Abstract

Neutrophils play important roles in innate immunity and are mainly dependent on various enzyme-containing granules to kill engulfed microorganisms. Zebrafish nephrosin (npsn) is specifically expressed in neutrophils; however, its function is largely unknown. Here, we generated an npsn mutant (npsnsmu5) via CRISPR/Cas9 to investigate the in vivo function of Npsn. The overall development and number of neutrophils remained unchanged in npsn-deficient mutants, whereas neutrophil antibacterial function was defective. Upon infection with Escherichia coli, the npsnsmu5 mutants exhibited a lower survival rate and more severe bacterial burden, as well as augmented inflammatory response to challenge with infection when compared with wild-type embryos, whereas npsn-overexpressing zebrafish exhibited enhanced host defence against E. coli infection. These findings demonstrated that zebrafish Npsn promotes host defence against bacterial infection. Furthermore, our findings suggested that npsn-deficient and -overexpressing zebrafish might serve as effective models of in vivo innate immunity.

Keywords: neutrophil, nephrosin, infection, zebrafish

1. Introduction

Neutrophils constitute the most abundant circulating leukocytes and play important roles in the innate immune system, with essential functions related to host defence against invading pathogens [1]. Upon host infection, neutrophils are typically the first responders recruited from haematopoietic tissue and travel through the vasculature to infected sites [2]. Neutrophils primarily eliminate pathogens in two ways: (i) secretion of cytokines and chemokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1b [3], IL-18 [4] and IL-37 [5], to recruit and activate additional phagocytes to the infection site; and (ii) phagocytosing microbes, primarily dependent on their granules [6]. Neutrophils contain the following four types of granules: azurophil (also known as primary) granules, specific (also known as secondary) granules, gelatinase (also known as tertiary) granules and secretory granules [7]. These granules destroy pathogens by either activating membrane-bound NADPH oxidase to generate reactive oxygen species [8,9] or through proteolysis to destroy the integrity of bacterial membranes or cytoderms [10,11]. However, the function of these granules has mainly been studied in vitro, leaving many of their in vivo functions unknown.

Nephrosin (Npsn) was first discovered in the lymphohaematopoietic tissues of Cyprinus carpio and is a zinc metalloendopeptidase belonging to the astacin family [12], which exhibit diverse biological functions including protein digestion, dorsal/ventral determination and morphogenesis [13]. Carp Npsn exhibits greater than 50% sequence identity to medaka-hatching enzymes, although there was no npsn expression observed in carp hatching liquid, indicating that Npsn is not a hatching-enzyme analogue [12]. Another study found that npsn was specifically expressed at zebrafish haematopoietic sites [14], and most npsn-positive cells express granulocytic markers [14], suggesting that zebrafish Npsn might be a granzyme in granulocytes. However, the function of Npsn in granulocytes remains unknown.

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a powerful vertebrate model for the study of infectious disease. Despite its traditional advantages, including high fecundity, external development and convenient tools capable of manipulating gene expression, zebrafish offer many unique advantages for studying neutrophils and pathogens. First, the vertebrate innate immune system is highly conserved between zebrafish and mammals, including their containing macrophages [15], neutrophils [16,17] and complements [18]. Additionally, their establishment of a functional adaptive immune system is delayed until approximately 3 weeks post-fertilization [19]. This distinction in immune development makes zebrafish embryos and larvae ideally suited to study host innate immune response to bacterial pathogens [20,21], as well as functions and behaviours of neutrophils in microbe infection [22,23]. Second, the process of granulocytopoiesis, involving origination from haematopoietic stem cells and development into myeloblasts and mature granulocytes, is conserved between mammals and zebrafish [24,25]. Additionally, zebrafish models allow the unique ability to study host–pathogen interactions in real time due to the transparency of zebrafish embryos and the wide range of available fluorescence-analysis tools [26]. Therefore, the zebrafish represents an ideal system for studying the function of Npsn in inflammatory response.

In this study, we used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to obtain an npsn-deficient mutant (npsnsmu5) in order to investigate the in vivo function of Npsn. The mutant showed no altered neutrophil number, but exhibited deficient antibacterial function. Upon infection with Escherichia coli, the npsnsmu5 mutants exhibited a lower survival rate and more severe bacterial burden, as well as increased inflammatory response to challenge with infection, when compared with wild-type (WT) embryos. Additionally, we observed that npsn overexpression enhanced host defence against E. coli infection. Our findings suggested that Npsn is crucial for host defence against bacterial infection, and that npsn-deficient and overexpressing zebrafish might serve as effective models of in vivo innate immunity.

2. Results

2.1. Zebrafish npsn is expressed in neutrophils

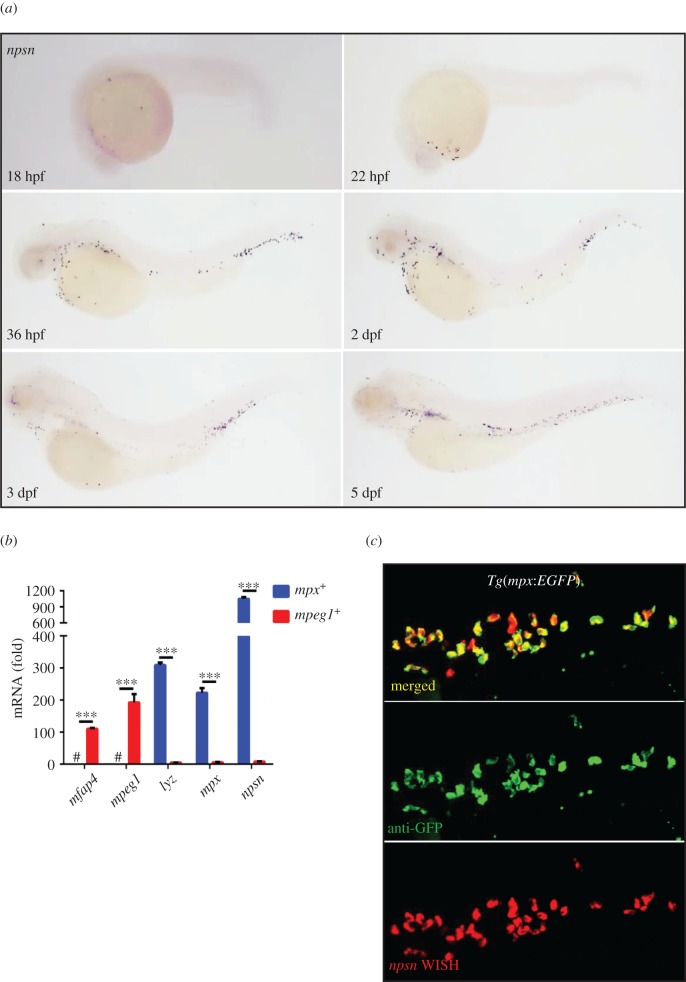

To determine the role of Npsn in embryogenesis, we examined the temporal and spatial expression of npsn by whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) analysis. At 18 h post-fertilization (hpf), we observed that npsn was initially expressed in the rostral blood island, the location of myelopoiesis in primitive haematopoiesis, then spread widely across the site of haematopoiesis (figure 1a), which was consistent with findings from a previous study [14]. To identify npsn expression in myeloid cells, fluorescent cells sorted from neutrophil-specific Tg(mpx:EGFP) and macrophage-specific Tg(mpeg1:EGFP) zebrafish lines were used to detect the relative expression of npsn in neutrophils and macrophages, respectively. Our results showed that npsn was highly expressed in neutrophils and relatively much lower in macrophages after adjustment for GFP− cells (figure 1b). Co-staining with anti-GFP and npsn WISH analysis of Tg(mpx:EGFP) confirmed that most npsn+ cells could be co-stained with mpx+ neutrophils (figure 1c), demonstrating neutrophil-specific expression.

Figure 1.

Zebrafish npsn is predominantly expressed in neutrophils. (a) The expression pattern of npsn during zebrafish embryogenesis was initially observed at the rostral blood island at 18 hpf, followed by widespread expression across the site of haematopoiesis in zebrafish. (b) Higher expression of npsn in neutrophils when compared with macrophages. Fluorescent cells were sorted from Tg(mpx:EGFP) and Tg(mpeg1:EGFP), and qRT-PCR was performed to detect the npsn expression, which was highly expressed in neutrophils relative to levels observed in macrophages following adjustment for GFP− cells. Macrophage markers (mfap4 and mpeg1) and neutrophil markers (lyz and mpx) were used as indicators to test the purity of the sorted macrophages and neutrophils; ***p < 0.001. #, undetected. (Mean ± s.e.m., n ≥ 200 per experiment, triplicated). (c) Co-staining for npsn mRNA in mpx+ cells at the posterior blood island (PBI) in Tg(mpx:EGFP) embryos. Double staining for anti-GFP and npsn WISH was performed in Tg(mpx:EGFP) cells at 3 dpf. Most mpx+ neutrophils also expressed npsn mRNA in the PBI.

Based on this expression pattern, we cloned the npsn promoter to drive GFP expression in order to generate a zebrafish reporter allowing visualization of npsn+ cells. We isolated a 2 kb DNA fragment upstream of the npsn-translation start site in the promoter region to drive GFP expression in the Tol2 vector (referred to as pTol2-npsn-EGFP) (electronic supplementary material, figure S1a). The pTol2-npsn-EGFP construct was injected into one-cell-stage WT embryos, followed by screening for founders capable of producing offspring exhibiting GFP expression (referred to as Tg(npsn:EGFP)smu7) at developing haematopoietic sites (electronic supplementary material, figure S1b). To determine whether GFP+ cells could report npsn expression, we performed double fluorescent staining for GFP and npsn WISH, with results showing that the majority of the fluorescent signals were co-located (electronic supplementary material, figure S1c). Inter-crossing the Tg(npsn:EGFP)smu7 line with the Tg(lyz:DsRed) line indicated that most of the npsn+ cells overlapped with lyz+ cells in the haematopoietic regions, including the thymus (electronic supplementary material, figure S1d, 1d′), aorta–gonad–mesonephros (electronic supplementary material, figure S1e,1e′) and posterior blood island (PBI) (electronic supplementary material, figure S1f,1f′). To compare the specificity of Tg(npsn:EGFP)smu7 and Tg(mpx:EGFP), we sorted the GFP+ cells, respectively, by flow cytometry, with quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) results showing that the expression levels of neutrophil markers (mpx, lyz and npsn) were significantly higher in npsn+ cells, whereas levels of macrophage markers (mfap4 and mpeg1) were lower (electronic supplementary material, figure S1g), suggesting that the npsn promoter drove expression specifically in neutrophils. Taken together, these findings suggested that npsn was predominantly expressed in neutrophils rather than in macrophages.

2.2. Generation and identification of npsn-deficient zebrafish

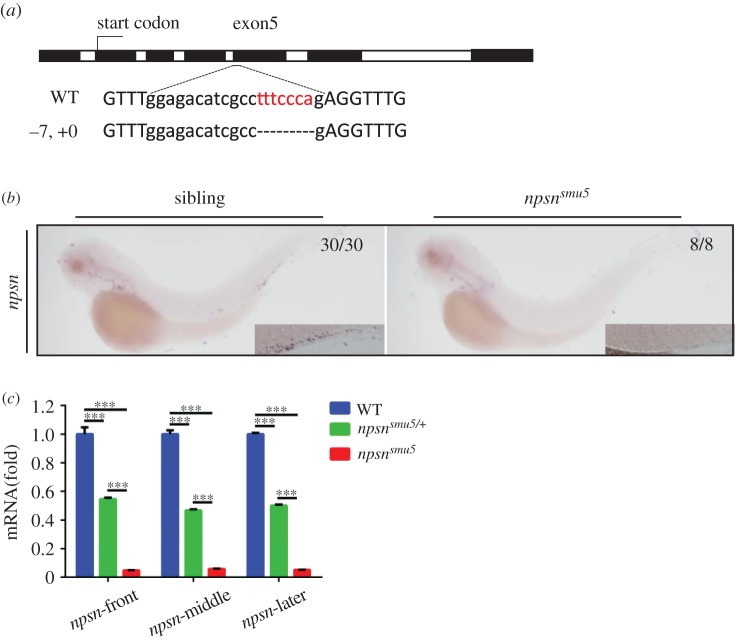

To characterize the in vivo function of Npsn in zebrafish neutrophils, we generated npsn-knockout lines utilizing the CRISPR/Cas9 system. We obtained two frameshift mutations, with one (−7, +0) in exon5-Cas9 (referred to as npsnsmu5) (figure 2a) and the other (−0, +1) in exon6-Cas9 (referred as npsnsmu6) (electronic supplementary material, figure S2a). We then performed WISH to detect the expression of npsn mRNA. Interestingly, npsn expression was significantly decreased in npsnsmu5 and npsnsmu6 embryos at various stages of development (24 hpf, 36 hpf, 2 days post-fertilization (2 dpf) and 3 dpf) (figure 2b and electronic supplementary material, figure S2b,c). Levels of npsn mRNA exhibited similar downregulation to 5% in homozygous npsnsmu5 embryos, with a 50% decrease in the heterozygote (figure 2c), suggesting that npsn mRNA may undergo full-scale degradation in npsnsmu5 embryos, with reductions in npsn mRNA possibly due to nonsense-mediated decay and consistent with a well-identified mechanism for elimination of mRNA containing premature stop codons [27]. The npsnsmu5 and npsnsmu6 homozygotes were able to survive normally to adulthood, with further observation and breeding indicating that npsn-deficient zebrafish were morphologically indistinguishable from their heterozygous and WT siblings and capable of normal reproduction.

Figure 2.

Generation and identification of nps-deficient zebrafish. (a) The CRISPR/Cas9 system was used to generate npsn-knockout zebrafish. The Cas9 target was chosen as exon5 of npsn. Mutants were selected using T7E1 enzyme digestion and confirmed using Sanger sequencing. In F1 founders, a mutant line (−7, +0) containing a frameshift mutation was obtained and retained for follow-up studies. (b and c) Degradation of npsn mRNA in npsnsmu5 mutant embryos. (b) WISH results for npsn mRNA indicated significant decreases in npsnsmu5 mutant embryos at 3 dpf. (c) qRT-PCR results indicating that npsn mRNA expression was downregulated to 5% in npsnsmu5 mutant embryos. (Mean ± s.e.m., n = 20 per experiment, triplicated). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. ***p < 0.001.

2.3. npsn deficiency does not affect neutrophil number in zebrafish

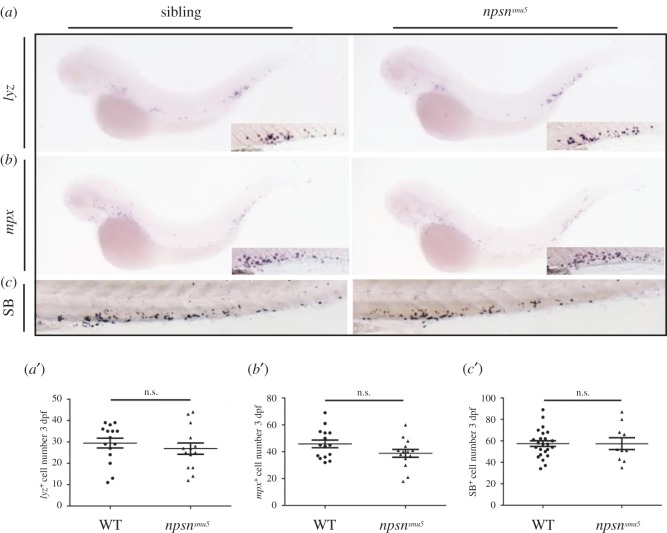

To determine whether loss of Npsn causes neutrophil defects, we examined the expression of neutrophil-specific genes. WISH results for mpx and lyz showed no difference in the expression of neutrophil markers between WT siblings and npsnsmu5 embryos (figure 3a,a′,b,b′). According to Sudan Black B staining, we also found no SB+ cell changes in the mutants (figure 3c,c′), suggesting unaltered neutrophil number in npsnsmu5 mutants. We then examined neutrophil granules by differential-interference contrast microscopy and found that granules were intact in npsnsmu5 embryos and WT siblings (data not shown), suggesting no visible developmental defects of neutrophils in npsnsmu5 mutants. These observations indicated that npsn deficiency did not cause developmental defects or affect neutrophil distribution.

Figure 3.

npsn deficiency does not affect neutrophil number in zebrafish. (a and a′) WISH analysis of lyz expression and quantification of lyz+ cells in the PBI at 3 dpf (29.5 ± 2.3 versus 26.9 ± 2.7) in WT sibling and npsnsmu5 mutant groups. (Mean ± s.e.m., n = 15 in each group, triplicated). Boxes in the lower right corner outline the magnified PBI regions. (b and b′) WISH analysis of mpx expression and quantification of mpx+ cells in the PBI at 3 dpf (45.9 ± 2.9 versus 38.9 ± 2.9) in WT sibling and npsnsmu5 mutant groups. (Mean ± s.e.m., n = 15 in each group, triplicated). Boxes in the lower right corner outline the magnified PBI regions. (c and c′) Sudan Black staining (SB) and quantification of SB+ cells in the PBI at 3 dpf (57.5 ± 2.7 versus 57.4 ± 5.4) in WT sibling and npsnsmu5 mutant groups). (Mean ± s.e.m., n ≥ 10 in each group, triplicated). Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test. n.s., not significant.

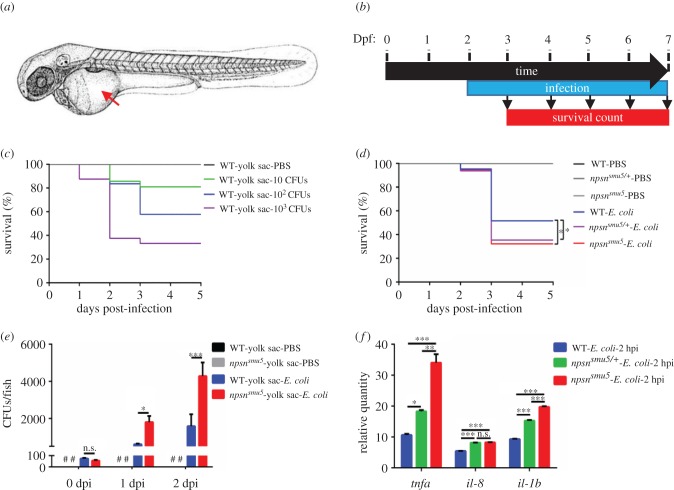

2.4. npsn deficiency affects host defence against E. coli infection

Neutrophils are indispensable for host defence against intruding microorganisms. To determine whether npsn deficiency affects zebrafish defence against bacterial infection, we infected WT and npsnsmu5 embryos in the yolk sac with E. coli as described previously [28] (figure 4a,b). First, the survival rate of infected embryos was determined to evaluate the appropriate infective dose, with results indicating that as few as 10 colony forming units (CFUs) of bacteria could be lethal to WT embryos in a dose-dependent manner (figure 4c), whereas 100 CFUs resulted in a survival rate of between approximately 40% and approximately 60%, resulting in its subsequent selection as a proper dosage for follow-up studies. We then detected whether npsn level was regulated by E. coli infection, and found that the expression of npsn was unaffected in neutrophils of bacteria-injected embryos compared with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-injected controls (electronic supplementary material, figure S3). All npsnsmu5 homozygous embryos, npsnsmu5/+ heterozygous embryos and WT embryos survived normally at 1 day post-infection (dpi), with death occurring at either 2 or 3 dpi. However, both the npsnsmu5 and npsnsmu5/+ embryos exhibited a significantly lower survival rate relative to their WT embryos at 3 dpi (figure 4d). These data indicated that npsn deficiency weakened host resistance to E. coli infection.

Figure 4.

npsn deficiency affects host defence against E. coli infection. (a) The infection site of the zebrafish yolk sac (the red arrow). (b) Scheme showing the experimental procedure used for survival assays. The npsnsmu5 mutants and WT controls were infected with E. coli at 2 dpf via the yolk sac, and the number of surviving larvae was counted daily over the next 5 days. At least three independent experiments were performed using greater than 60 embryos per group. (c) Survival curves of WT embryos challenged with different doses of E. coli. Mortality increased in a dose-dependent manner. (d) Survival curves of npsnsmu5 and WT embryos injected with 100 CFUs of E. coli (WT (n = 57); npsnsmu5 (n = 55) in total). Statistical significance was determined by the log-rank test. *p < 0.05. (e) Bacterial burden of embryos injected with E. coli. Significantly more bacterial cells were observed in npsnsmu5 mutant embryos when compared with those observed in WT controls at 1 and 2 dpi. Data were combined from three individual experiments (n = 50 per group), and statistical significance was determined using the two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons adjustment. *p < 0.05. ***p < 0.001. n.s., not significant. #, undetected. (f) Alteration of the inflammatory response in npsnsmu5 embryos at 2 hpi. The relative quantity of inflammatory factors il-1b, il-8 and tnfα was examined by qRT-PCR, and expression levels were adjusted for trauma (PBS-solution injection). (Mean ± s.e.m., n = 30 in each group, triplicated). Statistical significance was determined using the one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons adjustment. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. n.s., not significant.

We then measured kinetic curves associated with in vivo bacterial growth of infected embryos. Our results showed that by 2 dpi, E. coli proliferated in both WT and npsnsmu5 embryos, and that there was a significantly higher bacterial burden in npsnsmu5 mutant embryos at 1 and 2 dpi (figure 4e). These results revealed that E. coli proliferated faster in mutant embryos, implying that npsn deficiency affected host defence against E. coli infection. Collectively, these findings revealed that npsn deficiency impaired neutrophil-specific antibacterial response in zebrafish embryos.

To further investigate infection-induced alterations in inflammation, we detected the expression of inflammatory factors, such as tumour necrosis factor α (tnfα) [29], il-8 [30] and il-1b [31], during the early stage of infection, which could activate and induce neutrophil translocation to the infection site. Expression analysis by qRT-PCR at 2 hpi showed elevated expression of all genes to a more significant level in infected npsnsmu5 embryos and npsnsmu5/+ embryos than that in infected WT embryos and PBS-injected controls (figure 4f), suggesting a more severe inflammatory response in npsnsmu5 embryos. These findings clarified the changes in inflammatory response in npsnsmu5 mutants following E. coli infection.

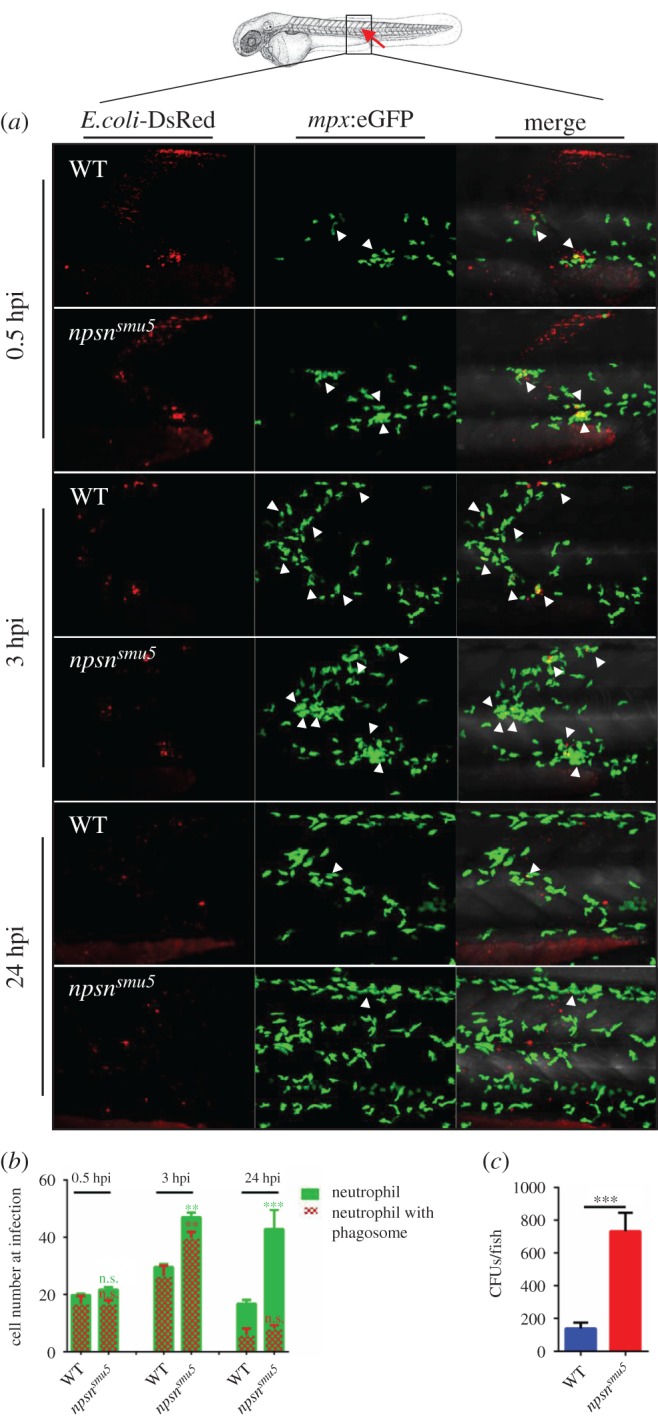

To further investigate whether neutrophil recruitment was affected in the npsnsmu5 embryos, we performed muscle infection in WT and npsnsmu5 embryos as previously described [22]. In WT embryos, 10–20 neutrophils first arrived at the infection site at 0.5 hpi, and the number increased to 25–35 at 3 hpi, which is consistent with previous observations [22]. As bacteria clearance completed, only 15–25 neutrophils were still at the infected site at 24 hpi (figure 5a,b). In the early stage of infection (0.5 hpi), npsnsmu5 embryos showed similar recruitment of neutrophils to WT embryos. However, recruited neutrophils in npsnsmu5 embryos were much more than in WT at 3 hpi, and were still accumulated without relief by 24 hpi (figure 5a,b). The number of neutrophils with phagosomes also increased in the npsnsmu5 embryos at 3 hpi (figure 5b). These results showed that npsnsmu5 embryos required more neutrophils to be recruited to form more phagosomes in clearance of bacteria, confirming that npsn-deficient embryos had severe inflammatory response. We further measured bacterial cells in infected embryos through muscle infection, and the results showed that there was a significantly higher bacterial burden in npsnsmu5 mutant embryos at 24 hpi (figure 5c), implying that npsn deficiency affected host defence against E. coli infection.

Figure 5.

npsn deficiency affects neutrophil recruitment to bacteria. (a) The infection site of the zebrafish muscle (the red arrow). DsRed+ E. coli were injected subcutaneously over one somite into WT and npsnsmu5 mutant embryos with Tg(mpx:eGFP) background, and images were captured at 0.5, 3 and 24 hpi. All images are maximum-intensity projection at an interval of 2 µm. The white triangle indicated the neutrophil with phagosomes. (b) Quantification of recruited mpx:eGFP+ neutrophil numbers (green bar) and phagocytosing neutrophil numbers (red net bar) in the infection site at each time point in bacterial injected WT and npsnsmu5 mutants. Average numbers with means in WT and npsnsmu5 mutant groups at 0.5, 3, 24 hpi (green bar: 19.7 ± 2.6 versus 21.7 ± 0.8; 28.6 ± 4.1 versus 47.0 ± 2.3; 17.5 ± 4.8 versus 42.8 ± 7.5); (red net bar: 16.9 ± 2.6 versus 16.83 ± 1.2; 26.4 ± 3.6 versus 39.8 ± 2.1; 5.9 ± 2.2 versus 8.2 ± 1.1). (Mean±s.e.m., n ≥ 6 in each group, triplicated). Statistical significance was determined using the two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons adjustment. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. n.s., not significant. (c) Bacterial burden of embryos at 24 hpi in npsnsmu5 mutant embryos and WT controls. (Mean±s.e.m., n = 50 in each group, triplicated). Statistical significance was determined using the unpaired t-test. ***p < 0.001.

2.5. npsn overexpression enhances host immune response against E. coli infection

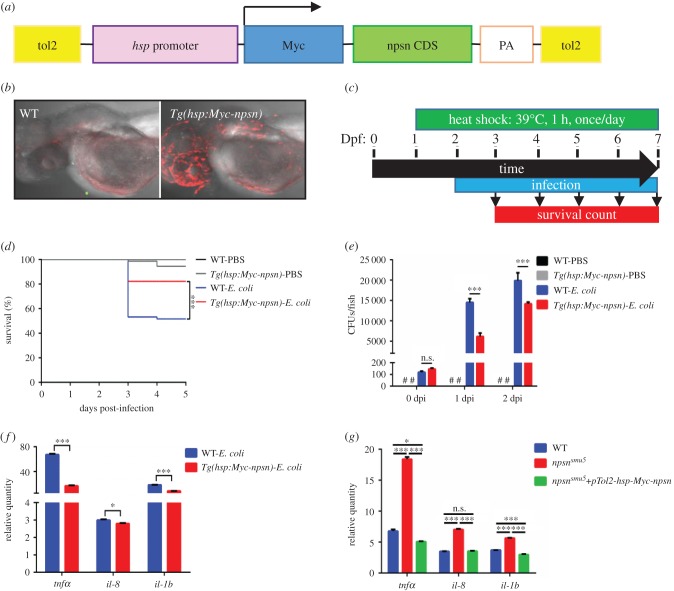

To assess whether Npsn enhances the clearance of E. coli, we cloned the Npsn-coding sequence fused with a 6×Myc tag and driven by the hsp promoter into the Tol2 vector (referred to as pTol2-hsp-Myc-npsn) (figure 6a). This construct was injected into one-cell-stage WT embryos, and the progenies of F0 founders were identified by anti-Myc staining. The F1 Myc+ embryos were selected and denoted as the Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) line (figure 6b). Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) and WT embryos were subsequently infected with E. coli and exposed to heat-shock conditions, followed by recording of survival rates (figure 6c). Our findings showed that the Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) line exhibited a significantly higher survival rate relative to the WT variants (figure 6d), suggesting that npsn overexpression enhanced host immune response to E. coli infection in zebrafish embryos.

Figure 6.

npsn overexpression enhances host response against E. coli infection. (a) Construction of the Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) transgenic plasmid. npsn-CDS (green bar) was inserted behind the hsp promoter and a Myc tag. (b) Anti-Myc staining of the Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) and WT embryos. (c) Scheme showing the experimental procedure used for the survival assays. Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) and WT embryos were heat shocked at 39°C for 1 h at 1 day prior to infection. Embryos were infected with E. coli at 2 dpf via the yolk sac and heated to 39°C for 1 h daily, and the number of surviving larvae was counted daily over the next 5 days. (d) Survival curves for Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) and WT embryos following injection with 100 CFUs of E. coli (WT (n = 60); Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) (n = 60)). Statistical significance was determined using the log-rank test. ***p < 0.001. (e) Bacterial burden of embryos injected with E. coli. Less bacterial cells in Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) at 1 and 2 dpi than in WT. Data were combined from three individual experiments (n = 50 per group), and statistical significance was determined using the two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons adjustment. ***p < 0.001. n.s., not significant. #, undetected. (f) Alteration of the inflammatory response in Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) embryos at 2 hpi. The relative quantity of tnfα, il-8 and il-1b was examined by qRT-PCR, and expression levels were adjusted for trauma (PBS-solution injection). (Mean±s.e.m., n = 30 in each group, triplicated). Statistical significance was determined using the two-tailed Student's t-test. *p < 0.05. ***p < 0.001. (g) The altered expression of inflammatory cytokines could be rescued by npsn overexpression. The relative quantity of tnfα, il-8 and il-1b was examined by qRT-PCR, and expression levels were adjusted for trauma (PBS-solution injection). (Mean±s.e.m., n = 30 in each group, triplicated). Statistical significance was determined using the one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons adjustment. *p < 0.05. ***p < 0.001. n.s., not significant.

When we measured kinetic curves associated with in vivo bacterial growth of infected embryos, we found that the bacterial burden in Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) embryos was significantly lower than in WT embryos at 1 and 2 dpi (figure 6e). The data revealed that E. coli proliferated more slowly in the npsn overexpression embryos, indicating that npsn overexpression could enhance host defence against E. coli infection in zebrafish embryos. The expression of inflammatory factors (tnfα, il-8 and il-1b) was lower in Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) embryos than in WT controls (figure 6f), suggesting the reduced inflammation in npsn overexpression embryos. Moreover, overexpressing npsn could rescue the altered inflammatory response in npsnsmu5 mutant embryos (figure 6g), indicating the importance of Npsn in host defence against bacteria.

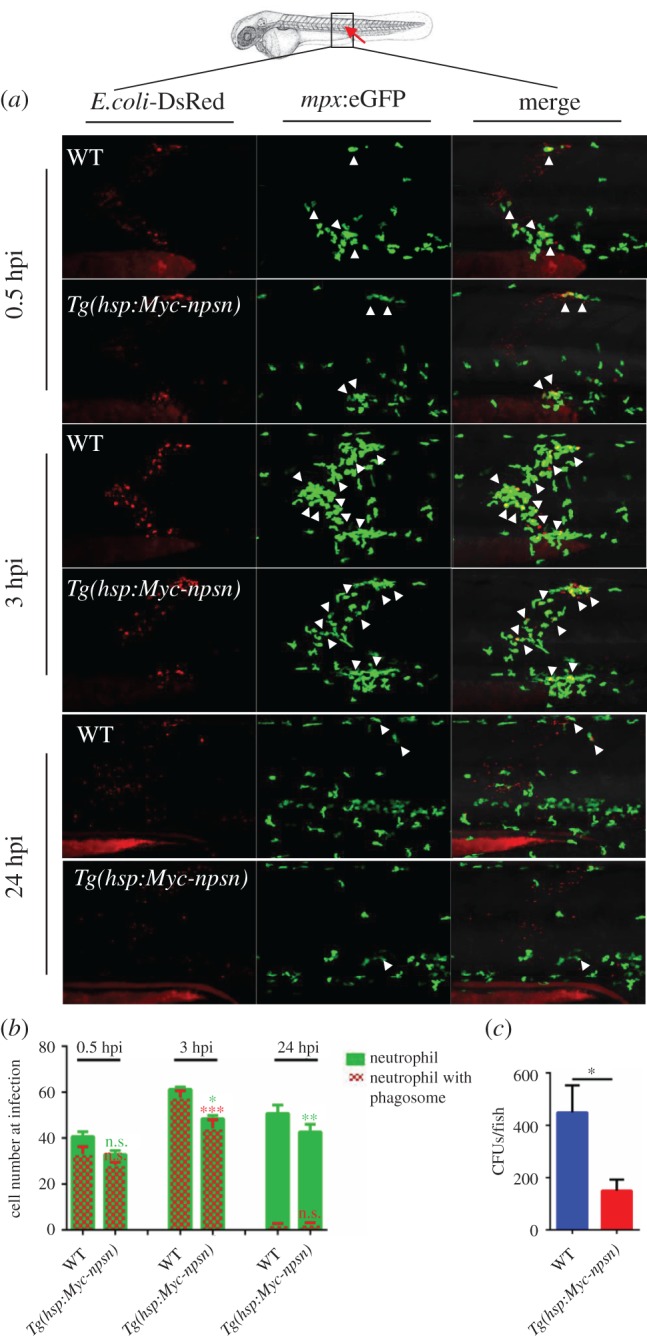

In muscle infection assay, neutrophil recruitment was observed and numbers were calculated at 0.5, 3 and 24 hpi. Compared with WT control embryos, Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) embryos had decreased number of recruited neutrophils, as well as decreased phagocytosing neutrophils in the infected site (figure 7a,b). These results indicated that npsn overexpression embryos required less neutrophils to be recruited in clearance of bacteria, supporting that npsn overexpression embryos had reduced inflammation during infection and enhanced host immune response to E. coli infection. Consistently, bacterial burden in Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) embryos was significantly lower than in WT embryos at 24 hpi (figure 7c), which further indicates npsn overexpression improved neutrophil-specific antibacterial response in zebrafish embryos.

Figure 7.

Less neutrophils are recruited at the infection in Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) embryos. (a) The infection site of the zebrafish muscle (the red arrow). DsRed+ E. coli were injected subcutaneously over one somite into WT and Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) embryos with Tg(mpx:eGFP) background, and images were captured at 0.5, 3 and 24 hpi. All images are maximum-intensity projection at an interval of 2 μm. White triangles indicated neutrophils with phagosomes. (b) Quantification of recruited mpx:eGFP+ neutrophil numbers (green bar) and phagocytosing neutrophil numbers (red net bar) in the infection site at each time point in bacterial injected WT and Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) embryos. Average numbers with means in WT and Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) groups at 0.5, 3, 24 hpi (green bar: 41.0 ± 2.0 versus 32.8 ± 1.5; 61.2 ± 3.1 versus 48.4 ± 3.0; 47.8 ± 4.5 versus 33.0 ± 3.7); (red net bar: 33.0 ± 3.3 versus 28.2 ± 81.3; 57.6 ± 3.0 versus 44.3 ± 3.7; 2.2 ± 0.6 versus 2.4 ± 0.7). (Mean±s.e.m., n ≥ 6 in each group, triplicated). Statistical significance was determined using the two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons adjustment. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. n.s., not significant. (c) Bacterial burden of embryos at 24 hpi in Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) embryos and WT controls. (Mean±s.e.m., n = 50 in each group, triplicated). Statistical significance was determined using the unpaired t-test. *p < 0.05.

3. Discussion

In this study, we generated an npsn-deficient zebrafish mutant and established the Tg(npsn:EGFP)smu7 transgenic line, which provided a useful tool for studying neutrophil development and behaviour during host wound healing or defence against infection in vivo. The CRISPR/Cas9-generated npsn-deficient mutants exhibited unaltered neutrophil number and no obvious developmental defects in their neutrophils. When challenged with E. coli, npsnsmu5 embryos exhibited a lower survival rate and higher bacterial burden, as well as an augmented inflammatory response, relative to WT variants. Additionally, npsn-overexpressing zebrafish exhibited higher survival rates, reduced bacterial burden, as well as reduced inflammatory response, when compared with WT variants, indicating that zebrafish Npsn promoted host immune defence against bacterial infection.

Given that Npsn is a component of neutrophil granzymes, npsn deficiency affected neutrophil function rather than overall neutrophil development and concentration. E. coli is a Gram-negative and non-pathogenic bacterium; however, infection of the zebrafish yolk sac with E. coli [28] was lethal at doses as low as 10 CFUs. Additionally, infection of npsnsmu5 mutants and their WT controls revealed that npsnsmu5 mutants exhibited a lower survival rate and higher bacterial burden when compared with WT, suggesting that npsn deficiency impaired host defence against E. coli infection. Furthermore, during the early stage of infection, the expression of inflammatory factors (il-1b [31], il-8 [30] and tnfα [29]) increased significantly in the npsnsmu5 embryos. Elevated levels of cytokine transcription might be explained by functional defects associated with neutrophils, resulting in their inability to engulf and degrade invading microbes, thereby leading to greater bacterial burden in the mutant embryos.

Although we confirmed that npsn deficiency impaired host defence against bacterial infection, the mechanisms associated with this deficiency are unclear. Npsn is a zinc metalloendopeptidase, and a previous in vitro study showed that Npsn hydrolyzes gelatin and fibronectin, which are important components of the extracellular matrix [12,32]. Besides bony fish, Npsn homologues could be found in Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster as well as in parasites [33], while no direct mammalian homologues were found (data not shown). By BLAST comparison with the human and mice protein databases, zebrafish Npsn shared about 40% similarity with human and mouse astacin-like metalloendopeptidase, meprin proteinases, bone morphogenetic protein 1 (Bmp1) and tolloid-like protein 1/2, owing to a conserved astacin domain (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). These hit proteins exhibited diverse biological functions, including matrix assembly, digestion and signalling pathway activation in developmental morphogenesis and tissue differentiation [34–36]. Here, we found zebrafish Npsn also plays important roles in innate immunity. We found that npsn-deficient neutrophils had not lost the ability to engulf the microbe, as neutrophils with phagosomes were observed. And the myeloperoxidase activity was also normal in npsn-deficient neutrophils (data not shown). However, embryos with npsn deficiency had impaired host defence against bacterial infection, with more neutrophils recruited to the infected site and increased host inflammatory response. Thus it is likely that Npsn may function as a hydrolase to conduct neutrophils for the degradation of engulfed microbes by hydrolysis, or may function as its mammalian counterparts (e.g. Bmps etc.) to play roles as a signal molecule for inflammatory response, which needs further investigation.

In conclusion, this study confirmed that zebrafish Npsn is important to the host immune response against bacterial infection. Our results suggested that npsn-deficient and -overexpressing zebrafish could serve as valuable models for in vivo investigation of host innate immune response to bacterial pathogens.

4. Material and methods

4.1. Zebrafish lines and maintenance

All zebrafish lines were raised and maintained under standard conditions [37]. The lines Tg(mpx:EGFP) [38], Tg(mpeg1:EGFP) [39] and Tg(lyz:DsRed) [40] were previously described. Zebrafish embryos were maintained in ‘egg water’ containing 0.002% methylene blue to prevent fungal growth, which was replaced with fresh egg water containing 0.003% N-phenylthiourea (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) at 10 hpf to 24 hpf to prevent pigmentation.

4.2. npsn-knockout by CRISPR/Cas9

npsn-deletion transcripts were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 technology targeting the fifth exon of the npsn gene. The Cas9-targeting sequence was as follows: 5′-GGAGACAT CGCCTTTCCCAG-3′. Cas9 mRNA and genomic RNA were synthesized using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE mRNA transcription-synthesis kit (AM1344; Ambion; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using PCR products with the following primer combinations: forward, 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGAGACATCGCCTTTCCCAGGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC-3′; and reverse, 5′-AGCACCGACTCGGTGCCACT-3′ [41]. Cas9 mRNA (300 ng µl−1) and gRNA (guide RNA, 100 ng µl−1) were co-injected into one-cell-stage WT embryos. To determine mutation efficiency, genomic DNA was extracted from 24 embryos (three embryos per group), followed by T7 endonuclease I digestion (M0302S; NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) and Sanger sequencing. The target region was amplified using a forward primer 5′-GGACAGTGCTATTGCGTTTGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCCTTGTTCAATCACTGCTACTTC-3′. The remainder of the embryos were raised to sexual maturity, and positive F0 adults were mated with WT to obtain the F1 generation. Positive F1 adults were detected as the F0 generation, and positive F1 zebrafish with identical mutations were intercrossed to obtain F2 homozygous-mutant and WT offspring. In this programme, npsnsmu5 mutants were used for experiments and WT siblings as controls. The npsn exon6-Cas9 was designed and synthesized according to a similar protocol to obtain a mutant (−0, +1) (npsnsmu6) harbouring a frameshift mutation.

4.3. In vitro synthesis of antisense RNA probes and WISH

The antisense RNA probes for mpx, lyz and npsn were prepared by in vitro transcription according to a standard protocol [42]. WISH was performed at a hybridization temperature of 65°C as described previously [43].

4.4. RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of 2 μg RNA was used in a RT reaction using Moloney murine leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (M1701; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and oligo-dT (18) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting cDNA was diluted three times for use in qRT-PCR assays. Each 10 μl reaction mixture contained 1 µl cDNA, 200 nM of each gene-specific primer (electronic supplementary material, table S1), and 5 µl of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed on a LightCycler 96 system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and quantitation was performed in triplicate wells. All reactions were normalized against β-actin, and melting-curve analysis confirmed the presence of only one PCR product. Significance was determined by using a Student's t-test with a significance threshold of p < 0.05.

4.5. Double fluorescence immunohistochemistry staining

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously [44]. To examine the co-staining of GFP or DsRed with npsn WISH, embryos were first incubated with an npsn antisense probe as described previously, except that the signal was expanded using a TSA Plus fluorescein evaluation kit (NEL741E001KT; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) or TSA Plus cyanine 3 evaluation kit (NEL744E001KT; PerkinElmer). For antibody staining, embryos were first stained with goat anti-GFP or rabbit anti-DsRed antibody (1 : 200) at 4°C overnight and subsequently visualized by Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat (1 : 400) at 4°C overnight or Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-rabbit (1 : 400) 4°C overnight, respectively.

4.6. Bacterial infection

The DsRed-labelled XL10 E. coli cells [33] were expanded at 37°C in a shaker until reaching an optical density of between 1 and 1.5. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 5000g for 5 min and resuspended in sterile PBS. The working concentration of E. coli was 2 × 108 ml−1, and an approximately 0.5 nl bacterial suspension was injected into 2 dpf embryos with 0.02% tricaine. E. coli cells (100 CFU) were injected into the yolk sac with a gas manipulator (Havard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) for survival-rate counts. Muscle infection was performed as described previously [22]; E. coli cells (103 CFU) were injected subcutaneously over a somite in 2 dpf embryos.

To get a comparable genetic background between the controls and npsnsmu5 mutants, the off-spring (F1) from npsnsmu5/+ heterozygote (F0) inter-crossing were raised and genotyped for WT pool and mutant pool; the intercrossed off-spring (F2) from each pool were utilized for the infection as WT controls and npsnsmu5 mutants, respectively.

4.7. Establishment of stable transgenic lines

To establish the Tg(npsn:EGFP)smu7 line, we cloned the npsn regulatory sequence containing putative npsn promoter elements by PCR using npsn-specific primers (forward, 5′-CCGCTCGAGCAAGCCAAGCAAGAGTTTTACAAG-3′; reverse, 5′-CCCAAGCTTACCATCAATCAGCCATAATTCAGC-3′). The 2-kb DNA sequence upstream of the npsn translation start site was identified, placed upstream of GFP, and subcloned into the pTol vector with minimal Tol2 elements and an SV40 polyA sequence to form the pTol2-npsn-EGFP construct. To generate the transgenic line, 75 pg of the pTol2-npsn-EGFP construct and 25 pg of transposase mRNA were co-injected into zebrafish embryos at the one-cell stage. Founders were selected by fluorescence microscopy and identified by PCR of the transgenic line. Stable F1 Tg(npsn:EGFP)smu7 embryos were obtained by mating founder fish with AB fish and confirmed by anti-GFP immunostaining. The transgenic line Tg(hsp:Myc-npsn) was founded using a similar protocol.

4.8. Statistical methods

Calculated data were recorded and analysed using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Student's t-test was used for comparisons between two groups, and one-way or two-way analysis of variance was used for comparisons among multiple groups, whereas comparison of survival curves was performed using the log-rank test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Li Li for sharing with us the DsRed-E. coli strain.

Ethics

Experimental procedures and protocols to maintain zebrafish lines were performed according to the institutional license guidelines.

Data accessibility

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

Y.Z. initiated the research. Q.D. designed the research, performed most of the experiments and analysed the data. Q.L., Z.H. and Y.C. performed some of the experiments. Q.D. and Y.Z. designed the research, analysed the data and prepared the manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31471378 and 31701295) and the Team Program of Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2014A030312002).

References

- 1.Witko-Sarsat V, Rieu P, Descamps-Latscha B, Lesavre P, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. 2000. Neutrophils: molecules, functions and pathophysiological aspects. Lab. Invest. 80, 617–653. (doi:10.1038/labinvest.3780067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amulic B, Cazalet C, Hayes GL, Metzler KD, Zychlinsky A. 2012. Neutrophil function: from mechanisms to disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30, 459–489. (doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074942) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dinarello CA. 1996. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood 87, 2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wawrocki S, Druszczynska M, Kowalewicz-Kulbat M, Rudnicka W. 2016. Interleukin 18 (IL-18) as a target for immune intervention. Acta Biochim. Pol. 63, 59–63. (doi:10.18388/abp.2015_1153) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephan A, Batinica M, Steiger J, Hartmann P, Zaucke F, Bloch W, Fabri M. 2016. LL37:DNA complexes provide antimicrobial activity against intracellular bacteria in human macrophages. Immunology 148, 420–432. (doi:10.1111/imm.12620) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy O. 2004. Antimicrobial proteins and peptides: anti-infective molecules of mammalian leukocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 76, 909–925. (doi:10.1189/jlb.0604320) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faurschou M, Borregaard N. 2003. Neutrophil granules and secretory vesicles in inflammation. Microbes Infect. 5, 1317–1327. (doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2003.09.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinauer MC, Lekstrom-Himes JA, Dale DC. 2000. Inherited neutrophil disorders: molecular basis and new therapies. Hemat. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2000, 303–318. (doi:10.1182/asheducation-2000.1.303) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K, et al. 2015. Myeloperoxidase-deficient zebrafish show an augmented inflammatory response to challenge with Candida albicans. Fish Shellfish Immun. 44, 109–116. (doi:10.1016/j.fsi.2015.01.038) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shafer WM, Katzif S, Bowers S, Fallon M, Hubalek M, Reed MS, Veprek P, Pohl J. 2002. Tailoring an antibacterial peptide of human lysosomal cathepsin G to enhance its broad-spectrum action against antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens. Curr. Pharm. Des. 8, 695–702. (doi:10.2174/1381612023395376) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spitznagel JK, Shafer WM. 1985. Neutrophil killing of bacteria by oxygen-independent mechanisms: a historical summary. Rev. Infect. Dis. 7, 398–403. (doi:10.1093/clinids/7.3.398) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung CH, Huang HR, Huang CJ, Huang FL, Chang GD. 1997. Purification and cloning of carp nephrosin, a secreted zinc endopeptidase of the astacin family. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13 772–13 778. (doi:10.1074/jbc.272.21.13772) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterchi EE, Stocker W, Bond JS. 2008. Meprins, membrane-bound and secreted astacin metalloproteinases. Mol. Aspects Med. 29, 309–328. (doi:10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song HD. et al 2004. Hematopoietic gene expression profile in zebrafish kidney marrow. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 16 240–16 245. (doi:10.1073/pnas.0407241101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbomel P, Thisse B, Thisse C. 1999. Ontogeny and behaviour of early macrophages in the zebrafish embryo. Development 126, 3735–3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieschke GJ, Oates AC, Crowhurst MO, Ward AC, Layton JE. 2001. Morphologic and functional characterization of granulocytes and macrophages in embryonic and adult zebrafish. Blood 98, 3087–3096. (doi:10.1182/blood.V98.10.3087) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Guyader D, et al. 2008. Origins and unconventional behavior of neutrophils in developing zebrafish. Blood 111, 132–141. (doi:10.1182/blood-2007-06-095398) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seeger A, Mayer WE, Klein J. 1996. A complement factor B-like cDNA clone from the zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio). Mol. Immunol. 33, 511–520. (doi:10.1016/0161-5890(96)00002-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lieschke GJ, Trede NS. 2009. Fish immunology. Curr. Biol. 19, R678–R682. (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.068) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mostowy S, et al. 2013. The zebrafish as a new model for the in vivo study of Shigella flexneri interaction with phagocytes and bacterial autophagy. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003588 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003588) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tobin DM, et al. et al 2010. The lta4h locus modulates susceptibility to mycobacterial infection in zebrafish and humans. Cell 140, 717–730. (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colucci-Guyon E, Tinevez JY, Renshaw SA, Herbomel P. 2011. Strategies of professional phagocytes in vivo: unlike macrophages, neutrophils engulf only surface-associated microbes. J. Cell Sci. 124, 3053–3059. (doi:10.1242/jcs.082792) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen-Chi M, Phan QT, Gonzalez C, Dubremetz JF, Levraud JP, Lutfalla G. 2014. Transient infection of the zebrafish notochord with E. coli induces chronic inflammation. Dis. Model Mech. 7, 871–882. (doi:10.1242/dmm.014498) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borregaard N. 2010. Neutrophils, from marrow to microbes. Immunity 33, 657–670. (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin H, et al. 2016. c-Myb acts in parallel and cooperatively with Cebp1 to regulate neutrophil maturation in zebrafish. Blood 128, 415–426. (doi:10.1182/blood-2015-12-686147) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tobin DM, May RC, Wheeler RT. 2012. Zebrafish: a see-through host and a fluorescent toolbox to probe host–pathogen interaction. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002349 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002349) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brogna S, Wen J. 2009. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) mechanisms. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 107–113. (doi:10.1038/nsmb.1550) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyrkalska SD, et al. 2016. Neutrophils mediate Salmonella typhimurium clearance through the GBP4 inflammasome-dependent production of prostaglandins. Nat. Commun. 7, 12077 (doi:10.1038/ncomms12077) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novoa B, Figueras A. 2012. Zebrafish: model for the study of inflammation and the innate immune response to infectious diseases. Curr. Top. Innate Immunity II 946, 253–275. (doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0106-3_15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Oliveira S, Reyes-Aldasoro CC, Candel S, Renshaw SA, Mulero V, Calado A. 2013. Cxcl8 (IL-8) mediates neutrophil recruitment and behavior in the zebrafish inflammatory response. J. Immunol. 190, 4349–4359. (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1203266) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dinarello CA. 2011. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood 117, 3720–3732. (doi:10.1182/blood-2010-07-273417) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai PL, Chen CH, Huang CJ, Chou CM, Chang GD. 2004. Purification and cloning of an endogenous protein inhibitor of carp nephrosin, an astacin metalloproteinase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 11 146–11 155. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M310423200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Sar AM, Musters RJP, van Eeden FJM, Appelmelk BJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CMJ. E, Bitter W. 2003. Zebrafish embryos as a model host for the real time analysis of Salmonella typhimurium infections. Cell. Microbiol. 5, 601–611. (doi:10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00303.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimell MJ, Ferguson EL, Childs SR, O'Connor MB. 1991. The Drosophila dorsal-ventral patterning gene tolloid is related to human bone morphogenetic protein 1. Cell 67, 469–481. (doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90522-Z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ge G, Greenspan DS. 2006. Developmental roles of the BMP1/TLD metalloproteinases. Birth Defects Res Part C Embryo Today 78, 47–68. (doi:10.1002/bdrc.20060) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norman LP, Jiang W, Han X, Saunders TL, Bond JS. 2003. Targeted disruption of the meprin β gene in mice leads to underrepresentation of knockout mice and changes in renal gene expression profiles. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 1221–1230. (doi:10.1128/MCB.23.4.1221-1230.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Westerfield M. 1993. The zebrafish book: a guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio). Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Renshaw SA, Loynes CA, Trushell DM, Elworthy S, Ingham PW, Whyte MK. 2006. A transgenic zebrafish model of neutrophilic inflammation. Blood 108, 3976–3978. (doi:10.1182/blood-2006-05-024075) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellett F, Pase L, Hayman JW, Andrianopoulos A, Lieschke GJ. 2011. mpeg1 promoter transgenes direct macrophage-lineage expression in zebrafish. Blood 117, E49–E56. (doi:10.1182/blood-2010-10-314120) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall C, Flores MV, Storm T, Crosier K, Crosier P. 2007. The zebrafish lysozyme C promoter drives myeloid-specific expression in transgenic fish. BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 42 (doi:10.1186/1471-213X-7-42) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang N, Sun C, Gao L, Zhu D, Xu X, Zhu X, Xiong JW, Xi JJ. 2013. Genome editing with RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease in zebrafish embryos. Cell Res 23, 465–472. (doi:10.1038/cr.2013.45) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chitramuthu BP, Bennett HPJ. 2013. High resolution whole mount in situ hybridization within zebrafish embryos to study gene expression and function. J Vis Exp. 80, 50644 (doi:10.3791/50644) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westerfield M, Doerry E, Kirkpatrick AE, Douglas SA. 1999. Zebrafish informatics and the ZFIN database. Methods Cell Biol. 60, 339–355. (doi:10.1016/S0091-679X(08)61909-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin H, Xu J, Qian F, Du L, Tan CY, Lin Z, Peng J, Wen Z. 2006. The 5′ zebrafish scl promoter targets transcription to the brain, spinal cord, and hematopoietic and endothelial progenitors. Dev. Dyn. 235, 60–67. (doi:10.1002/dvdy.20613) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.