Abstract

Treatment of acute pancreatitis remains a challenge, with therapy focused on supportive care and treating the inciting etiology. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) inhibitors have shown promising results treating acute pancreatitis in animal models, but they have not been evaluated in human trials yet. A 25-year-old woman presented with ulcerative colitis. She was unresponsive to immunomodulators and developed acute pancreatitis shortly after initiation of a TNFα inhibitor. Her symptoms subsided after discontinuation of the medication, but reemerged when a different TNFα inhibitor was introduced to control her ulcerative colitis. Other potential etiologies were investigated and clinically excluded by laboratory and imaging studies.

Introduction

Drug-induced acute pancreatitis occurs at an incidence rate of 0.1–1.4%.1 Its diagnosis is challenging and is usually established after the exclusion of pancreatitis associated with gallstones, alcohol use, tobacco use, or hypertriglyceridemia. Parallel to the these common acute pancreatitis etiologies, patients frequently report the concomitant use of medications that have been documented to cause drug-induced acute pancreatitis. The level of evidence for medications causing drug-induced pancreatitis vary. Recurrent pancreatitis with re-challenge of the drug and the exclusion of other causes of pancreatitis provide the strongest evidence for drug-induced pancreatitis, which has not been reported for TNFα inhibitors.2

Case Report

A 25-year-old woman was diagnosed with proctitis in the context of ulcerative colitis through colonoscopy and biopsies. Despite maximum doses of oral and rectal mesalamine and intermittent corticosteroid doses over the course of 2 years, she developed pancolitis, and the decision was made to start infliximab (Remicade). However, after the second dose of infliximab, she developed new, acute epigastric pain that radiated to her back.

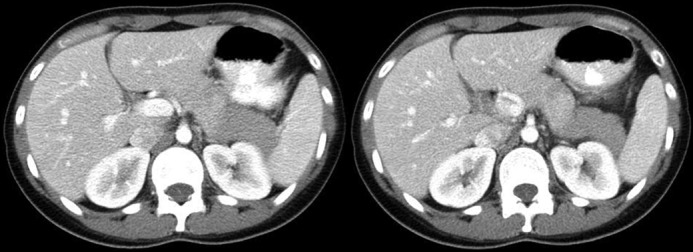

The patient was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis based on a lipase level of 5,000 U/L and computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast of the abdomen showing edematous pancreatitis with normal biliary anatomy and no evidence of choledocolithiasis (Figure 1). Further investigation showed normal liver function tests, triglycerides (66 mg/dL), and immunoglobulin G4 (21 mg/dL) levels, which excluded a biliary source of hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis. Corrected calcium was 9.3 mg/dL, measured calcium was 8.2 mg/dL, and albumin was 2.8 mg/dL. The patient denied any alcohol or tobacco consumption and had no family history of pancreatitis. Infliximab was discontinued due to concern for drug-induced pancreatitis.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography showing edematous pancreatitis, predominantly at the tail of the pancreas.

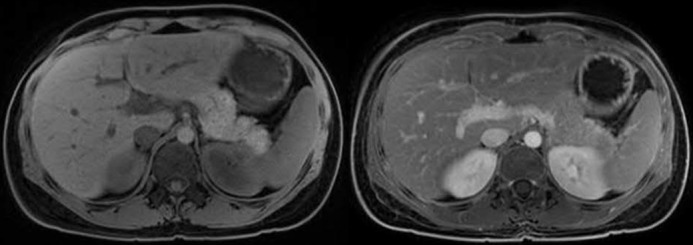

After 3 days of hospitalization and supportive therapy, the patient improved and was discharged home with the plan to add 6-mercaptopurine to her previous treatment regimen of mesalamine and corticosteroids. After 4 months of this regimen, with 6-mercaptopurine metabolites at maximum therapeutic range, her symptoms progressively worsened. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) sequences of her abdomen performed approximately 5 months after the episode of pancreatitis showed persistent colitis but complete resolution of pancreatitis and no evidence of chronic or autoimmune pancreatic disease (Figure 2). Interim blood chemistry tests showed lipase at 92 U/L, amylase at 70 U/L, and normal liver function tests.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen showing normal pancreatic volume and signal density, normal pancreatic ducts, and the absence of gallstones, defining resolution of pancreatitis.

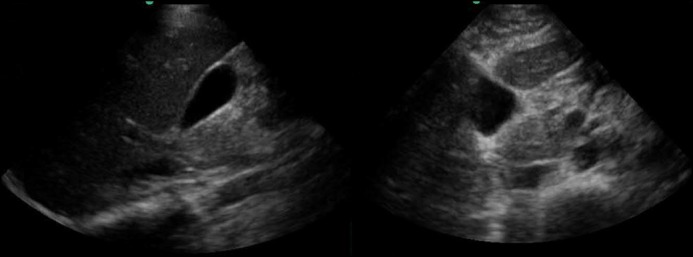

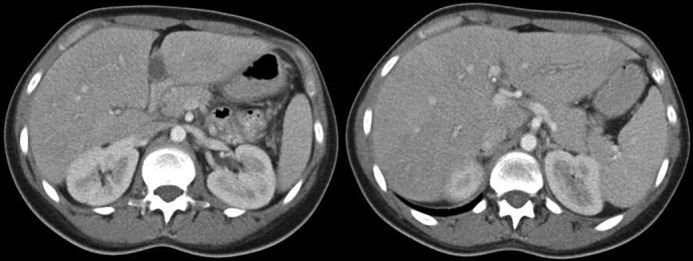

Discontinuation of 6-mercaptopurine and initiation of 40 mg of adalimumab was determined to be the best next step in her management. After the second dose of adalimumab, the patient presented to the emergency department with epigastric pain that radiated to her back, exacerbated by oral intake. Testing revealed elevated lipase (1,500 U/L), which was diagnostic for acute pancreatitis in conjunction with classic abdominal pain. No cross-sectional imaging was performed at that point. Her liver function tests remained normal (total bilirubin 0.3 mg/dL), which made choledocolithiasis unlikely in conjunction with a normal abdominal ultrasound (Figure 3). Again, the patient denied tobacco and alcohol use, and the pain resolved after 2 days of supportive care. Repeat contrast-enhanced CT performed approximately 2 weeks after symptom onset showed no signs of the pancreatitis and no cystic collection (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Gallbladder ultrasound without signs of cholelithiasis or biliary sludge, with normal appearance and size of common bile duct (2 mm).

Figure 4.

Computed tomography confirming resolution of acute pancreatitis.

Since the discontinuation of TNF-alpha (TNFα) inhibitors, the patient has not experienced any more episodes of pancreatitis over a follow-up of 18 months. In light of poor response to previously used medications and due to the limited pharmacological options for the management of ulcerative colitis, she underwent a total colectomy with end ileostomy followed by restorative completion proctocolectomy with ileal J-pouch anal anastomosis and diverting loop ileostomy.

Discussion

The patient’s acute pancreatitis was likely associated with exposure to TNFα inhibitors. Biliary, alcohol, triglyceride, and hypercalcemia-induced acute pancreatitis etiologies were investigated and excluded in both hospitalizations. Several aspects of this case presentation argued strongly against autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP). First IgG4 level was normal. Second, each episode of acute pancreatitis resolved spontaneously within days without the use of steroids. Third, contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging did not show any features of autoimmune pancreatitis, although only CT was performed during the first acute pancreatitis episode, whereas contrast-enhanced MRI with MRCP sequence was performed after the resolution of pain, presumably related to acute pancreatitis. These features were not consistent with type 1 or type 2 AIP based on HISORt criteria.

This case suggests that the TNFα inhibitors class may have caused acute pancreatitis given the following details: (1) occurrence of pancreatitis was preceded by the initiation of this drug class; (2) thorough clinical investigation for other causes failed to explain a different etiology; (3) reintroduction of the drug class preceded reoccurrence of pancreatitis; (4) resolution of disease following the interruption of TNFα inhibitors administration; and (5) absence of new pancreatitis episodes after discontinuation of this drug class.

Multiple mechanisms are hypothesized to cause drug-induced pancreatitis, including pancreatic duct constriction, arteriolar thrombosis, direct and indirect toxic effects, and hypersensitivity reactions.3-5 In terms of adverse TNFα inhibitor reactions, abnormalities in liver function tests have been observed, including acute hepatitis, isolated cholestasis, and transient elevation of transaminases, which can be misinterpreted as biliary obstruction, although this was not present in this case.6 In this context, an immune-mediated mechanism of hepatitis is hypothesized.7,8 Infliximab is also known to cause lipid profile abnormalities, which theoretically could lead to hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis, although this mechanism was excluded in our case.9,10

Acute pancreatitis is accompanied by a significant rise in proinflammatory cytokines including TNFα, which is thought to contribute to a paracrine immune activation.11 Animal models demonstrated a correlation between TNFα level and the severity of acute pancreatitis. Whether TNFα inhibitors are beneficial to treat acute pancreatitis in humans is unclear. However, animal studies reported improved outcomes of acute pancreatitis with TNFα inhibitors.12-15 Future human studies addressing medical treatment of acute pancreatitis should investigate whether TNFα inhibitors should be considered as a possible cause of acute pancreatitis.

Disclosures

Author contributions: ME Werlang interpreted the data, wrote and revised the manuscript, and is the article guarantor. MD Lewis interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. MJ Bartel wrote and revised the manuscript.

Financial disclosure: None to report.

Informed consent was obtained for this case report.

Previous presentation: This case was presented at the American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting; October 17–22, 2014; Philadelphia, PA.

References

- 1.Hung WY, Abreu Lancfranco O. Contemporary review of drug-induced pancreatitis: A different perspective. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014; 5:405–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badalov N, Baradarian R, Iswara K, et al. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis: An evidence-based review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 5(6):648–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones MR, Hall OM, Kaye AM, et al. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis: A review. Ochsner J. 2015; 15:45–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Underwood TW, Frye CB. Drug-induced pancreatitis. Clin Pharm. 1993; 12:440–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaurich T. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008; 21:77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossi RE, Parisi I, Despott EJ, et al. Anti-tumour necrosis factor agent and liver injury: Literature review, recommendations for management. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:17352–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thiéfin G, Morelet A, Heurgué A, et al. Infliximab-induced hepatitis: Absence of cross-toxicity with etanercept. Joint Bone Spine. 2008; 75:737–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kluger N, Girard C, Guillot B, et al. Efficiency and safety of etanercept after acute hepatitis induced by infliximab for psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009; 89:332–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koutroubakis IE, Oustamanolakis P, Malliaraki N, et al. Effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition with infliximab on lipid levels and insulin resistance in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009; 21:283–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antoniou C, Dessinioti C, Katsambas A, et al. Elevated triglyceride and cholesterol levels after intravenous antitumour necrosis factor-alpha therapy in a patient with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2007; 156:1090–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartel M, Hänsch GM, Giese T, et al. Abnormal crosstalk between pancreatic acini and macrophages during the clearance of apoptotic cells in chronic pancreatitis. J Pathol. 2008; 215:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li WD, Jia L, Ou Y, et al. Infliximab: Protective effect to intestinal barrier function of rat with acute necrosis pancreatitis at early stage. Pancreas. 2013; 42:366–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang YX, Li WD, Jia L, et al. Infliximab enhances the therapeutic effectiveness of octreotide on acute necrotizing pancreatitis in rat model. Pancreas. 2012; 41:849–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norman JG, Fink GW, Messina J, et al. Timing of tumor necrosis factor antagonism is critical in determining outcome in murine lethal acute pancreatitis. Surgery. 1996; 120:515–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes CB, Gaber LW, Mohey el-Din AB, et al. Inhibition of TNF alpha improves survival in an experimental model of acute psancreatitis. Am Surg. 1996; 62:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]