Abstract

Introduction

Oral health education/promotion interventions have been identified as cost-efficient tools to improve the oral health of the population. These interventions are regularly made in contexts where the target population is captive, for example, in health centres. In Chile, there are no oral health interventions delivered at home.

Methods and analysis

This community trial covers two disadvantaged urban areas in the province of Concepción. Both sectors have public preschool education coverage with a traditional programme (TP) to promote oral health. The intervention will comprise four to six visits by dental hygienists trained in the delivery of a standardised oral health promotion programme using motivational interviewing (MI) at home. The experimental group will receive TP and MI, while the control group will receive only TP. If a positive and significant effect of MI is found, this will be administered to the control group. For a 50% reduction in the incidence of caries, a sample size of 120 preschoolers per group is estimated. Data will be gathered on demographic and socioeconomic variables; oral health outcomes using WHO oral health indicators (the prevalence and severity of caries, periodontal disease, dentofacial anomalies and oral hygiene); the oral health literacy of caregivers, measured by the Rapid Estimation of Adult Literacy in Dentistry and the Oral Health Literacy Instrument, both validated for the Chilean population. Assessments will take place at baseline and at 12-month follow-up.

Ethics and dissemination

The university bioethics committee approved this study (EI/21/2014). We will submit the trial’s results for presentation at international scientific meetings and to peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12615000450516.

Keywords: Oral health literacy, Caries, Children, Home visits, Chile, Motivational interviewing.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This project seeks to involve the entire family or, at least, all caregivers, whereas other studies have focused only on mothers; to achieve this goal, the project introduces flexibility in the schedule of visits.

The incidence of caries between 2 and 4 years of age in this population is high, so these strategies could have a greater impact than those obtained in developed countries where incidence is lower.

This project will use validated instruments to measure oral health literacy, giving an objective measure of the intervention’s impact.

Most previous studies have been conducted by using continuous monitoring and contact with the patients, making it difficult to estimate the real impact of the pure intervention.

There are no home visits for the control group, which makes it difficult to assess the pure impact of the motivational interviewing intervention.

Introduction

Rationale

Dental caries remains one of the most prevalent chronic diseases in the world, demonstrating inequity in its distribution similar to other diseases. Worldwide, the disadvantaged population shows the greatest burden of oral disease.1 A specific aspect of this inequity is the increased prevalence and severity of early childhood caries. This is a point of concern in developed and in developing countries.2–4

To explain the development of dental caries in children, several models have been proposed. Fischer-Owens et al 5 proposed a conceptual model with five domains: genetic and biological factors, social environment, physical environment, health behaviours and medical and dental care. These factors interact at three levels: child, family and community, providing the opportunity to intervene at one or more points before the appearance of oral disease.

The biological domain has been historically addressed through the adoption of policies such as water fluoridation combined with other clinical preventative measures (eg, sealants and topical fluorinations). In recent years, however, research into psychosocial and behavioural aspects has increased, using a health-promotion approach.4 5

The practice of this new approach has been based on psychological theories seeking behaviour change in order to maintain and/or strengthen health.6 The most important of these include the Health Belief Model,7 the Stages of Change as a part of the Transtheoretical Model,8 9 the Theory of Reasoned Action,10 the concept of self-efficacy in Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory11 and the sense of coherence in the Salutogenic Model of Antonovsky.12

The central target of these theories is some form of health literacy (HL). HL is crucial; there is ample evidence indicating that low levels of HL is a risk factor for the appearance, perpetuation and aggravation of various diseases that bring functional, psychological, social and economic consequences.13

Oral health literacy (OHL) focuses on dental aspects.14 Research in OHL has been consistent with the findings regarding HL.15 Several studies have found an association between caregivers’ OHL and the oral health outcomes of their children in terms of the need for dental treatment,16 the use of dental sealants,17 oral health-related quality of life,18 deleterious habits19 and dental emergency expenses.20

Despite the above, promotional strategies focused on dental patients have only recently been considered.2–4 Motivational interviewing (MI) is a promotional strategy seeking to support and help a person in examining and resolving conflicting ideas, emotions and attitudes, thus facilitating an increase in the person’s awareness of the potential problems, consequences and risks through improvement of the intrinsic motivation to change and resolve ambivalence by means of steering a person-centred approach. The person is invited to verbalise what behaviour changes they are willing to make, focusing on the movement and commitment towards that change.21 MI has shown good results in different dental settings.2 4 22 23 However, these results are transitory and have negligible impact on the incidence of caries.22 24

Currently, there is scarce evidence on the effects of interventions delivered at home on OHL and the oral health outcomes of preschool children, although home visiting interventions have been successful in other child/pregnancy health outcomes.25–28 The Chilean Ministry of Health is implementing an oral health intervention for preschoolers in kindergartens,29 without plans (or evidence) to extend these programmes to home.

Objective and hypotheses

The main objective of this community trial is to evaluate at a 12-month follow-up the oral health impact, measured by the incidence of caries in preschoolers and OHL levels in caregivers, of an MI intervention delivered in the homes of disadvantaged families in Chile.

The hypotheses is that an MI intervention will achieve a decrease in the incidence of caries by 50% in preschoolers and an increase of OHL levels by 30% in caregivers at a 12-month follow-up. These values are based on previous studies using MI interventions2 4 23 24 and the criteria of our research group for what is a relevant improvement in the oral health status and OHL of this population.

Methods

Study design

This is a single blind community/cluster trial. The clusters or groups to be randomised will be the entire communities and not kindergartens or other smaller groups, as in similar research.2 3 This design was chosen because of the strong chance of contamination by the experimental group or the control group by some aspect of the MI intervention. The main chance of contamination could affect the children of the different groups attending different kindergartens but living close to one another, or their parents being related by family or friendship.

Since this intervention involves visiting the homes of the preschoolers, we may not achieve masking of patients or who delivered the MI intervention. The professionals who will remain blinded will comprise only those involved in the assessment at the 12-month follow-up.

The study does not include interim assessments because, considering the nature of the health promotional interventions, any contact or reminder to participants could act as a health intervention in itself.

Participants and selection criteria

Participants comprise preschoolers and their caregivers living in the communities of Boca Sur at San Pedro de la Paz (MI intervention) and Los Cerros at Talcahuano (control group). Both communities have similar characteristics in terms of size and socioeconomic conditions. Both show high levels of social vulnerability and are separated by approximately 25 km.

Participants must meet the following inclusion criteria: children aged between 2 and 4 years at the time of initiating the intervention, attending National Kindergarten Board, Junta Nacional de Jardines Infantiles (JUNJI) or Integra kindergartens in the communities mentioned above and with a family member in charge (caregiver). The JUNJI and Integra kindergartens are the main organisations delivering preschool education at national level in Chile; both work in alliance with the Chilean Ministry of Health in oral health issues.29

Exclusion criteria were preschoolers who are receiving dental treatment at the secondary level of care and children or caregivers presenting with any physical and/or mental conditions that preclude the delivery of the MI intervention.

Sample size

For the calculation of sample size, a design effect30 was considered based on an intracluster correlation coefficient (denoted as ρ) of 0.01. There are no data available for these communities, so we used a ρ of 0.009, as described in previous research,3 what had rounded up to 0.01 in this study.

Considering recent oral health research in similar Chilean groups of preschoolers,31–34 the 1-year incidence of caries, as assessed by the decay, missing, filled teeth (DMFT) index, and the SD were estimated at 4. Consequently, the goal was estimated at 2 in order to reduce by 50% the incidence of caries in the MI intervention group.

Therefore, the sample size estimation was made in four steps:

Student’s t-test for independent samples (two-sided, alpha=5%, power=80%, mean difference=2, SD=4) gave an number initial=64.

The design effect (de) is estimated as described elsewhere30 (1+(ni-1)ρ), giving a de=1.63.

Loss rate during follow-up is estimated at 15%.

The final sample size is calculated as: 64×1.63×1.15=120 preschoolers with their caregivers per group. The minimum sample size to assess at 12-month follow-up is therefore 104 preschoolers with their caregivers per group.

Patient recruitment

In order to obtain administrative support, all related institutions with the oral health of the preschoolers were contacted. The first contact was with the District Department of Health of San Pedro de la Paz and Talcahuano and the Province Office of Integra and JUNJI. All agreed to participate in the study.

Second, the directors of all kindergartens in the two communities were contacted. All agreed to participate in the study and authorised us to participate in the monthly caregivers’ meetings and/or to send invitations to preschoolers’ homes in order to inform caregivers about the study. To avoid expectation effects, we only provide basic information about the study and ethical issues.

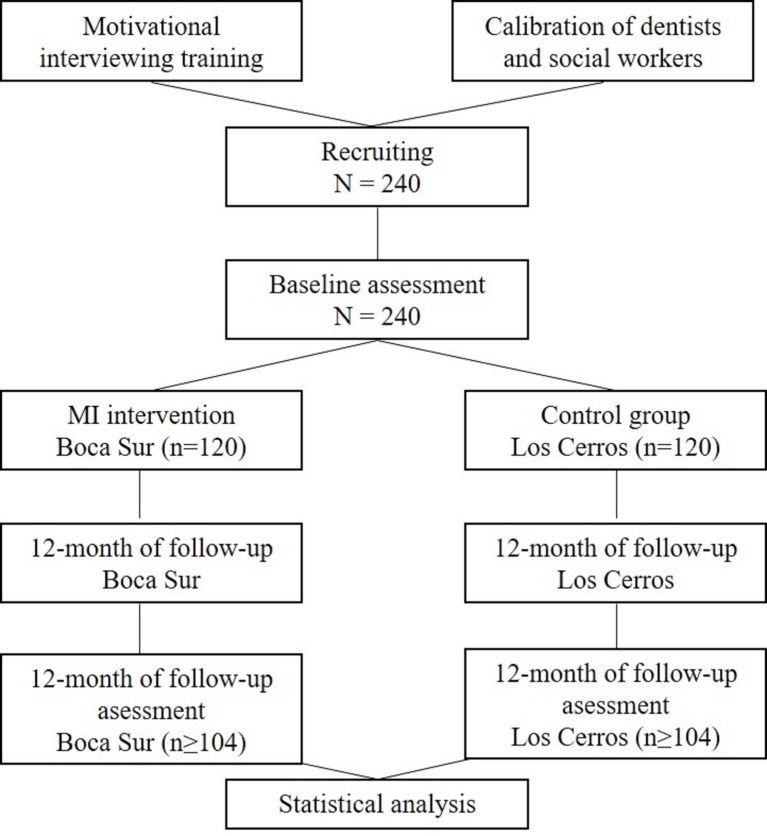

The information in the meetings will be delivered through a PowerPoint presentation, including the study’s aim, intervention, contacts and ethical considerations. The information in the invitations includes the same information as in the PowerPoint presentation, plus a date and time for data collection in the kindergartens or at the family health centre of the respective community. Patient recruitment will be stopped when the sample size is reached (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart.

Variables

The study includes three groups of variables: socioeconomic and demographics, oral health outcomes and OHL.

The socioeconomic and demographic variables will describe:

First, the household composition, with a description of the preschooler’s nuclear family using a genogram. The gender, age, occupation and level of education of each member will be included and the relationships between them.

Second, each household’s economic situation, with information on the income received by paid work of each member of the family and state aid received from social programmes (Puente, Chile Solidario and similar).

Oral health outcomes

Caries: Assessment was made using the International Caries Detection System Assessment (ICDAS). The ICDAS codes will be transformed to DMFT and DMFT indicators.

Periodontal disease: Assessment was made using the Community Periodontal Index in adults. For preschoolers, gingival inflammation was assessed at three levels: none, local and generalised.

Dentofacial anomalies: Assessment was made using the Dental Aesthetic Index in adults. This variable was not considered in preschoolers.

Oral hygiene: Assessment was made using the Oral Simplified Hygiene Index (OHI-S).

OHL: Assessment of caregivers’ OHL was made using two instruments.

The Oral Health Literacy Instrument (OHLI)35: This comprises 57 items, divided into a first section of 38 missing words in a paragraph (Cloze procedure) about tooth decay and periodontal disease and a second section of 19 items focused on numerical skills about medical prescriptions and instructions after dental procedures. For this study, a validated version of the OHLI for the Chilean population was used; this version shows a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.886 and an intraclass correlation coefficient of >0.6 for temporal stability (publication under peer review). These values are comparable to the original OHLI, which has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.854 and an intraclass correlation coefficient of >0.6.35

Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Dentistry, 30 items (REALD-30)36: This comprises 30 words from the American Dental Association Glossary of Common Dental Terminology and dental materials commonly available in dental clinics, arranged in order of increasing difficulty. For this study, a validated version of the OHLI for the Chilean population was used; this version shows a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.876 and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.789 for temporal stability (publication under peer review). These values are comparable to the original REALD-30, which has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87.36

Data collection

Data collection will be carried out at baseline (preintervention) and at a 12-month follow-up. An initial calibration will be made to assure the reliability of the data (see figure 1).

Calibration: The dentists and social workers will go through a calibration process consisting of an information day about the study and the instruments and indicators. Clinical calibration will be performed at the Universidad de Concepción School of Dentistry with a sample of 12 preschoolers and their caregivers, recruited from the family health centres of Concepción.

Baseline: All assessments will be made directly at the kindergartens or the family health centre of the respective community. The caregivers will be informed, and they will sign the informed consent form (see the Supplementary Appendix 1); the assent of the preschoolers will also be obtained. The study will accord with the conditions set by the WHO to carry oral health surveys.37

bmjopen-2016-011819supp001.pdf (295.2KB, pdf)

Each respondent (caregiver and preschooler) will be given an oral healthcare kit consisting of toothpaste and toothbrushes.

Data will be collected by a dentist and a dental assistant concerning oral health outcomes and a social worker for socioeconomic and demographic data and OHL.

12-month follow-up: All assessments will be made at the Universidad de Concepción School of Dentistry (approximately 20 km distant from both sectors). The procedure will be the same as in the baseline assessment, but the assessment will be made by professionals blinded to the allocation of the participant to the control or experimental group to assure the single blind of the trial (see figure 1).

Caregivers will be contacted by telephone to arrange an appointment for the follow-up assessment. Transportation and other associated expenses incurred by travel to and from the School of Dentistry will be compensated with CLP $10 000 (US$ 15). The caregiver will be instructed not to inform their community or indicate their group allocation to the professionals.

Training in MI

A training course will be carried out with a duration of 40 hours spread over 5 days. The course will have theoretical and practical sections and will be taught by an expert psychologist trained in MI courses delivered by the Ministry of Health, who has 10 years of experience delivering MI interventions. Two dentists with Master’s degrees in Public Health and experience in dental primary care help the psychologist by describing some typical scenarios of dental care and oral health promotion. Those who pass will receive a certificate from the Universidad de Concepción School of Dentistry.

Applicants for the course will be selected according to their professional background and an interview. The course will have a maximum availability of 12 places; all will be assigned a full scholarship by the School of Dentistry. Preference will be given to dental assistants and dental hygienists working in the family health centres of the participating communities.

Four students will be selected from those who pass the course and obtain the highest grades to apply the MI intervention.

Intervention

Both the MI intervention and the control group will receive oral health interventions at kindergartens using the programme ‘Sembrando Sonrisas’ (‘Sowing smiles’)29 of the Oral Health Department in the Ministry of Health.

The MI intervention in this study comprises four to six home visits with the following characteristics.

The visits follow the principles of MI21 that seek to generate motivation and goals from the client and not the delivery of advice by the health worker.

The visits will be adjusted to the needs of the families themselves, covering at least self-care and oral healthcare, as recommended by the Chilean Ministry of Health.29

The visits will be made by couples of dental hygienists previously trained in the delivery of a standardised oral health promotion through MI.

The visits will have a duration of 15–45 min; normally, the first visit will be longer.

Besides the MI, some materials will be given to families: a leaflet about oral health, a dental colouring book with crayons, a Colgate Dr Rabbit DVD, stickers to remind participants about toothbrushing and four to six plaque disclosing tablets to check the toothbrushing. We do not give these materials to the control group, but similar materials are given to both groups by the programme ‘Sembrando Sonrisas’ (‘Sowing smiles’) of the Oral Health Department in the Ministry of Health.

The first visit will take place during the 3 weeks after the baseline assessment. The appointment for the remaining three to five visits will be agreed with each family, separated by 7–14 days.

The times and days of the visits will be adjusted to the availability of families, trying to ensure the participation of the preschooler’s caregivers, within a schedule from 8.00 to 21.00 hours from Monday to Saturday.

Statistical analysis

Univariate description of all variables (baseline and follow-up) will be performed using frequency tables (qualitative variables), summary measures (of central tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables), accompanied by relevant graphics (pie charts, bars and histograms).

Regarding the psychometric properties of OHLI and REALD-30, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency of the scales will be used. Regarding the calibration of the dentists and social workers, the strength of agreement will be determined with Kappa or Lin coefficients, depending on the nature of the variables.

To analyse the association between qualitative variables, the χ2 test will be used and for the association of quantitative variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient. To compare the incidence of caries and changes in the level of OHL (intervention effect), the analysis of covariance and multiple linear regression models will be used. In both cases, relevant confounding variables2–5 14–20 will be considered: sex, parents’ age, parents’ education level, child’s age, monthly per capita income and baseline values for caries and OHL. If the necessary assumptions for parametric tests are not met, the corresponding non-parametric tests will be used.

Statistical significance will be set at p<0.05. The analysis will be made with Stata/SE V.14 for Windows (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical considerations

The study adheres strictly to the Declaration of Helsinki,38 as well as the Chilean laws #20 120 (research in humans),39 and #20 584 (rights and duties of the patient).40

All patients are informed about the aim of the study and they will give their informed consent (see the Supplementary Appendix 1) in order to participate in the study.

If a positive and significant effect of the MI intervention is found, this will be administered to the control group.

Dissemination

We will submit the trial’s results for presentation at international scientific meetings and to peer-reviewed journals. The statistical codes and anonymised data will be freely available on request to corresponding author.

Discussion

In many developed countries, there is concern about the increase in the prevalence and severity of early childhood caries.2–4 Caries in preschoolers is associated not only with high expense, but a strong functional, aesthetic and psychological impact on the children and their families.41 Previous studies in disadvantaged communities of Chile show that the prevalence and severity of early childhood caries is high,34–37 so strategies are needed to address it.

This project is motivated by the development, assessment and (prospective) implementation in Chile of new strategies to promote oral health. The target population is preschool children of disadvantaged communities of Chile, as other similar populations across the world. This is a great challenge, considering that most public health interventions have had little impact on inequities in oral health at national41 42 and worldwide level.1 43 44 Bearing these difficulties in mind, a proactive approach is proposed, delivering oral health promotion directly to the home. This approach is based on the positive results of home visits in other health areas.25–28

Nowadays in Chile, the promotional aspect of oral healthcare is a secondary component of curative and preventative care. Most oral healthcare is delivered to specific groups (population aged 6, 12 and 60 years, pregnant women and those requiring urgent dental care) through the Explicit Health Guarantees, Garantías Explícitas en Salud (GES) programme).41 Recently, an oral health intervention at the JUNJI and Integra’s kindergartens using the programme ‘Sembrando Sonrisas’ has been introduced.29 This intervention is focused on achieving better results in the oral health status of children when they are enrolled in the GES programme at 6 years of age.

However, there are no explicit programmes involving caregivers in the oral healthcare of their children in Chile, despite the good results of a mother–child preventative dental programme developed in the country.45 The evidence suggests that if the adults responsible for the care of children are not committed, qualified and empowered with strategies to reinforce learning at home,15–20 behavioural interventions performed at the schools are insufficient to improve the children’s oral health.46 Within this context, there is a need to develop cost-effective interventions that impact on adult OHL in order to continue the virtuous circle started at the school or the kindergarten; otherwise, school-based interventions could be useless.

At the international level, many studies have been developed to assess strategies to promote oral health through MI2–4 21–24 and home visits25–28 aimed at the disadvantaged population. However, they have all been conducted in developed countries, namely, Australia,2 4 Canada3 and the USA.24 To our knowledge, there are no studies published from Latin American countries or other populations with similar socioeconomic and idiosyncratic conditions.

Despite the similarities with studies in developed countries, there are some relevant differences to mention: (a) this project seeks to involve the entire family or, at least, all caregivers, whereas other studies have focused only on mothers; to achieve this goal, the project introduces flexibility in the schedule of visits, (b) other studies have used a low number of visits; in this study, a minimum of four and a maximum of six visits over 3–10 weeks is planned, (c) the incidence of caries between 2 and 4 years of age in this population is high, so these strategies could have a greater impact than those obtained in developed countries where incidence is lower, (d) this project will use validated instruments to measure OHL, giving a objective measure of the intervention’s impact on OHL and (e) most previous studies have been conducted by using continuous monitoring and contact with the patients, making it difficult to estimate the real impact of the isolated intervention due to the implicit Hawthorne effect.47

In Chile, previous research on this matter has focused on preventative oral healthcare from pregnancy up to 10 years later.45 However, there are some issues not addressed by this approach: (a) a large proportion of the preschool Chilean population has not been followed from pregnancy, (b) interventions have been used with mother–child dyads, omitting fathers or other caregivers and (c) the promotional aspect of the intervention focuses on prescribing the ‘right behaviour’; this has little impact on oral health and the empowerment of the population.6

In summary, the main innovation of this study is the thorough assessment of an MI intervention at the community level, involving the caregivers of preschoolers in disadvantaged communities. Although this is the first trial of this intervention in a Latin American country, the recommendations generated from similar studies in disadvantaged populations of developed countries have been considered. This community trial will provide local evidence on the effectiveness on MIs in improving oral health outcomes and literacy in our disadvantaged population.

bmjopen-2016-011819supp002.doc (124KB, doc)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @cartesvelasquez

Contributors: All authors designed the study. LL provided statistical advice. RCV and RF wrote the manuscript. All authors proofed and edited the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the Fondo Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo en Salud (FONIS) N° SA14ID0162, Gobierno de Chile (National Fund for Health Research and Development, Chilean Government). The validation study of REALD-30 and OHLI used in this study is funded by the Proyecto de Iniciación de la Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Desarrollo (VRID) N° 214.089.005-1.OIN, Universidad de Concepción. Funders have no role in study design; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report and the decision to submit the report for publication. Funder contact: Ms Ximena González, email: xgonzalez@conicyt.cl.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Appendix 1

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Universidad de Concepción School of Medicine with the code EI/21/2014.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hosseinpoor AR, Itani L, Petersen PE. Socio-economic inequality in oral healthcare coverage: results from the World Health Survey. J Dent Res 2012;91:275–81. 10.1177/0022034511432341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arrow P, Raheb J, Miller M. Brief oral health promotion intervention among parents of young children to reduce early childhood dental decay. BMC Public Health 2013;13:245. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harrison RL, Veronneau J, Leroux B. Effectiveness of maternal counseling in reducing caries in Cree children. J Dent Res 2012;91:1032–7. 10.1177/0022034512459758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Plutzer K, Spencer AJ. Efficacy of an oral health promotion intervention in the prevention of early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2008;36:335–46. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fisher-Owens SA, Gansky SA, Platt LJ, et al. Influences on children's oral health: a conceptual model. Pediatrics 2007;120:e510–20. 10.1542/peds.2006-3084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hollister MC, Anema MG. Health behavior models and oral health: a review. J Dent Hyg 2004;78:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walker K, Jackson R. The health belief model and determinants of oral hygiene practices and beliefs in preteen children: a pilot study. Pediatr Dent 2015;37:40–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wade KJ, Coates DE, Gauld RD, et al. Oral hygiene behaviours and readiness to change using the TransTheoretical Model (TTM). N Z Dent J 2013;109:64–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jamieson LM, Armfield JM, Parker EJ, et al. Development and evaluation of the stages of change in oral health instrument. Int Dent J 2014;64:269–77. 10.1111/idj.12119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jönsson B, Baker SR, Lindberg P, et al. Factors influencing oral hygiene behaviour and gingival outcomes 3 and 12 months after initial periodontal treatment: an exploratory test of an extended Theory of Reasoned Action. J Clin Periodontol 2012;39:138–44. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01822.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jones K, Parker EJ, Steffens MA, et al. Development and psychometric validation of social cognitive theory scales in an oral health context. Aust N Z J Public Health 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peker K, Bermek G, Uysal O. Factors related to sense of coherence among dental students at Istanbul University. J Dent Educ 2012;76:774–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:2072–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Naghibi Sistani MM, Yazdani R, Virtanen J, et al. Determinants of oral health: does oral health literacy matter? ISRN Dent 2013;2013:1–6. 10.1155/2013/249591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee JY, Divaris K, Baker AD, et al. The relationship of oral health literacy and self-efficacy with oral health status and dental neglect. Am J Public Health 2012;102:923–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miller E, Lee JY, DeWalt DA, et al. Impact of caregiver literacy on children's oral health outcomes. Pediatrics 2010;126:107–14. 10.1542/peds.2009-2887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mejia GC, Weintraub JA, Cheng NF, et al. Language and literacy relate to lack of children's dental sealant use. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2011;39:318–24. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00599.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Divaris K, Lee JY, Baker AD, et al. Caregivers' oral health literacy and their young children's oral health-related quality-of-life. Acta Odontol Scand 2012;70:390–7. 10.3109/00016357.2011.629627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vann WF, Lee JY, Baker D, et al. Oral health literacy among female caregivers: impact on oral health outcomes in early childhood. J Dent Res 2010;89:1395–400. 10.1177/0022034510379601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vann WF, Divaris K, Gizlice Z, et al. Caregivers’ health literacy and their young children's oral-health-related expenditures. J Dent Res 2013;92:S55–62. 10.1177/0022034513484335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Croffoot C, Krust Bray K, Black MA, et al. Evaluating the effects of coaching to improve motivational interviewing skills of dental hygiene students. J Dent Hyg 2010;84:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brukiene V, Aleksejūniene J. An overview of oral health promotion in adolescents. Int J Paediatr Dent 2009;19:163–71. 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2008.00954.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jönsson B, Ohrn K, Oscarson N, et al. The effectiveness of an individually tailored oral health educational programme on oral hygiene behaviour in patients with periodontal disease: a blinded randomized-controlled clinical trial (one-year follow-up). J Clin Periodontol 2009;36:1025–34. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01453.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ismail AI, Ondersma S, Jedele JM, et al. Evaluation of a brief tailored motivational intervention to prevent early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2011;39:433–48. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00613.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peacock S, Konrad S, Watson E, et al. Effectiveness of home visiting programs on child outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Avellar SA, Supplee LH. Effectiveness of home visiting in improving child health and reducing child maltreatment. Pediatrics 2013;132:S90–S99. 10.1542/peds.2013-1021G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goyal NK, Teeters A, Ammerman RT. Home visiting and outcomes of preterm infants: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2013;132:502–16. 10.1542/peds.2013-0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, Harwood JM, et al. Outcomes of home visits for pregnant mothers and their infants: a cluster randomized controlled trial. AIDS 2013;27:1461–71. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283601b53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sembrando sonrisas. Ministerio de Salud. Gobierno de Chile http://web.minsal.cl/sembrando-sonrisas/, 2015. (accessed 06 Mar 2015).

- 30. Rutterford C, Copas A, Eldridge S. Methods for sample size determination in cluster randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:1051–67. 10.1093/ije/dyv113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cartes-Velásquez R, Araya N, Avilés A. Parafunciones y caries dentales en preescolares de comunidades pehuenches. Rev Cubana Estomatol 2012;49:295–304. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rivera C. Pre-school child oral health in a rural chilean community. Int J Odontostomatol 2011;5:83–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Uribe S, Rodríguez M, Pigna G, et al. Prevalencia de caries temprana de la infancia en zona rural del sur de Chile, 2013. Ciencia Odontol 2013;10:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yévenes I, Bustos BC, Ramos AA, et al. Prevalence of dental caries in preschool children in Peñaflor, Santiago, Chile. Rev Odonto Ciência 2009;24:116–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sabbahi DA, Lawrence HP, Limeback H, et al. Development and evaluation of an oral health literacy instrument for adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2009;37:451–62. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00490.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee JY, Rozier RG, Lee SY, et al. Development of a word recognition instrument to test health literacy in dentistry: the REALD-30–a brief communication. J Public Health Dent 2007;67:94–8. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. World Health Organisation. Oral health surveys: basic methods. 5th edition Ginebra: WHO, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kottow M. Consideraciones bioéticas sobre la Ley de derechos y deberes en atención de salud. Cuad Méd Soc 2011;52:22–7. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lavados M. La investigación biomédica en el contexto de la Ley N° 20.584. Rev Chil Neuropsiquiatr 2014;52:69–72. 10.4067/S0717-92272014000200001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martins-Júnior PA, Vieira-Andrade RG, Corrêa-Faria P, et al. Impact of early childhood caries on the oral health-related quality of life of preschool children and their parents. Caries Res 2013;47:211–8. 10.1159/000345534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cornejo-Ovalle M, Paraje G, Vásquez-Lavín F, et al. Changes in socioeconomic inequalities in the use of dental care following Major healthcare reform in Chile, 2004–2009. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:2823–36. 10.3390/ijerph120302823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cornejo-Ovalle M. [About socioeconomic inequalities in dental care in Chile]. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2014;35:78–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Palència L, Espelt A, Cornejo-Ovalle M, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in the use of dental care services in Europe: what is the role of public coverage? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2014;42:97–105. 10.1111/cdoe.12056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gomez SS, Emilson CG, Weber AA, et al. Prolonged effect of a mother-child caries preventive program on dental caries in the permanent 1st molars in 9 to 10-year-old children. Acta Odontol Scand 2007;65:271–4. 10.1080/00016350701586647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cooper AM, O'Malley LA, Elison SN, et al. Primary school-based behavioural interventions for preventing caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;5:CD009378. 10.1002/14651858.CD009378.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen LF, Vander Weg MW, Hofmann DA, et al. The Hawthorne effect in infection prevention and epidemiology. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015;36:1444–50. 10.1017/ice.2015.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011819supp001.pdf (295.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-011819supp002.doc (124KB, doc)