Abstract

In response to rising Medicare costs, Congress passed the Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act in 2015. The law fundamentally changes the way that health care providers are reimbursed by implementing a pay for performance system that rewards providers for high-value health care. As of the beginning of 2017, providers will be evaluated on quality and in later years, cost as well. High-quality, cost-efficient providers will receive bonuses in reimbursement, and low-quality, expensive providers will be penalized financially. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will evaluate provider costs through episodes of care, which are currently in development, and alternative payment models. Although dialysis-specific alternative payment models have already been implemented, current models do not address the transition of patients from CKD to ESRD, a particularly vulnerable time for patients. Nephrology providers have an opportunity to develop cost-efficient ways to care for patients during these transitions. Efforts like these, if successful, will help ensure that Medicare remains solvent in coming years.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, dialysis, Economic Impact, nephrology

Medicare makes up approximately 15% of the federal budget and costs the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) close to $700 billion in 2016.1 Although patients with kidney disease make up 11.7% of Medicare beneficiaries, they account for a disproportionate 28% of total Medicare costs.2,3 Furthermore, Medicare’s annual costs are projected to increase to $1.2 trillion in the next decade, most of it paid for by deficit spending.1 Although many factors contribute to the rise in Medicare spending, most health economists have argued that an underlying fee for service system has played a major role.4–8

To address Medicare’s rising costs, the government passed the Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (MACRA) in 2015.9 The law garnered bipartisan support (House: 392–37, Senate: 92–8), with policymakers eager to replace traditional fee for service, which rewards providers for volume of services, with value-based reimbursement.

Financial Risk and Fee for Service

Understanding the MACRA requires a brief digression. All patients face the unfortunate uncertainty of illness, which constitutes a major financial risk due to the high costs of health care. Insurance reduces this risk by paying for expensive care when it becomes necessary. These payouts are financed either by premiums (in the case of private insurance) or taxes and government borrowing (in the case of public insurance, like Medicare). Ultimately, patients and taxpayers end up shouldering the burden of increased health spending.

In the traditional fee for service model, the financial risk of high-cost care falls squarely on insurers and thus, patients and taxpayers. As a result, health care providers face little to no risk, because they are generally paid at or above marginal cost for each service. Because the system rewards quantity over quality, health care providers have a strong incentive to overtreat patients, sometimes providing services with little concrete benefit or even harm. A recent study of Medicare fee for service care in hospitalized patients found that physician spending was highly variable but that more expensive providers had no better 30-day mortality or readmissions than less expensive providers.10

Before the implementation of the ESRD prospective payment system, fee for service reimbursement for injectable medications likely led to the overuse of erythropoietin in dialysis. Despite a preponderance of randomized data showing that too much erythropoietin harms patients,11–15 dialysis providers continued to target inappropriately high hemoglobin levels in excess of contemporary guideline recommendations.16,17 Both the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission18 and the US Government Accountability Office19 argued that bundling payments would likely temper these rising costs and overuse. Because the prospective payment system bundled injectable medications into a single dialysis payment, there has been a dramatic decrease in erythropoietin use concurrent with a drop in death, strokes, and heart attacks.20

Enter the MACRA

Before the MACRA, the government attempted to address the rising cost of care by imposing a strict cap on Medicare’s payments to physicians, known as the Sustained Growth Rate (SGR). As a blunt instrument, the SGR did not eliminate the incentive to overtreat patients, and it did not improve the quality of health care. Accordingly, it became the perennial target of physician and patient groups.21–24 In the years leading up to the MACRA, Congressional leaders repeatedly voted to postpone the SGR’s cuts in response to this criticism.

Eventually, Congress passed the MACRA, which replaced the defunct SGR with a system that rewards providers for delivering high-value health care. It does this by requiring providers to take part in one of two tracks: the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) or the advanced Alternative Payment Models (advanced APMs).9 Both tracks use a two-pronged approach to assess value in health care delivery: quality and cost. Rather than pay providers for rendered services, regardless of outcome, the CMS will financially reward providers who deliver high-quality, low-cost health care. By holding providers accountable, the MACRA effectively transfers financial risk from taxpayers and patients to providers.

The MIPS

Initially, the majority of providers will participate in the MIPS, because they will not have the infrastructure necessary to form an advanced APM.25 Under the MIPS, the MACRA assesses provider value through quality reporting measures (formerly known as the Physician Quality Reporting System) and episodes of care, which measure costliness (previously the Value-Based Performance Metrics). The program also requires that providers participate in clinical practice improvement activities and have an electronic health record (previously the Meaningful Use program). Performance along these dimensions is scored, and providers will receive bonuses or deductions: up to 4% of total payments in 2019, ramping up to 9% of total payments by 2022.25

Quality Reporting under the MIPS

The quality performance category requires providers to report on six measures of their choice, including one outcome measure. The CMS will evaluate providers on their performance relative to their peers.26 Although >270 measures are available, only a few are specific to nephrology (Table 1). Because the CMS allows providers to report on any of the listed measures, nephrology providers have the option to report on non-nephrology conditions that are common to their practice, such as congestive heart failure, diabetes, and falls. However, doing so may not be advantageous, because they would be compared with providers who specialize in these other diseases.

Table 1.

Nephrology-specific quality measures under the MIPS

| Quality Measure |

|---|

| Adult kidney disease: BP managementa |

| Adult kidney disease: catheter at initiation of hemodialysisa |

| Adult kidney disease: catheter use for ≥90 da |

| Adult kidney disease: referral to hospice |

| Pediatric kidney disease: adequacy of volume management |

| Pediatric kidney disease: patients with ESRD receiving dialysis: hemoglobin level <10 g/dla |

Outcome measure.

Furthermore, providers have the option to report as a group through a medical group’s tax identification number.25 Providers of large medical groups may find it beneficial to consolidate their reporting, mitigating the effect of outliers. Multispecialty group practices will also have the option to select their six best-performing measures across all specialties. As a result, poorly performing nephrologists in group practices might avoid reporting any quality metrics and depend on better performing specialties.

Nephrology providers with small volume practices (especially single specialty practices in rural areas) may find it difficult to adapt, because they will be unable to shield risk. The paucity of nephrology-specific metrics could accentuate these difficulties by forcing nephrologists to compete with primary care doctors and other specialists on non-nephrology measures. To address this concern, the CMS will exempt most providers with low patient or low payment volume from the MIPS.25 Additionally, starting in 2018, small practices with fewer than ten providers can consolidate with others to report as virtual groups. Still, many stakeholders, including the American Society of Nephrology, contend that additional quality measures need to be developed, particularly outcome-oriented measures.25,27,28 To ensure that the MIPS meaningfully promotes the health of patients with kidney disease, the nephrology community will need to work closely with the CMS to develop additional nephrology-specific metrics.

Episodes of Care under the MIPS

To assess provider cost, the MACRA mandates the use of episodes of care. An episode encompasses the treatment, aftercare (including postacute care), and complications associated with a specific clinical condition or procedure (Figure 1).29 For instance, an episode for AKI might include the initial hospitalization, outpatient follow-up and laboratories, and complications, such as a readmission for poor volume management. The episode would exclude clinically unrelated services, such as an elective hernia repair. By incorporating complications into the episode, the CMS will penalize providers who try to lower their costs by skimping on necessary care. Likewise, overly cautious providers with unnecessarily expensive treatment costs will also see decreases in reimbursement.

Figure 1.

An example of an AKI episode. Here, we show medical services rendered to a patient over time. Although the majority of care is related to AKI and grouped into the episode, the elective hernia repair is not related and thus, is excluded.

Although it represents a large change from the status quo, the MIPS maintains the fee for service system. Providers will still receive payments for each service within an episode. Instead, episode costs will be used to adjust payments. That is, the CMS will use risk-adjusted episode costs to evaluate providers, with cheaper providers receiving higher payments and expensive providers facing reimbursement cuts. Episodes upend traditional fee for service incentives by encouraging providers to focus on longitudinal disease management rather than discretized point of care. Although episodes will not be used to bundle payments, they are similar in that they make providers accountable for expensive behavior. Should episodes prove successful in controlling costs, they could potentially be used to bundle future payments.

Nephrology providers will not be subject to episode-based cost measures until payment year 2020 (performance year 2018) at the earliest.25 This is due to the CMS’s decision to exclude cost metrics from the MIPS for the current year. Additionally, nephrology-centric episodes are still under development. The CMS has announced plans to develop nephrology-specific episodes, including CKD.29 Although AKI has not been announced as an episode group, given the high frequency of complications associated with AKI, the CMS may decide to develop AKI episodes in the future. Although the details of these nephrology-specific episode groups are not yet developed, they will likely reward providers who reduce complications, such as admissions for volume overload or cardiovascular events.

The success of these episode groups depends, in part, on the creation of homogeneous conditions that can be readily compared using standard risk adjustment. Otherwise, providers may be unfairly penalized for taking care of sicker populations. Care for AKI and CKD is highly dependent on disease severity, and the corresponding episode groups should take this into account. For instance, patients with AKI requiring dialysis will cost more than those with mild AKI. Similarly, patients with CKD stage 4 or 5 often require expensive adjuncts, including erythropoietin-stimulating agents and medications to manage bone-mineral metabolism.

Episodes for advanced CKD, in particular, must be developed carefully. A poorly constructed episode for CKD stage 5 could inadvertently reward providers for not planning for dialysis or transplant. If these episodes do not include dialysis-related complications, they will disincentivize preemptive preparation for dialysis. Determining the appropriate timeframe for accountability will require input from the nephrology community in conjunction with empirical analysis. To ensure that episodes do not harm patients, nephrology providers will need to engage the CMS and provide detailed guidance on the definition of these episode groups.

The Advanced APM

Instead of the MIPS, providers may opt for the advanced APM track. APMs are provider models that emphasize coordination of care, tying reimbursement to value.25 They can focus on specific diseases or populations and span a variety of specialties, including primary care, cardiology, cardiothoracic surgery, orthopedic surgery, oncology, and nephrology.30 Although every APM is structured differently, the CMS requires that all APMs must take on more than a nominal amount of financial risk.25

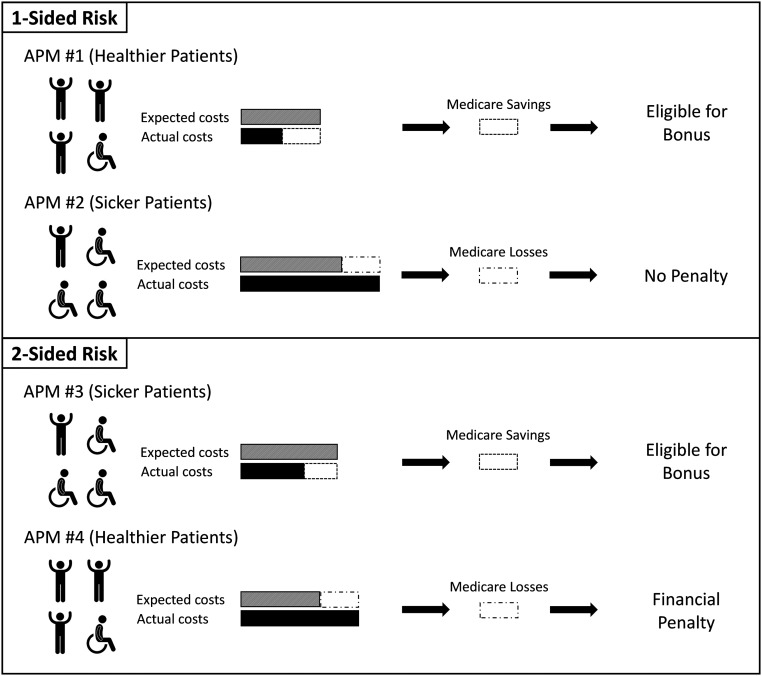

Here, the CMS explicitly defines financial risk as Medicare-shared savings or losses. That is, the CMS will compute the expected annual cost for an APM on the basis of their pool of patients and compare it with the provider’s actual cost (Figure 2).31 Expected costs take into account patient factors through risk adjustment: sicker patients will have higher expected costs. Although episodes focus on the costs of a specific condition, APMs expose providers to total expected costs. The difference in expected and actual costs translates into savings or losses, which the CMS shares with the provider through one- or two-sided risk. With one-sided risk, the APM receives a proportion of shared savings but is shielded from shared losses. In two-sided risk, providers share both savings and losses. The share of savings or losses is calculated using determinants that include type of APM, number of beneficiaries, and quality score.

Figure 2.

Calculating shared savings and losses for the APMs. The CMS takes the population of patients within an APM and computes the risk-adjusted expected cost for the year. The APMs (2 and 3) that have sicker populations of patients will have higher expected costs. The APMs’ actual costs are then compared with expected costs. For providers taking on one-sided risk (1 and 2), if actual costs are less than expected costs, the APMs receive a portion of the shared savings as a bonus. However, if actual costs exceed expected costs, one-sided risk APMs are shielded from the loss and do not pay a penalty. In this case, APM 2 was more expensive than expected but does not owe the CMS any penalty. The APMs with two-sided risk (3 and 4) are susceptible to both shared savings and losses, which lead to bonuses or penalties, respectively. Bonuses and penalties are calculated as a portion of shared savings and losses and determined using factors that include type of APM, number of beneficiaries, and quality score.

Importantly, the CMS distinguishes between nonadvanced APMs and advanced APMs on the basis of the amount of risk taken by the provider. To qualify as an advanced APM, the provider is usually required to take on two-sided risk. Advanced APMs also must progressively increase this risk over time, with at least 75% of payments exposed to shared savings and losses by 2021 (Table 2).32 In return, they will receive a 5% lump sum bonus from the previous year’s Part B payments. Advanced APMs have the added benefit of exemption from the MIPS. Conversely, nonadvanced APMs do not receive the lump sum bonus and are still subject to the MIPS quality- and episode-based cost measures, although they are still eligible for shared savings.

Table 2.

Required share of Medicare payments or patients to qualify as an advanced APM

| Year | Either | |

|---|---|---|

| Medicare Payments, % | Medicare Patients, % | |

| 2017 | 25 | 20 |

| 2018 | 25 | 20 |

| 2019 | 50 | 35 |

| 2020 | 50 | 35 |

| 2021 | 75 | 50 |

| 2022 and after | 75 | 50 |

Alongside cost assessment, the CMS also holds APMs accountable for their quality.30 The quality metrics for APMs are specifically tailored for each provider model and are generally more stringent than in the MIPS. They also form an important counterbalance to the providers’ incentive to maximize shared savings. The APMs that do not meet minimum quality thresholds are not eligible to receive shared savings for the year. By tying quality to cost, the CMS enhances value by reducing the incentive to undertreat patients.

One criticism of the more inclusive cost measures used to calculate shared savings and losses is that they count costs from clinically unrelated services. Episodes reduce this noise by limiting costs to relevant clinical services. Proponents for APMs suggest a theoretical benefit of increased care coordination, to the extent that treatments across different diseases overlap (e.g., laboratory or radiology studies that are shared across multiple illnesses).33–35 Because episodes potentially include related costs from different providers, they also may encourage care coordination. It remains to be seen which risk-sharing measure more effectively curbs Medicare costs.

The Comprehensive ESRD Care Model is a dialysis-specific APM.36–38 Dialysis providers that make up these APMs are known as ESRD Seamless Care Organizations (ESCOs). Large dialysis organizations (LDOs) that participate in an ESCO are required to take on two-sided risk, whereas non-LDOs may opt for one-sided risk. However, to qualify as an advanced APM, an ESCO (LDO and non-LDO) must take on two-sided risk.

ESCOs are evaluated on strict quality measures to ensure they are not withholding medical care at the expense of patient health (Table 3).39,40 They span a variety of process and outcome metrics across multiple disciplines and include Quality Incentive Program measures, such as vascular access and dialysis adequacy; patient-centered outcomes, like the Kidney Disease Quality of Life Survey; standardized ratios for admissions, mortality, and readmission; and process measures for diabetes care and vaccination. The CMS also evaluates care coordination measures, such as medication reconciliation and advanced care planning, which may reduce complications and overall health care spending.41 If the ESCO does not meet the minimum required quality score, it is ineligible for shared savings. By responding to incentives that reward value, dialysis providers and nephrologists have a unique opportunity to show that they can improve health care delivery in a cost-conscious manner.

Table 3.

Quality measures for ESCOs

| Quality Measure | Measure Type |

|---|---|

| Hemodialysis vascular access | QIP Process |

| Maximizing placement of arterial venous fistulas | |

| Minimizing use of catheters | |

| Bloodstream infections in hemodialysis outpatients | QIP Outcome |

| Hemodialysis/peritoneal dialysis adequacy | QIP Outcome |

| Proportion of patients with hypercalcemia | QIP Outcome |

| In-Center Hemodialysis Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers and Systems survey | QIP Outcome |

| Kidney disease quality of life survey | Outcome |

| Standardized hospitalization ratio for admissions | Outcome |

| Standardized mortality ratio | Outcome |

| Standardized readmission ratio | QIP Outcome |

| Documentation of current medications | Process |

| Falls: screening, risk assessment, plan of care | Process |

| Advance care plan | Process |

| Diabetes care | Process |

| Eye examination | |

| Foot examination | |

| Immunizations for the ESRD population | Process |

| Influenza | |

| Pneumonia | |

| Screening for clinical depression and follow-up plan | QIP Process |

| Tobacco use: screening and cessation intervention | Process |

QIP, Quality Incentive Program.

In addition to ESCOs, there may be future opportunities for improving the transition from CKD to ESRD. The years before and after the initiation of dialysis are the most expensive and vulnerable period of time for a patient with kidney disease.42 Despite over 10 years of efforts to promote fistula use in hemodialysis, the proportion of patients starting with a catheter has remained at 80.3%.2 Dialysis providers, in part due to the Fistula First campaign and the ESRD Quality Incentive Program, eventually do transition these patients off catheters.43–45 By the end of the first year of dialysis, the proportion of patients dialyzing through a catheter drops to 20%.2 These findings suggest that fistulas and grafts could be placed earlier in many of these patients, before dialysis initiation.

One downside to earlier access placement is the potential increase in unnecessary fistulas and grafts in patients who never progress to ESRD.27,46 Further complicating this issue is that many patients may opt for peritoneal dialysis, preemptive transplant, or conservative care. APMs that bridge the transition from late-stage CKD to ESRD could solve this dilemma by focusing on value in a patient-centered way. Such an APM could include outcome metrics, like catheter-related infections in the first 90 days of dialysis, and process measures incentivizing patient-centered decision making. The CMS could also hold providers accountable for the number of patients with unnecessary fistulas and grafts as well as the expenses from unnecessary access maintenance. By emphasizing value, these APMs could revolutionize the way that we currently think about the transition to ESRD. The National Kidney Foundation and Renal Physicians Association have already set out to develop a late-stage CKD model to improve the health of this vulnerable population.28

Future Challenges

Although episode- and APM-based cost measures will undergo standard risk adjustment, statistical models cannot completely eliminate normal fluctuations in cost and quality. For providers with small populations of patients, outliers have a strong influence on any metric, and even high-performing providers might be subjected to financial penalties from poor outcomes in a few patients. Although the CMS will exempt providers with low patient or payment volume, medium-sized practices may find this financial risk unpalatable. Many providers may consolidate to mitigate risk exposure, and in large and medium population areas, small private practice nephrology might become financially untenable. Similarly, small- and medium-sized dialysis APMs (non-LDO ESCOs) may find it difficult to take on two-sided risk to become an advanced APM without consolidating further. Being unable to qualify as an advanced APM has important financial repercussions, because nonadvanced APMs do not receive a lump sum bonus and must remain in the MIPS. If consolidation does occur, nephrologists will need to adapt to stay financially competitive.

For the MACRA to succeed, the CMS will need to find the right balance between quality and cost. Overemphasizing cost-conscious care may incentivize undertreating patients. However, quality metrics in a vacuum may lead to exorbitant bills. In many cases, cost measures have a built-in disincentive for inappropriately skimping on care, because medical complications are usually expensive. However, some complications, such as mortality, do not result in additional spending. To ensure that patients with kidney disease are receiving high-value care, the nephrology community will need to work closely with the CMS to develop effective quality and cost metrics.

Looking Forward

Because patients with kidney disease are some of the most expensive and complicated to care for, nephrology providers have a unique opportunity to respond to the MACRA with innovation by developing ways to realign care cost efficiently while preserving quality. Some nephrology providers will act on the temptation to resist these changes and push back against Medicare payment reform. In doing so, they will forfeit the chance to shape a system that delivers high-value health care. It is possible that, in response to criticism, the CMS inches back toward a fee for service system and one that rewards overtreatment. Doing so would likely accelerate Medicare spending growth and hasten its financial collapse. By embracing the MACRA’s changes, not only would nephrology providers have the opportunity to receive monetary rewards, but also, they would help Medicare stay solvent in the future. As a result, patients will benefit from having a better health care system.

Disclosures

Although the authors are affiliated with Acumen, LLC, our manuscript was not funded or supported by Acumen, LLC and is solely the work of the authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) of the National Institutes of Health. E.L. is supported by NIDDK grant F32DK107123. The work of J.B. on this paper is partially supported by National Institute on Aging grants P30AG017253 and R37AG036791.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Congressional Budget Office. The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, 2017. Available at: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/52370-outlookonecolumn.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2017

- 2.United States Renal Data System : 2016 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States 2, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Renal Data System : 2016 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States 1, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenheimer T: High and rising health care costs. Part 3: The role of health care providers. Ann Intern Med 142: 996–1002, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glied S: Health care costs: On the rise again. J Econ Perspect 17: 125–148, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mongan JJ, Ferris TG, Lee TH: Options for slowing the growth of health care costs. N Engl J Med 358: 1509–1514, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orszag PR, Ellis P: The challenge of rising health care costs--a view from the Congressional Budget Office. N Engl J Med 357: 1793–1795, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health Affairs: Breaking the Fee-for-Service Addiction: Let’s Move to a Comprehensive Primary Care Payment Model. Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/08/17/breaking-the-fee-for-service-addiction-lets-move-to-a-comprehensive-primary-care-payment-model/. Accessed March 30, 2017

- 9.Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, Pub. L. 114-10, 129 Stat. 87, 2015. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ10/PLAW-114publ10.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2017

- 10.Tsugawa Y, Jha AK, Newhouse JP, Zaslavsky AM, Jena AB: Variation in physician spending and association with patient outcomes. JAMA Intern Med 177: 675–682, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phrommintikul A, Haas SJ, Elsik M, Krum H: Mortality and target haemoglobin concentrations in anaemic patients with chronic kidney disease treated with erythropoietin: A meta-analysis. Lancet 369: 381–388, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, Barnhart H, Sapp S, Wolfson M, Reddan D; CHOIR Investigators : Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 355: 2085–2098, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Besarab A, Bolton WK, Browne JK, Egrie JC, Nissenson AR, Okamoto DM, Schwab SJ, Goodkin DA: The effects of normal as compared with low hematocrit values in patients with cardiac disease who are receiving hemodialysis and epoetin. N Engl J Med 339: 584–590, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drüeke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, Eckardt KU, Macdougall IC, Tsakiris D, Burger HU, Scherhag A; CREATE Investigators : Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med 355: 2071–2084, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Eckardt KU, Feyzi JM, Ivanovich P, Kewalramani R, Levey AS, Lewis EF, McGill JB, McMurray JJ, Parfrey P, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Singh AK, Solomon SD, Toto R; TREAT Investigators : A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 361: 2019–2032, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pizzi LT, Patel NM, Maio VM, Goldfarb DS, Michael B, Fuhr JP, Goldfarb NI: Economic implications of non-adherence to treatment recommendations for hemodialysis patients with anemia. Dial Transplant 35: 660–671, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins AJ, Ebben JP, Gilbertson DT: EPO adjustments in patients with elevated hemoglobin levels: Provider practice patterns compared with recommended practice guidelines. Am J Kidney Dis 49: 135–142, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission: Report to the Congress: Modernizing the Outpatient Dialysis Payment System, 2003. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/oct2003_Dialysis.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed May 3, 2017

- 19.United States Government Accountability Office. End-Stage Renal Disease: Bundling Medicare's Payment for Drugs with Payment for All ESRD Services Would Promote Efficiency and Clinical Flexibility. GAO-07-77, 2006. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/assets/260/253347.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2017

- 20.Chertow GM, Liu J, Monda KL, Gilbertson DT, Brookhart MA, Beaubrun AC, Winkelmayer WC, Pollock A, Herzog CA, Ashfaq A, Sturmer T, Rothman KJ, Bradbury BD, Collins AJ: Epoetin alfa and outcomes in dialysis amid regulatory and payment reform. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 3129–3138, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClellan M, Patel K, Sanghavi D: Medicare physician payment reform: Will 2014 be the fix for SGR? JAMA 311: 669–670, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilensky GR: Improving value in Medicare with an SGR fix. N Engl J Med 370: 1–3, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilensky GR: Developing a viable alternative to Medicare’s physician payment strategy. Health Aff (Millwood) 33: 153–160, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wynne B: For Medicare’s new approach to physician payment, big questions remain. Health Aff (Millwood) 35: 1643–1646, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Program; Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and Alternative Payment Model (APM) Incentive under the Physician Fee Schedule, and Criteria for Physician-Focused Payment Models CMS-5517-FC. Federal Register: 81 FR 77008, 77008-77831, 2016. Available at: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-11-04/pdf/2016-25240.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2017 [PubMed]

- 26.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), 2016. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/Merit-based-Incentive-Payment-System-MIPS-Overview-slides.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2017

- 27.Shechter SM, Skandari MR, Zalunardo N: Timing of arteriovenous fistula creation in patients with CKD: A decision analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 95–103, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Kidney Foundation: Re: CMS-1651-P: Medicare Program; End-Stage Renal Disease Prospective Payment System, Coverage and Payment for Renal Dialysis Services Furnished to Individuals with Acute Kidney Injury, End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program, Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics, Orthotics and Supplies Competitive Bidding Program Bid Surety Bonds, State Licensure and Appeals Process for Breach of Contract Actions, Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics, Orthotics and Supplies Competitive Bidding Program and Fee Schedule Adjustments, Access to Care Issues for Durable Medical Equipment; and the Comprehensive End-Stage Renal Disease Care Model, 2016. Available at: https://www.kidney.org/sites/default/files/20160818%20NKF%20response%20to%20questions%20on%20APMS%20in%202017%20ESRD%20PPS%20QIP.PDF. Accessed March 30, 2017 [PubMed]

- 29.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Episode-Based Cost Measure Development for the Quality Payment Program, 2016. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/Episode-Based-Cost-Measure-Development-for-the-Quality-Payment-Program.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2017

- 30.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Alternative Payment Models in the Quality Payment Program, 2017. Available at: https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_Advanced_APMs_in_2017.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2017

- 31.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accountable Care Organizations: What Providers Need to Know. ICN 907406, 2016. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/ACO_Providers_Factsheet_ICN907406.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2017

- 32.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: The Quality Payment Program Overview Fact Sheet, 2016. Available at: https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/Quality_Payment_Program_Overview_Fact_Sheet.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2017

- 33.Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Bertko J, Lieberman SM, Lee JJ, Lewis JL, Skinner JS: Fostering accountable health care: Moving forward in medicare. Health Aff (Millwood) 28: w219–w231, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClellan M, McKethan AN, Lewis JL, Roski J, Fisher ES: A national strategy to put accountable care into practice. Health Aff (Millwood) 29: 982–990, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES: Primary care and accountable care--Two essential elements of delivery-system reform. N Engl J Med 361: 2301–2303, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.CEC Initiative: Appendix B: LDO Financial Methodology, 2015. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/cec-financial-ldo.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2017

- 37.CEC Initiative: Appendix B: Financial Methodology (Non-LDO CEC Model), 2015. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/cec-financial-nonldo.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2017

- 38.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Comprehensive ESRD Care Model Fact Sheet, 2014. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2014-Fact-sheets-items/2014-04-15.html. Accessed March 30, 2017

- 39.CEC Initiative: Appendix D. Quality Performance (LDO), 2017. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/cec-qualityperformance-ldo.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2017

- 40.CEC Initiative: Appendix D. Quality Performance (non-LDO), 2017. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/cec-qualityperformance-nonldo.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2017

- 41.Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J: Physician visits and 30-day hospital readmissions in patients receiving hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2079–2087, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.United States Renal Data System : USRDS 2010 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States 1, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vassalotti JA, Jennings WC, Beathard GA, Neumann M, Caponi S, Fox CH, Spergel LM; Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative Community Education Committee : Fistula first breakthrough initiative: Targeting catheter last in fistula first. Semin Dial 25: 303–310, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.LWW: Achieving the Goal: Results from the Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. Available at: http://journals.lww.com/co-nephrolhypertens/Fulltext/2011/11000/Achieving_the_goal___results_from_the_Fistula.4.aspx. Accessed March 30, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ESRD QIP Summary: Payment Years 2014–2018, 2016. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/ESRDQIPSummaryPaymentYears2014-2018.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2017

- 46.Oliver MJ, Quinn RR, Garg AX, Kim SJ, Wald R, Paterson JM: Likelihood of starting dialysis after incident fistula creation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 466–471, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]