Abstract

Objective

To describe a single U.S. perinatal referral center’s ongoing experience with evaluating pregnant patients with potential exposure to Zika virus infection.

Methods

This is an IRB approved longitudinal observational study from January – August 2016 from a single high-volume perinatal referral center. Subjects who had traveled to, or had sexual contact with a person who traveled to a region with documented local Zika virus transmission were included in the study. The aim of the study was to identify the rate of confirmed infection among pregnant women referred to our center with established risk factors for Zika virus acquisition. We also sought to characterize travel patterns that constituted risk, to identify rates of symptoms suggesting infection, and to potentially describe findings suggestive of congenital Zika virus infection in prenatal ultrasound evaluations.

Results

We evaluated 185 pregnant women with potential Zika virus exposure. Testing was offered in accordance with the version of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines in place at the time of the consult visit. Geographic exposure data showed Mexico (44%), the Caribbean (17%), North America (16%), South America (13%), and Central America (9%) to be the most common areas in which potential exposure occurred. One hundred and twenty three (67%) patients reported insect bites and 19 (10%) patients reported symptoms. Overall, 6 (3% of all) patients had prenatal ultrasound findings suggestive of possible fetal Zika virus infection; all their Zika virus test results returned negative. These findings included: microcephaly, echogenic intracardiac foci, and ventricular calcifications. Of the 153 Zika Virus screening tests ordered, 8 (5%) IgM results have returned positive or equivocal, with only 1 positive through confirmatory testing. Overall, 1/185 (0.5%) of all those consulted and 1/153 (0.7%) of those tested had a confirmed Zika virus infection, with no confirmed fetal or neonatal infections.

Conclusion

Despite low rates of confirmed infection in our current cohort, as the outbreak continues to unfold into greater geographical regions, clinicians need to be prepared to answer questions, explain laboratory and ultrasound results, and describe testing options for concerned patients and their families.

Introduction

In November 2015, the Brazilian Ministry of Health reported a 20 fold increase in the number of cases of neonatal microcephaly, a severe congenital neurologic malformation with significant long term sequelae [1, 2], which has since been linked to maternal infection with the Zika virus during pregnancy[3]. Semen and blood products have also been shown to be potentially infectious, raising concerns that non-vector borne virus plays a role in the spread of Zika. In addition, Zika-specific RNA has been detected in amniotic fluid, breast milk, seminal fluid, saliva, urine and blood, raising public health concerns for the prevention and control of Zika virus globally [4].

As the Zika virus outbreak has spread across the Americas, a spectrum of neonatal neurologic and developmental abnormalities attributable to congenital infection has been described [5]. While neurologic impact in adults has also been demonstrated, including but not limited to Guillain-Barre Syndrome[6, 7], the preponderance of pathophysiology has occurred in fetuses and newborns, producing an understandable degree of anxiety among pregnant women in areas with local transmission, as well as those pregnant women who have traveled to those regions or engaged in sexual contact with partners who have traveled to those regions [8–10]. The fact that Zika virus infection is symptomatic in only 20 percent of cases [11], and that perinatal impact has been shown in both symptomatic and asymptomatic women, has only heightened concern among women and families in Zika virus-risk areas, including, as of July 2016, those in the Miami-Dade, Florida and, most recently, the Brownsville, Texas regions of the United States[12].

Since the outbreak has been described, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued evolving guidelines for providers in the United States, regarding counseling and testing for women who are either pregnant or planning pregnancy with potential Zika virus exposure [13, 14]. These guidelines have sequentially expanded testing criteria to maximize the number of potentially infected pregnant women who are identified, as more information regarding the implications of perinatal Zika virus infection have become available.

The importance of counseling and testing of pregnant women regarding Zika virus infection and its risks has compelled providers to be current regarding guidelines as they evolve, to best guide women and their families through this outbreak. We describe the ongoing experience of a single U.S. metropolitan perinatal center regarding the triage and testing of pregnant women referred specifically for concerns regarding potential Zika virus infection. While we describe the subsequent surveillance of this population that was guided by their test results, our primary focus and intent was to more completely describe the quality of care required in providing testing and counseling to this particularly concerned cohort of patients.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a longitudinal observational cohort study at a single perinatal referral center from January-August 2016. This center provides comprehensive consultative services to providers and their patients in a large population center in Southern California. After the first CDC travel advisory surrounding Zika virus and pregnancy was issued in Feb 2016 [14], a travel history was obtained on every patient seen at our center. As expanded guidelines were published throughout the study period, testing criteria based on symptoms and exposures in pregnant women were modified accordingly [13]. Subjects were included in the study if they had traveled to, or had sexual relations with a person who traveled to a region where local Zika virus transmission had been reported. All pregnant patients who were potentially exposed to Zika virus infection between August 2015 and August 2016 were included in the data collection. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the University of California, Los Angeles (IRB# 16-000285).

We sought to identify the rate of confirmed infection among pregnant women in our referral region who had established risk factors for acquiring infection, either through personal travel or travel by a sexual partner. We also sought to characterize the travel patterns of exposure-risk for women in this region, since travel concerns comprise a significant proportion of questions received by our center on a daily basis. Lastly, we sought to describe rates of symptoms among these women suggesting Zika virus infection, as well as any findings on their prenatal ultrasounds that might raise concern for Zika virus infection. Patients were questioned, as recommended by clinical guidelines published by the CDC, about the presence of any of the following symptoms: rash, fever, conjunctivitis, myalgias, and headache [14] during travel times or immediately after return. If exposure was via sexual contact with a partner who had traveled to a high-risk region, the patient was asked if she had experienced any of these symptoms after that contact. The patient was also asked about condom use prior to and after partner exposure.

Ultrasound evaluation of patients at risk either because of positive test results, or inability to test because of timing of the patient visit, was guided by reports of Zika associated findings as described by Brasil et al., which is the largest published prospective cohort to date that followed pregnant women with confirmed Zika infection. We also referred to the consensus statement published by the World Health Organization, which describes ultrasound findings associated with congenital Zika syndrome [15]. In addition, while echogenic intracardiac foci have not specifically been linked to known Zika virus infection, they were included as a finding of concern in our study given the prior description of prenatally visualized hyperechogenic cardiac valves in cases of known neonatal Zika virus infection [16, 17]. Microcephaly was defined as head circumference measurements that were 3 standard deviations below the mean, as reinforced by a recent policy statement by the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine [18, 19].

Prior to the revised CDC guidelines of July 25, 2016 [13], Zika virus polymerase chain (PCR) testing on blood and urine were offered only to women who described Zika virus-suggestive symptoms after potential exposure. After the revised guidelines, PCR testing was offered to all women regardless of symptoms who presented within 2 weeks of potential exposure in them or a sexual partner. For those who presented 2–12 weeks post-exposure, testing was offered via the approved MAC-ELISA IgM assay. Patients with positive or equivocal IgM results had confirmatory testing of the original sample via plaque reduction neutralization testing (PRNT) in an approved reference laboratory. Testing was offered initially through public health laboratories then, later in the study period, through commercial laboratories that had been approved to conduct these tests under emergency use authorizations (EUA) from the FDA.

Descriptive statistics, as well as Kruskall-Wallis tests for non-parametric data, were used to evaluate the results .Stata 14 (College Station, TX) was used for descriptive statistics and Kruskall-Wallis tests, and EpiTools was used for the analysis of confidence intervals.

Results

During the defined study period, we identified 185 pregnant women who had potential Zika virus exposure either through travel (94%) or sexual contact (6%) [Table 1]. Time of exposure during travel is further categorized as short-term (less than 30 days in a high-risk region) or long-term (more than 30 days in a high-risk region). None of the patients with exposure secondary to sexual contact with a partner endorsed using condoms prior to evaluation in our center. Our cohort ranged in age from 25 to 51 (median age: 34). The majority of our patients were Caucasian (63%), followed by Asian (16%), Hispanic (14%), African-American (2%), and Middle Eastern (3%). The majority of patients (51%) had traveled to a Zika-risk area prior to the CDC’s initial Zika travel advisory published in February 2016, which first described expanded testing during pregnancy, independent of the woman’s symptoms. The majority of all exposures occurred either just prior to conception or during the first trimester (64%).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Number (%) with data | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (years) | Range: 25 – 51 |

| Median: 34 | |

|

| |

| Type of exposure | Short term* 169 (91) |

| Long term† 4 (2) | |

| Sexual contact 12 (6) | |

|

| |

| Index traveller | Patient 173 (94) |

| Patient’s partner 12 (6) | |

|

| |

| Location of travel | Mexico: 82 (44) |

| North America: 31 (17) | |

| Caribbean: 29 (16) | |

| South America: 24 (13) | |

| Central America: 17 (9) | |

| Asia: 2 (1) | |

|

| |

| Gestational age at time of exposure | Pre-conception: 31 (17) |

| 1st trimester: 87 (47) | |

| 2nd trimester: 57 (31) | |

| 3rd trimester: 10 (5) | |

|

| |

| Month of exposure | August-September: 6 (3) |

| October: 5 (3) | |

| November: 17 (9) | |

| December: 43 (23) | |

| January: 37 (20) | |

| February: 12 (6) | |

| March-April: 12 (6) | |

| May-July: 53 (29) | |

|

| |

| Trimester at first visit | Pre-conception: 11 (6) |

| 1st trimester: 62 (34) | |

| 2nd trimester: 68 (37) | |

| 3rd trimester: 44 (24) | |

Short term contact: Less than 30 days of residence at specified region

Long term contact: More than 30 days of residence at specified region

Geographic exposure data showed Mexico (44%), North America (17%), and the Caribbean (16%) to be the most common areas in which patients’ personal or partner exposures potentially occurred. As outbreaks of local infection began to be described and tracked in the Miami-Dade area, however, travel exposures from this region provided a large proportion of exposure cases in the later part of the study period (17% of all exposures).

Within our cohort, 67% of patients reported mosquito bites, but only 10% of patients overall reported any symptoms suggestive of Zika virus infection. The patients reporting symptoms had mostly traveled to Mexico and the Caribbean (53%).

Five patients (3%, 95% CI: 1.1%–6.2%) had prenatal ultrasound findings suggestive of possible Zika virus infection; all these findings ultimately had negative Zika virus testing results. Findings reported as potential markers for Zika virus included: microcephaly, echogenic intracardiac foci, and intracranial ventricular calcifications. All findings resolved prior to delivery or resulted in a neonate without evidence of Zika virus sequelae.

After assessment of testing appropriateness per guidelines in place at the time of the patient encounter, Zika virus-specific testing was ordered on 153 patients. The other 32 women fell outside guideline based testing time frames post-exposure, and were alternatively offered serial fetal ultrasound surveillance through the third trimester. The most common tests requested were IgM assays, in 141 patients, with the majority of these (71%, CI: 63.7%–78.0%) performed in public compared to commercial laboratories. Maternal serum PCR testing was ordered in 12 patients, almost all after the change in testing criteria in July 2016. After the FDA permitted some commercial labs to run IgM and PCR testing under an Emergency Use Authorization [20], issues of cost and turn around time, were discussed with all patients, who were then given the option of using either a commercial or public laboratory for testing. Patient lab preference appears to have been at least partly impacted by the significant differences seen in turn- around times for test results. The range and mean time for results was markedly shorter for commercial compared to public laboratories: 2 – 25 days vs. 13–158 days, median 6 vs. 34 days (p<0.001).

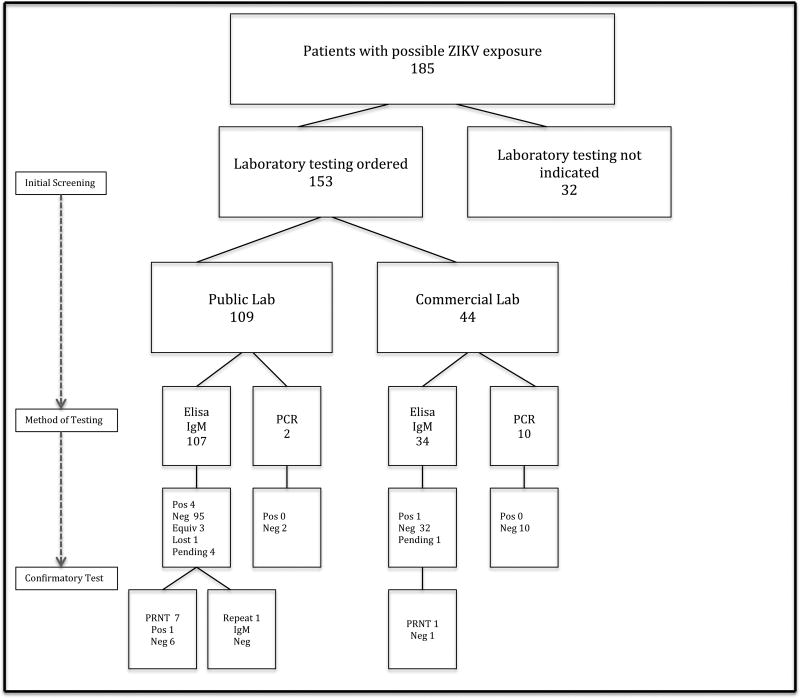

For the IgM results, 8 returned positive or equivocal (5% of all tests, CI: 2.5%–10.0%), with only 1 confirmed as positive by PRNT. Overall, 1/185 (0.5%, CI: .06%–2.5%) of all those consulted and 1/153 (0.7%, CI: .07%–3.0%) of those pregnant women tested had a confirmed Zika virus infection, with no confirmed fetal or neonatal infections [Figure 1]. The 1 woman with serologically confirmed Zika virus infection had short-term exposure (12 days) in her early first trimester, from travel to Honduras. She did report mosquito bites, but denied any symptoms suggestive of Zika infection. Intracranial calcifications were present on ultrasound evaluation in the second trimester; however ultimately resolved upon serial evaluation in the third trimester. This patient opted to undergo diagnostic amniocentesis in the 2nd trimester, with negative amniotic fluid Zika virus-PCR results. She subsequently delivered a normally grown newborn with no stigmata of ZIKV infection. PCR for Zika virus was ordered on the neonate’s cord blood; however, results are unavailable for review secondary to difficulties with laboratory processing. At three months of age, the infant has shown no signs of Zika sequelae on serial pediatric exams.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram for patient screening and diagnostic testing.

Abbreviations: ZIKV: Zika Virus, IgM: Immunoglobulin M assay, PCR: Polymerase chain reaction, PRNT: Plaque reduction neutralization test

Discussion

Pregnant patients in the Southern California region referred to our center have had potential Zika virus exposure primarily related to travel to high risk areas for local transmission, with a smaller proportion describing possible exposure via travel by a sexual partner. In our study cohort, despite extensive potential travel exposure to 23 international regions documenting local transmission of the Zika virus, including within the United States, we have, to date, confirmed only 1 maternal Zika virus infection and identified no fetal or neonatal infections. In our increasingly mobile society, a patient’s primary location of residence appeared to be an uncommon source of potential Zika virus and we believe that our center’s experience is likely generalizable to patients across the United States, because patients are still likely to travel for work or pleasure as they would outside of pregnancy. Our center’s experience suggests that the majority of patients seen by obstetric providers in this country may be those who have been exposed to the Zika virus from short-term exposure secondary to travel, compared to those who have had long-term exposure (immigrants from endemic regions) or exposure from sexual contact. We believe that this represents a common scenario in most geographical regions of this country, and thus is generalizable, with the exception of certain regions in Florida and Texas that may continue to see patients with autochthonous infection.

Recently, a report from the US Zika Pregnancy Registry reported a 6% rate of Zika virus-related birth defects [21] among women with confirmed Zika virus infection. In contrast, our study focuses on screening a large cohort of potential Zika virus- exposed pregnant patients and demonstrates that overall risk of Zika virus infection after patient or partner travel to high-risk regions is low. These data may be helpful to clinicians who are expected to continue universal Zika virus-exposure screening for their pregnant patients.

Patients may be referred for the indication of potential Zika virus exposure during pregnancy. In these cases, a heightened suspicion may have an impact on prenatal ultrasounds, resulting in an increased suspicion and increased reporting for certain ultrasound markers as Zika virus- specific findings, as may have been the case in our series. However, all the patients in our series in whom initial ultrasounds were thought to carry potential findings ultimately had negative Zika virus test results and had resolution of those ultrasound findings prior to delivery.

Strengths of this study include the prospective nature of data collection and the strict adherence to CDC and SMFM guidelines as they evolved over time. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this publication is one of the largest descriptions of screening and management of potentially Zika virus infected pregnant patients from one center. The wide range of travel exposures and the fact that the pattern of exposures is similar to those reported by the US Zika Pregnancy Registry, supports the generalizability of this study. We do recognize however, that this study is descriptive in nature and that conclusions regarding risk for fetal infection and neonatal outcomes cannot be made due to the study design and the low numbers of overall confirmed Zika virus infection.

Despite low rates of maternal infection and no cases of neonatal infection in our current cohort, as the outbreak continues to unfold, especially in potentially larger non-immune populations in the United States, clinicians need to be able to interpret and triage patient and physician concerns and to manage evaluation and testing in accordance with guidelines that are current at time of patient presentation or referral. In addition, the costs of screening sizeable populations of concerned, exposed patients who may ultimately have low rates of positive results raise issues regarding best use of limited resources. Until the latter part of this study period, however, testing was only available and performed in public laboratories, with no cost incurred by patients. As commercial testing became available, patients were offered both public and commercial options for Zika testing. However, essentially no patients opted for the lower cost public option when the lower turn around time factor for commercial laboratories was discussed, despite potential costs that could arise. These issues also need to be taken into account when counseling patients regarding testing. As the implications of perinatal Zika virus exposure and infection are consistently evolving, we found it to be particularly critical to be as current as possible through frequent referral and strict adherence to the evolving recommendations made by the CDC, in order to provide the most appropriate counseling and surveillance of Zika virus-exposed patients.

Table 2.

Clinical findings and screening results

| (n) | Yes (%) | 95% CI % | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Ultrasound findings (173) | 5 (2.9) | 1.1 – 6.2 | 12 * |

|

| |||

| Bites (185) | 123 (66.5) | 59.4 – 73.0 | 3 † |

|

| |||

| Symptoms (185) | 19 (10.2) | 6.5 – 15.3 | 8 ‡ |

| Rash | 10 | ||

| Fever | 9 | ||

| Conjunctivitis | 3 | ||

| Headache | 5 | ||

| Myalgias | 5 | ||

|

| |||

| IgM testing ordered (153) | 141 (92.2) | 87.1 – 95.6 | |

|

| |||

| PCR testing ordered (153) | 12 (7.8) | 4.4 – 12.9 | |

|

| |||

| Public laboratory (153) | 109 (71.2) | 63.7 – 78.0 | |

|

| |||

| Commercial laboratory (153) | 44 (28.8) | 22.0 – 36.3 | |

n: total number of cases with findings

Abbreviations: CI: Confidence Interval for proportions

Ultrasound evaluation was not indicated at the time of the visit

Cases where mosquito bites were possible, but patient was unsure

Patients who reported more than 1 symptom

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

SLG was supported by the NIH/NICHD Reproductive Scientist Development Program (K12 HD000849).

Footnotes

Disclosures:

* Lawrence D Platt: Speaker for Illumina and serves on their medical advisory board. Treasurer of the Perinatal Quality Foundation. Provides research support and is part of the speaker bureau for GE Medical Systems.

* The remaining authors listed have no disclosures

References

- 1.Agencia Saude. Microcefalia: Ministerio da Saude divulga boletim epidemiologico. 2015 Available from: http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/index.php/cidadao/principal/agencia-saude/20805-ministerioda-saude-divulga-boletim-epidemiologico.

- 2.Kleber de Oliveira W, et al. Increase in Reported Prevalence of Microcephaly in Infants Born to Women Living in Areas with Confirmed Zika Virus Transmission During the First Trimester of Pregnancy - Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(9):242–7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6509e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen SA, et al. Zika Virus and Birth Defects--Reviewing the Evidence for Causality. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(20):1981–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1604338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grischott F, et al. Non-vector-borne transmission of Zika virus: A systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14(4):313–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Driggers RW, et al. Zika Virus Infection with Prolonged Maternal Viremia and Fetal Brain Abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2142–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicastri E, et al. Zika Virus Infection in the Central Nervous System and Female Genital Tract. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(12):2228–2230. doi: 10.3201/eid2212.161280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krauer F, et al. Zika Virus Infection as a Cause of Congenital Brain Abnormalities and Guillain-Barre Syndrome: Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2017;14(1):e1002203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martines RB, et al. Notes from the Field: Evidence of Zika Virus Infection in Brain and Placental Tissues from Two Congenitally Infected Newborns and Two Fetal Losses--Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(6):159–60. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarno M, et al. Zika Virus Infection and Stillbirths: A Case of Hydrops Fetalis, Hydranencephaly and Fetal Demise. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valentine G, Marquez L, Pammi M. Zika Virus-Associated Microcephaly and Eye Lesions in the Newborn. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016;5(3):323–8. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhn J, Peters CJ. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2015. Arthropod-borne and Rodent-borne virus infections. 19th edition. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Network CHA. CDC guidance for travel and testing of pregnant women and women of reproductive age for zika virus infection related to the investigation for local mosquito-borne zika virus transmission in Brownsville, Cameron County, Texax. CDC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Titilope Oduyebo II, Petersen Emily E, Polen Kara ND, Pillai Satish K. Update: Interim Guidance for Health Care Providers Caring for Pregnant Women with Possible Zika Virus Exposure-United States, July 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65:739–744. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson Emily E, S E, Meaney-Delman Dana, Fisher Marc, Ellington Sascha R. Interim Guidelines for Pregnant Women During a Zika Virus Outbreak-United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65:30–33. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6502e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Organization WH. Pregnancy management in the context of Zika virus infection. In: W.H. Organization, editor. Interim Guidance Update. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brasil P, et al. Zika Virus Infection in Pregnant Women in Rio de Janeiro - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2016 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carvalho FH, et al. Associated ultrasonographic findings in fetuses with microcephaly because of suspected Zika virus (ZIKV) infection during pregnancy. Prenat Diagn. 2016;36(9):882–7. doi: 10.1002/pd.4882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chervenak FA, et al. A prospective study of the accuracy of ultrasound in predicting fetal microcephaly. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69(6):908–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications, C. Ultrasound screening for fetal microcephaly following Zika virus exposure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):B2–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Federal Drug Administration, U.D.o.H.a.H.S. Zika Virus Emergency Use Authorizations. 2016 Available from: https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/EmergencySituations/ucm161496.htm - zika.

- 21.Honein MA, et al. Birth Defects Among Fetuses and Infants of US Women With Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection During Pregnancy. JAMA. 2017;317(1):59–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]