Summary

The tafazzin (TAZ) gene is highly conserved from yeast to humans, and the yeast taz1 null mutant shows alterations in cardiolipin (CL) metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction and stabilization of supercomplexes similar to those found in Barth syndrome, a human disorder resulting from loss of tafazzin. We have previously shown that the yeast tafazzin mutant taz1Δ, which cannot remodel CL, is ethanol-sensitive at elevated temperature. In the current report, we show that in response to ethanol, CL mutants taz1Δ as well as crd1Δ, which cannot synthesize CL, exhibited increased protein carbonylation, an indicator of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The increase in ROS is most likely not due to defective oxidant defence systems, as the CL mutants do not display sensitivity to paraquat, menadione or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Ethanol sensitivity and increased protein carbonylation in the taz1Δ mutant but not in crd1Δ can be rescued by supplementation with oleic acid, suggesting that oleoyl-CL and/or oleoyl-monolyso-CL enables growth of taz1Δ in ethanol by decreasing oxidative stress. Our findings of increased oxidative stress in the taz1Δ mutant during respiratory growth may have important implications for understanding the pathogenesis of Barth syndrome.

Introduction

Barth syndrome (BTHS) is a severe X-linked inherited disorder characterized by short stature, cardioskeletal myopathy, neutropenia, abnormal mitochondria and respiratory chain dysfunction (Barth et al., 1999). The disease is caused by mutations in the tafazzin (TAZ) gene G4.5 (Bolhuis et al., 1991; Bione et al., 1996). Tafazzin is a phospholipid acyltransferase that has been shown to remodel cardiolipin (CL) (Neuwald, 1997), the signature lipid of the mitochondrial inner membrane. As a result, BTHS patients exhibit defects in CL metabolism, including aberrant CL fatty acyl composition, accumulation of monolysocardiolipin (MLCL) and reduced total CL levels (Vreken et al., 2000; Valianpour et al., 2005). How these metabolic defects lead to the variety of symptoms characteristic of BTHS is not understood.

The TAZ gene is highly conserved from yeast to humans. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene YPR140w (TAZ1) is homologous to the human TAZ gene, and the yeast taz1 null mutant shows alterations in CL metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction similar to those found in BTHS patients (Vaz et al., 2003; Gu et al., 2004; Ma et al., 2004). Therefore, elucidating mechanisms underlying defects associated with tafazzin deficiency in the yeast model is expected to shed light on BTHS. The TAZ1 gene is essential for growth of yeast in ethanol at elevated temperature, and loss of tafazzin leads to ethanol sensitivity. Ethanol is a powerful inhibitor of the growth, viability and fermentation rate of yeast cells (Brown et al., 1981; Jones and Greenfield, 1985). A proposed target of ethanol damage is the mitochondrion, as ethanol causes loss of mitochondrial DNA and inactivation of some mitochondrial enzymes (Jimenez and Benitez, 1988; Jimenez et al., 1988; Ibeas and Jimenez, 1997). Increasing evidence suggests that ethanol toxicity is correlated with the production of acetaldehyde and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the mitochondria during ethanol metabolism (Costa et al., 1997; Du and Takagi, 2007). Ethanol is preferentially oxidized to acetaldehyde by cytosolic alcohol dehydrogenase, forming NADH in the process (Wills, 1990). The NADH is then utilized to synthesize ATP by the mitochondrial electron transport chain, which is the main endogenous source of ROS.

Reactive oxygen species are potentially toxic by-products of oxygen metabolism in aerobic organisms. The reaction of ROS with cellular components, including lipids, proteins and nucleic acids, leads to loss of function and cell death. Excess ROS is associated with a variety of diseases and with the process of ageing (Ames et al., 1993; Shigenaga et al., 1994; Costa and Moradas-Ferreira, 2001). Under normal physiological conditions, cells contain antioxidant defence mechanisms to protect against the toxic effects of ROS, including catalase, glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase (SOD), and non-enzymic molecules such as glutathione (Jamieson, 1998). However, during some stress conditions, the levels of ROS exceed the antioxidant capacity of the cell, resulting in oxidative damage. In yeast, the major site of intracellular ROS generation is the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Several mitochondrial respiratory complexes and individual enzymes (NADH dehydrogenase, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) have been identified as sources of ROS (Turrens, 2003), and complex III is considered to be the principal site of ROS generation (Chance et al., 1979; Chen et al., 2003). In the yeast S. cerevisiae, normal mitochondrial function is required for resistance to oxidative stress (Grant et al., 1997), and the maintenance of a stable respiratory chain strongly prevents the generation of mitochondrial ROS (Barros et al., 2003).

Cardiolipin, an anionic phospholipid in the mitochondrial inner membrane, plays an important role in the stabilization of electron transport chain complexes. The interactions of CL with membrane proteins are required for optimal function (Hoch, 1992; Schlame et al., 2000). CL has been found to bind to inner membrane proteins, such as the ADP/ATP carrier, complex III and complex IV (Yu and Yu, 1980; Drees and Beyer, 1988; Robinson et al., 1990; Schagger et al., 1990; Hayer-Hartl et al., 1992; Beyer and Nuscher, 1996; Gomez and Robinson, 1999; Sedlak and Robinson, 1999). CL binding is essential for the optimal function of mitochondrial enzymes and for supercomplex stability. In yeast, CL synthase mutant cells (crd1Δ), which lack CL, exhibit decreased stability of supercomplexes (Zhang et al., 2002; Pfeiffer et al., 2003). Similarly, mitochondrial supercomplex stability is also decreased in BTHS patients and in the yeast taz1Δ mutant (Brandner et al., 2005; McKenzie et al., 2006). Phospholipid analysis of cells of BTHS patients and the yeast taz1Δ mutant shows reduced CL and altered CL acyl composition (Vreken et al., 2000; Schlame et al., 2003; Vaz et al., 2003; Gu et al., 2004). In the yeast taz1Δ mutant, CL defects result in dissociation of supercomplex III2IV2, releasing a complex IV monomer (Brandner et al., 2005). Similar to yeast taz1Δ cells, lymphoblasts from BTHS patients exhibit destabilization of the supercomplex by weakening the interactions between complexes I, III and IV (McKenzie et al., 2006). This suggests that reduced levels and/or altered fatty acyl incorporation in CL leads to destabilization of the mitochondrial supercomplex, which may account for the mitochondrial dysfunction observed in the yeast taz1Δ mutant and in BTHS patients (Ma et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2005).

Because CL mutants exhibit electron transport chain defects and supercomplex instability, we hypothesized that CL mutant cells produce excessive ROS in the presence of ethanol. Consistent with the hypothesis, we found that crd1Δ and taz1Δ mutants exhibited increased protein carbonylation, an indicator of ROS, in response to ethanol. The excessive production of ROS is most likely not due to defective oxidant defence systems, as the CL mutants do not display sensitivity to paraquat, menadione or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Ethanol sensitivity and increased protein carbonylation in the taz1Δ mutant but not in crd1Δ can be rescued by supplementation with oleic acid (C18:1), suggesting that oleoyl CL/MLCL enables growth of taz1Δ in ethanol by decreasing oxidative stress. These findings suggest that the loss of tafazzin leads to chronic and excessive ROS accumulation, which may contribute to cell or tissue damage.

Results

The taz1Δ mutant exhibits increased protein carbonylation during growth in ethanol at elevated temperature

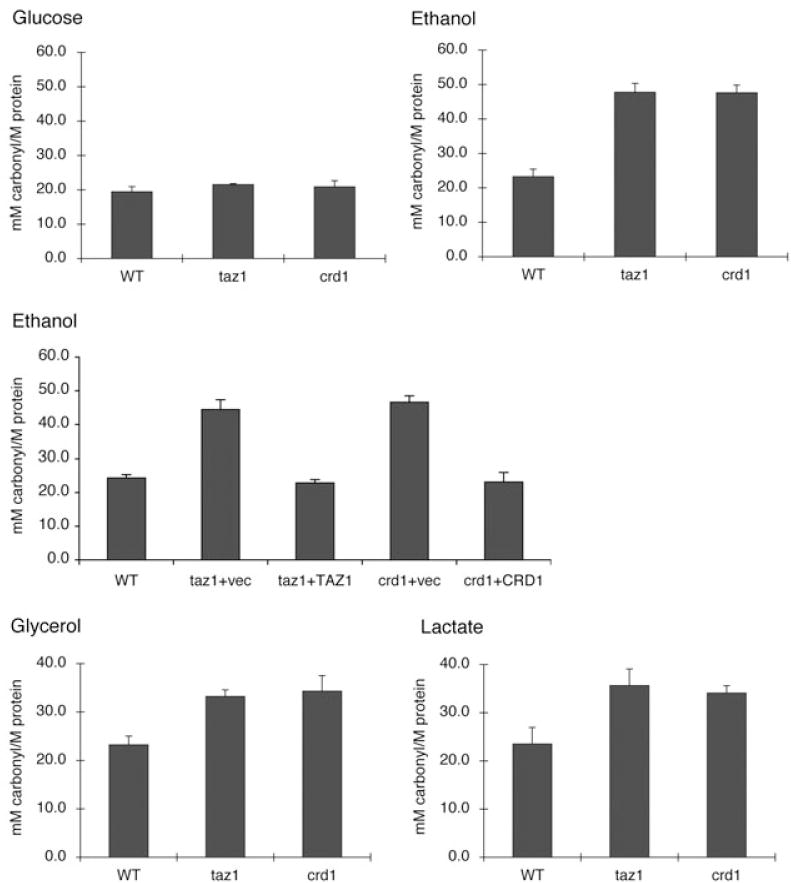

We showed previously that during growth in ethanol as a sole carbon source, the yeast taz1Δ mutant exhibited decreased growth at elevated temperature (Gu et al., 2004), similar to the crd1Δ mutant, which lacks CL synthase and has no detectable CL (Jiang et al., 1997; Chang et al., 1998). Yeast cells grown in aerobic conditions are continuously exposed to ROS generated during oxygen consumption. Under normal conditions, cells use antioxidant defence mechanisms to prevent ROS build-up, maintaining low levels of ROS. However, under some conditions, the levels of ROS exceed the antioxidant capacity, and cells face oxidative stress (Costa and Moradas-Ferreira, 2001). Ethanol has been associated with ROS production in yeast (Jimenez and Benitez, 1988; Costa et al., 1993; Costa et al., 1997; Bailey et al., 1999; Quintans et al., 2005; Du and Takagi, 2007). Therefore, a possible explanation for the growth defect of the taz1Δ mutant in ethanol is that the mutant is subject to increased oxidative stress. To examine this possibility, we measured cellular protein carbonylation, which is a sensitive indicator of oxidative stress (Reznick and Packer, 1994). Carbonyl groups (aldehydes or ketones) result from the oxidation of acids and serve as markers for protein oxidation (Dirmeier et al., 2004). As shown in Fig. 1, the level of protein carbonylation in taz1Δ and crd1Δ is double that of wild-type cells in media containing ethanol, while in glucose media, protein carbonylation levels are not affected. This suggests that taz1Δ and crd1Δ mutants are subject to oxidative stress when cultured in media containing ethanol at high temperature. When transformed with a plasmid-borne copy of the TAZ1 or CRD1 gene, the taz1Δ and crd1Δ mutants, respectively, did not show increased protein carbonylation.

Fig. 1.

CL mutants exhibit increased protein carbonylation in response to non-fermetable carbon source at 37°C. Cells were grown at 37°C to the early stationary phase in glucose (2%), ethanol (0.75%), glycerol (3%) or lactate (2%) as indicated. Protein was extracted and protein carbonylation was measured as described under Experimental procedures. Data represent the average of three independent experiments.

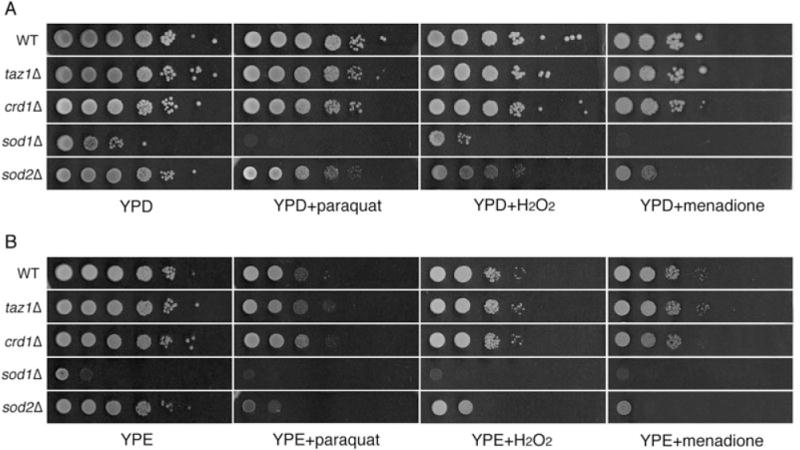

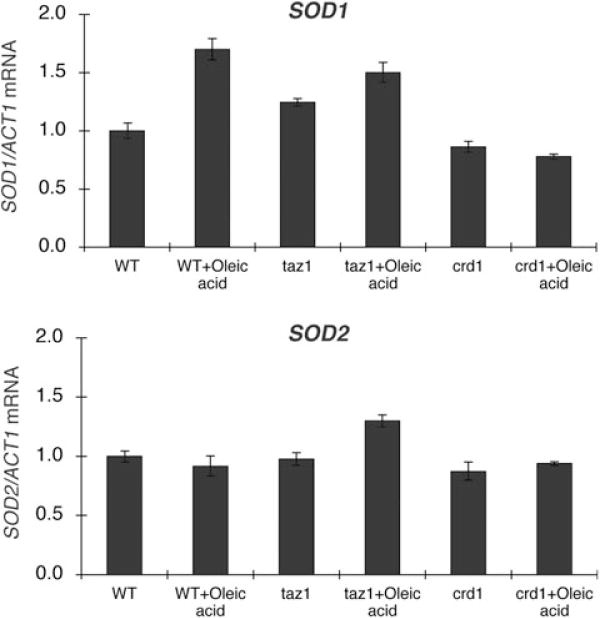

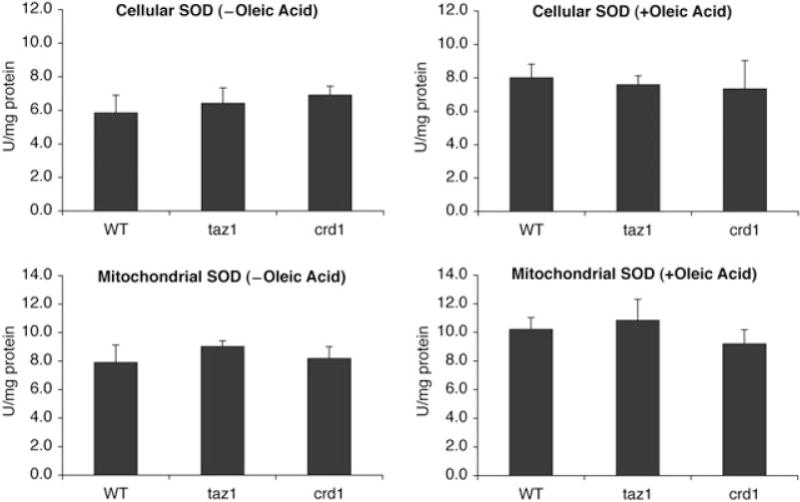

To determine whether increased protein carbonylation in taz1Δ and crd1Δ resulted from defective antioxidant defence against oxidative stress versus excessive generation of ROS, we examined taz1Δ and crd1Δ cells for sensitivity to other ROS-generating agents, including paraquat, menadione and H2O2. As shown in Fig. 2, taz1Δ and crd1Δ mutants were not sensitive to paraquat, menadione or H2O2, in contrast to sod1Δ and sod2Δ mutants, which cannot detoxify ROS. This suggests that the antioxidant defences of taz1Δ and crd1Δ are not defective. Consistent with this, the expression of SOD1 and SOD2 mRNAs (Fig. 3) and cellular and mitochondrial SOD activities (Fig. 4) were not affected in taz1Δ and crd1Δ in response to ethanol. Therefore, the increased protein carbonylation levels in taz1Δ and crd1Δ mutants during growth in ethanol are most likely due to excessive ROS generation. These results imply that growth in media with ethanol as carbon source leads to ROS overproduction in CL mutants, which exceeds the antioxidant capacity and causes defective growth. During growth on other non-fermentable carbon sources, including glycerol and lactate, we observed similar growth defects and increased protein carbonylation in the crd1Δ and taz1Δ mutants (Fig. 1). Therefore, increased oxidative stress occurs in CL mutant cells during respiratory growth conditions, but not during fermentative growth on glucose (or in the presence of ethanol when glucose is also present).

Fig. 2.

CL mutants are not sensitive to paraquat, menadione or H2O2. Cells were cultured at 30°C in rich media to the early stationary phase, serially diluted and spotted on YPD (A) and YPE (1% ethanol) (B) plates supplemented with 0.5 mM paraquat, 0.1 mM menadione or 2.5 mM H2O2. The plates were incubated at 37°C. While crd1Δ and taz1Δ cells are sensitive to 1% ethanol in liquid media, sensitivity on solid media is detectable at concentrations greater than 2%.

Fig. 3.

SOD1 and SOD2 expression in CL mutants. Cells were grown in YPE (0.75% ethanol) plus or minus 1 mM oleic acid at 37°C to the early stationary phase. Total RNA was extracted, and SOD1 and SOD2 mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR as described under Experimental procedures. The expression of SOD1 and SOD2 was normalized to the RNA levels of the internal control ACT1. Data are the average of three independent experiments.

Fig. 4.

Activities of SOD in CL mutants at 37°C. Cells were grown in YPE (0.75% ethanol) plus or minus 1 mM oleic acid at 37°C to the early stationary phase. Activities of cellular and mitochondrial SOD were determined using cell lysate or mitochondrial extract respectively. Data represent the average of three independent experiments.

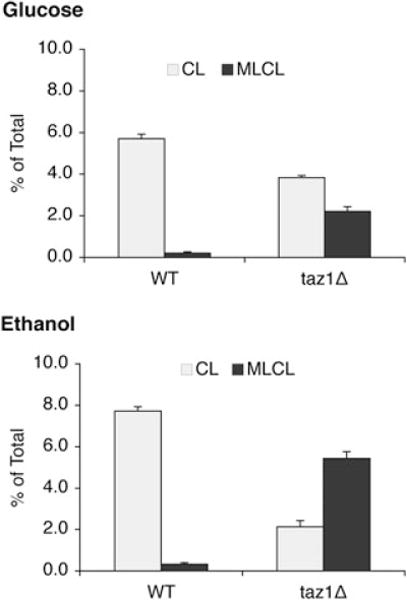

The taz1Δ mutant exhibits increased MLCL and decreased CL in response to ethanol

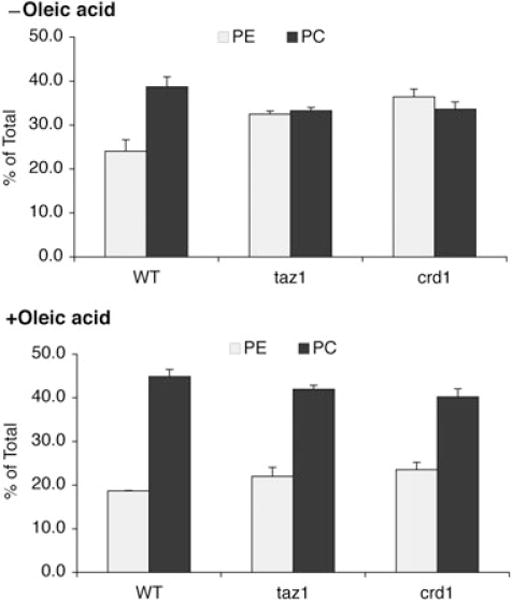

We wished to determine if increased protein carbonylation and ethanol sensitivity of the taz1Δ mutant are correlated with aberrant remodelling of CL. We therefore examined the steady-state CL/MLCL levels in the taz1Δ mutant. In media containing glucose as the carbon source, the CL level in taz1Δ was 30% less than that of the wild type, and the MLCL level was increased by 10-fold (Fig. 5). Despite these perturbations of CL levels, the taz1Δ mutant did not show decreased growth in glucose (data not shown). In media with ethanol as the sole carbon source, CL levels were reduced by about 70%, and MLCL was increased by 17-fold (Fig. 5). Abnormalities were also seen in phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and phosphatidylcholine (PC) composition. Similar to crd1Δ, the taz1Δ mutant showed increased PE and reduced PC in response to ethanol (Fig. 6, oleic acid). These findings are consistent with the study of Chi and Arneborg (1999), who reported that ethanol sensitivity was associated with decreased CL and PC levels. These results suggest that PE and PC levels are co-ordinately regulated with CL synthesis and remodelling.

Fig. 5.

The taz1Δ mutant exhibits increased MLCL and decreased CL in response to ethanol. Cells were grown in YPD or YPE (0.75% ethanol) at 37°C to the early stationary phase. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and lipids were extracted and separated as described in Experimental procedures. Phospholipids were separated by one-dimensional TLC and visualized by phosphorimaging. CL and MLCL were quantified using ImageQuant software. The relative amount of 32P in CL and MLCL is presented as a percentage of the 32P incorporated into total phospholipids. Data represent the average of three independent experiments.

Fig. 6.

Supplementation with oleic acid restores PE and PC in CL mutants to wild-type levels. Cells were grown in YPE (0.75% ethanol) plus or minus 1 mM oleic acid at 37°C to the early stationary phase. Phospholipids were extracted and quantified as described in the legend for Fig. 5. Data represent the average of three independent experiments.

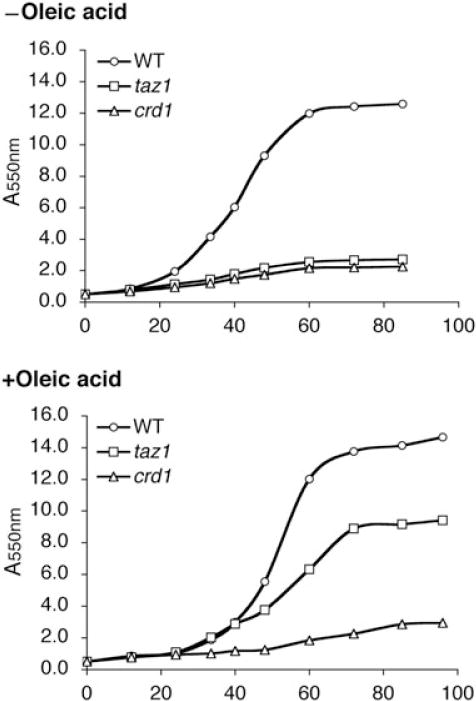

Ethanol sensitivity of the taz1Δ mutant is rescued by supplementation with oleic acid

Yeast CL has a unique fatty acid composition compared with other mitochondrial phospholipids. It is mainly composed of mono-unsaturated acyl chains of 16–18 carbons in length, such as palmitic acid (C16:0), palmitoleic acid (C16:1), stearic acid (C18:0) and oleic acid (C18:1). Of these, oleic acid and palmitoleic acid are predominant in CL, resulting in a much higher unsaturation index than in other phospholipids. Several studies have documented the alteration of cellular phospholipid composition in response to ethanol exposure (Mishra and Prasad, 1988; Chi and Arneborg, 1999). The degree of fatty acid unsaturation is thought to play a major role in the ethanol sensitivity of yeast (Tuller et al., 1999; You et al., 2003). Consistent with this hypothesis, the taz1Δ mutant exhibits a marked decrease in CL molecular species containing unsaturated fatty acids (Gu et al., 2004). We wished to determine if fatty acids with a greater degree of unsaturation could support growth of the mutants in ethanol. To this end, we examined the effect of supplementation of different fatty acids on growth of the taz1Δ mutant. In the presence of 1 mM oleic acid (C18:1), growth of taz1Δ was significantly improved in YPE media at 37°C (Fig. 7). In contrast to oleic acid, supplementation with the other fatty acids tested (C18:0, C16:1 and C16:0) did not alleviate ethanol sensitivity of the taz1Δ mutant (data not shown). Oleic acid did not rescue the growth defect of crd1Δ, which lacks CL and MLCL, suggesting that unsaturated CL or MLCL species are required to alleviate the ethanol sensitivity of taz1Δ.

Fig. 7.

Supplementation of oleic acid rescues ethanol sensitivity of the taz1Δ mutant at 37°C. Cells were grown in YPE (1% ethanol) plus or minus 1 mM oleic acid at 37°C. Cell growth was monitored by A550 at the indicated times.

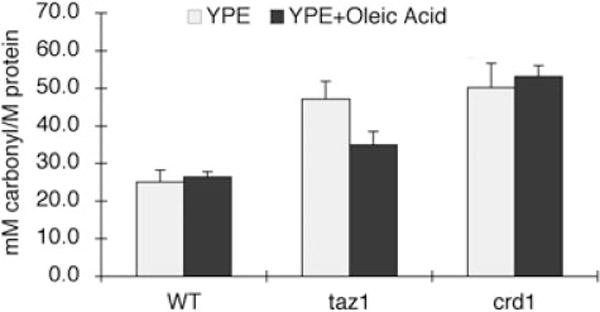

We analysed the phospholipids of wild type and taz1Δ cells using one-dimensional thin-layer chromatography (TLC) to determine whether phospholipid levels were affected by supplementation with oleic acid. As shown in Fig. 8A, supplementation with oleic acid did not affect CL or MLCL levels in the taz1Δ mutant. In cells supplemented with oleic acid, CL and MLCL migrated faster than those lipids from cells cultured without oleic acid (Fig. 8B), consistent with incorporation of oleic acid into the lipids. The migration of other phospholipids was also slightly increased. Interestingly, supplementation of oleic acid restored PC and PE levels in the taz1Δ mutant to those of wild-type cells (Fig. 6, +oleic acid), which is consistent with previous reports that PE levels and the PE/PC ratio tend to decrease when yeast is supplemented with unsaturated fatty acids of longer chain length and higher degree of unsaturation (Pilkington and Rose, 1991; de Kroon, 2007). None of the other fatty acids, including palmitic acid, palmitoleic acid and stearic acid, restored PC and PE levels or growth on ethanol (data not shown). These results suggest that the steady-state levels of PE and PC in the taz1Δ mutant are regulated by fatty acid composition of CL/MLCL. However, the presence of wild-type levels of PC and PE are not sufficient to alleviate ethanol sensitivity, as restoration of PC and PE levels in the crd1Δ mutant did not lead to growth in ethanol (Figs 6 and 7). These findings suggest that the presence of CL or MLCL is necessary for growth in ethanol. If oleoyl CL/MLCL enabled growth in ethanol by reducing the generation of ROS, we would expect that protein carbonylation would be decreased in taz1Δ, but not crd1Δ cells supplemented with oleic acid. Consistent with this, in the presence of oleic acid, the protein carbonylation level was decreased by 25% in taz1Δ, but not in crd1Δ (Fig. 9). This suggests that oleoyl CL/MLCL enables growth of taz1Δ in ethanol by decreasing oxidative stress.

Fig. 8.

Supplementation of oleic acid affects migration of CL and MLCL on TLC.

A. Cells were grown in YPE (0.75% ethanol) plus or minus 1 mM oleic acid. Phospholipid levels were quantified as described in Fig. 5.

B. Analysis of phospholipids by one-dimensional TLC identifies altered migration of CL and MLCL in the presence of oleic acid. Data represent the average of three independent experiments.

Fig. 9.

Supplementation with oleic acid partially rescues accumulation of protein carbonylation in the taz1Δ mutant. Cells were grown in YPE (0.75% ethanol) plus or minus 1 mM oleic acid at 37°C to the early stationary phase. Protein was extracted and protein carbonylation was measured as described under Experimental procedures. Data represent the average of three independent experiments.

Discussion

In this study, we addressed the hypothesis that the taz1Δ mutant produces excessive ROS in response to ethanol, resulting in ethanol sensitivity. Consistent with the hypothesis, we showed that: (i) the taz1Δ and crd1Δ mutants exhibit increased protein carbonylation in the presence of ethanol, which most likely cannot be attributed to a defective oxidant defence system and (ii) ethanol sensitivity and ROS production in taz1Δ, but not crd1Δ, can be alleviated by supplementation with oleic acid, suggesting that CL/MLCL plays an important role in modulating oxidative stress during respiration.

In yeast, ethanol sensitivity is correlated with the production of ROS (Costa et al., 1997; Du and Takagi, 2007), which is produced primarily in the mitochondrial respiratory chain (Chance et al., 1979; Chen et al., 2003; Turrens, 2003). CL plays multiple roles in mitochondrial structure and function. The increased oxidative stress on CL mutants shown here reflects the importance of CL in mitochondrial function. The interactions between CL and mitochondrial membrane proteins are important for the stabilization and optimal functions of these proteins, including those that comprise the supercomplexes in the respiratory chain (Schlame et al., 2000). Consistent with this, the loss of CL (in crd1Δ) or aberrant remodelling of CL (in taz1Δ) leads to destabilization of respiratory chain supercomplexes (Brandner et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005). Complex IV is dissociated from complex III in crd1Δ and taz1Δ mutants. (Zhang et al., 2002; Pfeiffer et al., 2003; Brandner et al., 2005). Mitochondrial complex III is the major source of superoxide in mitochondria (Chance et al., 1979; Chen et al., 2003). The redox centres of complex III may leak electrons to oxygen, constituting the primary source of superoxide anion (Turrens, 2003). It is likely that the observed increased protein carbonylation in crd1Δ and taz1Δ in response to ethanol consumption (Fig. 1) stems from the destabilization of the respiratory complexes. Increased protein carbonylation was also seen during respiration in the presence of other respiratory carbon sources, including glycerol and lactate (Fig. 1), indicating that oxidative stress is not limited to growth in ethanol, but rather is a by-product of respiration in the absence of CL. An alternative explanation that the CL mutants have defective antioxidant defence mechanisms is unlikely for several reasons. First, CL mutants are not sensitive to paraquat, menadione or H2O2 (Fig. 2). Second, SOD is the major ROS scavenger in ethanol tolerance and respiratory growth (Costa et al., 1993; Costa et al., 1997; Lushchak et al., 2005). CL mutants did not exhibit altered expression of SOD1 and SOD2 (Fig. 3) or decreased cellular or mitochondrial SOD activities (Fig. 4). Stabilization of complex III2IV2 by CL/MLCL may play an important role in transporting electrons along protein complexes to the ultimate acceptors, and prevent leakage of electrons from the respiratory chain. The results presented here are consistent with studies linking functional mitochondria to resistance to oxidative stress (Grant et al., 1997; Barros et al., 2003).

Our finding that oleic acid rescues increased protein carbonylation and ethanol sensitivity in the taz1Δ mutant, which contains MLCL and CL, but not in the crd1Δ mutant, which lacks both of these lipids, suggests that CL and/or MLCL plays a key role in modulating oxidative stress during respiration. These results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated a relationship between lipid composition and ethanol sensitivity. Ethanol-tolerant yeast strains contain a higher CL content and a higher proportion of oleoyl species (C18:1) compared with ethanol-sensitive strains (Chi and Arneborg, 1999). Oleic acid (C18:1) was the most effective fatty acid in overcoming ethanol toxicity, while palmitoleic acid (C16:1) did not confer ethanol tolerance (You et al., 2003). When yeast cells were shifted from glucose to ethanol as the carbon source, incorporation of C18:1 into the plasma and mitochondrial membranes increased significantly while incorporation of C16:0 into the phospholipids decreased, and there was no significant difference in C16:1 and C18:0 incorporation (Tuller et al., 1999). The abundance of (C18:1)4-CL and (C18:1)3-(C16:1)1-CL comprises more than 70% of total CL species (Schlame et al., 2005). In contrast, the taz1Δ mutant contains markedly decreased (five- to sixfold) (C18:1)4-CL and (C18:1)3-(C16:1)1-CL, while (16:1)4-CL is increased (fourfold) (Valianpour et al., 2001). In the current study, CL levels were reduced by 70% in the taz1Δ mutant during growth in ethanol versus glucose (Fig. 5), and supplementation with C18:1 in the growth media rescued ethanol sensitivity. Supplementation with oleic acid also alleviated protein carbonylation in the taz1Δ mutant. These results indicate that the fatty acid species composition of phospholipids, especially the incorporation of oleic acid, plays an important role in the maintenance of functional mitochondria during ethanol stress. The effect of oleic acid on ethanol sensitivity and protein carbonylation is CL- and/or MLCL-dependent, as ethanol sensitivity and protein carbonylation in the CL-lacking mutant crd1Δ cannot be rescued by supplementation with oleic acid. The inability of other fatty acids to rescue ethanol sensitivity suggests that C18:1 species of CL/MLCL are required to lower oxidative stress. The observation that taz1Δ, which lacks CL remodelling capability, may incorporate exogenous fatty acids into CL/MLCL suggests that substrate specificity by enzymes that contribute to CL synthesis plays a role in determining the acyl species of CL.

In summary, we have shown that the loss of tafazzin in yeast leads to increased oxidative stress during respiratory growth at high temperature. The yeast taz1Δ mutant has been shown to be a good genetic/biochemical model for BTHS. Similar to BTHS cells, taz1Δ mutant cells exhibit increased MLCL, decreased CL and aberrant fatty acyl species of this lipid (Gu et al., 2004). Mitochondria from the taz1Δ mutant exhibit decreased coupling and destabilization of supercomplexes (Ma et al., 2004; Brandner et al., 2005). Our findings of increased oxidative stress in the taz1Δ mutant during respiratory growth may have important implications for understanding the pathogenesis of BTHS.

Experimental procedures

Yeast strains and growth media

The S. cerevisiae strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Synthetic complete medium contained adenine (20.25 mg l−1), arginine (20 mg l−1), histidine (20 mg l−1), leucine (60 mg l−1), lysine (200 mg l−1), methionine (20 mg l−1), threonine (300 mg l−1), tryptophan (20 mg l−1), uracil (20 mg l−1), yeast nitrogen base w/o amino acids (Difco) and glucose (2%) (SD). Synthetic drop-out medium (Leu-) contained all of the above ingredients except leucine. Complex media contained yeast extract (1%), peptone (2%) and glucose (2%) (YPD), ethanol (0.5–1.0%) (YPE), glycerol (3%) (YPG) or lactate (2%) (YPL). YPE/FA was YPE supplemented with specific fatty acids, 1.0 mM oleic acid, 1.0 mM palmitoleic acid, 1.0 mM palmitic acid or 1.0 mM stearic acid. Fatty acids were prepared as 1 M stock solutions in 100% ethanol. In the media, fatty acids were solubilzied with Tergitol (1%). The solid medium contained agar (2%) in addition to the above-mentioned ingredients.

Table 1.

Plasmids and yeast strains used in this study.

| Plasmid/strains | Characteristics or genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pYPGK18 | 2 μm, LEU2 | Vaz et al., 2003) |

| pYPGK18CRD1 | Derivative of pYPGK18, expresses CRD1 from PGK1 promoter | This study |

| pTAZ1 | Derivative of pYPGK18, expresses TAZ1 from PGK1 promoter | Vaz et al. (2003) |

| FGY3 | MAT α, ura 3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, trp1Δ1, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1 | Jiang et al. (1997) |

| FGY2 | MAT α, ura 3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, trp1Δ1, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, crd1Δ∷URA3 | Jiang et al. (1997) |

| ZGY1 | MAT α, ura 3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, trp1Δ1, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, taz1Δ∷KanMX4 | Ma et al. (2004) |

| FGY3 sod1Δ | MAT α, ura 3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, trp1Δ1, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, sod1Δ∷KanMX4 | This study |

| FGY3 sod2Δ | MAT α, ura 3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, trp1Δ1, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, sod2Δ∷KanMX4 | This study |

The sod1Δ and sod2Δ mutants were constructed as follows. The entire open reading frame of the SOD1 or SOD2 gene was replaced by KanMX4 using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-mediated homologous recombination in the FGY3 wild-type strain. The KanMX4 cassette was amplified from pUG6 using primers consisting of 50 nucleotides identical to the SOD1 or SOD2 flanking regions at the 5′ end and 21 nucleotides for the amplification of the KanMX4 gene at the 3′ end. The PCR product was transformed into FGY3, and transformants were selected on YPD media containing G418. Disruption of SOD1 and SOD2 was confirmed by the absence of the target PCR product using primers against the SOD1 and SOD2 coding sequences respectively.

Plasmid construction

A 1525 bp CRD1 sequence containing promoter and coding sequences was amplified from yeast genomic DNA using BamHI-tagged primer CRD15′ (5′-GGATCCATGCTTAACTGATCCTGGCGT-3′) and ClaI-tagged primer CRD13′ (5′ ATCGATGCATTCAGCCGTTAACATGG-3′). The PCR reaction products were cloned into the pRS200 vector. The resulting recombinant plasmid, pRS200-CRD1, was digested with MfeI and SalI. The pYPGK18 vector was digested with EcoRI and SalI. The DNA fragment containing CRD1 was cloned into the pYPGK18 vector, downstream of the yeast PGK1 promoter.

Growth conditions

For ethanol sensitivity studies, cultures were started by inoculating 10 ml of YPE liquid medium to a cell density of A550 = 0.5. Cultures were agitated at 250 r.p.m. at 30°C or 37°C, and growth was followed by measuring A550. For paraquat, menadione and H2O2 sensitivity studies, yeast cells were grown in YPD media at 30°C to the early stationary phase. Cultures were then serially diluted and spotted onto YPD or YPE plates with added paraquat (0.5 mM), menadione (0.1 mM) or H2O2 (2.5 mM) and incubated for 3–5 days at 37°C.

Superoxide dismutase activity assay

Activities of SOD were determined using the Bioxytech SOD-525 kit (Oxis Health Products). Cell lysate (4 mg protein) in 0.9% NaCl was centrifuged at 10 000 r.p.m. for 60 min in a microcentrifuge at 0°C and the supernatant was used to determine the activity of cytosolic SOD activity. Mitochondrial SOD activity was assayed in mitochondrial extracts. Isolation of mitochondria was performed as previously described (Koshkin and Greenberg, 2000). The assay method is based on the SOD-mediated increase in the rate of autoxidation of 5,6,6a,11b-tetrahydro-3,9,10-trihydroxybenzofluorene as a substrate in aqueous alkaline solution to yield a chromophore with maximum absorbance at 525 nm (Nebot et al., 1993).

Quantification of protein carbonyl content

The content of carbonyl groups in proteins was measured by determining the amount of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone (DNP) formed upon reaction with 2,4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine (DNPH). The protein carbonyl content was measured as described with minor modifications (Reznick and Packer, 1994; Dirmeier et al., 2004). Yeast cells were grown at 37°C to the early stationary phase in glucose or ethanol. Harvested cells were subjected to mechanical breakage with glass beads. Cell extracts were separated from glass beads and cells by centrifugation, and nucleic acids were removed from the cell extracts with 1.0% streptomycin sulphate. The resulting protein samples (> 1.5 mg protein) were incubated with 10 mM DNPH in 2 M HCl at room temperature for 60 min in the dark. Proteins were precipitated by addition of trichloroacetic acid to a final concentration of 10%, and the pellets were washed with ethanol : ethyl acetate (1:1) to remove the free DNPH. The final protein pellets were dissolved in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride solution containing 20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 2.4. The carbonyl content was calculated from the absorbance maximum of DNP measured at 370 nm.

Phospholipid determination

Yeast cells were grown in the presence of 32Pi (10 μCi ml−1) at 30°C or 37°C to the early stationary phase. Cells were then washed and digested by zymolyase to yield spheroplasts. Total lipids were extracted from spheroplasts with chloroform : methanol (2:1) (v/v). The extracted lipids were applied to a boric acid-treated TLC plate, which was developed in the one-dimensional solvent system chloroform/triethylamine/ethanol/water (30:35:35:7). Developed chromatograms were quantified by phosphorimaging (Vaden et al., 2005).

Real-time PCR

Yeast cultures (10 ml) were grown to the early stationary phase, cells were harvested and total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). The RNA samples were treated with DNase from a DNA-free Kit (Ambion) to remove contaminating genomic DNA. cDNAs were synthesized with a Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR reactions were performed in a 50 μl volume using Brilliant SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene) in a 96-well plate. Duplicates for each sample were included for each reaction. The real-time PCR primers used in this work are listed in Table 2. ACT1 was used as the internal control and the RNA level of the gene of interest was normalized to ACT1 levels. PCR reactions were initiated at 95°C for 10 min for denaturation followed by 40 cycles consisting of 30 s at 95°C and 60 s at 57°C.

Table 2.

The real-time PCR primers used in this study.

| Gene | Primers | Sequence | Product length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACT1 | Forward | TCGTGCTGTCTTCCCATCTATCG | 218 |

| Reverse | CGAATTGAGAGTTGCCCCAGAAG | ||

| SOD1 | Forward | TAACGCAGAACGTGGGTTCC | 314 |

| Reverse | CTGGTAATGCCGGTCCAAGAC | ||

| SOD2 | Forward | CACAGCAAGGAGAACCAAAGTCAC | 374 |

| Reverse | ACTTAATCAGCTCGTCCAGACTGC |

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Zhiming Gu for helping to initiate this study and for valuable discussion, and Dr Quan Zhong, Dr Vishal Gohil and Rania Deranieh for helpful advice. This work was supported by a grant from the Barth Syndrome Foundation and by Grant HL62263 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7915–7922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SM, Pietsch EC, Cunningham CC. Ethanol stimulates the production of reactive oxygen species at mitochondrial complexes I and III. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:891–900. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros MH, Netto LE, Kowaltowski AJ. H(2)O(2) generation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae respiratory pet mutants: effect of cytochrome c. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth PG, Wanders RJ, Vreken P. X-linked cardioskeletal myopathy and neutropenia (Barth syndrome)-MIM 302060. J Pediatr. 1999;135:273–276. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer K, Nuscher B. Specific cardiolipin binding interferes with labeling of sulfhydryl residues in the adenosine diphosphate/adenosine triphosphate carrier protein from beef heart mitochondria. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15784–15790. doi: 10.1021/bi9610055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bione S, D’Adamo P, Maestrini E, Gedeon AK, Bolhuis PA, Toniolo D. A novel X-linked gene, G4.5. is responsible for Barth syndrome. Nat Genet. 1996;12:385–389. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis PA, Hensels GW, Hulsebos TJ, Baas F, Barth PG. Mapping of the locus for X-linked cardioskeletal myopathy with neutropenia and abnormal mitochondria (Barth syndrome) to Xq28. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:481–485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandner K, Mick DU, Frazier AE, Taylor RD, Meisinger C, Rehling P. Taz1, an outer mitochondrial membrane protein, affects stability and assembly of inner membrane protein complexes: implications for Barth Syndrome. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5202–5214. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SW, Oliver SG, Harrison DEF, Righelato RC. Ethanol inhibition of yeast growth and fermentation: differences in the magnitude and complexity of the effect. Eur J Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1981;11:151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SC, Heacock PN, Mileykovskaya E, Voelker DR, Dowhan W. Isolation and characterization of the gene (CLS1) encoding cardiolipin synthase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14933–14941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: central role of complex III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36027–36031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Z, Arneborg N. Relationship between lipid composition, frequency of ethanol-induced respiratory deficient mutants, and ethanol tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:1047–1052. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa V, Amorim MA, Reis E, Quintanilha A, Moradas-Ferreira P. Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase is essential for ethanol tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the post-diauxic phase. Microbiology (Reading, England) 1997;143:1649–1656. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-5-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa V, Moradas-Ferreira P. Oxidative stress and signal transduction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: insights into ageing, apoptosis and diseases. Mol Aspects Med. 2001;22:217–246. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(01)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa V, Reis E, Quintanilha A, Moradas-Ferreira P. Acquisition of ethanol tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the key role of the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:608–614. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirmeier R, O’Brien K, Engle M, Dodd A, Spears E, Poyton RO. Measurement of oxidative stress in cells exposed to hypoxia and other changes in oxygen concentration. Methods Enzymol. 2004;381:589–603. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)81038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drees M, Beyer K. Interaction of phospholipids with the detergent-solubilized ADP/ATP carrier protein as studied by spin-label electron spin resonance. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8584–8591. doi: 10.1021/bi00423a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Takagi N-Acetyltransferase Mpr1 confers ethanol tolerance on Saccharomyces cerevisiae by reducing reactive oxygen species. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;75:1343–1351. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0940-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez B, Jr, Robinson NC. Phospholipase digestion of bound cardiolipin reversibly inactivates bovine cytochrome bc1. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9031–9038. doi: 10.1021/bi990603r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant CM, MacIver FH, Dawes IW. Mitochondrial function is required for resistance to oxidative stress in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:219–222. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Valianpour F, Chen S, Vaz FM, Hakkaart GA, Wanders RJ, Greenberg ML. Aberrant cardiolipin metabolism in the yeast taz1 mutant: a model for Barth syndrome. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:149–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayer-Hartl M, Schagger H, von Jagow G, Beyer K. Interactions of phospholipids with the mitochondrial cytochrome-c reductase studied by spin-label ESR and NMR spectroscopy. Eur J Biochem. 1992;209:423–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch FL. Cardiolipins and biomembrane function. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 1992;1113:71–133. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(92)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibeas JI, Jimenez J. Mitochondrial DNA loss caused by ethanol in Saccharomyces flor yeasts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:7–12. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.7-12.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson DJ. Oxidative stress responses of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:1511–1527. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199812)14:16<1511::AID-YEA356>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Rizavi HS, Greenberg ML. Cardiolipin is not essential for the growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on fermentable or non-fermentable carbon sources. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:481–491. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5841950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez J, Benitez T. Yeast cell viability under conditions of high temperature and ethanol concentrations depends on the mitochondrial genome. Curr Genet. 1988;13:461–469. doi: 10.1007/BF02427751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez J, Longo E, Benitez T. Induction of petite yeast mutants by membrane-active agents. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:3126–3132. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.12.3126-3132.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RP, Greenfield PF. Replicative inactivation and metabolic inhibition in yeast ethanol fermentations. Biotechnol Lett. 1985;7:223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Koshkin V, Greenberg ML. Oxidative phosphorylation in cardiolipin-lacking yeast mitochondria. Biochem J. 2000;347(Part 3):687–691. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kroon AI. Metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and its implications for lipid acyl chain composition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lushchak V, Semchyshyn H, Mandryk S, Lushchak O. Possible role of superoxide dismutases in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae under respiratory conditions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;441:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Vaz FM, Gu Z, Wanders RJ, Greenberg ML. The human TAZ gene complements mitochondrial dysfunction in the yeast taz1Delta mutant. Implications for Barth syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44394–44399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie M, Lazarou M, Thorburn DR, Ryan MT. Mitochondrial respiratory chain supercomplexes are destabilized in Barth Syndrome patients. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra P, Prasad R. Role of phospholipid head groups in ethanol tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:3205–3211. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-12-3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebot C, Moutet M, Huet P, Xu JZ, Yadan JC, Chaudiere J. Spectrophotometric assay of superoxide dismutase activity based on the activated autoxidation of a tetracyclic catechol. Anal Biochem. 1993;214:442–451. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwald AF. Barth syndrome may be due to an acyltransferase deficiency. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R465–R466. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer K, Gohil V, Stuart RA, Hunte C, Brandt U, Greenberg ML, Schagger H. Cardiolipin stabilizes respiratory chain supercomplexes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52873–52880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington BJ, Rose AH. Incorporation of unsaturated fatty acids by Saccharomyces cerevisiae: conservation of fatty-acyl saturation in phosphatidylinositol. Yeast. 1991;7:489–494. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintans LN, Castro GD, Castro JA. Oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde and free radicals by rat testicular microsomes. Arch Toxicol. 2005;79:25–30. doi: 10.1007/s00204-004-0609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznick AZ, Packer L. Oxidative damage to proteins: spectrophotometric method for carbonyl assay. Methods Enzymol. 1994;233:357–363. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)33041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson NC, Zborowski J, Talbert LH. Cardiolipin-depleted bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase: binding stoichiometry and affinity for cardiolipin derivatives. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8962–8969. doi: 10.1021/bi00490a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schagger H, Hagen T, Roth B, Brandt U, Link TA, von Jagow G. Phospholipid specificity of bovine heart bc1 complex. Eur J Biochem. 1990;190:123–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlame M, Rua D, Greenberg ML. The biosynthesis and functional role of cardiolipin. Prog Lipid Res. 2000;39:257–288. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(00)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlame M, Kelley RI, Feigenbaum A, Towbin JA, Heerdt PM, Schieble T, et al. Phospholipid abnormalities in children with Barth syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1994–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlame M, Ren M, Xu Y, Greenberg ML, Haller I. Molecular symmetry in mitochondrial cardiolipins. Chem Phys Lipids. 2005;138:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak E, Robinson NC. Phospholipase A(2) digestion of cardiolipin bound to bovine cytochrome c oxidase alters both activity and quaternary structure. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14966–14972. doi: 10.1021/bi9914053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN. Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10771–10778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuller G, Nemec T, Hrastnik C, Daum G. Lipid composition of subcellular membranes of an FY1679-derived haploid yeast wild-type strain grown on different carbon sources. Yeast. 1999;15:1555–1564. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199910)15:14<1555::AID-YEA479>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrens JF. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol. 2003;552:335–344. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaden DL, Gohil VM, Gu Z, Greenberg ML. Separation of yeast phospholipids using one-dimensional thin-layer chromatography. Anal Biochem. 2005;338:162–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valianpour F, Vreken P, Nijtmans LG, van Roermund CWT, Grivell LA, Wanders RJ, Barth PG. Investigation of defective cardiolipin remodeling in Barth syndrome using yeast as study model (Abstract) J Inherit Metab Dis. 2001;24:83. [Google Scholar]

- Valianpour F, Mitsakos V, Schlemmer D, Towbin JA, Taylor JM, Ekert PG, et al. Monolysocardiolipins accumulate in Barth syndrome but do not lead to enhanced apoptosis. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1182–1195. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500056-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz FM, Houtkooper RH, Valianpour F, Barth PG, Wanders RJ. Only one splice variant of the human TAZ gene encodes a functional protein with a role in cardiolipin metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43089–43094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305956200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreken P, Valianpour F, Nijtmans LG, Grivell LA, Plecko B, Wanders RJ, Barth PG. Defective remodeling of cardiolipin and phosphatidylglycerol in Barth syndrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:378–382. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills C. Regulation of sugar and ethanol metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;25:245–280. doi: 10.3109/10409239009090611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Sutachan JJ, Plesken H, Kelley RI, Schlame M. Characterization of lymphoblast mitochondria from patients with Barth syndrome. Lab Invest. 2005;85:823–830. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You KM, Rosenfield CL, Knipple DC. Ethanol tolerance in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is dependent on cellular oleic acid content. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:1499–1503. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1499-1503.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CA, Yu L. Structural role of phospholipids in ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase. Biochemistry. 1980;19:5715–5720. doi: 10.1021/bi00566a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Mileykovskaya E, Dowhan W. Gluing the respiratory chain together. Cardiolipin is required for supercomplex formation in the inner mitochondrial membrane. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43553–43556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Mileykovskaya E, Dowhan W. Cardiolipin is essential for organization of complexes III and IV into a supercomplex in intact yeast mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29403–29408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504955200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]