Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the diagnostic performance of a UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence-recommended automatic oscillometric blood pressure (BP) measurement device incorporated with an atrial fibrillation (AF) detection algorithm (Microlife WatchBP Home A) for real-world AF screening in a primary healthcare setting.

Setting

Primary healthcare setting in Hong Kong.

Interventions

This was a prospective AF screening study carried out between 1 September 2014 and 14 January 2015. The Microlife device was evaluated for AF detection and compared with a reference standard of lead-I ECG.

Primary outcome measures

Diagnostic performance of Microlife for AF detection.

Results

5969 patients (mean age: 67.2±11.0 years; 53.9% female) were recruited. The mean CHA2DS2-VASc (C: congestive heart failure [1 point]; H: hypertension [1 point]; A2: age 65-74 years [1 point] and age ≥75 years [2 points]; D: diabetes mellitus [1 point]; S: prior stroke or transient ischemic attack [2 points]; VA: vascular disease [1 point]; and Sc: sex category [female] [1 point])score was 2.8±1.3. AF was diagnosed in 72 patients (1.21%) and confirmed by a 12-lead ECG. The Microlife device correctly identified AF in 58 patients and produced 79 false-positives. The corresponding sensitivity and specificity for AF detection were 80.6% (95% CI 69.5 to 88.9) and 98.7% (95% CI 98.3 to 98.9), respectively. Among patients with a false-positive by the Microlife device, 30.4% had sinus rhythm, 35.4% had sinus arrhythmia and 29.1% exhibited premature atrial complexes. With the low prevalence of AF in this population, the positive and negative predictive values of Microlife device for AF detection were 42.4% (95% CI 34.0 to 51.2) and 99.8% (95% CI 99.6 to 99.9), respectively. The overall diagnostic performance of Microlife device to detect AF as determined by area under the curves was 0.90 (95% CI 0.89 to 0.90).

Conclusions

In the primary care setting, Microlife WatchBP Home was an effective means to screen for AF, with a reasonable sensitivity of 80.6% and a high negative predictive value of 99.8%, in addition to its routine function of BP measurement. In a younger patient population aged <65 years with a lower prevalence of AF, Microlife WatchBP Home A demonstrated a similar diagnostic accuracy.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, microlife, screening

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Prospective study evaluating the diagnostic value for atrial fibrillation (AF) of a commercially available UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)-recommended device: Microlife.

Large study population in a primary care setting.

Study results support the use of Microlife device can be extended to <65 years old for AF detection, extending the UK NICE recommendations for AF screening.

Due to the primary healthcare setting, 12-lead ECG is not feasible in every recruited patient; thus, single-lead-I ECG tracing was used as reference instead to provide rhythm diagnosis.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) has emerged as a global epidemic with a progressive increase in incidence, prevalence, and consequent stroke and mortality.1

Although AF-related stroke and mortality are highly preventable with the use of long-term oral anticoagulants, up to 25% of patients with AF-related stroke have AF diagnosed only at the time of stroke,2–4 precluding any form of primary preventive measure. As a result, diagnosing AF prior to stroke occurrence is now recognised as a priority. The European Society of Cardiology recommends opportunistic screening for AF (pulse palpitation, followed by standard ECG if irregular pulse detected) in patients aged 65 years or older.5 6

In addition to advanced age and diabetes mellitus, hypertension is another important risk factor for AF,7 accounting for 14% of the AF burden in both men and women.8 Hypertension contributes more AF cases than any other risk factor because of its high prevalence (~1 billion individuals worldwide). Different risk factors had various impacts on the development of incident AF; for instance, hypertension had an OR of 1.8 on 10-year risk of AF while advanced age and diabetes mellitus had ORs of 2.3 and 1.1, respectively.

Recently, an automatic oscillometric blood pressure (BP) measurement device with an incorporated specific algorithm to detect AF (Microlife WatchBP Home A; Microlife USA, Dunedin, Florida, USA) has been recommended by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to screen for AF during routine office BP measurement in primary care patients aged 65 years or older.9 The ability to detect AF in the Microlife device is based on measuring the time interval between successive R-R cycles and computing the ratio of the SD of these time intervals to the mean R-R intervals. If this irregularity index generated is above certain cut-off, this would be interpreted as positive for AF by the device.7

Although the diagnostic performance of the device for AF detection has been previously investigated,7–12 these studies have been limited by their relatively small sample size, typically less than 1000 participants.7–12 The total number of participants was around 2000 only. More importantly, most studies were carried out in a high-risk population, such as a general cardiology clinic7 9 11 or in patients with recent stroke.12 The generalisability to a primary care setting, the target environment for mass AF screening, remains questionable. In addition, the diagnostic procedure has evolved throughout these studies; for instance, the number of readings used for diagnosis of AF increased from one in the initial study11 to three in the latest study, and has substantially improved the diagnostic performance.12 Therefore, the performance of the Microlife WatchBP Home A for AF screening using the current diagnostic procedure in a real-world mass AF screening setting remains unclear. The primary aim of this study was to assess the diagnostic performance of the Microlife WatchBP Home A for AF screening.

Methods

Study design

This prospective screening study was coordinated by the University of Hong Kong and the Department of Family Medicine and Primary Healthcare Service, Hong Kong East Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong. The study protocol was approved by the local institutional review board. Patients were recruited from the Violet Peel General Outpatient Clinic in Hong Kong from September 2014 to January 2015. Patients were eligible if they had a history of hypertension and/or diabetes mellitus, or were ≥65 years of age. Patients with a pacemaker or implantable defibrillator were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Screening procedure

A bipolar lead-I ECG recording was first obtained from all patients using an AliveCor Heart Monitor (AliveCor, San Francisco, California, USA). The AliveCor Heart Monitor is Food and Drug Administration-cleared, Conformité Européenne-marked and clinically validated for the recording of single-channel lead-I ECGs.13 14 For each patient, a single-lead ECG tracing was acquired for 30 s with placement of two or more fingers from each hand on the device electrodes. The ECG recordings were transmitted to an iPad Mini (Apple, Cupertino, California, USA) installed with the AliveECG application (V.2.1.1), and were reviewed by two independent cardiologists who were blinded to the Microlife WatchBP Home AF classifications to provide a reference diagnosis using standard criteria.15 When a diagnosis of AF was made, a full 12-lead ECG was performed. Immediately following completion of the ECG recording, three BP measurements were taken using the automatic oscillometric BP monitor (the Microlife WatchBP Home A) with AF detection algorithm. The ‘Afib’ icon flashed when AF was detected.

Statistical analysis

Continuous and discrete variables are expressed as mean±SD and percentages, respectively. Sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratio and predictive value for AF diagnosis were calculated as simple proportions with corresponding 95% CI for the Microlife WatchBP Home classifications for AF detection. The diagnostic performance for AF detection was further assessed using the c-statistic (area under the curve). The c-statistic for receiver operating characteristic curve was calculated using Analyse-It for Excel with the Delong-Delong comparison for c-statistic. The c-statistic integrates measures of sensitivity and specificity of the range of a variable. Ideal prediction yields a c-statistic of 1.00, whereas a value of <0.5 indicates that the prediction is no better than chance. Calculations were performed using SPSS software (V.21.0) and MedCal (V.13.1.2).

Results

Between 1 September 2014 and 14 January 2015, 6075 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the AF screening study, of whom 106 declined (1.7%). As a result, 5969 patients were included in this study (figure 1). Table 1 summarises their characteristics. The mean age was 67.2±11.0 years and 2751 patients (46.1%) were male. Hypertension was present in 4948 patients (82.9%) and diabetes mellitus in 2742 (45.9%). Coronary artery disease was present in 313 patients (5.2%) and 271 (4.5%) had a history of ischaemic stroke. The mean CHA2DS2-VASc score (C: congestive heart failure [1 point]; H: hypertension [1 point]; A2: age 65-74 years [1 point] and age ≥75 years [2 points]; D: diabetes mellitus [1 point]; S: prior stroke or transient ischemic attack [2 points]; VA: vascular disease [1 point]; and Sc: sex category [female] [1 point]) was 2.8±1.3.

Figure 1.

Study enrolment and flow.

Table 1.

Demographics of study population

| Characteristics | Number (%) (n=5969) |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 67.2±11.0 |

| Male | 2751 (46.1) |

| Hypertension | 4948 (82.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2742 (45.9) |

| Coronary artery disease | 313 (5.2) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 46 (0.8) |

| Heart failure | 54 (0.9) |

| Previous stroke | 271 (4.5) |

| Previous intracranial haemorrhage | 35 (0.6) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 2.8±1.3 |

CHA2DS2-VASc score (C: congestive heart failure [1 point]; H: hypertension [1 point]; A2: age 65-74 years [1 point] and age ≥75 years [2 points]; D: diabetes mellitus [1 point]; S: prior stroke or transient ischemic attack [2 points]; VA: vascular disease [1 point]; and Sc: sex category [female] [1 point])

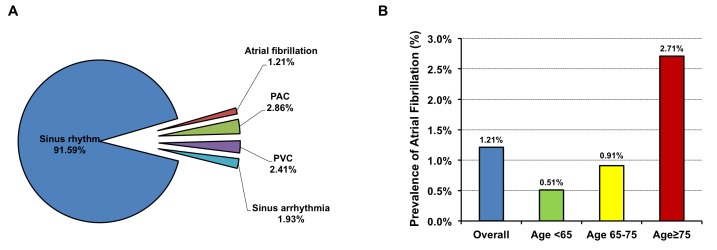

Of these 5969 patients, 5467 (91.59%) had sinus rhythm based on interpretation by two cardiologists of the single-lead ECG recording (figure 2A). AF was diagnosed in 72 patients (1.21%) and confirmed by a standard 12-lead ECG. Other abnormal non-AF rhythms detected in the study population included premature atrial contractions (n=171, 2.86%), premature ventricular contractions (n=144, 2.41%) and sinus arrhythmias (n=115, 1.93%). The prevalence of AF increased with increasing age from 0.51% among those aged <65 years, to 0.91% among those aged 65–74 years and 2.71% among those aged ≥75 years (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Rhythm diagnoses of the study population based on interpretation by two independent cardiologists of a 30 s bipolar lead-I ECG. (B) Prevalence of AF categorised into different age groups. AF, atrial fibrillation; PAC, premature atrial complex; PVC, premature ventricular complex

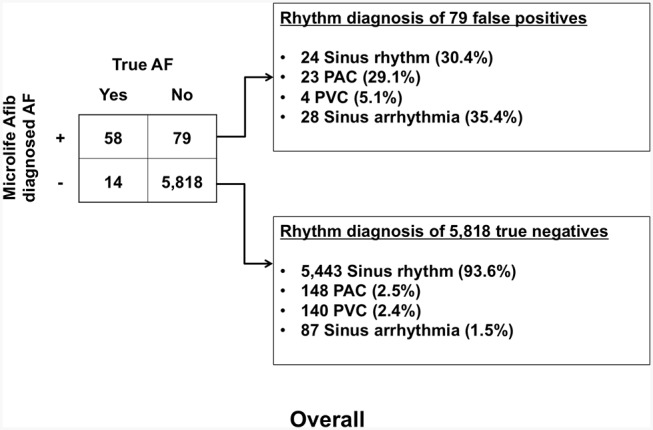

The Microlife WatchBP Home A correctly identified the presence of AF in 58 out of 72 patients with AF and produced 79 false-positive results (figure 3). The corresponding sensitivity of the Microlife WatchBP Home A to detect AF was 80.6% (95% CI 69.5 to 88.9). The Microlife WatchBP Home A produced a false-positive result for AF in 79 of 5897 non-AF patients, with a corresponding specificity of 98.7% (95% CI 98.3 to 98.9). Among these 79 patients, 24 had sinus rhythm (30.4%), 28 had sinus arrhythmia (35.4%), 23 had premature atrial contractions (29.1%) and 4 had premature ventricular contractions (5.1%) (figure 3). Nonetheless the specificity of the Microlife WatchBP Home A for AF detection remained high in these patients: 99.6% in patients with sinus rhythm, 97.2% in patients with premature ventricular contractions, 86.5% in patients with premature atrial contractions and 75.7% in patients with sinus arrhythmia. Given the relatively low prevalence of AF (1.21%) in this population, the positive and negative predictive values of the Microlife WatchBP Home A to detect AF were 42.4% (95% CI 34.0 to 51.2) and 99.8% (95% CI 99.6 to 99.9), respectively. The positive likelihood ratio and the negative likelihood ratio of the Microlife WatchBP Home A were 60.1 (95% CI 47.0 to 77.0) and 0.2 (95% CI 0.1 to 0.3), respectively. The overall diagnostic performance of the Microlife WatchBP Home A to detect AF as determined by area under the curves was 0.90 (95% CI 0.89 to 0.90).

Figure 3.

Contingency table for atrial fibrillation detection and rhythm diagnoses of an automatic oscillometric blood pressure measurement device incorporated with a specific algorithm for AF detection (Microlife WatchBP Home A). AF, atrial fibrillation; PAC, premature atrial complex; PVC, premature ventricular complex.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest screening study for AF using the UK NICE guideline-recommended Microlife WatchBP Home A automatic BP monitoring machine. In this study, the diagnostic performance of Microlife WatchBP Home A was compared with a reference standard of single-lead-I ECG. First, our results demonstrate that in the primary care setting where the prevalence of AF is relatively low, the Microlife WatchBP Home A machine detected AF with a reasonable sensitivity of 80.6%, high specificity of 98.7% and negative predictive value of 99.8%. Second, the device detected AF with high diagnostic accuracy as determined by area under the curves of 0.9, when compared with reference single-lead-I ECG. Third, the device effectively detected AF in patients younger than 65 years — not the usual target population for AF screening. Finally, the diagnostic performance of the device, in terms of sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values, did not differ across different age groups, with a mean age of patients in this study of 67.2±11.0 years.

It is well established that AF is associated with a fivefold increased risk of ischaemic stroke.16 With effective anticoagulation by warfarin, such risk can be reduced by 64%.17 Nonetheless in the absence of a firm diagnosis of AF, for instance in patients who are asymptomatic, anticoagulation therapy cannot be commenced. Underlying AF is newly diagnosed in up to 25% of patients with ischaemic stroke.2–4 Thus, AF screening was recommended by the European Society of Cardiology in those aged 65 years or older to diagnose AF in this high-risk population,5 where advanced age is one of the important underlying risk factors.18 To achieve effective AF screening, the availability of a reliable easy-to-use screening tool is of paramount importance. A conventional 12-lead ECG records cardiac rhythm for 10 s and is the gold standard for diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmia. Nonetheless although a 12-lead ECG can be employed as a screening tool for AF,19 its cumbersome and time-consuming nature makes it less appealing, particularly on a large scale. As a result, there has been a recent surge in the availability of various easy-to-use devices.

The automated oscillometric BP monitoring machine — Microlife WatchBP Home A — can distinguish AF from normal sinus rhythm based on the detection of pulse irregularities during BP measurement.7 9–11 By measuring the time interval between successive R-R cycles and calculating the ratio of the SD of these time intervals to the mean R-R interval, an irregularity index is generated. Previous study confirmed that an irregularity index with a cut-off of >0.06 corresponds to AF with high sensitivity and specificity.7 Theoretically, lowering the cut-off irregularity index might increase sensitivity for AF detection, although at the cost of lower specificity. In addition, the Microlife WatchBP Home A device used in this study automatically measured BP three times: this further improved the diagnostic accuracy for pulse irregularities or AF. Of note, the programmed AF detector in Microlife WatchBP Home A device differs from all other arrhythmia detectors incorporated in many automated BP monitors in that it is specific for AF.7 9 10 20–23 Arrhythmia detectors installed in other automated BP monitors provide only a warning that the BP recorded may be inaccurate due to the possible presence of arrhythmia, rather than specifically diagnosing AF.24

Other devices, such as the AliveCor Heart Monitor, which is equipped with automatic algorithms for interpreting a lead-I ECG tracing, have also been tested in previous studies,14 25 including the recently published STROKESTOP study on Caucasian population and the head-to-head comparison study in the primary care setting in Chinese population.26 27 This study used the Microlife WatchBP Home A device to detect AF, but it was only validated in a population aged 65 years or above, the target population for AF screening. One of the important findings in this study was that the diagnostic performance of Microlife WatchBP Home A machine in a younger patient population, which was characterised by a lower prevalence of AF and other arrhythmias including premature atrial complex, was not negatively affected. Current guidelines5 28 promote AF screening only in those aged ≥65 years because of the lack of clinical evidence and possibly higher prevalence of sinus arrhythmia and thus false-positive results in younger subjects. The current study provides evidence that the Microlife WatchBP Home A machine achieves comparable diagnostic accuracy in those aged <65 and those ≥65. This device is also the first to be validated for AF screening in younger patients aged <65, potentially extending the indication of UK NICE guideline for the Microlife WatchBP Home A machine. In this study, detection of AF during automated BP measurement was feasible in the primary care setting and appeared to be superior to routine pulse palpation in terms of diagnostic accuracy for AF, hence facilitating AF screening in high-risk patients in the primary care setting. Importantly, the incidence of AF in the general population is around 1%–2% depending on ethnicity, and is usually lower in Chinese population.29 30 Therefore, in a population with relatively low incidence of AF, the good sensitivity and high negative predictive value of the device for AF screening would be invaluable and ideal for a screening tool.

One of the potential drawbacks of the Microlife WatchBP Home A machine is a false-positive result that necessitates subsequent confirmation by an ECG for an accurate arrhythmia diagnosis. This may be anxiety-promoting in patients who are found to have AF. Theoretically, repetition of measurements with the device should improve diagnostic accuracy. This also applies to patients with paroxysmal AF: repeated measurement might enhance the sensitivity of the test, as demonstrated in the recent study using a smartphone-based device for AF screening — the rate of AF detection increased with longer duration of measurement.26 It also helps to identify AF in those at-risk patients who regularly perform home BP monitoring, for instance, elderly patients with hypertension who are usually asymptomatic despite the presence of underlying AF. From the 79 patients with a false-positive Microlife test result, the presence of premature atrial complex or sinus arrhythmia each accounted for around one-third of patients. Given the low false-positive rate of 1.3% and high specificity, the device is regarded as a good screening tool.

Of note, the sensitivity of the device in this study is 80.6% (95% CI 69.5 to 88.9), which means there is probability that 2–3 out of 10 patients with underlying AF could be missed by this screening tool. Physicians using this device to screen for AF should be well aware of this potential drawback and should not solely rely on this device and hence producing a false sense of security. The possible ways to improve the sensitivity include repeated measurements with Microlife device at intervals and combining the use of other screening tools in AF detection.

An advantage of the Microlife WatchBP Home A machine as an AF screening tool is its ease of use and less time-consuming nature compared with performing a routine 12-lead ECG in every patient who attends a primary care clinic. BP is measured in most patients as a matter of routine during follow-up with a family physician so it is advantageous to simultaneously be able to detect AF. This study demonstrated that the Microlife WatchBP Home A machine is an invaluable means of screening for AF in an at-risk population in the primary care setting with a relatively lower prevalence of AF, including patients aged <65 years.

Study limitation

A formal 12-lead ECG was not recorded in every participant. Instead, two cardiologists independently over-read a single-lead ECG of each patient and provided a diagnosis. This was necessary given the time and cost constraints inherent in dealing with a large number of patients. Nonetheless all patients identified by the cardiologists to have AF underwent a follow-up 12-lead ECG for further confirmation of the diagnosis.

Conclusion

In the primary care setting with an AF prevalence of 1.21%, Microlife WatchBP Home A was shown to be an effective screening tool for AF with a reasonable sensitivity of 80.6% and high negative predictive value of 99.8%, as well as provide a routine function of BP measurement. Diagnostic accuracy of the Microlife WatchBP Home A in a younger patient population aged <65 years and a lower prevalence of AF achieved a similar diagnostic accuracy compared with its use in an older population, thus potentially extending the NICE guideline indication as an AF screening tool to a younger at-risk population.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Contributions to the conception or design of the work: CPH, WCK, CDW, CWS.

Contributions to the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work: all authors.

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: CPH, WCK, CWS.

Final approval of the version to be published: all authors.

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: all authors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee, Hong Kong East Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, et al. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a global burden of disease 2010 Study. Circulation 2014;129:837–47. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf PA, Kannel WB, McGee DL, et al. Duration of atrial fibrillation and imminence of stroke: the Framingham study. Stroke 1983;14:664–7. 10.1161/01.STR.14.5.664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siu CW, Lip GY, Lam KF, et al. Risk of stroke and intracranial hemorrhage in 9727 chinese with atrial fibrillation in Hong Kong. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:1401–8. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lindgren A, et al. High prevalence of atrial fibrillation among patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke 2014;45:2599–605. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the european Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J 20122012;33:2719–47. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzmaurice DA, Hobbs FD, Jowett S, et al. Screening versus routine practice in detection of atrial fibrillation in patients aged 65 or over: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007;335:383. 10.1136/bmj.39280.660567.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiesel J, Fitzig L, Herschman Y, et al. Detection of atrial fibrillation using a modified microlife blood pressure monitor. Am J Hypertens 2009;22:848–52. 10.1038/ajh.2009.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearley K, Selwood M, Van den Bruel A, et al. Triage tests for identifying atrial fibrillation in primary care: a diagnostic accuracy study comparing single-lead ECG and modified BP monitors. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004565 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiesel J, Arbesfeld B, Schechter D. Comparison of the microlife blood pressure monitor with the Omron blood pressure monitor for detecting atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2014;114:1046–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stergiou GS, Karpettas N, Protogerou A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a home blood pressure monitor to detect atrial fibrillation. J Hum Hypertens 2009;23:654–8. 10.1038/jhh.2009.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiesel J, Wiesel D, Suri R, et al. The use of a modified sphygmomanometer to detect atrial fibrillation in outpatients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2004;27:639–43. 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00499.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandolfo C, Balestrino M, Bruno C, et al. Validation of a simple method for atrial fibrillation screening in patients with stroke. Neurol Sci 2015;36:1675–8. 10.1007/s10072-015-2231-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garabelli P, Albert D, Reynolds D. Accuracy and novelty of an inexpensive iPhone-based event recorder. Heart Rhythm Scientific Sessions 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowres N, Neubeck L, Salkeld G, et al. Feasibility and cost-effectiveness of stroke prevention through community screening for atrial fibrillation using iPhone ECG in pharmacies. the SEARCH-AF study. Thromb Haemost 2014;111:295–304. 10.1160/TH14-03-0231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.January CT, Calkins H, Faha F, et al. AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the management of patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2014;2014:000–00. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lip GY, Tse HF, Lane DA. Atrial fibrillation. Lancet 2012;379:648–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61514-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:857–67. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnabel RB, Sullivan LM, Levy D, et al. Development of a risk score for atrial fibrillation (Framingham Heart Study): a community-based cohort study. Lancet 2009;373:739–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60443-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobbs FD, Fitzmaurice DA, Mant J, et al. A randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness study of systematic screening (targeted and total population screening) versus routine practice for the detection of atrial fibrillation in people aged 65 and over. the SAFE study. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:iii-iv, ix-x, 1-74. 10.3310/hta9400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marazzi G, Iellamo F, Volterrani M, et al. Comparison of Microlife BP A200 Plus and Omron M6 blood pressure monitors to detect atrial fibrillation in hypertensive patients. Adv Ther 2012;29:64–70. 10.1007/s12325-011-0087-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verberk WJ, de Leeuw PW. Accuracy of oscillometric blood pressure monitors for the detection of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Expert Rev Med Devices 2012;9:635–40. 10.1586/erd.12.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willits I, Keltie K, Craig J, et al. WatchBP Home A for opportunistically detecting atrial fibrillation during diagnosis and monitoring of hypertension: a NICE Medical Technology Guidance. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2014;12:255–65. 10.1007/s40258-014-0096-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verberk WJ, Omboni S, Kollias A, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation with automated blood pressure measurement: research evidence and practice recommendations. Int J Cardiol 2016;203:465–73. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kearley K, Selwood M, Van den Bruel A, et al. Triage tests for identifying atrial fibrillation in primary care: a diagnostic accuracy study comparing single-lead ECG and modified BP monitors. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004565. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orchard J, Freedman SB, Lowres N, et al. iPhone ECG screening by practice nurses and receptionists for atrial fibrillation in general practice: the GP-SEARCH qualitative pilot study. Aust Fam Physician 2014;43:315–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svennberg E, Engdahl J, Al-Khalili F, et al. Mass screening for Untreated Atrial Fibrillation: the STROKESTOP study. Circulation 2015;131:2176–84. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan PH, Wong CK, Pun L, et al. Head-to-Head comparison of the aliveCor heart monitor and microlife watchBP office AFIB for atrial fibrillation screening in a primary care setting. Circulation 2017;135:110–2. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones C, Pollit V, Fitzmaurice D, et al. The management of atrial fibrillation: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2014;348:g3655. 10.1136/bmj.g3655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and risk factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 2001;285:2370–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Z, Hu D. An epidemiological study on the prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the chinese population of mainland China. J Epidemiol 2008;18:209–16. 10.2188/jea.JE2008021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.