Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review will catalog the many recent longitudinal studies that have investigated the relationship between asthma and lung function, or the persistence and trajectories of lung function deficits.

Recent Findings

Recent work has reported on 50-year follow-ups of some prominent population cohorts. A history of asthma confers a 10-to-30 fold risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Subjects reaching a reduced maximum growth of FEV1 in early adulthood are at risk for early or more severe COPD.

Summary

Taken together, there is a wealth of overlapping cohort studies of lung function, asthma, and COPD. These show that asthma is associated with reduced lung function, which may start in infancy or prenatally, persist through childhood and adulthood, and predispose for early or more severe COPD.

Keywords: Asthma, COPD, lung function, FEV1, longitudinal patterns of lung function

Introduction

Researchers have put forward the hypothesis that asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) should be considered different manifestations of similar and related conditions.1 According to this theory, asthma and COPD share risk factors, both environmental and genetic, and depending on a patient’s particular circumstances, that patient is more inclined to develop one or the other.2 While proof of this theory is difficult to conclusively demonstrate, it is now clear that childhood asthma is one of the first manifestations of a longitudinal lung function trajectory likely to result in eventual COPD.

Childhood asthma is associated with reductions in pulmonary function, frequently measured in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), or the ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FVC); while COPD is defined by an FEV1/FVC ratio less than 0.70. Thus, while the evidence reviewed below makes it clear that childhood asthma accompanies a lung function deficit which is likely to persist throughout adulthood, and that can in turn result in early or more severe COPD, it is still unclear whether asthma causes lower lung function, is a symptom of it, or just merely co-occurs.

Furthermore, there is a growing appreciation that asthma and COPD are not always separate conditions. In the Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS), asthma and COPD co-occur in the same patient. It is a condition characterized by a significant fixed airway obstruction and also a significant component of reversible airway obstruction, where the diagnosis of ACOS is made on a sliding scale of symptoms characteristic of asthma, of COPD, or both.3 People with asthma that persists through adulthood, together with reduced lung function, are at risk of developing ACOS and not just COPD.4 Recent work has shown that ACOS is generally more of a burden on the healthcare system,5 and confers almost double the risk of respiratory hospitalization than those with just COPD.6

Childhood Cohorts

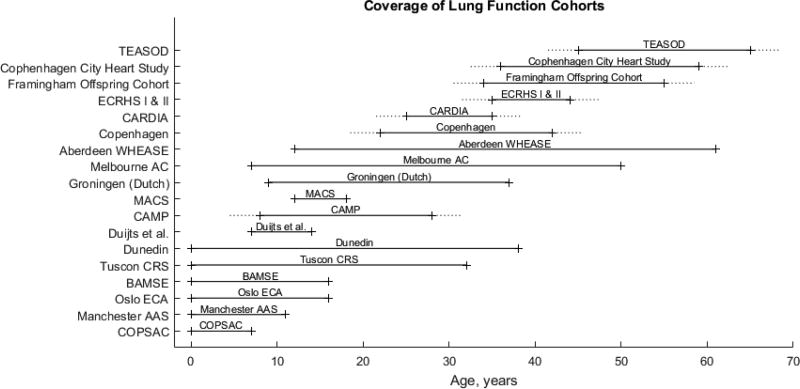

There have been many longitudinal studies of lung function, including many population studies, that have shown a relationship between childhood asthma and low lung function – either reduced FEV1, increased decline in FEV1, or premature onset of decline of FEV1 – and this low lung function predisposes to eventual COPD. However, most studies of children with asthma are short enough that subjects do not develop clinical COPD. Similarly, there have been studies of older populations where COPD is evident, and these studies have identified an association between current and remembered childhood asthma with the prevalence and onset of adult COPD. There have been few studies that have followed subjects long enough to observe childhood asthma and adult COPD in the same patients, although there are two population cohorts with 50 or more years between enrollment and latest recontact – and it seems likely that these studies will continue with even longer follow-up. By looking at the combination of population studies of pulmonary function, which span from prenatal times and infancy to at least the mid 60s (Figure 1), it is clear that childhood asthma is associated with impaired lung function which is a defining feature of adult COPD.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal cohort studies of lung function. All of these studies observed a link between asthma and low lung function or low baseline lung function and low terminal lung function. Dotted lines indicate averaged beginning and ending of trial observation. COPSAC: Copenhagen Prospective Studies on Asthma in Childhood. Manchester AAS: Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study. Oslo ECA: Environment and Childhood Asthma. BAMSE: Swedish abbreviation for Children, Allergy, Milieu, Stockholm, Epidemiology. Tucson CRS: Children’s Respiratory Study. CAMP: Children’s Asthma Management Program. MACS: Melbourne Atopy Cohort Study. Melbourne AC: Melbourne Asthma Cohort. Aberdeen WHEASE: What Happens Eventually to Asthmatic children: Sociologically and Epidemiologically. CARDIA: Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. ECRHS I & II: European Community Respiratory Health Survey I and II. TEASOD: Tucson Epidemiological Study of Airway Obstructive Disease.

The Copenhagen Prospective Studies on Asthma in Childhood (COPSAC) cohort is one of several studies to identify children at risk for asthma prenatally. COPSAC prospectively enrolled 411 at-risk children during 1998–20017, and followed them for at least seven years. By age 7, 14% had asthma, and this was associated with a lung function deficit present as infants and persisting to age 7, as well as increased bronchial responsiveness.8 Lung function deficits were also shown to increase from infancy through age 7. This study also showed a remarkable association between childhood asthma, persistent childhood wheeze, and neonatal bronchial infection.9

Similarly, the Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study (Manchester) identified prenatal children and followed them to age 11, encompassing up to 1184 subjects with at least 829 completing spirometry at any time point. This study showed that a persistent low lung function trajectory starting at age 3 was associated with subsequent persistence of wheezing, a precursor of asthma.10

Another study of prenatal asthmatics, the Environment and Childhood Asthma study, took place in Oslo, measuring lung function at birth in 329 subjects, and again at 10 and 16 years.11 The Oslo study determined that children with worse asthma or asthma with comorbidities (atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis) had impaired lung function compared to those with only asthma or those with asthma in remission, as well as to healthy controls.11

In Sweden, the BAMSE cohort study12 was designed to investigate lung function and lung function growth in relation to asthma phenotypes and symptoms. BAMSE enrolled children before birth and followed them to at least age 16, finding that asthma onset before age 4 was associated with impaired spirometric flow at age 8, regardless of intervening symptom activity; with >2700 children providing measurements.12

The Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study extended the result that infant lung function tests strongly predict adult lung function. Tucson CRS was a population cohort with 123 infants with spirometry measurements up through age 23.13 In further follow up, 599 subjects showed a stable, low lung function trajectory from age 11 to 32, with spirometry taken every 4–6 years.14 These studies demonstrate that when low lung function accompanies childhood asthma, that low lung function tends to persist into adulthood.

A long-term population cohort in Dunedin, New Zealand, brought these results further, showing that 40% of persistent childhood asthmatics have chronic airway obstruction.15 This cohort was followed from birth to age 38, comprising 1037 total subjects. They observed that FEV1 was lower in early childhood for those children that went on develop childhood asthma.15 Additionally they identified lung function groups from ages 9 to 23, where reduced lung function groups were associated with persistent wheeze.16

In a focused recruitment of young children with diagnosed, persistent, mild-to-moderate asthma, the Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) has now followed up to 1041 asthmatics from ages 5–12 years to 23–30 years.17,18 CAMP is another study that was able to associate reduced lung function with asthma.19 However, with at least annual spirometry, the CAMP study was also able to identify different trajectories that lead to adult chronic airway obstruction. It was observed that CAMP subjects could be categorized as having reduced lung function, if they were below expected FEV1 for a person of the same age, sex, height, and race; or early decline of lung function, if they tracked along normal levels of FEV1 for a time, but then began to decline earlier than expected.20 Previous work had identified a plateau period of FEV1, where FEV1 level was neither increasing with growth nor decreasing with aging, from the ages of 15 in girls or 20 in boys to age 25.21 By age 30, 11% of the CAMP subjects qualified for COPD by spirometric criteria, and these were a mix of those subjects displaying the reduced FEV1 pattern and the early decline FEV1 pattern.20

Other studies associated childhood wheeze with lung function deficits.22 One such study was the Melbourne Atopy Cohort Study (MACS), which recruited 620 children from a birth cohort with allergy or atopy, and stratified subjects by type of wheeze and allergic disease. MACS was able to show that early-onset, intermediate-onset, and late-onset wheezers were associated with lower lung function growth over the six year period from ages 12 to 18.23

A group of 119 asthmatics was followed from the age of 9 to 27 in Groningen, The Netherlands, showing that bronchial hyperresponsiveness and a low level of lung function in childhood are independent risk factors for a low level of FEV1 in early adulthood.24

A group of 346 asthmatics called the Melbourne Asthma Cohort (MAC) was recruited from a 1957 birth cohort25 at the age of 7 and followed for 50 years. The MAC cohort was able to identify children with asthma and follow them long enough to observe an increased risk of COPD at age 57, finding that baseline asthma conferred an adjusted 32-fold odds of developing COPD.26 Interestingly, they saw no differences in rate of decline of FEV1 for normal controls, persistent asthmatics, asthma in remission, and COPD.

Another cohort was followed for 50 years in Aberdeen: the WHEASE (What Happens Eventually to Asthmatic children: Sociologically and Epidemiologically) cohort of children was recruited in 1964. WHEASE included 330 subjects, from age 10–15 followed to 61. WHEASE found that childhood wheeze and childhood asthma are associated with eventual COPD.27 They also found that adult onset wheezing was also associated with COPD.

Adult Cohorts

Other longitudinal studies of adults did not directly observe childhood asthma, but frequently did directly observe adult COPD. These studies assessed the association between childhood asthma and adult COPD by using questionnaires regarding the participants’ background and a memory of diagnosis of asthma or episodes of wheeze.

A general population cohort recruited in Copenhagen followed 780 subjects from ages 7–37 for 20 years, and examined airway hyperresponsiveness, a cardinal feature of asthma. They found that airway hyperresponsiveness was associated with reduced lung function growth, noting a decrease in maximal attained lung function for airway hyperresponsiveness, independent of asthma and smoking.28

Other studies were designed to investigate the effects of smoking on lung function. The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) enrolled 3950 adult subjects up to the age of 40, and followed them for a 10 year period. Although focused on smoking, asthma was found to contribute to faster decline in FEV1 over the periods of observation compared to non-asthmatics.29 Further follow up for an additional 10 years showed that baseline lung function (FEV1 / FVC) is predictive of later lung function.30

The European Community Respiratory Health Survey I and II (ECRHS) identified several risk factors for reduced adult lung function, including asthma, parental asthma, and early life respiratory infections.31 ECRHS enrolled 7738 adults from ages 20–45, assessing spirometry and again 9 years later. In addition to reduced lung function, ECRHS also showed that early life risk factors were associated with greater decline in FEV1 across the 9 year period. ECRHS also observed onset of adult COPD, and found COPD was 10 times more likely in subjects with childhood asthma as those without, a potential impact as large as that of heavy smoking.

Other studies were combined to investigate the onset of COPD in relation to maximally obtained adult FEV1 levels. In an examination of 2864 subjects aged 35–40 and followed for an average of 22 years in the Framingham Offspring Cohort and Copenhagen City Heart Study, both lung function peak level and lung function rate of decline were important to the eventual development of COPD.32 The study determined roughly half of subjects with chronic airflow obstruction had rapid decline of FEV1, while the others had reached lower maximum values of FEV1 in early adulthood.

The Tucson Epidemiological Study of Airway Obstructive Disease (TEASOD) has contributed a number of important results related to asthma and lung function, following two-to-three thousand adult subjects for over 20 years. When considering 3099 subjects enrolled as adults (mean age ~45) and followed for 20 years with spirometry and surveys every 1–2 years, TEASOD researchers found that current asthma was associated with COPD at a 12-times hazard ratio; finding no risk for childhood and/or previous asthma.33 In subsequent examinations, TEASOD researchers found that those with asthma onset prior to age 25 were more likely to have persistent airflow limitation than those who developed asthma after age 25, and that this airflow obstruction was largely established by age 25.34 Most recently, by following 2121 adult participants enrolled in the 70s until 2015, TEASOD researchers found that baseline FEV1 predicted mortality, as did asthma, but asthma was not a risk factor for all-cause mortality after adjustment for baseline FEV1.35

Cross-Sectional Studies

These longitudinal cohort studies are the ideal method for investigating the relationship between childhood outcomes and adult outcomes – when the subjects can be followed from childhood through adulthood. However, the expense and effort required to closely follow a large cohort for a long period of time makes studies that do so rare. This problem is particularly salient in pulmonary investigations where subjects must undergo spirometric assessment at regular intervals, the more the better, and these measurements often have significant variability. Nevertheless, we still obtain useful insights from cross-sectional studies and much shorter studies, where adult COPD can be readily assessed and childhood risk factors can be investigated through questionnaires.

These include the Hiroshima COPD Cohort Study, which enrolled 9896 participants prospectively across Japan, ages 35–60, and found that remitted childhood asthma associated with significantly lower FEV1.36 The Wellington Respiratory Survey37 surveyed 749 people ages 25–75 for risk of COPD, and found that a previous diagnosis of asthma in childhood was equivalent to aging 22 years or to 62 pack-years of smoking toward the risk of COPD.38 A prospective, multisite Canadian Cohort of Obstructive Lung Disease (CanCOLD) enrolled 4893 adults aged 40 years and older, identifying independent predictors of COPD: older age; self reported asthma; and lower education.39 The Busselton Study found that lung function deficits early in life, associated with asthma and smoking, lead to later COPD.40 In a series of follow-ups of 9317 adults, Busselton showed increased decline in FEV1 for asthma subjects. An investigation into 306 adults with confirmed asthma found that smoking, longer asthma duration, absence of ICS therapy, and neutrophils in induced sputum were all risk factors for persistent airflow obstruction.41

Conclusions

There is a wealth of evidence from dozens of trials showing that asthma is associated with reduced lung function. This is also the conclusion of several other reviews of asthma and lung function.42–44 However, this leaves two important points.

First, asthma is not usually shown to be associated with clinically diagnosed COPD; and thus we may ask if lower lung function is sufficient to establish a link between asthma and COPD. Some studies have shown that airway obstruction goes largely undiagnosed in young adults.30 An examination of largely normal subjects in NHANES (National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys) III and NHANES 2007–2012 showed that subjects with undiagnosed pulmonary obstruction had increased risk of mortality relative to controls,45 although they were generally healthier than those with diagnosed lung disease. This argues that even latent airway obstruction is a condition with serious health risks.46 However, there are now some studies which do have the follow-up to observe both childhood asthma and adult COPD (Aberdeen, Melbourne), over their 50-year observation periods.

And second, there is a tradeoff between much longer follow-up and the difficulty and expense in providing detailed and frequent assessments of spirometry and morbidities, and the risk of greater losses to study drop out. In shorter studies, much more detailed observations have been conducted, for example the CAMP study provided at least annual spirometry through 16–18 years of observation. With frequent observation through the ages of 18 to 25, CAMP was able to identify early decline of lung function, as distinct from other forms of respiratory insufficiency commonly shown to lead to COPD: reduced maximal lung function and rapid lung function decline. While additional observation through these ages is needed in replication trials, this is a result that complements the others here: not only does poor lung function from early childhood pose a risk to adult lung function, but so does normal growth through childhood that then declines earlier than expected.

A number of excellent longitudinal and cross-sectional studies together draw a picture of asthma as an important risk factor and precursor to lower lung function and chronic airway obstruction. With continued investigation this picture will resolve with increasing detail and clarity. Children with asthma, especially those with more severe disease, should undergo spirometry at least annually to assess the risk of future, early-onset chronic obstruction. Assessments of environmental or therapeutic interventions should be conducted to determine if they can ameliorate poor lung function development, from neonatal interventions through adolescence. Finally, it will be important to develop new treatments and management strategies that prevent or slow lung function deterioration, and that may possibly help adolescents achieve higher maximal lung function levels in early adulthood.

Key Points.

There are dozens of studies showing an association between childhood asthma and reduced lung function.

Reduced lung function tends to persist; baseline lung function is a strong predictor of later lung function.

Several studies have shown that asthma is a risk factor for COPD or undiagnosed chronic airway obstruction.

Acknowledgments

The work presented here is the sole opinions of the author.

Financial support

MJM received funding from the Parker B Francis Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The author states that there was no conflict of interest in preparing this manuscript.

References

- 1.Orie N, Sluiter H, DeVries K, Tammeling G, Witkop J, editors. The host factor in bronchitis. Assen, The Netherlands; Royal Van Gorcum: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Postma DS, Boezen HM. Rationale for the Dutch hypothesis. Allergy and airway hyperresponsiveness as genetic factors and their interaction with environment in the development of asthma and COPD. Chest. 2004;126:96S–104S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2_suppl_1.96S. discussion 59S–61S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3*.Postma DS, Rabe KF. The Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1241–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1411863. Comprehensive discussion of Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.To T, Zhu J, Larsen K, et al. Progression from Asthma to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Is Air Pollution a Risk Factor? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:429–38. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-1932OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadatsafavi M, Tavakoli H, Kendzerska T, et al. History of Asthma in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. A Comparative Study of Economic Burden. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:188–96. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201508-507OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerhardsson de Verdier M, Andersson M, Kern DM, Zhou S, Tunceli O. Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Overlap Syndrome: Doubled Costs Compared with Patients with Asthma Alone. Value Health. 2015;18:759–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bisgaard H. The Copenhagen Prospective Study on Asthma in Childhood (COPSAC): design, rationale, and baseline data from a longitudinal birth cohort study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93:381–9. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61398-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bisgaard H, Jensen SM, Bonnelykke K. Interaction between asthma and lung function growth in early life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1183–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201110-1922OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bisgaard H, Hermansen MN, Buchvald F, et al. Childhood asthma after bacterial colonization of the airway in neonates. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1487–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belgrave DC, Buchan I, Bishop C, Lowe L, Simpson A, Custovic A. Trajectories of Lung Function during Childhood. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;189:1101–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1700OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lodrup Carlsen KC, Mowinckel P, Hovland V, Haland G, Riiser A, Carlsen KH. Lung function trajectories from birth through puberty reflect asthma phenotypes with allergic comorbidity. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallberg J, Anderson M, Wickman M, Svartengren M. Factors in infancy and childhood related to reduced lung function in asthmatic children: a birth cohort study (BAMSE) Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45:341–8. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stern DA, Morgan WJ, Wright AL, Guerra S, Martinez FD. Poor airway function in early infancy and lung function by age 22 years: a non-selective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2007;370:758–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61379-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14**.Berry CE, Billheimer D, Jenkins IC, et al. A Distinct Low Lung Function Trajectory from Childhood to the Fourth Decade of Life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:607–12. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0753OC. Looks at long-term lung function patterns from ages 11 to 32, identifying continuation of low lung function throughout observation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15**.Hancox RJ, Gray AR, Poulton R, Sears MR. The Effect of Cigarette Smoking on Lung Function in Young Adults with Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:276–84. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2492OC. Remarkable follow-up of 38 years from birth in the Dunedin study. Makes concrete observations of low lung function preceeding childhood asthma and childhood asthma preceeding chronic airway obstruction. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR, et al. A longitudinal, population-based, cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;349:1414–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP): design, rationale, and methods. Childhood Asthma Management Program Research Group. Control Clin Trials. 1999;20:91–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long-term effects of budesonide or nedocromil in children with asthma. The Childhood Asthma Management Program Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1054–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010123431501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strunk RC, Weiss ST, Yates KP, Tonascia J, Zeiger RS, Szefler SJ. Mild to moderate asthma affects lung growth in children and adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1040–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20*.McGeachie MJ, Yates KP, Zhou X, et al. Patterns of Growth and Decline in Lung Function in Persistent Childhood Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1842–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513737. This study in CAMP identifies both reduced growth and early decline as lung function trajectories that lead to COPD, which is shown to occur as early as the third decade of life. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Mensinga TT, Schouten JP, Rijcken B, Weiss ST. Determinants of maximally attained level of pulmonary function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:941–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2201011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duijts L, Granell R, Sterne JA, Henderson AJ. Childhood wheezing phenotypes influence asthma, lung function and exhaled nitric oxide fraction in adolescence. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:510–9. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00718-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, Allen KJ, et al. Childhood wheeze phenotypes show less than expected growth in FEV1 across adolescence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:1351–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1487OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grol MH, Gerritsen J, Vonk JM, et al. Risk factors for growth and decline of lung function in asthmatic individuals up to age 42 years. A 30-year follow-up study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999;160:1830–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.9812100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams H, McNicol KN. Prevalence, natural history, and relationship of wheezy bronchitis and asthma in children. An epidemiological study. Br Med J. 1969;4:321–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5679.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tai A, Tran H, Roberts M, Clarke N, Wilson J, Robertson CF. The association between childhood asthma and adult chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2014 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.Tagiyeva N, Devereux G, Fielding S, Turner S, Douglas G. Outcomes of Childhood Asthma and Wheezy Bronchitis. A 50-Year Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:23–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0870OC. Reports 50 years of follow up on the Aberdeen WHEASE, showing asthma is associated with adult COPD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harmsen L, Ulrik CS, Porsbjerg C, Thomsen SF, Holst C, Backer V. Airway hyperresponsiveness and development of lung function in adolescence and adulthood. Respiratory medicine. 2014;108:752–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apostol GG, Jacobs DR, Jr, Tsai AW, et al. Early life factors contribute to the decrease in lung function between ages 18 and 40: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:166–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2007035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalhan R, Arynchyn A, Colangelo LA, Dransfield MT, Gerald LB, Smith LJ. Lung function in young adults predicts airflow obstruction 20 years later. The American journal of medicine. 2010;123:468 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svanes C, Sunyer J, Plana E, et al. Early life origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2010;65:14–20. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.112136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32**.Lange P, Celli B, Agusti A, et al. Lung-Function Trajectories Leading to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:111–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411532. Investigates reduced growth and rapid decline lung function trajectories, showing that subjects with COPD are split between the two patterns leading to airway obstruction. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva GE, Sherrill DL, Guerra S, Barbee RA. Asthma as a risk factor for COPD in a longitudinal study. Chest. 2004;126:59–65. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guerra S, Sherrill DL, Kurzius-Spencer M, et al. The course of persistent airflow limitation in subjects with and without asthma. Respir Med. 2008;102:1473–82. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35*.Huang S, Vasquez MM, Halonen M, Martinez FD, Guerra S. Asthma, airflow limitation and mortality risk in the general population. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:338–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00108514. TEASOD cohort investiages the effects of airflow limitation, showing mortality increases are explained by airflow limitation and not prior asthma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36**.Omori K, Iwamoto H, Yamane T, et al. Clinically remitted childhood asthma is associated with airflow obstruction in middle-aged adults. Respirology. 2016 doi: 10.1111/resp.12860. A cross-sectional study of almost 10,000 subjects found that remitted childhood asthma was associated with much lower FEV1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shirtcliffe P, Weatherall M, Marsh S, et al. COPD prevalence in a random population survey: a matter of definition. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:232–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00157906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shirtcliffe P, Marsh S, Travers J, Weatherall M, Beasley R. Childhood asthma and GOLD-defined chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Intern Med J. 2012;42:83–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39*.Tan WC, Sin DD, Bourbeau J, et al. Characteristics of COPD in never-smokers and ever-smokers in the general population: results from the CanCOLD study. Thorax. 2015;70:822–9. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206938. Over 4000 subjects were examined cross-sectionally and showed that asthma was a risk factor for COPD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.James AL, Palmer LJ, Kicic E, et al. Decline in lung function in the Busselton Health Study: the effects of asthma and cigarette smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:109–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-230OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L, Gao S, Zhu W, Su J. Risk factors for persistent airflow limitation: Analysis of 306 patients with asthma. Pakistan journal of medical sciences. 2014;30:1393–7. doi: 10.12669/pjms.306.5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tai A. Childhood asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: outcomes until the age of 50. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15:169–74. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ulrik CS. Outcome of asthma: longitudinal changes in lung function. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:904–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13d35.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duijts L, Reiss IK, Brusselle G, de Jongste JC. Early origins of chronic obstructive lung diseases across the life course. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:871–85. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9981-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez CH, Mannino DM, Jaimes FA, et al. Undiagnosed Obstructive Lung Disease in the United States. Associated Factors and Long-term Mortality. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1788–95. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201506-388OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young RP, Hopkins R, Eaton TE. Forced expiratory volume in one second: not just a lung function test but a marker of premature death from all causes. The European respiratory journal. 2007;30:616–22. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00021707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]