Abstract

Paper-based microfluidics has attracted attention for the last ten years due to its advantages such as low sample volume requirement, ease of use, portability, high sensitivity, and no necessity to well-equipped laboratory equipment and well-trained manpower. These characteristics have made paper platforms a promising alternative for a variety of applications such as clinical diagnosis and quantitative analysis of chemical and biological substances. Among the wide range of fabrication methods for microfluidic paper-based analytical devices (μPADs), the wax printing method is suitable for high throughput production and requires only a commercial printer and a heating source to fabricate complex two or three-dimensional structures for multipurpose systems. μPADs can be used by anyone for in situ diagnosis and analysis; therefore, wax printed μPADs are promising especially in resource limited environments where people cannot get sensitive and fast diagnosis of their serious health problems and where food, water, and related products are not able to be screened for toxic elements. This review paper is focused on the applications of paper-based microfluidic devices fabricated by the wax printing technique and used for international health. Besides presenting the current limitations and advantages, the future directions of this technology including the commercial aspects are discussed. As a conclusion, the wax printing technology continues to overcome the current limitations and to be one of the promising fabrication techniques. In the near future, with the increase of the current interest of the industrial companies on the paper-based technology, the wax-printed paper-based platforms are expected to take place especially in the healthcare industry.

I. INTRODUCTION

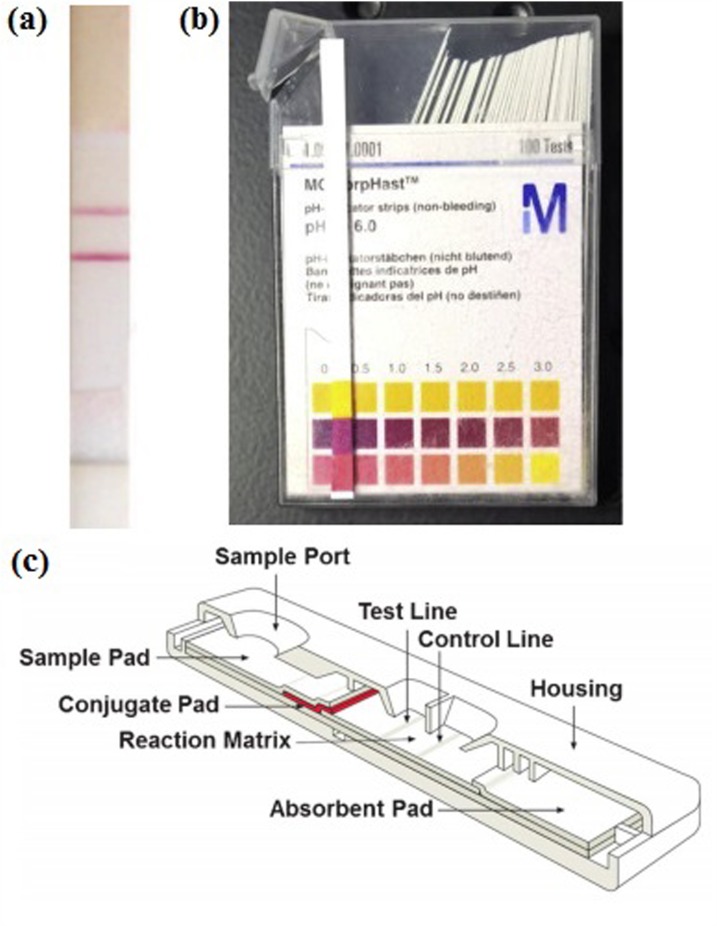

The preliminary steps towards paper-based microfluidic devices, which have become highly popular since 2009, were taken more than a century ago. In 1883, the first popular paper strips for sugar and albumin test were proposed1 and 40 years after, Feigl and Matthews employed filter paper for the first time to carry out colorimetric assays using the principles of the capillary action.2 Parallel to these improvements, urinary diagnostic tests on paper strips have been performed starting from 1930s1 and have become commercially available since 1960s.3 Those commercial devices which are called dipstick devices due to the basis of dipping them into the urine specimen have become widely popular and been adapted to various chemical analytes; e.g., proteins, ketones, and hemoglobin. The results are either qualitative or semi-quantitative. While the qualitative test result is screened as yes or no on the strip, [Fig. 1(a) (Ref. 4)] semi-quantitative dipstick tests are mostly based on a color change in the presence of an analyte in the sample [Fig. 1(b) (Ref. 5)]; hence, these dipstick devices require a colorimetric chart or additional equipment for readout [Fig. 1(c)].

FIG. 1.

(a) Common qualitative test strip for immunoassay. Reprinted with permission from Liu et al., Electroanalysis 26, 1214 (2014). Copyright 2014 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. (b) Common semi quantitative dipstick test for pH determination and colorimetric readout. Reprinted with permission from Morbioli et al., Anal. Chim. Acta 970, 1 (2017). Copyright 2017 Elsevier B.V. (c) Representation of LFA device. Reprinted with permission from Yetisen et al., Lab Chip 13, 2210 (2013). Copyright 2013 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

In the 80s, the first commercial lateral flow assay (LFA) strips were developed for home pregnancy tests.6 After their popularity, this technology started to be widely used in the clinical, veterinary, agricultural, and food industries, bio- defense, and environmental applications.7 The principle of the LFA is based on the lateral travelling of the sample such as urine, saliva, sweat, serum, plasma, or whole blood8 by the help of a capillary action and can basically be accomplished by the following steps: (1) addition of the sample (e.g., urine), (2) binding of the target analyte (if exists) to the antibodies conjugated to the color giving particles in the reaction zone, and (3) washing of the excess reagents. The test strips consist of four zones: Sample Pad, conjugate pad, reaction zone, and absorbent zone as shown in Fig. 1(d).9

The reasons behind the wide acceptance and usage of these LFA strips are the simplicity of the device preparation, inexpensiveness, and preservability for very long times and under variable environmental conditions. Additionally, LFA requires small sample sizes and very simple operational steps to carry out the test. Despite these advantages, LFA does not provide quantitative results and multiplex detection, and mostly results in cross-reactivity. Even though there are many research activities10–13 to improve the qualifications of LFA, low sensitivity (mostly based on “yes or no” result) and low reproducibility are the major drawbacks for early and highly sensitive detection of many diseases.14 In order to struggle with these issues, the researchers started to give some thought on developing novel diagnostic devices.9 As one of these technologies, the integrated microfluidic devices which have been employed for over twenty years15 have become more popular due to the discovery of novel fabrication techniques such as soft lithography16 and hot embossing,17 which allow the use of polymers instead of brittle glass or expensive silicon wafer.18 The microfluidic devices, composed of microfluidic channels and chambers, are suitable for rapid-prototyping and point-of-care (POC) diagnosis, and also allow complexity and require a small sample volume.19 However, the polymers are not compatible with organic solvents and an external power source is required for the flow in polymer based channels.20

In recent years, multiple reviews focused on paper-based microfluidic POC diagnostic devices. Many of these reviews described the developments in paper-based microfluidic technologies,21–25 a detection method on microfluidic paper-based analytical devices (μPADs),4,5 the multistep processes in these paper-based devices,26 or reviewed separately the fabrication methods of the paper-based microfluidic devices.27 These reviews22,23 described the wax printing as one of the physical fabrication methods for μPADs. Li et al.23 limited the wax printing section by presenting its advantages but focusing mostly on its partial comparison with other fabrication methods.

More specifically, Rozand28 reviewed the paper-based analytical devices for POC diagnosis of infectious diseases. Ballerini et al.29 investigated a variety of paper-based materials and explained their functionality in POC diagnostic applications. Yetisen et al.9 published an extensive review on paper microfluidic technologies including fabrication methods, application areas, and a variety of sensing mechanisms. However, the wax printing part was limited, although mentioned as being one of the recent fabrication methods. Introducing a few studies only, they focused on the leading publications30,31 in the wax printing field.

The novel paper-based analytical devices, which are fabricated by wax-printing, are promising to meet the Affordable, Specific, Sensitive, User-friendly, Rapid, Equipment-free, and Deliverable (ASSURED) criteria. The wax printing method does not require any organic solvent or complex equipment. It can be controlled easily; it is cheap, robust, and fast. It allows very small designs and requires small sample sizes. Moreover, wax printing is suitable for mass production.9

The present review starts with the design and manufacturing of wax-printed μPADs for various applications including the biological ones, i.e., those that are used for international health (public health focusing on developing nations' diagnosis and therapy needs). Then, a short review is given about the Washburn equation and its uses for either in sample flow or wax spreading. Next, theoretical and computational approaches on capillary flow are presented. The rest of the paper is attributed to the biological applications of μPADs including cell cultivation, [electrochemiluminescence (ECL)] detection and analysis, colorimetric devices, and electrochemical (EC) immunoasssays, along with a comparison to conventional methods when possible. The comparison reveals the advantages and the limitations of the μPADs. We finally present the recent advances and the future directions of the μPADs.

II. DESIGN AND MANUFACTURING OF μPADs

A. Why to use μPAD?

Paper, which usually has a thickness of between 80 and 450 μm and a wide range of weight from 12 to 300 g m−2,32 is a multi-purpose material consisting of a cellulose fiber network with a porous structure. The hydrophilic nature of paper also allows capillary action to transport liquid without any external source of force.29 Apart from its physical properties, it is an inexpensive material. Having a cost of around 0.1 US cent dm−2, it is cheaper than most plastic substrates.

The process of making paper consists of several chemical and mechanical steps such as bleaching, pressing, and heating. There are also many steps in paper manufacturing according to its ultimate usage. For example, the pores between fibers may be filled with calcium carbonate, chalk, and clay in order to give the light scattering, ink absorbency, and smoothness or fluorescent agents for whitening. These characteristics of the paper change its physical properties such as flexibility, surface roughness, thermal stability, mechanical strength, and opacity.32 The production and modification processes of paper are sustainable and inexpensive. Another significant characteristic of paper is its biodegradability, which makes paper one of the most appropriate platforms for POC diagnostic devices. For example, Derda et al.,33 used chromatography paper for MDA-MB-231 cell line proliferation, since paper allows mechanical support for cell growth and the thickness of the paper is small enough such that oxygen can penetrate through it. In addition, a very small amount of wax is used in μPAD fabrication, and the paper can be destroyed easily by burning it with the wax on it on the contrary to chips made of thermoplastics.34 While paper has already been used since the 1800s for applications such as determining the acidity of solutions,29 paper chromatography,35 and urine analysis,36 only in recent years it has been used in the fabrication of lab-on-a-chips (LOC)s, which are the miniaturized forms of the conventional large scale analytical devices.29 LOCs provided a decrease in both the design and the assay cost compared to the large-scale laboratory setups.37 Paper has been considered as the platform for novel μPADs and reported for the first time by the Whitesides research group.38,39 These lab-on-paper devices allow immobilization of antibodies and enzymes since the carboxyl group on antibodies and the amino groups on cellulose are able to bond with each other.40 For this specific example, no complex instrument is needed and the test can be performed easily making μPADs good candidates to satisfy the ASSURED criteria.9

The fabrication of a wax printed μPAD is inexpensive and rapid. The time needed for the wicking and complete fluid distribution is around seconds and it increases with the number of paper layers used in the fabrication. For example, the whole fabrication process of the device presented in Fig. 2(a) takes less than 5 min and the total cost except the printer and the energy cost is $0.001 per device.30

FIG. 2.

(a) A μPAD prepared for the detection of glucose, protein, and cholesterol. Reprinted with permission from Carrilho et al., Anal. Chem. 81, 7091 (2009). Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society. (b) Wax patterned μPAD after heating. Reprinted with permission from Lu et al., Electrophoresis 30, 1497–1500 (2009). Copyright 2009 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim (c) Chambers at different width of wax printed barriers. Reprinted with permission from Carrilho et al., Anal. Chem. 81, 7091 (2009). Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

The wax printed channels are mostly compatible with aqueous solvents, but not with organic solvents. The wax does not behave as a barrier to certain organic solvents such as acetone; however in some cases, this may bring an advantage of easy cleaning of devices from the reagents and the samples.

B. Fabrication by wax printing

μPADs can be fabricated by several methods that can be classified mainly into two groups: forming the hydrophobic barriers as the walls of the microchannels or chambers and cutting the paper without forming a barrier. While the first group can be accomplished by many different techniques such as photolithography,41 inkjet etching,42,43 inkjet printing,44 ink stamping,45 plasma treatment,46 laser treatment,47,48 screen printing,49 and lacquer spraying50 which are mostly based on reagent deposition on the fiber surface and blocking of pores with reagents,23 the second group of devices is fabricated by mostly knife plotting51 or alternatively home cutting.52 These methods have both some advantages such as easy and rapid fabrication, high resolution, inexpensive reagent, and suitability to mass production as well as some disadvantages such as requirement of special equipment and low resistance to heat and poisonous reagents. For example, photolithography as a chemical process enables low-cost mass production; however, it needs expensive equipment and complex steps for fabrication.26 In the second group, knife plotting, which is a two dimensional shaping method, may require additional cutting steps to avoid the paper tearing.9

In order to overcome the disadvantages, various materials to form hydrophobic barriers were studied;22 consequently, paraffin and regular wax have been selected as the most promising ones. Wax patterning techniques have been studied since 1902 when Dieterich succeeded in creating an insulating barrier between two testing zones with the ultimate aim of preventing the cross-reactivity.53 Following that work, in 1937 Yagoda proposed a fabrication technique for chambers separated from each other by hydrophobic wax paraffin barriers54 and in 1949, Müller et al.55 used a paraffin paper along with a filter paper to form hydrophobic barriers in a similar way to wax-printing. They developed a paraffin impregnation method by using embossing and heating tools for the spreading process. The fabrication method was not easy to handle due to multi-step production.9 Parallel to these wax patterning techniques, μPADs patterned with hydrophobic materials other than wax have been studied.56 However, these methods still require external devices and extra controlling steps for fabrication. Lu et al.31 presented several advancements on fast fabrication of μPADs and the first proposed technique was based on patterning both sides of a filter paper with a wax crayon and heating the wax patterned paper in an oven for hydrophobic barrier formation. Even though this method was very simple and easy, the resolution of the patterning process was very low, which may pose a problem for devices with complex geometries.31 It was concluded that wax was a suitable and inexpensive material for creating the hydrophobic barriers, but the method was not applicable to mass production, based on labor cost and low resolution. Lu et al.31 and Carrilho et al.30 independently developed another technique, which was based on printing wax with a commercial wax printer. In this technique, the wax pen was replaced by a wax printer, which allows printing patterns in a resolution of up to 2400 × 2400 dpi. The designs could be drawn by various commercial software in digital media. That method could be used for mass production of devices, and suitable even with more complex geometries. It is thus shown that the whole fabrication process of the wax-printed μPADs, and the testing, the detection, and the analysis processes of the assays are easy, fast, and can be achieved with few equipment like a printer and a heater (Table I).57 A wax printed μPAD costs $0.001 per device of 1 cm2 since the cost of solid ink is around $0.0001/cm2 and the cost of a standard filter paper is around $7/m2.30 Moreover, it is not expensive to set up a laboratory for wax-printing since around $100058 is required for the two pieces of equipment that are needed, i.e., a wax printer (e.g., FUJIXEROX Phaser 8560, Japan is around $800) and a heater (around $200).58 A desktop scanner of around $100 might be used for the readout instead of an expensive monitoring equipment.59

TABLE I.

Parameters for wax printing.

| Printer | Paper | Temperature (°C) | Time | Design Software | Heating Equipment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xerox Phaser 8560DN | Filter paper 102 or 202 (Hangzhou Xinhua Paper Limited) | 150 | 2 min | … | Oven | 31 |

| Xerox Phaser 8560N | Whatman no.1 chromatography paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 150 | 2 min | CleWin (PhoeniX B.V.) | Hot plate | 30 |

| Xerox ColorQube 8570DN | Whatman no.1 chromatography paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 125 | 1 min | CorelDRAW (Corel Corp.) | Oven | 60 |

| Xerox Phaser 8560 | Whatman no.114 filter paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 150 | 2 min | Illustrator (Adobe Systems Inc.) | Oven | 33 |

| Xerox ColorQube 8750 | Whatman grade 4 filter paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 150 | 30 s | Illustrator (Adobe Systems Inc.) | Oven | 61 |

| Xerox ColorQube 8750N | Whatman grade 4 filter paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 120 | 5 min | … | Hot plate | 62 |

| Xerox ColorQube 8570 | Whatman no.1 chromatography paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 120 | 45 s | … | Oven | 63 |

| Xerox ColorQube 8570 | Whatman 3 MM chromatography paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 120 | 1 min | … | Oven | 63 |

| Xerox ColorQube 8750 | Whatman no.1 chromatography paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 160 | … | Microsoft Paint (Microsoft Corp.) | Laminator | 64 |

| Xerox Phaser 8560DN | Whatman no.1 chromatography paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 150 | 30 s | Illustrator (Adobe Systems Inc.) | Oven | 65 |

| Xerox ColorQube 8750 | Whatman no. 1 chromatography paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 150 | 2 min | Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc.) | Hot plate | 66 |

| Xerox ColorQube 8570N | Advantec no. 2 filter paper (Advantec MFS) | 100 | 10 min | AutoCAD (Autodesk, Inc.) | Hot plate | 67, 68 |

| Xerox Phaser 8000DP | Whatman no. 114 filter paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 120 | 2 min | … | Oven | 57 |

| Xerox Color Qube 8570 | Whatman no. 1 chromatography paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) | 175 | 50 s | Illustrator (Adobe Systems Inc.) | Hot plate | 69, 70 |

Lu et al.31 fabricated a μPAD using the wax printing method [Fig. 2(b)] and compared the fabrication process of the device with a device patterned with a wax pen and another device patterned with wax on the draft printed by an inkjet printer. The hydrophobic barriers were printed with a 2400 × 2400 dpi wax printer (FUJIXEROX Phaser 8560DN, Japan), and then inserted in an oven for the penetration of the wax through the thickness of the paper to form complete barriers. The oven temperature was chosen as 150 °C to shorten the fabrication time. The wax printing method was relatively very rapid (5–10 min) compared to the two other methods and also repeatable. The results showed that fabricating with a wax printer was easier due to the speed and the resolution of the method. To test the functionality of the μPAD, a multiplex assay (glucose and protein assay) was performed, and different concentration levels of glucose and protein were simultaneously and successfully detected.

In μPAD applications, the Washburn equation is widely used for the capillary motion of the liquid or imbibition of the liquid into the channel or for the spreading of the molten wax in paper. The Washburn equation71 gives the length of a horizontal capillary penetrated by a liquid due to capillary pressure alone [Eq. (1)]. The derivation starts with the Poiseuille's law for the pressure drop in a cylindrical tube and atmospheric and hydrostatic pressures are neglected. The slip coefficient is also neglected as the channel walls are assumed to be fully wetted as Washburn used mercury in the glass tube. Washburn finds

| (1) |

where is the distance traveled by the liquid, and it depends on the surface tension and the viscosity , the time , the capillary radius , and the contact angle . As the same equation was found by Lucas three years earlier,72 the equation is also known as Lucas-Washburn equation. In fact, the relationship of length being proportional to the square root of time was given without the details by Bell and Cameron73 even 12 years earlier. Even though it is known that there are various limitations to the use of Washburn's equation,74 its use in paper microfluidics is usually well accepted. For example, Carrilho et al.30 investigated the spreading mechanism of the wax in paper, the ideal heating mechanism, and the resolution of the wax printing method using the Washburn equation as the motion of the liquid in paper is based on the capillary flow. The spreading distance of the wax through the horizontally printed lines does not depend on the width of the printed hydrophobic barrier and the width of the channel between the two barriers as long as the printed wax is present at sufficient amount.63

It should be noted that when the Washburn equation is used for the spreading of the molten wax, the surface tension and the viscosity are both temperature dependent. Therefore, only at constant and uniform temperature, the wax is expected to spread the same distance from both edges of the printed line. Consequently, after the heating, as the printed lines are spread by 2, the channel will be narrowed by 2 (distance from both edges). The distance was determined to be 275 μm for the printed lines with a width larger than 300 μm. Their observation on the spreading of the wax through the paper was compatible with that expressed by the Washburn equation.

The minimum width of printed lines to form a complete non-leaking channel barrier spreading completely through the thickness of the paper was also investigated.30 The cellulose fibers of the filter paper were claimed to have a single orientation, and affected the spreading distance of the wax. Circle was chosen as the shape to guarantee the spreading of the wax at every possible direction. The minimum line width to have enough amount of wax to form barriers independent of the printed orientation was determined to be 300 μm [Fig. 2(c)].

C. Theoretical and computational approaches

Most of the current theoretical models for liquid imbibition are based on the Washburn equation71 as given in Eq. (1) where the distance travelled by the liquid is proportional to the square root of time. There are also some models for lateral flow assays that include not only the capillary flow in porous medium but also the advection of the analyte and the reactions taking place in the detection zone.75 Earlier models include capillary conduction of liquids derived using Darcy's law and diffusion.76 Darcy's law-based models are also used for the wicking in paper.77 Lately, stating that the tube radius varies slowly along the axis, the lubrication theory is also used to model liquid imbibition.78 To design a paper microfluidic device, both the microscopic scale including the air-liquid curvature and macroscopic scale dictating the capillary filling need to be taken into account.79 There are also some work that deal only with the pumping mechanism made out of paper, i.e., passive pumping.80 The flow in the paper is modeled using radial capillarity.81

Various geometries are studied in the literature. The radial transport of a liquid, i.e., radial capillarity81 on a filter paper from an infinite reservoir is analytically obtained.82 For a rectangular cross-section 2D paper network, Fu et al.83 derived resistances for geometries that include sudden expansions [Fig. 3(a)]. A two-dimensional wet-out model was used on thin nitrocellulose strips expanding to the same constant width at different points. The experimental and computational results showed that the strip having initially a longer thin part was completely wetted in a shorter time. The data obtained from both experiment and simulation matched quantitatively and the shape of the flow demonstrated qualitative similarities. A similar work for more complex geometries was carried out by Shou et al.84 They performed experiments and computations. The imbibition of liquid into fans (rectangle appended to a circular sector) with various angles [Fig. 3(b)] was studied using COMSOL Multiphysics.85 The model was one dimensional for the simple strip and two dimensional for the fan-shaped strip. In the one dimensional model, the dry porous media were modeled as dipping in water. The model assumed instantaneous wetting of the reservoir just after dipping of the media. In both models, the computations stopped working due to the deformation of the mesh after reaching a critical point of minimum quality. In a rectangular-shaped model, the experimental and computational model fitted well on the curve obtained from the Washburn equation. In a fan- shaped model, the results showed that radial flow in a circular zone caused a decrease in the velocity of the fluid coming from the rectangular zone. Elizalde et al.86 determined the radius of the capillary for given as a function of time as in Eq. (1). An open capillary with a U-shape was also studied recently.87 Castro et al.88 included the internal volume changes due to the residual water by adopting the model proposed by Fries et al.89 that incorporates evaporation. A two-dimensional imbibition model of paper networks for various geometries is proposed by solving the nonlinear Richard's equation for unsaturated porous media.90 A hydrophobic top cover is also implemented.91

FIG. 3.

(a) Experimental and computational fluid transport on paper strips. Reprinted with permission from Fu et al., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 10, 29–35 (2011). Copyright 2010 Springer-Verlag. (b) Computational simulation of fluid flow on a fan-shaped nitrocellulose strip. Reprinted with permission from Mendez et al., Langmuir 26, 1380–1385 (2010). Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

There are some studies on the effect of channel boundaries on the imbibition speed, which is not present in the Washburn equation. It is known that the speed is slower for narrow channels. Hong and Kim92 argued that the imbibition speed is affected by the wettability of the channel walls. There are also fewer examples of non-Newtonian capillary flow models performed, e.g., power law model93 and Herschel-Bulkley model.94

III. μPAD APPLICATIONS

A. 3D μPADs for cultivation

After the first proposal of 3D μPADs95 in 2009, Carrilho et al.30 proposed the first 3D device by combining the wax printed layers with a double-sided adhesive tape. The device enabled liquids to flow in lateral and vertical directions without crossing each other and to be distributed into any desired number of detection zones without mixing with each other. As shown in Fig. 4(a), the four individual samples which are dropped on four individual sample zones at the top layer can be distributed into 16 zones (4 for each sample) at the bottom layer. Moreover, the devices may allow 4 different assays for each of the 4 individual samples. Briefly, by using this method, paper devices with any desired number of zones can be fabricated for multiple assays. In another study, Noh and Phillips96 improved 3D μPADs [Fig. 4(b)] by using the same method except that they used an extra paper level containing different concentrations of wax in each circular zone where the sample passed through. That additional layer showed that the time required for the sample to wick the whole 3D path can be controlled since different concentrations of wax on the extra layer result in different delay in flow pass.

FIG. 4.

(a) Presentation of multilayers of a 3D μPAD. Reprinted with permission from Carrilho et al., Anal. Chem. 81, 7091 (2009). Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society. (b) Presentation of a 3D μPAD with an extra paper level containing different concentrations of wax. Reprinted with permission from Noh and Phillips, Anal. Chem. 82, 4181–4187 (2010). Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society. (c) Vertical cross section of a wax-printed channel. Reprinted with permission from Renault et al., Langmuir 30, 7030–7036 (2014). Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society. (d) A 4 × 4 zone plate for cell growth. Reprinted with permission from Schonhorn et al., Lab Chip 14, 4653–4658 (2014). Copyright 2014 The Royal Society of Chemistry. (e) Layers of a 3D μPAD for E. coli and phage M13 growth. Reprinted with permission from Tao et al., BioChip J. 9, 97–104 (2015). Copyright 2015 The Korean BioChip Society and Springer.

In 3D μPADs, the presence of vertical layers shortens the fluidic pathway to be wetted by the liquids; therefore, a 3D device requires a smaller sample volume for a paper-based diagnostic test compared to the conventional lateral flow devices. Furthermore, using adhesive tapes has advantages of having easily and manually patterned holes and being removable to separate each paper layer.60

Wax transportation makes new functional channels possible for complex fluid systems in μPADs. By adjusting the amount of initial wax on the paper, the thickness of the paper may not be completely penetrated by the wax. Therefore, more functional channels may be generated. Hemi-channels or fully enclosed channels were fabricated rather than ordinary open channels by changing the design of printed lines on the filter paper [Fig. 4(c)].63 Any possible cross reactivity of liquids, flowing in hemi or fully enclosed channels, were precluded without any need to an adhesive tape layer as in the case of open channels. The reason was that one side of the printed hemi-channels and both sides of the fully enclosed channels, which were covered with wax, blocked fluids to flow into the next layer of channels. In another work,97 while printing both sides of the paper, double sided printing and lamination are employed together. By controlling the lamination process, the printed wax reaches a height smaller than the thickness of the single sheet of paper. Therefore, the spreading of the wax is controlled to create more complex geometries. That design provided less complexity for building 3D μPADs, and reduced water evaporation compared to the design of 3D μPADs with fully open channels. On the other hand, besides the amount of water evaporation, there are various other parameters due to the detection technique and the function of the wax-printed channels. For instance, the design of a 3D μPAD was investigated by considering the two correlations of the channel length with assay time and electrochemical (EC) signal intensity.61 In order to optimize the lateral channel length, an immunoassay of human chorionic gonadotropin was tested on the wax patterned 3D paper devices with channel length, varying from 2 to 10 mm. The results indicated a positive linear relationship of assay duration with the channel length and the device with no lateral channel (flow only in the vertical direction) resulted in the shortest assay duration. On the other hand, the signal quality was reduced with decreasing channel length and the signal obtained from the assay on the device with no lateral channel was low. Despite the fact that the assay time is a significant parameter for the sample size and the cost of the device, the sensitivity of the device is essential for the early diagnosis. Therefore, based on the observations, the optimum channel length was found to be 6 mm.

The paper layers may be analyzed separately for certain applications such as cells in gels in paper–CIGIP, a paper-based 3D device fabricated by Derda et al.33 They combined 8 layers of paper with 96 chambers whose boundaries are made of wax, for investigating the cell behavior by changing and controlling “gradient” in the concentration of molecules such as oxygen and other nutrients. In order to examine the 3D cell proliferation in vitro, each layer of paper was considered as the levels in the 3rd dimension, and was monitored independently by separating each layer after the cell growth. As a result, de-stacking of each layer provided easy examination of gradual change in cell growth in 3D vitro models. By this method, it was possible to obtain an effective and multipurpose system to investigate 3D cell proliferation. The suitability of paper-based microfluidic systems for cell-based assays in many fields (e.g., drug screening or quantitative cell-biology) was checked by investigating cell proliferation and chemosensitivity.62 In order to observe the in vivo cell-behavior, a 3D structured paper-based device was fabricated using the wax-printing method. The conventional 2D settings such as Petri-dish and multi-well microplate do not represent the cell response well enough, since the cells survive essentially in 3D environments. First, the cyto-compatibility of filter paper with varying amounts of printed wax was examined. The amount of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), the indicator of cyto-compatibility, was analyzed by performing conventional WST-1 assay. The results showed that the LDH level was constant, so that the wax was not toxic for the cell culture. Then, the results obtained from SEM micrographs demonstrated that the cells were successfully grown in each direction including the depth (the thickness of the paper). This is the main advantage of the present paper-based platform compared to the other 2D models where the cell growth occurs only laterally. In that novel platform, the cell growth showed a similar behavior to that obtained by the methylcellulose (MC) hydrogel technique, a conventional 3D method. In the same work,62 another 3D device consisting of several layers of 4 × 4 wax-patterned zones was also designed for investigating the chemosensitivity of cancer cells against anti-cancer drugs. Depending on the distance of the cell culture zones, the effect of anti-cancer drugs differed in terms of cell death and the continuation of cell growth. As shown in Fig. 4(d), at the first two columns, which are closer to the side, where the drugs were applied, the programmed cell death occurred on the contrary of the next two columns, where the cell proliferation continued. That work showed that a 3D paper-based microfluidic system is suitable for cell-based assay.

A paper-based device consisting of wax-printed chambers and a glass substrate with bilateral electrodes was proposed for the impedimetric quantification of the cells.67 The cells were encapsulated in hydrogel for three-dimensional cell growth. The number of cells was quantified by measuring the impedance. The aim of the study was to characterize the cell growth and to check the consistency of the results with conventional assay (WST-1). First, the parameters such as the initial cell number and the impedance measurement frequency were investigated for their eligibility in further assays. The optimum measurement frequency was determined to be 100 Hz due to the relationship between the cell number and the impedance magnitude. Then, the optimum initial cell number was determined to be 5000 due to the linearity between the color intensity and the cell number. The results of the assay, performed with optimum initial cell number and frequency, showed that impedimetric quantification of the cells in the paper-based device was non-invasive and matched with those of the conventional assay results. A multilayer device combining the wax-patterned paper and a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane was designed and fabricated for bacteria growth.57 The hydrophobic barriers of growth zones for bacteria were created by using the wax printing method, and the PDMS membrane was used to prohibit water evaporation, but allowed oxygen passage [Fig. 4(e)]. The device was tested by investigating the growth rate of Escherichia coli (E. coli) and phage M13, and the results were compared with the growth rates on agar plates as well as in shaking cultures by using the plaque or colony forming assays. The rate of growth was observed to be similar in all cases. Consequently, the device may substitute the conventional techniques as it is easier and more rapid. Furthermore, to show that these devices can be used in developing countries where automated equipment for cell-based diagnosis is not available, the whole device was fabricated by high school students who do not possess any special skills.

B. μPADs designed for detection and analysis

Wax printed μPADs are generally employed in the medical diagnostic processes and aimed to be commercially available in the near future, especially in the developing countries. A summary of immunoassay based μPADs is given in Table II. There are also μPADs designed for the analysis of certain chemicals98–100 (e.g., explosives, synthetic compounds, pharmaceuticals, and organic molecules), the detection of microorganisms in environmental resources,101 blood typing,66 hepatoxicity,65 acid-base titration,102 infection detection,103 and nucleic acid detection.69,104 μPADs can also be used for the multiple detection of metals such as nickel, copper, iron, cadmium, chromium, or lead.105,106

TABLE II.

Immunoassay based μPads.

| Assay | Detection Technique | Platform | Samples | Detected | Antibodies | Sample Size | Analyse Time | Sensitivity | Related diseases or diagnosis | Reference number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-ELISA | Colorimetric intensity | Chamber | E. coli DH-5α cell concentration | Anti E-coli antibody as the primary antibody (primary) HRP-conjugated streptavidin(secondary) | 200-μl (109 cells/ml) | 5 h | 105 CFUs/ml | Urinary tract infections | 120 | |

| p-ELISA | Colorimetric intensity | 96-well plate | Human saliva | NPY antigen concentration | Goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (primary) Mouse anti-human neuropeptide Y monoclonal antibody (secondary) | 3 μl | <1 h | ∼2.3 nM (NBT/BCIP (substrate)) 4.0 nM (pNPP (substrate)) | Traumatic brain injury Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | 121 |

| p-ELISA | Colorimetric intensity | Chamber | … | Human IgG concentration | Gold nanoparticle labeled antihuman IgG | 2 μl | … | … | … | 34 |

| p-ELISA | Colorimetric intensity | 3D-μPad | Rabbit serum | hepatitis B surface antigen concentration | - (primary) ALP-conjugated antibody (secondary) | 2 μl | 43 min | 330 pM | Hepatitis B | 122 |

| p-ELISA | Colorimetric intensity | 96-well plate | Aqueous humor | The vascular endothelial growth factor protein antigen concentration | HRP conjugated Avastin (bevacizumab) | 2 μl | 44 min | 33.7 fg/ml | Proliferative diabetic retinopathy Age-related macular degeneration Retinal vein occlusion | 123 |

| p-ELISA | Colorimetric intensity | 96-well plate | Serum and blister fluid | Noncollagenous 16A antigen concentration | Anti-NC16A autoimmune antibody (primary) HRP conjugated polyclonal rabbit antihuman IgG (secondary) | 2 μl | 70 min | 81.8% (serum) 83.3 (blister fluid) | Bullous pemphigoid | 124 |

| p-ELISA | Colorimetric intensity | 96-well plate | Aqueous humor | The vascular endothelial growth factor protein antigen concentration | HRP conjugated Avastin (bevacizumab) | 2 μl | 45 min | 33.7 fg/ml | Age-related macular degeneration Retinal vein occlusion | 125 |

| p-ELISA | Colorimetric intensity | 96-well plate | Human serum | HIV-1 envelope antigen gp41 concentration | Anti-human IgG antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | 3 μl | … | … | HIV | 59 |

| Label-free photoelectrochemical immunoassay | Photoelectrochemical signal | μPad | Human serum | CEA concentration | CEA capture antibody | 5 μl | … | 0.28 pg/ml | Tumor diseases | 126 |

| Fluoroimmunoassay (FIA) | Fluorescence Intensity | Chamber | … | Human IgG concentration | FITC-labeled antihuman IgG | 2 μl | … | … | … | 34 |

| Enzyme-free immunoassay | Colorimetric intensity | 3D-μPad | Urine | human chorionic gonadotropin concentration | Antibody labeled with colloidal gold | 20 μl | 10 min | 6.7 mIU/ml | Pregnancy | 61 |

| Enzyme-free immunoassay | Colorimetric intensity | 48-well plate | Cell lysate and clinical samples | Outer surface glycoproteins of H1N1 and H3N2 virus | Rabbit anti-NP antibody (capture) Monoclonal mouse anti-H1 and monoclonal mouse anti-H3 antibodies (primary) Anti-mouse IgG-gold nanoparticles conjugate and anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (secondary) | 5 μL | <1 h | 2.7 × 103 pfu/assay 2.7 × 104 pfu/assay (respectively) | Epidemics Respiratory illness | 68 |

| ECLIA | Electrochemiluminescence intensity | μ μPAD | Human serum | AFP concentration | Monoclonal AFP antibody (primary) Anti-AFP antibody conjugated with MWCNTs/N-GQDs (secondary) | 20 μl | … | 1.2 pg/ml | Tumor diseases | 127 |

| ECLIA | Electrochemiluminescence intensity | 3D-μPAD | Human serum | CEA concentration | Mouse monoclonal CEA capture antibody (primary) [Ru(bpy)3]2+-labeled signal CEA antibody (secondary) | 2 μl | … | 0.001 ng/ml (human CEA standard solution) 0.008 ng/ml (human control serum sample) | Tumor diseases | 128 |

| ECLIA | Electrochemiluminescence intensity | μPAD | Human serum | AFP, CA199, CA153 and CEA concentration | Mouse monoclonal AFP, CA153, CA199 and CEA capture antibodies (primary) CND or Ru(bpy)32+ labeled mouse monoclonal AFP, CA153, CA199 and CEA signal antibodies (secondary) | 4 μl | 15 min | 0.02 ng/ml, 6.0 mU/ml, 5.0 mU/ml, 4.0 pg/ml (respectively) | Tumor diseases | 129 |

| ECLIA | Electrochemiluminescence intensity | origami-based μPAD | Human serum | CEA concentration | Mouse monoclonal CEA capture antibodies (primary) Anti-CEA/QDs/NPs bioconjugate (secondary) | 5 μl | … | 0.12 pg/ml | Tumor diseases | 130 |

| ECLIA | Electrochemiluminescence intensity | 3D-μPAD | Human serum | AFP, CA125, CA199 and CEA concentration | AFP, CA125, CA199 and CEA capture antibodies (primary) Ru(bpy)32+-labeled signal AFP, CA125, CA199 and CEA antibodies (secondary) | 2 μl | … | 0.15 ng/ml, 0.6 U/ml, 0.17 U/ml, 0.5 ng/ml (respectively) | Tumor diseases | 131 |

| ECIA | Electrochemical signal | 8-well plate | Mouse serum | HIV p24 core antigen and HCV core antigen concentration | HIV or HCV antibody (primary) Goat anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (secondary) | 4 μl | 20 min | 300 pg/ml, 750 pg/ml (respectively) | HIV/HCV co-infection | 132 |

| ECIA | Electrochemical signal | 3D-μPAD | Human serum | CA125 and CEA concentration | Mouse monoclonal capture CA125 and CEA antibodies (primary) HRP labeled CA125 and CEA signal antibody (secondary) | 2 μl | … | 0.2 mU/ml, 0.01 ng/ml (respectively) | Tumor diseases | 133 |

| ECIA | Electrochemical signal | origami-based μPAD | Human serum | AFP and CEA concentration | Monoclonal CEA and AFP antibodies (primary) Anti-AFP/3DGS@Fc-COOH and anti-CEA/3DGS@MB (secondary) | … | … | 0.8 pg/ml, 0.5 pg/ml (respectively) | Tumor diseases | 134 |

| ECIA | Electrochemical signal | origami-based μPAD | Water sample | Microcystin-LR concentration | Propargyl functionalized anti-Microcystin-LR antibody (primary) HRP conjugated anti-Microcystin-LR antibody on Fe3O4@SiO2 | … | … | 0.004 μg/ml | Liver damage Gastroenteritis Stop breathing episodes | 135 |

| EC | Electrochemical signal | μPAD | Human serum | PSA concentration | Anti-PSA antibody (primary) HRP labeled anti-PSA antibody (secondary) | 10 μl | … | 0.46 pg/ml | Tumor diseases | 136 |

| CLIA | Chemiluminescence intensity | origami-based μPAD | Whole blood sample | AFP, CA153, CA199 and CEA concentration | AFP, CA153, CA199 and CEA capture antibodies (primary) Non-labeled signal AFP, CA153, CA199 and CEA antibodies (secondary) | 5 μL | 16 min | 1.0 ng/ml, 0.4 U/ml, 0.06 U/ml, 0.02 ng/ml (respectively) | Tumor diseases | 137 |

A simple wax-printed device consisting of 5 detection zones and a sample zone [Fig. 5(a)] was developed for the detection of military and improvised explosives.64 One of the devices was designed for explosive samples of inorganic pyrotechnic compositions such as ammonium, nitrate, nitrite, chlorate, and perchlorate, and the other one was designed to detect organic explosives such as RDX/HMX/PETN, military explosives (TNT, TNB, tetryl), urea nitrate, nitrate, and hydrogen peroxide. The detection method was colorimetric, so that the test zones dedicated to specific explosives were turned into different colors in the presence of that explosive in the sample solution. When more than one of the explosives mentioned above were present, it was possible to detect each one simultaneously. In the fabrication process, the color of the ink was chosen as blue since none of the explosives was expected to turn blue and the white colored wax was not chosen due to a possible lack of contrast with the white color of the paper. During the preparation of the assay for organic explosives, the optimum concentration of acid solution was determined since the high acidic solution, which is required in the conventional colorimetric detection of organic explosives, damages the structure of the paper. The whole process was completed in 5 min and the detection limits were observed in a wide range such as 0.39–19.8 μg of chemical. Like explosives, halide ions and heavy metals can also be detected by using a paper-based analytical device. A μPAD was used for the detection of Pb+2 ions as heavy metal, picric acid as an explosive, and chloride as a halide ion.107 In this work, standard office paper was wax printed to be the platform for the electrochemical detection. Silver ink was used for the electrochemical cells and connected to a potentiostat. Apart from the toxic compounds, μPADs can be employed for the detection of narcotic drugs by measuring the concentration of additives or active substances.108

FIG. 5.

(a) μPAD for the detection of chemical explosives. Reprinted with permission from Peters et al., Anal. Methods 7, 63–70 (2015). Copyright 2015 The Royal Society of Chemistry. (b) A blood typing device fabricated by wax-printing. Reprinted with permission from Noiphung et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 67, 485–489 (2015). Copyright 2015 Elsevier B.V. (c) A device with 5 zones for AST and ALT testing. Reprinted with permission from Pollock et al., Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 152ra129 (2012). Copyright 2012 American Association for the Advancement of Science.

μPADs are widely used in biological analyses. For instance, male fertility can be quantified on a wax-printed device by detecting live and motile sperm concentrations.109 Furthermore, the concentrations of lactate dehydrogenase, which is a biomarker of cancer and organ failure,110 and acetylcholinesterase, which is the enzyme responsible for the breakdown of neurotransmitters associated with Alzheimer,111 were detected. A simple wax-printed μPAD can detect glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, which is critical during malaria treatment since it may result in haemolytic crisis.112 Moreover, a μPAD fabricated by the wax printing method was used for measuring the concentration of nitrite in saliva. The concentration of nitrite is an indicator of the periodontitis which is an oral disease and the periodontitis may result in abscess and infection around the surrounding tissues of teeth.113

It is highly important to detect hepatoxicity (drug induced liver injury) early and rapidly since drug usage during the treatment of tuberculosis or HIV may result in hepatoxicity in certain cases. An increase in Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels may indicate hepatoxicity. Therefore, a μPAD was fabricated enabling semi-quantitative blood tests for colorimetric assay to detect AST and ALT in blood or serum samples [Fig. 5(c)].65 The device had a three-dimensional structure and functionality, and allowed samples to flow through each layer and it was capable of distributing samples from one channel into multiple channels through the layers of paper and to arrange the direction of flow in these multiple channels due to the design of the paper-based device. All of these operations made multiple parallel assays possible and prevented cross-reactivity between the assays. The minimum amount of sample to completely wick the channels and the zones and to give sufficient color change was determined to be 25 μl. The performance of the device was compared with that of a gold-standard automated test by using a Bland–Altman plot. The assay took 15 min and the results showed that the device reliably measured transaminase (AST and ALT). However, pyruvic acid and ascorbic acid affected ALT assay, but not on a large scale. When pyruvate concentration exceeded 0.2 mM, ALT assay might give false results. Furthermore, blood samples, waited for more than six hours before testing, resulted in high ALT values due to pyruvate forming from lactate which was released by red blood cells. A μPAD combined with a blood separation membrane was proposed to detect both Rh and ABO blood groups simultaneously.66 This device was fabricated using the wax printing method for the channels and the wax dipping method for the blood separation. The latter method is based on dipping the paper into a beaker of melted wax and then cooling of the wax. As presented in Fig. 5(b), the device was composed of two sides: (1) Forward side, where samples, diluted at a ratio of 1:2, were applied for the detection of Rh and ABO blood type, and (2) Reverse side, where plasma was separated from the 90 μl of whole blood samples and reacted with added A-cell or B-cell suspensions for anti-typing. The main conventional methods are tube and slide test techniques, which require many steps and result in detection of low sensitivity. Although the assay time for the slide technique is less than that for the proposed paper-based method, the proposed technique did not require any additional confirmation for the reverse ABO grouping, and it was easy and cheap, which are the desired characteristics of a test in rural areas and in developing countries. Furthermore, another conventional technique called gel test, which is a biosafe method, requires less sample volume, needs additional incubation and centrifugation steps; hence, longer time. The results obtained with real blood samples showed that the device worked with 100% accuracy. Furthermore, the duration of the assay was 10 min; the μPad with already absorbed antibodies could be stored for 7 days at room temperature and 21 days at 4 °C. Another μPAD was employed also for forward and reverse ABO blood group typing with visual detection based on the distance covered by a blood sample of 20 μl.114

For the colorimetric detection of tuberculosis using unmodified gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), a μPAD was fabricated.115 The detection mechanism was based on the aggregation of unmodified AuNPs. In the presence of the target ssDNA sequence (2.6 nM Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex), AuNP aggregation occurred in the solution containing sodium chloride and induced a color change (red to blue) in AuNP colloids. The dissociation of salt ions prevented the aggregation. The results showed that the μPAD worked successfully for the detection of tuberculosis in 1 h after the DNA extraction step. The proposed detection mechanism on the device was simple and time-efficient relative to the conventional techniques, which may require several hours and complex equipment. Apart from the colorimetric detection, wax printed papers can be connected to an electrochemical sensor for electrochemical detection of biological substitutes such as ethanol,116 glucose,117 and cholesterol.118 Moreover, there are μPADs that use electrochemiluminescence detection methods for chemical and biological analyses.119

1. μPADs for colorimetric paper-based enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (p-ELISA) devices

A p-ELISA was developed in a 96-well paper-based platform fabricated by wax printing.59 The sensitivity, operation time, and reagent requirements of that new paper-based platform were compared to those of the indirect ELISA by detecting the HIV-1 envelope antigen gp41 in human serum. Rapidly quantified results were obtained with a colorimetric readout, which did not require any expensive plate reader. Even though the sensitivity of the assay was almost 15 times lower than that of the conventional ELISA, the whole process took less than an hour and required a very small volume of sample (3 μl of human serum) and reagents (14 μl of total reagents), which are almost one twenty fifth used in the conventional ELISA. Therefore, it is still a promising technology for the future POC diagnostic analysis; especially in developing countries, where resources are limited. Being faster and less expensive and not requiring any complex equipment, p-ELISA is a great alternative to the conventional ELISA. The sensitivity of the method was increased in subsequent studies. Another 96-well paper-based device was produced to investigate the concentration of neuropeptide Y (NPY), an indicator of stress resilience, in human serum and in deionized (DI) water.121 A high level of NPY signifies high mental endurance to stress, while a low level of NPY refers to possible psychological problems. The NPY level may also point out traumatic brain injury and its level provides significant information for the early diagnosis and the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. In order to detect the alkaline phosphatase conjugated NPY antibody, the p-ELISA test was applied. High sensitivity was achieved and the limit of detection values in the assays were relatively close to those obtained by conventional methods. The colorimetric results were recorded by a digital camera, and quantified by image analysis, in which a new method called delta RGB was used instead of grayscale images. The results showed that complex biological samples of low limit of detection (LOD) are suitable for p-ELISA tests.

p-ELISA was also applied for the determination of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) level in aqueous humor, which may demonstrate the three ocular diseases such as proliferative diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and retinal vein occlusion.123 A paper-based 96-well plate was fabricated by the wax-printing method, in order to perform this colorimetric semi-quantitative assay. The color intensity was quantified by a calibration curve of various VEGF levels. Only 2 μl aqueous sample was collected from each patient in order to carry out the p-ELISA, whereas the conventional ELISA techniques may require 50 times larger volume of aqueous samples. Since the anterior chamber of the eye allows only 200 μl of aqueous sample before it collapses, p-ELISA techniques suggested in this study are further away from being invasive compared to the conventional ELISA. Furthermore, the sensitivity of the results of p-ELISA is also 150 times better, and the whole testing process takes 5 times less than the conventional ELISA. Monitoring the VEGF level enables an early detection of possible AMD and diabetic retinopathy, rendering an early anti-VEGF treatment possible. An increase in the VEGF levels can be observed by p-ELISA in 16 days before the structural change in the eye, which is detected by fluorescence angiography and optical coherence tomography. This period of time may become longer for conventional ELISA and other conventional point of care POC diagnostic techniques since a slight increase in the VEGF level cannot be detected as sensitively as it can be done by p-ELISA. Also, conventional ELISA gives the results in 4 to 5 days. Therefore even an early detection is achieved, patients should wait a bit longer for the treatment.125 A colorimetric quantitative, sensitive, 96-well plate patterned paper-based ELISA is proposed for rapid diagnosis of autoimmune blistering disease.124 Bullous pemphigoid (BP) has a high mortality rate for patients. The assay was carried out by detecting anti-NC16A autoimmune antibodies in small sizes of both serum and blaster fluid which were taken from both patients and healthy people. The duration of the assay was shorter than that of the conventional method; however, the results were not correlated with the BP Disease Area Index due to limited number of cases.

Another 96 well paper-based platform was developed in order to perform two different ELISA for diagnosing serotype-2 dengue fever.138 Dengue fever is an arboviral infection spread by mosquitoes of the Aedes type found in tropical and subtropical regions and it is endemic in more than 100 countries.139 A p-ELISA was prepared for the detection of dengue virus serotype-2 nonstructural protein-1 antigens both in human serum and buffer systems, and the performance of the device was compared to that of both a LFA device and the conventional ELISA. The nonstructural protein-1 antigens, which are the biomarkers of the dengue virus infection, can be present in human serum at the early stage of the infection. For p-ELISA, the whole process took less than 1 h, the test required a small size of sample and low cost and the sensitivity of this p-ELISA was observed as 40 times higher than that of the conventional one. Furthermore, it has been also reported that not only the nonstructural protein-1, but also serotype-2 envelope proteins could be detected by this method. A paper-based one chamber platform with wax printed hydrophobic walls was fabricated for the in vitro detection of E. coli for the urinary tract infections, which are common in women. p-ELISA was able to detect E. coli clone up to 105 CFUs/ml in 5 h. This novel platform may allow early diagnosis, on the contrary to the conventional methods, which require 3–5 days of cell cultivation. Early diagnosis of E. coli is significant in the case of sepsis that may result in death if not timely treated.120

2. μPADs for electrochemical immunoassay (ECIA) devices

The electrochemical (EC) immunosensing mechanisms integrated with the wax-printed paper were proposed as an alternative advanced technology. An EC immunoassay on μPADs was first reported in 2012.133 A microfluidic paper-based 3D (ECIA) device was fabricated to detect two tumor markers, Carcino antigen 125 (CA125) and Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), in real human serum samples. The electrodes were screen printed on a transparent polyethylene terephthalate substrate and combined with wax-printed paper cells. In order to increase the assay efficiency, the electronic conductivity of the EC cells and the antibody stabilization were increased by modifying the paper with multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). The MWCNT modified cellulose fibers have the advantage of fast immunoreaction due to paper's loose porous structure, which allows easy access of the biomolecules. The results showed that the LOD value of the assay was lower than that obtained by the conventional methods. Furthermore, the incubation time was optimized to perform rapid and sensitive analysis, and the device was suitable for regeneration and reuse. There are also some works that addressed a few cancer biomarkers and mainly improved sensing mechanisms with new protocols. Another kind of EC immunodevice, a 3D origami-based electrochemical device (3D-OECD) was designed and fabricated by folding the wax-printed paper as origami in order to provide a vertical flow.140 These devices used different dual-signal amplification techniques in order to obtain high sensitivity and they were proposed for the specific and highly sensitive detection of CA125 and Carcinoma antigen 199 (CA199). The sensing mechanism was improved by the growth of cuboid silver on the paper working electrode (PWE) and the labeling of signal antibody with metal ion coated nanoporous silver–chitosan. For the detection of CA125, NSC was coated with gold ions, whereas for CA199, it was coated with cadmium ions. Three other dual-signal amplification techniques were proposed for the specific and highly sensitive detection on 3D-OECD. The amplification techniques were based on (i) the growth of Au@Pd alloy nanoparticles on the PWE and the attachment of methylene blue (MB)/Au@Pt hybrids to mouse monoclonal signal antibody (McAb2),141 (ii) the growth of polyaniline-AuNPs on the PWE and the labeling of signal antibody with redox probes [Methylene blue (MB) and carboxyl ferrocene (Fc-COOH)] on the 3D graphene sheets (GSs)134 [Fig. 6(a)] and (iii) the growth of the gold nanorod (AuNR) layer on the PWE and the labeling of signal antibody with metal ion coated gold(Au)/BSA.142 The pH of the detection solutions and the incubation times were optimized to get a maximum signal. The resulting signals of the assays performed with real human serum samples were compatible with those obtained by a commercial EC test for each work.

FIG. 6.

(a) PWE modified μPAD fabricated by wax printing for tumor biomarker detection. Reprinted with permission from Li et al., Electrochim. Acta 120, 102–109 (2014). Copyright 2014 Elsevier Ltd. (b) Electrochemical 3D μPAD consisting of two wax printed layers modified with electrodes for detection of tumor biomarker. Reprinted with permission from Li et al., Sens. Actuators, B 202, 314–322 (2014). Copyright 2014 Elsevier B.V. (c) Two wax printed layers of a μPAD modified with electrodes. Reprinted with permission from Ge et al., Biomaterials 33, 1024–1031 (2012). Copyright 2011 Elsevier Ltd.

Another EC immunosensor was designed based on the electrodeposition of MnO2 nanowires, on the sequentially grown AuNPs in the screen-printed electrode.143 The sensing mechanism was integrated to an origami based device. In order to amplify the EC signal coming from the prostate specific antigen (PSA) (a biomarker of prostatic cancer), the second antibody was labeled with Carbon Nanospheres-Glucose Oxidase instead of ligand conjugated natural enzyme. The utilization of carbon nanospheres resulted in a high surface to volume ratio, which refers to a high number of immobilized biomolecules, and displayed high sensitivity. The limits of the detection of this novel method were comparable with those of the conventional commercial method. EC immunosensor based screen-printed electrodes were fabricated on a vegetable parchment and integrated to wax printed microchannels.136 In order to obtain high sensitivity and conductivity, the graphene nanosheets and HRP labeled signal antibody with gold nano particles were used for the detection of PSA. The limit of detection for PSA was found to be 0.46 pg/ml.

For the specific and sensitive detection of Microcystin (MC)-LR in the water supplies, an origami EC immunoassay-device was designed based on the PWE with a AuNP layer.135 MC-LR is produced by cyanobacteria. It is highly toxic and threatens human health possibly causing severe liver damage and gastroenteritis and stops breathing. Before the preparation of the immunoassay, the signal antibody was conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and Magnetic silica nanoparticles (MSNs), which displayed a higher response and sensitivity in assays. The quantification of the MC-LR level was achieved at a relatively sufficient sensitivity and specificity level. Recently, high accuracy and sensitivity were achieved with a paper-based EC device for diagnosing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infection by EC immunoassay.132 A portable potentiostat adapted to an EC microfluidic paper-based immunosensor array enabled the detection of signals from the EC reaction. This platform required 3 μl sample and performed the test in 20 min. Another advantage of that platform was to transmit data to a healthcare institution by a Bluetooth connection.

3. μPADs with electrochemiluminescence (ECL) detection - electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) devices

In 2012, an ECL detection mechanism on μPADs was developed by Yan et al. for the first time.128 The main aim was to improve the sensitivity in 3D paper-based immunodevices for the detection of cancer bio-markers. The sensitivity was enhanced by a signal amplification method. Additionally, the reproducibility of the immunodevice, the optimum pH value, the optimum sample volume, and the optimum duration of the incubation process were investigated. The ECLIA was performed for the detection of CEA concentration in real human serum, which is critical for the diagnosis of many cancer types such as breast cancer, cervical carcinoma, intestinal cancer, and esophagus cancer. The device was built with two layers of cellulose paper, which were wax printed to form hydrophobic barriers. Then, the reference and carbon working electrodes were screen-printed one by one on these to paper layers. The three-dimensional device was able to detect signals from the ECL immunoreactions by using tris-(bipyridine)-ruthenium(II)/tri-n-propylamine (Ru(bpy)32+/TPrA) ECL system. To replicate the experiments, a more uniform structure of the paper-electrode was obtained by coating it with chitosan film. In another work,129 the device was further improved for the simultaneous detection of four cancer biomarkers. That novel device had two reaction zones, and each zone allowed detection of two of the four samples. Each of the two immunocomplexes in one zone could be labeled with Ru(bpy)32+/TPrA or Carbon nanodots (CNDs)/K2S2O8 since these two different ECL systems on each zone generated an ECL signal at different constant potentials (positive or negative). The optimum potential values to clearly observe the ECL were determined to be 1.2 V for Ru(bpy)32+ labeled immunocomplexes (in the presence of TPrA) and −1.2 V for CND labeled immunocomplexes (in the presence of K2S2O8). At 1.2 V of constant potential, only Ru(bpy)32+ labeled Ab2 and at −1.2 V of constant potential, only CNDs emitted the ECL signal. For that reason, the device was able to detect simultaneously the four antigen types. Furthermore, no cross reactivity was observed, and the device showed good stability for 6–8 weeks of storage. The results of the assay performed on the device were very similar to those obtained by the conventional methods, and the limits of the detection for four markers were lower than the cutoff values.

An ECLIA device was prepared by combining a wax printed 3D origami device with an ECL immunosensor for the detection of CEA in real human serum samples.130 In order to achieve high sensitivity, the immunosensor was fabricated based on the growth of porous silver nanoparticles on the PWE and signal amplification label. The PWE was modified with porous silver nanoparticles because of the high conductivity, large surface area, and strong adsorption of Ag nanoparticles. The amplification technique was based on the substitution of a single signal label of CdTe quantum dots with an amplified signal due to a large number of nanoporous silver functionalized with CdTe quantum dots labels. The results were compatible with the values obtained from a commercial ECL test, and the LOD of CEA was found to be 0.12 pg/ml with a linear range of 0.5 pg/ml to 20 ng/ml. Furthermore, the device showed very stable performance for 15 days of storage and high specificity. Another ECL immunosensor for the highly sensitive detection of CEA was prepared from a 3D origami device.144 the PWE was modified with nanoporous gold/chitosan, and graphene quantum dot functionalized Au@Pt coreshell nanoparticles were used as the signal label [Fig. 6(b)]. Nanoporous gold/chitosan (NGC) as the sensor platform has the advantages of great biocompatibility and high stability. Additionally, high electrical conductivity of Au@Pt positively affects the sensitivity of the device, where ECL signals of graphene quantum dots are not high. The LOD of CEA was found to be 0.6 pg/ml, which is relatively very low compared to that of conventional methods. The results obtained from tests with real human serum samples were compatible with those obtained by the current conventional methods. Moreover, the device provided good stability and reproducibility. A paper-based ECL device was further proposed for the simultaneous and highly sensitive detection of PSA and CEA.145 The immunoassay was based on the dual signal amplification method, which depends on the usage of 4,4′-(2,5-Dimethoxy-1,4-phenylene)bis(ethyne-2,1-diyl)dibenzoic acid (p-acid) functionalized with nanoporous silver as the ECL label in the presence of TpRA and the graphene oxide-chitosan/gold nanoparticle based platform. The application of graphene oxide and the p-acid during the preparation of the device provided more sensitive detection than that in the case of their absence. Graphene oxide supplies a larger surface area to capture antibodies, higher conductivity, long-term stability, and biocompatibility. Additionally, gold nanoparticles are biocompatible and can be easily functionalized with proteins. The performed assay with real human serum showed that the results were comparable with those obtained by conventional methods, and the limit of detections for PSA and CEA were found to be 1 pg/ml and 0.8 pg/ml, respectively, which were lower than those achieved in the previous paper-based ECL immunoassays and the conventional methods. Furthermore, the multiplexity of the assay was investigated and no cross-reactivity and crosstalk were observed. A 3D paper-based ECL device was fabricated for the detection of four tumor markers, r-fetoprotein, CA125, CA199, and CEA [Fig. 6(c)].131 The same assay procedure in their previous work128 was performed using real human serum samples. In this assay, the optimum sample size was also determined by investigating the uniform immobilization of FITC-labeled CA125 antibodies in the fluorescence images of the paper. The LOD of the four tumor markers was lower than those obtained from conventional methods and the results were comparable with those of conventional ones.

A paper-based electrochemiluminescence device was developed for the highly sensitive detection of α-fetoprotein.127 Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots were used as ECL labels, and paper was modified with gold nanoflowers based on the growth of an interconnected gold nanoflower layer. Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots have the advantages of biocompatibility, high fluorescence activity, and great photostability, making them perfect ECL labels. Moreover, the modification of the PWE with AUNFs provided enhanced conductivity and more effective surface area. That novel ECL strategy resulted in high sensitivity and long-term stability. The LOD was found to be 1.2 pg/ml, which is 2000-fold lower than that of the conventional method; and the results were compatible with the values obtained with conventional tests.

The fabrication process of the devices which allow complex detection mechanisms such as ECL analysis might require more complex equipment and the preparation of assay may take a long time. For instance, the fabrication process requires very complex steps on a paper-based device with the PWE, which is modified with Ag nanosphere particles to get ultrasensitive detection.146 Another process used in the preparation of the device and the assay is the physical or chemical treatment of the paper surface. The treatment provides a better immobilization of the antibodies since the bond between the antibodies and the paper is not strong enough for the antibodies to stay on and not to be washed away. For example, the paper fibers were modified by chitosan in chemiluminescent ELISA.147

IV. ADVANTAGES AND LIMITATIONS OF WAX-PRINTED μPADs

The wax-printed paper-based microfluidic devices have great potential for playing a part in the future diagnostic industry since they possess the existing advantages of μPADs. An important one is that the sample volume in microliters is sufficient to perform a test on these devices with multiple detection zones for multiple assays. Moreover, wax printing technology is very rapid, low-cost, and suitable for mass production since it is possible to print millions of devices in less than a minute with today's technology. Furthermore, the most important advantage is that both the fabrication and the assay processes do not require complex equipment and a facility such as a well-equipped laboratory or a clean room. Consequently, the accessibility of people, who may get infectious diseases such as malaria, HIV or cancer, to diagnostic tests may become easier in near future. These devices may be the solution for early diagnosis and treatment of even ongoing reported situations in rural and remote areas without wasting time in clinical and laboratory analyses.

The colorimetric detection on paper-based devices is easy since the detection equipment includes only a commercial scanner or a smartphone. Moreover, smartphones can easily be used for the purpose of determining the concentration of the target molecule via a basic image processing application. For instance, a smartphone application was designed in order to detect and display the concentration of target bacteria, and the whole process took only seconds.148 Furthermore, a portable device consisting of led lights, a color sensor chip, and a battery was fabricated for colorimetric quantitative detection of protein, nitrite, and iron. The colorimetric detection by the device was based on measuring the light reflectance using a software written in C language. That portable device which costs less than $20 is promising for the biodiagnosis and the detection of environmental pollutants.149

Many researchers have been working on the fabrication of paper-based devices for diagnosis using various techniques, and their primary motivation is to achieve ASSURED criteria. Being one of the promising fabrication techniques, the wax printing is getting more preferable for the diagnostic devices. However, the wax printed paper-based devices still require some development as well as improvement in analysis techniques and sensing mechanisms to compete with the current analytical techniques. Certain studies on sensing mechanisms130,142,146 show that paper platforms match the performance of the current analytical techniques in health sectors. The ASSURED criteria, which are the main advantages behind the future role of paper-based microfluidic devices, are tried to be achieved with paper-based platforms. However, the devices may move away from being affordable and user friendly if the detection mechanism is different than the colorimetric one as they may then need more complex equipment (e.g., voltage-tunable power device129). The readout devices such as cell-phones are small and portable in colorimetric assays, but still they may be costly for being carried in resource-limited environments and may require a power source.

As a fabrication process, the wax printing method is a two-step process i.e., the printing and the heating steps. Therefore, in resource-limited environments and remote settings in developing countries, it may be hard and time consuming to carry out these steps. However, the current studies show that in the following years, these struggles can be overcome. For example, a combined wax printing technique is recently developed by using a mini-type CO2 laser machine (size of a pen) along with a wax printer. That new technique proposes simultaneous heating, melting, and penetrating of the wax.150

The paper-based devices have also certain physical limitations for the detection. In the case of long-range penetration of sample solution while the sample of analyte flows through the paper, the concentration of the analyte may vary locally due to non-homogenous penetration of sample solution and the high proportion of the sample solution may fill the nonfunctional parts rather than the detection zone. In addition, the evaporation of the solution may affect the analyte concentration for the devices with chambers. Despite the fact that the evaporation problem can be solved by covering the wetted part of the paper by the help of a plastic tape or film as in the 3D microfluidic devices for performing the assays, the analyte may need to be in contact with open air.38 For instance, in cell proliferation assays, the cells as the target analytes require oxygen from the open air.33 Besides the evaporation problem and the non-homogenous distribution in a single detection part, in 3D devices the sample volume may also vary between each spot due to the channel configuration of multiple interlayers which enable sample dispersion. In order to solve this problem, channels can be designed considering the equal hydrodynamic resistance and layers can be stacked.151

The wax which prevents the solution from flowing in every direction and keeps it inside the wax-printed zones (i.e., chambers whose boundaries are made of wax) may constitute certain problems. For instance, certain biological solutions may have relatively low surface tension, which can result in the flowing of the solution through the hydrophobic barriers since the wax decreases the surface energy of the paper instead of filling the pores between the cellulose fibers.23

The limitations mentioned above constitute the challenges of the current paper based microfluidics research area. At present, the sensitivity problem seems to be overcome, as it has been handled by serious modification and treatments at the expense of increasing either the complexity of the assay preparation or the fabrication process. However, in one of the recent studies,152 unmodified paper was used as the platform for colorimetric assay in order to compare it with the paper modified by chitosan and sodium alginate (NaAlg). The results showed that the residual carboxyl groups on paper were sufficient to make bonds with the biomolecules, and there was no significant difference between the intensity values in both colorimetric assays.

V. RECENT ADVANCES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS