Significance

A common variant of histidine-rich Ca-binding protein (HRC), where an alanine replaces a serine at amino acid 96, can increase the risk of dying from severe heart disease. Using human, mice, and cellular models, we show that this variant blocks position 96 from becoming phosphorylated, a prevalent type of protein modification carried out by kinase enzymes. We demonstrate that phosphorylation of HRC at Ser96 indeed provides protection from heart disease, and we identify family with sequence similarity 20C (Fam20C) as the kinase that phosphorylates HRC. HRC phosphorylation appears to play a role in regulating Ca cycling that is critical for proper cardiac muscle contraction. This demonstration of Fam20C’s role in heart disease opens up avenues for potential preventative or therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: histidine-rich calcium-binding protein, Fam20C kinase, heart, arrhythmia, phosphorylation

Abstract

Precise Ca cycling through the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), a Ca storage organelle, is critical for proper cardiac muscle function. This cycling initially involves SR release of Ca via the ryanodine receptor, which is regulated by its interacting proteins junctin and triadin. The sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca ATPase (SERCA) pump then refills SR Ca stores. Histidine-rich Ca-binding protein (HRC) resides in the lumen of the SR, where it contributes to the regulation of Ca cycling by protecting stressed or failing hearts. The common Ser96Ala human genetic variant of HRC strongly correlates with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. However, the underlying molecular pathways of this disease remain undefined. Here, we demonstrate that family with sequence similarity 20C (Fam20C), a recently characterized protein kinase in the secretory pathway, phosphorylates HRC on Ser96. HRC Ser96 phosphorylation was confirmed in cells and human hearts. Furthermore, a Ser96Asp HRC variant, which mimics constitutive phosphorylation of Ser96, diminished delayed aftercontractions in HRC null cardiac myocytes. This HRC phosphomimetic variant was also able to rescue the aftercontractions elicited by the Ser96Ala variant, demonstrating that phosphorylation of Ser96 is critical for the cardioprotective function of HRC. Phosphorylation of HRC on Ser96 regulated the interactions of HRC with both triadin and SERCA2a, suggesting a unique mechanism for regulation of SR Ca homeostasis. This demonstration of the role of Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation in heart disease will open new avenues for potential therapeutic approaches against arrhythmias.

Dilated cardiomyopathy is a disease of the heart muscle resulting from a diverse array of conditions that damage the heart and impair myocardial function (1). Although therapeutic advances have improved survival, these patients still exhibit high mortality, associated with sudden death in over 50% of the cases (2). Reduced contractile function and pathological remodeling are clinical hallmarks of heart failure and ventricular arrhythmogenesis, but the early events that impair the performance of the cardiomyocytes are largely undefined.

Intracellular Ca handling is the central coordinator of cardiac contraction and relaxation. Contraction begins with sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) release of Ca into the cytosol via the ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2); relaxation occurs with SR Ca uptake via the SR/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca ATPase (SERCA2a) pump (3). Other proteins also contribute to this process, including triadin and junctin, which regulate RYR2, and phospholamban, which regulates SERCA2a (4, 5). In the past decade, the histidine-rich Ca-binding protein (HRC) has been suggested to be an additional component of the SR Ca handling machinery (6). HRC is a regulator of both SERCA2a, through its direct binding interaction, and RyR2 function, through its binding to triadin. HRC therefore mediates SR Ca storage, uptake, and release (6).

Consistent with the role of HRC in Ca handling, acute or transgenic HRC overexpression in cardiomyocytes results in a delayed cytoplasmic Ca decline and depressed cardiomyocyte SR Ca uptake, which progress to cardiac hypertrophy upon aging (7). Conversely, ablation of HRC results in significantly enhanced contractility, Ca transients, and maximal SR Ca uptake rates. However, HRC-deficient cardiomyocytes develop aftercontractions at a significantly higher frequency, compared with wild-type (WT) cells under stress conditions (8). Interestingly, HRC protein levels are reduced both in animal models of heart failure and in failing human hearts (9). These findings indicate that HRC plays a key role in the regulation of Ca homeostasis in cardiac excitation/contraction coupling.

The importance of HRC in cardiomyocyte Ca cycling is highlighted by the identification of a common human genetic variant [Ser96Ala (S96A)] that has been linked in a dosage-dependent manner to life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Specifically, dilated cardiomyopathy patients harboring the Ala/Ala variant had a fourfold increased risk of death compared with those with the Ser/Ser variant (10). Genetic analysis indicates that roughly 60% of people have at least one copy of S96A, suggesting that this condition has extremely broad implications (10). Animal studies indicate that the substitution of Ala in position 96 of HRC alters its regulatory effects, resulting in overall disturbed SR Ca homeostasis, as evidenced by reduced Ca transient amplitude and prolongation of Ca decay time (11). Importantly, these Ca abnormalities elicited by S96A-HRC were associated with aberrant SR Ca release and arrhythmogenesis, consistent with the phenotype of human carriers.

While the HRC S96A genetic variant is linked to ventricular arrhythmias as noted above, the molecular mechanism underlying this chronic heart disease is unknown. It is intriguing that Ser96 occurs within a Ser-X-Glu (S-x-E) motif, where X can be any amino acid, and this constitutes the known consensus motif for Ser phosphorylation by the secretory pathway kinase, family with sequence similarity 20C (Fam20C) (12–14). Thus, Ser96 in HRC could be phosphorylated by Fam20C, and the S96A polymorphism would abrogate this phosphorylation. Importantly, Fam20C has a signal sequence that targets it to the ER/SR lumen (12). This puts Fam20C within the necessary subcellular compartment to interact with luminal substrates, such as HRC, in contrast to the overwhelming majority of known protein kinases, which are predominantly localized in the cytoplasm or nucleus (15).

MS studies have detected HRC phosphorylation on Ser96 (16, 17). Given that Fam20C is the only kinase in the secretory pathway that has been shown to phosphorylate S-x-E motifs (13), we hypothesize that Fam20C phosphorylates HRC on Ser96 in the SR of cardiac cells and that this phosphorylation protects dilated cardiomyopathy patients from life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias.

Results

HRC Is Phosphorylated on Ser96 in the Human Heart.

To detect the phosphorylation status of endogenous HRC in human heart tissue, HRC was immunoprecipitated from whole-cardiac homogenates, and the phosphorylation sites were mapped by MS. Notably, endogenous HRC was phosphorylated on Ser96 (Fig. 1 A and B and Fig. S1). In total, there were 10 phosphorylation sites observed in HRC, all on Ser residues (Fig. 1A). The majority of these phosphorylated Ser (pSer) residues fall within the S-x-E consensus motif for the secretory pathway kinase Fam20C, including HRC pSer96, which is highly conserved among mammals (Fig. 1C). Treatment of the immunoprecipitated human HRC with λ-phosphatase resulted in an increase in electrophoretic mobility, demonstrating robust endogenous HRC phosphorylation (Fig. 1D). These data show that HRC is phosphorylated in vivo and Ser96 is a relevant phosphorylation site in human hearts.

Fig. 1.

HRC is phosphorylated on Ser96 in human hearts. (A) Schematic depicting HRC domain architecture and phosphorylation sites. Endogenous HRC was immunoprecipitated from human heart extracts and analyzed by phosphoproteomics using liquid chromatography tandem MS. (B) Phosphopeptide derived from MS chromatogram showing human HRC Ser96 phosphorylation (S+80) in vivo. (C) Residues corresponding to the Fam20C S-x-E phosphorylation motif of HRC are highlighted in blue. Numbers represent the first amino acid number in the motif. Accession numbers are as follows: human (Homo sapiens): ACH88003, mouse (Mus musculus): AAD42061, rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus): AAA31279, rat (Rattus norvegicus): AAP31904, cow (Bos taurus): NP_001095783, orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus): CAH89847, dog (Canis lupus familiaris): F6UPH0, and pig (Sus scrofa): XP_013854077. (D) Endogenous human HRC immunoprecipitates were treated with λ-phosphatase (λ-phos). Phosphorylated HRC (pHRC) and unphosphorylated HRC are denoted by the arrows and show that λ-phos results in dephosphorylation of HRC.

Fig. S1.

MS chromatogram depicting the phosphopeptide showing human HRC Ser96 phosphorylation (S+80) in vivo.

Fam20C Phosphorylates HRC on Ser96.

Because HRC resides in the lumen of the SR and contains several pSer residues within S-x-E sites, we sought to determine if HRC was a substrate of Fam20C in the SR of cardiac myocytes. First, we investigated the interaction between HRC and Fam20C in mouse hearts expressing human Ser96-HRC. We used a model that we previously developed with human HRC (Ser96-HRC) expressed in a murine Hrc null background, where the human HRC expression is similar to WT murine HRC expression (11). Both HRC and Fam20C were immunoprecipitated from cardiac homogenates and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting with antibodies to HRC and Fam20C. The results revealed that HRC and Fam20C were present in a stable complex that could be coimmunoprecipitated (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Fam20C is the kinase that phosphorylates HRC. (A) Protein immunoblot of HRC and Fam20C immunoprecipitates (IPs) from cardiac homogenates (1 mg of total protein) from Ser96-HRC mouse hearts showing an association between HRC and Fam20C. The IPs were resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies recognizing Fam20C (Top) and HRC (Bottom). IPs with anti-IgG plus agarose were used as negative controls. HRC-1 and HRC-2 represent IPs from different hearts. (B, Top) FLAG immunoblot of Flag IPs from cell lysates from H9C2 cells coexpressing HRC-FLAG with either WT or the catalytically inactive HA-DA. (B, Bottom) HA immunoblot. The λ-phosphatase (λ-phos) treatment was only applied to HRC-FLAG IPs. Phosphorylated HRC (pHRC) and unphosphorylated HRC are denoted by the arrows and show that λ-phos results in dephosphorylation of HRC. (C, Top) FLAG immunoblot of Flag-IPs from Fam20C KO and WT U20S cells overexpressing HRC-FLAG showing phosphorylation of HRC in WT cells. (C, Bottom) Fam20C immunoblot of conditioned media. (D, Top) Autoradiograph depicting time-dependent incorporation of 32P from [γ-32P]ATP into HRC using purified proteins. HRC-FLAG (transiently expressed and purified from Fam20C KO U20S cells) was incubated with WT or D478A (inactive) recombinant Fam20C (DA; purified from baculovirus) in an in vitro kinase assay. (D, Bottom) Parallel anti-FLAG immunoblot.

To establish that Fam20C can phosphorylate HRC within the lumen of the secretory pathway, HRC with a C-terminal epitope tag (HRC-FLAG) was coexpressed in H9C2 rat cardiomyoblast cells with an HA epitope-tagged WT Fam20C or a catalytically inactive Asp478Ala (D478A) mutant of Fam20C (12). HRC and Fam20C were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and analyzed by Western blotting. In the presence of the D478A mutant, HRC-FLAG migrated as a single band, whereas coexpression with WT Fam20C-HA resulted in the presence of an additional HRC band with diminished electrophoretic mobility, indicative of phosphorylation (Fig. 2B). Treatment with λ-phosphatase demonstrated that this shift in mobility was indeed due to phosphorylation. WT Fam20C also had a diminished electrophoretic mobility relative to Fam20C- D478A (DA), suggesting that it was phosphorylated, as previously demonstrated (12). To determine if Fam20C was the predominant HRC kinase, we expressed HRC-FLAG in WT U2OS cells and in U2OS cells with Fam20C knocked out, using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing (18). HRC was robustly phosphorylated in the presence of endogenous Fam20C but was not phosphorylated in the Fam20C KO cells, indicating that Fam20C is the HRC kinase (Fig. 2C).

To confirm that HRC is a direct substrate for Fam20C, HRC-FLAG was expressed in U2OS cells that were deficient in Fam20C, purified by Flag immunoprecipitation, and used as a substrate for Fam20C in an in vitro kinase assay. Recombinant Fam20C phosphorylated HRC in a time-dependent manner, as observed by the increasing 32P signal (Fig. 2D). Accordingly, HRC was not modified by the catalytically inactive DA mutant protein.

Because HRC was phosphorylated by Fam20C both in vitro and in vivo, we sought to determine the positions of the phosphorylation sites. HRC-FLAG was expressed in Fam20C KO and WT U2OS cells (as in Fig. 2C) and was purified by immunoprecipitation from cell lysates, and the phosphorylation sites were mapped by MS. We identified 13 pSer sites on HRC from cells expressing endogenous WT Fam20C, including pSer96 (Fig. 3 and Fig. S2). The majority of the Fam20C-dependent phosphorylation sites identified were also detected in the MS phosphoproteomic analysis of human hearts (Fig. 1A), and, again, most of the pSer residues fall within S-x-E consensus sites (Fig. 3A). Notably, no phosphorylated peptides were identified on HRC purified from Fam20C KO cells. Taken together, our results demonstrate that Fam20C extensively phosphorylates HRC, including the critical Ser96 residue. Because the absence of this phosphorylated site is associated with arrhythmias, we hypothesize that Ser96 phosphorylation plays an important regulatory role in Ca handling.

Fig. 3.

HRC is phosphorylated on Ser96 by Fam20C in cells. (A) Schematic depicting domain architecture and Fam20C-dependent phosphosites. HRC-FLAG was expressed in Fam20C KO and WT U2OS cells and was FLAG-immunoprecipitated, and the phosphorylation sites were mapped by comparative tandem MS (MS/MS). (B) Phosphopeptide derived from MS chromatogram showing Ser96-HRC phosphorylation (S+80) in cells.

Fig. S2.

MS chromatogram depicting the phosphopeptide showing HRC Ser96 phosphorylation (S+80) from cells.

Mimicking Phosphorylation of HRC Ser96 Diminishes Aftercontractions in Cardiomyocytes.

We previously demonstrated that S96A-HRC and Hrc null (HRC KO) mouse cardiomyocytes increased arrhythmogenic features under stress in comparison to Ser96-HRC cardiomyocytes (8, 11). The S96A-HRC cells also displayed hyperactive RyR2 activity that resulted in aftercontractions (11). Therefore, to further elucidate the role and functional significance of Ser96 phosphorylation, this site was mutated to an Asp (S96D) in an adenoviral expression construct to generate an HRC mutant that would mimic constitutive phosphorylation of Ser96. Isolated adult HRC KO mouse cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviruses to express S96D-HRC, S96A-HRC, or a GFP control. We then examined the extent of aftercontractions in the cardiomyocytes subjected to 2-Hz electrical field stimulation in the absence and presence of stress conditions elicited by 1 μM isoproterenol.

The results revealed that in the absence of isoproterenol, spontaneous aftercontractions were significantly decreased to 11% in cells expressing HRC S96D, compared with 34% in cells expressing HRC S96A or 15% in cells expressing GFP. Furthermore, isoproterenol inclusion resulted in spontaneous aftercontractions in only 19% of HRC S96D-expressing cells, compared with 32% in GFP- and 64% in HRC S96A-expressing cells (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

HRC phosphomimetic decreases aftercontractions in cardiomyocytes. (A) Aftercontractions in HRC KO mouse cardiomyocytes infected with adenoviruses to express GFP, S96D-HRC, or S96A-HRC under field stimulation of 2 Hz and in the absence or presence of 1 μM isoproterenol. Data are mean ± SEM of the total number of cells per group (n = 22–45 cells from three hearts per group). Comparisons were performed using a t test (*P < 0.05 in comparison to S96D-HRC) and show that S96D-HRC exhibits reduced aftercontractions in either the absence or presence of isoproterenol. (B) Cardiomyocytes were isolated from mutant S96A-HRC mouse hearts and infected as above, and aftercontractions were measured using ±1 μM isoproterenol with field stimulation at 2 Hz (n = 18–37 cells for three S96A hearts). Data are mean ± SEM of the total number of cells per group. Comparisons were performed using a t test (*P < 0.05 in comparison to S96D-HRC), showing that S96D diminishes the aftercontractions in S96A cardiomyocytes.

We have previously shown that the human HRC S96A genetic variant is correlated with ventricular arrhythmia and sudden death in dilated cardiomyopathy, and expression of this variant in the null mouse background is also arrhythmogenic (11). Thus, we speculated that constitutive phosphorylation of HRC could directly compete with and rescue the phenotype of the S96A-HRC cardiomyocytes and potentially have beneficial effects. Indeed, adenovirus-mediated expression of S96D-HRC in cardiomyocytes isolated from S96A-HRC mice diminished aftercontractions to 9% of cells, compared with 38% of those expressing GFP in the absence of isoproterenol (Fig. 4B). Similarly, the S96A-HRC cardiomyocytes expressing S96D-HRC developed significantly less (16%) spontaneous aftercontractions compared with cells expressing GFP (64%) in the presence of isoproterenol (Fig. 4B). Thus, similar to our findings with HRC KO cardiomyocytes, expression of S96D-HRC diminished aftercontractions in S96A-HRC arrhythmogenic cardiomyocytes, suggesting an important role for Ser96 phosphorylation in the heart under stress conditions.

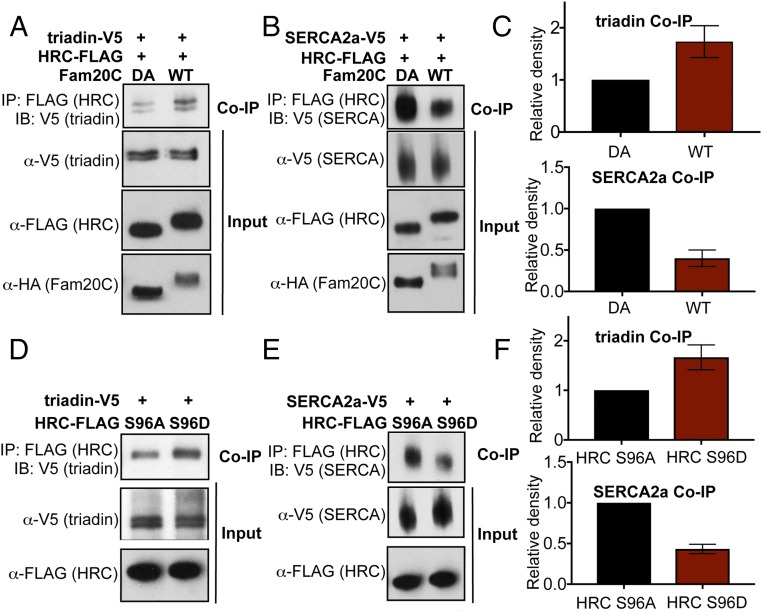

Phosphorylation of HRC Regulates Its Interactions with Triadin and SERCA2a.

HRC has been demonstrated to bind to both triadin and SERCA2a, and the binding to each partner is altered when Ser96 is mutated to Ala (11, 19). Because we show here that Ser96 is phosphorylated by Fam20C (Fig. 2), we hypothesized that Ser96 phosphorylation could modulate the interaction of HRC with triadin and SERCA2a. To test this, we cotransfected H9C2 rat cardiomyoblast cells with constructs encoding HRC-FLAG and each binding partner (either triadin or SERCA2a with C-terminal V5 epitope tags). These cells were also cotransfected to express either WT or catalytically inactive HA-DA, followed by immunoprecipitation and analysis by Western blotting (Fig. 5 A and B). We observed a twofold increase in the amount of triadin-V5 coimmunoprecipitated with phosphorylated HRC-FLAG (Fig. 5 A and C). In contrast, we found that roughly threefold more SERCA2a was coimmunoprecipitated with unphosphorylated HRC (Fig. 5 B and C). This is in agreement with previous results, which showed that HRC S96A displayed diminished interactions with triadin in cardiomyocytes but an increase in binding with SERCA2a (11, 19). Furthermore, we demonstrated that the S96D-HRC phosphomimetic displayed increased binding to triadin and diminished binding to SERCA2a, compared with S96A-HRC in H9C2 cells (Fig. 5 D–F), confirming that the phosphomimetic mechanistically replicates phosphorylation. Taken together, the data suggest that unphosphorylated HRC acts similar to the human mutant, HRC S96A (Fig. 6). Therefore, phosphorylation of HRC regulates its interactions with these proteins that are critical for SR Ca homeostasis.

Fig. 5.

Phosphorylation of HRC regulates its interactions with triadin and SERCA2a. (A) Immunoblot (IB) analysis of HRC-FLAG coexpressed with triadin-V5 and either Fam20C WT or the catalytically inactive DA mutant in H9C2 cells. HRC was Flag-immunoprecipitated from whole-cell lysates, and triadin coimmunoprecipitation was assayed via V5 immunoblotting. The two lower immunoblot panels represent controls for expression levels following immunoprecipitation (IP) of the corresponding epitope. (B) HRC-FLAG coexpressed with SERCA2a-V5 and either Fam20C WT or the catalytically inactive DA mutant. HRC was Flag-immunoprecipitated, and SERCA2a coimmunoprecipitation was assayed via V5 immunoblotting. (C) Results from A and B are expressed as the relative densitometry of V5 IBs of either triadin or SERCA2a in DA samples (n = 3), and show increased binding to triadin but reduced binding to SERCA2a by phosphorylated (WT) HRC. (D) IB analysis of Flag-HRC-S96A or FLAG-HRC-S96D coexpressed with triadin-V5 in H9C2 cells. (Top) HRC was Flag-immunoprecipitated from whole-cell lysates, and triadin co-IP was assayed via V5 immunoblotting. (Middle and Bottom) Immunoblot panels represent controls for expression levels following IP of the corresponding epitope. (E) Either Flag-HRC-S96A or FLAG-HRC-S96D coexpressed with SERCA2a-V5. HRC was Flag-immunoprecipitated, and SERCA2a co-IP was assayed via V5 immunoblotting. (F) Results from A and B are expressed as relative densitometry of V5 IBs of either triadin or SERCA2a (n = 3), and show increased binding to triadin but reduced binding to SERCA2a by the phosphomimetic HRC S96D.

Fig. 6.

Model proposing how Fam20C-mediated phosphorylation of HRC Ser96 affects cardiac Ca homeostasis. The pSer96-HRC binds tighter to triadin than S96A-HRC, which cannot be phosphorylated. Conversely, S96A-HRC or unphosphorylated Ser96-HRC binds tighter to SERCA2a. This suggests that Ser96-HRC phosphorylation (P) regulates HRC’s interactions with the major SR Ca-cycling proteins. Therefore, HRC Ser96 phosphorylation is important for SR Ca homeostasis, preventing arrhythmias.

Discussion

This study presents evidence that the human S96A polymorphism in HRC abrogates a phosphorylation site by Fam20C. The absence of this phosphorylation site is associated with malignant ventricular arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death in dilated cardiomyopathy carriers. Previous studies reported the presence of various genetic variants in HRC. These include Leu35Leu, Ser43Asn, Ser96Ala, Glu202_Glu203insGlu, and Asp261del, as well as a 51-aa insertion at codon 321 (10). Each genetic variant exhibited similar frequency in controls and dilated cardiomyopathy patients, where at least one allele of each variant appeared in ∼60% of the patients (10). However, only the S96A-HRC polymorphism appeared to significantly correlate with ventricular arrhythmias in dilated cardiomyopathy patients. The functional significance of this variant was elucidated by the generation and characterization of mouse models expressing the human Ser96 or S96A variant in the Hrc null hearts. The single-nucleotide substitution of T286G in HRC, resulting in the naturally occurring Ala96 variant, leads not only to depressed SR Ca cycling and contractility but also to increased SR Ca leak during diastole, as well as SERCA2a inhibition (11). The induced diastolic leak by hyperactive RyR2 triggered aftercontractions and delayed afterdepolarizations in cardiomyocytes, resulting in ventricular arrhythmogenesis.

Both HRC and the protein kinase Fam20C reside in the lumen of the SR, where Fam20C likely phosphorylates HRC before Fam20C’s secretion (13). We note that although HRC has been reported to be a substrate in vitro for several kinases, including casein kinase II (20), these phosphorylations have limited functional significance because HRC is in the lumen of the SR, while casein kinase II is in the nucleus and cytoplasm (21).

We sought to determine if Fam20C played a role in HRC’s pathophysiology. We provide several lines of evidence demonstrating that HRC is phosphorylated on Ser96 and that Fam20C is the responsible kinase. Fam20C coimmunoprecipitated with HRC in cardiac myocytes, showing endogenous cardiac Fam20C directly interacts with HRC (Fig. 2A). Both a cell-based assay and an in vitro kinase assay with Fam20C and HRC showed high levels of HRC phosphorylation (Fig. 2 B–D). In cells, several Ser residues within S-x-E sites, including Ser96 in HRC, were identified by MS as phosphorylated in WT but not in Fam20C-deficient cells (Fig. 3). Finally, Ser96-HRC was phosphorylated in human heart postmortem samples (Fig. 1 A and B). Notably, no peptides were identified with unphosphorylated Ser96 via MS, suggesting a high stoichiometry of phosphorylation at Ser96 in human specimens. Interestingly, the HRC pig sequence lacks a Glu residue at position +2 downstream of Ser96 (Fig. 1C), suggesting it would not be phosphorylated by Fam20C, which may be a contributing factor to the high propensity for arrhythmias in this species under stress conditions (22).

The physiological consequences of HRC Ser96 phosphorylation were elucidated through mutation of Ser96 to Asp (S96D), generating a phosphomimetic motif in this position. This strategy allowed direct probing of the effects of Ser96-HRC phosphorylation. This is important because Fam20C can phosphorylate other serine residues on HRC and Fam20C phosphorylation of other SR luminal proteins may also affect SR Ca handling. We demonstrate that S96D-HRC rescues the arrhythmogenic effects elicited by S96A-HRC or HRC ablation in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4). This demonstrates a critical physiological role of Ser96-HRC phosphorylation in cardiomyocyte Ca handling.

The mechanisms underlying the protective effects of phosphorylated HRC in SR Ca cycling appear to include its enhanced binding (approximately twofold) to triadin, but diminished (approximately threefold) binding to SERCA2a (Fig. 5). In agreement, S96A-HRC’s decreased binding to triadin (11) and increased binding to SERCA2a (19) demonstrate that S96A-HRC functions similar to unphosphorylated HRC. Taken together, this suggests that HRC phosphorylation at Ser96 promotes triadin binding and may control Ca leak through RyR2, while it inhibits SERCA2a binding and may enhance SR Ca transport (Fig. 6). We note that HRC is also known to bind SR Ca; however, in prior reports, S96A-HRC showed similar Ca-binding properties to Ser96-HRC (11). Therefore, it is likely that the primary function of Fam20C-mediated phosphorylation of Ser96 on HRC is to modulate its interactions with triadin and SERCA2a, and that S96A-HRC is consequential because the phosphorylation site is removed.

Here, we describe a physiological function of Fam20C phosphorylation. The original identification of Fam20C solved the long-standing conundrum of which kinase is responsible for phosphorylating the milk protein casein, along with other secreted phosphoproteins involved in bone and teeth formation (14). Lethal mutations in Fam20C in humans result in the development of Raine syndrome, a neonatal osteosclerotic bone dysplasia that frequently involves ectopic calcification (12, 23), whereas nonlethal mutations have been linked to hypophosphatemic rickets and amelogenesis imperfecta, a developmental tooth disease (24, 25).

The biochemical and physiological consequences of substrate phosphorylation by Fam20C have been demonstrated in some cases. For instance, Fam20C phosphorylation of FGF23 impacts the cellular processing of FGF23, and loss of Fam20C activity results in hypophosphatemic rickets (18, 25). In addition, the Ser216Leu mutation in enamelin results in amelogenesis imperfecta (24, 26); in this case, the Ser is mutated within the S-x-E motif, blocking Fam20C phosphorylation, similar to S96A-HRC. Another example is a missense mutation of Ser91 in BMP4 that leads to renal hypodysplasia (13, 27). While a clear link between Fam20C and biomineralization has been established, newer results suggest that Fam20C has broader biological roles, including wound healing, regulation of the extracellular matrix, and adhesion and migration of cancer cells (13). Given that Fam20C phosphorylation has only been explored in limited contexts to date, it appears that the breadth of Fam20C’s impact is only starting to be unraveled. In particular, our work here shows that it has a previously unidentified role in cardiac function, which likely extends beyond HRC phosphorylation to include other SR phosphoproteins.

In summary, our findings indicate that phosphorylation of HRC on Ser96 by Fam20C protects against cardiac arrhythmias. Given the prevalence of dilated cardiomyopathy and the likely high occurrence of the HRC S96A polymorphism, our results provide a mechanistic understanding of a devastating heart condition. Furthermore, this establishes a link between Fam20C and SR Ca handling, identifying Fam20C as a potential target for heart disease treatments.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Transgenic Mice Expressing Human HRC.

Generation of the S96-HRC and A96-HRC mouse models expressing the cardiac-specific human HRC cDNA with the HRC Ser96 or HRC Ala96 mutation and transferring to HRC KO background has been described previously (11). The handling and maintenance of animals were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Cincinnati. Eight- to 12-week-old mice were used for all studies. The investigation conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (28) of the NIH.

Mammalian Cell Culture and Transfection.

U2OS WT and Fam20C KO cells, along with H9C2 rat cardiomyoblast cells, were cultured in DMEM (Life Technology) supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 μg/mL penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO) as previously described (18). Transient transfection was carried out using Fugene6 (Promega) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Adult Mouse Cardiomyocyte Isolation and Culture.

Adult mouse cardiomyocytes were isolated by liberase enzyme digestion as previously described (11). Freshly isolated myocytes were plated on laminin-coated (10 μg/mL) dishes for 2 h at 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C. After 2 h of attachment, cardiac myocytes were transduced with adenoviruses to express S96D-HRC, S96A-HRC, or GFP at a multiplicity of infection of 500 in 1 mL of 10 μM blebbistatin (Toronto Research Chemicals) and culture media as described previously (19). Experiments were performed 24 h after infection.

Aftercontraction Measurements.

Infected cultured adult mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes were bathed in Krebs–Henseleit buffer [118 mM NaCl, 24.8 mM NaHCO3, 4.75 mM KCl, 1.18 mM MgSO4, 1.18 mM K3PO4, 1.8 mM CaCl2, and 11 mM glucose (pH 7.4)] at room temperature. To induce and measure aftercontractions, rod-shaped ventricular myocytes, which exhibited no spontaneous activity at rest, were paced at 2 Hz in the presence of 1 μM isoproterenol. After two or three trains of stimulation, pacing was stopped to allow the recording of spontaneous aftercontractions within 2–5 s. Data were collected using PCLAMP9 software through an Axon Digidata 1322A data acquisition system.

Biochemical Analysis.

Details on protein expression and purification, MS, in vitro phosphorylation assays, protein preparation from tissue specimens, recombinant adenoviral constructs, and immunoprecipitation and quantitative immunoblotting are presented in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

MS.

In preparation for high-resolution MS, immunoprecipitated recombinant HRC was treated with DTT to reduce disulfides and alkylated with iodoacetamide as previously described (29). Reduced/alkylated HRC was then precipitated by the use of methanol/chloroform treatment. Precipitated HRC was resuspended in 1 M urea and 50 mM Hepes (pH 8.5) for proteolytic digestion. Digestion of HRC was performed by trypsinolysis for 6 h at 37 °C. Digestion was quenched by adding TFA, and peptides were desalted with C18 solid-phase extraction columns as previously described (30). To identify HRC-related peptides, MS experiments were performed on an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer with an in-line Easy-nLC 1000 system and a chilled autosampler. Samples were introduced into the Easy-nLC 1000 system and eluted with a linear gradient from 10 to 60% of acetonitrile in 0.125% formic acid over 80 min at a flow rate of 300 nL⋅min−1. Electrospray ionization was achieved by applying 2,000 V at the inlet of the column heated to 60 °C. The mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode, with a survey scan performed over an m/z range of 500–1,200 at a resolution of 120,000 in the Orbitrap. Data were processed using the ProteomeDiscoverer 2.1 software package (ThermoFisher). Sequest-HT was used to assign identities to MS2 spectra searching against the UniProt human protein database. The database was appended to include a decoy database composed of all protein sequences in reversed order for downstream false discovery estimation (31). Data were filtered to a peptide and protein false discovery rate of less than 1% using the target-decoy search strategy (31).

In Vitro Phosphorylation Assays.

For the in vitro kinase assay with HRC-Flag purified from Fam20C KO U2OS cells and Fam20C from insect cells, the proteins were incubated in 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM [γ-32P]ATP (specific activity = 100–500 cpm/pmol), 0.25 mg/mL HRC, and 10 μg/mL Fam20C at 30 °C (12). Reactions were terminated at the indicated time points by SDS loading buffer, 15 mM EDTA, and boiling. Reaction products were separated by SDS/PAGE, and incorporated radioactivity was visualized via autoradiography and immunoblotting.

Protein Expression and Purification.

MBP-tagged Fam20C protein was expressed in Hi-5 insect cells and was purified as described previously (32). Briefly, Human Fam20C (69–584)-verified cDNA was cloned into the pI-secSUMOstar vector, which was modified to replace the SUMO tag with an MBP tag and a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease site. The MBP tag was removed via gel filtration chromatography following TEV protease cleavage.

Human HRC was cloned into a pCCF vector with a C-terminal Flag tag, and was expressed in Fam20C KO U2OS cells (18). Recombinant HRC was immunoprecipitated via Flag (M2) antibody (Sigma) and purified via the manufacturer’s recommendation.

The cDNAs for human SERCA2a and triadin were purchased from DNASU and were cloned into pCDNA4 with a C-terminal V5-tag. Human Fam20C (WT and/or DA) was cloned into pCDNA3 with a C-terminal HA-tag.

Protein Preparation from Tissue Specimens.

Cardiac homogenates from postmortem human specimens were prepared in ice-cold lysis buffer [10 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.2), 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaN3, 120 mM NaCl, and 1% Nonidet P-40] and zirconium beads using a MiniLys (Bertin) 3D bead-beating system. The Qubit Protein Assay Kit (Invitrogen Corp.) was used to determine protein concentration on a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen Corp.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The homogenates were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of the University of Cincinnati and conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (33).

Recombinant Adenoviral Constructs.

Adenoviruses were generated as previously described (19). Briefly, Human HRC cDNA expressing HRC S96D was generated using a Quik-Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis II Kit (Stratagene). The HRC cDNA harboring S96D mutant was cloned into the pShuttle vector and then transferred into the adeno-X viral DNA using the Ad-Easy XL System (Stratagene). Adenoviruses containing the cDNA sequence of mutant HRC (Ad.HRC-S96D) or green fluorescent protein (Ad.GFP) were assembled and amplified in HEK-293 cells. The viruses were purified, using the Adenovirus Mini Purification Virakit (Virapur), and titered, using the Adeno-X Rapid Titer Kit (Clontech).

Immunoprecipitation and Quantitative Immunoblotting.

Coimmunoprecipitation was performed using anti-HRC and Fam20C antibodies and cardiac homogenates from WT (Ser96) HRC hearts (1 mg of total protein). The precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HRC and anti-Fam20C antibodies. Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE (8–10%) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies. Primary antibodies were HRC (1:1,000) and Fam20C (1:1,000) obtained from Sigma–Aldrich. The horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:5,000) were from Amersham Biosciences. The membranes were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence Western blot analysis detection system (Amersham Biosciences).

Flag-HRC, Flag-HRC-Ser96Ala, Flag-HRC-Ser96Asp, HA Fam20C-D478A (WT and/or DA), and V5-SERCA2a/triadin were expressed in H9C2 cells or Fam20C WT or KO U20S cells (18) as indicated. Proteins were immunoprecipitated or coimmunoprecipitated by Flag (M2) antibody or V5 antibody, and were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag (1:1,000), anti-V5 (1:1,000), or anti-HA (1:1,000) antibodies (Sigma). Indicated samples were placed in phosphatase buffer and were incubated with 400 units of λ-phosphatase (New England Biolabs) for 1 h at 37 °C.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carolyn Worby and Jixin Cui for valuable input. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (Grant 3T32HL007444-34S1 to A.J.P., Grants DK018849-41 and DK018024-43 to J.E.D., and Grants HL26057 and HL64018 to E.G.K.), the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007-2013 under Grant Agreement HEALTH-F2-2009-241526 [EUTrigTreat (European Union Trigger Treatment)], and the Hellenic Cardiological Society.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. J.S. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1706441114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: The complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:531–547. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zipes DP, Wellens HJ. Sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 1998;98:2334–2351. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haghighi K, Bidwell P, Kranias EG. Phospholamban interactome in cardiac contractility and survival: A new vision of an old friend. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;77:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks AR. Calcium cycling proteins and heart failure: Mechanisms and therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:46–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI62834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arvanitis DA, Vafiadaki E, Sanoudou D, Kranias EG. Histidine-rich calcium binding protein: The new regulator of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium cycling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory KN, et al. Histidine-rich Ca binding protein: A regulator of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium sequestration and cardiac function. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:653–665. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park CS, et al. Targeted ablation of the histidine-rich Ca(2+)-binding protein (HRC) gene is associated with abnormal SR Ca(2+)-cycling and severe pathology under pressure-overload stress. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:344. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0344-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan GC, Gregory KN, Zhao W, Park WJ, Kranias EG. Regulation of myocardial function by histidine-rich, calcium-binding protein. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1705–H1711. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01211.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arvanitis DA, et al. The Ser96Ala variant in histidine-rich calcium-binding protein is associated with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2514–2525. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh VP, et al. Abnormal calcium cycling and cardiac arrhythmias associated with the human Ser96Ala genetic variant of histidine-rich calcium-binding protein. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000460. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tagliabracci VS, et al. Secreted kinase phosphorylates extracellular proteins that regulate biomineralization. Science. 2012;336:1150–1153. doi: 10.1126/science.1217817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tagliabracci VS, et al. A single kinase generates the majority of the secreted phosphoproteome. Cell. 2015;161:1619–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tagliabracci VS, Pinna LA, Dixon JE. Secreted protein kinases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundby A, et al. Quantitative maps of protein phosphorylation sites across 14 different rat organs and tissues. Nat Commun. 2012;3:876. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundby A, et al. In vivo phosphoproteomics analysis reveals the cardiac targets of β-adrenergic receptor signaling. Sci Signal. 2013;6:rs11. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tagliabracci VS, et al. Dynamic regulation of FGF23 by Fam20C phosphorylation, GalNAc-T3 glycosylation, and furin proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5520–5525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402218111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han P, et al. Catecholaminergic-induced arrhythmias in failing cardiomyocytes associated with human HRCS96A variant overexpression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1588–H1595. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01153.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoshan-Barmatz V, et al. The identification of the phosphorylated 150/160-kDa proteins of sarcoplasmic reticulum, their kinase and their association with the ryanodine receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1283:89–100. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(96)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tibaldi E, Arrigoni G, Cozza G, Cesaro L, Pinna LA. “Genuine” casein kinase: The false sister of CK2 that phosphorylates secreted proteins at S-x-E/pS motifs. In: Ahmed K, Issinger O-G, Szyszka R, editors. Protein Kinase CK2 Cellular Function in Normal and Disease States. Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: 2015. pp. 227–237. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasano T, Kikuchi K, McDonald AD, Lai S, Donahue JK. Targeted high-efficiency, homogeneous myocardial gene transfer. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:954–961. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson MA, et al. Mutations in FAM20C are associated with lethal osteosclerotic bone dysplasia (Raine syndrome), highlighting a crucial molecule in bone development. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:906–912. doi: 10.1086/522240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan HC, et al. Altered enamelin phosphorylation site causes amelogenesis imperfecta. J Dent Res. 2010;89:695–699. doi: 10.1177/0022034510365662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rafaelsen SH, et al. Exome sequencing reveals FAM20c mutations associated with fibroblast growth factor 23-related hypophosphatemia, dental anomalies, and ectopic calcification. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1378–1385. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui J, et al. A secretory kinase complex regulates extracellular protein phosphorylation. Elife. 2015;4:e06120. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber S, et al. SIX2 and BMP4 mutations associate with anomalous kidney development. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:891–903. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Research Council . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th Ed National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haas W, et al. Optimization and use of peptide mass measurement accuracy in shotgun proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1326–1337. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500339-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tolonen AC, Haas W. Quantitative proteomics using reductive dimethylation for stable isotope labeling. J Vis Exp. 2014;89:51416. doi: 10.3791/51416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao J, Tagliabracci VS, Wen J, Kim SA, Dixon JE. Crystal structure of the Golgi casein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:10574–10579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309211110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]