Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the combined effect of magnesium oxide (MgO) as an alkalizer and polyethylene glycol (PEG) as a plasticizer and wetting agent in the presence of Kollidon® 12 PF and 17 PF polymer carriers on the release profile of mefenamic acid (MA), which was prepared via hot-melt extrusion (HME) technique. Various drug loads of MA and various ratios of the polymers, PEG 3350, and MgO were blended using a V-shell blender and extruded using a twin-screw extruder (16-mm Prism EuroLab, ThermoFisher Scientific) at different screw speeds and temperatures to prepare a solid dispersion system. Differential scanning calorimetry and X-ray diffraction data of the extruded material confirmed that the drug existed in the amorphous form, as evidenced by the absence of corresponding peaks. MgO and PEG altered the micro-environmental pH to be more alkaline (pH 9) and increased the hydrophilicity and dispersibility of the extrudates to enhance MA solubility and release, respectively. The in vitro release study demonstrated an immediate release for 2 h with more than 80% drug release within 45 min in matrices containing MgO and PEG in combination with PVP, when compared to the binary mixture, physical mixture, and pure drug.

Keywords: Magnesium oxide, Polyethylene glycol, Mefenamic acid, Hot-melt extrusion, Kollidon® 12 PF and 17 PF

Introduction

Mefenamic acid [N-(2,3-dimethylphenyl) anthranilic acid] is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) known to inhibit prostaglandin biosynthesis and is also a member of the fenamate group (Fig 1). Mefenamic acid (MA) is used as an anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and potent analgesic agent to treat rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, dental pain, and dysmenorrhea.1–3 According to the biopharmaceutical classification system (BCS), MA is a class II drug that exhibits high permeability and low water solubility (i.e. 20 mg/L, which is practically insoluble in water)4. This low solubility affects its rate of absorption from the GI tract and thus consequently will likely adversely affect its oral bioavailability.1,5 Solid dispersion is a promising technique for overcoming this problem; it involves processing the poorly soluble drugs with inert carriers to change the nature of the drug, i.e. converting the crystalline form of the drug into an amorphous form that subsequently improves drug solubility and further increases drug bioavailability.6,7

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of Mefenamic acid [N-(2,3-dimethylphenyl)] anthranilic acid]

Many techniques for formulating solid dispersion systems have been reported. The hot-melt extrusion (HME) technique has attracted attention in the pharmaceutical field as a novel technique with several advantages compared to other conventional techniques.8 HME is a continuous and solvent-free process and thus is considered an economical technique because it reduces processing steps and eliminates drying steps. Extrusion is the process of embedding a raw mixture of the drug, polymers, and other additives into a barrel and then forcing it through a die to produce a molten material of a uniform shape (extrudate).7,9 Materials with poor thermoplastic properties may lead to poor extrusion process ability and degradation. Adding a suitable carrier and/or plasticizer can promote the drug thermal stability by decreasing the processing temperature and enhance the extrusion processability.10 PEG is a chemical synthestic polymer which is often used in HME to enhance the solubility of a poorly soluble drug or as a plasticizer owing to its high hydrophilicity. This property gives PEGs the ability to increase the porosity, water uptake, and dispersibility of the formulations.11,12

The solubility of poorly water-soluble drugs can be improved by incorporating a hydrophilic carrier into the matrix, such as polyvinyl pyrrolidone, Eudragit, or hydroxyl propyl methyl cellulose. However, super saturation or recrystallization may limit the solubilization capacity of a such carriers.13 A pH modifier is a promising agent that increases the solubilization capacity of the drug in the microenvironment pH (pHM), since two-thirds of the active drugs are either weak acids or bases, with pH-dependent solubility.14

In the pharmaceutical field, the pHM is defined as a very thin layer surrounding drug particles that aids in water adsorption and formation of a saturated solution.14 This technique can consequently increase or decrease the pHM of the matrix by incorporating an alkalizer or acidifier, respectively.15 This can potentially result in an improvement of the solubility and/or stability of the drug, or achievement of an excellent sustained release formulation as compared to the conventional binary solid dispersion system.16,17 It has been reported that using a small amount of MgO as an alkalizer potentially increases the dissolution of the poorly soluble drug telmisartan within a solid dispersion of polyethylene glycol 6000.18,19 In this study, we found that the addition of 5% MgO can modulate the pHM up to 9.0, thus increasing the drug release of the poorly soluble drug MA from the matrices.

The purpose of this novel study was to: (1) demonstrate the effect of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) matrices on the release of the poorly water-soluble drug MA prepared using the hot-melt extrusion technique, (2) investigate the effect of PEG as a plasticizer and swelling agent in dissolution studies, (3) study the influence of MgO as an alkalizer on the modification of the microenvironmental pH of the matrices, and (4) investigate the combined effect of PEG and MgO on the drug release behavior of the formulations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Mefenamic acid (MA) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Bellefonte PA. USA); Kollidon 12PF and Kollidon 17PF were obtained as gift samples from BASF (PEGPVCLPVA, BASF, Germany). Magnesium oxide and polyethylene glycol 3350 were purchased from Fisher Scientific. All other chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade.

Methods

Thermal gravimetric analysis

Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed in order to examine the thermal stability of the pure components and physical mixture at the employed extrusion conditions (TGA, Pyris 1 TGA, Perkin Elmer). Samples weighing around 5–7 mg were placed in a platinum pan before heating from 30°C to 250°C at heating rate of 20°C/min under an inert nitrogen gas purge of 20 ml/min.

Loss on drying

For the loss on drying (LOD) test, the moisture analyzer (MB45, Ohaus) was used to measure the amount of moisture in each formulation (physical mixture and pure drug). Each sample was placed in the aluminum dish, accurately weighed on the thermo-balance of moisture analyzer, and further heated electrically at 120°C for 15 min. The moisture analyzer automatically calculated the moisture loss from the sample in this process. The % LOD was calculated using the following equation:

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC (Diamond DSC, Perkin Elmer) studies were performed to evaluate the stability and miscibility of the drug within the matrices before and after the extrusion process. Samples were weighed (2–4 mg) and placed in hermetically sealed aluminum pans before analysis at 10°C/min with a heating rate between 30°C to 250°C under an inert nitrogen gas at a flow rate of 20 ml/min. The obtained data was analyzed using Pyris manager software (Shelton, CT, USA).

HPLC analysis

A reverse phase HPLC system was used for the analysis of MA (Waters Corp, Milford, MA, USA). The reverse-phase column consisted of a Symmetry Shield (C18, 250Å~4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size). The mobile phase comprised methanol, water, and acetonitrile at a ratio of 80:17.5:2.5 v/v, respectively. The pH of the mobile phase was adjusted with phosphoric acid (85%) to 3.0. The mobile phase was degassed under vacuum conditions for 10 min. The injection volume was 20 µL and the mobile phase flow rate was adjusted at 1.0 mL/min with retention time of about 11 min. The detection wavelength was set at 225 nm and all studies were performed in triplicate (n = 3).20

Preparation of hot-melt extrudates

Before preparing the physical mixture, the polymers were separated using USP mesh screen #35 to remove any aggregations. Various drug loads of MA and various ratios of polymers, with or without PEG 3350 (plasticizer) and MgO (alkalizer), were blended using a V-shell blender (GlobePharma, Maxiblend®) at 25 rpm for 10 min (Table I). Each blend was extruded using a twin-screw extruder, ThermoFisher standard screw configuration (16-mm Prism EuroLab, ThermoFisher Scientific) at a temperature range of 100–160°C and screw speed of 100 rpm. The rod-shaped extrudates were milled using a comminuting mill (Fitzpatrick, Model “L1A”) in the knive forward configuration, with milling speed of 8000 rpm with the 0.020 round hole screen, and stored in glass vials for further analysis.

Table 1.

Formulation Design and processing conditions.

| Formulations | MA W/W% |

K12 W/W% |

K17 W/W% |

MgO W/W% |

PEG 3350 W/W% |

Extrusion Conditions |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp. °C |

Speed rpm |

||||||

| F1 | 20 | 80 | - | - | - | 145 | 100 |

| F2 | 20 | 70 | - | - | 10 | 110 | 100 |

| F3 | 20 | 75 | - | 5 | - | 120 | 100 |

| F4 | 20 | 65 | - | 5 | 10 | 110 | 100 |

| F5 | 20 | - | 80 | - | - | 150 | 100 |

| F6 | 20 | - | 70 | - | 10 | 125 | 100 |

| F7 | 20 | - | 65 | 5 | 10 | 130 | 100 |

Evaluation of MA capsules

Hot-melt extrudates equivalent to 100 mg MA were filled in HPMC capsules. In-vitro release studies were conducted for all of the formulations in 900 ml phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) as the dissolution medium utilizing an USP apparatus II (Hanson SR8) maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C for 120 minutes with a shaft rotation speed of 50 rpm (n = 3). Sample (1.5 ml) was collected at the following intervals: 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min. It was then centrifuged (Centrifuge Eppendorf 5415 R) for 8 min at 13,000 rpm and 25°C, and then analyzed using the Waters HPLC-UV system. Fresh dissolution media was added to the dissolution vessels, equivalent to 1.5 ml at each time point.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Mid-infrared spectra were collected using an FT-IR bench (Agilent Technologies Cary 660, Santa Clara, CA). The bench was equipped with a high-pressure ATR (Pike Technologies MIRacle ATR, Madison, WI), which was fitted with a single bounce diamond-coated ZnSe internal reflection element. Analysis of the spectra was performed using Resolution Pro Version 5.2.0 (Agilent Technologies) software suite.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

The surface size, shape, and structure of the pure drug and optimized formulations were evaluated using a JEOL JSM-5600 SEM. In a high-vacuum evaporator, a Hummer® 6.2 sputtering system was used to sputter coat the samples with gold (Anatech LTD, Springfield, VA). Before sputter coating, the samples of interest were mounted on adhesive carbon pads set on aluminum stubs. An accelerating voltage of 5 kV equipped with JSM 5000 software was used for imaging.

In-vitro media uptake studies

This study was conducted similar to the in-vitro dissolution studies described above. Samples were weighed and placed into the dissolution tester. Samples were withdrawn at two time points (10 and 20 min) and the excess liquid was removed by tissue paper. Samples were re-weighed Wo, placed into an oven, and dried for 24 h before re-weighing for a constant weight, W1. The percentage media uptake capacity (MUC) was calculated using the following equation:20

Measurement of microenvironmental pH (pHM)

To investigate the effect of an alkalizer on the release of MA in the dissolution, the weighed capsules were removed from the dissolution media (pH 6.8) after 10 min time intervals. The non-disintegrated capsules were removed from the dissolution and the water was strained off at ambient temperature. The pHM for each formulation was measured potentiometrically using an Oakton pH meter (pH Spear, Fisher Scientific) equipped with a contact electrode22–24

Polarized light microscopy (PLM)

Polarized light microscopy was conducted using an optical microscope (Agilent Technologies 620 IR) equipped with crossed polarizers. The images were captured at 5× and 15× magnification. Images were identified using Videum Capture software. Samples of interest were exposed to the dissolution media (pH 6.8 phosphate buffer) and observed at 0 and 30 min to understand dissolution behavior.

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)

The PXRD studies were performed using a Bruker AXS D8 ADVANCE XRD instrument (Bruker AXS, Madison, MI) at room temperature using a CuKα radiation current at 40 mA and generator voltage at 40 kV. The scanning rate was 0.5 deg/min and diffraction angles (2Ɵ) of 3–40°.

Stability studies

Analysis of the physicochemical stabilities of the extrudates was carried out for a period of 6 months to evaluate the influence of the temperature and humidity on the amorphous solid dispersion system. Corresponding samples were stored in stability chambers (Caron 6030 Environmental Test Chamber, Caron Products and Services, Marietta, OH) in closed glass vials at 25°C/60% RH conditions. Physical stability of the formulations was determined by DSC and XRD. Drug content was determined by HPLC analysis to confirm chemical stability. In-vitro drug release studies after 3 and 6 months were evaluated and the similarity factor (f2 value) was applied to compare the dissolution profile at time 0 using the following equation:25

Where Rt and Tt is the cumulative percentage of drug released from the reference and the test product, respectively, at each of the selected n time points. The f2 value or similarity factor was calculated to determine whether two dissolution profiles are similar. The two profiles are considered similar when the f2 value is between 50 and 100.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test. A difference of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant as compared with the pure MA.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Thermal analysis

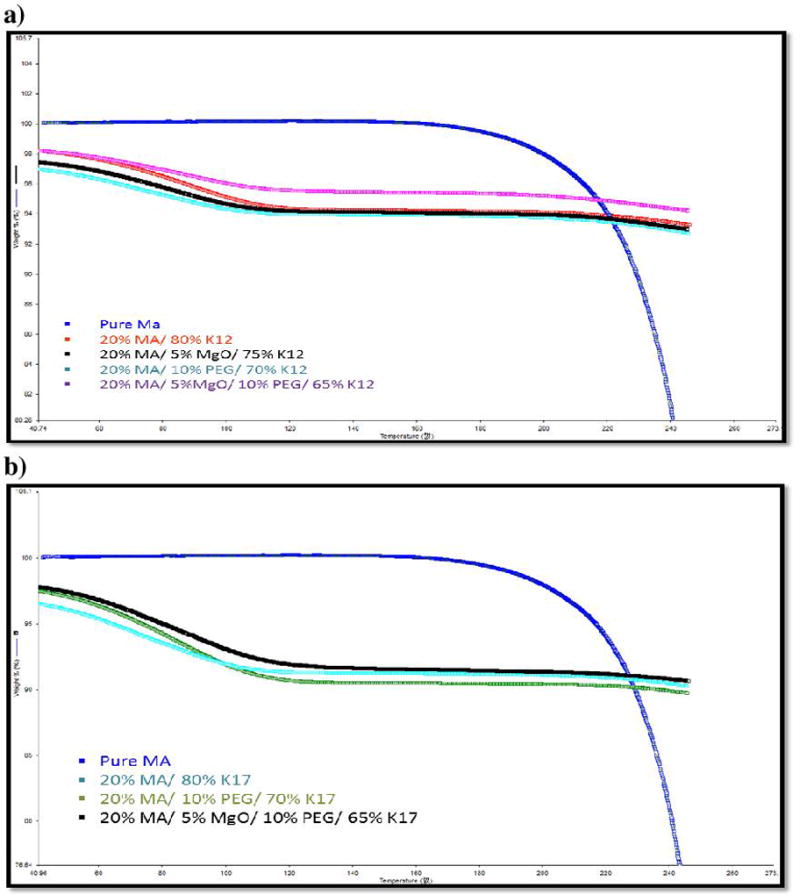

TGA analysis is generally performed before running the extrusion process to evaluate the thermal stability of the drug and physical mixture, and to make sure the excipients are thermally stable under the processing extrusion temperatures. These excipients must not degrade either at or below the extrusion processing temperature. Our results show that there was a loss in weight after heating from 30 to 250°C with a heating rate of 20°C/min, which was about 4–5% with k12 formulations and 5–7% with k17 formulations. This is considered high and may be due to drug degradation or water evaporation (Figure 2). To confirm that this loss of weight was due to moisture uptake, because PVP polymers have the ability to absorb water, we applied the LOD moisture analyzer to the mixture for 15 min at a heating temperature of 120°C. The LOD results demonstrated that there was up to 10% moisture uptake, which further supports the TGA results (Table 2). Consequently, TGA studies confirmed the stability of the drug and the polymers at the employed extrusion temperatures.

Figure 2.

TGA analysis of: a) MA/ K12 formulations, b) MA/ K17 formulations.

Table 2.

LOD analysis of Pure MA and physical mixture:

| Formulations | % LOD |

|---|---|

| F1 | 6.64 |

| F2 | 6.44 |

| F3 | 8.16 |

| F4 | 7.24 |

| F5 | 10.22 |

| F6 | 8.73 |

| F7 | 9.17 |

| Pure drug | 0.84 |

To achieve proper HME outcomes, miscibility studies of the API within the matrix had to be addressed. Solid-state characterization of MA in the matrix was carried out using differential scanning calorimetry. MA exists in two polymorphic forms, I and II.26 In the present study, form I, crystalline MA, was used. Form I has two endothermic peaks, a small one at 175°C and a more significant, sharp peak at 230°C. The K-series of 12 and 17 polymers display a glass transition temperature at 90°C and 138°C, respectively.7,35 Polyethylene glycol (PEG 3350) and magnesium oxide (MgO) have melting point at 53–59°C and 2,852°C, respectively.26, 27 The melting endothermic peaks were not observed in the extrudates in all formulations up to 20% drug load, indicating that the drug was completely transformed into an amorphous state after the extrusion process. Therefore, the DSC studies of the pure drug and the extrudates demonstrated miscibility of drug and PVP polymers, as the corresponding sharp peak representative of the drug’s melting point at 230°C was not observed (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pure MA and extrudates miscibility studies using DSC at temperatures of 30–250°C and heating rate of 10 °C/min, a) PVP K12 formulations, b) PVP K17 formulations.

Hot-melt extrusion process with MA

Before beginning the experiment, the HME process could be adjusted and optimized by studying the physical-chemical properties of the API and other materials. Choosing the appropriate excipients is highly recommended in order to formulate suitable HME products. These excipients should have some elastic behavior, i.e. they should be able to deform and pass easily through the extruder during processing and should solidify after extrusion from the die36. MA is considered a challenging drug to process via HME owing to its high melting point (230°C), which indicates high crystallinity and sticking behavior during manufacturing. Two polyvinylpyrrolidine (PVP) grades with various molecular weight and glass transition temperatures were selected as main carriers. They possess amorphous hydrophilic properties that aid in producing solid dispersions via HME technology. PVP is an efficient carrier due to its ability to inhibit drug recrystallization and decrease molecular motion of the amorphous drug, leading to a more stable solid dispersion system.19 PVP K12 has low Tg (90°C) with a high degradation temperature, which makes it easier to process during HME (Table 1).

Adding a plasticizer to the formula reduces the processing temperature and facilitates the extrusion process, thus decreasing the degradation of the drug and polymers. There were no issues during the extrusion process when MgO was added to the formulations owing to the low Tg of the polymer, K12. However, K17 has a high Tg (139°C) with a degradation temperature around 175°C, which makes it difficult to process using HME under 175°C without a plasticizer, especially when MgO is added to the formulations.

Therefore, MA and the polymers with and without a plasticizer were extrudable at the processing conditions previously stated (Table 1). However, K17 combined with an alkalizer was not extrudable without a plasticizer.

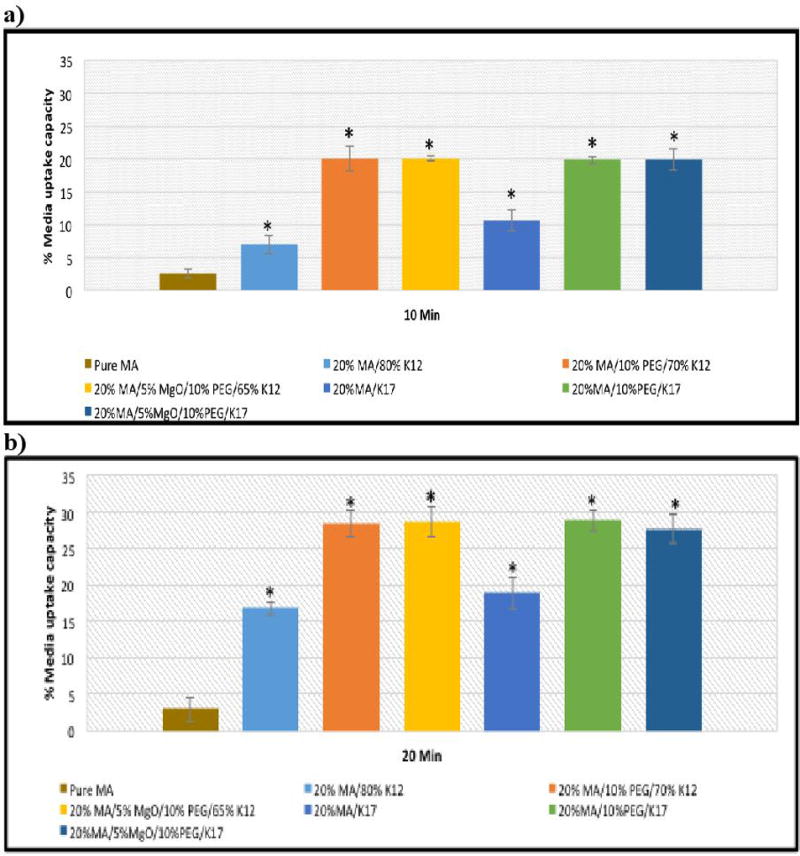

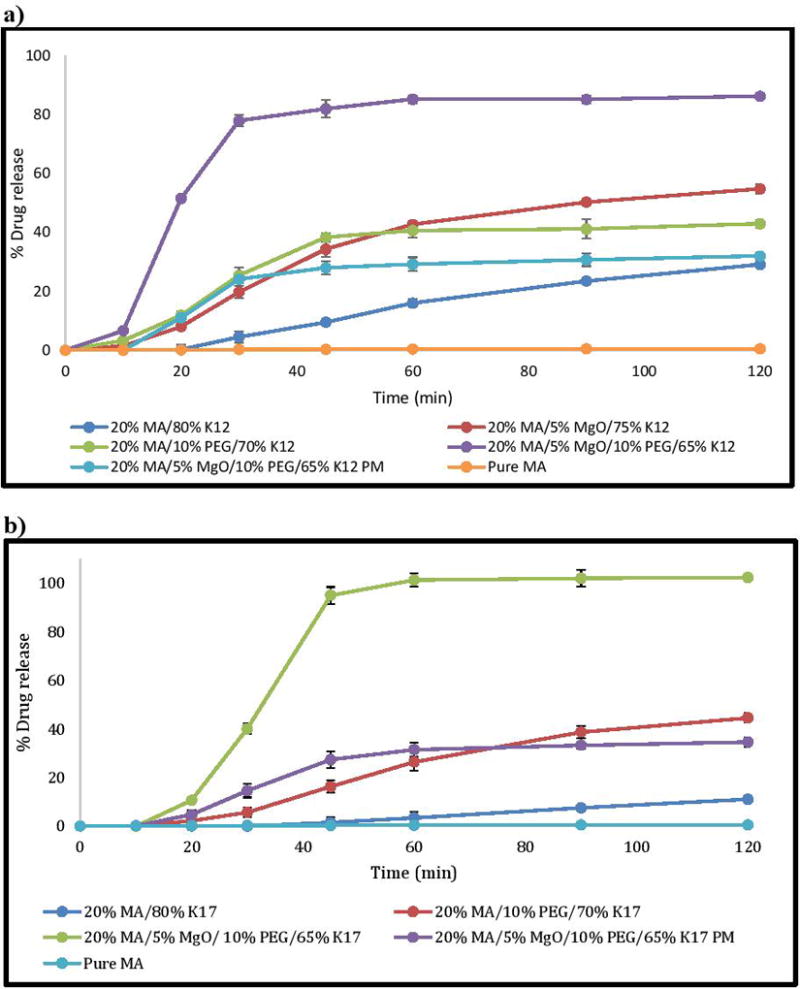

In vitro drug release studies

The dissolution profile of the pure drug, physical mixture, and solid dispersions in simulated intestinal fluid (pH 6.8) is shown in the figure 3. The release of the pure drug was less than 1% within first hour owing to the hydrophobic nature of the drug; the drug particles were not in contact with the media and did not dissolve. However, the binary solid dispersion of MA with K12 and K17 exhibited remarkable drug release, at less than 40% and 20% within 120 min, respectively. In this case, the extrudates had limited effect on the drug release even though the drug was transformed into an amorphous form. This low release was hypothesized to be due to the aggregation and agglomeration of the mixture in the dissolution media, because the drug did not dissolve well in the PVP polymer carrier. The difference in drug release between the two polymers was because of the difference in the viscosity, molecular weight, and water uptake ability. Thus, we hypothesized that adding a wetting or dispersion agent would have a strong effect and reduce or prevent aggregation and agglomeration.

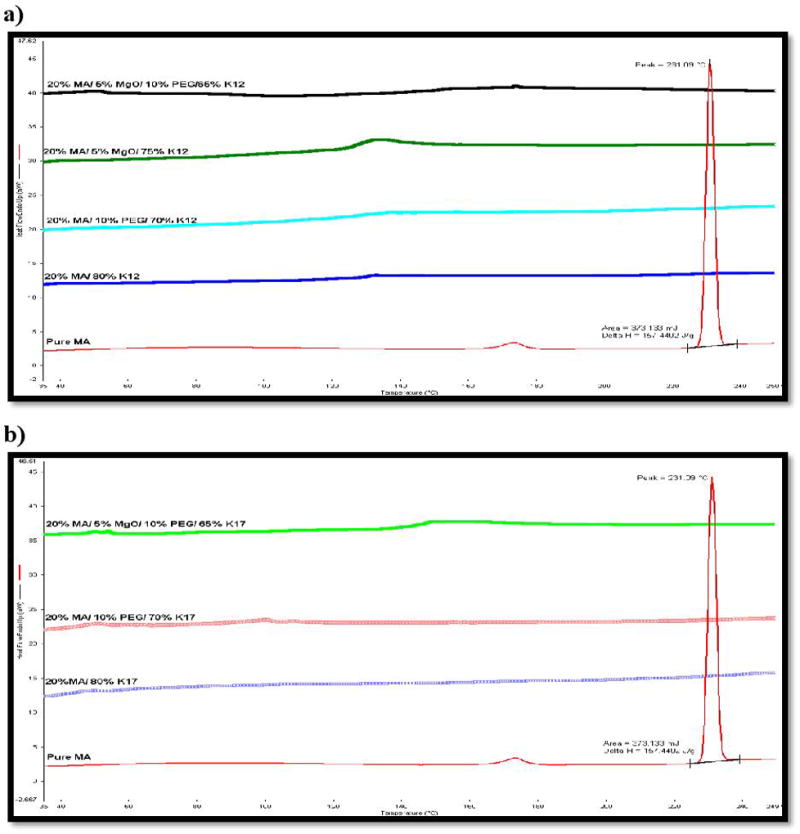

Polyethylene glycols (PEGs) are usually used as a plasticizer in the HME process due to their low melting point, low toxicity, and low cost.6 It has been reported that PEG has the ability to increase the wettability and dispersibility of the mixture directly after contact with water.29, 30 Therefore, PEG 3350 was incorporated into the HME process to facilitate the extrusion process as well as improve drug release by increasing the capability of the matrix to absorb more media and increase drug-polymers dispersibility, leading to increased drug release. Adding PEG 3350 to the formulations enhances the drug release dissolution to 10–30% of the binary mixture by inhibiting aggregation and agglomeration. In addition, we confirmed our hypothesis by studying how much media the matrix would absorb during the dissolution process. Media uptake results indicate that the pure drug media uptake rate increased from 2.6% to 7–12% with K-Series (12 & 17) PVP polymers. Adding PEG 3350 to the formulations increased the media uptake to 20–23% at the 10 min time point. The media uptake after 20 min of exposure increased from 2.9% to approximately 29% of the pure drug and MA in the extrudates, respectively (Figure 5). The water uptake study corresponded with the dissolution behaviors of the drug and extrudates as a function of time.

Figure 5.

Media uptake studies of pure ding and extrudates after: a) 10 min. and b) 20 min.

However, increasing water uptake ability is not sufficient to achieve high drug release. It has been reported that modifying the pHM could have a strong positive effect on the solid dispersion system. Incorporating an alkalizer or acidifier to the formula would modulate the pHM and thus be beneficial in enhancing the solubility of weakly acidic or basic poorly soluble drugs, respectively.

Tran et al. (2008) has investigated the use of nine alkalizers to modulate the pHM of a solid dispersion of Telmisartan and PEG 6000. They found that there was no significant increasing in the drug dissolution of the binary solid dispersion without an alkalizer. Moreover, among the nine alkalizers, a small amount of MgO (3%) demonstrated the highest modulation of pHM, leading to enhancement of drug dissolution.19 Tran et al. (2011) continued their work and studied MgO release behavior and its potential effect on Telmisartan in gastrointestinal tissue. They reported that MgO increases the pHM and thus increases the release of the insoluble model drug.16

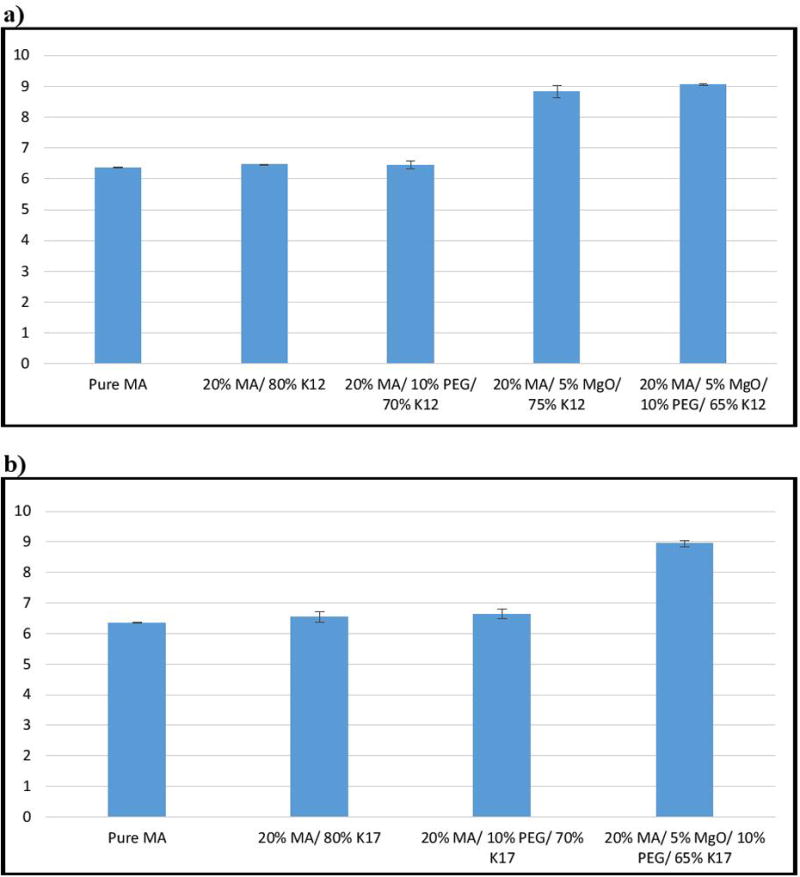

MgO was chosen as an alkalizer in the present study owing to its strong alkalizing effect and thermally stability. Furthermore, it has been reported in the literature to be a powerful agent that can increase pHM. Incorporating MgO into the binary mixture of MA-K12 increased the dissolution of the drug to around 20%, compared with the binary mixture, and 40% compared to the pure drug MA. We have confirmed these results by measuring the pHM of the formulations within the dissolution media. We found that incorporation of MgO into the formulations increases the pHM to about 9, which allows the drug to easily ionize and dissolve since the drug is weakly acidic in nature (Figure 6). The pH of the drug and other formulations was maintained between 6–6.5; it is evident that in the absence of MgO, the pHM of the formulation would not increase to the pHM of the alkaline media and ionize the drug, thus decreasing its solubility. However, adding MgO to the binary mixture (MA-PVP) resulted in less than 50% drug release within 2 h, with more than half of the drug remaining undissolved in the dissolution media.

Figure 6.

pH analysis of pure drug and extrudates: a) K12 formulations, b) K17 formulations.

Interestingly, we found that incorporating 5% MgO and 10% PEG 3350 together within the binary mixture significantly increased drug release, resulting in more than 80% dissolution within one hour for the binary mixture with both K12 and K17. We also found that the formulation containing K12 had a more rapid release, reaching 85% within 2 h, whereas the other formulation with K17 demonstrated slower release, reaching 100% drug release. This is probably due to the differences in the molecular weight and viscosity of the polymers. Increasing the amount of MgO to 10% did not affect the formulation containing K12, but resulted in faster release with K17, since MgO interfered more strongly with the API’s particles with rapid modulation of the pHM.

Therefore, the dissolution rate was found to significantly increase after incorporation of an alkalizer and PEG into the formulations, when compared to that of the pure drug, physical mixture, and binary mixture with PVP. It is evident that PEG 3350 led to an increase in the media uptake and MgO modified the microenvironmental pH inside the extrudate to be highly basic, resulting in an enhanced MA dissolution rate.

Physico-chemical properties of extrudates

The FT-IR, PXRD, SEM, and PLM studies were performed to understand the mechanism of action of the extrudates, as well as to observe the changes after extrusion.

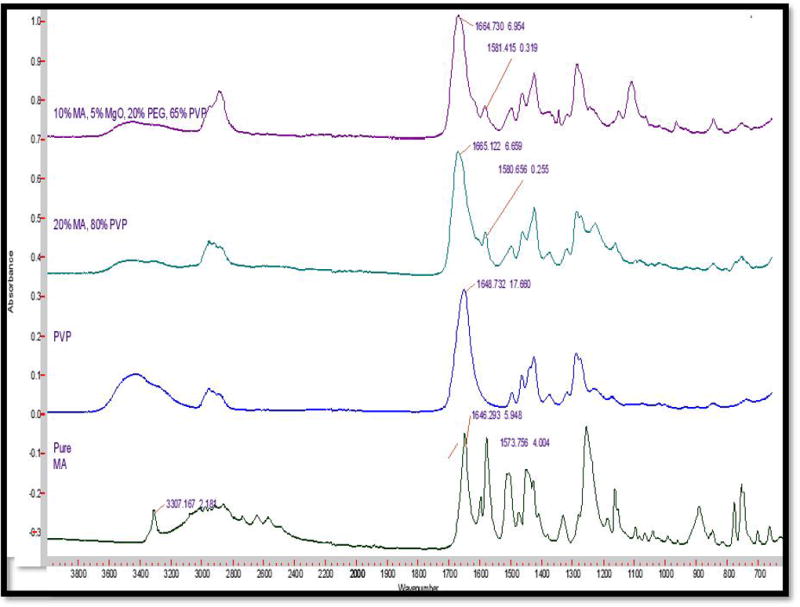

The FT-IR spectra indicate that there is an extrusion-induced intermolecular interaction between MA and the K-Series (12 & 17) PVP polymers. Figure 7 displays the individual spectra for the raw materials for comparison with the extruded formulations. The carbonyl in PVP, a most likely hydrogen bond acceptor, was originally centered at 1651 cm−1 before making a noteworthy shift to 1661 cm−1 in the extruded formulation. Likewise, there is a complimentary shift in the MA amino group, a likely hydrogen bond donor, from 1574 cm−1 to 1580 cm−1. The decrease in the observed absorption intensity from this amino group is attributed to APIs' dilution in the polymer relative to the reference spectrum. It is also possible that the hydroxyl portion of the carboxylic acid group present on MA is also participating in the newly formed bond. However, taking into consideration the strong, broad absorbance of the PVP carbonyl centered near 1650 cm−1, as well as the carrier and API’s relative proportions (80% and 20% respectively), it is not possible to distinguish any changes to the hydroxyl’s infrared signature due to the stated spectral overlap. In either case, the formation of post-extrusion hydrogen bonds is strongly indicated by these spectral shifts. Additionally, the spectra containing magnesium oxide and PEG did not seem to alter the spectral absorptions in these specified regions and were therefore considered to be uninvolved in the observed hydrogen bond formation (Figure 7). It is also worth noting that these spectral characteristics were apparent in all of the formulations, as the only difference in the carriers was one of molecular weight and not chemical composition.

Figure 7.

FTIR analysis of pure drug, polymer and extrudates.

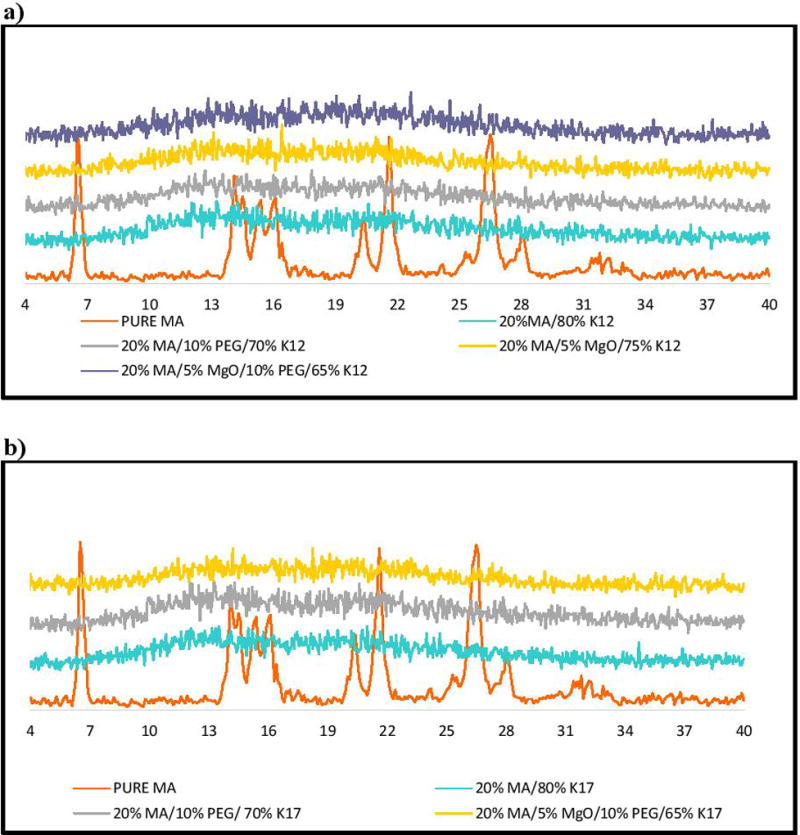

Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) measurements were used to study the crystallinity of the MA in the extrudates. The PXRD diffraction pattern of pure MA demonstrated highly intense and sharp peaks at 2θ = 6.3, 21.4, and 26.3, confirming the crystalline structure of the pure API. However, the PXRD analysis of various formulations after extrusion did not exhibit any traces of crystallinity as all sharp peaks had disappeared, indicating that the drug had completely transformed into an amorphous structure and had formed a solid dispersion in those matrices (Figure 8). These results further confirm the DSC data, where the absent melting endothermic peaks of MA indicated the formation of a solid dispersion system by HME.

Figure 8.

PXRD analysis for pure MA and extrudates, a) PVP K12 formulations, b) PVP K17 formulations.

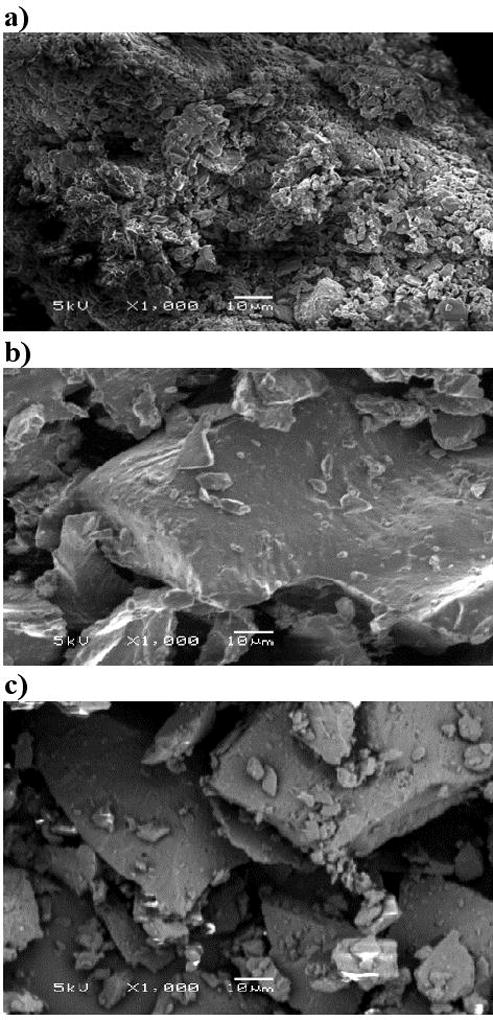

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used to investigate the surface morphology of the pure drug and extrudates (Figure 9). If the drug is in the crystalline form, the SEM images would not be smooth and show a coarse surfaces38,39. In this study, we found that the surface morphology of pure MA consists of microcrystalline aggregates with a coarse surface, which explains the crystallinity and poor water solubility of this compound. However, the extrudates, including MgO and PEG within the binary mixture of MA-PVP, exhibited fewer aggregates, and a large smooth surface.

Figure 9.

SEM images of a) pure MA, b) 20% MA/ 5% MgO/ 10% PEG/ K12, c) 20% MA/ 5% MgO/ 10% PEG/ K17.

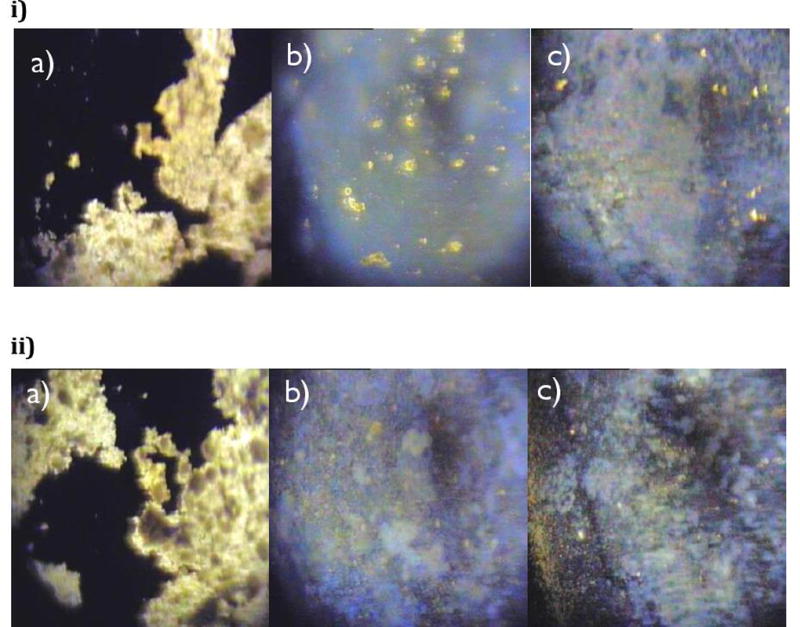

Polarized light microscopy (PLM) is a technique that has been used to differentiate between crystalline and amorphous form of the particles, since crystal structures have different refractive indices that are usually birefringent. They can be determined under polarized light microscope as a brilliant color that cannot be seen in the amorphous form.31 PLM was applied to compare the pure drug and extrudates and to study the dissolution behavior of the two optimized formulations (20% MA/ 5%MgO/ 10%PEG/ 65%K12 & K17). Figure 9-A shows that the pure drug crystals exhibited large crystal birefringence even after 30-min exposure to phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). Interestingly, extrudates rapidly dissolved once exposed to the dissolution media, with no vivid color, confirming that the drug exhibited in an amorphous form (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

PLM of a) pure MA, b) 20% MA/ 5% MgO/ 10% PEG/ K12, c) 20% MA/ 5% Mgo/ 10% PEG/ K17, after exposure to phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) at: i) 0 min, ii) 30 min.

According to these studies of physical-chemical properties, it was determined that after incorporation of PEG 3350 and MgO to PVP-based extrudates, an amorphous solid dispersion with hydrogen bonding was able to be prepared that increased the amount of water uptake and the pHM, resulting in the rapid and fast dissolution profiles of MA.

Stability studies

One of the critical problems that can limit the commercial outcomes of solid dispersions is the physical and chemical stability of the blends.31 Recrystallization of the drug in the amorphous systems usually occurs with aging due to the high free energy of amorphous molecules compared to the crystalline form. The addition of a suitable polymer can delay this crystallization phenomena according to many studies.33 The viscosity of the polymer, as well as the intermolecular interactions (hydrogen bonds) that can occur between the API and the polymer, are most important factors in the stabilization of solid dispersion systems32 Fitzpatrick et al. (2002) studied the effect of temperature and humidity on the stability of PVP formulations. They found that the PVP formulations at a high temperature and humidity (accelerated conditions) modified it from a glassy to rubbery state. However, this transformation did not occur when PVP was stored over long term conditions (61 weeks) at 30°C/60% RH.34

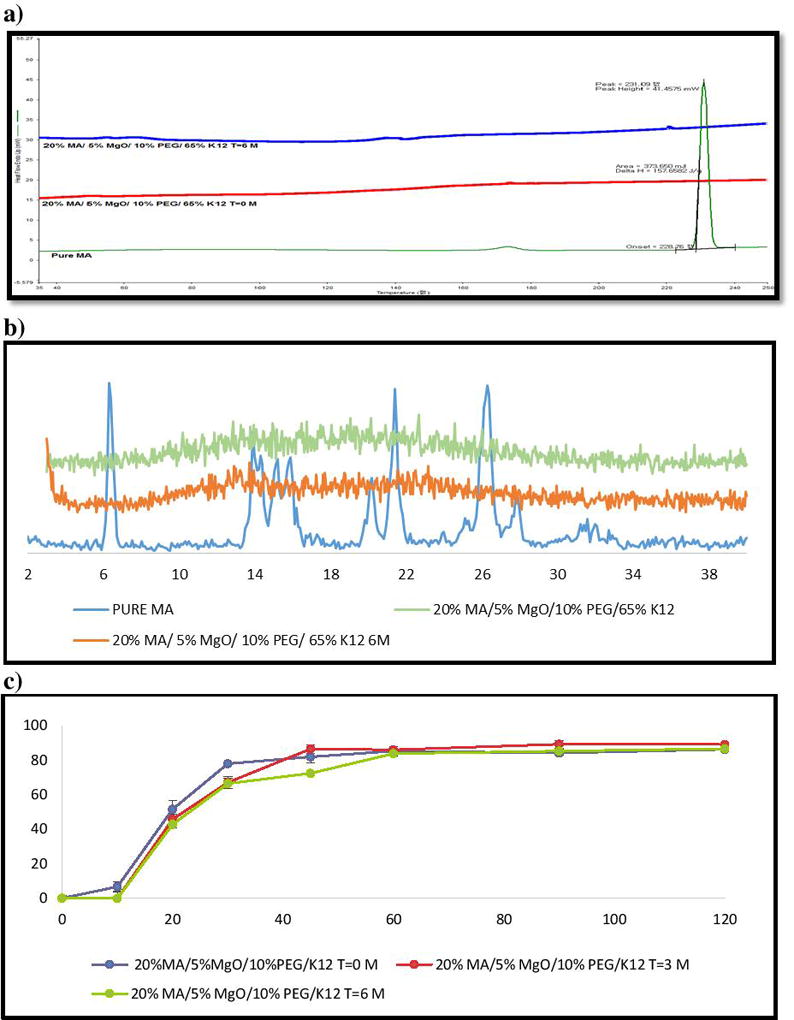

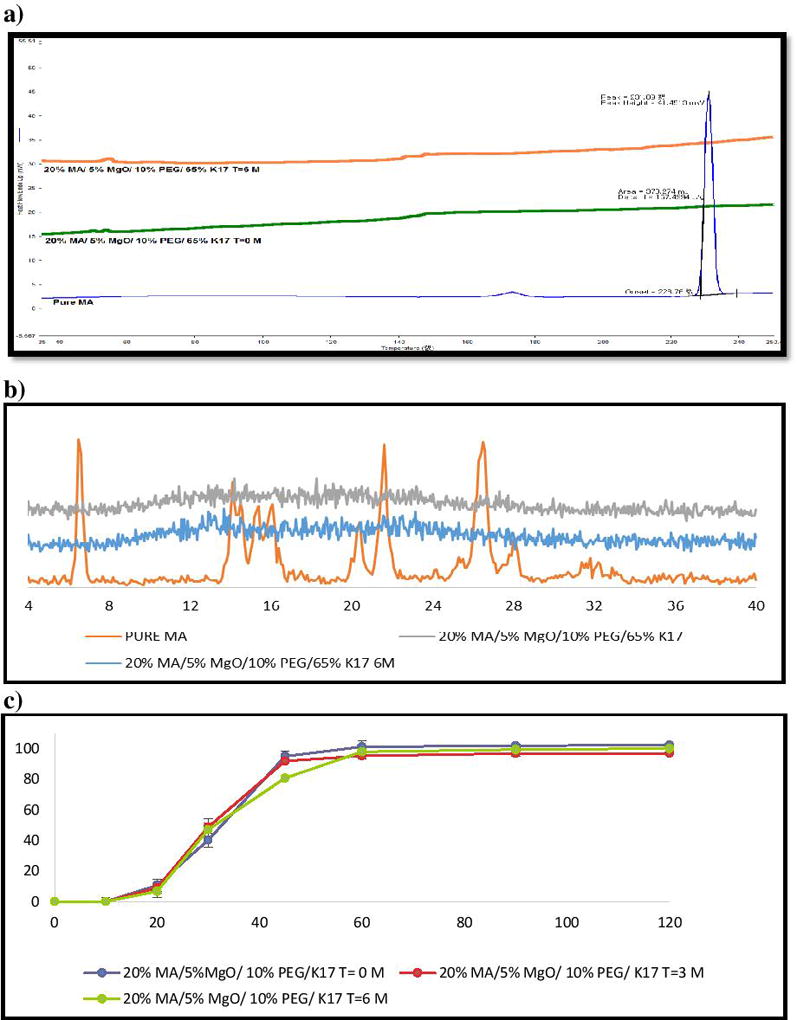

In the present study, we stored our samples of interest for a period of 6 months at normal conditions (25°C/60% RH). Assay of MA in the extrudates confirmed that the extrudates were chemically stable, with no drug degradation when analyzed for the drug content after storage duration (>99%, within 1% difference)37. DSC analysis demonstrated that the drug remained in an amorphous form, as the corresponding endothermic peak was not present after 6 months of storage (Figure 11-a & 12-a). Furthermore, drug crystalline peaks were absent in XRD, and no recrystallizations were found (Figure 11-b & 12-b). In addition, in-vitro drug dissolution studies were applied to check for any modifications that might have occurred with time and compare the formulation with fresh ones. The f2 value for k12 formulations after 3 and 6 months were 57% and 53%, respectively. The k17 formulations after 3 and 6 months of storage time were 59% and 54%, respectively. Therefore, we can conclude that the drug release profiles after long-term storage were similar to the ones at time 0.

Figure 11.

Stability test (25°C/60% RH) for 6 months of MA/PVP K12 extrudates: (a) DSC results; (b) PXRD data; (c) Drug release of extrudates in phosphate buffer (pH 6.8).

Figure 12.

Stability test (25°C/60% RH) for 6 months of MA/PVP K17 extrudates: (a) DSC results; (b) PXRD data; (c) Drug release of extrudates in phosphate buffer (pH 6.8).

Thus, the 6-month stability studies for the hot melt extrudates suggest that the extrudates were physically and chemically stable and identical to the fresh extrudates.

Conclusion

The thermal stability of each blend at the employed extrusion temperatures was confirmed by TGA analysis. All formulations were successfully extruded under the employed extrusion parameters. DSC revealed that the MA was completely miscible up to 20% w/w drug load extrudate. PXRD confirmed that the drug was in an amorphous form after extrusion. The formation of post-extrusion hydrogen bonds is strongly indicated between MA and the K-Series (12 and 17) PVP polymers. Different grades of Kollidon® had an effect on the solubility of MA by transforming the drug crystals into an amorphous configuration to form a solid dispersion system. Moreover, adding an alkalizer to the formulation has a marked positive effect on its dissolution rate by increasing the pHM to almost 9 and alkalizing the surrounding area. Incorporating PEG 3350 into the formulations significantly increased media uptake, owing to the wettability and dispersability effect of PEG. Kollidon® is a promising carrier with which to produce solid dispersion formulations by hot melt extrusion for poorly water-soluble drugs. Furthermore, the addition of an alkalizer with a plasticizer to the formulation had significant influence on the release of this API from the Kollidon® matrices.

Figure 4.

In vitro dissolution testing of physical mixture and extrudates in phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), a) PVP K12 formulations, b) PVP K17 formulations.

Acknowledgments

This project was partially supported by Grant Number P20GM104932 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), a component of NIH.

References

- 1.Sriamornsak P, Limmatvapirat S, Piriyaprasarth S, Mansukmanee P, Huang Z. A new self-emulsifying formulation of mefenamic acid with enhanced drug dissolution. AJPS. 2015;10.2:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kormosh Z, Matviychuk O. Potentiometric determination of mefenamic acid in pharmaceutical formulation by membrane sensor based on ion-pair with basic dye. Chinese Chem Lett. 2013;24:315–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdolmohammad-Zadeh H, Morshedzadeh F, Rahimpour E. Trace analysis of mefenamic acid in human serum and pharmaceutical wastewater samples after pre-concentration with Ni–Al layered double hydroxide nano-particles. JPA. 2014;4:331–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00784

- 5.Alshehri SM, Park JB, Alsulays BB, Tiwari RV, Almutairy B, Alshetaili AS, Repka MA. Mefenamic acid taste-masked oral disintegrating tablets with enhanced solubility via molecular interaction produced by hot melt extrusion technology. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2015;27:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kindermann C, Matthée K, Strohmeyer J, Sievert F, Breitkreutz J. Tailor-made release triggering from hot-melt extruded complexes of basic polyelectrolyte and poorly water-soluble drugs. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2011;79:372–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowley MM, Zhang F, Repka MA, Thumma S, Upadhye SB, Kumar Battu S, Martin C. Pharmaceutical applications of hot-melt extrusion: part I. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2007;33:909–26. doi: 10.1080/03639040701498759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morott JT, Pimparade M, Park JB, Worley CP, Majumdar S, Lian Z, Repka MA. The effects of screw configuration and polymeric carriers on hot-melt extruded taste-masked formulations incorporated into orally disintegrating tablets. J Pharm Sci. 2015;104:124–34. doi: 10.1002/jps.24262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singhal S, Lohar V, Arora V. Hot melt extrusion technique. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schilling SU, Bruce CD, Shah NH, Malick AW, McGinity JW. Citric acid monohydrate as a release-modifying agent in melt extruded matrix tablets. Int. J. Pharm. 2008;361:158–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanković M, Frijlink HW, Hinrichs WL. Polymeric formulations for drug release prepared by hot melt extrusion: application and characterization. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20:812–823. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saharan V, Kukkar V, Kataria M, Gera M, Choudhury PK. Dissolution enhancement of drugs. Part I: technologies and effect of carriers. Int J of Health Res. 2009;2 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sikarra D, Shukla V, Kharia AA, Chatterjee DP. Techniques for solubility enhancement of poorly soluble drugs: an overview. JMPAS. 2012;1:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang M, He S, Fan Y, Wang Y, Ge Z, Shan L, Gao C. Microenvironmental pH-modified solid dispersions to enhance the dissolution and bioavailability of poorly water-soluble weakly basic GT0918, a developing anti-prostate cancer drug: Preparation, characterization and evaluation in vivo. Int. J. Pharm. 2014;475:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dvořáčková K, Doležel P, Mašková E, Muselík J, Kejdušová M, Vetchý D. The Effect of acid pH modifiers on the release characteristics of weakly basic drug from hydrophlilic–lipophilic matrices. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2013;14:1341–1348. doi: 10.1208/s12249-013-0019-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran TTD, Tran PHL, Choi HG, Han HK, Lee BJ. The roles of acidifiers in solid dispersions and physical mixtures. Int. J. Pharm. 2010;384:60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siepe S, Herrmann W, Borchert HH, Lueckel B, Kramer A, Ries A, Gurny R. Microenvironmental pH and microviscosity inside pH-controlled matrix tablets: an EPR imaging study. J Control Release. 2006;112:72–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phuong HLT, Tran TTD, Lee SA, Nho VH, Chi SC, Lee BJ. Roles of MgO release from polyethylene glycol 6000-based solid dispersions on microenvironmental pH, enhanced dissolution and reduced gastrointestinal damage of telmisartan. Arch Pharm Res. 2011;34(5):747–55. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0508-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tran PHL, Tran HTT, Lee B-J. Modulation of microenvironmental pH and crystallinity of ionizable telmisartan using alkalizers in solid dispersions for controlled release. J Control Release. 2008;129:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews GP, AbuDiak OA, Jones DS. Physicochemical characterization of hot melt extruded bicalutamide-polyvinylpyrrolidone solid dispersions. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99(3):1322–35. doi: 10.1002/jps.21914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreye F, Siepmann F, Siepmann J. Drug release mechanisms of compressed lipid implants. Int. J. Pharm. 2011;404:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ha NS, Tran TTD, Tran PHL, Park JB, Lee BJ. Dissolution-enhancing mechanism of alkalizers in poloxamer-based solid dispersions and physical mixtures containing poorly water-soluble valsartan. Chem Pharm Bull. 2011;59:844–50. doi: 10.1248/cpb.59.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tran TT-D, Tran PH-L, Lee B-J. Dissolution-modulating mechanism of alkalizers and polymers in a nanoemulsifying solid dispersion containing ionizable and poorly water-soluble drug. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009;72(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patil H, Tiwari RV, Upadhye SB, Vladyka RS, Repka MA. Formulation and development of pH-independent/dependent sustained release matrix tablets of ondansetron HCl by a continuous twin-screw melt granulation process. Int. J. Pharm. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Food and D. Administration, Guidance for industry: waiver of in vivo bioavailability and bioequivalence studies for immediate-release solid oral dosage forms based on a biopharmaceutics classification system. Food and Drug Administration; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romero S, Escalera B, Bustamante P. Solubility behavior of polymorphs I and II of mefenamic acid in solvent mixtures. Int. J. Pharm. 1999;178:193–202. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(98)00375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh CM, Heng PWS, Chan LW. Influence of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose on metronidazole crystallinity in spray-congealed polyethylene glycol microparticles and its impact with various additives on metronidazole release. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2015:1–11. doi: 10.1208/s12249-015-0320-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Naser QA, Zhou J, Wang H, Liu G, Wang L. Synthesis and optical properties of MgO-doped ZnO microtubes using microwave heating. Opt. Mater. 2015;46:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minhaz MA, Rahman MM, Ahsan MQ, Rahman MH, Chowdhury MR. Enhancement of solubility and dissolution properties of clonazepam by solid dispersions. Int. J. of Pharm. & Life Sci. 2012;3:1510–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang D, Kulkarni R, Behme RJ, Kotiyan PN. Effect of the melt granulation technique on the dissolution characteristics of griseofulvin. Int. J. Pharm. 2007;329:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarode AL, Sandhu H, Shah N, Malick W, Zia H. Hot melt extrusion (HME) for amorphous solid dispersions: predictive tools for processing and impact of drug–polymer interactions on supersaturation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;48:371–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breitenbach J. Melt extrusion: from process to drug delivery technology. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2002;54:107–17. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(02)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qian F, Huang J, Hussain MA. Drug–polymer solubility and miscibility: stability consideration and practical challenges in amorphous solid dispersion development. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99:2941–7. doi: 10.1002/jps.22074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fitzpatrick S, McCabe JF, Petts CR, Booth SW. Effect of moisture on polyvinylpyrrolidone in accelerated stability testing. Int. J. Pharm. 2002;246:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alsulays BB, Park JB, Alshehri SM, Morott JT, Alshahrani SM, Tiwari RV, Repka MA. Influence of molecular weight of carriers and processing parameters on the extrudability, drug release, and stability of fenofibrate formulations processed by hot-melt extrusion. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2015;29:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patil H, Tiwari RV, Repka MA. Hot-Melt Extrusion: from Theory to Application in Pharmaceutical Formulation. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2015:1–23. doi: 10.1208/s12249-015-0360-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maddineni S, Battu SK, Morott J, Majumdar S, Murthy SN, Repka MA. Influence of Process and Formulation Parameters on Dissolution and Stability Characteristics of Kollidon® VA 64 Hot-Melt Extrudates. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2015;16(2):444–454. doi: 10.1208/s12249-014-0226-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mididoddi PK, Repka MA. Characterization of hot-melt extruded drug delivery systems for onychomycosis. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2007;66(1):95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forster A, Hempenstall J, Tucker I, Rades T. Selection of excipients for melt extrusion with two poorly water-soluble drugs by solubility parameter calculation and thermal analysis. Int. J. Pharm. 2001;226(1):147–161. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]