties of larval habitats adjusted by the habitats types in Mazandaran Province, August 2014.

| Species | Temperature (°C) |

Acidity (pH) | Turbidity (NTU) |

Electrical conductivity (μS/cm) | Alkalinity (mg/l CaCO3) |

Nitrate (mg/l) | Total hardness (mg/l) | Chloride (mg/l) | Phosphate (mg/l) |

Sulphate (mg/l) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An. claviger | Correlation Coefficient | 0.174 | 0.118 | 0.107 | 0.054 | 0.032 | 0.011 | -0.150 | 0.086 | 0.141 | -0.268 |

| Sig. | 0.357 | 0.534 | 0.572 | 0.778 | 0.866 | 0.955 | 0.428 | 0.652 | 0.456 | 0.152 | |

| An. hyrcanus | Correlation Coefficient | 0.240 | 0.147 | 0.011 | -0.184 | -0.110 | 0.031 | -0.150 | -0.263 | 0.186 | -0.054 |

| Sig. | 0.201 | 0.440 | 0.955 | 0.330 | 0.562 | 0.871 | 0.428 | 0.160 | 0.325 | 0.776 | |

| An. maculipennis s.l. | Correlation Coefficient | 0.346 | 0.241 | 0.113 | -0.126 | -0.099 | 0.111 | -0.079 | -0.241 | 0.146 | -0.095 |

| Sig. | 0.061 | 0.200 | 0.553 | 0.507 | 0.604 | 0.561 | 0.677 | 0.199 | 0.441 | 0.618 | |

| An. pseudopictus | Correlation Coefficient | 0.274 | 0.226 | -0.023 | -0.152 | -0.042 | 0.093 | -0.168 | -0.298 | 0.245 | -0.115 |

| Sig. | 0.142 | 0.229 | 0.904 | 0.422 | 0.825 | 0.627 | 0.376 | 0.109 | 0.192 | 0.544 | |

| An. marteri | Correlation Coefficient | -0.098 | 0.268 | 0.269 | 0.182 | 0.290 | 0.226 | 0.225 | 0.140 | 0.315 | 0.311 |

| Sig. | 0.606 | 0.152 | 0.151 | 0.335 | 0.120 | 0.231 | 0.231 | 0.462 | 0.090 | 0.094 | |

| Cx. pipiens | Correlation Coefficient | -0.110 | -0.271 | 0.044 | 0.575 | 0.617 | 0.077 | 0.495 | 0.539 | -0.024 | 0.321 |

| Sig. | 0.562 | 0.147 | 0.819 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.684 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.901 | 0.084 | |

| Cx. torrentium | Correlation Coefficient | 0.099 | 0.040 | 0.113 | 0.194 | 0.145 | -0.139 | 0.146 | -0.122 | -0.075 | 0.174 |

| Sig. | 0.602 | 0.834 | 0.552 | 0.305 | 0.444 | 0.463 | 0.440 | 0.520 | 0.692 | 0.358 | |

| Cx. tritaeniorhynchus | Correlation Coefficient | -0.219 | -0.131 | -0.240 | 0.287 | 0.227 | 0.130 | 0.136 | 0.320 | -0.322 | 0.203 |

| Sig. | 0.245 | 0.490 | 0.201 | 0.124 | 0.228 | 0.492 | 0.475 | 0.085 | 0.082 | 0.282 | |

| Cx. territans | Correlation Coefficient | -0.316 | -0.312 | 0.092 | -0.130 | -0.001 | -0.048 | -0.085 | -0.150 | -0.017 | 0.134 |

| Sig. | 0.088 | 0.094 | 0.629 | 0.495 | 0.996 | 0.802 | 0.655 | 0.428 | 0.930 | 0.479 | |

| Cx. mimeticus | Correlation Coefficient | -0.072 | -0.201 | 0.044 | 0.262 | 0.232 | 0.220 | 0.254 | 0.136 | 0.277 | 0.221 |

| Sig. | 0.706 | 0.287 | 0.816 | 0.162 | 0.218 | 0.243 | 0.175 | 0.475 | 0.139 | 0.240 | |

| Cx. perexiguus | Correlation Coefficient | -0.019 | -0.132 | 0.044 | -0.047 | -0.020 | 0.312 | -0.165 | 0.059 | 0.306 | -0.315 |

| Sig. | 0.920 | 0.486 | 0.818 | 0.806 | 0.916 | 0.094 | 0.382 | 0.755 | 0.100 | 0.090 | |

| Cx. hortensis | Correlation Coefficient | 0.033 | 0.247 | -0.032 | 0.225 | 0.247 | 0.075 | 0.097 | 0.204 | 0.098 | 0.139 |

| Sig. | 0.864 | 0.188 | 0.866 | 0.231 | 0.189 | 0.693 | 0.612 | 0.280 | 0.607 | 0.462 | |

| Cs. annulata | Correlation Coefficient | 0.062 | -0.090 | 0.056 | 0.086 | 0.170 | -0.180 | 0.205 | 0.180 | 0.141 | -0.139 |

| Sig. | 0.744 | 0.636 | 0.769 | 0.651 | 0.370 | 0.342 | 0.277 | 0.341 | 0.459 | 0.464 | |

| Cs. longiareolata | Correlation Coefficient | -0.348 | -0.138 | -0.049 | -0.103 | 0.106 | -0.041 | 0.057 | -0.013 | 0.199 | 0.171 |

| Sig. | 0.060 | 0.468 | 0.796 | 0.588 | 0.577 | 0.831 | 0.764 | 0.945 | 0.291 | 0.365 | |

| Cs. morsitans | Correlation Coefficient | -0.294 | 0.161 | 0.107 | 0.011 | -0.118 | -0.097 | 0.000 | -0.032 | -0.228 | 0.182 |

| Sig. | 0.115 | 0.395 | 0.572 | 0.955 | 0.534 | 0.611 | 1.000 | 0.866 | 0.225 | 0.335 |

Fig 5. Regression relationships between Cx. pipiens and EC, alkalinity, total hardness and chloride of larval habitats in Mazandaran Province, August 2014.

Discussion

Different factors influence the abundance and distribution of mosquito species including physicochemical factors, interspecific association, climate, vegetation, sources of nutrients and human activities [34]. The effects of physicochemical factors on the density of mosquito larvae were examined for the first time in Mazandaran Province, northern Iran.

Culex pipiens proved to be the dominant species in the province and its larvae were collected from all counties in the province, whereas Cx. tritaeniorhynchus and Cx. torrentium were not collected in a few localities. In a study by Nikookar et al., [35–37] across Mazandaran Province, Culex pipiens was the dominant species and Zaim [38] reported this species from 24 provinces of Iran. Compatibility of Cx. pipiens to different types of oviposition sites in the vicinity of human places with various degrees of physicochemical factors (especially degree of organic contamination, for example, ammonium ion) and suitable vegetation can probably be important in their interspecific interactions and justify its wide distribution in different counties of the province [16,39–41].

The most abundant anopheline species was An. maculipennis s.l., however, it was not collected from 16 villages in the province. A significant association between the abundance of An. maculipennis s.l. and all physicochemical factors was not observed in this study. It seems that changes in the agricultural patterns such as replacing rice cultivation with citrus gardens, reduced cattle husbandry (sources of blood for zoophilic behavior of adults of this species) are contributing factors to failure in collection of this species in some localities [42,43]. Anopheles maculipennis was reported to be the most common anopheline species in some provinces in the north and northwest of Iran [44–47].

Although no interspecific association was observed between Culex species, a number of such associations were observed between anophelines. The interspecific association coefficient for pairs of species An. maculipennis s.l/An. pseudopictus was the highest in Mazandaran Province followed by An. maculipennis s.l/An. hyrcanus and An. pseudopictus/An. hyrcanus. These species are “controphic species” and have common needs in a variety of habitats. It is affecting the biology, ecology and development of larvae because of competition for food, exposure to predators and susceptibility to pesticides. However, the relationship between controphic species (conspecific or heterospecific) that live together in a common habitat could be important in identifying vector habitats and also help the design and implementation of appropriate principles of vectors control programs [48].

In different studies in Iran, significant positive associations were detected (using coefficients other than C8) between the pairs of species An. culicifacies/An. dthali in Bashagard District, southern Iran [19], An.dthali/An.turkhudi in Isfahan Province [49] and An. hyrcanus/An. pseudopictus in Mazandaran Province, North of Iran [35]. The authors argued that these relationships are due to the same preferences in the choice of habitats and common food needs which are consistent with the results of the present study.

Culex pipiens showed a significant positive correlation with EC, alkalinity, total hardness and chloride. It is likely that changes in the cultivation of agricultural land for example converting them into citrus groves, as well as the use chemical fertilizers in the province, can alter the physicochemical characteristics of the water in the larval habitats, changes that may, in turn, alter the abundance of the species larvae [50]. These physicochemical parameters will be used as an energy source to increase the proliferation of algae and other micro-organisms (including bacteria) that serve as the main food for larvae [51], and provide chemical cues for choosing a suitable oviposition site by females and stimulate egg hatch [50]. It can also possibly lead to the interspecific interactions and mosquito community structure and its relationship to the risk of infectious diseases transmission in specific ecosystems [52].

As mentioned above, physicochemical factors are nutritional sources of water bodies. However, an excessive rise can have adverse effects on some aquatic organisms and subsequently reduce larval food sources [53]. For example, sulfate is a natural substance which includes sulfur and oxygen. It may be washed from the soil and added by other sources including decaying plant and animal matter, industrial and domestic sewages and farmland runoff in most water supplies [4]. A high level of sulphate showed significant influence on the abundance of An. arabiensis mosquito larvae [4].

A significant difference was observed between the density of An. culicifacies and calcium and EC; An. turkhudi and An. superpictus and total hardness in Sistan and Baluchestan Province of Iran. The authors believed that the larvae of An. culicifacies and An. turkhudi are more sensitive to physicochemical factors in different habitats compared with other species; this may explain the limited spread of the species in the country and the region [20] which is in agreement with our study.

In contrast with our research, no significant relationship was found between the abundance of the genera Anopheles, Culex and Aedes (formerly Ochlerotatus) with physicochemical and microbial parameters in Qom Province (central) and Bashagard district, southern Iran [19,21] and Egypt [7].

Even though other factors including temperature, pH, turbidity, nitrate, sulphate and phosphate from the mosquito larvae oviposition site did not show relationship with larval density after statistical analysis, their roles could not be disregarded. As is evident in others studies, there are a positive correlation between Cx. pipiens, Cs. longiareolata, Cx. antennatus, Oc. caspius, Cx. vagans, Cx. decens, Cx. perexiguus, Cx. univittatus, An. multicolor and temperature, pH and nitrate [7,8]; An. arabiensis and turbidity [17]; An. sinensis and sulphate [4]; Culex quinquefasciatus and phosphate [51].

A study on physicochemical characteristics of larval habitats and mosquito larval density in India revealed, although not significant, a positive correlation with pH and DO, whereas salinity, TDS and turbidity were negatively correlated with abundance of Ae. albopictus, Cx. quinquefasciatus, Armigeres subalbatus, Ae. aegypti, Toxorhynchites sp and Lutziasp larvae in containers, whilst significant negative correlation was noted between conductivity and larval density [54]. The investigators believed that these factors can be considered as predictor variables for density of mosquito larvae. This opinion is almost in agreement with our study that shows the importance of physicochemical factors in survival and population dynamics of mosquitoes, but this prediction value of physicochemical characteristics of larval habitats and mosquito larval density requires more investigation.

Although Culex tritaeniorhynchus was the second most abundant Culex species in the present study, the values of physicochemical factors were not helpful in explaining its abundances in our study. Culex tritaeniorhynchus prefers niches with wet muddy bottom emergent plant coverage and deeper water [24,55]. Therefore, this may indicate that other factors are involved in abundance of this species in the province.

As discussed, some of the data presented in others studies are in agreement [1,4,7,9] and some in contradiction [21] with the results of the present study which could be due to biological characteristics of different species that show different levels of tolerance to physicochemical factors.

As mentioned above, Culex pipiens is the most common specie across the province. It has generally been considered as an ornithophilic species and the most competent vector of WNV [56]. The species is opportunistic and bites both humans and animals; so, it can have the role of bridge vector between birds and humans and animals [57]. The wetlands are the prime locations for the emergence of the disease [58]. Detection of WNV in the mosquito populations and records of human infection with the virus in North and North West Iran [22,23] and availability of wetlands to migrating birds in Mazandaran Province may provide the ground for the entry and spread of the virus in the province. Biotic attributes such as the abundance and diversity of the host and abiotic conditions including physicochemical factors of the water are determinant factors in the epidemiology of West Nile fever [59].

Considering the impact of physicochemical factors on mosquito larval density, any changes in these factors without causing any negative effect on other forms of aquatic life, could possibly be considered as the basis for larval control strategies [17]. This also helps guide the public health efforts to prevent proliferation of the vectors of diseases including West Nile fever in the area. However, more investigation is needed on pathogens, predators, coverage of canopy, surface debris, algae and emergent plants in order to obtain solid evidence and get baseline information on mosquito larval habitat characteristics that may eventually be used for mosquito control programs. Environmental assessments should be considered before modifications such as alteration in cultivation, changes in the fertilizers used, environmental pollution and etc. are implemented in an area as they may change the abundance of the mosquito larvae.

Conclusion

In conclusion, based on the findings of the present study, physicochemical factors of breeding sites including EC, alkalinity, total hardness and chloride may determine the distribution and abundance of Cx. pipiens in the area. Although seems important and expected to be observed, a significant positive correlation has not been detected for the rest of the species present in the study area. High interspecific association between pair of species An. maculipennis s.l/An. pseudopictus show that these species have common needs and adaptability for sympatry. These findings could be useful in comprehending the ecology of mosquito larvae that may be beneficial in designing and implementing larval control programs. This is the first study looking at the physicochemical parameters associated with larval abundance and diversity in Mazandaran Province. Further studies are needed to enable the use of this information in vector control programs with confidence.

Limitations

It should be noted that there is a limitation to this study and that is we measured the physicochemical parameters only once in the whole of the study areas and sampling locations whereas the density of mosquito larvae measured every month. The possibility of relation of larval habitats physicochemical parameters and larval density fluctuation might have well been established should the trend of changes of the physicochemical parameters be determined, this has further research implications.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to 100 personnel of Mazandaran Provincial Health Deputy for their direct involvement in field collection of mosquito specimens. Thanks also to the residents of the villages for their kind cooperation with sampling teams during the study. Word of appreciation to Ms. Taheri and Ahangari for their assistance in conducting the experiments at the Environmental Health Laboratory. The results presented here is part of the Ph.D. thesis of the first author.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This research is supported by the Deputy for Research and Technology of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences with grant (No. 93-1017) received by Professor Ahmad Ali Enayati. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Piyaratne MK, Amerasinghe F, Amerasinghe P, Konradsen F. Physico-chemical characteristics of Anopheles culicifacies and Anopheles varuna breeding water in a dry zone stream in Sri Lanka. J Vector Borne Dis. 2005;42: 61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clements A. Vol. 1: Development, nutrition and reproduction. London [etc]: Chapman & Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mutero CM, Wekoyela P, Githure J, Konradsen F. Ammonium sulphate fertiliser increases larval populations of Anopheles arabiensis and culicine mosquitoes in rice fields. Acta Trop. 2004;89: 187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu XB, Liu QY, Guo YH, Jiang JY, Ren DS, Zhou GC, et al. Random repeated cross sectional study on breeding site characterization of Anopheles sinensis larvae in distinct villages of Yongcheng City, People’s Republic of China. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:58 doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amerasinghe F, Indrajith N, Ariyasena T. Physico-chemical characteristics of mosquito breeding habitats in an irrigation development area in Sri Lanka. Cey J Sci (Biol. Sci.). 1995;24: 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muirhead-Thomson RC. Mosquito Behaviour in Relation to Malaria Transmission and Control in the Tropics: Arnold. 1951.

- 7.Ibrahim AEA, El-Monairy OM, El-Sayed YA, Baz MM. Mosquito breeding sources in Qalyubiya Governorate, Egypt. Egypt Acad J Biolog Sci. 2011;3: 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenawy M, Ammar S, Abdel-Rahman H. Physico-chemical characteristics of the mosquito breeding water in two urban areas of Cairo Governorate, Egypt. J entomol acarol res. 2013;45: e17. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surendran S, Ramasamy R. Some characteristics of the larval breeding sites of Anopheles culicifacies species B and E in Sri Lanka. J Vector Borne Dis. 2005;42: 39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao BB, Harikumar P, Jayakrishnan T, George B. Characteristics of Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus Skuse (Diptera: Culicidae) breeding sites. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2011;42: 1077–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costanzo KS, Mormann K, Juliano SA. Asymmetrical competition and patterns of abundance of Aedes albopictus and Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2005;42: 559–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufman MG, Walker ED. Indirect Effects of Soluble Nitrogen on Growth of Ochlerotatus triseriatus Larvae in Container Habitats. J Med Entomol. 2006;43: 677–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mercer DR, Sheeley SL, Brown EJ. Mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) development within microhabitats of an Iowa wetland. J Med Entomol. 2005;42: 685–93. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2005)042[0685:MDCDWM]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lund A, McMillan J, Kelly R, Jabbarzadeh S, Mead DG, et al. Long term impacts of combined sewer overflow remediation on water quality and population dynamics of Culex quinquefasciatus, the main urban West Nile virus vector in Atlanta, GA. Environmental research. 2014;129: 20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2013.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soleimani-Ahmadi M, Vatandoost H, Hanafi-Bojd AA, Zare M, Safari R, Mojahedi A, et al. Environmental characteristics of anopheline mosquito larval habitats in a malaria endemic area in Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2013;6: 510–5. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(13)60087-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikookar S, Fazeli-Dinan M, Azari-Hamidian S, Mousavinasab S, Arabi M, et al. Species composition and abundance of mosquito larvae in relation with their habitat characteristics in Mazandaran Province, northern Iran. Bulletin of Entomological Research. 2017; 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chirebvu E, Chimbari MJ. Characteristics of Anopheles arabiensis larval habitats in Tubu village, Botswana. J Vector Ecol. 2015;40: 129–38. doi: 10.1111/jvec.12141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yaghoobi-Ershadi M, Namazi J, Piazak N. Bionomics of Anopheles sacharovi in Ardebil province, northwestern Iran during a larval control program. Acta trop. 2001;78: 207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanafi-Bojd A, Vatandoost H, Oshaghi M, Charrahy Z, Haghdoost A, Sedaghat M, et al. Larval habitats and biodiversity of anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in a malarious area of southern Iran. J Vector Borne Dis. 2012;49: 91–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghanbari M, Rakhsh Khorshid A, Salehi M, Hassanzehi A. The study of physical and chemical factors affecting breeding places of Anopheles in Iranshahr. Tabib-e-Shargh, J Zahedan Univ Med Sci. 2005;7: 221–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abai MR, Saghafipour A, Ladonni H, Jesri N, Omidi S, Azari-Hamidian S. Physicochemical Characteristics of Larval Habitat Waters of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Qom Province, Central Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2016;10: 65–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naficy K, Saidi S. Serological survey on viral antibodies in Iran. Trop Geogr Med.1970;22: 183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bagheri M, Terenius O, Oshaghi MA, Motazakker M, Asgari S, et al. West Nile Virus in Mosquitoes of Iranian Wetlands. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015; 15: 750–754. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2015.1778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bashar K, Rahman MS, Nodi IJ, Howlader AJ. Species composition and habitat characterization of mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae in semi-urban areas of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Pathog Glob Health. 2016;110: 48–61. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2016.1179862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fager EW, McGowan JA. Zooplankton Species Groups in the North Pacific Co-occurrences of species can be used to derive groups whose members react similarly to water-mass types. Sci. 1963;140: 453–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silver JB. Mosquito ecology: field sampling methods: Springer; New York; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikookar SH, Moosa-Kazemi SH, Oshaghi MA, Vatandoost H, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Enayati AA, et al. Biodiversity of culicid mosquitoes in rural Neka township of Mazandaran province, northern Iran. J Vector Borne Dis. 2015;52: 63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mousson L, Dauga C, Garrigues T, Schaffner F, Vazeille M, Failloux A-B. Phylogeography of Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti (L.) and Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse)(Diptera: Culicidae) based on mitochondrial DNA variations. Genet Res. 2005;86: 1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0016672305007627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mesgari A, Pazokinegad E, Bakhshi F. Statistical Yearbook 2013 Mazandaran: Mazandaran Governor -Deputy Planning; 2013.

- 30.Shahgudian ER. A key to the anophelines of Iran. Acta Medica Iranica. 1960;3: 38–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azari-Hamidian S, Harbach RE. Keys to the adult females and fourth-instar larvae of the mosquitoes of Iran (Diptera: Culicidae). Zootaxa. 2009; 2078: 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rice EW, Bridgewater L, Association APH. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater: American Public Health Association; Washington, DC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurlbert SH. A Coefficient of Interspecific Assciation. Ecology. 1969; 50: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okogun GR, Nwoke BE, Okere AN, Anosike JC, Esekhegbe AC. Epidemiological implications of preferences of breeding sites of mosquito species in Midwestern Nigeria. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2003;10: 217–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nikookar SH, Azari-Hamidian S, Fazeli-Dinan M, Nasab SNM, Aarabi M, Ziapour SP, et al. Species composition, co-occurrence, association and affinity indices of mosquito larvae (Diptera: Culicidae) in Mazandaran Province, northern Iran. Acta trop. 2016; 157:20–9. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikookar SH, Moosa-Kazemi SH, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Vatandoost H, Oshaghi MA, Ataei A, et al. Fauna and Larval Habitat Characteristics of Mosquitoes in Neka County, Northern Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2015;9: 253–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikookar SH, Moosa-Kazemi SH, Oshaghi M, Yaghoobi-Ershadi M, Vatandoost H, Kianinasab A. Species composition and diversity of mosquitoes in neka county, mazandaran province, northern iran. Iran J Arthropod Borne Dis 2010;4: 26–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaim M. The distribution and larval habitat characteristics of Iranian Culicinae. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1987;3: 568–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vinogradova EB. Culex pipiens pipiens mosquitoes: taxonomy, distribution, ecology, physiology, genetic, applied importance and control: Pensoft, SoÞa, Bulgaria; 2000.

- 40.Dehghan H, Sadraei J, Moosa-Kazemi S. The morphological variations of Culex pipiens larvae (Diptera: Culicidae) in Yazd Province, central Iran. Iran J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2010;4: 42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischer S, Schweigmann N. (2004) Culex mosquitoes in temporary urban rain pools: Seasonal dynamics and relation to environmental variables. J Vector Ecol.2004;29: 365–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Service M. Agricultural development and arthropod-borne diseases: a review. Revista de saúde pública. 1991;25: 165–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norris DE. Mosquito-borne diseases as a consequence of land use change. EcoHealth. 2004;1: 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghavami MB, Ladoni H. Mosquito fauna and abundance (Diptera:Culicidae) in Zanjan province. J Zanjan Univ Med Sci. 2005;13: 46–54 [Persian with English abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abai MR, Azari-Hamidian S, Ladonni H, Hakimi M, Mashhadi-Esmail K, Sheikhzadeh K, et al. Fauna and checklist of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) of East Azerbaijan Province, northwestern Iran. Iran J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2007;1: 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Azari-Hamidian S, Yaghobi-Ershadi M, Javadian E, Abai M, Mobedi I, Linton YM, et al. Distribution and ecology of mosquitoes in a focus of dirofilariasis in northwestern Iran, with the first finding of filarial larvae in naturally infected local mosquitoes. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23: 111–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azari-Hamidian S. Larval habitat characteristics of the genus Anopheles (Diptera: culicidae) and a checklist of mosquitoes in guilan province, northern iran. Iran J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2011;5: 37–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Juliano SA. Species interactions among larval mosquitoes: context dependence across habitat gradients. Annu Rev Entomol. 2009;54: 37 doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.54.110807.090611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ladonni H, Azari-Hamidian S, Alizadeh M, Abai MR, Bakhshi H. The fauna, habitats, and affinity indices of mosquito larvae (Diptera: Culicidae) in Central Iran. N West J Zool. 2015;11 76–85. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kibuthu TW, Njenga SM, Mbugua AK, Muturi EJ. Agricultural chemicals: life changer for mosquito vectors in agricultural landscapes? Parasit Vectors. 2016; 9: 500 doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1788-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noori N, Lockaby BG, Kalin L. Larval development of Culex quinquefasciatus in water with low to moderate. J Vector Ecol. 2015;40: 208–220. doi: 10.1111/jvec.12156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Armistead JS, Nishimura N, Arias JR, Lounibos LP. Community ecology of container mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Virginia following invasion by Aedes japonicus. J Med Entomol. 2012;49: 1318–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Butlin K, Adams ME, Thomas M. Sulphate-reducing bacteria and internal corrosion of ferrous pipes conveying water. Nature. 1949;163: 26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gopalakrishnan R, Das M, Baruah I, Veer V, Dutta P. Physicochemical characteristics of habitats in relation to the density of container-breeding mosquitoes in Asom, India. J Vector Borne Dis. 2013;50: 215–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sallam MF, Al Ahmed AM, Abdel-Dayem MS, Abdullah MA. (2013) Ecological niche modeling and land cover risk areas for rift valley fever vector, culex tritaeniorhynchus giles in Jazan, Saudi Arabia. PLoS One. 2015;8: e65786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reusken C, De Vries A, Ceelen E, Beeuwkes J, Scholte EJ. A study of the circulation of West Nile virus, Sindbis virus, Batai virus and Usutu virus in mosquitoes in a potential high-risk area for arbovirus circulation in the Netherlands,“De Oostvaardersplassen.”. Eur Mosq Bull. 2011; 29: 66–81. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fonseca DM, Keyghobadi N, Malcolm CA, Mehmet C, Schaffner F, et al. Emerging vectors in the Culex pipiens complex. sci. 2004;303: 1535–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayes EB, Komar N, Nasci RS, Montgomery SP, O'Leary DR, et al. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005; 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Figueroa DP, Scott S, Gonzalez CR, Veloso C, Canals M (2016) Assessing the larval niche of Culex pipiens in Chile. Int J Mosq Res. 2016;3: 11–6. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.