Abstract

Apoptosis is important in regulating cell death turnover and is mediated by the intrinsic and death receptor-based extrinsic pathways which converge at the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) leading to mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP). MOMP results in the release of apoptotic proteins that further activate the downstream pathway of apoptosis. Thus, tight regulation of MOMP is crucial in controlling apoptosis, and a lack of control may lead to tissue and organ malformation and the development of cancers. Despite a growing number of studies focusing on the structure and activity of the proteins involved in mediating MOMP, such as the Bcl-2 family proteins, the mechanism of MOMP is not well understood. In particular, the crucial role of the various structural properties and changes in lipid components of the MOM in mediating the recruitment and activation of different Bcl-2 proteins remains poorly understood. Furthermore, the factors that control the changes in mitochondrial membrane integrity from the initiation to the final disruption of MOM have yet to be clearly defined. In this review, we provide an overview of studies that focus on the mitochondrial membrane with a biophysical analysis of the interactions of the Bcl-2 proteins with the mitochondrial membrane.

Keywords: Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), Bcl-2 proteins, Mitochondria, Membrane interactions, Apoptosis

Introduction: initiation of MOMP

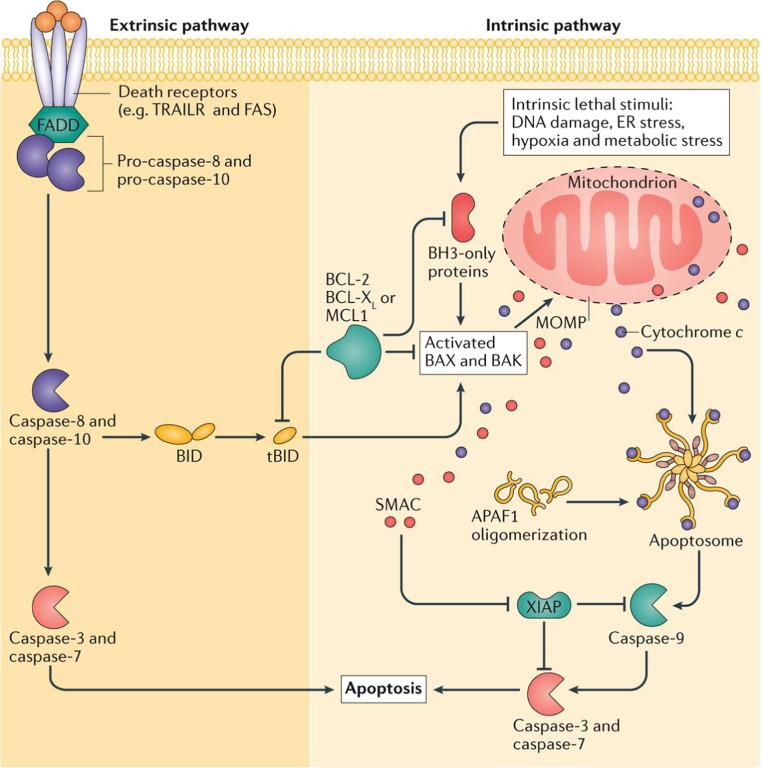

Apoptosis regulates cell turnover in healthy living organisms by eliminating unhealthy as well as excess cells and also plays a role in tissue development and ageing. The apoptotic process is comprised of two main pathways, the death receptor pathway (extrinsic) and the mitochondrial mediated pathway (intrinsic) (Czabotar et al. 2014; Elmore 2007; Ichim and Tait 2016; Tait and Green 2010) and are summarized schematically in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of intrinsic and extrinsic pathways of apoptosis. In the extrinsic apoptotic pathway, upon binding to their cognate ligand, death receptors such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptor (TRAILR) and FAS can activate initiator caspases-8 and 10 through dimerization mediated by adaptor proteins such as FAS-associated death domain protein (FADD). Active caspase-8 and caspase-10 then cleave and activate the effector caspase-3 and caspase-7, leading to apoptosis. The intrinsic pathway of apoptosis requires mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP). Cell stresses trigger Bcl-2 homology domain 3 (BH3)-only protein activation, leading to BAX and BAK activity that triggers MOMP. Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins counteract this. Following MOMP, mitochondrial intermembrane space proteins such as second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases (SMAC) and cytochrome c are released into the cytosol. Cytochrome c interacts with apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (APAF1), triggering apoptosome assembly, which activates caspase-9. Active caspase-9, in turn, activates caspase-3 and caspase-7, leading to apoptosis. Mitochondrial release of SMAC facilitates apoptosis by blocking the caspase inhibitor X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP). Caspase-8 cleavage of the BH3-only protein BH3-interacting death domain agonist (BID) enables crosstalk between the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways. ER endoplasmic reticulum; MCL1 myeloid cell leukaemia 1; tBID truncated BID. Reproduced with permission from Tait and Green (2010)

The activation of the extrinsic pathway is initiated by transmembrane receptor-mediated interactions. These death receptors are a subset of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family (Brown and Attardi 2005), consisting of a cytoplasmic domain of about 80 amino acids known as the “death domain”. The death domain plays a critical role in transmitting the death signals from the cell surface to the intracellular signaling pathways via binding of ligands (. .FasL/FasR) to their corresponding death receptors (e.g. TNF-α/TNFR1). these receptor-ligand interactions result in receptor clustering and the recruitment and oligermerisation of adaptor proteins such as FADD to the Fas receptor. Following recruitment and oligomerization of FADD, procaspase-8 binds to the FADD through dimerization of their death effector domain resulting in the formation of the death-inducing signalling complex (DISC), and the autocatalytic activation of caspase-8. The activation of caspase 8 ultimately triggers the execution phase of apoptosis (Fig. 1).

The intrinsic apoptotic pathway (Fig. 1) is often deregulated in cancer and can be initiated by a range of physical, chemical and pathophysiological stimuli including lysosomal/ER stress, DNA damage, metabolic stress, cellular stress caused by ionizing radiation, heat, hypoxia, cytokine deprivation and chemotherapeutic drugs. These diverse stimuli indicate a complex interplay of Bcl-2 proteins that triggers the executuon phase of apoptosis which is manifested by the formation of the apoptotic pore, loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and release of cytochrome c, Smac/DIABLO from the intermembrane space into the cytosol. These pathways converge at an execution pathway involving activation of caspase 3/7 by caspase 8/9 for the initiation of the cell death. As a result, the cell forms into small apoptotic bodies which are then engulfed by phagocytosis (Elmore 2007; Fulda and Debatin 2006; Ichim and Tait 2016). These pathways are not completely independent of each other, and often activation via one pathway will induce the other (Chen et al. 2015; Kaufmann and Hengartner 2001; Wong 2011).

Cytochrome c, once released from the mitochondrial intermembrane space into the cytosol, forms a large complex with Apaf-1 and pro-caspase-9, called the apoptosome (Li and Yuan 2008). Activation of caspase-9 within the apoptosome further activates the effector pro-caspase 3 and 7 via cleavage of their pro-domains. The pro-apoptotic factors such as Smac/Diablo act to prevent inhibition of the caspase cascade and further drive apoptosis (Adams 2004; Breckenridge and Xue 2004; Qin et al. 2012) (see Fig. 1). The final permeabilization step and the initiation of MOMP is regulated by disruption of the balance between the pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members. Additionally, the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways cross-link through caspase-8 cleavage of the BH-3-only protein, BH3-interacting domain death agonist (Bid), which generates active truncated Bid (tBid). The activated BH-3-only protein then interacts with and activates the pro-apoptotic effector proteins inducing the MOMP (Kantari and Walczak 2011).

Bcl-2 protein-mediated mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP)

MOMP is the key event associated with the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis (Czabotar et al. 2014; Westphal et al. 2014). The integrity and permeabilization of the MOM is highly regulated and controlled by the interactions between different Bcl-2 family proteins and the MOM. Therefore, this review aims to summarize the impact of changes in membrane composition and structure upon various stress stimuli on the interactions of various classes of Bcl-2 proteins in the cytosol and at the MOM leading toward MOMP.

While Bcl-2 proteins are found both in the cytosol or bound to the MOM, in the presence of apoptotic stimuli they are recruited to the MOM and induce membrane permeabilization. To delineate the mechanism by which the Bcl-2 family proteins induce MOMP, studies have focused on the morphological changes in the mitochondrial membrane induced by the Bcl-2 family using fluorescence imaging, SEM and AFM on native mitochondria and model mitochondrial membranes (discussed below). A number of models have been described which include modulation of the pre-existing mitochondrial channel by the Bcl-2 proteins, namely the mitochondrial permeability transition pore complex (mPTP) which consists of VDAC, ANT and cyclophilin D (Karch and Molkentin 2014). Earlier studies showed that deletion of mPTP components has no effect on MOMP and apoptosis (Baines et al. 2007), thus indicating that the interaction with mPTP is not necessary for membrane permeabilization. Moreover, formation of the mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel (MAC) mediated by Bax/Bak has also being ruled out, since MOMP results in both small and large molecule release whereas MAC only allows limited molecule sizes to pass through (Tait and Green 2010). Bcl-2 proteins are also able to interact with ceramide channel-forming sphingolipid to induce permeabilization (Chipuk et al. 2012) or by forming putative cytochrome c release channels on the MOM which is functionally redundant to Bax/Bak (Dejean et al. 2005). However, it now appears that Bax/Bak oligomerization is the key step in the formation of the apoptotic pore in the membrane for the permeabilization (Garcia-Saez 2012). The formation of this apoptotic pore is also evident from the liposome permeabilization of the model mitochondrial outer membrane induced by Bcl-2 family proteins (Baines et al. 2007; Bleicken et al. 2016; Cosentino and Garcia-Saez 2014, 2017; García-Sáez et al. 2011; Kushnareva et al. 2012; Ros and García-Sáez 2015; Shamas-Din et al. 2015; Tait and Green 2010).

The role of proteins in MOMP: the Bcl-2 protein family

The structures of Bcl-2 family proteins contain several conserved regions known as Bcl-2 homology domain (BH domain) (Fig. 2) and are classified into multi-domains (BH1–4) and single domain (BH3-only proteins) according to these conserved domains.

Fig. 2.

BH domains found in each of member of the Bcl-2 family proteins (Martinou and Youle 2011)

The multi-domain Bcl-2-related proteins are further classified into two subfamilies according to protein function; pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic/pro-survival proteins. Meanwhile, single domain BH3-only proteins have also been functionally classified into direct activators and de-repressor/sensitizer proteins (as listed in Table 1).

Table 1.

List of Bcl-2 protein family members according to their sub-classes

| Multi-BH-domains proteins | BH3-only proteins (pro-apoptotic) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-apoptotic proteins | Anti-apoptotic proteins | Direct activators | De-repressors/sensitizers |

| Bax | Bcl-xl | Bid | Bad |

| Bak | Bcl-2 | Bim | Bik |

| Bok | NOXA | PUMA | BMF |

| Bcl-w | HRK | ||

| Mcl-1 | NOXA | ||

| A1/BFL1 | |||

| Bcl-B | |||

Pro-apoptotic proteins are often termed effector proteins as they directly interact with the MOM to promote membrane permeabilisation upon their activation by BH3-only activator proteins. BH3-only proteins function as pro-apoptotic has also been characterized. In contrast, anti-apoptotic proteins prevent MOMP by binding to and inhibiting the membrane interaction of pro-apoptotic proteins and BH3 activators proteins. BH3-only proteins can function either as inhibitors of anti-apoptotic proteins (sensitizers) (Certo et al. 2006; Chipuk et al. 2008) or as activators of pro-apoptotic proteins to promote MOMP (Eskes et al. 2000; Letai et al. 2002).

Structural basis of Bcl-2 family protein activation

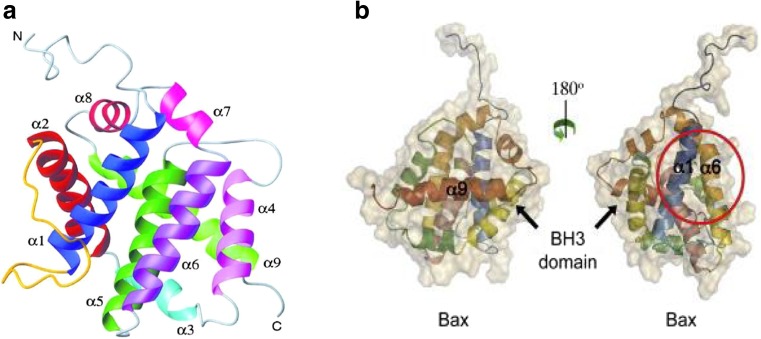

Bcl-2 family proteins exist as two conformational states: soluble cytosol-inactive monomer and the membrane-bound monomer. Pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins share a similar protein structure composed of nine α-helices. Hydrophobic helices are positioned in the center of the globular structure and surrounded by two amphipathic helices as shown in Fig. 3a using Bax as an example. This domain comprises BH1 (α4–α5) and BH2 (α7–α8) regions on one side, and the BH3 region (α2) and α3 helices on the other side. This hydrophobic region serves as the binding groove of the BH3 domain of Bcl-2 proteins and is required for protein activity especially for dimerization and oligomerization (Suzuki et al. 2000). This hydrophobic groove also serves as the binding site for the C-terminal α9 helix of Bax in the inactive conformation and is referred to as the BH3 and C-terminus binding groove or the BC groove (Chipuk et al. 2010) (Fig. 3b, left-side). In addition to the BC groove, a novel binding site was discovered in Bax (but not yet identified in Bak) which is opposite the BC groove and called the ‘rear’ groove which involves α1 and α6 helices (Fig. 3b, right-side) (Gavathiotis et al. 2008), and interacts with tBid BH3-only protein to activate Bax. The α9 helix is displaced and inserted into the mitochondrial membrane followed by the Bax activation process. Another unique structural feature of inactive Bax is the presence of a 6A7 N-terminal epitope exposed upon transient interaction with the membrane (Yethon et al. 2003).

Fig. 3.

a Overall structure of Bax showing the position of the helices. Ribbon representation is based on NMR results showing α5 is in the center of the protein structure. Reproduced with permssion from Suzuki et al. (2000). b Left-side α9 helix binds to the hydrophobic groove. Right-side When rotated 180o, ‘rear’ groove is found in the red ring which includes α1 and α6 helices. Reproduced with permssion from Martinou and Youle (2011)

Unlike other Bcl-2 proteins which are localized in the cytosol in their inactive state, the pro-apoptotic protein Bak is constitutively bound to the membrane protein-voltage-dependent anion ion channel (VDAC2) on the MOM in its inactive conformation (Cheng et al. 2003; Leber et al. 2007). Following the cleavage of Bid to tBid by the activated caspase 8, tBid binds to Bak, displacing VDAC2 to expose its BH3 domain for Bak activation (Cheng et al. 2003).

Similarly to pro-apoptotic proteins, the anti-apoptotic Bcl-xl has its transmembrane domain helix bound to the hydrophobic BC groove (Muchmore et al. 1996). Membrane-bound Bcl-xl can inhibit tBid and cytosolic Bax from being recruited onto the membrane, and thus prevents Bax activation and oligomerization, respectively (Billen et al. 2008). This inhibition occurs via the groove:BH3 interface and in the presence of the membrane. Essentially, anti-apoptotic Bcl-xl can inhibit both upstream and downstream of Bax activation (Sattler et al. 1997).

In the presence of an apoptotic signal, activator BH3-only proteins undergo post-translational modifications including proteolytic cleavage and phosphorylation for their activation (Shamas-Din et al. 2011). For instance, activator Bid protein undergoes cleavage at its unstructured loop by caspase-8 in the presence of apoptotic stimuli to result in the helical rearrangement near the cleavage site, and thus exposing the partially conserved hydrophobic residues on the BH3 domain (Chou et al. 1999). The changes in the surface charge contribute to the membrane localization via electrostatic interaction between the protein and the membrane (Shivakumar et al. 2014). Cleaved Bid (cBid) consists of two fragments, p7 and p15 (tBid), held together by hydrophobic interaction (Gross et al. 1999). cBid also interacts with a mitochondrial membrane protein, mitochondrial carrier homologue 2 (Mtch2) on the MOM (Zaltsman et al. 2010) which mediates its membrane recruitment. Upon membrane insertion, the N-terminal fragment is dissociated from the structure to expose the hydrophobic helices (Chou et al. 1999) which further promote structural rearrangements that expose the BH3 domain for interaction with Bcl-2 proteins (Oh et al. 2005). The active form Bid (tBid) then interacts with inactive Bax via its 6A7 N-terminal epitope resulting in the conformational changes releasing the α9 C-terminus to anchor Bax to the membrane (Leber et al. 2007). These specific changes in Bcl-2 protein structure are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the structural forms of the proteins and the main steps that occur during the conformational changes of Bcl-2 proteins from their inactive form to the active state

| Inactive Bcl-2 proteins |

Conformational changes |

Active Bcl-2 proteins | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activator BH3-only proteins | Inactive Bid | Active Bid | |

| • Hydrophobic helices, α6 & α7, are surrounded by amphipathic helices | • Cleavage by capase-8 gave cBid which comprise p7 and p15 (tBid) fragments • Exposure of more hydrophobic residues aid membrane insertion |

• Membrane insertion mediated by α6- α8 helices • Dissociation of p7 N-terminal fragment • Exposure of BH3 domain for interaction with other Bcl-2 proteins |

|

| Pro-apoptotic protiens | Inactive Bax | Active Bax | |

| • α9 C-terminal helix occupies the BC groove • Exposure of 6A7 N-terminal epitope upon transient interaction with the membrane |

• BH3 domain of tBid binds to Bax’s ‘rear’ groove • Displacement of α9 helix from BC groove • α9 helix then inserted into the membrane and anchor Bax to the membrane |

• Vacant BC groove for binding of BH3 domain from Bax monomer for oligomerization | |

| Anti-apoptotic proteins | Inactive Bcl-xl | Active Bcl-xl | |

| • Hydrophobic BC groove is occupied with the transmembrane (TM) domain | • Interaction with BH3 ligand from tBid displaces TM from BC groove • Membrane binding via TM domain |

• Heterodimerization with Bax via two interfaces; i) Bcl-xl BC groove: BH3 Bax ii) α1 Bcl-xl: α1 Bax |

The role of mitochondrial membrane lipids in MOMP

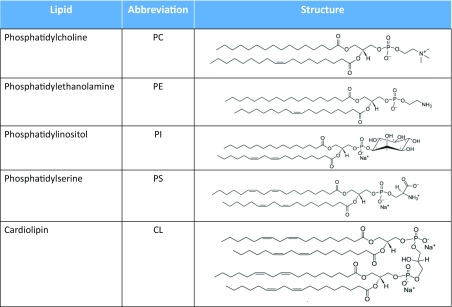

The mitochondrial membrane primarily comprises phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) (typically 70–80%), with 1–5% phosphatidylinositol (PI), sphingomyelin (SM) and phosphatidylserine (PS). The cardiolipin (CL) content differs in mitochondrial inner and outer membranes with 20% and 5–10%, respectively (Horvath and Daum 2013). Tables 3 and 4 show the structure of mitochondrial phospholipids commonly identified from different tissues and organisms (Cosentino and García-Sáez 2014; Horvath and Daum 2013). These values are used to formulate the lipid composition in constructing model membranes mimicking the composition of specific membranes, particularly the MOM. Specific lipid components in the mitochondrial membrane have a critical role in the interaction between Bcl-2 family members and mediating the conformational changes during protein–protein interactions at the membrane surface. Indeed, the presence of cardiolipin in mitochondria plays a functional role in protein interactions (Cosentino and García-Sáez 2014; Schlame et al. 2000).

Table 3.

Chemical structures of phosphoglycerolipids found in mitochondrial membranes

Table 4.

The phospholipid composition of the mitochondria acquired from human heart tissue, C3HA rat liver cells, hepatoma cells and Saccharomyces cervisiae

| Source | POPC | POPE | POPI | POPS | POPA | CL | Others | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human heart | 36 | 28 | 6 | 5 | 17 | – | 8 | Gloster and Harris (1970) |

| Rat liver (OMM) | 45.4 | 30.4 | 8.4 | – | 9.5 | – | 6.2 | Garcea et al. (1980) |

| Rat liver (C3HA) | 54.7 | 33.4 | 6.8 | 2.1 | 18.3 | – | 0.0 | Colbeau et al. (1971) |

| Hepatoma – 22 | 37.4 | 26.7 | 11.0 | 6.4 | 10.2 | – | 8.3 | Bergelson et al. (1970) |

| Saccharomyces cervisiae (OMM) | 58 | 17 | 19 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Bürgermeister et al. (2004) |

The yeast mitochondrial fraction is specific to the outer mitochondrial membrane while fractionation of the rat liver, hepatoma and human heart cell involved compositional analysis of the entire mitochondria. Membrane composition is in percentage (%)

While the compositions listed in Table 4 are obtained from healthy cells or tissues, changes in the membrane lipid compositions during apoptosis have also been well documented (Crimi and Degli Esposti 2011; Jourdain and Martinou 2009). In particular, the changes following stimulation of the extrinsic or intrinsic pathways have been compiled in various cell systems and reviewed in detail (Crimi and Degli Esposti 2011). Table 5 lists some of the changes in lipid composition in the mitochondria before or after the onset of MOMP following induction of the intrinsic pathway (Crimi and Degli Esposti 2011). Overall, it has been observed that the earlier lipid changes relate to an initial deficiency in PC biosynthesis which may impact on CL production. Very few of the lipid changes occur before the onset of MOMP which may be involved in priming the membrane for the apoptotic action of Bcl-2 proteins. For example, it is possible that changes in different lipids during the apoptotic process influence the membrane recruitment of Bax and Bak which ultimately affects the formation of the apoptotic pore. It has also been suggested that Bid may play a role in the transfer of these lipids from the ER membrane to the mitochondrial outer membrane (Degli Esposti et al. 2003).

Table 5.

Lipid changes in the mitochondrial membrane during apoptosis following mitochondrial pathway stimulation

| Lipid species | Cell system | Death stimulus | Change | Timing of MOMP | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleyl-PC+ | Jurkat T | Erucyl-PC | Decreases | Before | Crimi and Degli Esposti (2011) |

| Peroxidized CL | Various cells | Pro-oxidants | Increase | Before and after | Tyurin et al. (2008) |

| Cardiolipins | Cardiomyocytes | Palmitate | Decrease | Not tested | Matsko et al. (2001) |

| Granulose | Stearate | Decrease | Not tested | Matsko et al. (2001) | |

| Neurons | PC starvation | Decrease | Not tested | Kirkland et al. (2002) | |

| Phosporylated PI | Jurkat T | Erucyl-PC | Increase | Before and after | Crimi and Degli Esposti (2011) |

| Truncated ox PC | Mouse liver | Truncated ox PC | Increase | Before and after | Chen et al. (2009) |

. The timing ‘before’ and ‘after’ refers to the time at which changes are observed relative to MOMP. Adapted with permission from (Crimi and Degli Esposti 2011)

Taken together, it is clear that the individual lipids play a central role in defining the interactive properties of the mitochondrial membrane, and provide the basis for the design of model membranes based on these defined lipid compositions, to provide more insight into the role of mitochondrial lipid in the membrane interaction of the Bcl-2 protein family and subsequent MOMP.

Membrane targeting of activator Bcl-2 proteins is among the early steps for the recruitment of effector Bcl-2 family members to the MOM for permeabilization. The lipids that have been shown to affect membrane recruitment of Bcl-2 proteins are cardiolipin (CL), cholesterol (Lucken-Ardjomande et al. 2008a) and sphingolipid. (Lutter et al. 2000; Shamas-Din et al. 2015). CL is a negatively charged phospholipid which normally resides in the mitochondrial inner membrane (MIM) (Schlame et al. 2000) with only small amounts (3%) present in the MOM (Hovius et al. 1990). Translocation of CL from MIM to MOM has been reported and occurs via the contact sites between the two membranes (Ardail et al. 1990).

The increase in membrane surface negative charge as a result of increased CL content in the OMM has been shown to enhance the electrostatic interaction of the direct activators Bid and Bim with the membrane. Depletion of anionic lipids phosphatidylinositol and phosphatidylserine, and CL in the neutral phosphatidylcholine membrane, resulted in low cBid and Bim binding to the membrane (Shamas-Din et al. 2015). In addition to acting as a docking site for the Bcl-2 proteins, CL also interacts with cytochrome c at the outer leaflet of the inner mitochondrial membrane (Rytömaa et al. 1992). Together with the presence of reactive oxygen species during the early apoptotic event, CL undergoes peroxidation in which it releases the bound cytochrome c from the mitochondria (Kagan et al. 2005) for the downstream event of apoptosis.

Liposomes composed of mitochondrial lipids were used to analyze the ability of pore formation induced by full-length Bax A (Satsoura et al. 2012). The study showed that the presence of tBid is important for the insertion and pore formation by Bax. It was demonstrated that tBid-activated Bax binds to the membrane and rearranges itself so that it protrudes from the membrane layer (analyzed by small-angle neutron scattering). However, the membrane conformation of Bax is still unknown (Satsoura et al. 2012).

Using immunoelectron tomography, it has also been shown that tBid localizes to the contact site containing cardiolipin (Lutter et al. 2000). In the absence of CL, tBid conformational change is compromised but not the binding to the membrane. This suggests that tBid-membrane recruitment depends on the interaction between the negatively charged CL and the positively charged residues of the membrane-binding helices of tBid (Shamas-Din et al. 2015). However, how cardiolipin affects tBid conformation and mediates Bax insertion remains unclear. CL also affects the activation of Bim and mediates Bax insertion and oligomerization in a liposome (Lucken-Ardjomande et al. 2008b). Likewise, CL is required for Bax recruitment and mediated the Bax conformational change for its activation (Dingeldein et al. 2017; Lucken-Ardjomande et al. 2008b).

The presence of cholesterol reduces the cBid and Bim membrane binding. However, while cholesterol content of up to 20% in liposomes impaired the tBid conformational change, this was not the case in the membrane with 8% cholesterol (Shamas-Din et al. 2015). Bax activation and membrane insertion for permeabilization significantly reduced with high cholesterol content (Christenson et al. 2008; Lucken-Ardjomande et al. 2008a; Shamas-Din et al. 2015). Increased cholesterol content up to 20% in liposomes resulted in a significant reduction of membrane fluidity which may hamper the proteins’ membrane insertion and activation (Lucken-Ardjomande et al. 2008a). High levels of cholesterol in many tumor cells may be one of the mechanisms to prevent apoptosis and promote their survival and may also contribute to chemotherapy resistance in, for instance, hepatocellular carcinoma (Montero et al. 2008). The use of lovastatin, a cholesterol synthesis inhibitor, has also been shown to promote apoptosis in glioblastoma cell lines which the authors attributed to the increased level of Bim expression for apoptosis (Jiang et al. 2004). This indicates that biosynthesis of cholesterol has an indirect effect on the expression of activator Bim protein and thereby possibly regulating apoptosis.

Sphingolipid metabolism also contributes to MOMP, although its mechanism is not fully understood. Among the products of metabolism is ceramide which can form a channel in the membrane (Hannun and Obeid 2008). Sphingosine-1-PO4 (S1P) and hexadecanal (hex) which are ceramide precursors can mediate Bax/Bak activation through their synergistic activity leading to MOMP (Chipuk et al. 2012). Overall, CL has a direct interaction with Bcl-2 proteins whereas cholesterol and sphingolipid affect apoptosis indirectly through the metabolic pathways especially upon abnormalities occurring during the pathway.

Biophysical analysis of the apoptotic pore

Structural models of Bax/Bak oligomerization

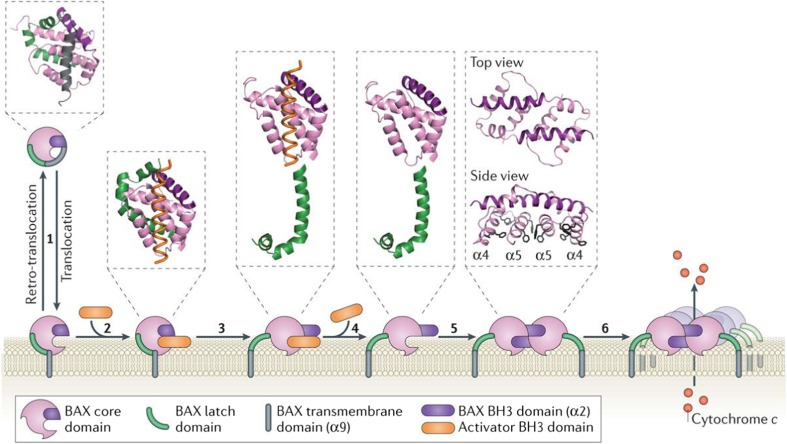

As discussed above, many Bcl-2 family proteins possess a hydrophobic region the carboxyl-terminus which is involved in membrane targeting and anchoring. The hydrophobic groove formed on the surface of the structure of the BH3 domain has a significant role especially with the interaction with another monomer of the Bcl-2 family for homo- and hetero-oligomerization leading to pore formation in the membrane. There are multiple steps involved in the Bax activation and oligomerization, and a current working model of Bax activation/pore formation based on the structural elucidation of Bax in different conformational states and complexes is shown in Fig. 4. However, the regulation of each of these steps remains elusive.

Fig. 4.

Overview of the conformational steps from the retrotranslocation of Bax to its activation and followed by its insertion into the membrane before it oligomerizes. 1 proposed shuttling of Bax to the MOM and return to the cytosol. 2 An activator BH3 domain binds to the BAX groove, which promotes release of the ‘latch’ domain from the ‘core’ domain of Bax (3), and destabilizes the Bax BH3 domain, α2. The initiating activator BH3 domain then disengages (4). 5 Protrusion of the Bax BH3 domain allows two such molecules to form the Bax BH3-in-groove dimer. The structure of the Bax core (α2–α5) as a symmetrical dimer reveals a hydrophobic layer of two α4 and two α5 chains with 12 protruding aromatic residues (side view) which then may form the larger oligomer (6). Reproduced with permission from Czabotar et al. (2014)

In a normal healthy cell, Bax is constitutively retro-translocated from mitochondria to the cytosol. This event is regulated by anti-apoptotic Bcl-xl whereby it maintains the inactive state of Bax (Edlich et al. 2011). In the presence of an apoptotic signal, Bid is cleaved into cBid and then into tBid to subsequently bind to Bax. tBid binds to the Bax ‘rear’ groove and this transient binding occurs via a ‘hit-and-run’ mechanism. Bax conformational changes involve the disengagement of tBid allowing for its insertion into the membrane (Wei et al. 2000). The previous study suggested Bax membrane insertion involved its α9 and hairpin α5–α6 helices (Annis et al. 2005) and are also suggested to participate in the pore formation (Garcia-Saez 2012). However, a recent study showed two interfaces involved in dimerization and pore expansion. Upon α9 membrane insertion, rearrangement of the helices resulted in the BH3-in-groove dimerization at the MOM surface. The α9 helix that transverses the membrane interacts with α9 of another monomer to cause the pore expansion (Zhang et al. 2015). These conformational changes were only able to be observed in the presence of membrane, thus emphasizing the importance of the membrane for the whole MOMP process.

The structure of the apoptotic pore

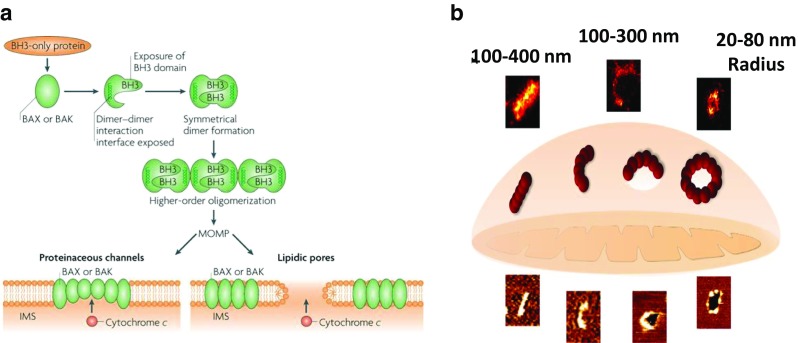

The pore formed by Bcl-2 proteins is the central structural entity mediating MOMP, but its precise structure has yet to be fully elucidated. However, a number of recent studies have used a combination of different imaging techniques to probe the formation and structure of the apoptotic pore in more detail than previously observed. Two different processes may lead to pore formation, namely via transmembrane oligomerization, or by insertion of their pore domain (Annis et al. 2005). The nature of the pore itself remains controversial as different studies propose that it is either proteinaceous or proteolipid (Fig. 5a). A small hydrophobic region in each of the protein monomers is involved in the oligomerization to provide a larger hydrophobic region which can then be inserted into the membrane (Ros and García-Sáez 2015). However, proteins such as colicin and diphtheria toxin of the pore-forming protein family can insert their central α-helical hairpin into the membrane and form a proteinaceous pore (Westphal et al. 2011). Bax and Bak have structural homology to colicin and diphtheria toxin in its α5 and α6 helices which can potentially insert into the membrane as a hairpin structure (Annis et al. 2005).

Fig. 5.

Model for the supramolecular organization of Bax at the MOM during apoptosis. a Formation of the apoptotic pore by active Bax or Bak where it can form a proteinaceous pore or lipidic pore. Dimerization occurs via the BH3 groove of each monomer (Tait and Green 2010). b Schematic showing the different shapes and size of the pores formed by Bax assemblies in the mitochondrial membrane revealed by SMLM and AFM during apoptosis. This study revealed the presence of linear and arc clusters that do not perforate the membrane, which lead to complete membrane pores, corresponding to full rings or partially arcs (Salvador-Gallego et al. 2016). Reproduced with permission from Salvador-Gallego et al. (2016 and Tait and Green (2010)

The lipidic pore is a heterogeneous pore as it consists of both protein and lipid components. Bax action on the phospholipid bilayer causes transbilayer movement (Terrones et al. 2004) and decreases the membrane stability facilitating membrane permeability (Basanez et al. 1999). A study by cryoelectron microscopy has shown potential lipidic pores formed by active Bax on cardiolipin-liposomes (Schafer et al. 2009). These pores vary in size which may reflect the expandable nature of the lipidic pore.

More recently, the presence of large ring-like structures formed by Bax oligomers on MOM was detected in apoptotic cells (Große et al. 2016; Salvador-Gallego et al. 2016) (Fig. 5b). These rings were able to perforate through the lipid bilayer, and they are devoid of other proteins (Große et al. 2016). Involvement of proteins other than Bax and Bak may assist in pore formation. Intriguingly, arc structures are also able to cause membrane permeabilization (Salvador-Gallego et al. 2016). The existence of different Bax organization in the membrane such as ring-like, lines and arcs structures indicate that the mechanistic details of Bax/Bak-mediated permeabilization are not entirely understood. However, these structures may represent various stages in Bax pore formation (Salvador-Gallego et al. 2016).

It has also been proposed that membrane-curvature stress induces Bax-mediated pore formation and subsequent MOMP (Gillies et al. 2015). In the toroidal pore, Bax/Bak localize and oligomerize at this site leading to pore formation whereby more Bax monomers enter and provide more curvature stress (Gillies et al. 2015).

Models of MOMP regulation

The Bcl-2 family of proteins interact in a complex system to regulate apoptosis and there are four main models that describe this regulation. The first model to be described is the direct activation model which suggests that BH3-only proteins activate pro-apoptotic proteins. Inhibition of apoptosis occurs upon sequestration of activator proteins by anti-apoptotic proteins (Chen et al. 2005; Chi et al. 2014). De-repressor BH3-only proteins displace the sequestered activators from the pro-survival protein such as Bcl-xl and Bcl-2, and this synergistic activity of both activators and sensitizers then allows the cells to undergo apoptosis (Kuwana et al. 2005).

The second model is the displacement model, which proposes the constitutive activation of pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and Bak within the cells which needs constant regulation by the anti-apoptotic proteins. BH3-only proteins compete with anti-apoptotic proteins to release Bax and Bak for apoptosis (Uren et al. 2007). Different BH3-only proteins bind to and neutralize the available pro-survival proteins during apoptosis via different binding affinity of each BH3-only protein (Zong et al. 2001). While these two models focus only on regulating the interaction between proteins, the third model, the so-called embedded-together model, proposes the explicit participation of the MOM (Leber et al. 2007, 2010; Shamas-Din et al. 2011). In particular, this model proposes that the mitochondrial membrane induces the conformational changes in the Bcl-2 proteins necessary for pore formation. This model has been widely used and places the membrane as the pivotal point for the activity of all Bcl-2 family proteins including the protein–protein and protein–membrane interactions required for apoptosis (Czabotar et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2016; Zong et al. 2001). Finally, a unified model has been described (Fig. 6) which further expands the embedded-together model by describing two distinct modes of activation whereby anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins can block MOMP, by sequestering direct-activator BH3-only proteins (i.e. Mode 1) or by binding active effector proteins Bax and Bak (i.e. Mode 2) (Llambi et al. 2011). These more recent models therefore establish a central role of the mitochondrial membrane in the regulation of apoptosis and have provided potential molecular targets for developing therapeutic intervention or activation of apoptosis.

Fig. 6.

Schematic overview of the unified model of the regulation of the Bcl-2 family proteins for apoptosis which builds on the embedded-together model, describing an explicit role of the membrane in apoptosis (Leber et al. 2007, 2010; Leber et al.; Shamas-Din et al. 2011). Reproduced with permission from Das et al. (2015)

Membrane binding properties of the C-terminal domain of Bcl-2 family proteins

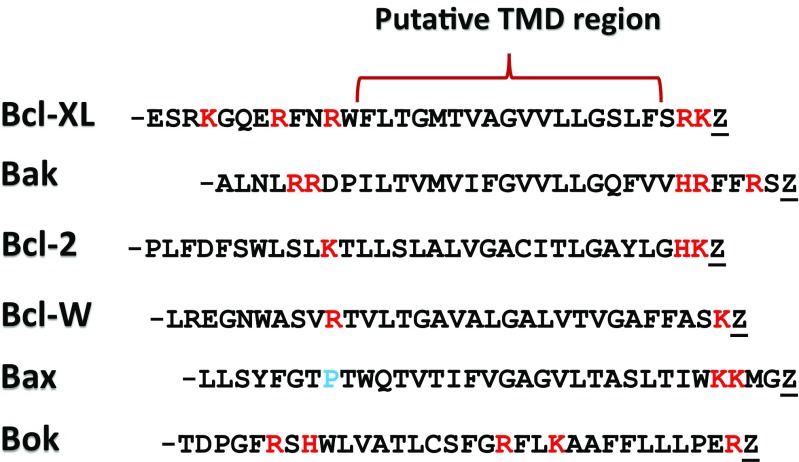

The interaction of Bcl-2 family members with specific lipids have been characterized on various model membranes. Some studies have particularly focussed on the putative TMD located at the C-terminal end of the protein family which has been shown to play a role in localisation of many Bcl-2 family members as listed in Fig. 7 (Andreu-Fernández et al. 2014; Lomonosova and Chinnadurai 2008; Shamas-Din et al. 2011; Youle and Strasser 2008).

Fig. 7.

Putative TMD sequence. Letters highlighted in red refer to polar amino acids, while the letter highlighted in blue refers to the regulatory proline in Bax. Z designates a stop codon. Adapted from Lindsay et al. (2011)

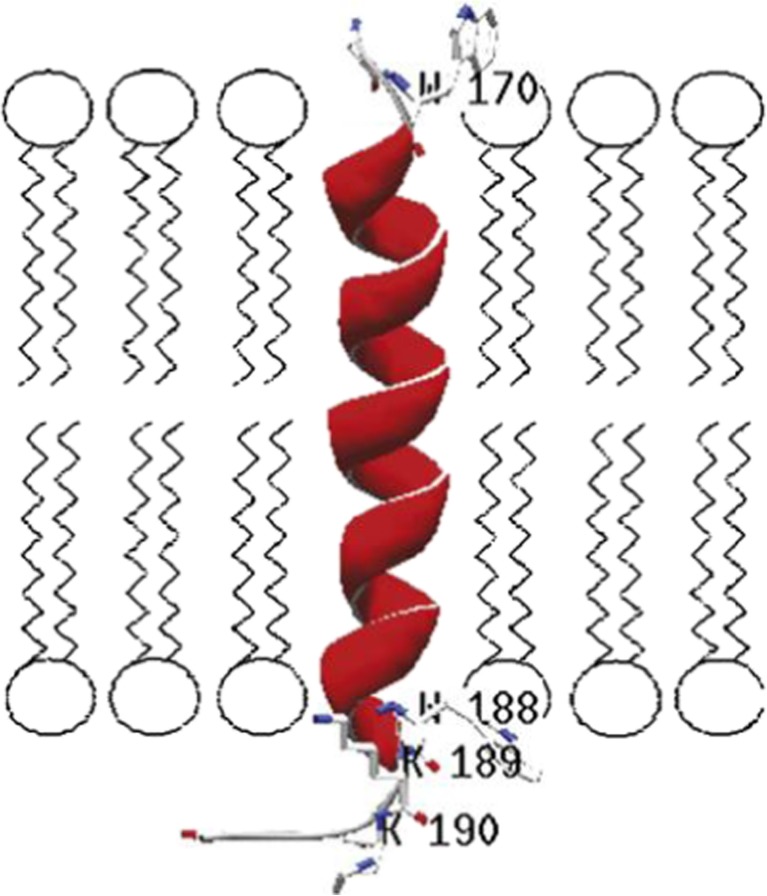

In comparison to the overall protein sequence, the region specified above (TMD) contains many hydrophobic residues in close proximity and were therefore hypothesized to be a TMD region. Potential membrane interacting regions can be identified by determining the hydrophobicity and hydrophobic moment (Bernabeu et al. 2007), and the putative TMD regions for different Bcl-2 family proteins are listed in Fig. 7. Model membranes have been utilized to characterize the protein–membrane interactions that occur between these TMD regions and specific phospholipid compositions. For example, the membrane interaction of the C-terminal region of Bcl-2 members was evident from the dye leakage from egg yolk PC liposomes composed of cholesterol, sphingomylin or egg yolk diacylglycerol upon the incubation of Bcl-2 TMD domain peptides (Torrecillas et al. 2007). Another study using the Bax C-terminus observed the changes in secondary structure in the TMD in different model membranes (Ausili et al. 2008). It was identified that a negative phospholipid environment induces changes in TMD secondary structure and the orientation of membrane insertion. It was demonstrated that a negative membrane environment induces Bax TMD to become more α-helical in structure, thought to be due to electrostatic interactions between lysine residues near the end of the sequence (see Fig. 3). Recent research from the same group has confirmed the interaction where insertion is believed to be perpendicular to the bilayer membrane (Ausili et al. 2009). Figure 8 illustrates this and shows that the interaction is assisted by tryptophan and lysine interaction with the polar head group. These studies have proven to be vital in understanding the protein–membrane interaction in model membranes; however, there is little available literature regarding testing of the Bcl-2 family on synthetic or isolated mitochondria outer membranes.

Fig. 8.

Orientation of Bax C-terminal peptide in a membrane. As can be seen, residues 170, 188 (tryptophan), 189 and 190 (Lysine) are thought to interact with the polar head groups of the lipids (Ausili et al. 2009)

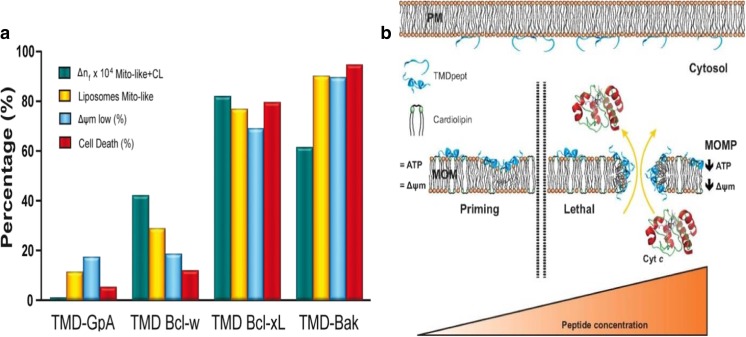

Peptides of the TMD of the Bcl-2 family have been synthesized and can be used as a starting point to resolve the secondary structure of the TMD region within the MOM. A study by Andreu-Fernández et al. (2014) specifically investigated the effects and kinetics of Bcl-2 family proteins binding to the MOM using peptides derived from the transmembrane domain (TMD) of the Bcl-2 family (Andreu-Fernández et al. 2014). The binding of synthetic peptides (TMD-pepts) corresponding to the putative TMD of anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bcl-w and Mcl-1) and pro-apoptotic (Bax, Bak) members to various model membranes and their impact on the membrane packing order were studied using dual polarization interferometry. The results demonstrated that the peptides showed specificity for mitochondrial membrane mimics over plasma membrane mimics. Significantly, the peptides exerted different effects on membrane structure depending on whether they were derived from pro- or anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members (Fig. 9a) and they promoted calcein release from liposomes via disrupting the order of the model mitochondrial lipid system. These results were then correlated with cellular disruption effects. In particular, the TMDs induced permeabilisation and cytochrome c release from isolated mitochondria, were cytotoxic toward the human cervix adenocarcinoma cell line and colon carcinoma cell line and were effective as chemical tools to prepare mitochondria for apoptosis as demonstrated by sensitizing human cervix adenocarcinoma cells to chemotherapeutic agents. Overall, the observed effects of the TMD-peptides on membrane perturbation open the way for their use as new chemical tools to sensitize tumour cells to chemotherapeutic agents, in accordance with the concept of mitochondria priming (Fig. 9b) (Andreu-Fernández et al. 2014). More recently, it has been shown that interactions between the TMD of Bax and pro-survival Bcl-x also occur in non-apoptotic human cells and participate in the regulation of Bcl-2 proteins, further establishing the central role of the TMD in the regulation of apoptosis (Andreu-Fernandez et al. 2017).

Fig. 9.

Interaction of TMD peptides derived from Bcl-2 proteins with model and native mitochondrial membranes. a Summary of mitochondrial membrane binding. b Schematic depicting a model for mitochondrial membrane priming by the TMD peptides. Reproduced with permission from Andreu-Fernández et al. (2014)

The importance of studying protein activity at the membrane level was further demonstrated by a recent study by Zhang et al. (2015). A new interface for Bax dimerization was identified which occurs via the α9:α9 helices within the membrane apart from the BH3:groove interface found on the surface, which was shown to be crucial for pore expansion (Zhang et al. 2015). From this study, the discovery of another feature required for Bax dimerization has demonstrated that studies on the dynamics of protein structure and interactions are required to fully understand apoptosis at the dynamic membrane interface.

Conclusions

The mitochondrion plays a central role in apoptosis and is the site of recruitment for apoptotic proteins controlling the intrinsic apoptotic pathway leading to MOMP. The Bcl-2 family of proteins play a commanding role in the regulation of MOMP, and the membrane involvement in this complex system is now well recognized. An increasing number of studies have clearly shown that the mitochondrial outer membrane plays a central role in apoptosis. These studies have shed light on the structural changes of the Bcl-2 family during their activation, membrane-insertion and oligomerization as well as the interactions between Bcl-2 family members during apoptosis. Indeed, these studies have led to the identification of new drug targets and underpinned the development of inhibitors of Bcl-2 protein interactions as potential anti-cancer therapeutics. However, there are still relatively few studies that focus specifically on the biophysical analysis of the protein–membrane interactions in the context of membrane structure changes. It is now apparent that members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins insert into the mitochondrial outer membrane through a specific C-terminal anchoring transmembrane domain, and then interact hierarchically to determine cell fate. These studies now pave the way for the analysis of the interaction of full-length protein with the mitochondrial membrane and provide answers to a number of important questions addressing the mechanism of how Bcl-2 proteins are recruited to the membrane prior to the initiation of MOMP. For example, what are the relative binding affinities of these proteins to the mitochondrial membrane and, following the membrane recruitment, how does the membrane environment and changing lipid compositions mediate the step-by-step conformational changes of the Bcl-2 proteins, and how does the membrane structure change throughout these critical events? Understanding these critical events in the interplay between Bcl-2 family proteins and MOM will provide significant insight into how MOMP is initiated and regulated, and establish a more detailed understanding of the interplay between anti- and pro-apoptotic proteins and the role that the mitochondrial membrane plays in this process.

Acknowledgements

The financial support of the National Health & Medical Research Council (#1084648) is gratefully acknowledged.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

Siti Haji Suhaili declares that she has no conflicts of interest. Hamed Karimian declares that he has no conflicts of interest. Matthew Stellato declares that he has no conflicts of interest. Tzong-Hsien Lee declares that he has no conflicts of interest. Marie-Isabel Aguilar declares that she has no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Siti Haji Suhaili and Hamed Karimian contributed equally to this work

This article is part of a Special Issue on ‘IUPAB Edinburgh Congress’ edited by Damien Hall.

References

- Adams J. The development of proteasome inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:417–421. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreu-Fernández V, Genoves A, Lee T-H, Stellato M, Lucantoni F, Orzáez M, Mingarro I, Aguilar M-I, Pérez-Payá E. Peptides derived from the transmembrane domain of bcl-2 proteins as potential mitochondrial priming tools. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1799–1811. doi: 10.1021/cb5002679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreu-Fernandez V, Sancho M, Genoves A, Lucendo E, Todt F, Lauterwasser J, Funk K, Jahreis G, Perez-Paya E, Mingarro I, Edlich F, Orzaez M. Bax transmembrane domain interacts with prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins in biological membranes. Proc Natl Acad of Sci U S A. 2017;114:310–315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612322114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annis MG, Soucie EL, Dlugosz PJ, Cruz-Aguado JA, Penn LZ, Leber B, Andrews DW. Bax forms multispanning monomers that oligomerize to permeabilize membranes during apoptosis. EMBO J. 2005;24:2096–2103. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardail D, Privat J, Egret-Charlier M, Levrat C, Lerme F, Louisot P. Mitochondrial contact sites. Lipid composition and dynamics. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18797–18802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausili A, Torrecillas A, Martínez-Senac MM, Corbalán-García S, Gómez-Fernández JC. The interaction of the Bax C-terminal domain with negatively charged lipids modifies the secondary structure and changes its way of insertion into membranes. J Struct Biol. 2008;164:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausili A, de Godos A, Torrecillas A, Corbalán-García S, Gómez-Fernández JC. The interaction of the Bax C-terminal domain with membranes is influenced by the presence of negatively charged phospholipids. Biochim Biophysica Acta-Biomembr. 2009;1788:1924–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines CP, Kaiser RA, Sheiko T, Craigen WJ, Molkentin JD. Voltage-dependent anion channels are dispensable for mitochondrial-dependent cell death. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:550–555. doi: 10.1038/ncb1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basanez G, Nechushtan A, Drozhinin O, Chanturiya A, Choe E, Tutt S, Wood K, Hsu Y-T, Zimmerberg J, Youle R. Bax, but not Bcl-xL, decreases the lifetime of planar phospholipid bilayer membranes at subnanomolar concentrations. Proc Natl Acad of Sci U S A. 1999;96:5492–5497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergelson L, Dyatlovitskaya E, Torkhovskaya T, Sorokina I, Gorkova N. Phospholipid composition of membranes in the tumor cell. Biochim Biophys Acta-lipids and lipid. Metabolism. 1970;210:287–298. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(70)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernabeu A, Guillén J, Pérez-Berná AJ, Moreno MR, Villalaín J. Structure of the C-terminal domain of the pro-apoptotic protein Hrk and its interaction with model membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta-Biomembr. 2007;1768:1659–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billen LP, Kokoski CL, Lovell JF, Leber B, Andrews DW. Bcl-XL inhibits membrane permeabilization by competing with Bax. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleicken S, Hofhaus G, Ugarte-Uribe B, Schröder R, García-Sáez A. cBid, Bax and Bcl-xL exhibit opposite membrane remodeling activities. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2121. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge DG, Xue D. Regulation of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization by BCL-2 family proteins and caspases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:647–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Attardi LD. The role of apoptosis in cancer development and treatment response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nrc1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürgermeister M, Birner-Grünberger R, Nebauer R, Daum G. Contribution of different pathways to the supply of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine to mitochondrial membranes of the yeast Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2004;1686:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Certo M, Del Gaizo MV, Nishino M, Wei G, Korsmeyer S, Armstrong SA, Letai A. Mitochondria primed by death signals determine cellular addiction to antiapoptotic BCL-2 family members. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:351–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Willis SN, Wei A, Smith BJ, Fletcher JI, Hinds MG, Colman PM, Day CL, Adams JM, Huang DC. Differential targeting of prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins by their BH3-only ligands allows complementary apoptotic function. Mol Cell. 2005;17:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Feldstein AE, McIntyre TM. Suppression of mitochondrial function by oxidatively truncated phospholipids is reversible, aided by bid, and suppressed by Bcl-XL. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26297–26308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HC, Kanai M, Inoue-Yamauchi A, Tu HC, Huang Y, Ren D, Kim H, Takeda S, Reyna DE, Chan PM, Ganesan YT, Liao CP, Gavathiotis E, Hsieh JJ, Cheng EH. An interconnected hierarchical model of cell death regulation by the BCL-2 family. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1270–1281. doi: 10.1038/ncb3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng EH-Y, Sheiko TV, Fisher JK, Craigen WJ, Korsmeyer SJ. VDAC2 inhibits BAK activation and mitochondrial apoptosis. Science. 2003;301:513–517. doi: 10.1126/science.1083995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi X, Kale J, Leber B, Andrews DW. Regulating cell death at, on, and in membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Res. 2014;1843:2100–2113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk JE, Fisher JC, Dillon CP, Kriwacki RW, Kuwana T, Green DR. Mechanism of apoptosis induction by inhibition of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins. Proc Natl Acad of Sci U S A. 2008;105:20327–20332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808036105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk JE, Moldoveanu T, Llambi F, Parsons MJ, Green DR. The BCL-2 family reunion. Mol Cell. 2010;37:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk JE, McStay GP, Bharti A, Kuwana T, Clarke CJ, Siskind LJ, Obeid LM, Green DR. Sphingolipid metabolism cooperates with BAK and BAX to promote the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 2012;148:988–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou JJ, Li H, Salvesen GS, Yuan J, Wagner G. Solution structure of BID, an intracellular amplifier of apoptotic signaling. Cell. 1999;96:615–624. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson E, Merlin S, Saito M, Schlesinger P. Cholesterol effects on BAX pore activation. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:1168–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbeau A, Nachbaur J, Vignais P. Enzymac characterization and lipid composition of rat liver subcellular membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta-Biomembr. 1971;249:462–492. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(71)90123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino K, García-Sáez AJ. Mitochondrial alterations in apoptosis. Chem Phys Lipids. 2014;181:62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino K, Garcia-Saez AJ. Bax and Bak pores: are we closing the circle? Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimi M, Degli Esposti M. Apoptosis-induced changes in mitochondrial lipids. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Res. 2011;1813:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czabotar PE, Lee EF, Thompson GV, Wardak AZ, Fairlie WD, Colman PM. Mutation to Bax beyond the BH3 domain disrupts interactions with pro-survival proteins and promotes apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7123–7131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.161281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czabotar PE, Lessene G, Strasser A, Adams JM. Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family: implications for physiology and therapy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:49–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das KK, Unsay JD, Garcia-Saez AJ. Microscopy of model membranes: understanding how Bcl-2 proteins mediate apoptosis. Adv Planar Lipid Bilayers Liposomes. 2015;21:63–97. [Google Scholar]

- Degli Esposti M, Cristea I, Gaskell S, Nakao Y, Dive C. Proapoptotic bid binds to monolysocardiolipin, a new molecular connection between mitochondrial membranes and cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:1300–1309. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejean LM, Martinez-Caballero S, Guo L, Hughes C, Teijido O, Ducret T, Ichas F, Korsmeyer SJ, Antonsson B, Jonas EA. Oligomeric Bax is a component of the putative cytochrome c release channel MAC, mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2424–2432. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingeldein APG, Pokorná Š, Lidman M, Sparrman T, Šachl R, Hof M, Gröbner G. Apoptotic Bax at Oxidatively stressed mitochondrial membranes: lipid dynamics and Permeabilization. Biophys J. 2017;112:2147–2158. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlich F, Banerjee S, Suzuki M, Cleland MM, Arnoult D, Wang C, Neutzner A, Tjandra N, Youle RJ. Bcl-x L retrotranslocates Bax from the mitochondria into the cytosol. Cell. 2011;145:104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskes R, Desagher S, Antonsson B, Martinou JC. Bid induces the oligomerization and insertion of Bax into the outer mitochondrial membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:929–935. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.929-935.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda S, Debatin K. Extrinsic versus intrinsic apoptosis pathways in anticancer chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2006;25:4798–4811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcea R, Canuto R, Gautero B, Biocca M, Feo F. Phospholipid composition of inner and outer mitochondrial membranes isolated from Yoshida hepatoma AH-130. Cancer Lett. 1980;11:133–139. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(80)90104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Saez A. The secrets of the Bcl-2 family. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1733–1740. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Sáez AJ, Buschhorn SB, Keller H, Anderluh G, Simons K, Schwille P. Oligomerization and pore formation by equinatoxin II inhibit endocytosis and lead to plasma membrane reorganization. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:37768–37777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.281592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavathiotis E, Suzuki M, Davis ML, Pitter K, Bird GH, Katz SG, Tu H-C, Kim H, Cheng EH-Y, Tjandra N. BAX activation is initiated at a novel interaction site. Nature. 2008;455:1076–1081. doi: 10.1038/nature07396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies LA, Du H, Peters B, Knudson CM, Newmeyer DD, Kuwana T. Visual and functional demonstration of growing Bax-induced pores in mitochondrial outer membranes. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:339–349. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-11-0638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloster J, Harris P. The lipid composition of mitochondrial and microsomal fractions from human ventricular myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1970;1:459–465. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(70)90042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, Yin X-M, Wang K, Wei MC, Jockel J, Milliman C, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Korsmeyer SJ. Caspase cleaved BID targets mitochondria and is required for cytochrome c release, while BCL-XL prevents this release but not tumor necrosis factor-R1/Fas death. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1156–1163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Große L, Wurm CA, Brüser C, Neumann D, Jans DC, Jakobs S. Bax assembles into large ring-like structures remodeling the mitochondrial outer membrane in apoptosis. EMBO J. 2016;35:402–413. doi: 10.15252/embj.201592789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:139–150. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath SE, Daum G. Lipids of mitochondria. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52:590–614. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovius R, Lambrechts H, Nicolay K, de Kruijff B. Improved methods to isolate and subfractionate rat liver mitochondria. Lipid composition of the inner and outer membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta-Biomembr. 1990;1021:217–226. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(90)90036-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichim G, Tait SW. A fate worse than death: apoptosis as an oncogenic process. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:539–548. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Zheng X, Lytle RA, Higashikubo R, Rich KM. Lovastatin-induced up-regulation of the BH3-only protein, Bim, and cell death in glioblastoma cells. J Neurochem. 2004;89:168–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdain A, Martinou J-C. Mitochondrial outer-membrane permeabilization and remodelling in apoptosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1884–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan VE, Tyurin VA, Jiang J, Tyurina YY, Ritov VB, Amoscato AA, Osipov AN, Belikova NA, Kapralov AA, Kini V. Cytochrome c acts as a cardiolipin oxygenase required for release of proapoptotic factors. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:223–232. doi: 10.1038/nchembio727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantari C, Walczak H. Caspase-8 and bid: caught in the act between death receptors and mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Res. 2011;1813:558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch J, Molkentin JD. Identifying the components of the elusive mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Proc Natl Acad of Sci U S A. 2014;111:10396–10397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410104111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann SH, Hengartner MO. Programmed cell death: alive and well in the new millennium. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:526–534. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Tu H-C, Ren D, Takeuchi O, Jeffers JR, Zambetti GP, Hsieh JJ-D, Cheng EH-Y. Stepwise activation of BAX and BAK by tBID, BIM, and PUMA initiates mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2009;36:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland RA, Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF, Franklin JL. Loss of cardiolipin and mitochondria during programmed neuronal death: evidence of a role for lipid peroxidation and autophagy. Neuroscience. 2002;115:587–602. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00512-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnareva Y, Andreyev AY, Kuwana T, Newmeyer DD. Bax activation initiates the assembly of a multimeric catalyst that facilitates Bax pore formation in mitochondrial outer membranes. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, Chipuk JE, Bonzon C, Sullivan BA, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. BH3 domains of BH3-only proteins differentially regulate Bax-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization both directly and indirectly. Mol Cell. 2005;17:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leber B, Lin J, Andrews DW. Embedded together: the life and death consequences of interaction of the Bcl-2 family with membranes. Apoptosis. 2007;12:897–911. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0746-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leber B, Lin J, Andrews D. Still embedded together binding to membranes regulates Bcl-2 protein interactions. Oncogene. 2010;29:5221–5230. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EF, Grabow S, Chappaz S, Dewson G, Hockings C, Kluck RM, Debrincat MA, Gray DH, Witkowski MT, Evangelista M. Physiological restraint of Bak by Bcl-xL is essential for cell survival. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1240–1250. doi: 10.1101/gad.279414.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letai A, Bassik MC, Walensky LD, Sorcinelli MD, Weiler S, Korsmeyer SJ. Distinct BH3 domains either sensitize or activate mitochondrial apoptosis, serving as prototype cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Yuan J. Caspases in apoptosis and beyond. Oncogene. 2008;27:6194–6206. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay J, Degli Esposti M, Gilmore AP. Bcl-2 proteins and mitochondria—specificity in membrane targeting for death. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Res. 2011;1813:532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llambi F, Moldoveanu T, Tait SW, Bouchier-Hayes L, Temirov J, McCormick LL, Dillon CP, Green DR. A unified model of mammalian BCL-2 protein family interactions at the mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2011;44:517–531. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomonosova E, Chinnadurai G. BH3-only proteins in apoptosis and beyond: an overview. Oncogene. 2008;27:S2–S19. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucken-Ardjomande S, Montessuit S, Martinou J-C. Bax activation and stress-induced apoptosis delayed by the accumulation of cholesterol in mitochondrial membranes. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:484–493. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucken-Ardjomande S, Montessuit S, Martinou J-C. Contributions to Bax insertion and oligomerization of lipids of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:929–937. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter M, Fang M, Luo X, Nishijima M, Xie X-s, Wang X. Cardiolipin provides specificity for targeting of tBid to mitochondria. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:754–761. doi: 10.1038/35036395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinou J-C, Youle RJ. Mitochondria in apoptosis: Bcl-2 family members and mitochondrial dynamics. Dev Cell. 2011;21:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsko CM, Hunter OC, Rabinowich H, Lotze MT, Amoscato AA. Mitochondrial lipid alterations during Fas-and radiation-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2001;287:1112–1120. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero J, Morales A, Llacuna L, Lluis JM, Terrones O, Basañez G, Antonsson B, Prieto J, García-Ruiz C, Colell A. Mitochondrial cholesterol contributes to chemotherapy resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5246–5256. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchmore SW, Sattler M, Liang H, Meadows RP, Harlan JE, Yoon HS, Nettesheim DG, Chang BS, Thompson CB, Wong S-L. X-ray and NMR structure of human Bcl-xL, an inhibitor of programmed cell death. Nature. 1996;381:335–341. doi: 10.1038/381335a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh KJ, Barbuto S, Meyer N, Kim R-S, Collier RJ, Korsmeyer SJ. Conformational changes in BID, a pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family member, upon membrane binding a SITE-DIRECTED SPIN LABELING STUDY. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:753–767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405428200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S, Yang C, Li S, Xu C, Zhao Y, Ren H. Smac: its role in apoptosis induction and use in lung cancer diagnosis and treatment. Cancer Lett. 2012;318:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros U, García-Sáez AJ. More than a pore: the interplay of pore-forming proteins and lipid membranes. J Membr Biol. 2015;248:545–561. doi: 10.1007/s00232-015-9820-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytömaa M, Mustonen P, Kinnunen P. Reversible, nonionic, and pH-dependent association of cytochrome c with cardiolipin-phosphatidylcholine liposomes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22243–22248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-Gallego R, Mund M, Cosentino K, Schneider J, Unsay J, Schraermeyer U, Engelhardt J, Ries J, García-Sáez AJ. Bax assembly into rings and arcs in apoptotic mitochondria is linked to membrane pores. EMBO J. 2016;35:389–401. doi: 10.15252/embj.201593384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satsoura D, Kučerka N, Shivakumar S, Pencer J, Griffiths C, Leber B, Andrews DW, Katsaras J, Fradin C. Interaction of the full-length Bax protein with biomimetic mitochondrial liposomes: a small-angle neutron scattering and fluorescence study. Biochim Biophys Acta-Biomembr. 2012;1818:384–401. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler M, Liang H, Nettesheim D, Meadows RP, Harlan JE, Eberstadt M, Yoon HS, Shuker SB, Chang BS, Minn AJ. Structure of Bcl-xL-Bak peptide complex: recognition between regulators of apoptosis. Science. 1997;275:983–986. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer B, Quispe J, Choudhary V, Chipuk JE, Ajero TG, Du H, Schneiter R, Kuwana T. Mitochondrial outer membrane proteins assist bid in Bax-mediated lipidic pore formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2276–2285. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlame M, Rua D, Greenberg ML. The biosynthesis and functional role of cardiolipin. Prog Lipid Res. 2000;39:257–288. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(00)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamas-Din A, Brahmbhatt H, Leber B, Andrews DW. BH3-only proteins: orchestrators of apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Res. 2011;1813:508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamas-Din A, Bindner S, Chi X, Leber B, Andrews DW, Fradin C. Distinct lipid effects on tBid and Bim activation of membrane permeabilization by pro-apoptotic Bax. Biochem J. 2015;467:495–505. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivakumar S, Kurylowicz M, Hirmiz N, Manan Y, Friaa O, Shamas-Din A, Masoudian P, Leber B, Andrews DW, Fradin C. The proapoptotic protein tBid forms both superficially bound and membrane-inserted oligomers. Biophys J. 2014;106:2085–2095. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Youle RJ, Tjandra N. Structure of Bax: coregulation of dimer formation and intracellular localization. Cell. 2000;103:645–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait SW, Green DR. Mitochondria and cell death: outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:621–632. doi: 10.1038/nrm2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrones O, Antonsson B, Yamaguchi H, Wang H-G, Liu J, Lee RM, Herrmann A, Basañez G. Lipidic pore formation by the concerted action of proapoptotic BAX and tBID. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30081–30091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313420200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrecillas A, Martínez-Senac MM, Ausili A, Corbalán-García S, Gómez-Fernández JC. Interaction of the C-terminal domain of Bcl-2 family proteins with model membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta-Biomembr. 2007;1768:2931–2939. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyurin VA, Tyurina YY, Kochanek PM, Hamilton R, DeKosky ST, Greenberger JS, Bayir H, Kagan VE. Chapter nineteen oxidative lipidomics of programmed cell death. Methods Enzymol. 2008;442:375–393. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)01419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uren RT, Dewson G, Chen L, Coyne SC, Huang DC, Adams JM, Kluck RM. Mitochondrial permeabilization relies on BH3 ligands engaging multiple prosurvival Bcl-2 relatives, not Bak. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:277–287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei MC, Lindsten T, Mootha VK, Weiler S, Gross A, Ashiya M, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. tBID, a membrane-targeted death ligand, oligomerizes BAK to release cytochrome c. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2060–2071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal D, Dewson G, Czabotar PE, Kluck RM. Molecular biology of Bax and Bak activation and action. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Res. 2011;1813:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal D, Kluck R, Dewson G. Building blocks of the apoptotic pore: how Bax and Bak are activated and oligomerize during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:196–205. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong RS. Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:87. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-30-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yethon JA, Epand RF, Leber B, Epand RM, Andrews DW. Interaction with a membrane surface triggers a reversible conformational change in Bax normally associated with induction of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48935–48941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youle RJ, Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaltsman Y, Shachnai L, Yivgi-Ohana N, Schwarz M, Maryanovich M, Houtkooper RH, Vaz FM, De Leonardis F, Fiermonte G, Palmieri F. MTCH2/MIMP is a major facilitator of tBID recruitment to mitochondria. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:553–562. doi: 10.1038/ncb2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Subramaniam S, Kale J, Liao C, Huang B, Brahmbhatt H, Condon SG, Lapolla SM, Hays FA, Ding J (2015) BH3-in-groove dimerization initiates and helix 9 dimerization expands Bax pore assembly in membranes. EMBO J 35:208–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zong W-X, Lindsten T, Ross AJ, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB. BH3-only proteins that bind pro-survival Bcl-2 family members fail to induce apoptosis in the absence of Bax and Bak. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1481–1486. doi: 10.1101/gad.897601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]