Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a heterogeneous endocrine disorder that affects reproductive-age women. The mechanisms underlying the endocrine heterogeneity and neuroendocrinology of polycystic ovary syndrome are still unclear. In this study, we investigated the expression of the kisspeptin system and gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse regulators in the hypothalamus as well as factors related to luteinizing hormone secretion in the pituitary of polycystic ovary syndrome rat models induced by testosterone or estradiol.

METHODS:

A single injection of testosterone propionate (1.25 mg) (n=10) or estradiol benzoate (0.5 mg) (n=10) was administered to female rats at 2 days of age to induce experimental polycystic ovary syndrome. Controls were injected with a vehicle (n=10). Animals were euthanized at 90-94 days of age, and the hypothalamus and pituitary gland were used for gene expression analysis.

RESULTS:

Rats exposed to testosterone exhibited increased transcriptional expression of the androgen receptor and estrogen receptor-β and reduced expression of kisspeptin in the hypothalamus. However, rats exposed to estradiol did not show any significant changes in hormone levels relative to controls but exhibited hypothalamic downregulation of kisspeptin, tachykinin 3 and estrogen receptor-α genes and upregulation of the gene that encodes the kisspeptin receptor.

CONCLUSIONS:

Testosterone- and estradiol-exposed rats with different endocrine phenotypes showed differential transcriptional expression of members of the kisspeptin system and sex steroid receptors in the hypothalamus. These differences might account for the different endocrine phenotypes found in testosterone- and estradiol-induced polycystic ovary syndrome rats.

Keywords: Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Hypothalamus, Animal Models, Kisspeptin, Testosterone

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a highly prevalent heterogeneous condition mainly characterized by hyperandrogenism, chronic anovulation and polycystic ovaries 1. Another abnormality that is common in women with PCOS is aberrant gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion, which favors higher production of luteinizing hormone (LH) and an increase in androgen production by the ovaries 2. However, the precise mechanisms underlying LH hypersecretion in PCOS are not well known.

The kisspeptin system, which includes kisspeptin, dynorphin A and neurokinin B/tachykinin 3, is essential for GnRH/LH pulse control, and it is believed that impairments in this system might contribute to endocrine dysfunction in PCOS 3. Furthermore, evidence suggests that neuroendocrine dysfunction in insulin signaling alters GnRH/LH secretion and impair reproductive cyclicity 4.

Exposure to either estrogen or androgens in neonatal life can induce chronic anovulation and polycystic ovaries resembling human PCOS during rat adulthood 5. However, different exposures may result in various endocrine phenotypes 5. For instance, animals exposed to androgens during the neonatal period present increased levels of LH and testosterone. This phenotype is not observed in the estrogen model 6. The aim of this study was to investigate transcriptional changes in the kisspeptin system and GnRH pulse regulators in the hypothalamus as well as factors related to LH secretion in the pituitary in PCOS rat models induced by testosterone or estradiol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

The experimental procedures were described previously 6. In brief, thirty female Wistar rats at 2 days of age were allocated into the following groups for the induction of experimental PCOS: subcutaneous injection of 1.25 mg of testosterone (TG; n=10) 7 or 0.5 mg of estradiol (EG; n=10) 8. Control animals received a single injection of olive oil (vehicle) (CG; n=10). At 90-94 days of age, under anesthesia, blood was obtained from the abdominal aortic artery, animals were decapitated, and the hypothalamus and pituitary gland were removed and stored in RNAlater solution (Ambion; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for 24 h and frozen until use. The measurement of serum levels of LH, FSH and testosterone is described in our previous study 6. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo under protocol number 151/10.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and qRT-PCR conditions were performed as described elsewhere 9. Taqman® assays manufactured by Life Technologies were selected to analyze the gene expression of Gnrh, Gnrhr, Kiss1, Kiss1r, Tac3, Tacr3, Esr1, Esr2, Ar, Cyp19a1, Pdyn and Oprk1 in the hypothalamus and Gnrhr, Kiss1, Kiss1r, Insr and Ar in the pituitary (Table 1). The data were analyzed using Sequence Detection Software (version 2.0.6), and Ct values were transformed to quantities using the comparative Ct method (ΔΔCt).

Table 1.

Description of the probes and primers used in the study.

| Gene symbol | Gene name | TaqMan ID | RefSeq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference genes | |||

| Actb | Actin, Beta | 4352340E | NM_031144.3 |

| Gapdh | Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase | 4352338E | NM_017008.4 |

| Ppia | Peptidylprolyl Isomerase A (Cyclophilin A) | Rn00690933_m1 | NM_017101.1 |

| Target genes | |||

| Gnrh1 | Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone 1 | Rn00562754_m1 | NM_012767.2 |

| Gnrhr | Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor | Rn00578981_m1 | NM_031038.3 |

| Kiss1 | Kisspeptin | Rn00710914_m1 | NM_181692.1 |

| Kiss1r | KISS1 Receptor | Rn00576940_m1 | NM_023992.2 and NM_001301151.1 |

| Tac3 | Tachykinin 3 | Rn00569758_m1 | NM_019162.2 |

| Tacr3 | Tachykinin Receptor 3 | Rn00566955_m1 | NM_017053.1 |

| Pdyn | Prodynorphin | Rn00571351_m1 | NM_019374.3 |

| Oprk1 | Opioid Receptor, Kappa 1 | Rn01448892_m1 | NM_017167.2 |

| Esr1 | Estrogen Receptor 1 (ER Alpha) | Rn01640372_m1 | NM_012689.1 |

| Esr2 | Estrogen Receptor 2 (ER Beta) | Rn00562610_m1 | NM_012754.1 |

| Ar | Androgen Receptor | Rn00560747_m1 | NM_012502.1 |

| Insr | Insulin Receptor | Rn00690703_m1 | NM_017071.2 |

| Cyp19a1 | Cytochrome P450, Family 19, Subfamily A, Polypeptide 1 | Rn00567222_m1 | NM_017085.2 |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (version 6.05; GraphPad Software, USA). ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test was performed to analyze data with a normal distribution. For skewed data, the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was performed. A value of p<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. F-ratios (F) are described for significant differences. The degrees of freedom was equal to 29 for all analyses.

RESULTS

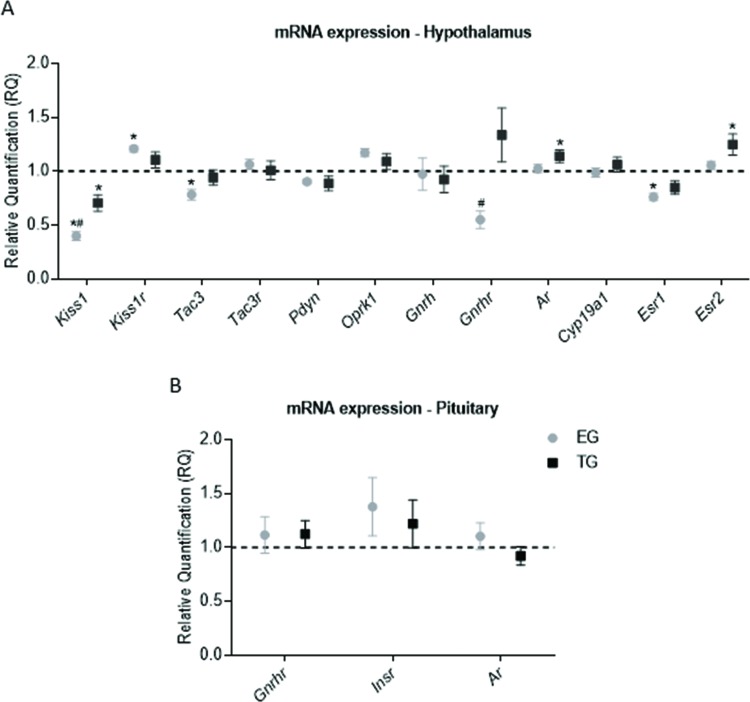

Treated rats had closed vaginas, and all rats in the CG had normal estrous cycles. In the hypothalamus, kisspeptin (Kiss1), neurokinin B (Tac3), and estrogen receptor (ER)-α (Esr1) were downregulated in the EG relative to the CG (p=0.0001, F=35.92; p=0.01, F=5.193; and p=0.0015, F=8.342, respectively). The expression levels of Kiss1 and GnRH receptor (Gnrhr) were lower in the EG than in the TG (Kiss1: p=0.01, F=35.92; Gnrhr: p=0.01, F=6.748), and the expression of the gene encoding the KISS1 receptor (Kiss1r) was higher in the EG than in the CG (p=0.007, F=5.142). Kiss1 was also expressed at a lower level in the TG than in the CG (p=0.001, F=35.92). TG rats exhibited upregulation of the androgen receptor (Ar) and ER-β (Esr2) genes compared to CG animals (p=0.04, F=3.522; and P=0.02, F=4.497, respectively). The expression of Gnrh, Oprk1, Pdyn, Tacr3 and Cyp19a1 did not differ significantly among the groups (Figure 1A). No significant difference was observed in pituitary gene expression (Figure 1B), and Kiss1 and Kiss1r mRNA levels were undetectable.

Figure 1.

Transcriptional expression in the hypothalamus and pituitary. The data are shown as the means ± SEM. ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test was performed for data with a normal distribution, and the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was performed for skewed data. (A) mRNA expression in the hypothalamus. (B) mRNA expression in the pituitary. * - vs the CG (p<0.05), # - EG vs TG (p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

Our group showed in a previous study that testosterone or estradiol exposure in neonatal life leads to different PCOS-like phenotypes in adult female rats. Testosterone-induced PCOS rat models exhibit increased LH and testosterone levels, anovulation, and polycystic ovaries, while estradiol-induced PCOS rat models exhibit anovulation and polycystic ovaries but no alterations in the serum levels of gonadotropins or testosterone 6. In the current study, we aimed to further understand the heterogeneity of PCOS endocrine phenotypes by studying the hypothalamic neuroendocrine transcriptional profile of the kisspeptin system and GnRH pulse regulators as well as factors related to LH secretion in the pituitary of these two PCOS rat models.

It has been hypothesized that androgenized rat models have increased GnRH expression 10, and this event, in part, seems to be mediated by the interaction of androgens with androgen receptors (ARs) in the hypothalamus 11. Feng et al. 10 have shown that the AR is co-expressed in GnRH-neurons of adult female rats. In rats exposed to androgens in this study, an upregulation of Ar occurred in the hypothalamus. In vitro, AR activation has been shown to increase GnRH-neuron firing activity and GnRH secretion 12, 13.

Kisspeptin is an important factor involved in the stimulation of GnRH/LH secretion as well as the GnRH/LH surge that induces ovulation 3. Androgen and estrogen exposure downregulate kisspeptin gene expression, with this effect being more pronounced in estrogen-exposed rats. The downregulation of kisspeptin might be related to anovulation, because those animals seem to be unable to generate the GnRH/LH surge 6. In contrast, the KISS1 receptor gene was upregulated in rats exposed to estrogen, which is possibly a compensatory mechanism for low levels of kisspeptin.

Despite downregulation of the kisspeptin gene, androgen-exposed rats presented increased levels of LH. However, GnRH pulsatility, which stimulates gonadotropin secretion in a GnRH pulse-dependent manner, as well as LH secretion, is modulated by many factors 14. Other factors might be involved in LH hypersecretion in androgen-exposed rats.

Another factor that might contribute to anovulation in estrogen-exposed rats is the lower level of ER-α mRNA because female rats treated with an ER-α antagonist could not achieve a GnRH/LH surge, even with induction of the LH surge by intracerebroventricular administration of kisspeptin. However, the central administration of an ER-β antagonist did not impair the GnRH/LH surge in female rats 15. Mice with ER-β knockdown, but not those with ER-α knockdown, can generate positive estrogen-mediated feedback for the LH surge, and the action of a specific ligand of ER-α induces the LH surge 16. ER-α is expressed at a higher level in kisspeptin neurons than in GnRH neurons, while ER-β is the main estrogen receptor in GnRH neurons 17, which suggests that estrogen-exposed rats cannot achieve positive kisspeptin neuron-mediated estrogen feedback for GnRH/LH secretion. Androgen-induced PCOS rats exhibited upregulation of the ER-β gene. The role of ER-β in reproduction is not completely known, but this receptor also interacts with an androgen metabolite called 3β-diol 18. However, the role of this metabolite in the GnRH or kisspeptin system is still unknown.

Neurokinin B is considered an important factor in the modulation of GnRH secretion because loss-of-function mutations in the genes encoding both neurokinin B and its receptor induce hypogonadotropic hypogonadism 19. Furthermore, the central administration of a neurokinin B receptor agonist increases LH secretion in female rats 20. Downregulation of the neurokinin B gene (Tac3) may be related to the state of anovulation in estradiol-exposed rats and the lower levels of LH in the estradiol-exposed rats relative to the androgen-exposed rats. Additionally, testosterone- and estradiol-induced PCOS rat models differ regarding GnRH receptor mRNA expression in the hypothalamus, which might contribute to the neuroendocrine differences in those rat models.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the transcriptional expression in neuroendocrine organs in PCOS rat models with different endocrine phenotypes. However, this is a preliminary study, and one limitation is the absence of protein expression analysis.

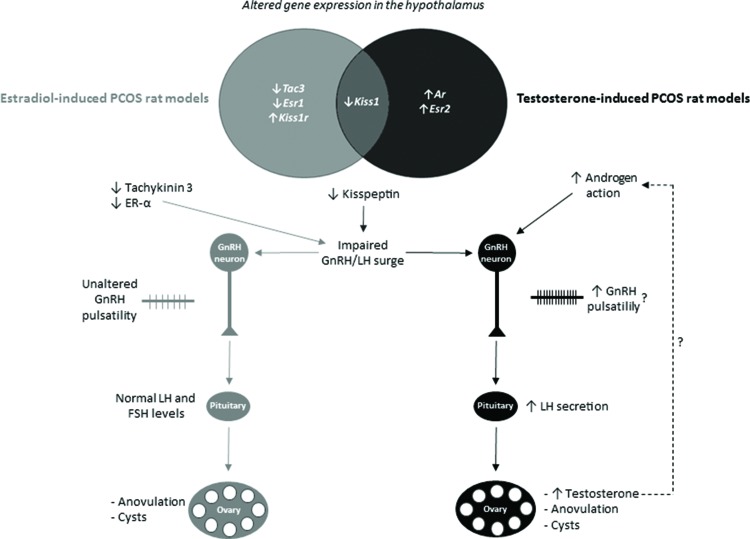

In summary, we found that testosterone- and estradiol-induced PCOS rats with different endocrine phenotypes exhibit differential transcriptional expression of members of the kisspeptin system and sex steroids in the hypothalamus. It is possible that different insults during development activate various neuronal circuitries, which might be related to the heterogeneity of PCOS. The hypothesized effects of altered hypothalamic transcriptional expression on endocrine phenotypes are summarized in Figure 2. These differences seem to be caused by various mechanisms and might account for the different neuroendocrine and endocrine phenotypes found in androgen- and estrogen-induced PCOS rats and women with PCOS.

Figure 2.

Differential transcriptional expression in the hypothalamus and hypothesized effects on the endocrine phenotypes of estradiol- or testosterone-induced PCOS rat models. The diagram shows genes with altered expression in the hypothalamus of estradiol- or testosterone-induced PCOS rat models; these two models only share the downregulation of the kisspeptin gene (Kiss1). Downregulation of the kisspeptin gene might contribute to anovulation in both testosterone- and estradiol-induced PCOS rat models because kisspeptin is essential for the gonadotropin-releasing (GnRH)/luteinizing hormone (LH) surge that precedes ovulation. The testosterone-induced PCOS rat model seems to have increased androgen-mediated stimulation of GnRH neurons, which might increase GnRH pulsatility and increase LH secretion by the pituitary. Increased LH secretion per se stimulates the ovaries to increase testosterone production. In the estradiol-induced PCOS rat model, downregulation of the estrogen receptor-α (ER-α) and tachykinin 3 genes seems to impair the GnRH/LH surge and ovulation. ↓, decreased; ↑, increased.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Maciel GA and Marcondes RR conceived and designed the study. Marcondes RR, Carvalho KC, Giannocco G, Duarte DC and Garcia N performed the experiments. Marcondes RR, Maciel GA, Baracat EC, Maliqueo M, Soares-Junior JM, Silva ID and Carvalho KC analyzed and interpreted the data. Marcondes RR and Maciel GA wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Thiago H. Gonçalves, Luiz F. P. Fuchs, Marinalva de Almeida and Fernanda Condi for their help with animal care and technical support. This research was supported by research grants 2010/17417-3 and 2013/12830-8 from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) - Brazil, and a Master’s degree scholarship given to R.R.M. (134694/2010-4) by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) – Brazil. The funders played no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodarzi MO, Dumesic DA, Chazenbalk G, Azziz R. Polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7((4)):219–31. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dumesic DA, Oberfield SE, Stener-Victorin E, Marshall JC, Laven JS, Legro RS. Scientific Statement on the Diagnostic Criteria, Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Molecular Genetics of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2015;36((5)):487–525. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehman MN, Coolen LM, Goodman RL. Minireview: kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) cells of the arcuate nucleus: a central node in the control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology. 2010;151((8)):3479–89. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiVall SA, Herrera D, Sklar B, Wu S, Wondisford F, Radovick S, et al. Insulin receptor signaling in the GnRH neuron plays a role in the abnormal GnRH pulsatility of obese female mice. PLoS One. 2015;10((3)):e0119995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walters KA, Allan CM, Handelsman DJ. Rodent models for human polycystic ovary syndrome. Biol Reprod. 2012;86((5)):1–12. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.097808. 149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcondes RR, Carvalho KC, Duarte DC, Garcia N, Amaral VC, Simoes MJ, et al. Differences in neonatal exposure to estradiol or testosterone on ovarian function and hormonal levels. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2015;212:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahamed RR, Maganhin CC, Simoes RS, de Jesus Simoes M, Baracat EC, Soares JM., Jr Effects of metformin on the reproductive system of androgenized female rats. Fertil Steril. 2011;95((4)):1507–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.07.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexanderson C, Eriksson E, Stener-Victorin E, Lystig T, Gabrielsson B, Lonn M, et al. Postnatal testosterone exposure results in insulin resistance, enlarged mesenteric adipocytes, and an atherogenic lipid profile in adult female rats: comparisons with estradiol and dihydrotestosterone. Endocrinology. 2007;148((11)):5369–76. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcondes RR, Carvalho KC, Duarte DC, Garcia N, Amaral VC, Simões MJ, et al. Differences in neonatal exposure to estradiol or testosterone on ovarian function and hormonal levels. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2015;212:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng Y, Johansson J, Shao R, Manneras L, Fernandez-Rodriguez J, Billig H, et al. Hypothalamic neuroendocrine functions in rats with dihydrotestosterone-induced polycystic ovary syndrome: effects of low-frequency electro-acupuncture. PLoS One. 2009;4((8)):e6638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foecking EM, Szabo M, Schwartz NB, Levine JE. Neuroendocrine consequences of prenatal androgen exposure in the female rat: absence of luteinizing hormone surges, suppression of progesterone receptor gene expression, and acceleration of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator. Biol Reprod. 2005;72((6)):1475–83. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.039800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun J, Moenter SM. Progesterone treatment inhibits and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) treatment potentiates voltage-gated calcium currents in gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons. Endocrinology. 2010;151((11)):5349–58. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pielecka J, Quaynor SD, Moenter SM. Androgens increase gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron firing activity in females and interfere with progesterone negative feedback. Endocrinology. 2006;147((3)):1474–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbison AE. Control of puberty onset and fertility by gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12((8)):452–66. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roa J, Vigo E, Castellano JM, Gaytan F, Navarro VM, Aguilar E, et al. Opposite roles of estrogen receptor (ER)-alpha and ERbeta in the modulation of luteinizing hormone responses to kisspeptin in the female rat: implications for the generation of the preovulatory surge. Endocrinology. 2008;149((4)):1627–37. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wintermantel TM, Campbell RE, Porteous R, Bock D, Grone HJ, Todman MG, et al. Definition of estrogen receptor pathway critical for estrogen positive feedback to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons and fertility. Neuron. 2006;52((2)):271–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radovick S, Levine JE, Wolfe A. Estrogenic regulation of the GnRH neuron. Front Endocrinol. 2012;3:52. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiroi R, Lacagnina AF, Hinds LR, Carbone DG, Uht RM, Handa RJ. The androgen metabolite, 5alpha-androstane-3beta,17beta-diol (3beta-diol), activates the oxytocin promoter through an estrogen receptor-beta pathway. Endocrinology. 2013;154((5)):1802–12. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Topaloglu AK, Reimann F, Guclu M, Yalin AS, Kotan LD, Porter KM, et al. TAC3 and TACR3 mutations in familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism reveal a key role for Neurokinin B in the central control of reproduction. Nat Genet. 2009;41((3)):354–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan X, Yuan C, Zhao N, Cui Y, Liu J. Prenatal androgen excess enhances stimulation of the GNRH pulse in pubertal female rats. J Endocrinol. 2014;222((1)):73–85. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]