Abstract

The process of ‘becoming’ shapes professionals’ capability, confidence and identity. In contrast to notions of rugged individuals who achieve definitive status as experts, ‘becoming’ is a continuous emergent condition. It is often a process of struggle, and is always interminably linked to its environs and relationships. ‘Becoming’ is a way of understanding the tensions of everyday practice and knowledge of professionals. In this paper, we explore the notion of ‘becoming’ from the perspective of surgeons. We suggest that ‘becoming’, as theorised by Deleuze, offers a more nuanced understanding than is often represented using conventional vocabularies of competence, error, quality and improvement. We develop this conception by drawing from our Deleuze-inspired study of mapping experience in surgery. We argue for Deleuzian mapping as a method to research health professionals’ practice and experience, and suggest the utility of this approach as a pedagogical tool for medical education.

INTRODUCTION

The process through which a professional develops capability, confidence and identity is increasingly described in terms of ‘becoming’.1 In contrast to notions of rugged individuals who achieve definitive status as experts, ‘becoming’ is a continuous emergent condition. It is often a process of struggle, and is always interminably linked to its environs and relationships.

We suggest that this concept may help to unsettle problematically inflated or idealist assumptions about health professionals’ knowledge and capability. In particular, we focus on surgeons. According to their own narratives, surgeons appear to labour under expectations of being ‘super’-men and ‘super’-women. This weighs heavily on some, who feel intimidated by such excessive anticipation of heroic salvation, prevented from displaying weakness or uncertainty, distanced from candid exchanges with their team members and alienated from their own experiences.2 The hero archetype clearly is also inconsistent with directives for collaborative and even coproductive work arrangements with patients and other clinicians.3 Its individualist, hierarchical construction can foreclose analyses that would trace the myriad complex systemic dynamics that affect surgical practice: new technologies, built environments, policies, funding cuts and other social and material elements.

The approach we are taking could be seen as incorporating a form of reflection, but our purpose is not to present a tool for reflective practice or for helping professionals to cope with the psychology of their complex work.i Instead, we are interested in investigating the complexities of professional practice and knowledge. We understand practice as emergent, collective and embodied, and professionals’ knowing as inseparable from the activity and materials of practice.

‘Becoming’ is a way of understanding the tensions of everyday practice and knowledge of professionals such as surgeons as far more nuanced than is often represented using conventional vocabularies of competence, error, quality and improvement. A ‘becoming’ orientation as we use it here derives not from traditions of development, which focus on individual trajectories of progressive growth. Instead it derives from the ‘practice turn’, a field of professional studies using various theories to analyse practice as emergent, collective, embodied and material, and knowing as continually being enacted and transformed in practice.4–6

In particular, we adopt Deleuze’s notion of becoming, which is about continuous change. This is not change towards a particular something that is already imagined, such as an ‘expert’ or a particular standard of practice. That is, becoming does not have an endpoint: “Becoming produces nothing other than itself… What is real is the becoming itself”.7 For Deleuze8 becoming is a creative process of making, remaking and unmaking oneself in relation to others ‘along a moving horizon, from an always decentred centre, from an always displaced periphery which repeats and differentiates’. One is not becoming a particular ‘being’, although the becoming process unfolds from a being and its environs. Becoming is always more than a being. One is always expanding into an interrelationship with others, entering their worlds in a deeply ethical sense of interdependence.9 In fact for Deleuze, becoming is about a self ‘becoming-other’.

How might we research processes of ‘becoming’ in practice? Narrative has been a popular methodology in the health professions, proving useful to get beneath clinical representations as well as offering an appealing way to share difficult experiences with colleagues and provides useful stories for educational purposes.10 However, narrative research often imposes a particular genre on lived experience. It tends to create a coherence and closure which does not reflect the dynamic immanence, fragmentation and contradictions of experience, and typically cannot address systemic dynamics in which the narrative is situated.11,12

Visual enquiry into practice is another familiar approach, particularly through methods of photo elicitation where research participants are invited to photograph and then discuss settings or objects that offer insights to their everyday practice.13 While helpful, photos too can close down the multiplicity of experience, and mediate it through the certainty and order imposed by a certain sense of visual aesthetic (what makes a good photograph).14

A slightly different visual approach, which we have adopted in this study, is inspired by Deleuze’s8,15 notions of mapping research as a way of making visible ‘the image of thought’ and new possible organisations of reality. Participants literally draw pictorial maps of their practice experiences, then talk about these pictures. This allows them to represent different forces and multisensory dimensions simultaneously, including desires, as well as the movements and interactions among them. The approach has been used in education to map students and teachers’ experiences of learning and practices of education,16 to explore practices in urban spaces17 and to map multiple literacies.18

The purpose of this article is to offer a conception of surgeons’ experiences as ‘becoming-surgeon’. We develop this conception by drawing from our Deleuze-inspired study of mapping experience, as well as upon new literature examining professional practice and knowing in terms of ‘becoming’. In addition, we argue for Deleuzian mapping as a method to research health professionals’ practice and experience, and suggest the utility of this approach as a pedagogical tool for medical education.

MAKING MAPS

Our paper deals with the use of mapping, as conceptualised by Deleuze, to conduct research for understanding clinician’s experiences with complex situations. As such, our mapping method is not intended to be therapeutic for surgeons, nor it is intended to be a tool to cope with the psychology of their work, rather it is intended to research the complexity of their work and to introduce trainees to such complexity.

Our research approach, described in fuller detail elsewhere,2,19 involved the participation of five surgeons from different specialties. Postoperatively, surgeons were invited to draw their experience of a surgery they had just conducted and how it evolved. Then, they participated in a 60 min interview to explain and reflect on their pictures. This was repeated for three different complex operations conducted by each participant, resulting in a total of 15 pictorial maps. The discussion that followed the map drawing frequently elicited new insights and understandings from participants, who were encouraged to add more details to the picture if they thought it necessary.

In our previous studies, we developed a framework to conduct a content analysis of the maps and interviews produced by participants,2,19 as follows. The pictures were aesthetically analysed to identify the individual images, and to consider them in terms of their arrangement on the page and their visual connection with other images. A cross-comparison of multiple maps produced by each surgeon was then conducted to develop an understanding of each surgeon’s visual language. During this step, we examined the stylistic principles of the maps by asking questions such as: How do they draw the story (linear, circular, scene based)? What are the patterns? Are there any motifs that occur regularly across the three pictures? How do participants use colour: symbolically, to define areas of interest, to indicate affect? How do they employ metaphors? The final step was conducted in the form of a team exercise, reflecting our epistemological stance to visual analysis where the visual is treated as a social construction, a product of the encounter between researcher and research participant.19 The participating surgeons joined us in a ‘return-of-findings’ii session designed to explore their reflections on the analytical results from the previous steps.

Visual maps can be used in research with or without an aesthetic analysis. We chose the former. As we previously demonstrated,19 highlighting the aesthetic features people use to draw their experiences offers multiple advantages. First, it opens participants’ own awareness into their visual thinking. This provoked important cues leading participants to reflect more deeply on what was emerging for them when dealing with a complex situation. Second, it helped to reveal subtle distinctions in how different participants represented similar experiences. Third, it sensitised us to meanings reflected in the geometry and dynamic movements of the lines, colour and spaces themselves comprising the pictures. This is where we began to truly see them as multifaceted maps.

Our data set abounded with visual representations of emotional affects. While analysing these, we identified a number of visual archetypes that surgeons used to describe their emotional experiences, such as ‘the outcast’, ‘the unhealable wound’ and ‘battles of light and dark’. Our iterative analytical method engaged participants in reflecting on the meaning of these archetypes. During these discussions, surgeons began to comment on the potential value of sharing their experiences with colleagues. With the participants’ consent, we arranged an arts-based display using motifs from the pictures and invited other health-care audiences to respond. Subsequently, we conducted a final ‘return-of-findings’ session with the surgeons—a follow-up meeting sharing our preliminary interpretations and the audience responses, and inviting their further reflections on their experiences of the operations and of representing these visually.

Through these processes, we began to discern particular ‘knots’, ‘twists’, ‘folds’ and ‘crossings’ in the pictures, as well as to analyse the interplay among different forces of both disruption and ordering. It is important to note that this analysis using Deleuzian concepts did not derive solely from the pictorial maps, but emerged through our various conversations with the participants.

Mapping with Deleuze

The map is open and connectable in all of its dimensions; it is detachable, reversible, susceptible to constant modification. It can be torn, reversed, adapted to any kind of mounting, reworked by an individual, group, or social formation…A map has multiple entryways, as opposed to the tracing, which always comes back to ‘the same’. The map has to do with performance, whereas the tracing always involves an alleged ‘competence’.7

The notion of a map is not of simply ‘tracing’ what already is or has been, as though a deep structure exists, but of creating an experience anew as something always in process. The forces that interact in this process are conceptualised by Deleuze and Guattari7 as different kinds of spaces and different forces of ‘lines’. What they call ‘lines of articulation’ are the ordering, normalising, homogenising forces, creating hierarchies and centres. These produce what they term ‘smooth spaces’—the ordered structures of social and material life. In contrast are ‘lines of flight’, the decentring, disruptive, dispersive forces that produce creative potentials, offshoots and sometimes escape from repression. These produce ‘striated spaces’ in Deleuzian terms—rough, unpredictable, messy fields of life.

The activity of mapping can help us to discern lines of flight and of articulation, and where and how they come together. We begin with a particular object of enquiry, such as a particular becoming that we wish to explore in our practice. We might choose particular emblematic centripetal and centrifugal forces at play in our practice, and try mapping them out. We might try representing different events, actors, objects and so on in motion, or map their effects on one another, or on producing smooth or striated spaces. We might draw problem elements that we feel need containing, or repressed elements that we think need to be ‘de-territorialised’. We might draw openings where new possibilities or ‘becomings’ that are not yet in flight might be activated. Deleuze encourages us to push beyond cause–effect thinking, or linear representations of experience and development. The opportunity is to play with the simultaneities, multiple causes, closed loops, tangles and ruptures of lived experience.

READING THE MAPS

In analysing these maps and our conversations with the surgeons who produced them, we adopted an approach suggested by de Freitas20 and looked in particular at where lines and forces intersected. We identified what appeared to us to be twists, folds, knots and crossings. The purpose was, in the spirit of Deleuze’s process ontology, to allow the practice experience to remain ephemeral and shifting, while examining its complexity and contradictions. We asked ourselves, How are key territorialising forces occurring, and how do the surgeons’ representations of these forces influence their developing practice? We also asked, where are the key disruptive forces, both those that are rogue and need containment, and those creating opportunities or ambiguities that open new possibilities for becoming?

Cycles of futility

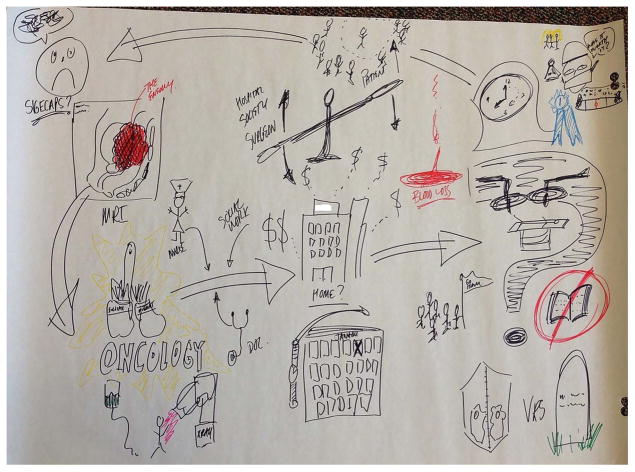

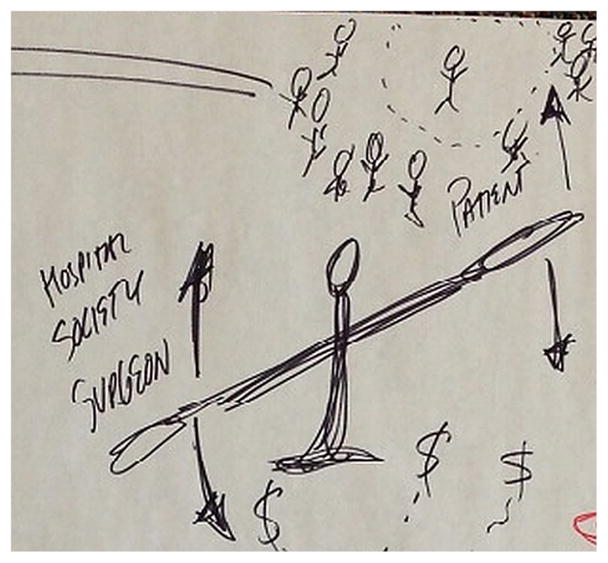

This map shows the situation as recurrent cycles of interconnected elements depicting conflict and stress. From left to right we see the ‘boxing fight’ with the oncology department to obtain approval for the surgery, funding pressures, the operating room depicted as if a giant skull and the ‘text’ of medical knowledge incapable of addressing the complexity of the operation. At the centre of this dynamic motion sits the institution, boxed and immobile compared with the flying lines crossing the map—territorialisation incarnate—underneath a scale balancing multiple actors and interests. To the left of the scale is the patient, unhappy regardless of the surgical outcome; to the right is the surgeon’s family, left disappointed (again) by promises broken by the lengthy surgery. These pictorial elements depicted lines of articulation, lines of flight and knots that together painted a convoluted story of struggles: the surgeon called it a ‘cycle of futility’ (figure 1).

But the issue around that was a back story… because he was someone who does not have a lot of intelligence, the oncologist said “well we’re not going to treat him with chemotherapy before you operate on him because we don’t think he’s reliable”… and I felt very strongly that that was inappropriate because I thought that treating him with less than the standard of care just because he’s not as smart as the next person is a bad idea. So, I felt like that was a big part of this case, which has nothing to do with the operation…

Figure 1.

Map illustrating ‘cycles of futility’.

The surgeon’s becoming—stepping into something new—is what she has volunteered while intervening in the cancer. Treating a patient with cancer with an unusual abdominal tumour who is also mentally ill constitutes one line of flight. It affords clinical as well as ethical challenges prompted by the strong call experienced by this surgeon to defend a notion of fairness. The surgeon then becomes embattled in multiple lines of institutional articulation, including all the procedural issues and decisions required of the surgeon once treatment is started. Encountering those lines of flight and lines of articulation creates a knot whose turbulent threads stretch around the map, as though it continually permeates everything else in the situation. The picture actually merges the surgeon with the continuous motion and spinoff balancing of the scale, as she asks herself, Why? (figure 2)

What that scale represents is how I’m trying to weigh whether what I think is doing the right thing may not be the right thing… and I think some people may look at it and say “Well, that was stupid because the patient doesn’t care and everyone else is fighting it. Why are you doing this?” Morality and ethical decision-making is a hard thing to draw, so that’s why I chose the scale and trying to put things on either side.

Figure 2.

Section of a map in figure 1 illustrating lines of flight and articulation.

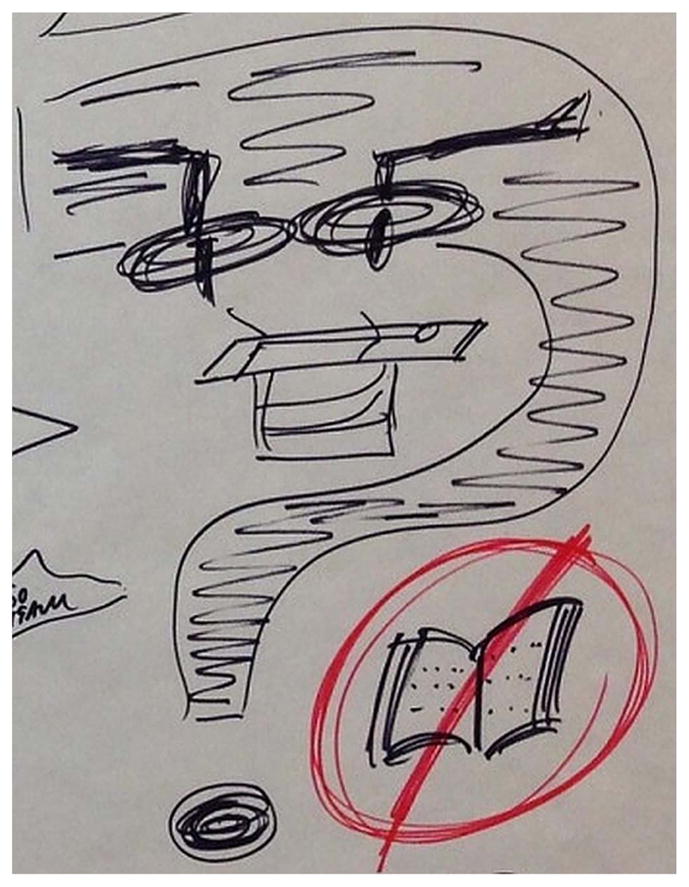

The continual ‘why’ extends to the operating table, framed in a giant question mark in a way that almost suggests a skull. Here is another knot, marking the encounter of the operating room as lines of articulation representing all the institutional equipment, procedures, protocols and giant lights exposing everything—underpinned by no-textbook, no-knowledge, forcing invention at the edge where knowledge stops (figure 3).

So, I’ve tried to represent that with the operating table, the patient lying on it, the OR lights focused on the patient, and a big question mark because we thought we could get this out but we’re not sure, and all the other questions about what to do.

Figure 3.

Section of a map in figure 1 illustrating a knot.

Traditionally, the role of physicians, distinct from other health disciplines such as nursing, has been described as ‘to treat’, not ‘to care’. In surgery, this focus on treatment has created the assumption that complex situations are directly and sometimes uniquely related to the procedural aspect of the situation. However, when other factors, such as institutional assertions of authority, gather more power and a sense of futility begins to creep up in the surgeon, questions of worth arise: “… is doing a heroic or very extensive surgery really in her best interest? Or would it be better to just not remove the tumour and make her comfortable and palliate her and let her die in comfort?” There is no resolution to these questions, as the circulating lines on the map show. Nor is the point here about developing strategies for making ‘rational’ ethical decisions, or learning ways to fight the institutional territorialisations. Rather, we see the surgeon both balancing and disrupting, as she works through the knots she is enacting along with the forces around her. Becoming-surgeon here is entering these knots voluntarily, even if one suspects yet another cycle of futility, driven by possibilities of achieving something better for a patient.

Becoming superman

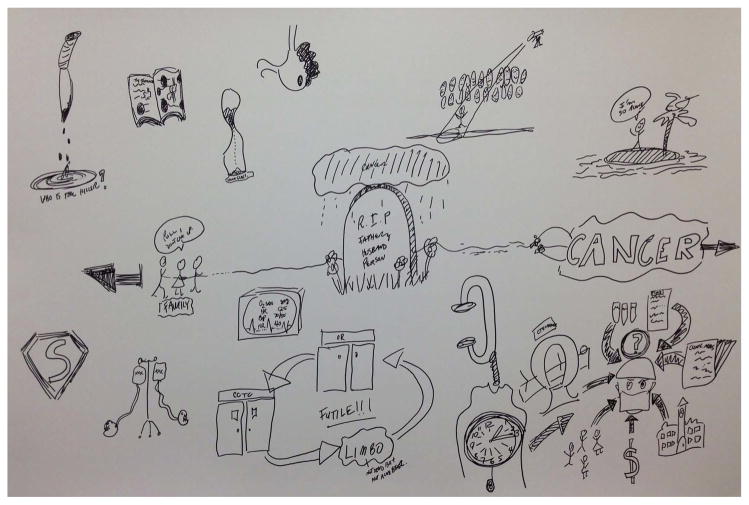

The map below recalls a key idea from Deleuze: experience in practice is a simultaneity of fragments. Here the participant represented the surgery as different moments from multiple situations, not as a sequence of events comprising one situation. No particular moment had a single line of narrative; instead it was an assemblage of different material fragments, metaphors, tangled conflicts and affective forces that moved in and out of the surgeon’s recollection on the situation at different times. Anchoring the centre of the map is a tombstone, constituting the largest line of flight both visually and metaphorically: a fight between the family’s desire and the reality of the cancer prognosis (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Map illustrating ‘becoming superman’.

The surgeon’s representations of self are all metaphoric, and all reflect isolation and vulnerability created by lines of articulation. The spotlight represents the surgeon’s anticipation of being judged during M&M (Morbidity and Mortality) Rounds. While she was acting in the present, this imagined future acted with her, affecting her decisions about what to do as if already enacting the ‘one in the spotlight’. Next to the spotlight, floating in a void, the surgeon portrays herself as alone on an island of practice, isolated from team, system and supports.

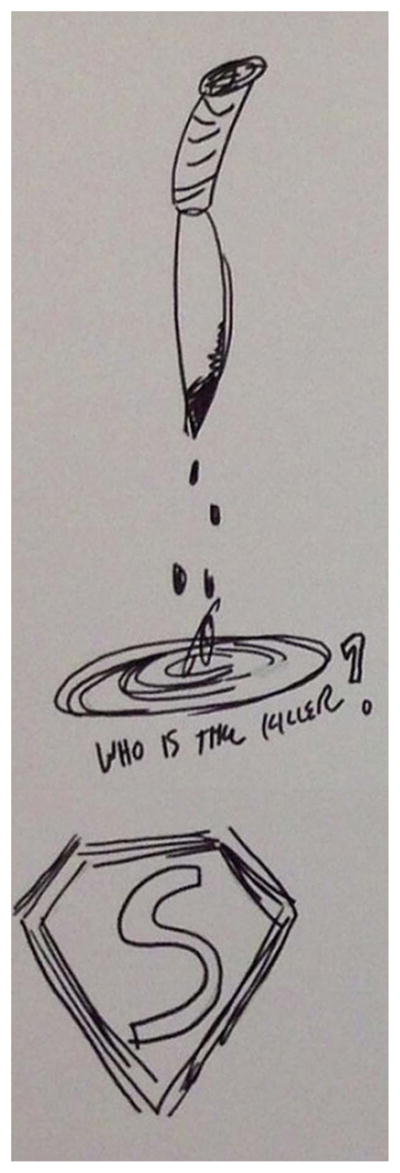

Diagonally opposite to this island the surgeon has drawn a superman symbol. Disembodied, decontextualised, stripped of all human content, this symbol was instantly recognised by the other surgeons. They acknowledged it as a fair representation of the perception of the people outside the OR who expect surgeons to produce heroic, even impossible, solutions. This expectation of becoming superman/superwoman seems to be about putting on the symbol but also hiding it. The symbol represents an interesting knot of being caught between demands for confident, capable performance in spite of sometimes lacking the required knowledge (holes in a textbook), being controlled by external threat (the dripping knife) and being subjects of systemic cycles of futility (depicted to the right of superman symbol). Surgeons appear to be required to be superman, even when they are trapped in a knot. Do surgeons see that assumption critically? They seem to be critical when asked by saying that ‘people think they are superman but they think they are not, that they don’t see themselves as such’.iii However, when in the midst of the situation and particularly in critical moments, surgeons admit that they find themselves stepping into that superman role that takes control and saves the day: controlling emotions, solving personality disputes, fixing errors.

Here we ponder, if becoming surgeon is partly being willing to wear the superman symbol, how do surgeons deal with the ultimate responsibility that comes from wearing that symbol? (figure 5)

The superman symbol was just the expectation of the family, I think, that we would save this guy when it was thought to be a non-savable situation.

The next thing beside it is very morbid but I was trying to think of something that represented killing someone and so it’s a knife with blood dripping off it and the question is who is the killer? When you operate on these people, you don’t want to be the person that’s pushed them over the edge and kill them. They’re dying of a natural process, their cancer. That’s no one’s fault. No one caused that to them, no one did anything bad to them. It’s back luck they just caught it and that’s the way the world works. But when you intervene and do something to someone and operate on them and cause them to die because of your intervention, or that process which is occurring him dying has sped up, then sometimes you often think inside yourself that you actually killed someone despite the fact you’re trying to help them.

Figure 5.

Section of a map in figure 2 illustrating a knot.

Other lines of articulation, lines of flight, knots, folds and striated spaces complicate this notion of becoming superman. The cycle demarked by the Operating Room (OR) and the Critical Care Trauma Centre (CCTC) and labelled as ‘futile’ is an example of a fold because it shows how a line of articulation (ie, the normal pathway that certain patients go through between the OR and the CCTC) creates in itself a line of flight in the form of futility and limbo. Next to those representations of futility, the surgeon draws herself surrounded by multiple stressors or lines of flight, which together create what Deleuze refers to as a striated space. Paradoxically, every one of those lines of flight arises from a line of articulation, such as structured tests, money, operating room time, that might be slightly at the edge of chaos. General representations of time (eg, clock, hourglass) constitute lines of articulation, prompting the situation to move forward in an orderly way. However, the chaotic nature of this particular situation, as a line of flight, prevents it from fitting within the clock. The clock and the high demands of the situation twist together to increase the stress, here represented by the dripping knife in close proximity to the clock and the superman symbol. In fact, this was a common twist that we observed across all the maps we collected from surgeons.

Taken together, these maps suggest that the notion of becoming surgeon ‘changes from day to day or from month to month’. Surgeons tend to believe that ‘the whole superman idea is right’. Nonetheless, complex situations seem to make them ‘wonder if at times we overestimate how much we think patients and their families expect a superman and how much of it is more of an internal expectation.’

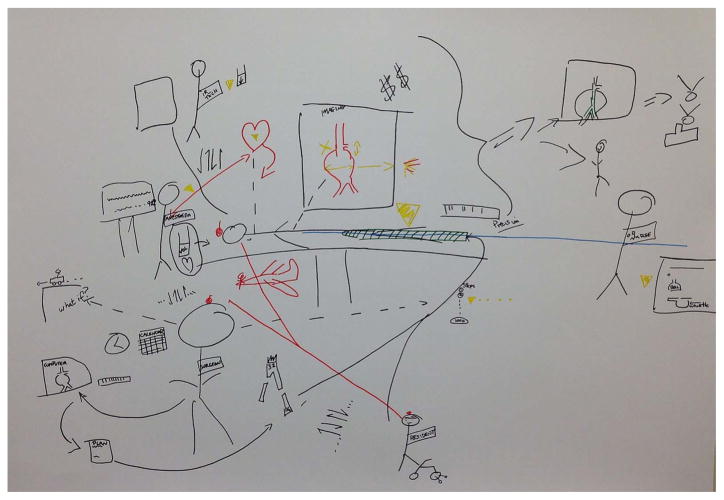

Coming to trust

A third motif we suggest as directly related to our discussion of becoming-surgeon is a dynamic of coming to trust. Trust, as in the map below, emerges from the encounter of lines of articulation and lines of flight during moments of uncertainty (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Map illustrating ‘coming to trust’.

The use of colours seems to be a visual strategy shared by surgeons to depict these encounters. For instance, the dollar sign constitutes a line of articulation that is usually present in surgical procedures: ‘does the benefit of the operation justify the cost?’ Yellow and red objects are prominent disruptions to the status quo of the operating room and constitute lines of flight. While they do not seem to be in stark contrast with the lines of articulation in the map (eg, procedures, technology, tools), they meet and coexist in the operation without affecting each other.

In ‘coming to trust’, the uncertainty and stress that comes with allowing the resident to operate constitutes a line of flight —represented in red. Simultaneously, a line of articulation is generated from the system of surgical training following an apprenticeship model, where learning-by-doing is the key premise. The surgeon must work with the resident, must train the resident and ultimately is compelled to rely on the resident.

But then as I was going through, I was thinking but how do you depict the trust [in the form of a William Tell analogy: apples on the heads of the surgeon, the patient and the resident joined by red arrows] when you say to the resident, okay, you’re going to do this step. The resident is never going to say or rarely going say “No, I can’t do it”. But you know a patient comes knowing it’s a teaching centre, knowing that there are residents involved with the care but they don’t really know to what extent. And when it’s an operation, they know it’s a team doing it. I think probably a lot of them would think that the surgeon is doing the whole thing and the residents are sitting and watching them.

This realisation highlights that part of becoming surgeon is becoming mentor and a facilitator of others’ learning. However as surgery is a high-stakes profession, the ‘doing’ is inextricably linked to who owns responsibility: the surgeon. When residents are involved in a surgical operation as part of their training, they are allowed to ‘do’ parts of the procedure at discretion of the surgeon. How do surgeons develop the trust for this permission, and decide what residents may ‘do’? As our maps revealed, there is no clear handover but a delicate series of negotiations: a letting go and reining in, sometimes a leap of faith based on interpersonal trust. The encounter of lines of flight and lines of articulation that work alongside each other without affecting each other, usually guides this decision—something that patients sometimes are not aware of.

Working alongside an apprentice resident raises another dimension of becoming-surgeon: managing the contradictions of performing this role of ‘superman’, making magic happen and bearing the full burden of responsibility, while at the same time allowing this other to also become-surgeon in their own maps of complex experience. How does superman relinquish control, and even change in this process? How does another superman unfold from the nesting trust of sheltered apprentice embedded in another’s practice? These may be useful questions for both experienced and student professionals to reflect upon in their various processes of becoming-surgeon.

CONCLUSION: SHAKING OUT THE MAPS

This discussion addresses the current interest around understanding professionals’ learning in practice, with a focus on surgeons. Its point of departure is to understand practice as ‘becoming’, drawing from Deleuze’s8 concept of becoming as a process of continually encountering differences in our relationships with the people and materials around us. This is not a trajectory to a particular predetermined endpoint, as though professional learning is about becoming an already decided identity or master of already known skills. Instead, Deleuze prompts us to understand becoming as attending and opening to the different not-yet-realised possibilities that are always being presented to the practitioner in the turmoil of the field of practice. In that field we are of course constantly repeating routines, strategies and problems—but in each of these iterations, difference beckons. We are never a stable being, but always becoming-other than what we were, in a process suspended between what we were and knew and did a moment ago, and the different self that awaits us a moment hence.

In applying this understanding to surgeons’ visual maps of their practice experience, we believe that it offers a more nuanced way to appreciate the conflicting forces, the undecidability and the different futures confronting them. Their process of becoming-surgeon does indeed seem more accurately portrayed as moving within these forces, and continually changing, rather than as acquiring skills and following protocols. Their process also clearly echoes Deleuze’s emphasis on becoming as an embodied relation with many human and non-human things, rather than just being about an individualised cognitive process of decision making. In this short article, we selected only three motifs appearing in the surgeon’s drawings and interviews to help illustrate some of these movements: cycles of futility, becoming-superman and coming to trust. These are not offered in the spirit of flattening surgeon’s multifaceted experience into three themes. Instead, these are intended as sites for exploring the lines of flight and lines of articulation that constitute surgeons’ fields of practice, and the knots, twists, folds and crossings of these lines that help prompt their unique process of becoming-surgeon.

We also suggest that this activity of drawing maps of experience and talking about them offers a useful method for researching health professionals’ practice and experience, not to replace but to complement other approaches. The main advantages of these maps and a Deleuzian reading of them are in interrupting the closure and the sense of fixity and uniformity that can result from other qualitative methods examining professionals’ learning. The maps also invite into the research a simultaneous multitude of issues that are not so easily captured in linear interviews, narratives and surveys.

Finally, we suggest that these maps offer a potentially useful pedagogical tool for medical education for students sufficiently advanced to reflect on internship experiences. Clearly the drawing activity is only the starting point; the dialogue with students about what the pictures mean is critical. Key to this dialogue will be engaging students in thinking about becoming, how to recognise lines of articulation and lines of flight in their maps, how to appreciate the movements and contradictions there and perhaps even to analyse how they negotiated the knots, twists, folds and crossings. It is in these sorts of conversations that important discussions can open about the alternate spaces opening up, and the generative possibilities that beckon in their own processes of becoming-professional.

Footnotes

One reviewer of an earlier draft of this article suggested that the approaches discussed here might be useful as a therapeutic tool, drawing attention to Guattari’s work with psychiatric patients. While this was not the purpose of our study or this paper, the idea may be worth investigation in other research.

Return-of-finding refers to follow-up meetings with the participants in which preliminary findings are discussed in order to achieve consensus in the interpretation and analysis of the data.

All quoted statements within paragraphs and next to the pictures are participants’ comments. To protect anonymity, we are not including any identification information.

Contributors Both authors conceptualised, conducted data analysis, prepared and revised the manuscript.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Scanlon L, editor. ‘Becoming’ a professional: an interdisciplinary analysis of professional learning. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cristancho SM, Bidinosti SJ, Lingard LA, et al. What’s behind the scenes? Exploring the unspoken dimensions of complex and challenging surgical situations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1540–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—the pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolini D. Practice theory, work, and organization: an introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenwick T, Nerland M, Jensen K. Sociomaterial approaches to conceptualising professional learning and practice. J Educ Work. 2012;25:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hager P, Lee A, Reich A. Practice, learning and change: practice-theory perspectives on professional learning. Dordrecht; Heidelberg; New York; London: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deleuze G, Guattari F. A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deleuze G. Difference and repetition. New York: Columbia University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semetsky I. Becoming-other: developing the ethics of integration. Pol Futures Educ. 2011;9:138–44. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandler A. Narrating the self-injured body. Med Humanit. 2014:40111–16. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2013-010488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyvärinen M, Hydén L-C, Saarenheimo M, et al. Beyond narrative coherence. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson CL. Re-presenting the subject: problems in personal narrative inquiry. Int J Qual Stud Educ. 1997;10:455–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper D. Talking about pictures: a case for photo elicitation. Vis Stud. 2002;17:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pink S. Doing visual ethnography. London; Thousand Oaks; New Delhi: SAGE; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deleuze G, Bacon F. Francis bacon: the logic of sensation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin AD, Kamberelis G. Mapping not tracing: qualitative educational research with political teeth. Int J Qual Stud Educ. 2013;26:668–79. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coleman R, Ringrose J. Deleuze and research methodologies. Edinbugh: Edinburgh University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masny D, Cole DR. Mapping multiple literacies: an introduction to deleuzian literacy studies. London; New York: Continuum Internation Pub. Group; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cristancho S, Bidinosti S, Lingard L, et al. Seeing in different ways: introducing “rich pictures” in the study of expert judgment. Qual Health Res. 2014;25:713–25. doi: 10.1177/1049732314553594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Freitas E. The classroom as rhizome: new strategies for diagramming knotted interactions. Qual Inq. 2012;18:557–70. [Google Scholar]