Abstract

Objective

To determine whether the presence of hypercapnia on admission in adult patients admitted to a university-based hospital in Karachi, Pakistan with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) correlates with an increased length of hospital stay and severity compared with no hypercapnia on admission.

Study design

A prospective observational study.

Settings

Tertiary care hospital in Karachi, Pakistan.

Methods

Patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. The severity of pneumonia was assessed by CURB-65 and PSI scores. An arterial blood gas analysis was obtained within 24 hours of admission. Based on arterial PaCO2 levels, patients were divided into three groups: hypocapnic (PaCO2 <35 mm Hg), hypercapnic (PaCO2 >45 mm Hg) and normocapnic (PaCO2 <35–45 mm Hg).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the association of hypercapnia on admission with mean length of hospital stay. Secondary outcomes were the need for mechanical ventilation, ICU admission and in-hospital mortality.

Results

A total of 295 patients of mean age 60.20±17.0 years (157 (53.22%) men) were enrolled over a 1-year period. Hypocapnia was found in 181 (61.35%) and hypercapnia in 57 (19.32%) patients. Hypercapnic patients had a longer hospital stay (mean 9.27±7.57 days), increased requirement for non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) on admission (n=45 (78.94%)) and longer mean time to clinical stability (4.39±2.0 days) compared with the other groups. Overall mortality was 41 (13.89%), but there was no statistically significant difference in mortality (p=0.35) and ICU admission (p=0.37) between the three groups. On multivariable analysis, increased length of hospital stay was associated with NIMV use, ICU admission, hypercapnia and normocapnia.

Conclusion

Hypercapnia on admission is associated with severity of CAP, longer time to clinical stability, increased length of hospital stay and need for NIMV. It should be considered as an important criterion to label the severity of the illness and also a determinant of patients who will require a higher level of hospital care. However, further validation is required.

Keywords: Pneumonia, Respiratory failure, Hypercapnia, Hypocapnia

Strengths and limitations of the study.

This is the first study from Pakistan to assess the association of hypercapnia with increased length of stay (LOS) and severity in adult patients admitted with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) as very limited data are available from this part of the world.

Time to clinical stability and LOS, important predictors of CAP, were studied in correlation with PaCO2 levels.

This is an observational study from a single centre with a limited sample size.

It is an observational study which may be influenced by season, time of admission and steroid use.

We did not study the underlying cause of death and complications which developed during hospital stay in these patients.

Introduction

Severe community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a common infectious condition that requires hospitalisation. It is a substantial cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 Limited data are available from Pakistan on the incidence of CAP, while studies from the USA and Europe have shown an incidence rate of 1600/100 000 population, including 250/100 000 requiring hospitalisation.2 Approximately 10–20% of patients with CAP require intensive care unit (ICU) admission.3 Mortality may be as high as 58% if mechanical ventilation and/or ICU admission is needed.4

Most patients with CAP improve within 3 days of hospitalisation with appropriate antibiotic therapy. Length of hospital stay (LOS) is influenced by comorbid conditions, disease severity on presentation5 and the time required for clinical stability (TCS). The TCS varies from 3 to 7 days; patients with more severe CAP on presentation usually require more days to achieve clinical stability.6 In a study by Menendez et al7 it was found that hypoxaemia, anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia and other complications appearing within 72 hours of admission were associated with prolonged hospitalisation. In another study, longer TCS was associated with poor clinical outcomes and ICU stay.8 However, none of these factors correlated with the PaCO2 levels.

Corticosteroids have been analysed in various CAP studies and meta-analysis found that the adjunct steroid therapy in severe CAP reduces the overall LOS but does not alter in-hospital mortality and length of ICU stay.9 Prednisolone treatment for 7 days in hospitalised patients with CAP was found to have shortened TCS without an increase in complications.10 A short steroid course decreases the risk of treatment failure and reduces radiographic progression of pulmonary infiltrates within 3–5 days in severe CAP.11

Patients with severe CAP usually present with acute respiratory failure, which is the the most common cause of death in CAP.12 Various prognostic tools have been used to predict the severity of pneumonia. Hypoxaemic respiratory failure is a well-known prognostic marker in different severity of illness scores.12 13 Relatively newer severity scores, such as SCAP14 and SMART-COP,13have included low arterial pH as a criterion, but PaCO2 has not been used as a predictive variable in any such scores. Hypercapnia is considered an indicator of muscle fatigue and impending cardiopulmonary arrest. It causes various physiological effects on the human body, independent of extracellular and intracellular acidosis.15 16

The aim of this study was to determine whether hypercapnia (defined as a PaCO2 >45 mm Hg on arterial blood gas (ABG) measurement) on admission has any association with increased LOS and severity in patients with CAP in comparison with those without hypercapnia on admission.

Methods

Setting

This was an observational prospective study conducted on patients with a diagnosis of CAP from January to December 2014 at Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. The hospital ethics review committee approved the research protocol.

Patients who fulfilled the admission criteria for CAP as per British Thoracic Society guidelines were admitted to the study.17 Severity was assessed using the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI)18 and CURB-65 score at the time of admission. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age ≥18 years; (2) ABG analysis within 24 hours of admission; (3) fulfilment of CAP diagnostic criteria based on (a) new infiltrates observed on chest X-ray and/or CT scan chest, (b) one major criterion (axillary temperature >37.8°C, cough or expectoration) or at least two minor criteria (pleuritic chest pain, dyspnoea, leucocytosis, altered mental status or lung consolidation by clinical examination). We excluded patients who had a history of hospitalisation in the previous month or were transferred from another hospital, patients with do not resuscitate or comfort care status and those not meeting the criteria for CAP.

The arterial PaCO2 level was assessed by the Cobas b221 blood gas system (Roche Diagnostics USA) which includes pH measurement by electrode ion-selective galvanometer and PaCO2, PaO2 measurement by electrode ion-selective membrane. ABG analyses were done within 24 hours of admission. The patients were divided into three groups based on the level of PaCO2 in the arterial blood: (1) hypocapnia (PaCO2 level <35 mm Hg); (2) hypercapnia (PaCO2 >45 mm Hg); and (3) normocapnia (PaCO2 level 35–45 mm Hg).

Non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) was used for all those who met one or more eligibility criteria, experienced acute respiratory distress at rest, had a respiratory rate of >30 breaths/min and/or excessive use of accessory respiratory muscles or paradoxical abdominal motion; ABG parameters which included PaO2 <60 mm Hg while receiving a high level of fraction of inspired oxygen and/or hypercapnia (PaCO2 >45 mm Hg) with respiratory acidosis (pH <7.35). The methodology used was as described in previous literature.19 NIMV was used in the spontaneous mode with the assistance of pulmonary fellows/residents and trained nurses.

In the majority of patients NIMV was started in the emergency room but, if the patient was too sick on arrival or failed a NIMV trial, then intubation was done immediately. Patients were intubated based on the clinical judgement of the physician and/or based on previously reported parameters.19 20 NIMV therapy was initiated with an inspiratory airway pressure of 10 cm H2O and an expiratory airway pressure of 5 cm H2O. This was optimised using continuous pulse oximetry readings, ABG measurements (at 1 hour and periodically thereafter as clinically indicated) and patient comfort assessment. The discontinuation of NIMV was based on clinical judgement and ABG values.

Patients were excluded from NIMV if they had any of the following: (1) severe haemodynamic instability; (2) emergency need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation; (3) home mechanical ventilation; (4) active vomiting; (5) inability to expectorate; (6) neuromuscular weakness; (7) contraindications to the use of the mask such as tracheostomy, facial trauma and deformities.

The primary outcome was the association between hypercapnia on admission and mean LOS; secondary outcomes were need for mechanical ventilation, ICU admission and in-hospital mortality. Medical management was similar in all three groups with adherence to guidelines.17 Oxygen was administered to achieve a level of arterial oxygen saturation of >90% by pulse oximetry.

Data source

We used a non-probability consecutive sampling technique for patient recruitment by assuming LOS is higher among hypercapnic patients by 35%,21 with a 95% confidence level, 80% power and odds ratio of 1.93, which required a sample of at least 285 patients.

All patients admitted with CAP who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. Informed written consent was obtained from the patients or the attendant next of kin. Data were collected on each patient’s demographics, age, sex, comorbid conditions, ABG values within the first 24 hours of admission, LOS, TCS, in-hospital mortality, need for NIMV and ICU admission/mechanical ventilation on a predesigned proforma. Patients were followed till discharge or death, if occurred during hospitalisation.

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) release 18.0, standard version (1989–02). A descriptive analysis of demographic features is presented as mean±SD for quantitative variables (ie, age, LOS and LOS in the hypocapnia, hypercapnia and normocapnia groups) and number (%) for qualitative variables (ie, gender, mortality, hypocapnia, hypercapnia and normopcania and mortality in hypocapnia, hypercapnia and normocapnia groups). A χ2 test was used to compare the mortality in the three groups and ANOVA was used for mean LOS in the three groups. Due to the skewed distribution of LOS, it was categorised for the main analysis. LOS was dichotomised into mean <7 days and >7 days. ORs and their 95% CIs were estimated using logistic regression with LOS as the outcome variable. Kaplan–Meier plot analysis was done to assess LOS among the three PaCO2 groups. All significant factors in the univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the multivariable logistic model. All p values were two-sided and p values ≤0.05 were taken as significant.

Results

A total of 295 patients were enrolled. The mean age was 60.20±17.0 years, 157 (53.22%) were male and 138 (46.77%) were female. The majority of the patients with CAP were hypocapnic (n=181 (61.35%)) while hypercapnia and normocapnia was found in 57 patients (19.32%) in each group. There was no statistically significant difference in age between the groups (p=0.18). Diabetes (n=25 (43.9%), p=0.03) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; n=11 (19.3%), p<0.001) were more common in the hypercapnic group while patients with normocapnia had ischaemic heart disease (IHD; n=18 (31.57%), p=0.04). In the hypercapnic group, 35 patients (61.40%) had pH <7.35 (p<0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in mean PaO2 between the three groups (p=0.37).

Hypercapnic patients had a higher CURB-65 score (3.14±1.28, p=0.004), PSI score (95.68±29.12, p=0.002), renal failure (n=42 (73.68%), p=0.01) and bilateral radiographic infiltrates (n=31 (54.4%), p=0.03) on presentation compared with the hypocapnic and normocapnic groups. The majority of patients with hypercapnia received systemic corticosteroids (n=42 (73.7%), p<0.001), required NIMV (n=50 (87.71%), p=0.03) and had longer TCS (4.39±2.0, p=0.03) compared with hypocapnic and normocapnic patients (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients admitted with community-acquired pneumonia

| Normocapnia (PaCO2 35–45 mm Hg) | Hypocapnia (PaCO2 <35 mm Hg) | Hypercapnia (PaCO2 >45 mm Hg) | p Value | |

| Total patients (n=295) |

57 (19.32%) | 181 (61.35%) | 57 (19.32%) | |

| Mean age (years) | 61.14±13.85 | 58.18±18.97 | 65.77±11.37 | 0.18 |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 18 (31.57%) | 108 (59.66%) | 31 (54.38%) | 0.08 |

| Women | 39 (68.42%) | 73 (40.33%) | 26 (45.61%) | |

| Season | ||||

| January to April | 24 (42.1%) | 53 (29.3%) | 34 (59.6%) | 0.001 |

| May to August | 14 (24.6%) | 57 (31.5%) | 8 (14%) | |

| September to December | 19 (33.3%) | 71 (39.2%) | 15 (26.3%) | |

| Comorbid Diabetes |

23 (40.35%) | 50 (27.62%) | 25 (43.9%) | 0.03 |

| IHD | 18 (31.57%) | 33 (18.23%) | 14 (24.6%) | 0.04 |

| HTN | 27 (47.4%) | 68 (37.6%) | 27 (47.4%) | 0.25 |

| COPD | 0 | 4 (2.2%) | 11 (19.3%) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 3 (5.3%) | 25 (13.8%) | 10 (17.5%) | 0.12 |

| pH | ||||

| <7.35 | 5 (8.7%) | 8 (4.4%) | 35 (61.40%) | <0.001 |

| >7.35 | 52 (91.22%) | 173 (95.58%) | 22 (38.59%) | |

| PaO2 level (mean) | 69.13±17.98 | 71.68±20.16 | 78.45±35 | 0.37 |

| PaCO2 level (mean) | 37.05±3.65 | 30.66±9.54 | 65.36±18.94 | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine | ||||

| <1 | 36 (63.15%) | 59 (32.59%) | 15 (26.31%) | 0.01 |

| >1 | 21 (36.84%) | 122 (67.40%) | 42 (73.68%) | |

| CURB65 (mean±SD) | 2.0±1.06 | 2.37±1.14 | 3.14±1.28 | 0.004 |

| PSI (mean±SD) | 66.36±32.4 | 72.39±29.46 | 95.68±29.12 | 0.002 |

| Chest X-ray infiltrates | ||||

| Unilateral | 35 (61.4%) | 118 (65.2%) | 26 (45.6%) | 0.03 |

| Bilateral | 22 (38.6%) | 63 (34.8%) | 31 (54.4%) | |

| Use of steroids (systemic) |

||||

| Yes | 27 (47.4%) | 73 (40.3%) | 42 (73.7%) | <0.001 |

| 30 (52.6%) | 108 (59.7%) | 15 (26.3%) | ||

| NIMV therapy | ||||

| ER | 15 (26.3%) | 112 (61.8%) | 50 (87.71%) | 0.03 |

| SCU | 15 (24.5%) | 94 (51.93%) | 45 (78.94%) | |

| ICU | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| NIMV failure in ER | 0 | 18 (9.9%) | 5 (8.7%) | |

| TCS (mean±SD), days |

2.76±2.1 | 3.17±1.99 | 4.39±2.0 | 0.03 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ER, emergency room; HTN, hypertension; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; NIMV, non-invasive mechanical failure; PSI, pneumonia severity index ; SCU , special care unit TCS, time to clinical stability.

Outcome

The mean LOS among patients who survived was 7.4±4.7 days and was statistically significant in the hypercapnic group (8.9±6.8 days, p=0.04). To investigate the correlation between LOS and TCS in steroid users, a subgroup analysis was performed. The TCS in steroid users remained higher in the hypercapnic group (4.43±2.1 mean days, p=0.01), but there was no statistically significant difference in LOS between steroid users in the three groups (p=0.49; table 2)

Table 2.

Outcomes of patients admitted with CAP

| Outcomes | Total (n=295) | Normocapnia (PaCO2=35–45 mm Hg) (n=57) |

Hypocapnia (PaCO2<35 mm Hg) (n=181) |

Hypercapnia (PaCO2>45 mm Hg (n=57) |

P Value |

| Mortality | 41 (13.89%) | 2 (3.5%) | 28 (15.46%) | 11 (19.29%) | 0.35 |

| Intubation | 56 (18.98%) | 9 (15.78%) | 35 (19.3%) | 12 (21.05%) | 0.37 |

| NIMV use | 154 (52.20%) | 15 (26.31%) | 94 (51.93%) | 45 (78.94%) | 0.03 |

| Overall LOS (mean), days |

7.3±5.0 | 9.0±5.2 | 6.24±3.5 | 9.27±7.57 | 0.009 |

| LOS (mean) in survivors, days | 7.4±4.7 | 8.7±5.1 | 6.7±3.5 | 8.9±6.8 | 0.04 |

| LOS in steroid users who survived, days |

6.3±4.4 | 6.0±3.5 | 5.86±2.9 | 7.57±7.0 | 0.49 |

| TCS in steroid users, days | 3.0±1.8 | 1.89±0.6 | 2.66±1.5 | 4.43±2.1 | 0.001 |

LOS, length of hospital stay; NIMV, non-invasive mechanical ventilation; TCS, time to clinical stability.

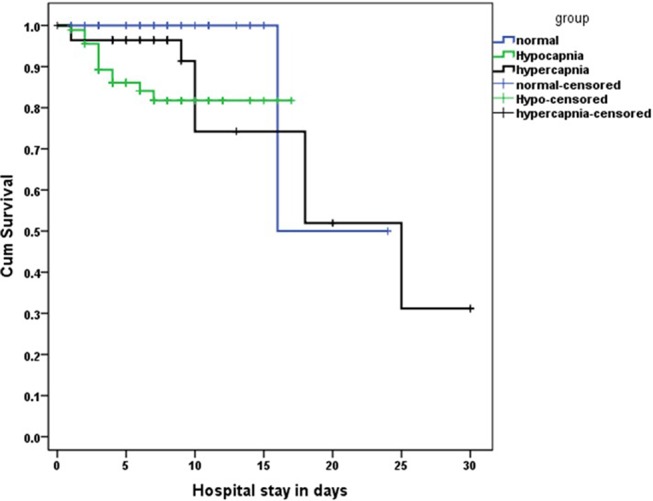

Among the three groups, ICU admission/endotracheal intubation was required in 56 (18.98%) patients, which was not statistically significant (p=0.37). NIMV was required in 154 (52.20%) patients, of which 45 (78.94%, p=0.03) were in the hypercapnic group. Overall mortality was 41 (13.89%) and the difference was not statistically significant between the groups (p=0.35). The Kaplan–Meier curve survival analysis of LOS among the three PaCO2 groups is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve showing the length of hospital stay among the three PaCO2 groups.

On univariate analysis, hypercapnia, normocapnia on admission, in-hospital mortality, IHD, asthma, use of systemic steroids, PSI score, ICU admission/intubation and NIMV were significantly associated with increased LOS. On multivariable analysis, increased LOS in patients with CAP was associated with NIMV use, ICU admission/intubation, normocapnia and hypercapnia and was significantly lower in hypocapnic patients (table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model for length of hospital stay in patients with CAP

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p Value | |

| IHD | 0.39 (0.18 to 0.81) | 0.01 |

| NIMV use | 3.48 (1.85 to 6.54) | <0.001 |

| ICU/intubations | 3.96 (1.65 to 9.50) | 0.002 |

| Mortality | 0.21 (0.08 to 0.56) | 0.002 |

| Group | ||

| Normal | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Hypocapnia | 0.13 (0.06 to 0.30) | <0.001 |

| Hypercapnia | 0.55 (0.22 to 1.39) | 0.20 |

ICU, intensive care unit; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; LOS, length of stay >7 days; NIMV, non-invasive mechanical ventilation;.

Discussion

In this observational study of CAP we found that hypercapnia on presentation is associated with greater severity of CAP, longer TCS and increased need for NIMV compared with the other groups. The increased LOS was associated with hypercapnia and normocapnia compared with hypocapnia. There was no statistically significant difference in mortality and intubations/ICU admissions between the three groups.

LOS consists of two components: TCS and the time from clinical stability to discharge. This time period is important as it translates into the cumulative cost of treatment.22 Interestingly, in our study we found that hypercapnia leads to longer TCS but, once it is achieved, the time to discharge is shorter than for the other groups. This longer TCS is probably due to increased severity of CAP at the time of presentation. TCS was also longer in the subgroup of hypercapnic patients who received adjunct steroids. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the actual LOS among the three groups of patients who received steroids. We found no significant impact of systemic steroids on reducing the overall duration of LOS and TCS, as previously noted.9 10

Our results are contrary to those reported in the studies by Laserna et al21 and Sin et al,23 which both found that hypocapnia and hypercapnia were associated with increased mortality and ICU admission in patients with CAP. Moreover, they did not find any difference in LOS among the three groups. Another study by Yassin et al24 did not find a significant relationship between PaCO2 and mortality or ICU admission. However, hypercapnia was associated with longer LOS, which was similar to our study. We found that hypercapnia correlates well with disease severity on presentation as suggested by higher CURB-65 and PSI scores in hypercapnic patients compared with other groups, a finding similar to a previous study.21

Patients with CAP can develop hypercapnia, especially when receiving high concentration oxygen therapy because of the increase in the physiological dead space, as observed in COPD.25 26 The severity of the illness itself can lead to ventilatory failure in CAP. In our study, 38.59% of patients with hypercapnia had a pH of >7.35, suggesting chronic hypercapnia. This could be due to unmasking of underlying COPD in these patients which was undiagnosed until their first presentation to us with CAP.

NIMV is a cost-effective intervention, particularly in our region where the majority are unable to bear hospital expenses. The requirement for NIMV in patients with CAP without any respiratory and cardiac illnesses has to be decided cautiously. In our study 5.08% of patients had COPD and most were in the hypercapnic group. In patients with COPD, Ahmadi et al27 showed that the level of alveolar ventilation, as reflected by both hypocapnia and hypercapnia, predicts mortality in oxygen-dependent COPD patients. However, Aida and colleagues28 found no association between PaCO2 and mortality in COPD and found hypercapnia to be a favourable factor in oxygen-dependent COPD. Confalonieri et al29 showed in a subset analysis that significant benefits of NIMV occurred in patients with COPD and hypercapnic respiratory failure, as seen in this study.

Hypercapnia causes various effects on the human body. A study suggested that, by impairing lung neutrophil function, hypercapnia increases mortality in murine Pseudomonas pneumonia.15 Hypercapnia inhibits the expression of interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor and phagocytosis in macrophages and causes a defect in resistance to pulmonary infection. This effect was found to be independent of extracellular and intracellular acidosis.16 In another study it was found that hypercapnia inhibits autophagy and bacterial killing in human macrophages by increasing the expression of B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) and B-cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-xL), which leads to immunosuppression and impaired resistance against bacteria.30 This inhibition was also not attributable to acidosis.

This is the first study from Pakistan that prospectively evaluates the association of the PaCO2 level with LOS and severity, but this study has some limitations: (1) it is a single-centre study with a small sample size; (2) as an observational study, there may have been many other unobserved confounders that could have affected our results (eg, day and time of admission, seasonality, steroid use and time to first antibiotic administration); (3) we did not study the underlying cause of death in these patients; (4) we did not study the complications developed during the hospital stay; and (5) the decision to use adjunct steroid therapy was dependent on the treating physician.

Conclusion

This study suggests that hypercapnia on admission is associated with severity of CAP, longer TCS, increased LOS and need for NIMV in patients admitted with CAP. It should be considered as an important criterion to label the severity of the illness and also as a determinant of patients who will require a higher level of hospital care to prevent the aforementioned outcomes. However, further studies are required for validation of our results.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NI has made contributions to conception and design, interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. MI has made contributions to conception and design, interpretation of data and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. AZ has made contributions to interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript. SA has made contributions to acquisition and interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript. JAK has made contributions to drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Aga Khan University ethical review committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article. No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Welte T, Torres A, Nathwani D. Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe. Thorax 2012;67:71–9. 10.1136/thx.2009.129502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, Ramirez JA. Global changes in the epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2012;33:213–9. 10.1055/s-0032-1315633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.File TM, Marrie TJ. Burden of community-acquired pneumonia in north american adults. Postgrad Med 2010;122:130–41. 10.3810/pgm.2010.03.2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Restrepo MI, Anzueto A. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2009;23:503–20. 10.1016/j.idc.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cabre M, Bolivar I, Pera G, et al. . Factors influencing length of hospital stay in community-acquired pneumonia: a study in 27 community hospitals. Epidemiol Infect 2004;132:821–9. 10.1017/S0950268804002651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halm EA, Fine MJ, Marrie TJ, et al. . Time to clinical stability in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: implications for practice guidelines. JAMA 1998;279:1452–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menéndez R, Ferrando D, Vallés JM, et al. . Initial risk class and length of hospital stay in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2001;18:151–6. 10.1183/09031936.01.00090001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takada K, Matsumoto S, Kojima E, et al. . Predictors and impact of time to clinical stability in community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia. Respir Med 2014;108:806–12. 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shafiq M, Mansoor MS, Khan AA, et al. . Adjuvant steroid therapy in community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med 2013;8:68–75. 10.1002/jhm.1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blum CA, Nigro N, Briel M, et al. . Adjunct prednisone therapy for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:1511–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62447-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torres A, Sibila O, Ferrer M, et al. . Effect of corticosteroids on treatment failure among hospitalized patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia and high inflammatory response: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;313:677–86. 10.1001/jama.2015.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortensen EM, Coley CM, Singer DE, et al. . Causes of death for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1059–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charles PG, Wolfe R, Whitby M, et al. . SMART-COP: a tool for predicting the need for intensive respiratory or vasopressor support in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:375–84. 10.1086/589754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.España PP, Capelastegui A, Gorordo I, et al. . Development and validation of a clinical prediction rule for severe community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:1249–56. 10.1164/rccm.200602-177OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gates KL, Howell HA, Nair A, et al. . Hypercapnia impairs lung neutrophil function and increases mortality in murine Pseudomonas Pneumonia. Am J Res Cell Molucular Bio 2013;49:5:821–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang N, Gates KL, Trejo H, et al. . Elevated CO2 selectively inhibits interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor expression and decreases phagocytosis in the macrophage. Faseb J 2010;24:2178–90. 10.1096/fj.09-136895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim WS, Baudouin SV, George RC, et al. . BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax 2009;64(Suppl 3):iii1–iii55. 10.1136/thx.2009.121434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. . A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:243–50. 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Confalonieri M, Potena A, Carbone G. Rossana Della Porta,Elizabeth A. Tolley, and G. Umberto Meduri "Acute Respiratory Failure in Patients with Severe Community-acquired Pneumonia". Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:1585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brochard L, Mancebo J, Wysocki M, et al. . Noninvasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 1995;333:817–22. 10.1056/NEJM199509283331301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laserna E, Sibila O, Aguilar PR, et al. . Hypocapnia and hypercapnia are predictors for ICU admission and mortality in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 2012;142:1193–9. 10.1378/chest.12-0576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortoos PJ, Gilissen C, Laekeman G, et al. . Length of stay after reaching clinical stability drives hospital costs associated with adult community-acquired pneumonia. Scand J Infect Dis 2013;45:219–26. 10.3109/00365548.2012.726737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sin DD, Man SF, Marrie TJ, et al. . Arterial carbon dioxide tension on admission as a marker of in-hospital mortality in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 2005;118:145–50. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yassin Z, Saadat M, Abtahi H, et al. . Prognostic value of on admission arterial PCO2 in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:2765–71. 10.21037/jtd.2016.10.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wijesinghe M, Perrin K, Healy B, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of high concentration oxygen in suspected community-acquired pneumonia. J R Soc Med 2012;105:208–16. 10.1258/jrsm.2012.110084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilcher J, Perrin K, Beasley R. The effect of high concentration oxygen therapy on PaCO2 in acute and chronic respiratory disorders. Trans Respir Med 2013;1:8. 10.1186/2213-0802-1-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmadi Z, Bornefalk-Hermansson A, Franklin KA, et al. . Hypo- and hypercapnia predict mortality in oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based prospective study. Respir Res 2014;15:30. 10.1186/1465-9921-15-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aida A, Miyamoto K, Nishimura M, et al. . Prognostic value of hypercapnia in patients with chronic respiratory failure during long-term oxygen therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:188–93. 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9703092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Confalonieri M, Potena A, Carbone G, et al. . Acute respiratory failure in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. A prospective randomized evaluation of noninvasive ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:1585–91. 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9903015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casalino-Matsuda SM, Nair A, Beitel GJ, et al. . Hypercapnia inhibits autophagy and bacterial killing in human macrophages by increasing expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL so lead to immunosuppression and resistance against bacteria. J Immunol 2015;194:5388–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.