Abstract

Objective

Left ventricular remodelling following a ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) is an adaptive response to maintain the cardiac output despite myocardial tissue loss. Limited studies have evaluated long term ventricular function using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) after STEMI.

Methods

Study population consisted of 155 primary percutaneous coronary intervention treated first STEMI patients. CMR was performed at 4±2 days, 4 months and 24 months follow-up. Patients were treated with beta-blockers, ACE-inhibitors or AT-II- inhibitors, statins and dual antiplatelet according to current international guidelines.

Results

Mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at baseline was 44%±8%. Twenty-one per cent of the study population had an increase of more than 5.0% after 4 months of follow-up and 21% of the cohort had a decrease of more than 5.0%. Patients with long-term LVEF deterioration have significantly larger end-systolic volumes than patients with improvement of LVEF (61±23 mL/m2 compared with 52±21 mL/m2, p=0.02) and less wall thickening in the remote zone. Patients with LVEF improvement had significantly greater improvement in wall thickening in the infarct areas and in the non-infarct or remote zone.

Conclusion

Contrary to previous studies, we demonstrate that myocardial remodelling after STEMI is a long-term process. Long-term LVEF deterioration is characterised by an increase in end-systolic volume and less wall thickening in the remote zones. Patients with LVEF improvement exhibit an increase in left ventricular wall thickening both in the infarct as well as in the remote zones.

Trial registration

The HEBE study is registered in The Netherlands Trial Register #NTR166 (www.trialregister.nl) and the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial, #ISRCTN95796863 (https://c-d-qn9pqajji.sec.amc.nl).

Keywords: cardiac remodelling, MRI, STEMI

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Adverse left ventricular (LV) remodelling after revascularisation for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a major determinant for the short-term and long-term clinical outcomes. When remodelling occurs, the entire heart can be involved, as disproportionate thinning and dilation in the infarct region (ie, infarct expansion) is accompanied by a distortion in shape of the entire heart with volume-overload hypertrophy of the non-infarcted myocardium.

What does this study add?

The results of the current study show that LV remodelling, both positive and negative, is an ongoing process and continues at least up to 2 years after STEMI, involving the infarct zone and remote zones. Long-term left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) deterioration is characterised by an increase in end-systolic volume and less wall thickening in the remote zones. Patients with long-term LVEF improvement exhibit an increase in left ventricular wall thickening both in the transmural infarct and remote zones.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

This study points out that monitoring and treatment of adverse LV remodelling after acute myocardial infarction should be performed up to at least 2 years of follow-up. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the defined cut of value for myocardium viability (75% transmurality as assessed by CMR) is questionable as the infarct zone exhibits improvement at long-term follow-up. To conclude, despite the fact that early remodelling may initially seem adaptive with early maintenance of cardiac output, this continuous remodelling process may only further deteriorate the LV with increased LV volumes and increased incidence of heart failure and cardiovascular death.

Introduction

Left ventricular remodelling after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention is a major determinant for the short-term and long-term clinical outcomes.1 Adverse left ventricular remodelling refers to alterations in ventricular architecture involving both the infarcted and non-infarcted zones leading to progressive increase in systolic and diastolic left ventricular volumes.2–4 Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) has emerged as the gold standard for assessing the functional and morphological changes of the left ventricle.4 To date, there is limited CMR data assessing long-term left ventricular function and the long-term LV remodelling process after STEMI. Especially, there is limited data regarding LV function changes after the initial months. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the early (baseline–4 months) and late remodelling process (4–24 months) assessed by CMR. Moreover, segmental CMR analysis was used to provide more insight in the LV remodelling process.

Methods

Study population

The study population consisted of patients with STEMI included in the HEBE study, which is a multicentre, randomised trial assessing intracoronary bone marrow cell therapy (#ISRCTN95796863 and #NTR166). This study is a CMR subanalysis of this trial. The details of the design and results have been published previously.5 CMR imaging was performed at baseline, 4 months and 2 years of follow-up. In summary, patients 30–75 years of age were eligible for inclusion if they met the following inclusion criteria: successful percutaneous coronary intervention within 12 hours after onset of symptoms, three or more hypokinetic or akinetic left ventricular (LV) segments observed on echocardiography performed at least 12 hours after percutaneous coronary intervention, and an elevation of creatine kinase (CK) or creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB)more than 10 times the local upper limit of normal (ULN). Patients with a previous myocardial infarction were not included in this study. There were no significant differences between the two treatment groups and the control group at baseline.5 All patients were treated with primary PCI (PPCI) with stent implantation within 12 hours of symptom onset. Patients were treated with aspirin, heparin and a P2Y12 inhibitor according to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association practice guidelines.

Of the 200 patients that originally enrolled in the HEBE study, at 24 months, one had withdrawn informed consent, three had died, three did not consent to this additional long-term follow-up and three were lost to follow-up. At 24 months, 19 patients had clinical follow-up but did not undergo CMR because of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation (n=8), pacemaker implantation (n=1) or because they refused (n=10). Additionally, 12 patients were excluded from core lab analysis due to one of the following reasons: poor quality due to breathing or triggering artefacts, or baseline, 4 months and 24 months could not be matched. Of the remaining 159 patients, four patients had a recurrent myocardial infarction in the 2 years of follow-up and were also excluded from the analysis.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Patients were studied on the same clinical magnetic resonance scanner system for the consecutive studies (Siemens 1.5T, Erlangen, Germany; Philips 1.5T and 3.0T, Best, the Netherlands; GE Healthcare1.5T, Buckinghamshire, UK). The CMR protocol at 24 months was similar to the CMR protocol at baseline and 4 months, with the exception that no contrast medium was administrated to assess size and extent of infarction. At baseline and at 4 months' delayed enhancement (DE) was done 10–15 min after administration of a gadolinium-based contrast agent (Dotarem, Guerbet, Roissy, France; 0.2 mmol/kg) with a two-dimensional segmented inversion recovery gradient-echo pulse sequences. Typical in-plane resolution was 1.4×1.7 mm2, with a slice thickness of 5.0–6.0 mm (repetition time/echo time=9.6/4.4/4.4 ms, flip angle 25°, triggering to every other heartbeat). Inversion time was set to null the signal of viable myocardium.

Moreover, contiguous short axis slices were acquired every 10 mm covering the whole left ventricle using a cine retrospectively ECG-gated segmented steady-state free precession pulse sequence, with image parameters identical to the baseline and 4 months follow-up scan. Left ventricle (LV) volumes and mass were measured on the cine images and indexed for body-surface area. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated following assessment of left ventricle end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) and left ventricle end-systolic volume (LVESV).

For analysis of regional myocardial function, each short axis slice was divided in 12 equiangular segments to calculate wall thickening (in mm) of each segment by subtracting end-diastolic from end-systolic wall thickness. Segmental wall thickness was measured at end-systole and end-diastole after manual tracing of endocardial and epicardial borders in stop-frame images, excluding trabeculations and papillary muscles. The contours were drawn blinded to patient identity, clinical history and scan time point. Segmental wall thickness was calculated as the average of the chords within one segment. Segmental wall thickening (SWT) in millimetres was calculated as: end-systolic wall thickness minus end-diastolic wall thickness.

All CMR analyses were performed in a core laboratory by two experienced technicians using a standardised protocol, and analyses were supervised by a third reader with >10 years of CMR experience. They were all blinded to treatment allocation. Both baseline and 4-month follow-up scan were used to match all three CMR imaging for slice position using anatomic landmarks, such as papillary muscles and right ventricular insertion sites to have consistent comparison between the acquisitions. The CMR data were analysed using a dedicated software package (Mass, Medis, Leiden, The Netherlands).

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as frequencies (percentage) and continuous data as mean±SD. The study population was divided in a group with LVEF improvement and LVEF deterioration. LVEF improvement was defined as any increase of LVEF between baseline and 4 months and 4 months and 24 months. LVEF deterioration was defined as no improvement of LVEF, or a decrease in LVEF between two sequential CMR imaging time points. Unpaired Student’s t-test and a Fisher’s exact test were used to compare differences between groups of continuous and categorical variables, respectively. To account for non-independence of the data, we used multilevel logistic regression to analyse the relation between wall thickening and improvement of LVEF. In the multivariate analysis, treatment as randomised in the HEBE trial was always entered as a covariate. We used two levels (segments clustered within patients). All p values are two sided, and statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Statistical analysis was done with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS V.21.0 for Windows).

Results

The final study population consisted of 155 patients, with an average age of 56 years. The majority of the study population was male, namely 85%. Also, more than half of the patients had an anterior infarction (63%). Mean LVEF at baseline was 44%±8%, at 4 months 48%±9% and at 2 year follow-up 48%±9%. Infarct size at baseline was 22±12 g. Microvascular obstruction was present in 58% of the patients (table 1). There was a systematic use of secondary prevention treatment with beta-blockers and ACE-inhibitors. At discharge, 95% of the study population received ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor antagonist and 94% beta-blockers (table 1). During the initial 4 months we observed a mean LVEF increase of 4±7%.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for study population

| n=155 | |

| Age (years) | 56±9 |

| Male gender | 132 (85%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (6%) |

| Known hypertension | 47 (30%) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 29 (19%) |

| Current cigarette smoking | 79 (51%) |

| Time from symptom onset to PCI (hours)* | 3.3 (2.2–4.5) |

| Anterior infarction | 98 (63%) |

| Medication at discharge | |

| ACE-inhibitors/ATII antagonists | 147 (95%) |

| Beta-blockers | 146 (94%) |

| Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging | |

| LVEF (%) | 44±8 |

| End-diastolic volume (mL/m2) | 98±16 |

| End-systolic volume (mL/m2) | 56±14 |

| Infarct size (g)† | 22±12 |

| Presence of microvascular obstruction | 90 (58%) |

*Median (25th–75th percentile).

†Analysis available in 132 patients.

AT, angiotensin; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Late remodelling (4–24 months)

Between 4 months and 24 months of follow-up there was no LVEF change for the entire population (0%±7%). Twenty-one per cent of the study population had an increase of more than 5.0% after 4 months of follow-up and 21% of the cohort had a decrease of more than 5.0%. Table 2 displays the CMR parameters split for patients with LVEF improvement (n=78) versus patients with LVEF deterioration (n=77) between 4 and 24 months of follow-up. Patients with LVEF deterioration had a significantly larger LVESV at 24 months compared with the group with LVEF improvement (61±23 mL/m2 compared with 52±21 mL/m2, p=0.02), without differences in LVEDV. No difference in baseline infarct size was observed in patients who had LVEF improvement versus patients with LVEF deterioration (21±13 vs 22±12, p=0.62). There was also no difference in microvascular obstruction (54% vs 63%, p=0.33). There was no difference in medication use at 4 months (table 2). However, patients with LVEF deterioration more frequently did not use beta-blockers at 24 months (20% vs 4%, p=0.004) (table 3). When comparing the clinical outcomes in the 5-year follow-up of the two patient groups, there were no significant differences in New York Heart Association classification, occurrence of heart failure, repeat PCI, recurrent myocardial infarction and mortality.

Table 2.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging parameters for study population split for change in left ventricular ejection fraction between 4 months and 24 months

| LVEF improvement (n=78) |

LVEF deterioration (n=77) |

p Value | |

| LVEF (%) | |||

| At 3–5 days | 45±9 | 43±8 | 0.07 |

| 4 months | 46±8 | 50±9 | 0.007 |

| 24 months | 51±9 | 44±8 | 0.001 |

| LVEDV (mL/m2) | |||

| 3–5 days | 98±16 | 98±15 | 0.85 |

| 4 months | 104±22 | 104±22 | 0.96 |

| 24 months | 104±26 | 107±25 | 0.47 |

| LVESV (mL/m2) | |||

| 3–5 days | 57±14 | 57±14 | 0.30 |

| 4 months | 57±14 | 54±15 | 0.27 |

| 24 months | 52±21 | 61±23 | 0.02 |

| Infarct size (g)‡ at 3–5 days | 21±13 | 22±12 | 0.62 |

| Presence of MVO at 3–5 days | 42 (54%) | 48 (63%) | 0.33 |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction (%); LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; MVO, microvascular obstruction.

Table 3.

Follow-up of clinical outcomes and medication use until 5 years for study population split for change in left ventricular ejection fraction between 4 months and 24 months

| LVEF improvement (n=78%) |

LVEF deterioration (n=77%) |

p Value | |

| Medication at 4 months | |||

| ACE-inhibitors/ATII antagonists | 72 (92) | 69 (90) | 0.32 |

| Beta-blockers | 72 (92) | 69 (90) | 0.56 |

| Medication at 2 years | |||

| ACE-inhibitors/ATII antagonists | 73 (94) | 67 (87) | 0.35 |

| Beta-blockers | 75 (96) | 61 (80) | 0.004 |

| NYHA class I | |||

| 4 months | 63 (81) | 66 (86) | 0.41 |

| 2 years | 64 (82) | 70 (92) | 0.06 |

| Hospitalisation for heart failure | |||

| 2 years | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 0.56 |

| 5 years | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.56 |

| Repeat PCI | |||

| 2 years | 17 (21) | 16 (21) | 0.88 |

| 5 years | 18 (23) | 18 (23) | 1.00 |

| CABG | |||

| 2 years | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Recurrent myocardial infarction* | |||

| 5 years | 1 (1.3) | 3 (4) | 0.31 |

| Mortality* | |||

| 5 years | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.31 |

*Patients who died (n=3) or suffered recurrent myocardial infarction (n=4) in the first 24 months after PCI were not included in this substudy.

AT, angiotensin; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

SWT and remodelling

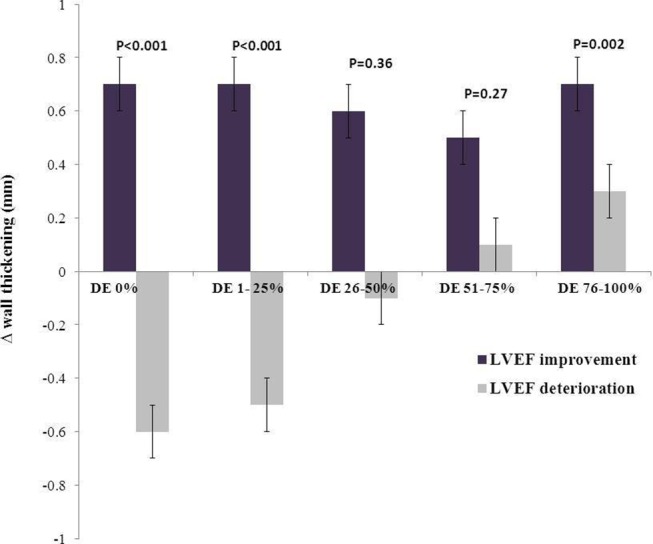

Segmental CMR analysis was used to gain more insight in the long-term remodelling process. Improvement in wall thickening (in mm) between 24 months and 4 months of follow-up was used to assess differences of infarct transmurality and subsequent positive or adverse LVEF changes. Therefore, in segmental CMR analysis, we assessed absolute wall thickening in millimetre per segment and categorised these segments according to the extent of transmurality (percentage DE). Change in wall thickening (mm) was significantly greater in patients with LVEF improvement compared with patients with LVEF deterioration (figure 1). Particularly, in segments with 0% or 1%–25% DE, the remote zone, this change in wall thickening was larger in patients with LVEF improvement compared with patients with LVEF deterioration.

Figure 1.

Change in wall thickening (in mm) between 24 and 4 months follow-up as assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging categorised for percentage of delayed enhancement and split for patients with LVEF improvement or deterioration. LVEF, – left ventricular ejection fraction; DE, delayed enhancement.

Discussion

The present study assesses the long-term functional outcome of patients with STEMI treated with primary PCI. There was a systematic use of secondary prevention treatment with beta-blockers and ACE inhibition to slow, or reverse cardiac remodelling after acute myocardial infarction.6–18 The main findings can be summarised as follows: (1) left ventricular function improvement after acute myocardial infarction is an ongoing process continuing up to 2 years follow-up, (2) long-term LVEF deterioration is characterised by an increase in end-systolic volume and less wall thickening in the remote zones, (3) patients with long-term LVEF improvement exhibit an increase in left ventricular wall thickening both in the transmural infarct and remote zones.

Left ventricular function improvement after acute myocardial infarction is a dynamic process continuing after 4 months of follow-up

This increase of LV volumes in the process of LV remodelling can be considered adaptive as it is an attempt to augment stroke volume and to maintain cardiac output. However, in patients with progressive postinfarction dilation, the end-systolic volume index increases progressively and LVEF declines. These changes are important predictors of mortality.19 20 There is accumulating evidence that left ventricular remodelling is a dynamic process occurring in the first weeks21 and months22–24 after myocardial infarction and in the long period thereafter.25–29 We demonstrated that left ventricular remodelling is a long-term process and is observed in the period between 4 and 24 months after STEMI. In the current study, remodelling was not influenced by secondary ischaemic events, as these patients were excluded from the analysis. To our knowledge, there are no other CMR studies that report the occurrence of long-term remodelling at 2 years. The magnitude of adverse remodelling at 4 months is related to infarct size and the presence of microvascular injury. In the current study, no difference in infarct size was observed in patients who developed deterioration in LVEF between 4 and 24 months. However, as previous studies demonstrated, infarct size and the presence of microvascular injury at baseline are associated with left ventricular function at 4 months following myocardial infarction.30–32

Long-term LVEF deterioration is characterised by an increase in end-systolic volume and less wall thickening in the remote zones

LVESV was significantly increased in patients with LVEF deterioration. In a prior study, LVESV has been reported as the strongest prognostic indicator for survival in post-STEMI patients.33 End-systolic volume is influenced by both end-diastolic volume and myocardial contraction. Impairment in LV function after an acute MI is induced by myocardial tissue necrosis in the infarct-related myocardium and by remote myocardial dysfunction.21 34 The remote myocardial dysfunction may explain why an AMI often exhibits a larger functional loss than expected solely on the basis of the extent of myocardial necrosis. Bogeart et al evaluated regional morphology and function in patients in their first week after having a reperfused anterior myocardial infarction.21 They demonstrated that changes in LV morphology and shape are found in the infarcted, adjacent and remote regions. The authors postulated that remote myocardial dysfunction is primarily caused by an impairment in the longitudinal and circumferential strains.35 Remote myocardial dysfunction could therefore be seen as secondary to morphological changes in the infarct region, leading to an increased systolic longitudinal wall stress. It has also been postulated that potential mechanisms for the initial decrease in wall thickening in remote and adjacent segments are coronary vasodilator abnormalities in the non-occluded arteries. Rademakers et al confirmed this phenomena describing it as an increase in loading condition of the adjacent myocardium.36 Other possible causes of decreased performance beside changes in load levels could relate to decreased intrinsic contractility, secondary to perfusion abnormalities at the microcirculatory level, possibly induced by overstimulation by catecholamines, inflammatory changes, altered regional neuro-adrenergic drive, and so on. Some of these mechanism are more likely to be at work in the infarct and adjacent regions, but they could also influence the remote zones. Of course, deterioration of the remote myocardium might not also be due to remodelling; instead chronic ischaemia resulting in hibernation can be the underlying cause.37 38 A functional assessment to exclude ischaemia may be essential to rule out this possibility.

Patients with long-term LVEF improvement exhibit an increase in left ventricular wall thickening both in the transmural infarct and remote zones

In animal models, there is an early increase in wall thickening in remote myocardial segments during the first weeks after reperfusion.6 The early increase in wall thickening as assessed by CMR in 22 patients with reperfused first-time MI confirmed these results.25 The authors found that the adjacent segments were found to recover primairly between 1 and 6 weeks after infarction. We confirmed these results in a larger population and with longer follow-up.

In summary, it has been suggested that the long-term remodelling process is driven by hypertrophic myocyte elongation in the non-infarcted zone, resulting in increase in wall mass and left ventricle enlargement. This is accompanied by a shift from an elliptical to a more spherical chamber configuration.4 7 39–44 These changes, together with a decline in performance of the pathologically hypertrophied myocyte and interstitial fibrosis within the non-infarcted zone, results in progressive decline in ventricular performance.45–49 This is in accordance with the current findings. We observed with segmental CMR analysis that patients with LVEF deterioration between 4 and 24 months follow-up had a significant decreased change in wall thickening (mm) compared with patients with LVEF improvement. Choi et al demonstrated that the transmural extent of infarction as defined by CMR predicts improvement in contractile function.24 We observed that these changes in wall thickening were observed both in the segments with transmural infarction (DE 76%–100%) and in the non-infarct or remote zone (DE 0% and DE 1%–25%). Moreover, the observed change in wall thickening in patients with LVEF improvement or deterioration was not dependent on infarct size and was similar in both groups. Patients showing LVEF improvement showed a significant increased wall thickening in the transmural segments compared with patients with LVEF deterioration. This may suggest that the defined cut of value for viability (75% transmurality as assessed by CMR) is questionable and needs more research as the infarct zone exhibits improvement at long-term follow-up.

Thus, the results of the current study show that LV remodelling, both positive and negative, is an ongoing process and continues at least up to 2 years after STEMI, involving the infarct zone and remote zones. Despite the fact that early remodelling may initially seem adaptive with early maintenance of cardiac output, this continuous remodelling process may only further deteriorate the LV with increased LV volumes and increased incidence of heart failure and cardiovascular death.

Limitations

In the current study, patients with relatively large infarcts (elevation of creatine kinase-myocardial band >10 times the ULN) were included. Therefore, the occurrence of adverse remodelling is likely higher than in a more general acute MI population. Patients who died (n=3) or received ICD (n=8) were excluded from this CMR analysis; these patients might represent the patients with the most extensive adverse remodelling. Also, we have no CMR data between 4 months and 24 months of follow-up. It is possible that the remodelling process continued for 6 or 12 months but then stopped. Lastly, in the current study, the remodelling process was only assessed by functional parameters assessed by CMR. Despite its clinical and prognostic importance, we do not provide any additional insights on the remodelling process at the histological level.

Conclusion

Cardiac remodelling is a dynamic and ongoing process up to 24 months following acute myocardial infarction. Long-term LVEF deterioration is characterised by an increase in end-systolic volume and less wall thickening in the remote zones. Patients with LVEF improvement exhibit an increase in left ventricular wall thickening both in the infarct as well as in the remote zones.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have contributed to the contents of the submitted manuscript. They read the final manuscript and agree with its submission.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant by the Dutch Heart Foundation. (Grant number NHS-2011T022) and the National Health Insurance Board/ZON MW (grant number 40-00703-98-11629) to RD.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Academic Medical Center.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.St John Sutton M, Pfeffer MA, Moye L, et al. . Cardiovascular death and left ventricular remodeling two years after myocardial infarction: baseline predictors and impact of long-term use of captopril: information from the survival and ventricular enlargement (SAVE) trial. Circulation 1997;96:3294–9. 10.1161/01.CIR.96.10.3294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opie LH, Commerford PJ, Gersh BJ, et al. . Controversies in ventricular remodelling. Lancet 2006;367:356–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68074-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling--concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. behalf of an International Forum on cardiac remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:569–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konstam MA, Kramer DG, Patel AR, et al. . Left ventricular remodeling in heart failure: current concepts in clinical significance and assessment. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:98–108. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch A, Nijveldt R, van der Vleuten PA, et al. . Intracoronary infusion of mononuclear cells from bone marrow or peripheral blood compared with standard therapy in patients after acute myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the randomized controlled HEBE trial. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1736–47. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Z, Berr SS, Gilson WD, et al. . Simultaneous evaluation of infarct size and cardiac function in intact mice by contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging reveals contractile dysfunction in noninfarcted regions early after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2004;109:1161–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118495.88442.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konstam MA, Kronenberg MW, Rousseau MF, et al. . Effects of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril on the long-term progression of left ventricular dilatation in patients with asymptomatic systolic dysfunction. SOLVD (Studies of left ventricular dysfunction) Investigators. Circulation 1993;88:2277–83. 10.1161/01.CIR.88.5.2277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber KT. Extracellular matrix remodeling in heart failure: a role for de novo angiotensin II generation. Circulation 1997;96:4065–82. 10.1161/01.CIR.96.11.4065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadoshima J, Jahn L, Takahashi T, et al. . Molecular characterization of the stretch-induced adaptation of cultured cardiac cells. an in vitro model of load-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Biol Chem 1992;267:10551–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindpaintner K, Lu W, Neidermajer N, et al. . Selective activation of cardiac angiotensinogen gene expression in post-infarction ventricular remodeling in the rat. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1993;25:133–43. 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharpe N, Murphy J, Smith H, et al. . Treatment of patients with symptomless left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Lancet 1988;1:255–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)90347-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfeffer MA, Lamas GA, Vaughan DE, et al. . Effect of captopril on progressive ventricular dilatation after anterior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1988;319:80–6. 10.1056/NEJM198807143190204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharpe N, Smith H, Murphy J, et al. . Early prevention of left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition. Lancet 1991;337:872–6. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90202-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basu S, Senior R, Raval U, et al. . Beneficial effects of intravenous and oral carvedilol treatment in acute myocardial infarction. A placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Circulation 1997;96:183–91. 10.1161/01.CIR.96.1.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doughty RN, Whalley GA, Gamble G, et al. . Left ventricular remodeling with carvedilol in patients with congestive heart failure due to ischemic heart disease. Australia-New Zealand Heart failure Research Collaborative Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;29:1060–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konstam MA, Rousseau MF, Kronenberg MW, et al. . Effects of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril on the long-term progression of left ventricular dysfunction in patients with heart failure. SOLVD investigators. Circulation 1992;86:431–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.86.2.431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konstam MA, Kronenberg MW, Rousseau MF, et al. . Effects of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril on the long-term progression of left ventricular dilatation in patients with asymptomatic systolic dysfunction. SOLVD (Studies of left ventricular dysfunction) Investigators. Circulation 1993;88:2277–83. 10.1161/01.CIR.88.5.2277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenberg B, Quinones MA, Koilpillai C, et al. . Effects of long-term enalapril therapy on cardiac structure and function in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. results of the SOLVD echocardiography substudy. Circulation 1995;91:2573–81. 10.1161/01.CIR.91.10.2573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spinelli L, Morisco C, Assante di Panzillo E, et al. . Reverse left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction: the prognostic impact of left ventricular global torsion. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;29:787–95. 10.1007/s10554-012-0159-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahn KT, Song YB, Choe YH, et al. . Impact of transmural necrosis on left ventricular remodeling and clinical outcomes in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;29:835–42. 10.1007/s10554-012-0155-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogaert J, Maes A, Van de Werf F, et al. . Functional recovery of subepicardial myocardial tissue in transmural myocardial infarction after successful reperfusion: an important contribution to the improvement of regional and global left ventricular function. Circulation 1999;99:36–43. 10.1161/01.CIR.99.1.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pokorney SD, Rodriguez JF, Ortiz JT, et al. . Infarct healing is a dynamic process following acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2012;14:62 10.1186/1532-429X-14-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savoye C, Equine O, Tricot O, et al. . Left ventricular remodeling after anterior wall acute myocardial infarction in modern clinical practice (from the REmodelage VEntriculaire [REVE] study group). Am J Cardiol 2006;98:1144–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi KM, Kim RJ, Gubernikoff G, et al. . Transmural extent of acute myocardial infarction predicts long-term improvement in contractile function. Circulation 2001;104:1101–7. 10.1161/hc3501.096798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engblom H, Hedström E, Heiberg E, et al. . Rapid initial reduction of hyperenhanced myocardium after reperfused first myocardial infarction suggests recovery of the peri-infarction zone: one-year follow-up by MRI. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:47–55. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.802199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerber BL, Garot J, Bluemke DA, et al. . Accuracy of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in predicting improvement of regional myocardial function in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2002;106:1083–9. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000027818.15792.1E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schroeder AP, Houlind K, Pedersen EM, et al. . Serial magnetic resonance imaging of global and regional left ventricular remodeling during 1 year after acute myocardial infarction. Cardiology 2001;96:106–14. 10.1159/000049092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichikawa Y, Sakuma H, Suzawa N, et al. . Late gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in acute and chronic myocardial infarction. improved prediction of regional myocardial contraction in the chronic state by measuring thickness of nonenhanced myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:901–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Springeling T, Kirschbaum SW, Rossi A, et al. . Late cardiac remodeling after primary percutaneous coronary intervention-five-year cardiac magnetic resonance imaging follow-up. Circ J 2013;77:81–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beek AM, Kühl HP, Bondarenko O, et al. . Delayed contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for the prediction of regional functional improvement after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:895–901. 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00835-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nijveldt R, Beek AM, Hirsch A, et al. . Functional recovery after acute myocardial infarction: comparison between angiography, electrocardiography, and cardiovascular magnetic resonance measures of microvascular injury. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:181–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solomon SD, Glynn RJ, Greaves S, et al. . Recovery of ventricular function after myocardial infarction in the reperfusion era: the healing and early afterload reducing therapy study. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:451–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-134-6-200103200-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White HD, Norris RM, Brown MA, et al. . Left ventricular end-systolic volume as the Major determinant of survival after recovery from myocardial infarction. Circulation 1987;76:44–51. 10.1161/01.CIR.76.1.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kramer CM, Rogers WJ, Theobald TM, et al. . Remote noninfarcted region dysfunction soon after first anterior myocardial infarction. A magnetic resonance tagging study. Circulation 1996;94:660–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.94.4.660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bogaert J, Bosmans H, Maes A, et al. . Remote myocardial dysfunction after acute anterior myocardial infarction: impact of left ventricular shape on regional function: a magnetic resonance myocardial tagging study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:1525–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rademakers F, Van de Werf F, Mortelmans L, et al. . Evolution of regional performance after an acute anterior myocardial infarction in humans using magnetic resonance tagging. J Physiol 2003;546:777–87. 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wijns W, Vatner SF, Camici PG. Hibernating myocardium. N Engl J Med 1998;339:173–81. 10.1056/NEJM199807163390307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carluccio E, Biagioli P, Alunni G, et al. . Patients with hibernating myocardium show altered left ventricular volumes and shape, which revert after revascularization: evidence that dyssynergy might directly induce cardiac remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:969–77. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell GF, Lamas GA, Vaughan DE, et al. . Left ventricular remodeling in the year after first anterior myocardial infarction: a quantitative analysis of contractile segment lengths and ventricular shape. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;19:1136–44. 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90314-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pouleur HG, Konstam MA, Udelson JE, et al. . Changes in ventricular volume, wall thickness and wall stress during progression of left ventricular dysfunction. the SOLVD investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22:A43–8. 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90462-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rumberger JA, Behrenbeck T, Breen JR, et al. . Nonparallel changes in global left ventricular chamber volume and muscle mass during the first year after transmural myocardial infarction in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;21:673–82. 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90100-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eaton LW, Weiss JL, Bulkley BH, et al. . Regional cardiac dilatation after acute myocardial infarction: recognition by two-dimensional echocardiography. N Engl J Med 1979;300:57–62. 10.1056/NEJM197901113000202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erlebacher JA, Weiss JL, Eaton LW, et al. . Late effects of acute infarct dilation on heart size: a two dimensional echocardiographic study. Am J Cardiol 1982;49:1120–6. 10.1016/0002-9149(82)90035-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKay RG, Pfeffer MA, Pasternak RC, et al. . Left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: a corollary to infarct expansion. Circulation 1986;74:693–702. 10.1161/01.CIR.74.4.693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E. Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. experimental observations and clinical implications. Circulation 1990;81:1161–72. 10.1161/01.CIR.81.4.1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White HD, Norris RM, Brown MA, et al. . Left ventricular end-systolic volume as the Major determinant of survival after recovery from myocardial infarction. Circulation 1987;76:44–51. 10.1161/01.CIR.76.1.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verma A, Meris A, Skali H, et al. . Prognostic implications of left ventricular mass and geometry following myocardial infarction: the VALIANT (VALsartan in acute myocardial iNfarcTion) Echocardiographic study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2008;1:582–91. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White HD, Norris RM, Brown MA, et al. . Left ventricular end-systolic volume as the Major determinant of survival after recovery from myocardial infarction. Circulation 1987;76:44–51. 10.1161/01.CIR.76.1.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee TH, Hamilton MA, Stevenson LW, et al. . Impact of left ventricular cavity size on survival in advanced heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1993;72:672–6. 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90883-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]