Abstract

Two broadleaf evergreen canopy species (Schima superba and Engelhardia roxburghiana) with different phenologies in a subtropical region of southern China were used to determine the influence of leaf phenology on the impact of an insect pest attack. S. superba regenerates its leaves in February, while E. roxburghiana regenerates its leaves in May. The moth Thalassodes quadraria attacked the two broadleaf evergreen species in March to April, and the newly produced leaves were removed for S. superba but not for E. roxburghiana. The young trees were artificially defoliated to imitate an insect pest attack during March 2014. Nonstructural carbohydrate (NSC) and growth measurements and a retrospective analysis based on the radial growth of mature trees were conducted in January 2015. The results showed that NSC concentrations decreased in S. superba during canopy rebuilding, and the subsequent defoliation severely inhibited leaf and shoot growth, prevented NSC restoration in roots and stem xylem, and caused high mortality. The insect outbreaks reduced the radial growth of S. superba. In contrast, E. roxburghiana experienced less growth retardation, lower mortality, and normal radial growth. Thus, taking phenology-dependent variation in NSCs into consideration, defoliation and insect pest outbreaks more negatively impacted S. superba than E. roxburghiana.

Introduction

In recent years, forest mortality has increased on a global scale. This phenomenon has been attributed to the drought and drought-induced pest attacks associated with climate change1, 2. Regardless of the type of stressor involved, amounts of nonstructural carbohydrates (NSCs), which provide energy for plant growth and the maintenance of life, are likely to decrease, thereby disturbing the equilibrium between plant carbon uptake and utilization. This imbalance can result in plant death3. The leaf is the photosynthesis apparatus that produces carbohydrates, including NSCs. Defoliation by any means, including insect predation, will decrease plant host carbon uptake and thereby likely reduce its carbon storage. In general, moderate and severe defoliation cause reductions in NSC concentrations4–6. In some cases, the fast recovery of NSC stores after defoliation has been reported7–9. Nevertheless, the impact of insect herbivore defoliation varies with the host plant type10, growth stage11, 12 and nitrogen content and expansion rate of young leaves13, 14.

Leaf phenology has been shown to influence plant host resistance to insect predation due to relative differences in foliage chemical composition15 and toughness16. Phenological asynchrony between budburst and the emergence of larvae can function as an effective mechanism by which plants can protect themselves against defoliating insects that are active in springtime, when the leaves newly emerge and are relatively vulnerable11. However, to our knowledge, it remains unknown whether phenology-dependent variation in tree NSC concentrations influences the impact of insect pest predation. It is well known that carbon reserves vary among different tree phenological events17, 18 and that the lowest NSC concentrations occur during canopy rebuilding, especially in branches17. Carbohydrate reserves play a critical role in tree survival under stress situations19, 20, including tolerance to biotic agents3. Biotic attack may amplify, or be amplified by, carbon starvation3. However, declining carbohydrate reserves could also cause hydraulic failure through the impaired refilling of embolized conduits21, 22 and be vulnerable to water deficit. Forest decline is frequently ascribed to the combined effects of drought and pest damage1, 3.

A typical natural monsoon evergreen broadleaved forest is the climax vegetation in the subtropical region of the Dinghu Mountains located in central Guangdong, southern China. In recent years, insect pest outbreaks have frequently occurred in the Dinghu Mountains23, 24. Severe attacks of the moth Thalassodes quadraria Guene occurred in this region during 1985–198923 and 2012–2013. After the 2012–2013 infestation, one dominant canopy species, Schima superba Gardn. et Champ., suffered high mortality, whereas the mortality of another dominant canopy species, Engelhardia roxburghiana Wall., was significantly lower despite the fact that the severity of the insect pest attacks on both tree species was similar. The Dinghu Mountain region has a typical monsoon climate with a distinct dry season from October to March. Insects frequently emerge there in early spring (March to April). Since 1980, the mean air temperatures in southern China have gone up, and rainfall patterns have shifted towards more severe storms during the wet season, more rain-free days during the year and fewer days per year with light rain. Total rainfall, however, has not significantly changed25. Both S. superba and E. roxburghiana are broadleaved evergreen species. S. superba regenerates its leaves each February, whereas E. roxburghiana produces its foliage in May26 (Supplemental Fig. 1). Therefore, S. superba renews its leaves just before the insect outbreak, whilst E. roxburghiana renews them after insect emergence.

We hypothesize that (1) variation in nonstructural carbohydrates (NSCs) with the phenology cycle play an important role in the differential responses of S. superba and E. roxburghiana to insect pest attacks, and (2) the differential responses of the two species to insect pest attacks may also be related to the interaction between carbon source limitation caused by the insect predation and water deficit in the dry season. Canopy rebuilding consumes much of the carbohydrate reserves, and if the new leaves are immediately defoliated by pests, the plants could face carbon starvation. However, the declining carbohydrate reserves could also cause hydraulic failure through the impaired refilling of embolized conduits in the dry season. To test these hypotheses, we carried out an artificial defoliation experiment simulating an insect attack. Before and after the defoliation of young trees, the nonstructural carbohydrate content in different tissues was measured. The growth rates, gas exchange, and water relations were analysed after defoliation. In addition, a retrospective analysis based on the ring growth of mature trees was conducted to measure radial growth responses to the insect outbreaks. Tree ring analysis has proven to be a suitable tool for measuring growth reduction, and it serves as an indicator of previous environmental stress and insect attacks27.

Results

Impact of defoliation on growth

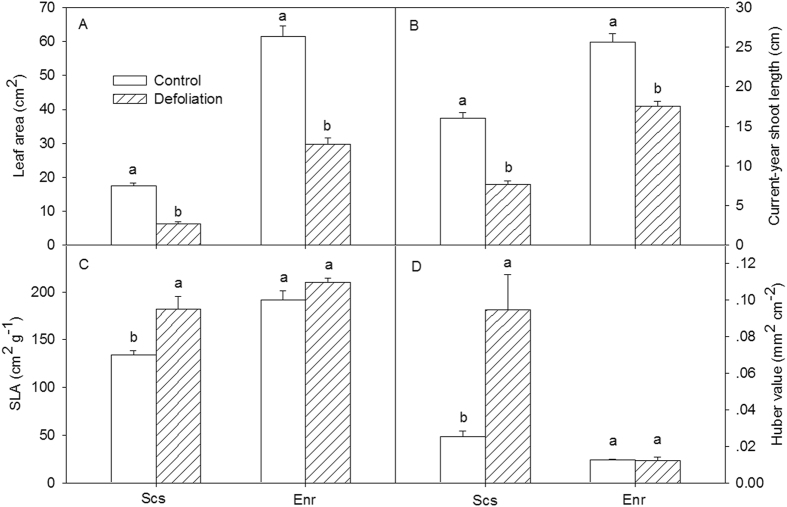

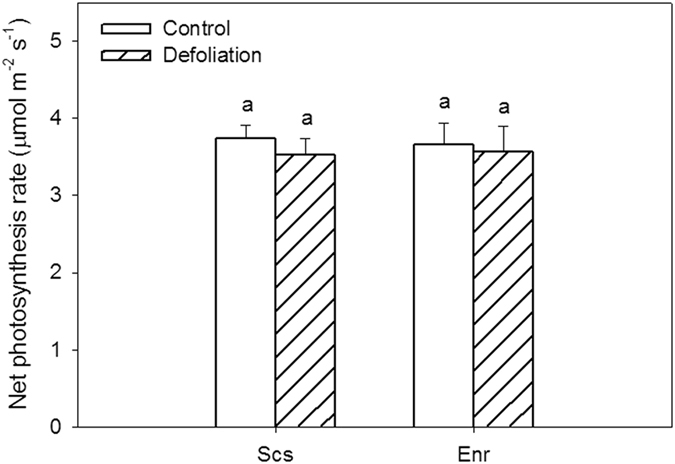

Defoliation significantly reduced newly grown leaf size and current-year shoot length in both species (Fig. 1A,B). The leaf size and shoot length of defoliated S. superba were reduced by 64.2% and 52% in comparison to the control (p < 0.01), respectively, while those of the defoliated E. roxburghiana decreased by 51.7% and 31.7% in comparison to the control (p < 0.01), respectively. There were significant interactions between species and treatment (p < 0.01). These findings indicate that the adverse effects of defoliation on the leaf size and shoot length were more severe in S. superba than in E. roxburghiana. Defoliation significantly increased both the specific leaf area (SLA) and the Huber value (Hv) of S. superba (p < 0.01) but did not change those of E. roxburghiana (p = 0.67) (Fig. 1C,D). The Hv of defoliated S. superba was 3.72 times greater than that of the control. The SLA and Hv data indicate that the leaf dry matter and the total leaf area per unit sapwood area of defoliated S. superba were still lower than those of the control even ten months after defoliation. Nevertheless, there were no significant differences (p > 0.60) between the defoliation treatment and the control for either tree species in terms of net photosynthetic rate (Pn) per unit leaf area (Fig. 2). However, the total assimilation per tree was much lower in the defoliated S. superba than in the control because the total leaf area of the defoliated treatment was significantly reduced compared to that of the control.

Figure 1.

(A) Leaf size, (B) current-year shoot length, (C) specific leaf area, and (D) Huber value for control and defoliated Schima superba (Scs) and Engelhardia roxburghiana (Enr). The mean ± SE is presented (n = 3–6), and different letters above the bars indicate significant differences in the values at P = 0.05.

Figure 2.

Net photosynthetic rates of Schima superba (Scs) and Engelhardia roxburghiana (Enr). The mean ± SE is presented (n = 3–6), and different letters indicate a significant difference in the net photosynthetic rates at P = 0.05.

Impact of defoliation on survival

Three of the six defoliated young S. superba trees died off within ten months, whereas all six defoliated young E. roxburghiana trees survived. All of the control trees from both species survived.

Impact of defoliation on NSCs in different tissues

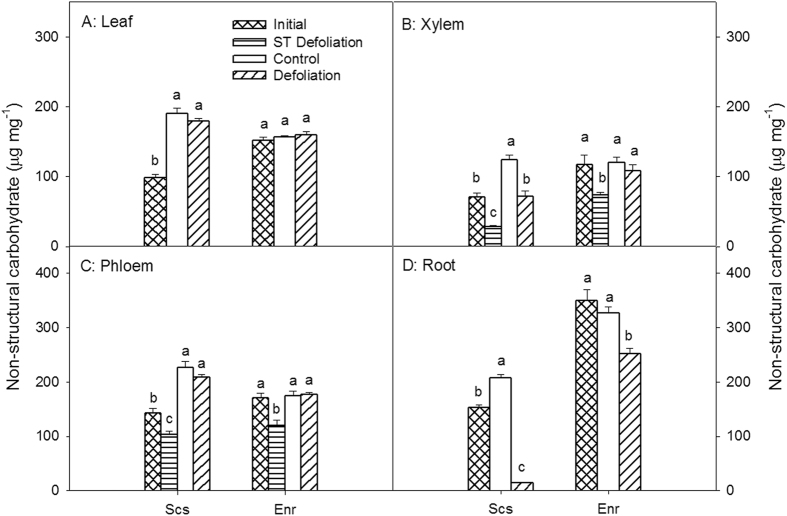

The total nonstructural carbohydrate (NSC) concentrations in the S. superba leaves, xylem, phloem and roots sampled in March 2014 (when leaf renewal was completed and just before the defoliation treatment) were all significantly lower than those of the control samples collected in January 2015 (p < 0.01), prior to the next cycle of leaf renewal. There were no significant differences in NSC concentrations among E. roxburghiana organs and tissues collected between March 2014 and January 2015 (p > 0.85) (Fig. 3). The defoliated S. superba had significantly lower NSC concentrations in xylem and roots than the control (p < 0.01); the NSC concentrations in the roots of the defoliated S. superba were only 6.6% that of the control. There were no significant differences in leaf (p = 0.96) and stem phloem (p = 0.88) NSC concentrations between defoliated and control S. superba. The NSC concentrations of leaves, xylem and phloem from the defoliated E. roxburghiana were not significantly different from those of the control (p > 0.95). Only the NSC concentration in the roots of defoliated E. roxburghiana was significantly lower than that of the control (p = 0.024). However, the absolute NSC concentration in the roots of defoliated E. roxburghiana was much higher than that of defoliated S. superba (p < 0.01).

Figure 3.

Nonstructural carbohydrate (NSC) concentrations in leaves, xylem, phloem, and roots of Schima superba (Scs) and Engelhardia roxburghiana (Enr). The sum of SS and starch is considered as the NSCs. Samples denoted Initial were collected in March 2014, and samples denoted Control and Defoliation were collected in January 2015. The mean ± SE are presented (n = 3–6), and different letters indicate significant differences in NSCs in different tissues at P = 0.05.

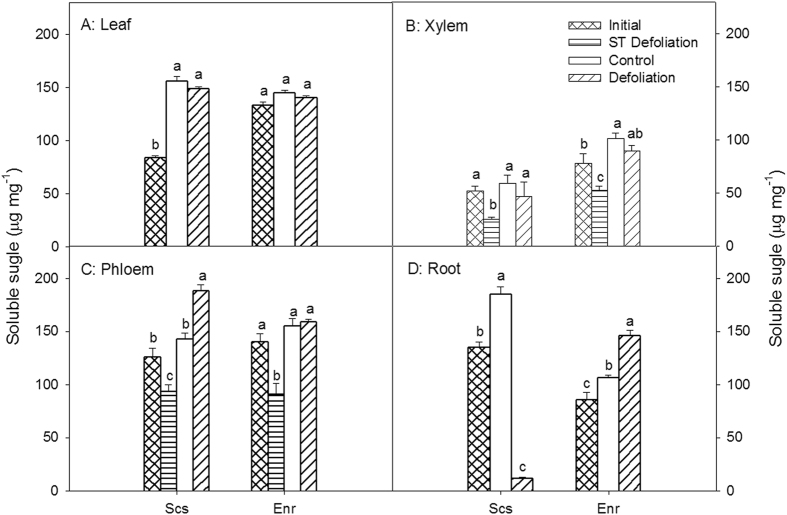

In the samples tested, the NSCs consisted mainly of soluble sugars (SSs) except in E. roxburghiana roots, where starch (St; data not presented) accounted for a slightly greater portion of the NSCs than did SS (Figs 3 and 4). The SS concentrations in the S. superba leaves and roots sampled in March 2014 were all significantly lower than those of the control samples collected in January 2015 (p < 0.01), while no significant differences in the xylem and phloem SS concentrations of the samples collected at the different times were observed (p > 0.37). There were no significant differences in SS concentrations among E. roxburghiana organs and tissues collected between March 2014 and January 2015 (p > 0.85). In both species, the SSs in all defoliated tissues except for the S. superba roots were not lower than those of the corresponding tissues in the controls.

Figure 4.

Soluble sugar (SS) concentrations in leaves, xylem, phloem, and roots of Schima superba (Scs) and Engelhardia roxburghiana (Enr). Samples denoted Initial were collected in March 2014, ST Defoliation samples were collected in April 2014, 20 days after defoliation, and samples denoted Control and Defoliation were collected in January 2015. The mean ± SE is presented (n = 3–6), and different letters indicate significant differences in SS in different tissues at P = 0.05.

The NSCs and SSs of defoliated shoots sampled in April, just 20 days after defoliation, were also measured. Consistently, the SS and NSC concentrations in the xylem and phloem of the defoliated shoots sampled in April in both species were all significantly lower than those measured at any other time. The NSC concentrations in the xylem and phloem and the SS concentration in the xylem of S. superba were lower than those in the corresponding tissues of E. roxburghiana, suggesting that defoliated S. superba that had just finished renewing leaves immediately mobilized the remaining NSCs over the short term for resprouting, resulting in the lower NSC reserve in S. superba.

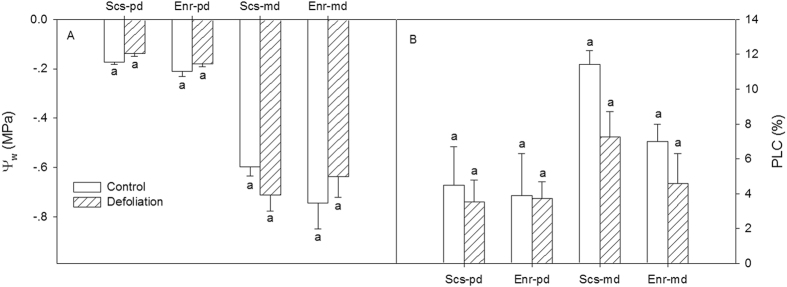

Impact of defoliation on hydraulic status

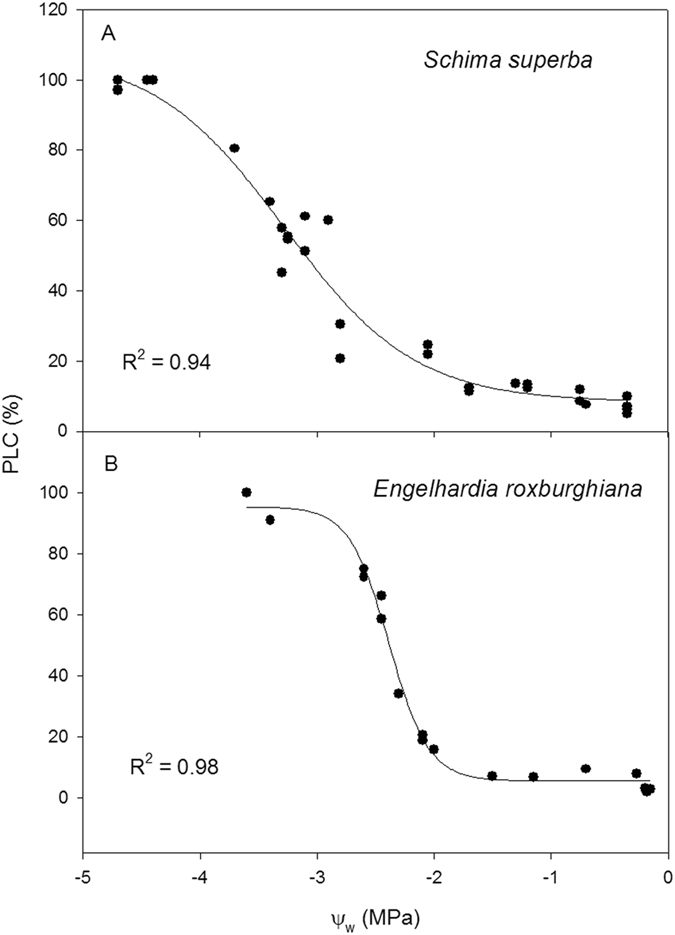

Defoliation had no significant effect on predawn water potential, midday water potential, predawn PLC or midday PLC in either species (Fig. 5). For both the control and the defoliation treatment, the predawn potentials of the two species were high, at approximately −0.1~−0.2 MPa, and their midday water potentials were not lower than −0.8 MPa. The predawn and midday PLC values were relatively small, which indicates that the hydraulic status of the two species was normal and that hydraulic failure did not occur under the local weather conditions. P50 is the water potential at which 50% of the hydraulic conductivity is lost, and it is an indicator of the resistance of xylem to air embolism. The P50 of E. roxburghiana was −2.2 MPa, while that of S. superba was −2.8 MPa (Fig. 6); these values, together with the xylem vulnerability curves (VC), showed that the former was more susceptible to cavitation than the latter.

Figure 5.

(A) Predawn (pd) and midday (md) water potential, and (B) predawn and midday PLC (percentage loss of hydraulic conductivity) for the control and defoliation treatment for Schima superba (Scs) and Engelhardia roxburghiana (Enr). The mean ± SE is presented (n = 3–6), and different letters indicate significant differences in the values at P = 0.05.

Figure 6.

Xylem vulnerability curves to cavitation for Schima superba (Scs) and Engelhardia roxburghiana (Enr).

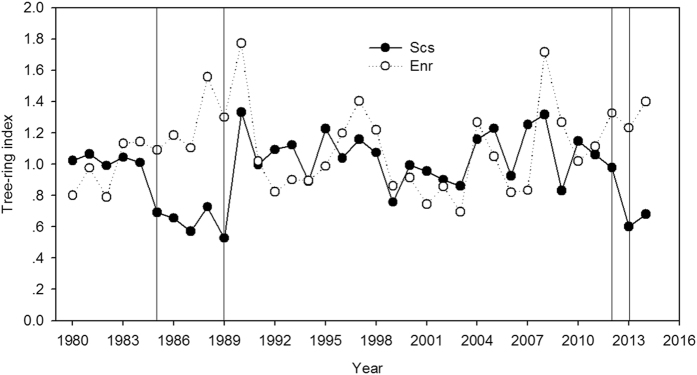

Tree ring analysis of the two species

A retrospective analysis based on ring growth showed that the growth trend of S. superba was lower than that of E. roxburghiana during the insect pest outbreak periods (1985–1989 and 2012–2013), as shown in the tree ring chronologies (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Tree ring indices for Schima superba (Scs) and Engelhardia roxburghiana (Enr) for the period of 1980–2014. The areas between two vertical lines indicate the insect outbreak periods.

Discussion

The concentrations of NSCs in a tree are indicative of the balance between the carbon being fixed and that being utilized for growth and metabolism or exuded below ground18. Carbon reserves fluctuate along with plant phenological events17, 18. The impacts of the loss of carbon reserves in the leaves on trees depend upon the time of year in which the leaves are lost28–30. In the studied region, all of the insect outbreaks occurred in March–April, just after S. superba renews its leaves (February). In contrast, E. roxburghiana renews its leaves in May, after the insect outbreaks26. The observed data in this study showed that the S. superba NSC concentrations in March (when S. superba had just produced new leaves) were significantly lower than those found in January (before annual leaf renewal, which was considered as the control). These observations suggest that the leaf renewal process consumed much of the NSC reserves in all of the tissues tested. However, there were no significant differences in NSC concentrations for any of the E. roxburghiana tissues sampled from control (non-defoliated) trees between March 2014 and January 2015. As stated above, the annual leaf renewal of E. roxburghiana occurs in May; therefore, the NSC concentrations in the samples collected in March 2014 and in January 2015 might not be affected by leaf renewal. The results in this study exhibited that carbon reserves in the two species fluctuated along with their respective phenological events. In artificial defoliation imitating an insect pest attack during March, the leaves that were newly produced were removed for S. superba, but the leaves that were almost one-year-old were removed for E. roxburghiana. As a result, during canopy rebuilding, the NSC concentrations decreased in S. superba, and the subsequent defoliation severely prevented NSC restoration in the roots and the stem xylem. In contrast, NSCs were restored in E. roxburghiana to much closer to the control levels, even in roots.

The storage of nonstructural carbon is of vital importance to woody plants because the NSC reserves enable long-lived organisms to tolerate biotic and abiotic stress, including pests, physical disturbances and drought31, 32. The carbon starvation hypothesis indicates that the balance between plant carbon uptake and expense is upset during long-term external stress, resulting in reduced growth and even death3, 21, 33, 34. In this study, artificial defoliation simulating insect pest attack was conducted in March 2014. In January 2015, following an entire growing season, growth rates and physiological parameters, including NSC concentration, were measured. With the NSC reserves of S. superba already reduced by leaf renewal, the subsequent defoliation significantly decreased the NSC concentrations in the roots and xylem even further—especially in the roots, where the NSC concentration was reduced to 6.6% of the control level. In contrast, the NSC concentration of the defoliated E. roxburghiana remained at 77.2% of the control level.

Long-term or severe suppression of carbon fixation can lead to a significant reduction in root carbon reserves35. It has been indicated that the carbohydrate reserves in the roots of defoliated trees remained low for up to two growing seasons, which is consistent with the fact that we found that the root NSC concentrations were still low even 10 months after defoliation, particularly in the case of S. superba. The carbon reserves of tree roots play a critical role in survival and the restoration of growth rates after defoliation19, 20, 36. The low survival rates of S. superba post-defoliation may be ascribed to its extremely low root NSC reserves. The sink hierarchy hypothesis proposes that the re-establishment of root NSC reserves after defoliation is hindered by the fact that the root system is at the end of the carbon transport chain and therefore has a lower priority for carbohydrate allocation despite the fact that it is a large carbon sink37. There were significant differences between the two tree species in terms of post-defoliation root NSC concentrations. This fact may account for the different responses of the two host species to the insect pest attacks in recent years.

It is well known that defoliation significantly lowers the rates of tree growth, including growth in woody tissues38, 39 and branch size36. In this study, leaf size and new shoot length in both S. superba and E. roxburghiana decreased in response to defoliation. Such changes have also been reported in previous studies22, 38. Taking interactions with the phenology cycle into consideration, defoliation impeded the growth of S. superba more than that of E. roxburghiana. The Huber value of S. superba shown in Fig. 1 significantly increased, suggesting a decrease in the total leaf area (Supplemental Fig. 2). Because leaves constitute the photosynthetic apparatus, they directly determine post-defoliation carbon recovery40. The increased SLA of defoliated S. superba (relative to the control) indicated that the amount of dry matter per leaf area decreased, which is commonly observed after defoliation38. The net photosynthetic rates per unit area in both species subjected to defoliation were restored to the corresponding control levels. The total assimilation capacity would therefore be mainly determined by the total leaf area (Supplemental Fig. 2). The lower total leaf area in defoliated S. superba may have limited its restoration of NSC and its growth. The reductions in the radial growth of mature S. superba trees during the pest outbreaks and the subsequent years also provided evidence that both assimilation and growth rates were reduced in infested S. superba trees.

The NSC concentrations of the aerial parts, including the E. roxburghiana leaves, xylem and phloem and the S. superba phloem, were restored to control levels within ten months after defoliation, while the root NSC reserves were not. These findings lend credence to the statement that new photosynthate is distributed preferentially to the shoots and leaves rather than the roots30, 36, 41, 42. This distribution pattern of new photosynthate favours the growth of the photosynthesis apparatus required for carbon fixation. Unlike in E. roxburghiana, the NSC concentration in the xylem of defoliated S. superba was not restored to the control level. This observation provided additional evidence that E. roxburghiana restored its NSC reserves more effectively than did S. superba.

The NSC concentrations of the aerial tissues were restored to levels of or close to those of the control. However, the total leaf area and the current-year shoot length were significantly lower than those of the control, especially for S. superba. This discrepancy suggests that NSC restoration was more successful in the recovery process than was growth re-establishment. This finding aligns with those reported in previous studies38, 43, 44. To improve their chances of survival when facing external stressors, trees may inhibit their growth activity21, 45. Alternatively, direct constraints on growth (sink limitation) could also lead to increased NSC availability for storage9, 46. The relatively fast recovery of NSC reserves in the absence of growth may also be related to greater NSC availability in the absence of the strong sink strength of growing buds46. Additionally, the reduced growth with a decrease in leaf area may not necessarily be due to carbon limitation but to other factors, such as hormonal control after a reduction in the sink limitation from leaves.

Regardless of the treatment, the predawn water potentials for both S. superba and E. roxburghiana were relatively high (−0.13~−0.2 MPa). The midday water potentials were not lower than −0.8 MPa. The mean midday PLC did not exceed 12%. The maximum PLC was less than 20%. Our results were similar to those reported in a recent study conducted in the same geographic region as ours, in which a mean predawn water potential of −0.31 MPa was found for forty-eight indigenous tree species during the mid-dry season47. This finding indicates that the potential risk of hydraulic failure due to seasonal drought was low. Furthermore, the P50 of S. superba was −2.8 MPa, while the P50 of E. roxburghiana was −2.2 MPa, indicating that the xylem resistance to cavitation of S. superba was higher than that of E. roxburghiana. The aforementioned results and information may not support the hypothesis that the combination of seasonal drought and carbon starvation was more detrimental to S. superba than to E. roxburghiana. The seasonal drought in the experimental region was relatively mild by then and might not contribute to reduced growth and increased mortality after defoliation. In addition, the young trees all grew in the understory, and the transpiration demand was likely low. Thus, the morphological and physiological differences between the two species after defoliation may be due mainly to the different degrees of carbon deficit.

The annual and seasonal temperatures in both the dry and wet seasons in the Dinghu Mountains region have significantly increased since 1954. In addition, the annual number of rain-free days has significantly increased since 198025. The information reported above suggests that climate change trends seem to promote T. quadraria outbreaks, and in general, the emergence of T. quadraria tends to occur in warm humid regions, such as the Dinghu Mountains23. With global climate change and the differential responses of the two species to T. quadraria attacks, S. superba is expected to decline in the forest over the longer term. No such insect outbreaks are known to occur at higher elevations or in colder regions.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that during the canopy rebuilding phase of the tree phenology cycle, the NSC concentrations decreased in Schima superba leaf, stem xylem, stem phloem and root tissues. Artificial defoliation that simulated an insect pest attack severely inhibited both leaf and shoot growth and prevented the restoration of NSCs in the storage tissues of S. superba roots and xylem after ten months. These effects led to high tree mortality rates. A retrospective analysis based on ring growth rates in mature trees showed that outbreaks of the insect T. quadraria reduced radial growth in S. superba. In contrast, another canopy species, Engelhardia roxburghiana, has a different phenology cycle from that of S. superba. E. roxburghiana, which renews its leaves (in May) after the insect outbreak (in March-April), suffered far fewer adverse effects of defoliation and insect pest attacks than did S. superba. Although defoliation reduced leaf and shoot growth rates in E. roxburghiana as well, the extent of the reduction was less than that seen in S. superba. The NSCs in the defoliated E. roxburghiana recovered almost to control levels within ten months after defoliation. Tree ring analysis indicated that E. roxburghiana radial growth is not impeded by the insect pest outbreaks. Thus, when their interactions with phenology are taken into account, defoliation and insect pest outbreaks hindered the growth rates, NSC restoration and survival rates of S. superba more than those of E. roxburghiana. The water relation measurements in this study did not demonstrate any interaction between source limitation and water deficit.

Methods

Study site and experimental design

This study was conducted at the Dinghu Mountains Forest Ecosystem Research Station (DFERS; 23°09′21″–23°11′30″N, 112°32′39″–112°35′41″E), Chinese Academy of Sciences, central Guangdong, southern China. The region is characterized by a typical low subtropical monsoon humid climate, with a dry season from October to March. The mean annual total precipitation is approximately 1900 mm, of which nearly 80% occurs during the wet season (April to September). The mean annual temperature is 21.4 °C, with the lowest and highest monthly mean temperatures of 12.6 °C in January and 28.0 °C in July, respectively. The mean relative humidity is 77.7%. The bedrock includes sandstone and shale. The soils are ultisols and udults with a pH of 4.0–4.9. There are three major forest types in this region: pine (early successional stage), mixed pine and broadleaf (mid-successional stage) and evergreen broadleaf (advanced successional stage).

The objective of this study was to understand why the two evergreen broadleaf species in this region, namely, Engelhardia roxburghiana Wall. (Juglandaceae) and Schima superba Gardn. et Champ. (Theaceae), responded differently to insect pest attacks in recent years23. These two trees are canopy species in the DFERS. Insect [T. quadraria (Geometridae of Lepidoptera)] outbreaks occurred periodically in recent years in the DFERS region. The latest occurrences were in March and April of 2012 and 2013. The extent of insect infestation was similar for both E. roxburghiana and S. superba, with defoliation of more than 70% based on a field survey we conducted in late April of 2013 and consultation with the forest ranger in the national reserve. We selected twelve young trees each of S. superba and E. roxburghiana, all similar in size and growing naturally in the Dinghu Mountains. The young trees were all naturally regenerated and grew in the understory of the evergreen broadleaf forest. The average diameter at breast height (DBH) and height of S. superba were 1.84 (±0.57, ±SE) cm and 2.77 (±0.97) m, respectively, and for E. roxburghiana, the average measurements were 1.28 (±0.33) cm and 2.76 (±0.88) m, respectively. Six young trees per species were used as test subjects for simulating insect attacks in terms of leaf chewing, whilst the other six served as controls. We manually removed all of the foliage in March 2014. By January 2015, all six defoliated young E. roxburghiana trees had survived, but three of the young defoliated S. superba trees had died. In January 2015, physiological indices of all surviving defoliated young trees and controls were measured. To understand the consequences of carbon stress, including its interaction with seasonal drought, we planned to take the main measurements in the dry season. Additionally, carbon stress may play a role in longer-term feedbacks and pathways to mortality. For the retrospective analysis based on ring growth measurements, twenty trees per species in the same area with DBH values of approximately 30–50 cm and ages of approximately 50 years were studied.

Growth responses

One sun-exposed twig per tree was collected for growth analyses in January 2015. All of the leaves on each twig were removed and collected for the measurement of the total leaf area with a leaf area meter (Li-3000C; Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). For each twig, the Huber value (Hv) was calculated as the sapwood area divided by the total leaf area of the cut twig. More than six fully expanded leaves per individual were selected for the determination of the average leaf area (LA). The leaves were then heated at 105 °C for 20 min to stop all enzymatic activity and then oven-dried at 75 °C for 48 h to determine the dry leaf mass. The specific leaf area (SLA) was calculated as the leaf area divided by the dry leaf mass. At least three current-year shoots per tree were measured with a ruler in order to obtain the current-year shoot length. The net photosynthetic rate (Pn) was measured with a Li-6400XT portable photosynthesis system (Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) on sunny days in January 2015. The measurements were made between 09:00 h and 11:30 h. Three sun-exposed leaves per tree were selected for the photosynthetic measurements. Measurements were taken using a standard 2 cm × 3 cm chamber equipped with blue-red light emitting diodes (LED) providing a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 1500 µmol m−2 s−1. The ambient CO2 concentration and leaf temperature were maintained at 400 ppm and 18 °C during the experiment, respectively.

Chemical analyses

The leaf, stem and root samples used for the measurement of soluble sugar (SS) and starch (St) were collected in March 2014 (before defoliation) and in January 2015 (ten months after defoliation). The stems were separated into xylem and phloem. All of the tissue samples were heated at 105 °C for 20 min to stop all enzymatic activity and then oven-dried at 75 °C for 48 h. The dried leaves, stem phloem and xylem and fine roots (0.5–5 mm in diameter) were ground and sieved through a 100-mesh screen, and the powder was used for the determination of soluble sugar (SS) and starch (St) content using the anthrone-sulfuric acid method48. The SS was first extracted three times from the ground samples using 80% ethanol at 80 °C. The residue obtained after extraction was analysed for starch content by digestion using perchloric acid solution, and the glucose was detected using colourimetry. Following extraction, the concentrations of SS and St were determined photometrically in the presence of anthrone-sulfuric acid reagent using a 96-well microplate photometer (Model SpectraMax 190; Molecular Devices Co., San Francisco, CA, USA) with anthrone-sulfuric acid reagent. The sum of SS and St is considered as the total nonstructural carbohydrates (NSCs).

Predawn and midday water potential and percentage loss of hydraulic conductivity

Predawn and midday twig water potentials were measured using a portable pressure chamber (Model No. 1000; PMS Instruments Co., Corvallis, OR, USA.) on sunny days in January 2015. The predawn water potential (Ψpd) was measured between 05:00 h and 06:00 h, whilst the midday water potential (Ψmd) was measured between 11:30 h and 13:30 h. Two twigs per tree were selected and immediately measured in situ.

The maximum xylem vessel length for each species was measured before the percentage loss of hydraulic conductivity (PLC) determination in order to avoid the introduction of errors when cutting branches for the PLC measurements. The maximum vessel length was measured by the “injection air method” as described by Cohen et al.49 and Wang et al.50. Long shoots were cut and injected with compressed air (at approximately 0.15 MPa) from the cut end; the other end was immersed in water. Stem segments (1 cm long) were sequentially excised back until bubbling was observed. The length of the remaining stem was identified as the maximum vessel length. The mean maximum vessel lengths for S. superba and E. roxburghiana were 27.9 ± 0.5 cm and 38.3 ± 0.6 cm, respectively. Thus, it was ensured that the shoots collected for the PLC measurements were longer than the maximum vessel length.

Samples for predawn and midday PLC measurements were collected at the same time as those used for the determination of twig water potential. Cutting branches in air readily causes inaccurate PLC values51. To avoid this problem, a plastic funnel was wrapped around the branch, sealed with tape and filled with distilled water. The branch was then cut under water using sharp pruning shears, and the cut base was immediately transferred to a bucket filled with distilled water. The cut ends of successive segments were submerged under water51–53. The leafy end of the branch was then covered with a large black plastic bag. The bucket containing the branches immersed in water was transferred to the laboratory.

The PLC of predawn and midday branches was measured with a low pressure flow meter (LPFM) as described by Sperry et al.54. The LPFM apparatus was cleaned prior to the PLC measurements by filling it with bleach solution, setting it aside for at least 5 h and then rinsing it with tap water. Stem segments approximately 5 cm in length and 4 mm in diameter were excised under water and then mounted onto the LPFM system, which had been prefilled with ultra-pure, degassed 25 mM KCl solution passed through a 0.22-μm filter. The initial hydraulic conductance (Ki) was measured gravimetrically by determining the flow rate of potassium chloride (KCl) solution at a pressure differential of 4 kPa. The stem segment was then flushed at a pressure of 1.75 MPa for 1 min in order to remove air embolisms. The hydraulic conductivity was then determined once again at a pressure differential of 4 kPa and set as the maximum hydraulic conductivity (Kmax). The PLC was calculated as follows:

| 1 |

Xylem vulnerability curves

Xylem vulnerability curves (VC) were constructed by plotting stem PLC against corresponding xylem tension values obtained via bench dehydration52, 54. The branches used in this assay were similar to those used in the predawn PLC measurements except they were longer, forked and collected from naturally growing trees. The branches were removed from the water and dehydrated on the laboratory bench at ambient irradiance and temperature in order to obtain a series of xylem tensions over a range of PLC values. The branches were carefully wrapped in aluminium foil once they reached the desired tension. After one hour of equilibration, a short leafy shoot was cut in air from one fork of each branch at least one maximum vessel length distant from the sample segment used for PLC measurement. The purpose of this procedure was to determine the xylem tension within the pressure chamber. Soon after excising the short shoot, two to four segments used for PLC determination were cut under water and then measured as described above. To acquire enough data to construct complete VC, more than 30 branches were measured for each species. The VCs were fitted using the equation below55:

| 2 |

Ring width measurement

Trees were sampled in the area where frequent insect pest outbreaks have occurred in recent years. One core from the south side of each tree was extracted at breast height using 5-mm diameter increment borers. In total, 20 cores were collected for each species. The samples were taken to the laboratory, dried, mounted and sanded. Tree ring widths were measured to the nearest 0.01 mm using a LINTAB system (Model No. 6; Rinntech Instruments Co., Heidelberg, Germany). The cross-dating control was evaluated using the COFECHA program56. The chronologies were constructed using the ARSTAN program57. Age- and growth-related trends in tree ring series were fitted to a negative exponential curve.

Data analysis

The data were log transformed to meet the assumptions of homogeneity of variance and normality when necessary. We examined the effect of defoliation on carbohydrate reserves in each tissue via repeated-measures ANOVA (over time; control versus defoliation). The other data were analysed using two-way ANOVA (species and treatments) followed by Student’s t multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using SAS v10 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All statistically significant differences were tested at α = 0.05. Only three defoliated young S. superba trees were surviving in January 2015; therefore, only three replicates were available for this particular treatment. All other species and treatments had six replicates.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31290223, 31270648) and the basic research foundation from the Institute of New Forestry Technology, Chinese Academy of Forestry (CAFYBB2017SY047).

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the study: X.W., S.L. and Z.C. Performed the experiments: Z.C., L.W. and Y.D. Analysed the data: Z.C. Wrote the manuscript: Z.C. and X.W. All authors contributed to the revisions.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09757-2

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Allen C, et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Forest Ecol Manag. 2010;259:660–684. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartmann H, Adams HD, Anderegg WR, Jansen S, Zeppel MJ. Research frontiers in drought-induced tree mortality: crossing scales and disciplines. New Phytol. 2015;205:965–969. doi: 10.1111/nph.13246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDowell N, et al. Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought? New Phytol. 2008;178:719–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marquis RJ, Newell EA, Villegas AC. Non-structural carbohydrate accumulation and use in an understory rain-forest shrub and relevance for the impact of leaf herbivory. Funct Ecol. 1997;11:636–643. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2435.1997.00139.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudgeons J, et al. Defoliation by introduced Diorhabda elongata leaf beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) reduces carbohydrate reserves and regrowth of Tamarix (Tamaricaceae) Biol Control. 2007;43:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2007.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quentin AG, Beadle CL, O’Grady. AP, Pinkard EA. Effects of partial defoliation on closed canopy Eucalyptus globulus Labilladiere: growth, biomass allocation and carbohydrates. Forest Ecol Manag. 2011;261:695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2010.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li MH, Hoch G, Körner C. Source/sink removal affects mobile carbohydrates in Pinus cembra at the Swiss treeline. Trees- Struct Funct. 2002;16:331–337. doi: 10.1007/s00468-002-0172-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palacio S, Hester AJ, Maestro M, Millard P. Browsed Betula pubescens trees are not carbon-limited. Funct Ecol. 2008;22:808–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01433.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palacio S, Hernández R, Maestro-Martínez M, Camarero JJ. Fast replenishment of initial carbon stores after defoliation by the pine processionary moth and its relationship to the re-growth ability of trees. Trees- Struct Funct. 2012;26:1627–1640. doi: 10.1007/s00468-012-0739-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muzika RM, Liebhold AM. Changes in radial increment of host and nonhost tree species with gypsy moth defoliation. Can J Forest Res. 1999;29:1365–1373. doi: 10.1139/x99-098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tikkanen OP, Julkunen-Tiitto R. Phenological variation as protection against defoliating insects: the case of Quercus robur and Operophtera brumata. Oecologia. 2003;136:244–251. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Z, Kolb TE, Clancy KM. Mechanisms of Douglas-fir resistance to western spruce budworm defoliation: bud burst phenology, photosynthetic compensation and growth rate. Tree Physiol. 2001;21:1159–1169. doi: 10.1093/treephys/21.16.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kursar TA, Coley PD. Nitrogen content and expansion rate of young leaves of rain forest species: implications for herbivory. Biotropica. 1991;23:141–150. doi: 10.2307/2388299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coley PD, Barone JA. Herbivory and plant defenses in tropical forests. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1996;27:305–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanover JW. Physiology of tree resistance to insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 1975;20:75–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.20.010175.000451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMillin JD, Wagner MR. Season and intensity of water stress effects on needle toughness of ponderosa pine. Can J Forest Res. 1996;26:1166–1173. doi: 10.1139/x26-130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newell EA, Mulkey SS, Wright SJ. Seasonal patterns of carbohydrate storage in four tropical tree species. Oecologia. 2002;131:333–342. doi: 10.1007/s00442-002-0888-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodruff DR, Meinzer FC. Water stress, shoot growth and storage of non-structural carbohydrates along a tree height gradient in a tall conifer. Plant Cell Environ. 2011;34:1920–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landhäusser SM, Lieffers VJ. Leaf area renewal, root retention and carbohydrate reserves in a clonal tree species following aboveground disturbance. J Ecol. 2002;90:658–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.00699.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeppel MJB. Drought and resprouting plants. New Phytol. 2015;206:583–589. doi: 10.1111/nph.13205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDowell NG. Mechanisms linking drought, hydraulics, carbon metabolism, and vegetation mortality. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:1051–1059. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.170704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderegg WR, Callaway ES. Infestation and hydraulic consequences of induced carbon starvation. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:1866–1874. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.198424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Z, et al. The interactions of population dynamics of Thalassodes quadraria and the plant community structure and climate factors in Dinghushan. Chinese J Ecol. 2000;19:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang C, et al. Dynamics and causes of woody plant death in the monsoon evergreen broad-leaved forest in Dinghushan Nature Reserve. Acta Ecologica Sinica. 2006;26:2457–2462. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou G, et al. Quantifying the hydrological responses to climate change in an intact forested small watershed in Southern China. Glob Change Biol. 2011;17:3736–3746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02499.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li MJ, Wang ZH. The phenology of common plants in Ding Hu Shan. Tropical and subtropical forest ecosystem. 1984;2:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schweingruber, F. H. Tree Rings and Environment: Dendroecology (Paul, 1996).

- 28.McLaughlin SB, McConathy RK, Barnes RL, Edwards NT. Seasonal changes in energy allocation by white oak (Quercus alba) Can J Forest Res. 1980;10:379–388. doi: 10.1139/x80-063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webb WL, Kilpatrick KJ. Starch content in Douglas-fir: diurnal and seasonal dynamics. Forest Sci. 1993;39:359–367. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanderklein DW, Reich PB. The effect of defoliation intensity and history on photosynthesis, growth and carbon reserves of two conifers with contrasting leaf lifespans and growth habits. New Phytol. 1999;144:121–132. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1999.00496.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Körner C. Carbon limitation in trees. J Ecol. 2003;91:4–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00742.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dietze M, et al. Nonstructural carbon in woody plants. Ann Rev Plant Physio. 2014;65:667–687. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker J, Patton RL. Effects of drought and defoliation on some metabolites in roots of black oak seedlings. Can J Forest Res. 1975;5:457–463. doi: 10.1139/x75-063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bossel H. Dynamics of forest dieback: systems analysis and simulation. Ecol Model. 1986;34:259–288. doi: 10.1016/0304-3800(86)90008-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landhäusser SM, Lieffers VJ. Defoliation increases risk of carbon starvation in root systems of mature aspen. Trees-Struct Funct. 2012;26:653–661. doi: 10.1007/s00468-011-0633-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eyles A, Pinkard EA. & Mohammed, C. Shifts in biomass and resource allocation patterns following defoliation in Eucalyptus globulus growing with varying water and nutrient supplies. Tree Physiol. 2009;29:753–764. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wardlaw IF. The control of carbon partitioning in plants. New Phytol. 1990;116:341–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1990.tb00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiley E, Huepenbecker S, Casper BB, Helliker BR. The effects of defoliation on carbon allocation: can carbon limitation reduce growth in favour of storage? Tree Physiol. 2013;33:1216–1228. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpt093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millard P, Hester A, Wendler R, Baillie G. Interspecific defoliation responses of trees depend on sites of winter nitrogen storage. Funct Ecol. 2001;15:535–543. doi: 10.1046/j.0269-8463.2001.00541.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galiano L, Martınez-Vilalta J, Lloret F. Carbon reserves and canopy defoliation determine the recovery of Scots pine 4 yr after a drought episode. New Phytol. 2011;190:750–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson NC, Rowland DL, Corkidi L, Egerton-Warburton L, Allen EB. Nitrogen enrichment alters mycorrhizal allocation at five mesic to semiarid grasslands. Ecology. 2003;84:1895–1908. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[1895:NEAMAA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Markkola A, et al. Defoliation increases carbon limitation in ectomycorrhizal symbiosis of Betula pubescens. Oecologia. 2004;140:234–240. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith A, Stitt M. Coordination of carbon supply and plant growth. Plant Cell Environ. 2007;30:1126–1149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacquet JS, Bosc A, O’Grady A, Jactel H. Combined effects of defoliation and water stress on pine growth and non-structural carbohydrates. Tree Physiol. 2014;34:367–376. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpu018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Brien MJ, Burslem D, Caduff A, Tay J, Hector A. Contrasting nonstructural carbohydrate dynamics of tropical tree seedlings under water deficit and variability. New Phytol. 2015;205:1083–1094. doi: 10.1111/nph.13134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palacio S, Hoch G, Sala A, Körner C, Millard P. Does carbon storage limit tree growth? New Phytol. 2014;201:1096–1100. doi: 10.1111/nph.12602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li R, et al. Are functional traits a good predictor of global change impacts on tree species abundance dynamics in a subtropical forest? Ecol Lett. 2015;18:1163–1173. doi: 10.1111/ele.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanson J, Moller. I. Percolation of starch and soluble carbohydrates from plant tissue for quantitative determination with anthrone. Anal Biochem. 1975;68:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90682-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen S, Bennink J, Tyree MT. Air method measurements of apple vessel length distributions with improved apparatus and theory. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:1889–1897. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang R, Zhang L, Zhang S, Cai J, Tyree MT. Water relations of Robinia pseudoacacia L.: do vessels cavitate and refill diurnally or are R-shaped curves invalid in Robinia? Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37:2667–2678. doi: 10.1111/pce.12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wheeler JK, Huggett BA, Tofte AN, Rockwell FE, Holbrook NM. Cutting xylem under tension or supersaturated with gas can generate PLC and the appearance of rapid recovery from embolism. Plant Cell Environ. 2013;36:1938–1949. doi: 10.1111/pce.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cochard H, et al. Methods for measuring plant vulnerability to cavitation: a critical review. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:4779–4791. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres-Ruiz J, et al. Direct X-Ray microtomography observation confirms the induction of embolism upon xylem cutting under tension. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:40–43. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.249706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sperry JS, Donnelly JR, Tyree MT. A method for measuring hydraulic conductivity and embolism in xylem. Plant Cell Environ. 1988;11:35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1988.tb01774.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pammenter NW, Willigen C. A mathematical and statistical analysis of the curves illustrating vulnerability of xylem to cavitation. Tree Physiol. 1998;18:589–593. doi: 10.1093/treephys/18.8-9.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holmes R. Computer-assisted quality control in tree-ring dating and measurement. Tree-Ring Bull. 1983;43:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cook, E. R. & Kairiukstis, L. A. Methods of Dendrochronology (1990).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.