Abstract

Previous transcriptome studies of the human endometrium have revealed hundreds of simultaneously up- and down-regulated genes that are involved in endometrial receptivity. However, the overlap between the studies is relatively small, and we are still searching for potential diagnostic biomarkers. Here we perform a meta-analysis of endometrial-receptivity associated genes on 164 endometrial samples (76 from ‘pre-receptive’ and 88 from mid-secretory, ‘receptive’ phase endometria) using a robust rank aggregation (RRA) method, followed by enrichment analysis, and regulatory microRNA prediction. We identify a meta-signature of endometrial receptivity involving 57 mRNA genes as putative receptivity markers, where 39 of these we confirm experimentally using RNA-sequencing method in two separate datasets. The meta-signature genes highlight the importance of immune responses, the complement cascade pathway and the involvement of exosomes in mid-secretory endometrial functions. Bioinformatic prediction identifies 348 microRNAs that could regulate 30 endometrial-receptivity associated genes, and we confirm experimentally the decreased expression of 19 microRNAs with 11 corresponding up-regulated meta-signature genes in our validation experiments. The 57 identified meta-signature genes and involved pathways, together with their regulatory microRNAs could serve as promising and sought-after biomarkers of endometrial receptivity, fertility and infertility.

Introduction

The period of endometrial receptivity, also known as the window of implantation (WOI), is the limited time (one to two days) when luminal epithelium is favourable for embryo adhesion as the first step of implantation1. Successful embryo implantation depends on synchronization of a viable embryo and receptive endometrium. In fact, inadequate uterine receptivity has been estimated to contribute to one third of implantation failures, whereas the embryo itself is responsible for two thirds of them2, 3. In assisted reproductive technologies where good-quality embryos are transferred as a standard of care, implantation failure remains an unsolved obstacle4–6. In patients with recurrent implantation failure (RIF) temporal displacement of the WOI has been described in one out of four patients7, thus suggesting the possibility of these women suffering RIF of endometrial origin. Further, impaired decidualization of endometrial stromal cells that predisposes to late implantation may negate endometrial ‘embryo quality control’ and cause early pregnancy failure8–10. Hence, better understanding of endometrial receptivity and the importance of the mechanisms involved in mid-secretory endometrial functions is warranted.

From the first histological dating methods11, 12 to the new ‘omics’ technologies, extensive efforts have been made to understand and characterise receptive endometrium. Traditional endometrial dating criteria, like tissue histology, are obsolete, since their accuracy, reproducibility and functional relevance have been questioned in various randomised studies13, 14. This has encouraged further investigation and application of new technologies to diagnose endometrial receptivity objectively, since reliable diagnostic markers are still lacking and the molecular mechanisms remain largely unclear15–17.

With the ‘omics’ revolution, the quest for the transcriptomic signature of human endometrial receptivity has revealed hundreds of simultaneously up- and down-regulated genes implicated in the phenomenon (reviewed in ref. 18). While any given study yields a number of genes, the overlap between different studies is relatively small. The perceived limitations of this technology have been well defined and lie in differences in experimental design, timing and conditions of endometrial sampling, selection criteria regarding patients, transcriptome array/sequencing platforms and genome annotation versions used, pipelines for data processing and a lack of consistent standards for data presentation19–23.

To overcome the aforementioned limitations in endometrial transcriptome analyses, we applied a recently published robust rank aggregation (RRA) method24, followed by enrichment analysis, to identify a meta-signature or consensus signature of highly putative biomarkers of endometrial receptivity. Additionally, we set up to analyse possible microRNAs that could influence the endometrial receptivity-associated genes/mRNAs. Further, we aimed to experimentally validate the meta-signature mRNA genes and their regulatory miRNAs in two independent sample sets.

Results

Identification of relevant studies

The search process and results of the systematic literature review are presented in detail in Supplementary Figure 1. Eventually, out of 57 eligible publications, 14 remained suitable for qualitative analysis. Five eligible studies25–29 were not included in the final analysis, since the data on lists of differentially expressed genes were not available publicly nor in response to requests to the authors. A detailed description of the studies included in the final analysis is presented in Table 1. Our pooled dataset obtained from the nine remaining studies covered 76 ‘pre-receptive’-phase (28 biopsy samples from the proliferative phase and 48 from the early secretory phase) and 88 mid-secretory, ‘receptive’ phase endometrial samples.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the analysed datasets. ES indicates early secretory phase, MS – mid-secretory phase, cd – cycle day, LH – luteinizing hormone, FC – fold change, N/S – not specified, * – samples pooled for microarray analysis, ** – ERA test training that was performed on 68 additional endometrial samples.

| First author and reference | Participants | Region | Biopsy obtained | Cycle dating | First sample (day, n) | Second sample (day, n) | Array/sequencing platform | FC (cut-off) | Up-regulated transcripts (n) | Down-regulated transcripts (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-secretory vs. proliferative | ||||||||||

| Kao85 | Normally cycling women | North America | Pipelle catheter | urinary LH | cd 8–10, n = 4 | LH+8-10, n = 7 | Affymetrix Hu95A | ≥2.0 | 156 | 377 |

| Borthwick86 | Regular cycles, normal pelvis | Europe | N/S | urinary LH | cd 9-11, n = 5 | LH+6-8, n = 5 | Affymetrix Hu95A-E* | ≥2.0 | 90 | 46 |

| Altmäe37 | Healthy fertile volunteers | Europe | Pipelle catheter | urinary LH | cd 7, n = 4 | LH+7, n = 4 | Affymetrix HG-U133 plus 2.0 | p < 0.05 | 920 | 1257 |

| Mid-secretory vs. early secretory | ||||||||||

| Carson87 | Fertile volunteers | North America | Pipelle catheter | urinary LH | LH+2-4, n = 3 | LH+7-9, n = 3 | Affymetrix Hu95A* | ≥2.0 | 323 | 370 |

| Riesewijk88 | Normally cycling women | Europe | Pipelle catheter | urinary LH | LH+2, n = 5 | LH+7, n = 5 | Affymetrix Hu95A | ≥3.0 | 153 | 58 |

| Mirkin89 | Healthy fertile oocyte donors | North America | Pipelle catheter | urinary LH | LH+3, n = 3 | LH+8, n = 5 | Affymetrix HG-U95Av2 | ≥2.0 | 49 | 58 |

| Talbi33 | Normally cycling women | North America | Pipelle catheter | Noyes | ES, n = 3 | MS, n = 8 | Affymetrix HG-U133 plus 2.0 | ≥1.5 | 1415 | 1463 |

| Diaz-Gimeno30 | Healthy fertile oocyte donors | Europe | Pipelle catheter | urinary LH | LH+1, n = 5; LH+3, n = 5; LH+LH+5, n = 5;**cd 8-12, n = 15; **LH+1–+5, n = 13; **LH+7, n = 40 | LH+7, n = 5 | Agilent Whole Human Genome Oligo Microarray | ≥3.0 | 143 | 95 |

| Hu38 | Normally cycling women | Asia | Pipelle catheter | urinary LH | LH+2, n = 6 | LH+7, n = 6 | RNA-seq Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx | p < 0.001, FC > 2 | 1099 | 1273 |

Meta-signature of endometrial receptivity-associated genes

Using robust rank aggregation analysis, we identified a statistically significant meta-signature of 52 up-regulated and five down-regulated genes in mid-secretory vs. ‘pre-receptive’ endometrium (see Table 2). The up-regulated transcripts with the highest scores in receptive-phase endometrium were PAEP, SPP1, GPX3, MAOA and GADD45A. The five down-regulated transcripts identified as receptivity-associated genes were SFRP4, EDN3, OLFM1, CRABP2 and MMP7.

Table 2.

List of genes identified as specific biomarkers of mid-secretory endometrium when assessed in comparative transcriptome analyses with proliferative and early secretory endometrium in nine datasets. 52 genes are up-regulated in mid-secretory endometrium, while five are down-regulated (↓).

| ENTREZ ID | HUGO Symbol | HUGO Name | VAL* | VAL** | RRA score | Adjusted P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5047 | PAEP b,c,d,e | Progestagen-associated endometrial protein | 90 | 7.68E-18 | 2.99E-13 | |

| 6696 | SPP1 b,d,e | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (osteopontin) | 30, 32, 87, 89, 91 | 92 | 2.06E-15 | 8.04E-11 |

| 2878 | GPX3 b,c,d,e | Glutathione peroxidase 3 | 30, 86, 88, 91 | 1.89E-14 | 7.40E-10 | |

| 4128 | MAOA a,b,d,e | Monoamine oxidase A | 17 | 93 + | 2.32E-13 | 9.04E-09 |

| 1647 | GADD45A b,c,d,e | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, alpha | 2.73E-13 | 1.06E-08 | ||

| 22943 | DKK1 a,b,d,e | Dickkopf WNT signalling pathway inhibitor 1 | 17, 33, 85 | 94 | 2.80E-13 | 1.09E-08 |

| 1364 | CLDN4 a,b,d,e | Claudin 4 | 87, 88 | 87, 95 | 9.14E-13 | 3.57E-08 |

| 722 | C4BPA b,d,e | Complement component 4 binding protein, alpha | 91 | 56 | 1.60E-12 | 6.23E-08 |

| 3600 | IL15 a,b,d,e | Interleukin 15 | 96 | 3.36E-12 | 1.31E-07 | |

| 1604 | CD55 a,b,d,e | CD55 molecule, decay accelerating factor for complement | 33 | 97 | 5.47E-12 | 2.14E-07 |

| 3400 | ID4 b | Inhibitor of DNA binding 4, dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein | 6.43E-12 | 2.51E-07 | ||

| 10578 | GNLY b,d | Granulysin | 98+ | 1.78E-11 | 6.96E-07 | |

| 1356 | CP a,b,d | Ceruloplasmin | 2.81E-11 | 1.10E-06 | ||

| 6505 | SLC1A1 a,d,e | Solute carrier family 1, member 1 | 88 | 5.27E-11 | 2.06E-06 | |

| 1803 | DPP4 b,c,d,e | Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 | 32 | 99, 100 | 7.44E-11 | 2.90E-06 |

| 6947 | TCN1 d,e | Transcobalamin I | 1.54E-10 | 6.03E-06 | ||

| 1675 | CFD a,b,d | Complement factor D | 2.56E-10 | 9.99E-06 | ||

| 307 | ANXA4 a,b,d,e | Annexin A4 | 17, 89, 91 | 101 | 1.50E-09 | 5.85E-05 |

| 1942 | EFNA1 d | Ephrin-A1 | 102 | 1.55E-09 | 6.06E-05 | |

| 2634 | GBP2 a,b,d | Guanylate binding protein 2, interferon-inducible | 1.63E-09 | 6.38E-05 | ||

| 347 | APOD b,d,e | Apolipoprotein D | 85, 91 | 103 | 3.05E-09 | 1.19E-04 |

| 604 | BCL6 a,d | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 6 | 104 | 4.42E-09 | 1.72E-04 | |

| 1052 | CEBPD d | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein, delta | 105 | 5.09E-09 | 1.99E-04 | |

| 36 | ACADSB e | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short/branched chain | 6.16E-09 | 2.40E-04 | ||

| 11067 | C10orf10 a,d | Chromosome 10 open reading frame 10 | 7.24E-09 | 2.83E-04 | ||

| 8714 | ABCC3 a,d,e | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C, member 3 | 7.53E-09 | 2.94E-04 | ||

| 4495 | MT1G b,d,e | Metallothionein 1G | 30, 38, 86 | 8.16E-09 | 3.19E-04 | |

| 384 | ARG2 a,d | Arginase 2 | 106 | 8.52E-09 | 3.33E-04 | |

| 1311 | COMP b,d,e | Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein | 32 | 9.02E-09 | 3.52E-04 | |

| 50486 | G0S2 b,e | G0/G1 switch 2 | 1.10E-08 | 4.31E-04 | ||

| 7103 | TSPAN8 a,d,e | Tetraspanin 8 | 1.22E-08 | 4.76E-04 | ||

| 1672 | DEFB1 a,d | Defensin, beta 1 | 107 | 1.43E-08 | 5.57E-04 | |

| 4217 | MAP3K5 b,d,e | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 5 | 1.54E-08 | 6.00E-04 | ||

| 1910 | EDNRB c,d,e | Endothelin receptor type B | 108+ | 2.34E-08 | 9.15E-04 | |

| 158471 | PRUNE2 b | Prune homolog 2 | 3.48E-08 | 1.36E-03 | ||

| 6286 | S100P a,b,d,e | S100 calcium binding protein P | 17, 28 | 25, 28 | 4.01E-08 | 1.56E-03 |

| 3484 | IGFBP1 e | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 | 33, 85 | 109 | 4.92E-08 | 1.92E-03 |

| 11056 | DDX52 | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 52 | 5.97E-08 | 2.33E-03 | ||

| 710 | SERPING1 a,b,d | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade G, member 1 | 7.05E-08 | 2.75E-03 | ||

| 84159 | ARID5B d,e | AT rich interactive domain 5B | 8.69E-08 | 3.40E-03 | ||

| 3914 | LAMB3 b,d,e | Laminin, beta 3 | 26 | 1.45E-07 | 5.66E-03 | |

| 316 | AOX1 a,d,e | Aldehyde oxidase 1 | 91 | 2.09E-07 | 8.17E-03 | |

| 3620 | IDO1 | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 | 110 | 2.67E-07 | 1.04E-02 | |

| 302 | ANXA2 b,e | Annexin A2 | 111 | 3.26E-07 | 1.27E-02 | |

| 3026 | HABP2 c,d,e | Hyaluronan binding protein 2 | 112 | 3.26E-07 | 1.27E-02 | |

| 715 | C1R b,e | Complement component 1, r subcomponent | 3.26E-07 | 1.27E-02 | ||

| 360 | AQP3 e | Aquaporin 3 | 113 | 4.27E-07 | 1.66E-02 | |

| 6990 | DYNLT3 a | Dynein, light chain, Tctex-type 3 | 5.07E-07 | 1.98E-02 | ||

| 4496 | MT1H d,e | Metallothionein 1 H | 114 | 8.16E-07 | 3.18E-02 | |

| 4837 | NNMT d | Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase | 91 | 8.74E-07 | 3.41E-02 | |

| 10397 | NDRG1 d | N-myc downstream regulated 1 | 115 | 1.01E-06 | 3.95E-02 | |

| 2028 | ENPEP | Glutamyl aminopeptidase | 1.11E-06 | 4.32E-02 | ||

| 6424 | SFRP4↓b | Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 | 17 | 5.95E-11 | 2.32E-06 | |

| 1908 | EDN3↓b | Endothelin 3 | 108+ | 3.06E-10 | 1.20E-05 | |

| 10439 | OLFM1↓a,b | Olfactomedin 1 | 116 | 1.65E-09 | 6.46E-05 | |

| 1382 | CRABP2↓a,b | Cellular retinoic acid binding protein 2 | 56 | 1.97E-08 | 7.68E-04 | |

| 4316 | MMP7↓a,b | Matrix metallopeptidase 7 | 4.07E-07 | 1.59E-02 |

Genes validated in our independent sample sets of endometrial samples at LH+2 vs. LH+8 from healthy fertile women analysed with RNA-seq and cell type-specific RNA-seq methods are highlighted in bold. Genes present in the ERA diagnostic tool are underlined. Genes also identified in previous data-mining/review studies are indicated in super-scripts: a17, b31, c19, d29, and e32.

VAL* indicates mRNA validation experiments in previous transcriptomic studies on mid-secretory endometrium using real-time PCR, Northern blot or in situ hybridisation analyses.

VAL** indicates protein validation analyses in mid-secretory endometrium. + stands for validation in other species (mouse, bovine or rhesus monkey).

Enrichment analyses

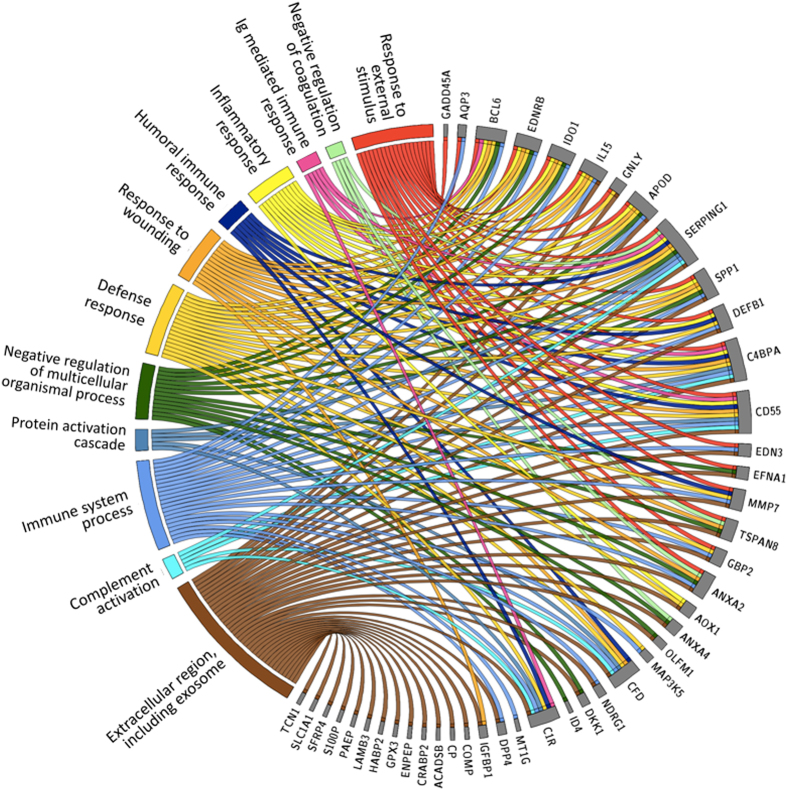

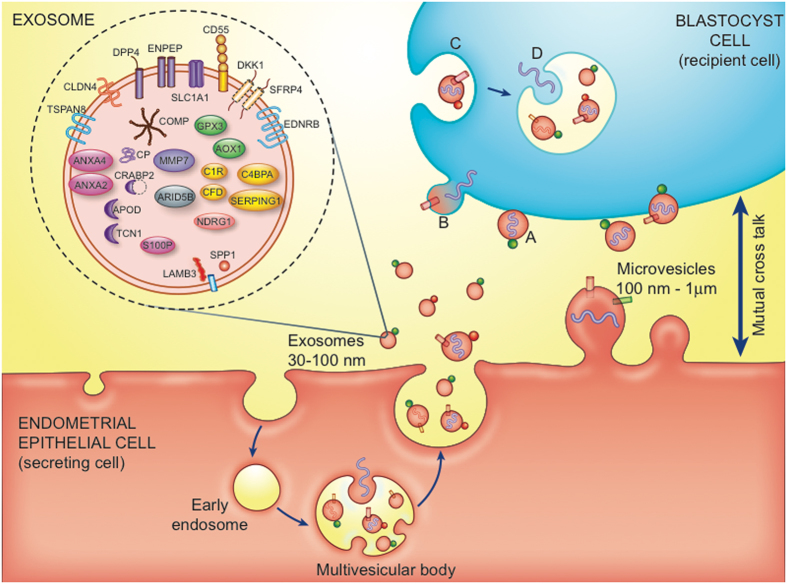

We used up-to-date enrichment analysis software (g:Profiler) for analysis of biological processes and pathways connected to the meta-signature of mid-secretory endometrium. A significant proportion of the genes were involved in biological processes such as responses to external stimuli, responses to wounding, inflammatory responses, negative regulation of coagulation, humoral immune responses, and immunoglobulin-mediated immune responses, among others. Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1 show the connections of the 57 endometrial receptivity genes with their respective Gene Ontology biological processes. The only significantly enriched pathway related to the meta-signature genes was a KEGG pathway of complement and coagulation cascades, where the identified genes were connected to the complement cascade part (p = 0.00112) (see Fig. 2). A significant number of the genes were also connected with the extracellular region and exosomes. In order to confirm the involvement of exosomes, we searched for the presence of the meta-signature genes in human exosomes based on the exosome database, ExoCarta (exocarta.org). Fisher’s Exact Test was performed to analyse if meta-signature genes were over represented in the exosome database. All the human protein coding genes were downloading from ENSEMBL v75 database (version February 2014) and mRNAs or proteins from Exocarta database (exocarta.org). Altogether, meta-signature genes had 2.13 times higher probability to be in the exosomes than the rest of the protein-coding genes in the human genome (Fisher’s exact test, two-sided p = 0.0059). The 28 identified proteins from the meta-signature gene list that have been shown to be in exosomes are presented in Fig. 3 that illustrates the involvement of extracellular vesicles (exosomes and microvesicles) in embryo implantation process.

Figure 1.

Gene ontology (GO) processes and the pathways most strongly enriched among endometrial receptivity-associated genes. Genes are presented on the right side on the circle and the correlating GO processes, cellular compartments and pathways are on the left side.

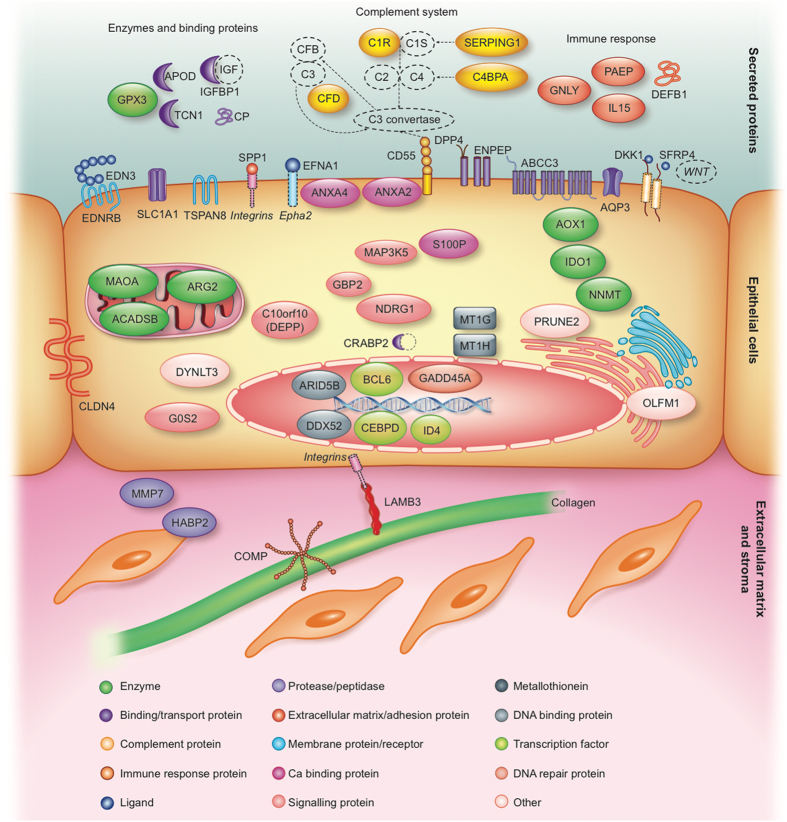

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of the 57 meta-signature genes, their literature-based localisation and involvement in the mid-secretory phase endometrium. Different membrane-associated proteins (ABCC3, ANXA2, ANXA4, AQP3, CD55, DKK1, DPP4, EDN3, EDNRB, EFNA1, ENPEP, SFRP4, SLC1A1, SPP1, TSPAN8), epithelial cell tight junction protein (CLDN4), secreted enzymes and binding proteins (APOD, CP, GPX3, IGFBP1, TCN1), secreted immune response proteins (DEFB1, GLNY, IL15, PAEP), extracellular matrix-associated proteins (COMP, HABP2, LAMB3, MMP7), different enzymes (ACADSB, AOX1, ARG2, IDO1, MAOA, NNMT), signalling proteins (C10orf10, GBP2, G0S2, MAP3K5, NDRG1), metallothioneins (MT1G, MT1H), DNA binding and repair proteins (ARID5B, DDX52, GADD45A), transcription factors (BCL6, CEBPD, ID4), and other intracellular proteins (CRABP2, DYNLT3, OLFM1, PRUNE2, S100P) are indicated. Additionally, the enriched KEGG pathway of complement cascade with the identified genes C1R, SERPING1, CD55, C4BPA and CFD is highlighted. (Figure created by Elsevier Illustration Service).

Figure 3.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) – exosomes and microvesicles, in embryo-endometrium cross-talk. In the exosomes the meta-signature genes are highlighted (based on ExoCarta database). Exosomes (30–100 nm) are generated from inward budding of the endosomal membrane, resulting in formation of a multivesicular body. Microvesicles (100 nm–1 μm) are produced by direct budding of the plasma membrane. Membrane-associated (bubbles) and transmembrane proteins (cylinders), and nucleic acids (DNA, RNA, curved symbols) are selectively incorporated into the EVs. EVs may dock on the plasma membrane of a target cell (A), fuse directly with the plasma membrane (B), or be endocytosed (C). Endocytosed vesicles may subsequently fuse with the delimiting membrane of an endocytic compartment (D). Both (B and D) pathways result in the delivery of proteins and nucleic acids into the membrane or cytosol of the target cell. (Figure adapted with permission from62, 84, created by Elsevier Illustration Service).

Validation of meta-signature genes in two independent sample sets

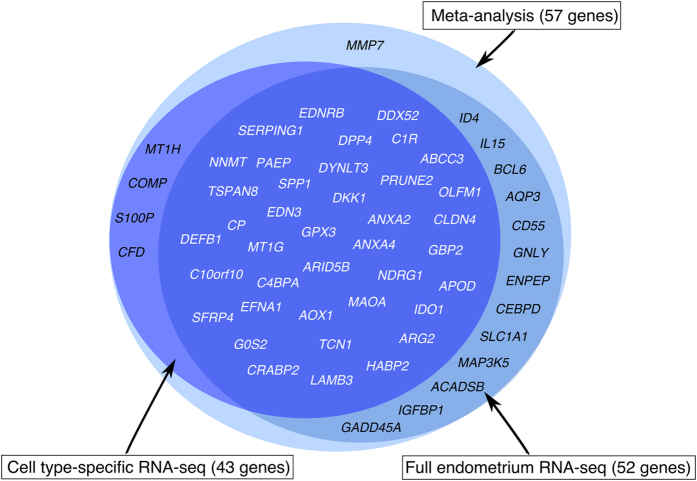

Meta-analysis identified 57 genes differentially expressed between the ‘pre-receptive’ and mid-secretory endometrium, where 52 genes were up- and five were down-regulated at WOI. Our RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis on 20 independent endometrial biopsy samples from fertile women confirmed the differential expression of 52 meta-signature genes (all of them with fold change of ≥3) – 48 of these genes were likewise up-regulated and four were down-regulated (CRABP2, EDN3, OLFM1, SFRP4) in the mid-secretory endometria (Fig. 4). MMP7 and CFD were not differentially expressed in our RNA-seq analysis of LH+8 vs. LH+2 phase endometria. Three genes, COMP, MT1H, S100P, did not pass the initial filtering of RNA-seq data (counts per million, CPM > 2 in at least 15 samples), which might be due to their low expression levels. The filtering was applied to rule out transcripts with very low or inconsistent expression levels across individuals.

Figure 4.

Validation of the meta-signature genes in two independent sample sets. RNA-seq analysis of endometrial tissue samples confirmed differential expression of 52 (91.2%) meta-signature genes in the mid-secretory phase endometrium vs. early secretory phase endometrium. Cell type-specific RNA-seq analysis of endometrial epithelial and stromal cells confirmed differential expression of 43 (75.4%) meta-signature genes in those cell populations in the mid-secretory endometrium vs. early secretory endometrium. In total, 39 (68.4%) meta-signature genes (typed in white colour) were identified in validation experiments on two different sample sets, where 35 genes were up-regulated and 4 genes (CRABP2, EDN3, OLFM1, SFRP4) down-regulated in the mid-secretory phase endometrium.

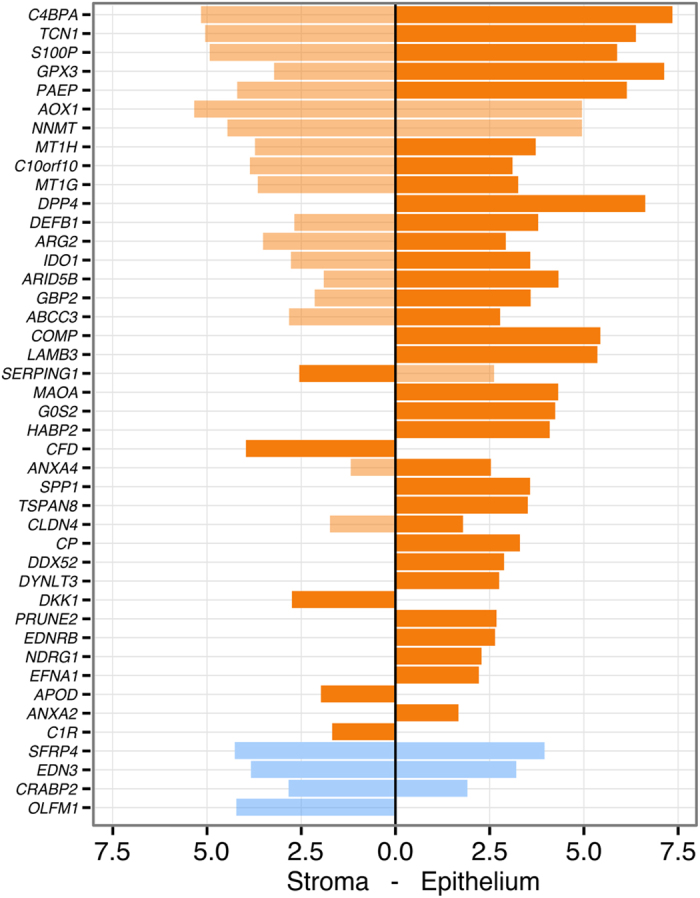

Next, we investigated the expression of the 57 meta-signature genes in FACS (fluorescence-activated cell sorting)-sorted endometrial epithelial and stromal cells from two time points in the menstrual cycle, early secretory vs. mid-secretory phase, from 16 fertile women. Thirty-nine of those genes were significantly up-regulated and four were down-regulated (CRABP2, EDN3, OLFM1, SFRP4) in the receptive phase in those cell populations (all of them with fold change of ≥2) (Fig. 4; Supplementary Figure 2). Although most of the genes were up-regulated in both cell types, it is notable that the expression of ANXA2, COMP, CP, DDX52, DPP4, DYNLT3, EDNRB, EFNA1, G0S2, HABP2, LAMB3, MAOA, NDRG1, PRUNE2, SPP1, and TSPAN8 was epithelium-specific (Fig. 5), while none of the genes was down-regulated in the epithelial cells only. The stroma-specific up-regulated genes were APOD, CFD, C1R and DKK1, and down-regulated gene was OLFM1 (Fig. 5). It is noteworthy that although most of the genes were up-regulated in both cell types, the expression of these genes was still higher in the epithelial cells.

Figure 5.

Validation of the meta-signature genes on cell type-specific RNA-seq data. Significantly up-regulated (orange) and down-regulated (blue) genes in FACS-sorted stromal and epithelial cells. The x-scale represents log2(FC) between LH+8 vs. LH+2 comparisons in stromal and epithelial cells. When comparing the gene expression values between epithelial vs. stromal cells in the mid-secretory phase endometrium (LH+8), most genes were more up-regulated in the epithelial cells (higher expression highlighted as darker orange). All reported results are significant at FDR < 0.05.

Further validation of these confirmed meta-signature genes was carried out with real-time PCR. Up-regulation of DDX52, DYNLT3, C1R and APOD expression levels in the receptive phase endometrial samples was confirmed (Supplementary Figure 3). Furthermore, the cell-specific up-regulated DDX52 and DYNLT3 expression was confirmed in FACS-sorted epithelial cells, and the stromal cell-specific C1R and APOD up-regulation was confirmed in the FACS-sorted stromal cells (Supplementary Figure 3).

In conclusion, the validation of the 57 meta-analysis consensus genes of the receptive phase endometrium among the two independent sets of endometrial tissue samples and cell-populations analysed confirmed the differential expression of 39 genes, with 35 up- and 4 down-regulated expression during WOI (Fig. 4).

In silico analysis of potential microRNAs regulating meta-signature genes

To evaluate the potential regulation of the 57 meta-signature genes, we predicted their putative regulatory-microRNAs using three different in silico target prediction algorithms. DIANA microT-CDS predicted 1,355 microRNAs with 12,627 potential binding sites, TargetScan 7.0 predicted 2,521 microRNAs with 32,560 potential binding sites, and miRanda predicted 2,568 microRNAs with 42,413 potential binding sites. The overlap between all three algorithms resulted in 818 microRNAs and 1,403 potential unique binding sites for 43 meta-signature genes (Supplementary Table 2).

To add an additional filter to the bioinformatic predictions, we overlaid those with experimentally determined Argonaute binding sites (microRNAs regulate gene expression by guiding Argonaute proteins to specific target mRNA sequences), mined from publicly available AGO-CLIP datasets. Out of 1,403 intersected potential binding sites, 395 showed overlap with experimentally determined Argonaute binding site in human cell lines, filtering down to the most probable microRNA and mRNA interactions. These 395 sites included interactions between 30 genes from our original meta-signature gene list and 348 microRNAs (Supplementary Table 3).

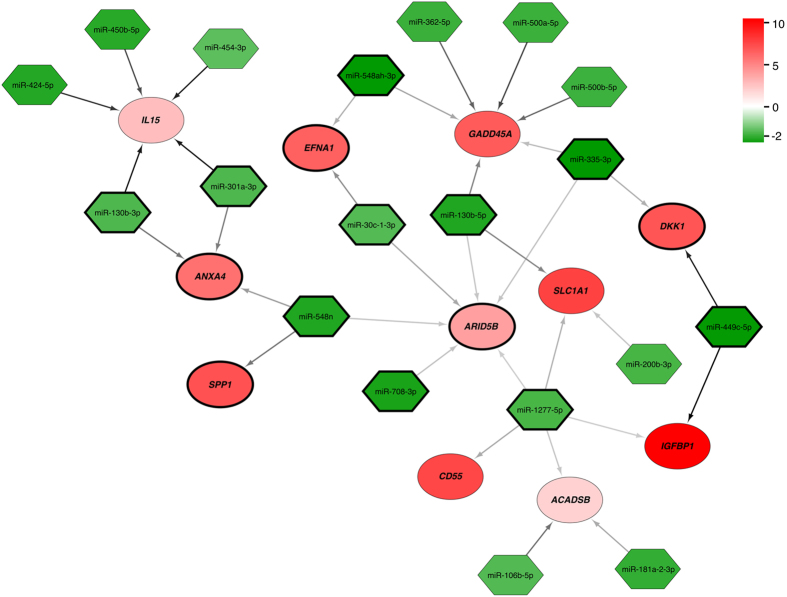

Validation analysis of predicted microRNAs and target mRNAs in independent sample set

In silico analysis of potential microRNAs regulating the meta-signature genes predicted interactions between 30 meta-signature genes and 348 microRNAs. Using the list of the predicted interactions, we investigated if these potentially interacting microRNAs are significantly regulated in our endometrial microRNA-sequencing data on endometrial biopsies from the mid-secretory phase vs. early secretory phase of healthy fertile women. We identified 19 microRNAs that were significantly down-regulated in the mid-secretory endometria with corresponding 11 meta-signature genes to be significantly up-regulated in our sample set (Fig. 6). Based on the TargetScan context++ scores, the probability of the interaction between microRNA and its target gene seems to be higher in pairs miR-449c-5p and DKK1, miR-450b-5p, miR-424-5p, miR-130b-3p and IL15, miR-500a-5p and GADD45A, and miR-181a-2-3p and ACADSB. When focussing only on the genes that were confirmed in both independent validation analyses (RNA-seq of endometrial biopsies and cell type-specific RNA-seq), five target genes (ANXA4, ARID5B, DKK1, EFNA1 and SPP1) and 10 microRNAs remained important (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

In silico predicted interactions between significantly up-regulated mRNAs (red) and down-regulated microRNAs (green) in LH+8 vs. LH+2 endometrium. The colour intensity indicates the strength of up- or down-regulation (FDR < 0.05). The colour of the arrows between the microRNA and mRNA represents TargetScan context++ score (see Supplementary Table 2 for scores), where darker arrow shows more probable interaction. The number of arrows between microRNA and mRNA indicates different microRNA binding sites within the same transcript. Meta-signature genes that were confirmed in both independent validation analyses together with their corresponding miRNAs are highlighted with black circle/diamond borders.

Discussion

In this report, we present a systematic review and meta-analysis approach together with comprehensive experimental validation in order to identify promising biomarkers and molecular pathways involved in mid-secretory endometrial functions. Analysing the lists of differentially expressed genes from previously published expression profiling studies, we established a meta-signature of receptive endometrium with 57 genes as putative receptivity biomarkers. Interestingly, the commercial transcriptome-based endometrial receptivity diagnostic tool ERA (Endometrial Receptivity Array)7, 30 shares 47 genes in common with the identified meta-signature. Validation of the meta-signature genes in two different sample sets of healthy fertile women in mid-secretory vs. early secretory endometria using the up-to-date transcriptome analysis by RNA-seq confirmed 39 meta-signature genes.

The human endometrial transcriptome has been extensively studied in the past decade in a search of identifying diagnostic markers of receptive endometrium and to provide more understanding into the complex regulation of endometrial functions. Despite of the mass ‘omics’ data generated, only three in silico data-mining studies17, 31, 32 using previously published gene expression data have been published to date. Bhagwat et al. created a Human Gene Expression Endometrial Receptivity database (HGEx-ERdb) of 19,285 genes expressed in human endometrium, among which they identified 179 receptivity-associated genes32. Zhang et al. analysed raw data from three previous microarray studies33–35 and proposed 148 potential biomarkers of receptive endometrium17, while Tapia et al. integrated gene lists from seven previous microarray studies and presented a list of 61 endometrial receptivity biomarkers31. These three in silico analysis studies share only nine genes in common, highlighting the differences not only in in silico analysis approaches applied but also the great variation in study designs, analysis methods and data processing in published transcriptome studies. Clearly the mass of data generated within endometrial transcriptomics studies is under-explored, challenging investigators in future to analyse huge sets of data simultaneously in order to raise power, credibility and reliability of the findings.

The preferred method for gene expression meta-analysis requires analysis of raw expression datasets. However, such a thorough analysis is often not possible as a result of unavailability of raw data, which is partially the case in our meta-analysis. Variation in the number of gene transcripts known at a given moment together with the technological platform employed makes proper integration of raw datasets complicated. In addition, the limited sample size and noisiness of microarray data have resulted in inconsistency of biological conclusions36. In order to overcome these limitations, we directly analysed lists of differentially expressed genes from nine published studies involving a total of 164 endometrial biopsy samples from healthy women. Using a method that has been specifically designed for comparison of gene lists and identification of commonly overlapping genes in various studies, including recently published transcriptome studies in different ethnic groups30, 37, 38, we hope to provide an up-to-date meta-signature of endometrial receptivity biomarkers. Nevertheless, we have to bear in mind that with our approach, analysing the significantly differentially expressed gene lists, we could have missed the potential biomarker genes that were below statistical significance in individual studies but could become relevant in a meta-analysis.

The 57 genes identified in our meta-analysis could serve as the top-priority biomarkers of receptive phase endometrium in humans. Of special interest is SPP1, which was detected in all transcriptome studies that were included in our meta-analysis, together with ANXA4, CLDN4, DPP4, GPX3, MAOA, and PAEP, as they have also been identified as putative biomarkers of endometrial receptivity in the previous data-mining and review studies17, 19, 29, 31, 32.

Secreted phosphoprotein 1, SPP1, also known as osteopontin, is a secreted extracellular matrix (ECM) protein that binds to different cell-surface integrins to stimulate cell–cell and cell–ECM adhesion and communication (see Fig. 2), which play a part in the implantation process in various species39–41. It is generally accepted that SPP1 interacts with apically expressed integrins on the luminal endometrial epithelium and embryo trophectoderm to attach the conceptus to the endometrium39. Indeed, our cell type-specific RNA-seq validation analysis of endometrial epithelial and stromal cells demonstrates that SPP1 is up-regulated only in the epithelial cells (though in our setting we had a mixture of both luminal and glandular epithelial cells) and not in the stromal cells in the receptive phase endometrium (Fig. 5). Dysregulation of osteopontin in mid-secretory endometria of women with various reproductive disorders has been detected in several studies42–46. Further, our previous systems biology approach in investigation of the molecular networks in the implantation process revealed the involvement of osteopontin together with leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), apolipoprotein D (APOD) and leptin (LEP) pathways intertwining in a large network of cytokine–cytokine receptor interactions37.

Our meta-signature of mid-secretory endometrium highlights the importance of defence responses, specifically the inflammatory response (now recognized as a type of non-specific immune response), immunoglobulin-mediated immune responses (humoral immunity) and the complement (major mediator of innate immunity), and coagulation cascade pathway in receptive-phase endometrium. Immune responses, including the inflammatory response, play important roles in the pre- and peri-implantation period, and the up-regulation of genes involved in immune responses during the mid-secretory phase was corroborated in our meta-analysis and has also been highlighted in several previous studies20, 31, 47–49. In order to provide a hospitable environment for the embryo, the balance should be established between the maternal immune tolerance toward a semi-allogeneic implanting embryo and the protective anti-infectious mechanisms in the receptive-phase uterus47, 49. The innate immune system is the first line of defence, providing an immediate response through its ability to distinguish between ‘infectious non-self’ and ‘non-infectious self’ antigens50. Our meta-analysis highlights the importance of five genes involved in innate immunity, specifically in the complement system in mid-secretory endometrium, i.e. C1R, SERPING1, CD55, C4BPA and CFD, as shown in Fig. 2. CD55 (also known as DAF), for instance, is a complement regulatory protein with two suggested functions: protection of the embryo from maternal complement-mediated attack, and prevention of epithelial destruction resulting from increased complement expression at the time of implantation51. This protein has been found to be expressed at decreased levels in the endometria of women with recurrent pregnancy loss with antiphospholipid syndrome52. C4BPA is also suggested to have an embryo-protective role, where increased expression of this inhibitor of complement system activation could reduce the possibility of an uncontrolled complement attack on embryo31. Abnormally decreased levels of C4BPA expression in mid-secretory phase endometrium have been detected among women with endometriosis53, 54, implantation failure55 and unexplained recurrent abortion56.

The finding that a significant proportion of meta-signature genes are located in extracellular regions, including extracellular vesicles/exosomes, is intriguing. It is well known that the luminal epithelium with its extracellular area is the first maternal surface to interact with the trophoblast cells of the implanting embryo, but the involvement of extracellular vesicles in the implantation process is a new phenomenon57–61. Extracellular vesicles are membrane-bound complexes secreted from cells that act as messengers for cell–cell communication and signalling62. The origin of microvesicles and exosomes from endometrial epithelial cells in mid-secretory endometrium, the involvement of endometrial receptivity genes/proteins in exosomes and the uptake of extracellular vesicles by target blastocyst cells is depicted on Fig. 3. It has been proposed that extracellular vesicles, containing specific RNAs, including microRNAs and proteins, are released into the uterine cavity that could be transferred to either trophoblast cells or to endometrial epithelial cells, where they promote implantation57, 58, 62, 63. Twenty eight proteins from our endometrial receptivity-associated gene list have been experimentally detected in exosomes in humans (ExoCarta database). Our findings support the role of exosomes in endometrial receptivity and the subsequent embryo implantation, and indicate that further research into functional effects of extracellular vesicles in embryo-endometrium cross-talk is needed. Research on extracellular vesicles is a rapidly evolving and expanding field that could offer new opportunities regarding biomarkers of receptive endometrium and embryo implantation. Especially intriguing is the fact that extracellular vesicles have the potential in the development of non-invasive biomarkers and for thriving novel therapies to increase reproductive success.

The involvement of microRNAs in the mid-secretory endometrial functions has been shown by previous studies18. Further, studies on mice demonstrate that microRNAs are important in implantation and pregnancy, and the loss of Dicer (RNAse III endonuclease that is essential for the biogenesis of microRNAs) within uterus can compromise fertility64. MicroRNAs are non-coding RNA molecules acting as posttranscriptional regulators of gene expression and operate by either degrading or translationally repressing the target mRNAs65. There are now known over 2,000 annotated microRNAs in the human genome66, and since each microRNA may regulate hundreds of genes, it is estimated that microRNAs collectively regulate one third of genes in the genome67. Our prediction and subsequent validation analyses identified 19 down-regulated microRNAs in the mid-secretory phase endometria that resulted in up-regulation of 11 target mRNAs, because of reduced miRNA-mediated repression. Of special interest are miR-130b-3p and ANXA4, miR-548n and SPP1, miR-548ah-3p, miR-30c-1-3p and EFNA1, miR-30c-1-3p and ARID5B, and miR-449c-5p and DKK1 pairs, where the meta-signature gene was validated in two independent validation analyses. The importance of miR-30 family members, miR-30b and miR-30d, in endometrial receptivity have been highlighted in different studies58, 68–70, however the changed expression of miR-30c-1 has been detected so far in endometrial cancer patients71. In porcine endometrium the expression of miR-30c has been shown to increase during the gestational days, meaning that at the time of implantation this microRNA has been down-regulated when compared to placentation and mid-gestational times72. The increased expression of miR-130b and miR-449c-5p have been detected in endometrial cancer patients when compared to controls73, 74.

With our meta-analysis we highlight highly potential biomarkers of endometrial receptivity, but their molecular mechanisms in uterine physiology and pathophysiology remain to be investigated. Furthermore, to our knowledge, none of the molecular markers have yet been successfully applied in clinical therapeutic practice, including the highly promising molecule LIF15. Hence, the hunt for potentially informative and therapeutic markers of uterine receptivity continues. The era of looking for endometrial receptivity markers at other ‘omics’ levels has begun and it is to be hoped that this will result in further promising results (reviewed by refs 18 and 75). We believe that a novel approach for the future could hold in the microRNAs and/or exosome-based testing and therapeutic strategy for improving endometrial receptivity. Regardless of the biomarker sets chosen to identify receptive endometrium, all will need extensive validation before their clinical utility can be proven. Several of our meta-signature genes have already been validated on mRNA and/or protein level in individual marker and/or transcriptome studies (summarised in Table 2).

In conclusion, we present a meta-analysis approach allowing convergence and dissection of heterogeneous mRNA expression profiling datasets of receptive phase endometrium. We identified a meta-signature of endometrial receptivity composed of 57 genes, where 39 of these genes were experimentally confirmed in two separate datasets. These meta-signature genes highlight the importance of immune responses, the complement cascade pathway and the involvement of exosomes in mid-secretory endometrial functions, and could serve as promising biomarkers of endometrial receptivity and achieving a pregnancy.

Methods

Systematic search of the literature

A systematic review of the literature in PubMed and Scopus was independently conducted up to June 2016 by two researchers (S.A. and M.S.). MeSH terms ‘embryo implantation’, ‘endometrium’ and ‘gene expression’ were used. The reference lists of review articles and relevant studies were hand-searched to identify other potentially eligible studies. No language or any other restrictions were applied. Details of the protocol for this systematic review were registered on PROSPERO and can be accessed at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID = CRD42016041509.

Abstracts of all articles identified through the search were read for selection of eligible studies. The full text of each eligible article was carefully evaluated. Only original experimental studies published in English and concerning the endometrial transcriptome (using microarray or RNA-seq techniques) in healthy women in the mid-secretory phase vs. the ‘pre-receptive’ phase (proliferative and/or early secretory phase) were included for final analysis. Endometrial transcriptome analysis in connection with any pathological condition, such as infertility, endometriosis, adenomyosis and cancer was excluded. In addition, transcriptome analyses focussing on different endometrial tissue-compartments separately were not included in the meta-analysis.

Analysis settings

The lists of genes differentially expressed in mid-secretory vs. ‘pre-receptive’-phase endometrium were extracted from the publications. Where the gene lists were not available, the authors were contacted directly. In transcriptome array studies, if the probe information for a dataset was available, probes were annotated to corresponding ENTREZ IDs using respective Bioconductor 3.1 Affymetrix probe annotation package, in studies using Affymetrix microarray platform. If probe-level data was not available, gene lists were converted to ENTREZ IDs by using the DAVID Gene ID Conversion Tool (DAVID Bioinformatics Resources). Genes reported in a study by Hu et al. that involved Illumina RNA-seq platform38 were standardised to ENTREZ IDs by using the BiomaRt package and ENSEMBL v.75 database. For one study33, the differentially expressed probe lists were acquired by reanalysing the data stored in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE6364. We used GEO2R web tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/info/geo2r.html) with default options for differential analysis and gene list acquisition (false discovery rate, FDR < 0.05; fold change, FC > 2.0). Probes not annotated by ENTREZ IDs were removed from subsequent analyses.

Subsequently, lists of up- and down-regulated genes were ranked by their fold changes. In cases of multiple probes detecting the same gene, only the probe with the largest absolute fold change was used for list construction.

Meta-analysis

The robust rank aggregation algorithm (RRA package v.1.1) was used for meta-analysis of the ranked gene lists24. To assess full gene list sizes, the number of detectable gene ENTREZ IDs was used for each array platform and all ENTREZ IDs from BioMart v.75 were used for the RNA-seq study38. For correcting for multiple testing, we used a strict Bonferroni threshold by multiplying all P-values by the maximal number of elements in all input lists. In our case this involved the data published by Hu et al.38, where the total number of ENTREZ IDs available in ENSEMBL v.75 (39,030) was used as the total number of tests. All lists used in the analysis reflect expression in the mid-secretory group compared with another group (proliferative or early-secretory phase).

Enrichment analysis

Enrichment analyses for Gene Ontology (GO) terms and biological pathways (KEGG and Reactome) were carried out by using the g:Profiler web tool (biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/)76, 77. This software was chosen over other enrichment analysis tools as it is up-to-date (updated in May 2016 to Ensembl 84 and Ensembl Genomes 31) and it provides a compact graphical output. The obtained results were corrected for multiple testing by using the g:Profiler tailor-made algorithm g:SCS, which has been shown to provide a better threshold between significant and non-significant results than (commonly used) Bonferroni correction or the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate76.

In silico analysis of potential microRNAs regulating meta-signature genes

MicroRNA target prediction was performed using three different algorithms – DIANA microT-CDS, TargetScan 7.0 and miRanda v3.3a. In DIANA microT-CDS78 and TargetScan 7.079 precomputed prediction results were downloaded from their respective websites (diana.imis.athena-innovation.gr/DianaTools/index.php?r = microT_CDS/index; www.targetscan.org/cgi-bin/targetscan/data_download.cgi?db = vert_70). DIANA microT-CDS utilises ENSEMBL v69 transcriptome and miRBase v18 for the prediction, whereas TargetScan 7.0 uses ENSEMBL v75 and miRBase v2180. miRanda v3.3a binary81 was downloaded from http://www.microrna.org/microrna/getDownloads.do and used for the target prediction with ENSEMBL v75 3′UTRs and miRBase v21 mature sequences as an input. The algorithm was used with default settings: Gap Open Penalty: −9.0, Gap Extend Penalty: −4.0, Score Threshold: 140.0, Energy Threshold: 1.0 kcal/mol and Scaling Parameter: 4.0. miRBase internal IDs were used to standardise microRNA names between different miRBase versions.

For additional support to in silico target predictions, we used database harbouring experimental data about mammalian microRNA binding sites. Therefore, Argonaute (AGO1, AGO2, AGO3 and AGO4) HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP datasets for human cell lines were downloaded from StarBase v.2.082 website in the BED format and overlaid with predicted microRNA target sites (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/download.php).

Validation of meta-signature genes and predicted microRNAs in the independent sample sets

We validated the meta-signature genes in our two independent sample sets from NOTED project (EU-FP7 Eurostars Programme, EU41564) and SARM project (EU-FP7, IAPP, EU324509). The studies were approved by the local Research Ethics Committees of the University of Tartu and Instituto Valenciano de Infertilidad. An informed consent was signed by all women who agreed to participate in the study, and all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

The detailed description of the study participants and RNA-seq analysis within NOTED project is described in the Supplementary Material. Briefly, 20 healthy fertile women provided endometrial biopsy samples in the early secretory phase (2 days after the luteinizing hormone (LH) peak, LH+2) and in the mid-secretory phase of the menstrual cycle (LH+8) within the same natural cycle. Total mRNA transcriptome and microRNA profile analysis from the same biopsy samples were performed with the RNA-seq method. Differential expression was tested using the edgeR statistical package. Up-regulation was defined as statistically significantly (FDR corrected p-value < 0.05) higher expression (expressed as ‘counts per million reads’, CPM) in the mid-secretory phase samples, whereas down-regulation was defined as statistically significantly lower expression in the mid-secretory samples. The primary RNA-seq data are available in the public database Gene Expression Omnibus (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE98386.

The other independent set of validation was carried out in additional 16 healthy fertile women within SARM project, where cell type-specific RNA-seq on endometrial samples was performed, with separated epithelial and stromal cells. Briefly, endometrial biopsies were collected from 16 healthy fertile women on two different time points within the natural cycle, LH+2 and LH+8. Single cells from endometrial biopsy samples were separated, epithelial cells were labelled with fluorochrome-conjugated mouse anti-human CD9 monoclonal antibody and stromal cells were simultaneously labelled with fluorochrome-conjugated mouse anti-human CD13 monoclonal antibody, followed by flow cytometric analysis and FACS cell sorting. Bulk-RNA full transcriptome analysis of FACS sorted endometrial epithelial and stromal cells was performed with the RNA-seq method, following the single-cell tagged reverse transcription (STRT) protocol with modifications83. Differential expression was tested using the edgeR statistical package. Up-regulation was defined as statistically significantly (FDR corrected p-value < 0.05) higher expression (expressed as ‘normalised read counts’) in the mid-secretory phase samples, whereas down-regulation was defined as statistically significantly lower expression in the mid-secretory samples. The primary RNA-seq data are available in the public database Gene Expression Omnibus (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE97929. Detailed protocol of the sample collection, processing, and analysis is described in the Supplementary Material.

Further validation of the endometrial receptivity signature genes DDX52, DYNLT3, C1R and APOD on NOTED and SARM project samples using real-time PCR is described in the Supplementary Material.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a Marie Curie post-doctoral fellowship (FP7, no. 329812, NutriOmics); grant from University of Granada (Incorporación de jóvenes doctores); Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (grant IUT34-16); Enterprise Estonia (grant EU48695); the EU-FP7 Eurostars program (grant NOTED, EU41564); the EU-FP7 Marie Curie Industry-Academia Partnerships and Pathways (IAPP, grant SARM, EU324509); Horizon 2020 innovation programme (WIDENLIFE, 692065) and the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Author Contributions

Performed thorough literature search: S.A., M.S. Performed meta-analysis: U.V. Provided additional data for meta-analysis: L.A., P.G.L., K.G.-D., L.G., C.S. Performed additional statistical analyses: S.A., M.K., P.A., T.L.-P., V.K. Comprehensive validation experiments: M.K., M.S., T.L.-P., Merli S., A.V-M., K.K, A.S. Wrote the main body of the manuscript: S.A., M.K., U.V. Contributed to manuscript writing and editing: P.A., M.S., T.L.-P., V.K., Merli S., A.V.-M., K.K., L.A., P.G.L., K.G.-D., L.G., C.S., A.S. Authors have declared no competing interests.

Competing Interests

Prof. Carlos Simón is the Chief Scientific Officer of Igenomiz, a Biotec Company that commercialize the ERA test. All the rest of the authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-10098-3

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR. Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1796–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macklon NS, Stouffer RL, Giudice LC, Fauser BC. The science behind 25 years of ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:170–207. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cha, J., Vilella, F., Dey, S. & Simón, C. In Ten Critical Topics in Reproductive Medicine 44–48 (Science/AAAS, Washington DC, 2013).

- 4.Edwards RG. Clinical approaches to increasing uterine receptivity during human implantation. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(Suppl 2):60–66. doi: 10.1093/humrep/10.suppl_2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Margalioth EJ, Ben-Chetrit A, Gal M, Eldar-Geva T. Investigation and treatment of repeated implantation failure following IVF-ET. Hum. Reprod. 2006;21:3036–43. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon A, Laufer N. Repeated implantation failure: clinical approach. Fertil. Steril. 2012;97:1039–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiz-Alonso, M. et al. The endometrial receptivity array as diagnosis and personalized embryo transfer as treatment for patients with receptive implantation failure. Fertil Steril in press (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Teklenburg G, Salker M, Heijnen C, Macklon NS, Brosens JJ. The molecular basis of recurrent pregnancy loss: impaired natural embryo selection. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16:886–895. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teklenburg G, et al. Natural selection of human embryos: decidualizing endometrial stromal cells serve as sensors of embryo quality upon implantation. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salker MS, et al. Disordered IL-33/ST2 activation in decidualizing stromal cells prolongs uterine receptivity in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noyes RW, Hertig AT, Rock J. Dating the endometrial biopsy. Fertil Steril. 1950;1:3–25. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)30062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noyes RW, Hertig AT, Rock J. Dating the endometrial biopsy. Am J Obs. Gynecol. 1975;122:262–263. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(16)33500-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coutifaris C, et al. Histological dating of timed endometrial biopsy tissue is not related to fertility status. Fertil. Steril. 2004;82:1264–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray MJ, et al. A critical analysis of the accuracy, reproducibility, and clinical utility of histologic endometrial dating in fertile women. Fertil. Steril. 2004;81:1333–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinsden PR, Alam V, de Moustier B, Engrand P. Recombinant human leukemia inhibitory factor does not improve implantation and pregnancy outcomes after assisted reproductive techniques in women with recurrent unexplained implantation failure. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1445–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lessey BA. Assessment of endometrial receptivity. Fertil. Steril. 2011;96:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.07.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang D, Sun C, Ma C, Dai H, Zhang W. Data mining of spatial-temporal expression of genes in the human endometrium during the window of implantation. Reprod. Sci. 2012;19:1085–1098. doi: 10.1177/1933719112442248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altmäe S, et al. Guidelines for the design, analysis and interpretation of ‘omics’ data: focus on human endometrium. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2014;20:12–28. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horcajadas JA, Pellicer A, Simon C. Wide genomic analysis of human endometrial receptivity: new times, new opportunities. Hum Reprod Updat. 2007;13:77–86. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altmäe S, et al. Endometrial gene expression analysis at the time of embryo implantation in women with unexplained infertility. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16:178–187. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz-Alonso M, Blesa D, Simon C. The genomics of the human endometrium. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1822:1931–1942. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulbrich SE, Groebner AE, Bauersachs S. Transcriptional profiling to address molecular determinants of endometrial receptivity–lessons from studies in livestock species. Methods. 2013;59:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aghajanova L, Hamilton AE, Giudice LC. Uterine receptivity to human embryonic implantation: histology, biomarkers, and transcriptomics. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolde R, Laur S, Adler P, Vilo J. Robust rank aggregation for gene list integration and meta-analysis. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:573–80. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otsuka AY, Andrade PM, Villanova FE, Borra RC, Silva IDCG. Human endometrium mRNA profile assessed by oligonucleotide three-dimensional microarray. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2007;23:527–34. doi: 10.1080/09513590701550221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haouzi D, et al. Identification of new biomarkers of human endometrial receptivity in the natural cycle. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:198–205. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ponnampalam AP, Weston GC, Trajstman AC, Susil B, Rogers PAW. Molecular classification of human endometrial cycle stages by transcriptional profiling. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2004;10:879–93. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong X-M, Lin X-N, Song T, Liu L, Zhang S. Calcium-binding protein S100P is highly expressed during the implantation window in human endometrium. Fertil. Steril. 2010;94:1510–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tseng LH, et al. Genome-based expression profiling as a single standardized microarray platform for the diagnosis of endometrial disorder: an array of 126-gene model. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diaz-Gimeno P, et al. A genomic diagnostic tool for human endometrial receptivity based on the transcriptomic signature. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(50–60):60–15. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tapia A, Vilos C, Marin JC, Croxatto HB, Devoto L. Bioinformatic detection of E47, E2F1 and SREBP1 transcription factors as potential regulators of genes associated to acquisition of endometrial receptivity. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2011;9 doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhagwat SR, et al. Endometrial receptivity: a revisit to functional genomics studies on human endometrium and creation of HGEx-ERdb. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talbi S, et al. Molecular phenotyping of human endometrium distinguishes menstrual cycle phases and underlying biological processes in normo-ovulatory women. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1097–1121. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burney RO, et al. Gene expression analysis of endometrium reveals progesterone resistance and candidate susceptibility genes in women with endometriosis. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3814–3826. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hever A, et al. Human endometriosis is associated with plasma cells and overexpression of B lymphocyte stimulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12451–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703451104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Võsa U, et al. Meta-analysis of microRNA expression in lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;132:2884–2893. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altmäe S, et al. Research resource: interactome of human embryo implantation: identification of gene expression pathways, regulation, and integrated regulatory networks. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012;26:203–217. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu S, et al. Transcriptomic changes during the pre-receptive to receptive transition in human endometrium detected by RNA-Seq. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99:E2744–53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Bazer FW. Osteopontin: a leading candidate adhesion molecule for implantation in pigs and sheep. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014;5 doi: 10.1186/2049-1891-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang Y-J, Forbes K, Carver J, Aplin JD. The role of the osteopontin-integrin αvβ3 interaction at implantation: functional analysis using three different in vitro models. Hum. Reprod. 2014;29:739–49. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu N, Zhou C, Chen Y, Zhao J. The involvement of osteopontin and β3 integrin in implantation and endometrial receptivity in an early mouse pregnancy model. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013;170:171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DuQuesnay R, et al. Infertile women with isolated polycystic ovaries are deficient in endometrial expression of osteopontin but not alphavbeta3 integrin during the implantation window. Fertil. Steril. 2009;91:489–99. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casals G, et al. Osteopontin and alphavbeta3 integrin as markers of endometrial receptivity: the effect of different hormone therapies. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2010;21:349–59. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casals G, et al. Expression pattern of osteopontin and αvβ3 integrin during the implantation window in infertile patients with early stages of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2012;27:805–13. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.D’Amico F, et al. Expression and localisation of osteopontin and prominin-1 (CD133) in patients with endometriosis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013;31:1011–6. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao Y, et al. Expression of integrin β3 and osteopontin in the eutopic endometrium of adenomyosis during the implantation window. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013;170:419–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giudice LC. Microarray expression profiling reveals candidate genes for human uterine receptivity. Am. J. Pharmacogenomics. 2004;4:299–312. doi: 10.2165/00129785-200404050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giudice LC. Application of functional genomics to primate endometrium: insights into biological processes. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2006;4(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-4-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haller-Kikkatalo K, Altmäe S, Tagoma A, Uibo R, Salumets A. Autoimmune activation toward embryo implantation is rare in immune-privileged human endometrium. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2014;32:376–84. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1376356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Janeway CA, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Franchi A, Zaret J, Zhang X, Bocca S, Oehninger S. Expression of immunomodulatory genes, their protein products and specific ligands/receptors during the window of implantation in the human endometrium. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2008;14:413–421. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gan029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Francis J, et al. Impaired expression of endometrial differentiation markers and complement regulatory proteins in patients with recurrent pregnancy loss associated with antiphospholipid syndrome. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2006;12:435–442. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kao LC, et al. Expression profiling of endometrium from women with endometriosis reveals candidate genes for disease-based implantation failure and infertility. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2870–2881. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Isaacson KB, Coutifaris C, Garcia CR, Lyttle CR. Production and secretion of complement component 3 by endometriotic tissue. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1989;69:1003–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-69-5-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tapia A, et al. Differences in the endometrial transcript profile during the receptive period between women who were refractory to implantation and those who achieved pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:340–351. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee J, et al. Differentially expressed genes implicated in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007;39:2265–2277. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ng YH, et al. Endometrial exosomes/microvesicles in the uterine microenvironment: a new paradigm for embryo-endometrial cross talk at implantation. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vilella F, et al. Hsa-miR-30d, secreted by the human endometrium, is taken up by the pre-implantation embryo and might modify its transcriptome. Development. 2015;142:3210–3221. doi: 10.1242/dev.124289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Machtinger, R., Laurent, L. C. & Baccarelli, A. A. Extracellular vesicles: roles in gamete maturation, fertilization and embryo implantation. Hum Reprod Updat, doi:10.1093/humupd/dmv055 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Saadeldin M, Oh H, Lee B. Embryonic – maternal cross-talk via exosomes: potential implications. Stem Cells Cloning Adv. Appl. 2015;8:103–107. doi: 10.2147/SCCAA.S84991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Evans, J. et al. Fertile ground: human endometrial programming and lessons in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol, doi:10.1038/nrendo.2016.116 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Tannetta, D., Dragovic, R., Alyahyaei, Z. & Southcombe, J. Extracellular vesicles and reproduction-promotion of successful pregnancy. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 1–16, doi:10.1038/cmi.2014.42 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Burns G, et al. Extracellular vesicles in luminal fluid of the ovine uterus. PLoS One. 2014;9:15–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luense LJ, Carletti MZ, Christenson LK. Role of Dicer in female fertility. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;20:265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hammond SM. An overview of microRNAs. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015;87:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lewis BP, et al. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sha AG, et al. Genome-wide identification of micro-ribonucleic acids associated with human endometrial receptivity in natural and stimulated cycles by deep sequencing. Fertil. Steril. 2011;96:150–155 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Altmäe S, et al. MicroRNAs miR-30b, miR-30d, and miR-494 Regulate Human Endometrial Receptivity. Reprod. Sci. 2013;20:308–317. doi: 10.1177/1933719112453507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuokkanen S, et al. Genomic profiling of microRNAs and messenger RNAs reveals hormonal regulation in microRNA expression in human endometrium. Biol. Reprod. 2010;82:791–801. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.081059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boren T, et al. MicroRNAs and their target messenger RNAs associated with endometrial carcinogenesis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008;110:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Su L, et al. Expression patterns of microRNAs in porcine endometrium and their potential roles in embryo implantation and placentation. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chung TKH, et al. Dysregulated microRNAs and their predicted targets associated with endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma in Hong Kong women. Int. J. cancer. 2009;124:1358–65. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu W, Lin Z, Zhuang Z, Liang X. Expression profile of mammalian microRNAs in endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2009;18:50–5. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328305a07a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Simon C, Sakkas D, Gardner DK, Critchley HOD. Biomarkers in reproductive medicine: the quest for new answers. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2015;21:695–697. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reimand J, Kull M, Peterson H, Hansen J, Vilo J. g:Profiler–a web-based toolset for functional profiling of gene lists from large-scale experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W193–200. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reimand J, Arak T, Vilo J. G:Profiler - A web server for functional interpretation of gene lists (2011 update) Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Paraskevopoulou MD, et al. DIANA-microT web server v5.0: service integration into miRNA functional analysis workflows. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W169–73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Agarwal, V., Bell, G. W., Nam, J.-W. & Bartel, D. P. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D68–73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Betel D, Koppal A, Agius P, Sander C, Leslie C. Comprehensive modeling of microRNA targets predicts functional non-conserved and non-canonical sites. Genome Biol. 2010;11 doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li J-H, Liu S, Zhou H, Qu L-H, Yang J-H. starBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D92–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krjutškov K, et al. Single-cell transcriptome analysis of endometrial tissue. Hum. Reprod. 2016;31:844–53. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Raposo, G. & Stoorvogel, W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. 200, 373–383 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Kao LC, et al. Global gene profiling in human endometrium during the window of implantation. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2119–2138. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Borthwick JM, et al. Determination of the transcript profile of human endometrium. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:19–33. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carson DD, et al. Changes in gene expression during the early to mid-luteal (receptive phase) transition in human endometrium detected by high-density microarray screening. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:871–879. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.9.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Riesewijk A, et al. Gene expression profiling of human endometrial receptivity on days LH+2 versus LH+7 by microarray technology. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:253–264. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mirkin S, et al. In search of candidate genes critically expressed in the human endometrium during the window of implantation. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2104–2117. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Julkunen M, et al. Secretory endometrium synthesizes placental protein 14. Endocrinology. 1986;118:1782–6. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-5-1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Allegra A, et al. Endometrial expression of selected genes in patients achieving pregnancy spontaneously or after ICSI and patients failing at least two ICSI cycles. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2012;25:481–91. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Apparao KB, et al. Osteopontin and its receptor alphavbeta(3) integrin are coexpressed in the human endometrium during the menstrual cycle but regulated differentially. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:4991–5000. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang D, Lei C, Zhang W. Up-regulated monoamine oxidase in the mouse uterus during the peri-implantation period. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011;284:861–866. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1765-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Macdonald LJ, et al. Prokineticin 1 induces Dickkopf 1 expression and regulates cell proliferation and decidualization in the human endometrium. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2011;17:626–36. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gar031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Serafini P, et al. Protein profile of the luteal phase endometrium by tissue microarray assessment. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2009;25:587–92. doi: 10.1080/09513590902972018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kitaya K, et al. IL-15 expression at human endometrium and decidua. Biol. Reprod. 2000;63:683–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.3.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nogawa Fonzar-Marana RR, et al. Expression of complement system regulatory molecules in the endometrium of normal ovulatory and hyperstimulated women correlate with menstrual cycle phase. Fertil. Steril. 2006;86:758–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ohta T, et al. Expression profiles of perforin, granzyme B and granulysin genes during the estrous cycle and gestation in the bovine endometrium. Anim. Sci. J. 2014;85:763–9. doi: 10.1111/asj.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ugur Y, Cakar AN, Beksac MS, Dagdeviren A. Activation antigens during the proliferative and secretory phases of endometrium and early-pregnancy decidua. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2006;62:66–74. doi: 10.1159/000092375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dolanbay EG, et al. Expression of trophinin and dipeptidyl peptidase IV in endometrial co-culture in the presence of an embryo: A comparative immunocytochemical study. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016;13:3961–8. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ponnampalam AP, Rogers PAW. Cyclic changes and hormonal regulation of annexin IV mRNA and protein in human endometrium. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2006;12:661–9. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fujiwara H, et al. Human endometrial epithelial cells express ephrin A1: possible interaction between human blastocysts and endometrium via Eph-ephrin system. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87:5801–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Germeyer A, et al. Cell-type specific expression and regulation of apolipoprotein D and E in human endometrium. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013;170:487–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Evans-Hoeker E, et al. Endometrial BCL6 Overexpression in Eutopic Endometrium of Women With Endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 2016;23:1234–41. doi: 10.1177/1933719116649711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yang S, et al. Regulation of aromatase P450 expression in endometriotic and endometrial stromal cells by CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins (C/EBPs): decreased C/EBPbeta in endometriosis is associated with overexpression of aromatase. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87:2336–45. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tajima M, Harada T, Ishikawa T, Iwahara Y, Kubota T. Augmentation of arginase II expression in the human endometrial epithelium in the secretory phase. J. Med. Dent. Sci. 2012;59:75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Das S, Vince GS, Lewis-Jones I, Bates MD, Gazvani R. The expression of human alpha and beta defensin in the endometrium and their effect on implantation. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2007;24:533–9. doi: 10.1007/s10815-007-9173-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Keator CS, Mah K, Ohm L, Slayden OD. Estrogen and progesterone regulate expression of the endothelins in the rhesus macaque endometrium. Hum. Reprod. 2011;26:1715–28. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rutanen E-M, Gonzalez E, Said J, Braunstein GD. Immunohistochemical localization of the insulinlike growth factor binding protein-1 in female reproductive tissues by monoclonal antibodies. Endocr. Pathol. 1991;2:132–138. doi: 10.1007/BF02915453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sedlmayr P, et al. Localization of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in human female reproductive organs and the placenta. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2002;8:385–91. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Deng L, et al. Expression and clinical significance of annexin A2 and human epididymis protein 4 in endometrial carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;34 doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0208-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Altmäe S, Kallak TK, Friden B, Stavreus-Evers A. Variation in Hyaluronan-Binding Protein 2 (HABP2) Promoter Region is Associated With Unexplained Female Infertility. Reprod Sci. 2011;18:485–492. doi: 10.1177/1933719110388849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mobasheri A, Wray S, Marples D. Distribution of AQP2 and AQP3 water channels in human tissue microarrays. J. Mol. Histol. 2005;36:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10735-004-2633-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Klimek M, et al. Cycle dependent expression of endometrial metallothionein. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2005;26:663–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Malette B, et al. Large scale validation of human N-myc downstream-regulated gene (NDRG)-1 expression in endometrium during the menstrual cycle. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2003;9:671–9. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kottawatta KSA, et al. MicroRNA-212 Regulates the Expression of Olfactomedin 1 and C-Terminal Binding Protein 1 in Human Endometrial Epithelial Cells to Enhance Spheroid Attachment In Vitro. Biol. Reprod. 2015;93 doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.131334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.