Abstract

Introduction

In order to reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors, a healthy diet must include dietary antioxidants from different sources (eg, Spirulina maxima) and regular practice of exercise should be promoted. There is some evidence from animal studies that S. maxima and exercise decrease cardiovascular disease risks factors. However, very few studies have proved the independent or synergistic effect of S. maxima plus exercise in humans. This study attempts to address the independent and synergistic effects in overweight and obese subjects participating in a systematic physical exercise programme at moderate intensity on general fitness, plasma lipid profile and antioxidant capacity.

Methods and analysis

Using a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, counterbalanced crossover study design, 80 healthy overweight and obese subjects will be evaluated during a 12-week isoenergetic diet accompanied by 4.5 g/day S. maxima intake and/or a physical systematic exercise programme at moderate intensity. Body composition, oxygen uptake, heart rate, capillary blood lactate, plasma concentrations of triacylglycerols, total, low-density and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, antioxidant status, lipid oxidation, protein carbonyls, superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase and paraoxonase will be assessed.

Ethics and dissemination

This study and all the procedures have been approved by the Universidad Autonoma de Ciudad Juarez Bioethics Committee. Findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, national and international conferences.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02837666.

Keywords: spirulina, dyslipidemias, oxidative stress, exercise, body fat, antioxidant

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Working with obese people, one of the main risk factors for cardiovascular diseases.

This study can be extrapolated to different populations.

Double-blind randomised controlled trial.

There are no possible limitations to perform all the procedures described in the present paper.

Background

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the leading causes of death worldwide. Each year, 17.5 million people die because of these diseases.1 Dyslipidaemias are a predisposing factor for CVD and are characterised by high concentrations of triacylglycerols (TAG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) and low concentrations of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c).2 Besides dyslipidaemias, oxidative stress (OxS) is also observed to rise in obesity,3 4 and it is also a predisposing factor for CVD.5–8

In order to reduce OxS, dyslipidaemias and the incidence of CVD, the intake of antioxidants from a fruit and vegetable-rich diet or nutritional supplements, mainly by unprocessed foods, has been proposed.9 10 In this sense, the cyanobacterium Spirulina is an important source of antioxidants, currently associated with cardiovascular protection properties.9 11

For centuries Spirulina maxima (S. maxima) has been cultivated and used as a nutritional supplement due to its content of amino acids and essential fatty acids, vitamin C, vitamin E, tocopherols and phycocyanins.12 Recently, studies on S. maxima have focused on verifying the biological activity of its components, including hypolipidaemic and antioxidant effects.13–15 However, most studies have been conducted in animal models, with only a few studies focused on the biological effect in humans.

Furthermore, it is known that the practice of systematic physical exercise ameliorates the risk of CVD,10 16 and it has been observed that it also plays a role in OxS, especially physical exercise at high intensity (PEHI).17 PEHI considerably increases general metabolism, oxygen uptake (VO2) and mitochondrial activity, thus increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).18 However, physical exercise of moderate intensity (PEMI) has the best protective effect against CVD, mainly due to physiological adaptations including the expression of antioxidant enzymes,19 which stop the formation and propagation of ROS and improving the redox status of the organism.20 21

Algae and cyanobacteria have shown promising pharmacological properties providing health benefits and physical improvements.22 These effects are attributed to their specific profile in bioactive compounds such as uncommon carotenoids, phenolic compounds and tocopherols in addition to their well-known content in vitamins and good quality proteins associated with their specific chemical structure and interaction with biological membranes.23

There is evidence that the cyanobacteria Spirulina, in addition to exercise, lowers the risks of CVD. This has mainly been observed in animal models.24–26 No studies with Spirulina and exercise experimental designs proving these benefits have yet been reported in humans. Therefore, the ISESE study will analyse the independent and synergistic effects of the intake of S. maxima with PEMI on general fitness, plasma lipid profile and redox status in overweight and obese subjects.

Methods/design

Hypothesis

Spirulina maxima intake and a dosed physical activity programme will improve the lipid profile, general fitness and antioxidant status in overweight and obese subjects.

Objectives

The ISESE project’s main objective is to demonstrate that ingestion of S. maxima and a dosed physical activity programme will decrease, both independently and synergistically, some CVD risks in overweight and obese subjects.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure will be changes in the plasma lipid profile after 6 weeks of treatment (plasma TAG, TC, HDL-c and LDL-c using standardised enzymatic methods).

The secondary outcome measure will be changes in general fitness (maximal oxygen uptake (VO2 max), heart rate (HR), onset blood lactate accumulation and body fat mass) as well as changes in redox status (malondialdehyde (MDA), protein carbonyls, paraoxonase (PON1), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase glutathione (GSH), glutathione reductase (GR) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx)).

Participant eligibility

The inclusion criteria will be subjects aged 18–45 years of both sexes: 40 overweight (body mass index (BMI) 25–29.9 kg/m2) and 40 obese (BMI >30 kg/m2). The exclusion criteria will be alcohol intake of >100 mL alcohol a week, taking drugs and/or food or vitamin supplements, diabetes or a physical or ECG injury that prevents engagement in any regular physical exercise. The elimination criteria will be attendance by the subject of <80% and/or 20% change in body weight during the study.

Enrolment, ethics and safety procedures

Overweight and obese students at the University of Ciudad Juarez, Mexico will be personally invited to participate. Participants will be informed of the purpose of the study and of the physical, clinical and biochemical procedures, benefits, physical intensity tests and risks before beginning the clinical trial. To guarantee the good physical and mental health of the participants at the beginning of the studies, a medical clinical laboratory study examination and an ECG at rest will be performed. The investigators are trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and the laboratory has the necessary communication tools and channels to perform emergency procedures. This study and all the procedures have been registered appropriately in the ClinicalTrials.gov database (NCT02837666) and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Universidad Autonoma de Ciudad Juarez (see online Supplementary file). Participants’ acceptance will be formalised by means of written informed consent and their anonymity and confidentiality will be strictly enforced. This study will be conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Baseline measurements

On the day before beginning the treatment, subjects will visit the laboratory for baseline measurements. Body mass will be measured with subjects lightly dressed and barefoot using an electronic balance and standing height with a stadiometer. Body fat percentage will be measured by plethysmography (BodPod, COSMED, Rome, Italy), electric bioimpedance (in body160, BIOSPACE, Japan) and by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (Prodigy v6.8; GE Lunar, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) according to the manufacturers' guidelines. Anthropometric parameters will be taken by the standardised method of the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK) and according to the ISAK Anthropometry Accreditation protocols.27 Researchers are experienced in handling equipment and procedures.

Study design

The study consists of S. maxima treatment for 14 weeks in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, counterbalanced crossover design aimed to eliminate interindividual bias as well as improve the reliability of the final results. This design is commonly used in clinical trials in order to have better results and conclusions.28 Eligible participants (n=80) will be divided into two groups, one with systematic practice of physical exercise (GEx) and the other without it (GNEx). The participants of each group will be randomised in equal proportions between S. maxima and placebo treatment, 4.5 g daily in a non-transparent capsule for 12 weeks (6 weeks of the first treatment followed by a 2-week washout period, then 6 weeks of the second treatment) (figure 1). If any reported allergic reaction occurs the treatment will be discontinued.

Figure 1.

Experimental design for independent and synergistic effect of Spirulina maxima and exercise. Same colour indicates the same group of participants.

To maintain the overall quality and legitimacy of the clinical trial, code interruptions should occur only in exceptional circumstances when knowledge of the actual treatment is essential for further management of the participant. Investigators are encouraged to discuss with a medical advisor if they believe that unblinding is necessary. Unblinding should not necessarily be a reason for study discontinuation.

A student outside the research team will feed data into the computer in separate datasheets so that the researchers can analyse the data without having access to information about the allocation treatments, storing all the participants’ files in numerical order in a safe and accessible place. The participants´ files will be stored for a period of 5 years after the end of the study.

The sample size was determined using the statistical programme G*Power,29 selecting a sample of 73 subjects with α=0.05 and p=0.85. This sample will be fixed to 80 subjects in order to anticipate possible withdrawals from the study.

Maximum intensity tests (MITs)

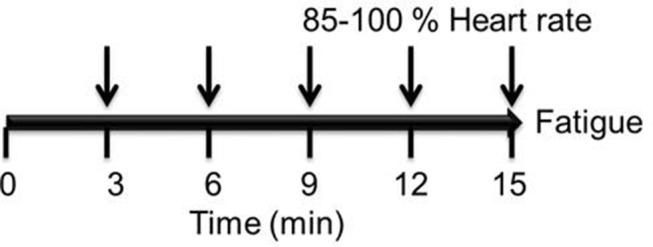

Each subject will participate in four stress tests performed at maximum intensity (MIT) during the study. During the MITs, oxygen consumed and carbon dioxide produced will be measured by a gas analyser (Cortex MetaLyzer 3B, Germany), HR with a Polar H7 sensor (Polar Electro, Lake Success, NY) and lactate in capillary blood samples will be assayed in a YSI 1500 Sport Lactate Analyzer (YSI Life Sciences, Ohio, USA). The MIT protocol consists of using a cycle ergometer (Monark Ergomedic 828 E; Monark Exercise AB, 105 Vansbro, Sweden) starting with a workload of 50–75 W with increments of 15–30 W every 3 min for 15 min or when the subject can no longer pedal more than 40 revolutions/min, finishing the test when 85–100% of the maximum HR reserve is reached. The MIT will not be valid if it lasts for less than 9 min (figure 2). At the end of each increment load (3 min), capillary blood samples will be taken to determine lactate and the physical perceived effort will be registered using the Borg scale. Measurements of HR, glucose and blood pressure will serve to check the subject’s health during each MIT.

Figure 2.

Design of maximum intensity tests. ↓ indicates the interval at which the resistance will be increased; in addition, physical perceived effort, heart rate and capillary blood samples will be measured.

Before the first MIT, subjects will decide to be in the GEx or GNEx and will then be divided randomly for treatment, consisting of a daily dose of 4.5 g of Spirulina or placebo in capsules which the subjects will be recommended to consume before each meal every day for 6 weeks. The day after the first supplementation period, subjects will come back to perform the second MIT with identical conditions to the first one. The third MIT will be performed after a washout period of 2 weeks to remove the effects of treatment and to avoid any possible delayed effect of S. maxima in the organism. The last MIT will be performed after the second treatment with identical conditions to the previous three occasions. General fitness parameters will be measured on the same day as the MITs to obtain accurate results.

Randomisation

All subjects who consent to participate and who meet the inclusion criteria will be randomly assigned by an investigator who will not have any other involvement in the clinical study; he will create a database with all the treatments throughout the duration of the study. Randomisation will therefore be carried out without any influence of the principal investigators. Participants will be randomly assigned to S. maxima or placebo treatment with a 1:1 allocation according to a computer-generated random schedule stratified by site and the baseline score of the Action Arm Research Test using permuted blocks of random sizes with an online central randomisation service (TENALEA). Block sizes will not be disclosed to ensure concealment.

Adherence assessments

Multiple methods will be used to assess treatment adherence including pill counting, reasons for non-compliance and use of the capsules. Participants will return each week to receive new capsules. All treatment data will be recorded on the appropriate case report form.

Dietary analysis

All participants will be subjected to a nutritional survey to define the daily calories required to establish a custom diet. Dietary intake will be monitored by retrospective methods including 24-hour recall (which investigates intake over a specific day) and a food frequency questionnaire (a summary of usual intake of different categories of foods). These accurate and validated techniques allow quantification of the types and quantities of foods and beverages consumed during the period of interest in the past. Dietary intake evaluations will be performed at each MIT of the study in order to record the possible variability in food consumption patterns.

Physical exercise protocol

General health assessment and physical activity questionnaires (PAR-Q and YOU) will be conducted to ensure that there are no physical impediments to exercise. GEx participants will exercise 5 days a week with the following protocol: 5–10 min of warm-up exercise, 20–30 min muscular endurance exercise and 20–30 min of aerobic exercise (cardiovascular exercise): walking, jogging, running and/or cycling. Three days a week aerobic intensities will be between 60% and 80% and 2 days between 70% and 90% of the maximum HR reserve, and five final minutes of stretching.

Sample collection and biochemical analysis

Blood samples (8 mL) will be collected before and after each MIT from the antecubital vein into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes after 10–12 hours of fasting; plasma will be obtained from the blood samples by refrigerated centrifugation (4°C) at 5000 g for 10 min. Plasma glucose TC, HDL-c, LDL-c and TAG concentrations will be analysed using standard enzymatic procedures (Jas Diagnostics, Mexico) with a spectrophotometer (Genesys 10 UV; Thermo Electron Corporation, USA). Plasma will be used to measure MDA and GSH content and activity of GPx and GR according to Jimenez-Osorio et al,30 total antioxidant status (TAS) by the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) technique as previously described by Koren et al,31 and oxygen radical absorbance capacity following the methodology of Prior et al.32 The erythrocytes will be washed twice with cold 0.9% saline solution and used for SOD and catalase activity assays, as previously described by Jimenez-Osorio et al.30 Plasma PON1 content will be measured following the method of Perez-Herrera et al.33

Statistical analysis

To evaluate data distribution, normality and homoscedasticity tests will be conducted on each of the response variables analysed. In order to analyse differences between variables before and after the study and between the groups, an ANOVA test will be performed. To analyse possible associations between variables, a bivariate correlation analysis will be used. To analyse independence between variables, a multiple regression analysis will be performed. The software to be used is GraphPad Prism 6.

Discussion

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of mortality worldwide, with OxS, overweight, obesity and dyslipidaemias being the main risk factors. Many of the drugs aimed at reducing these risk factors often have collateral side effects when used, and many people often use complementary medicine instead. For this and other reasons, the pharmacological industry has focused on developing new treatment options.34 S. maxima research has proven benefits to reduce CVD risk factors, alone or in combination with systematic practice of physical exercise, mainly in animal models.9 35 36

The experimental design, procedures, compliance with ethical principles and statistical analyses of the study are summarised and described. Because of the double-blind design, the methodology described and a higher number of participants than other studies, it is expected to achieve better support for the hypothesis that S. maxima will have hypolipidaemic and antioxidant effects against intense exercise and obesity. It is noteworthy that not every overweight or obese patient has problems with lipid metabolism. Nowadays the association between the augmentation of body fat and lipid disturbances is well known.37 For that reason, the primary focus of this protocol is prevention, which is why we do not consider dyslipidaemia as an inclusion criterion even though it could present in this condition.

Finally, it is known that the systematic practice of exercise and a balanced diet favours reduction of weight in obese people and generally decreases cardiometabolic risks,2 so it probably generates an increase in antioxidant capacity.38 However, no studies on the decrease in metabolic oxidation by the administration of Spirulina in obese people have been identified. Well-designed trials are needed to clarify the value of S. maxima supplementation in clinical practice39 and its complementary effect with or without exercise against dyslipidaemias and OxS in overweight and obese people, a fact almost unknown at this time.40 This establishes the importance of this study.

bmjopen-2016-013744supp001.pdf (89.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013744supp002.jpg (276.1KB, jpg)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Universidad Autonoma de Ciudad Juarez Institutional Bioethics Committee for the interest in this study, approving it and all its procedures. We also thank the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (CONACyT) for providing a scholarship to tMAHL.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the development of the study protocol and to the critical revision of the paper and approved the final version. RPHT, ARJ and JALD will be involved in patient recruitment; MAHL and AWM will analyse the data; MAHL and MAJO will do the lipid profile analyses; RUR, ARJ and MAHL will do the body composition measurements of all patients; LARC and JPC will do all the redox status analyses.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Universidad Autonoma de Ciudad Juarez Bioethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The protocol is an unpublished manuscript and is not under consideration by any other journal.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Factsheet No 317, 2015. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/ (accessed 9 Nov 2015).

- 2.Genest J, Frohlich J, Fodor G, et al. Recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia and the prevention of cardiovascular disease: summary of the 2003 update. CMAJ 2003;169:921–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet 2002;360:473–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09678-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, et al. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest 2004;114:1752–61. 10.1172/JCI21625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li S, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, et al. Childhood cardiovascular risk factors and carotid vascular changes in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. JAMA 2003;290:2271–6. 10.1001/jama.290.17.2271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halliwell B, Cross CE. Oxygen-derived species: their relation to human disease and environmental stress. Environ Health Perspect 1994;102:5–12. 10.1289/ehp.94102s105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schieber M, Chandel NS. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Biol 2014;24:R453–62. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madamanchi NR, Vendrov A, Runge MS. Oxidative stress and vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:29–38. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000150649.39934.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blé-Castillo JL, Rodríguez-Hernández A, Miranda-Zamora R, et al. Arthrospira maxima prevents the acute fatty liver induced by the administration of simvastatin, ethanol and a hypercholesterolemic diet to mice. Life Sci 2002;70:2665–73. 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)01512-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1279–90. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosseini SM, Khosravi-Darani K, Mozafari MR. Nutritional and medical applications of spirulina microalgae. Mini Rev Med Chem 2013;13:1231–7. 10.2174/1389557511313080009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamorro G, Salazar M, Favila L, et al. [Pharmacology and toxicology of Spirulina alga]. Rev Invest Clin 1996;48:389–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwata K, Inayama T, Kato T. Effects of spirulina platensis on plasma lipoprotein lipase activity in fructose-induced hyperlipidemic rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol 1990;36:165–71. 10.3177/jnsv.36.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riss J, Décordé K, Sutra T, et al. Phycobiliprotein C-phycocyanin from spirulina platensis is powerfully responsible for reducing oxidative stress and NADPH oxidase expression induced by an atherogenic diet in hamsters. J Agric Food Chem 2007;55:7962–7. 10.1021/jf070529g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torres-Duran PV, Ferreira-Hermosillo A, Juarez-Oropeza MA. Antihyperlipemic and antihypertensive effects of spirulina maxima in an open sample of Mexican population: a preliminary report. Lipids Health Dis 2007;6:33. 10.1186/1476-511X-6-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plaza Pérez I, Villar Álvarez F, Mata López P, et al. Control de la colesterolemia en españa, 2000. un instrumento para la prevención cardiovascular. Rev Esp Cardiol 2000;53:815–37. 10.1016/S0300-8932(00)75163-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher-Wellman K, Bloomer RJ. Acute exercise and oxidative stress: a 30 year history. Dyn Med 2009;8:1. 10.1186/1476-5918-8-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morillas-Ruiz JM, Villegas García JA, López FJ, et al. Effects of polyphenolic antioxidants on exercise-induced oxidative stress. Clin Nutr 2006;25:444–53. 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aoi W, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T. Role of oxidative stress in impaired insulin signaling associated with exercise-induced muscle damage. Free Radic Biol Med 2013;65:1265–72. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomez-Cabrera MC, Domenech E, Viña J. Moderate exercise is an antioxidant: upregulation of antioxidant genes by training. Free Radic Biol Med 2008;44:126–31. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savini I, Catani MV, Evangelista D, et al. Obesity-associated oxidative stress: strategies finalized to improve redox state. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:10497–538. 10.3390/ijms140510497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gammone MA, Gemello E, Riccioni G, et al. Marine bioactives and potential application in sports. Mar Drugs 2014;12:2357–82. 10.3390/md12052357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gammone MA, D'Orazio N. Anti-obesity activity of the marine carotenoid fucoxanthin. Mar Drugs 2015;13:2196–214. 10.3390/md13042196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Upasani CD, Khera A, Balaraman R. Effect of lead with vitamin E, C, or spirulina on malondialdehyde, conjugated dienes and hydroperoxides in rats. Indian J Exp Biol 2001;39:70–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagaoka S, Shimizu K, Kaneko H, et al. A novel protein C-phycocyanin plays a crucial role in the hypocholesterolemic action of Spirulina platensis concentrate in rats. J Nutr 2005;135:2425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thaakur SR, Jyothi B. Effect of spirulina maxima on the haloperidol induced tardive dyskinesia and oxidative stress in rats. J Neural Transm 2007;114:1217–25. 10.1007/s00702-007-0744-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart A, Marfell-Jones M, Olds T, et al. International standards for anthropometric assessment. Lower Hutt, New Zealand: ISAK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao TK, Van de Water J, Gershwin ME. Effects of a spirulina-based dietary supplement on cytokine production from allergic rhinitis patients. J Med Food 2005;8:27–30. 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiménez-Osorio AS, Picazo A, González-Reyes S, et al. Nrf2 and redox status in prediabetic and diabetic patients. Int J Mol Sci 2014;15:20290–305. 10.3390/ijms151120290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koren E, Kohen R, Ginsburg I. Polyphenols enhance total oxidant-scavenging capacities of human blood by binding to red blood cells. Exp Biol Med 2010;235:689–99. 10.1258/ebm.2010.009370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prior RL, Hoang H, Gu L, et al. Assays for hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidant capacity (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC(FL))) of plasma and other biological and food samples. J Agric Food Chem 2003;51:3273–9. 10.1021/jf0262256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pérez-Herrera N, May-Pech C, Hernández-Ochoa I, et al. PON1Q192R polymorphism is associated with lipid profile in Mexican men with mayan ascendancy. Exp Mol Pathol 2008;85:129–34. 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banach M, Stulc T, Dent R, et al. Statin non-adherence and residual cardiovascular risk: there is need for substantial improvement. Int J Cardiol 2016;225:184–96. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.09.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheong SH, Kim MY, Sok DE, et al. Spirulina prevents atherosclerosis by reducing hypercholesterolemia in rabbits fed a high-cholesterol diet. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol 2010;56:34–40. 10.3177/jnsv.56.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moura LP, Puga GM, Beck WR, et al. Exercise and spirulina control non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis and lipid profile in diabetic Wistar rats. Lipids Health Dis 2011;10:77. 10.1186/1476-511X-10-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ugwuja E, Ogbonna N, Nwibo A, et al. Overweight and obesity, lipid profile and atherogenic indices among civil servants in Abakaliki, South Eastern Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2013;3:13–18. 10.4103/2141-9248.109462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fenster CP, Weinsier RL, Darley-Usmar VM, et al. Obesity, aerobic exercise, and vascular disease: the role of oxidant stress. Obes Res 2002;10:964–8. 10.1038/oby.2002.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serban MC, Sahebkar A, Dragan S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of Spirulina supplementation on plasma lipid concentrations. Clin Nutr 2016;35:842–51. 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hernández-Lepe MA, Wall-Medrano A, Juárez-Oropeza MA, et al. Spirulina y su efecto hipolipemiante y antioxidante en humanos: una revisión sistemática. Nutr Hosp 2015;32:494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013744supp001.pdf (89.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013744supp002.jpg (276.1KB, jpg)