Abstract

Objective

The management of inpatient hyperglycemia and diabetes requires expertise among many healthcare providers. There is limited evidence about how education for healthcare providers can result in optimization of clinical outcomes. The purpose of this critical review of the literature is to examine methods and outcomes related to educational interventions regarding the management of diabetes and dysglycemia in the hospital setting. This report provides recommendations to advance learning, curricular planning, and clinical practice.

Methods

We conducted a literature search through PubMed Medical for terms related to concepts of glycemic management in the hospital and medical education and training. This search yielded 1,493 articles published between 2003 and 2016.

Results

The selection process resulted in 16 original articles encompassing 1,123 learners from various disciplines. We categorized findings corresponding to learning outcomes and patient care outcomes.

Conclusion

Based on the analysis, we propose the following perspectives, leveraging learning and clinical practice that can advance the care of patients with diabetes and/or dysglycemia in the hospital. These include: (1) application of knowledge related to inpatient glycemic management can be improved with active, situated, and participatory interactions of learners in the workplace; (2) instruction about inpatient glycemic management needs to reach a larger population of learners; (3) management of dysglycemia in the hospital may benefit from the integration of clinical decision support strategies; and (4) education should be adopted as a formal component of hospitals’ quality planning, aiming to integrate clinical practice guidelines and to optimize diabetes care in hospitals.

Keywords: Inpatient Diabetes Providers Education, Inpatient Providers Diabetes Learning, Diabetes Providers Education Recommendations, Healthcare Providers Education Inpatient Diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Inpatient glucose control is an issue of major importance. Current evidence suggests that dysglycemia and diabetes are increasingly prevalent (1) and common in hospitals (2–7), and hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia among hospitalized patients are associated with poor clinical outcomes (6, 8–14). The care of diabetes and hyperglycemia in the hospital setting is commonly assumed by physicians and mid-level practitioners in various medical specialties and at different levels of training. This care demands providers’ expertise to address glucose scenarios of varying complexity (10–12, 15). Leading societies in diabetes care and other clinical organizations place continuing education for healthcare providers as a cornerstone of hospitals’ glycemic control programs to optimize care (10, 12, 16).

There is a paucity of knowledge regarding educational strategies to effectively instruct providers on the subject of hospital diabetes management. Many gaps exist among healthcare providers in domains such as contextual and biomedical knowledge, attitudes, clinical decision making, confidence, and familiarity with existing hospital resources in regards to hospital diabetes care (17–22). Furthermore, the impact of providers’ knowledge on diabetes care is poorly understood. Adding to the knowledge gap, limited responsiveness or “clinical inertia” to various tasks related to hospital diabetes management prevails in practice (23–25). Additionally, providers confront barriers in the systems of practice (26), all of which can hinder adequate approaches to inpatient diabetes care. In this challenging practice environment, relevant questions arise: Are the current educational efforts to prepare providers to address the needs of hospitalized patients with diabetes accomplishing their goals? What kinds of strategies can improve educational programs for diabetes management in the hospital?

The purpose of this critical review of the literature is to examine learning and clinical practice outcomes resulting from educational interventions pertaining to the management of diabetes and dysglycemia in the hospital. We defined learning outcomes as changes in knowledge, practice behaviors, or utilization of resources related to the care of hospitalized patients with diabetes. Clinical outcomes represented improvements in various aspects of diabetes care such as treatment approaches, clinical targets, quality of care, length of hospital stay, and continuity of care, among other factors. This review discusses these outcomes in light of the current clinical guidelines for hospital diabetes management and attempts to provide insights for curricular planning aimed at supporting clinical practice recommendations.

Theoretical Framework: Practice and Learning in the Medical Workplace

The inpatient hospital setting is a rich learning environment. Throughout the health education continuum, learning in the context of clinical practice is vital. This process typically starts in higher education programs, continues within more advance clinical contexts in postgraduate training programs, and is maintained by continuing medical education.

Situated learning defines learning that occurs through apprenticeship. It refers to learning in a context of collaboration with other learners and through dynamic interactions between the learner and their environment. Situated learning encompasses informal learning that occurs through the course of routine work and learning by doing in a context that is relevant to the learner (27–30). Opportunities to apply skills or knowledge in diverse contexts can help learners be better prepared to apply those skills to novel contexts. This is also known as transfer, which is a central goal of education (31). Learners come to workplaces as participants with prior knowledge and skills that may or may not align with the goals of an existing curriculum or with current clinical practice recommendations (30). As healthcare learners acquire more responsibility and transition deeper into the complexities of clinical work, they need to apply skills and evoke knowledge that is aligned with best practices. They also need to participate in peer instruction and to display aptitudes while getting the job done efficiently, optimally and with minimal harm to patients.

Learning about the management of patients with diabetes in the hospital requires participation of learners in a way that resonates with concepts of situated leaning. Therefore, we propose that an optimal approach to teaching and learning about diabetes care in the hospital setting requires active participation of learners, should occur in a learning context that is or that simulates clinical practice, and needs to facilitate a collaborative learning environment.

METHODS

We conducted a literature search in PubMed (32) using a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms related to the following four concepts: (1) glycemic management or control; (2) hospital; (3) physicians, residents, or hospitalists; and (4) education or training programs. Keywords and MeSH terms for each of the four concepts were joined together using the Boolean operator “AND.” The complete search yielded 1,493 citations. We selected titles of articles based on their applicability to the topic in question. We then reviewed the abstracts of these titles screened to determine their possible selection. This selection was based on their applicability and on their focus on educational intervention. We excluded abstracts that were not original studies, duplicated, or that reported quality improvement activities being conducted concurrently with the education programs, or articles in which the outcomes of the educational intervention could not be separated from that of other hospital quality activities. Only original peer-reviewed articles in the English and Spanish languages describing educational interventions or programs related to inpatient glycemic management were considered for full article review. We expanded the search by reviewing the reference section of these articles initially selected to be included on this review. We conducted our last search in PubMed not limited by dates in July 2016. Sixteen articles published between 2003 and 2016 were found to meet the inclusion criteria. We used a literature review rubric for the data extraction from these articles that included the following elements: instructional or pedagogical methods used in the various studies; number, discipline, and level of training of learners participating in the studies; the purpose or objectives driving the educational program; the learning outcomes reported among participants; and the outcomes related to patient care or overlapping learning and patient care outcomes as outlined in Table 1. We utilized PRISMA (33), an evidence-based criteria for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as a guide to strengthen the quality of each section of this review. However, our literature search was limited to PubMed. We consider this work a critical review of the literature, as we are comparing the outcomes of these educational studies with a framework of learning theory. This critical review assesses how these studies exhibit ideal characteristics based on learning theories. Thus, the inclusion of the theoretical framework in the previous section provides the foundation of educational theory that supports some of the conclusions of this review.

Table 1.

Educational Programs Related to Glycemic Management in the Hospital

| Author/Publication year/Country (ref) | Educational Instruction/Methods | Participants (N) | Education Program Purpose | Participant Learning Outcome | Patient Care Outcome & Overlapping Learning and Patient Care Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldwin et al., 2005/USA (34) | -Twice daily endocrine rounds with endocrine faculty for 2 weeks -Provision of written guidelines for participants |

-General Medicine residents (16) | -To educate residents on the management of inpatient hyperglycemia without use of sliding scale insulin | -Increased confidence in managing inpatient hyperglycemia without sliding scale insulin | -80% with HbA1c >7% had their diabetes therapy intensified by discharge -Fewer patients had episodes of severe inpatient hyperglycemia -Higher rate of mild hypoglycemia was observed -Reduction in HbA1c from 10.1 to 8% twelve months after discharge |

| Chehade et al., 2010/USA (35) | -Two-hour symposium for residents, nursing, and allied health professionals -Two-hour interactive session for faculty |

-Internal Medicine house staff (N/A) -General and hospital medicine faculty (N/A) -Nursing staff (54) -Allied health professionals (30) |

- To determine whether focused education for physicians and nurses would result in measurable changes in glycemic control | -Not described | -Reduction in hospital mean daily blood glucose levels -Increased frequency of hypoglycemia |

| Conn et al., 2003/Australia (36) | -Two 1-hour workshop of simulated case scenarios of progressive difficulty presented in a workbook format | -Residents postgraduate year 1 (discipline not identified) (15) | -To offer an education program to improve skills and confidence of junior doctors | -Increase in mean performance score immediate and after 3 months of education related to insulin use -Increase in confidence with simple tasks -Reduced confidence with complex task despite improved performance |

-Not described |

| Cook et al., 2009/USA (37) | -Computer based seven 30-minutes modules - Modules were formatted from previous training of 1-hour conference |

-Family Practice residents (8) -Internal Medicine residents (12) |

-To disseminate an inpatient diabetes curriculum among resident physicians | -Not described -Reported benefit: The majority of participating residents indicated that the modules met their expectations and the information was valuable to their inpatient practice |

-Not described |

| DeSalvo et al., 2012/USA (38) | -Online tutorials on diabetes management - Interactive discussions -Question and answer initiated by learners -Case presentation session with emphasis on practice errors |

-Pediatric residents (89) | -To help reduce errors in diabetes management and insulin administration | -Not described -Significant reduction of practice errors in contrast with pre-intervention in areas related to insulin use, communication, use of intravenous, fluids, nutrition and discharge |

-Significant reduction of practice errors in contrast with pre-intervention in areas related to insulin use, communication, use of intravenous, fluids, nutrition and discharge |

| Desimone et al., 2012/ USA (39) | -Group 1: Inpatient diabetes management program (IDMP) and Group 2: Non-IDMP -Review of glucose management and treatment order sets for both groups -Print and personal digital assistant PDA management program for group only |

-Internal Medicine Residents: -IDMP (11) -Non-IDMP (11) |

-To investigate the effectiveness of an inpatient diabetes management program on physician knowledge and patients glucose control | -Increase in inpatient diabetes knowledge score in both groups -IDMP was effective at improving physician knowledge for managing hyperglycemia in patients treated with corticosteroids or in preparation for surgical procedures |

-No difference in the frequency of glucose data in desired range between groups |

| Ena, et al., 2009/Spain (40) | -Fifteen to Twenty-minute seminar on practice recommendations by ADA -Fifteen-minute interactive discussion on applying recommendations to practice -Pocket guide and poster summarizing management |

-Emergency and Medicine Department Physicians (71) and nurses (N/A) | -To evaluate change in prescribing habits and glucose control after education in medical wards | -Willingness to use, and perception of better control with basal-bolus-correction insulin, and perception of usefulness of pocket guides and posters was rated high to somewhat high -Concern with hypoglycemia risk while using basal-bolus-correction insulin regimens was rated somewhat high -Perception of simplicity of basal-bolus-correction insulin regimens was rated neutral |

-Increase in the use of basal-bolus-correction regimens -Increase in proportion of patients with HbA1c value available -Reduction in average blood glucose on first day of admission and the day prior to discharge -Reduction of proportion of patients treated with oral hypoglycemic agents in the hospital -Reduction of the proportion of glucose levels at goal following the education intervention period |

| Herring, et al., 2013/UK (41) | -8-hour workshop -Series of group activities designed to complete a jigsaw puzzle where pieces represented different aspects of inpatient glycemic management |

-Pharmacists, nurses, healthcare assistants and junior doctors (discipline not identified) (31) | -To pilot an inter-professional education tool and its impact on healthcare professional confidence, knowledge and quality of inpatient diabetes care | -Increased confidence and knowledge in inpatient diabetes | -Reduction in management errors for hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia -Improvement of hypoglycemia management -Improvement in frequency of blood glucose monitoring -Increase in documented foot assessment -No difference in referral to diabetes specialty team - No difference in reduction of diabetes medication prescription errors |

| Horton, et al., 2015/USA (42) | -Instruction to participants on insulin dosing calculations and use of basal bolus insulin before | -Medicine residents (8) | -To assess the effects of a guideline-derived resident educational program on the use of proper insulin regimens and its impact on inpatient glycemic control and length of hospital stay | -Improvement in insulin therapy selection following instruction of guidelines | -Higher utilization of basal-plus-bolus regimen -No change in the use of sliding scale insulin alone -Reduction in mean blood glucose concentration -Reduction in length of stay -Increase in frequency of hypoglycemia - No increase in rates of severe hypoglycemia |

| Koffarnus, et al, 2016/ USA (43) | -Thirty-minute slide show presentation on ADA standards of Care | -Psychiatric attendings (N/A) | -To assess adherence to ADA Standards of Care in a psychiatric inpatient facility | -Not described | -Increased documentation of HbA1c -Increased documentation of fasting lipid profile -No difference in the frequency of documentation of fasting plasma glucose, serum creatinine, and urine microalbumin -No difference in days treated with sliding scale insulin |

| Rubin/McDonnell, 2009/USA (44) | -Lecture including the AACE inpatient diabetes care slides (Two mandatory medicine interns and three encouraged lectures for all residents) -Mandatory case-based diabetes ward rounds -Pocket cards for insulin dosing instructions and hypoglycemia management |

-Internal medicine residents (91) -Internists or hospitalists (14) -Medicine subspecialists (8) |

-To determine the effect of a year-long, multifaceted curriculum on the knowledge of medicine residents | -Improvement of knowledge scores from the PGY-1 to the PGY-2 level -No evidence of progressive increase of knowledge from PGY-2 to the PGY-3 level or among faculty |

-Not described |

| Tamler, et al., 2011/ USA (45) | -Two 90-minutes program composed of 10 cases -Forty five minutes refresher course offered several months later informed by educational gaps observed from chart reviews after initial program |

-Internal Medicine residents: --small group training (52) --online training for residents unavailable for group training (56) |

-To determine impact of case-based education in confidence and management of glycemia among residents | -Increase in knowledge and confidence in both groups (greater among interns) -Greater score improvement from baseline in the online trained group -Knowledge was maintained after refresher course |

-No difference in the management of glycemia -Increased trend of use of mealtime insulin when indicated -Increased trend of titration of insulin when indicated |

| Tamler et al., 2012/ USA (46) | 3-hour course with 10 online, case based modules for first year residents and abbreviated training for second and third-year residents repeating training followed by a refresher course (training modules evolved from original version years prior) | Internal medicine residents Course (117) |

To implement and evaluate a web-based curriculum on glycemic management | -Increased in confidence and knowledge among first time and repeat participants -A decline in knowledge was observed for topics not reinforced in refresher course |

-Increased number of blood glucose readings within target -Improved glucose control without increased hypoglycemia |

| Tamler et al., 2013/USA (47) | Web-based curriculum with narrated PowerPoint presentation and interactive quizzes | Hospitalists (22) | To determine whether an educational intervention for hospitalists previously offered to residents would improve inpatient glycemia without concomitant hypoglycemia | -Not described -Reported benefit: participants found relevance to their practice |

-Reduction of median blood glucose level - Increased in patient days within glycemic target -No increase in hypoglycemic events |

| Taylor et at, 2012/ USA (48) | One-hour interactive, case-based program incorporating a series of decision-making steps in four hospitals | Medical and Surgical residents (242) | To evaluate the impact of a targeted short intervention on residents’ confidence and quality of patient care provided | -Increase in confidence in insulin dose adjustment, use of insulin infusions, avoidance of insulin errors, treatment of severe hypoglycemia, and identification of patients requiring referral | -Reduction of prescription errors defined as not writing up insulin, prescribing wrong preparation, unclear writing, use of ‘u’ for units, and not signing prescriptions -No difference in management errors such as failure to adjust insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents for hyper or hypoglycemia -No difference in patient selection, duration, or discontinuation of insulin infusion -No difference in treatment of severe hypoglycemia, foot examination, or referral to diabetes service when indicated |

| Vaidya et al., 2011/USA (49) | Ten to fifteen minutes-ten case-based interactive computer based lesson modules | Internal Medicine residents (165) | To evaluate the effect of training program on house staff knowledge and comfort in the management of inpatient diabetes | -Increased self-reported comfort and knowledge levels in frequently encountered scenarios in diabetes management in the hospital | -No differences in use of basal-bolus insulin regimens or decreased use of sliding-scale insulin alone |

N/A: not available

RESULTS

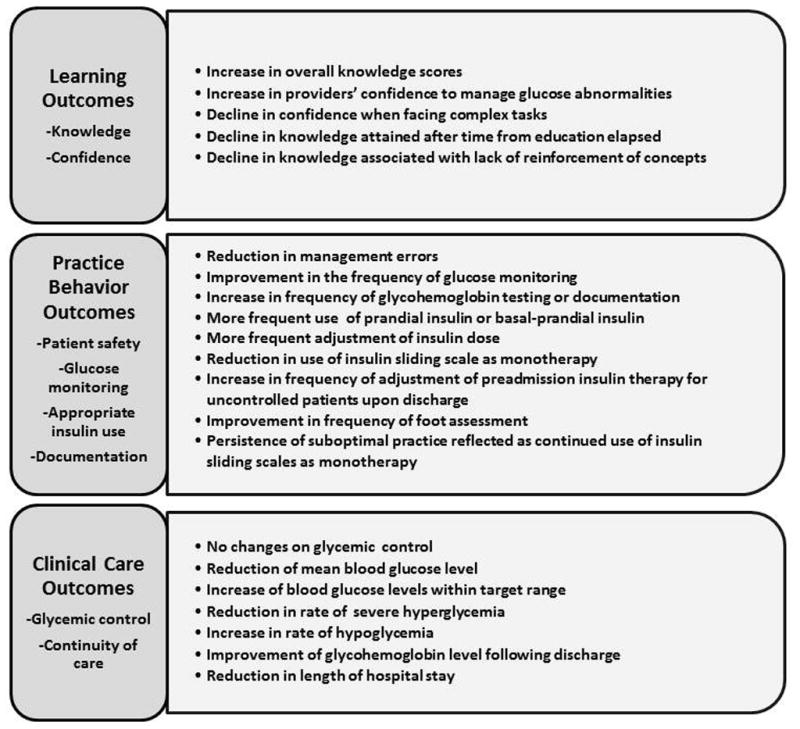

Our review of these 16 studies included at least 1,123 participants from different disciplines (34–49). These studies were conducted in different countries, including 13 in the United States, 1 in Australia, 1 in the United Kingdom, and 1 in Spain. Most participants were medicine residents; a small number were pediatric or surgical residents, and few trainees were from a discipline not specified. Some studies included a small number of hospitalists, internal medicine physicians or subspecialists, and psychiatric providers. Two studies included participants from disciplines such as pharmacy, nursing, and other allied healthcare services. Two studies did not provide the number of medicine trainees, faculty, or nurses that participated in their program. One study included junior physicians without further description of their discipline of practice. The general purpose of these various educational interventions aimed to provide education to trainees, faculty, or allied healthcare providers; to disseminate educational tools; to evaluate a new curriculum; to determine improvement of skills, knowledge, and confidence among providers; to assess adherence to guidelines; and to facilitate reduction of management errors. The pedagogical or instructional methods used varied among the studies and included one or more of the following: reading material, computer-based learning, live workshops, lectures, symposia, clinical rounds, interactive activities, pocket cards and posters, and use of electronic assisting devices. The findings reported in these articles referred to changes in knowledge, confidence, and practice behaviors among study participants and to various aspects of patient care such as glucose control, insulin selection and use, glucose monitoring and testing, patient safety, length of hospital stay, and continuity of care, as detailed in Table 1. We grouped the findings of these studies into three categories: (1) learning outcomes, (2) clinical care outcomes, and (3) practice behaviors outcomes which are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Learning and Clinical Outcomes Derived from Educational Interventions

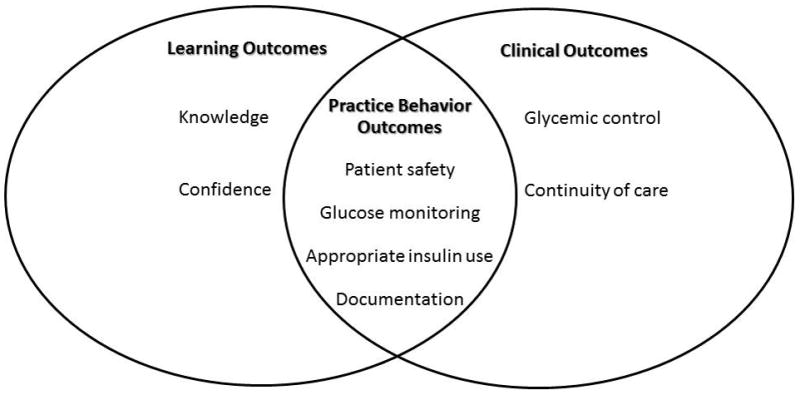

Learning outcomes included improvements in overall knowledge scores on topics pertaining to diabetes management in the hospital, sustainability of knowledge gained, and providers’ confidence in managing glycemic scenarios. Clinical care outcomes are represented by changes in blood glucose control, changes in frequency of hypoglycemia, changes in glycohemoglobin control after admission, and changes in hospital length of stay. The practice behavior outcomes, which represented findings where learning and clinical outcomes overlapped, relate to the following: management errors; frequency of glucose monitoring or glycohemoglobin result availability; insulin selection and adjustment while in the hospital or upon discharge; other health assessments, such as foot examination; and persistence of suboptimal practice behaviors, such as continued use of insulin sliding scales as a sole mode of therapy. Figure 1 depicts the intersection of learning and clinical care outcomes steering practice behaviors outcomes. One study reported only about the participants’ perspectives regarding the usefulness of the educational activity. Consistent with our article selection criteria, none of the studies reported hospital quality improvement interventions taking place concurrently with the educational initiative. None of the studies were designed to determine direct associations between providers’ knowledge or practice behaviors and their patients’ clinical outcomes. The specific findings related to participants learning outcomes, patient care outcomes, and the overlap of both outcomes as reported by each study are outlined in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Based on the learning and clinical care outcomes reported by the educational interventions reviewed in these studies, and considering the instructional methods used, our review capitalizes on learning and clinical practice perspectives that can advance the care of patients with diabetes and/or dysglycemia in the hospital.

We propose that efforts to promote learning related to the management of diabetes in the hospital setting need to consider the following: (1) application of knowledge related to inpatient glycemic management can be improved with active, situated, and participatory interactions of learners in the workplace; and (2) instruction about inpatient glycemic management needs to reach a larger population of learners.

We propose the following perspectives in order to promote alignment between education, clinical practice, use of resources, and quality of care in the hospital: (1) the management of dysglycemia in the hospital may benefit from the integration of clinical decision support strategies; and (2) education should be adopted as a formal component of hospitals’ quality planning, aiming to integrate clinical practice guidelines and to optimize diabetes care in hospitals. The following sections further explain these perspectives based on our literature review.

Application of Knowledge Related to Inpatient Glycemic Management Can Be Improved With Active, Situated, and Participatory Interactions of Learners in the Workplace

The educational programs included in this review used different methods of instruction and elicited various levels of participation among learners. One can infer that an underlying cause of lack of durability of previously acquired knowledge is the result of temporary memorization of facts facilitated by certain methods of instruction. Knowledge that is not maintained over time is likely the result of leaning out of a context of real or simulated practice. This suggests the need to align educational content and methods of instruction in order to promote recalling and application of relevant information when needed, which may in turn influence clinical practice and clinical decisions.

When learners displayed both knowledge/confidence gains and selected adequate insulin regimens (as opposed to sliding scales alone), this seemed to correlate with educational activities that provided greater hands-on experience or in a context of practice. This was evident in the study design by Baldwin and colleagues (34), in which providers had an opportunity for practice within guided clinical rounds. This notion is also supported by Ena and colleagues’ study (40), in which educational material was readily available in working areas when care decisions were required. This is relevant in the care of patients with diabetes in the hospital, considering that sliding scale insulin as monotherapy is in most cases a retroactive treatment approach that attempts to correct hyperglycemia only after it has occurred instead of preventing it. This strategy as the sole more of treatment has been proven to be a suboptimal treatment approach in comparison to basal-prandial insulin therapy, and one that can pose greater risks to patients (50, 51). Therefore, incorporating learning strategies for the instruction of glycemic control regimens where learners are included in the process of learning through participation rather than being a passive recipient of information, can pay off with desirable practice outcomes.

Instruction About Inpatient Glycemic Management Needs to Reach a Larger Population of Learners

Learners included in the majority of these studies were trainees from internal medicine residency programs (34, 36, 39, 42, 44–46, 49), while fewer participants were from other disciplines. A smaller number were faculty staff, nurses, and other allied health service providers. These findings become more relevant considering that knowledge and attitude deficits related to inpatient glycemic management have been reported in various disciplines, including general medicine, surgery, neurology, and also nursing. Furthermore, deficits are apparent among faculty, nurses, mid-level providers, and residency trainees. These deficiencies are related to limited biomedical and contextual knowledge regarding management of inpatient hyperglycemia and diabetes among providers; inattention to glycemic issues in the hospital and as patients transition home; low confidence in addressing glucose abnormalities, prescribing insulin, or educating patients regarding diabetes; failure to comply with recommended protocols; gaps in clinical decision making; and lack of familiarity with existing resources, among other factors (19–22, 24, 52, 53). Management of hyperglycemia and diabetes in hospitals requires a multidisciplinary approach where adequate communication across disciplines and among members of the clinical teams is promoted (10, 12). Therefore, inpatient diabetes educational programs need to consider the inclusion of providers within and across different healthcare disciplines. Additionally, the care of hospitalized patients with diabetes is in increasing demand, while there remains a disproportionately low supply of endocrinologists and diabetologists (54). In this context, primary admitting teams, nurses, physician assistants, and other healthcare disciplines are increasingly attending to the needs of hospitalized patients with diabetes amidst the challenges of more acute problems which may relegate glycemic management to a secondary level of care. Therefore, in order to expand on the workforce that can participate in the care of patients with diabetes in the hospital, we need to adopt educational strategies related to hospital glycemic management for providers across clinical disciplines.

Management of Dysglycemia in the Hospital May Benefit From the Integration of Clinical Decision Support Strategies

As shown by some of these reports, improvement in knowledge does not consistently correlate with achieved glucose targets (39, 45). This is likely due to the array of factors that influence glucose control in hospitals. Notoriously complex glucose management scenarios, such as corticosteroid-associated hyperglycemia and pre-operative care, seem to benefit from the use of an assistive device to provide information to clinicians and guide their practice (39). The failure to sustain clinical goals achieved as time after education elapses (40) raises the concern for the reliability and accountability of processes needed to maintain quality of patient care. Further, knowledge appears to plateau among more advanced residents and among faculty (44). As such, management of inpatient glucose and diabetes requires more than just acquiring knowledge. Gaps in knowledge can be anticipated among providers, particularly in changing clinical scenarios of varying complexity. Therefore, interventions to manage dysglycemia in the hospital should consider strategies that include education of providers but that do not exclusively depend on providers for their execution.

The use of standardized insulin order sets and management algorithms as tools can yield benefits in managing hyperglycemia (55). Embedding order sets in electronic records or in admission bundles can facilitate physicians’ utilization of existing resources. Use of electronic health records has demonstrated benefits in quality and in efficiency of care, patient safety, communication, transitions of care, and in the implementation of clinical guidelines in various healthcare fields (56–60). Benefits in hospital glycemic management are apparent by the reduction of frequency of use of insulin sliding scales as monotherapy through electronic insulin order sets and nurse-initiated prompts to providers (61) and by the reduction of rates of dysglycemia using computerized order sets (62). A systematic review of information and communication technology interventions assessed the impact on dissemination of clinical practice guidelines. As reported in this review, findings on usability of tools, knowledge, and practice behaviors varied according to the modality of interventions. The heterogeneity of studies did not allow for precise conclusion regarding application of knowledge into action. Nonetheless, there is some evidence that clinical decision support systems can favorably impact practice behaviors (63).

Education Should Be Adopted as a Formal Component of Hospitals’ Quality Planning, Aiming to Integrate Clinical Practice Guidelines and to Optimize Diabetes Care in Hospitals

Continuing medical education for healthcare professionals should be integrated as an essential component of the care of hospitalized patients with diabetes. Furthermore, it needs to be considered part of hospitals’ quality improvement planning processes.

Deficits related to hospital glycemic management can be ascribed to physicians in training as well as faculty (18, 20–22), and this is relevant given the direct role that clinicians from multiple disciplines have in the decision making process to address dysglycemia in the hospital. A common characteristic among the studies included in this review is that all studies achieved some learning and/or patient care goals. Many of the clinical outcomes associated with the different educational interventions reported in this critical review suggest that achieving goals of care and adherence to clinical practice guidelines may be facilitated by providers’ education. In these studies, the overall reductions in blood glucose levels (35, 64), the increase in number of patients achieving glycemic targets (34, 46, 64), and the improvement of hypoglycemia management (41) collectively signal advancements toward achieving better and safer glucose management. The repercussions of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia among critically ill, noncritically ill, and perioperative patients is widely recognized (10–13, 15, 65, 66). Therefore, it is necessary to strive for strategies that can promote both effectiveness and safety when managing hyperglycemia in the hospital.

An increased trend in the use of mealtime insulin, titration of insulin when warranted, (45), and avoidance of sliding scale insulin as monotherapy (34) observed in several of these studies are congruent with the recommendations of leading diabetes societies (10, 12, 67). Compelling research evidence indicates that basal-nutritional-supplemental insulin therapy is preferred over sliding scale insulin as monotherapy (15, 34, 50, 51, 68). As such, the treatment approaches facilitated by these educational interventions align with evidence-based practices. The improvement in the frequency of capillary glucose testing achieved after education (41) is congruent with the recommendation of glucose monitoring for hospitalized patients with diabetes. Bedside point-of-care glucose monitoring is advised as the preferred method of testing to guide the management of dysglycemia in the hospital, and it can facilitate identifying patients at risk for diabetes. Updating and documenting hemoglobin A1c levels is strongly advocated, not only for hospitalized patients with diabetes, but also for patients in long-term facilities. Along this line, education of faculty in a psychiatric hospital appeared to successfully facilitate this goal (43).

Reduction in management errors resulting from oversights related to insulin use (38, 41, 48) from communication issues, related to intravenous fluids or nutrition, and pertaining to discharge delays (38) were reported by these educational interventions cited. Insulin is recognized among the higher-risk medications used in the inpatient setting. Considering the risk of inpatient hypoglycemia associated with insulin use (14, 69) and the increasing accountability placed on hospitals to minimize errors and to foster better outcomes across all inpatient settings (70, 71), an attempt to eliminate insulin-related errors should be a consistent inpatient quality goal. The intensification of diabetes treatment regimens upon discharge leading to improved postdischarge glycohemoglobin and attempts for better coordination of care upon discharge resulting from providers’ education (34) address a crucial point in the transition of care of patients with diabetes. This aligns with current clinical practice recommendations (10, 12, 67) and supports the notion that education among providers can shift the pendulum towards better achievement of diabetes care beyond hospitalization. Barriers that prevent a seamless transition to and from inpatient and outpatient settings should be paid considerable attention. Ensuring that glycemic levels are communicated from inpatient to outpatient providers is a critical task in hospital medicine. Unfortunately, diabetes often remains underrecognized among hospitalized patients, in part due to inadequate documentation of hyperglycemia and/or lack of follow-up with confirmatory testing, thus potentially jeopardizing adequate continuity of care after discharge (72–74). An unfavorable outcome, such as hypoglycemia in the process of training for better glycemic control in hospitals, is not uncommon (35, 46). Hypoglycemia among hospitalized patients receiving insulin therapy is linked to increased morbidity, mortality, and utilization of hospital resources (14, 69, 75–77). This reminds us about the need to promote awareness of the risk for hypoglycemia, particularly as the clinical and/or nutritional status of patients change during hospital stay.

This review has several limitations. It includes a small number of studies, with the majority of participants representing medicine trainees, while other disciplines and faculty are less represented. Studies reporting changes in glucose control among hospitalized patients based their conclusions on retrospective glucose analyses, thus limiting any inference on the causal association between education and glucose control. None of the studies were designed to determine a direct association between domains such as knowledge, confidence, or practice behaviors of providers on the glucose control achieved among patients. While none of these studies reported concurrent quality improvement activities taking place during the time of the educational programs, the impact of other possible simultaneous interventions in these hospitals could not be completely excluded as a confounder. The rate of response of the participants to knowledge and attitude questionnaires was variable among studies, possibly introducing omission bias in the results. While this was an extensive review, it does not qualify as a systematic review according to stringent guidelines (33). For example, our search was restricted to the PubMed database; there may have been other relevant databases which were not searched.

CONCLUSION

This critical review of the literature expands our insights regarding the impact of educational efforts to advance the care of hospitalized patients with diabetes. It elaborates on learning outcomes informing a perspective that advocates for objectives and methods to promote active participation of the learner. Further, it supports the inclusion of learners from other disciplines with roles in the care of hospitalized patients with diabetes. Our perspectives on practice propose integration of clinical decisions tools in order to augment providers’ practice performance. We advocate for hospital programs that can incentivize an alignment between education and quality improvement to mirror clinical practice recommendations from leading diabetes societies.

The views presented herein may facilitate advocating and recruiting intellectual, technological, and quality improvement resources to better the care of patients with hyperglycemia and/or diabetes in the hospital. Further efforts are needed to advance criteria to optimally measure learning and clinical outcomes derived from educational interventions for diabetes in the hospital setting.

Figure 2.

Intersection of Learning, Clinical Care, and Practice Behaviours Outcomes

Acknowledgments

We thank Nancy Adams, Associate Director and Coordinator for education and instruction at the Harrell Health Science Library of Penn State College of Medicine and Hershey Medical Center for her contribution to an exhaustive literature search. This work was partially supported by a career development award from the National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Disease (K23DK107914-01) and by The Eberly Medical Research Innovation Fund (APL). Author contributions were as follows. A.P.L.: conception, design, acquisition, review and analysis of articles, drafting, revision and approval of manuscript. P.H.: design, revision of work, manuscript editing, and final approval. G.U.: consultation regarding analysis and interpretation, manuscript editing, and final approval. A.P.L. is the guarantor of this work and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data presented. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and may not represent the views of the National Institutes of Health, the Pennsylvania State University, or Emory University.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no multiplicity of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention C. [Accessed February 25, 2016];Diabetes Public Health Resource. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/dmany/fig3.htm.

- 2.Bersoux S, Cook CB, Kongable GL, Shu J, Zito DR. Benchmarking glycemic control in u.s. Hospitals. Endocr Pract. 2014;20:876–883. doi: 10.4158/EP13516.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boord JB, Greevy RA, Braithwaite SS, et al. Evaluation of hospital glycemic control at US academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:35–44. doi: 10.1002/jhm.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook CB, Kongable GL, Potter DJ, Abad VJ, Leija DE, Anderson M. Inpatient glucose control: a glycemic survey of 126 U.S. hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:E7–E14. doi: 10.1002/jhm.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wexler DJ, Meigs JB, Cagliero E, Nathan DM, Grant RW. Prevalence of hyper- and hypoglycemia among inpatients with diabetes: a national survey of 44 U.S. hospitals. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:367–369. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zapatero A, Gomez-Huelgas R, Gonzalez N, et al. Frequency of hypoglycemia and its impact on length of stay, mortality, and short-term readmission in patients with diabetes hospitalized in internal medicine wards. Endocr Pract. 2014;20:870–875. doi: 10.4158/EP14006.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frisch A, Chandra P, Smiley D, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of hyperglycemia in the perioperative period in noncardiac surgery. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1783–1788. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falciglia M, Freyberg RW, Almenoff PL, D’Alessio DA, Render ML. Hyperglycemia-related mortality in critically ill patients varies with admission diagnosis. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:3001–3009. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b083f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furnary AP, Wu Y. Clinical effects of hyperglycemia in the cardiac surgery population: the Portland Diabetic Project. Endocr Pract. 2006;12(Suppl 3):22–26. doi: 10.4158/EP.12.S3.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moghissi ES, Korytkowski MT, DiNardo M, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1119–1131. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pichardo-Lowden A, Gabbay RA. Management of hyperglycemia during the perioperative period. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12:108–118. doi: 10.1007/s11892-011-0239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umpierrez GE, Hellman R, Korytkowski MT, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non-critical care setting: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:16–38. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umpierrez GE, Isaacs SD, Bazargan N, You X, Thaler LM, Kitabchi AE. Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in-hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:978–982. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finfer S, Liu B, Chittock DR, et al. Hypoglycemia and risk of death in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1108–1118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pichardo-Lowden AR, Fan CY, Gabbay RA. Management of hyperglycemia in the non-intensive care patient: featuring subcutaneous insulin protocols. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:249–260. doi: 10.4158/EP10220.RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Chou R, Snow V, Shekelle P. Use of intensive insulin therapy for the management of glycemic control in hospitalized patients: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:260–267. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-4-201102150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beliard R, Muzykovsky K, Vincent W, 3rd, Shah B, Davanos E. Perceptions, Barriers, and Knowledge of Inpatient Glycemic Control: A Survey of Health Care Workers. J Pharm Pract. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0897190014566309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheekati V, Osburne RC, Jameson KA, Cook CB. Perceptions of resident physicians about management of inpatient hyperglycemia in an urban hospital. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:E1–8. doi: 10.1002/jhm.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook CB, Jameson KA, Hartsell ZC, et al. Beliefs about hospital diabetes and perceived barriers to glucose management among inpatient midlevel practitioners. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34:75–83. doi: 10.1177/0145721707311957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook CB, McNaughton DA, Braddy CM, et al. Management of inpatient hyperglycemia: assessing perceptions and barriers to care among resident physicians. Endocr Pract. 2007;13:117–124. doi: 10.4158/EP.13.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costantini TW, Acosta JA, Hoyt DB, Ramamoorthy S. Surgical resident and attending physician attitudes toward glucose control in the surgical patient. Am Surg. 2008;74:993–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pichardo-Lowden A, Kong L, Haidet P. Knowledge, attitudes, and decision making in hospital glycemic management: are faculty up to speed? Endocr Pract. 2015;21:307–322. doi: 10.4158/EP14246.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coan KE, Schlinkert AB, Beck BR, et al. Clinical inertia during postoperative management of diabetes mellitus: relationship between hyperglycemia and insulin therapy intensification. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:880–887. doi: 10.1177/193229681300700410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffith ML, Boord JB, Eden SK, Matheny ME. Clinical inertia of discharge planning among patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2019–2026. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knecht LA, Gauthier SM, Castro JC, et al. Diabetes care in the hospital: is there clinical inertia? J Hosp Med. 2006;1:151–160. doi: 10.1002/jhm.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giangola J, Olohan K, Longo J, Goldstein JM, Gross PA. Barriers to hyperglycemia control in hospitalized patients: a descriptive epidemiologic study. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:813–819. doi: 10.4158/EP.14.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufman DM, Mann KV. Teaching and learning in medical education: how theory can inform practice. In: Swanwick T, editor. Understanding Medical Education Evidence, theory and practice. London, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 16–36. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris C, Blaney D. Work-based learning. In: Swanwick T, editor. Understanding Medical Education Evidence, theory and practice. London, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pitts J. Portfolios, personal development and reflective practice. In: Swanwick T, editor. Understanding Medical Education Evidence, theory and practice. London, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teunissen PW, Wilkinson TJ. Learning and teaching in workplaces. In: Tim Dornan KM, Scherpbier Albert, Spencer John, editors. Medical Education, Theory and Practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2011. pp. 194–209. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambrose SA, Bridges MW, Lovett MC, DiPietro M, Norman MK. How learning works. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Information NCfB. US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health; 2016. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, University of Oxford. [Accessed January 6, 2017];PRISMA-TRANSPARENT REPORTING of SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS and META-ANALYSES. Available at: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

- 34.Baldwin D, Villanueva G, McNutt R, Bhatnagar S. Eliminating inpatient sliding-scale insulin: a reeducation project with medical house staff. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1008–1011. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chehade JM, Sheikh-Ali M, Alexandraki I, House J, Mooradian AD. The effect of healthcare provider education on diabetes management of hospitalised patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:917–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conn JJ, Dodds AE, Colman PG. The transition from knowing to doing: teaching junior doctors how to use insulin in the management of diabetes mellitus. Med Educ. 2003;37:689–694. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook CB, Wilson RD, Hovan MJ, Hull BP, Gray RJ, Apsey HA. Development of computer-based training to enhance resident physician management of inpatient diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:1377–1387. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desalvo DJ, Greenberg LW, Henderson CL, Cogen FR. A learner-centered diabetes management curriculum: reducing resident errors on an inpatient diabetes pathway. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2188–2193. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Desimone ME, Blank GE, Virji M, et al. Effect of an educational Inpatient Diabetes Management Program on medical resident knowledge and measures of glycemic control: a randomized controlled trial. Endocr Pract. 2012;18:238–249. doi: 10.4158/EP11277.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ena J, Casan R, Lozano T, Leach A, Algado JT, Navarro-Diaz FJ. Long-term improvements in insulin prescribing habits and glycaemic control in medical inpatients associated with the introduction of a standardized educational approach. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;85(2):159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herring R, Pengilley C, Hopkins H, et al. Can an interprofessional education tool improve healthcare professional confidence, knowledge and quality of inpatient diabetes care: a pilot study? Diabet Med. 2013;30:864–870. doi: 10.1111/dme.12153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horton WB, Weeks AQ, Rhinewalt JM, Ballard RD, Asher FH. Analysis of a Guideline-Derived Resident Educational Program on Inpatient Glycemic Control. South Med J. 2015;108(10):596–598. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koffarnus RL, Mican LM, Lopez DA, Barner JC. Evaluation of an inpatient psychiatric hospital physician education program and adherence to American Diabetes Association practice recommendations. American J Health-Syst Pharm. 2016 doi: 10.2146/sp150037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rubin DJ, McDonnell ME. Effect of a diabetes curriculum on internal medicine resident knowledge. Endocr Pract. 2010 doi: 10.4158/EP09275.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamler R, De G, MS, et al. Effect of case-based training for medical residents on inpatient glycemia. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1738–1740. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tamler R, Green De Skamagas M, Breen TL, et al. Durability of the effect of online diabetes training for medical residents on knowledge, confidence, and inpatient glycemia. Journal of diabetes. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1753-0407.2012.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamler R, Dunn AS, Green DE, et al. Effect of online diabetes training for hospitalists on inpatient glycaemia. Diabet Med. 2013;30:994–998. doi: 10.1111/dme.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor CG, Morris C, Rayman G. An interactive 1-h educational programme for junior doctors, increases their confidence and improves inpatient diabetes care. Diabetic medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaidya A, Hurwitz S, Yialamas M, Min L, Garg R. Improving the management of diabetes in hospitalized patients: the results of a computer-based house staff training program. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14:610–618. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Jacobs S, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing general surgery (RABBIT 2 surgery) Diabetes Care. 2011;34:256–261. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Zisman A, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 trial) Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2181–2186. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coats A, Marshall D. Inpatient hypoglycaemia: a study of nursing management. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Modic MB, Vanderbilt A, Siedlecki SL, Sauvey R, Kaser N, Yager C. Diabetes management unawareness: what do bedside nurses know? [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vigersky RA, Fish L, Hogan P, Stewart A, et al. The clinical endocrinology workforce: current status and future projections of supply and demand. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kennihan M, Zohra T, Devi R, Srinivasan C, et al. Individualization through standardization: electronic orders for subcutaneous insulin in the hospital. Endocrine Practice. 2012 doi: 10.4158/EP12107.RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bates DW, Leape LL, Cullen DJ, et al. Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA. 1998;280:1311–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leighton H, Kianfar H, Serynek S, Kerwin T. Effect of an electronic ordering system on adherence to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for cardiac monitoring. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2013;12:6–8. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e318270787c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Radecki RP, Sittig DF. Application of electronic health records to the Joint Commission’s 2011 National Patient Safety Goals. JAMA. 2011;306:92–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silow-Carroll S, Edwards JN, Rodin D. Using electronic health records to improve quality and efficiency: the experiences of leading hospitals. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2012;17:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gonzalo JD, Yang JJ, Stuckey HL, Fischer CM, Sanchez LD, Herzig SJ. Patient care transitions from the emergency department to the medicine ward: evaluation of a standardized electronic signout tool. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26:337–347. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shabbir H, Stein J, Tong D, Bhalla V, Wang A. A real-time nursing intervention reduces dysglycemia and improves best practices in noncritically ill hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:E15–20. doi: 10.1002/jhm.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schnipper JL, Liang CL, Ndumele CD, Pendergrass ML. Effects of a computerized order set on the inpatient management of hyperglycemia: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Endocr Pract. 2010;16:209–218. doi: 10.4158/EP09262.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Angelis GA, Ohoo Davies BA, Ohoo King JA, et al. Information and Communication Technologies for the Dissemination of Clinical Practice Guidelines to Health Professionals: A Systematic Review. JMIR Med Educ. 2016;2(2) doi: 10.2196/mededu.6288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tamler R, Dunn As Green DE, Skamagas M, et al. Effect of online diabetes training for hospitalists on inpatient glycaemia. Diabetic medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1111/dme.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:449–461. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1359–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Diabetes Care in the Hospital. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 1):S99–104. doi: 10.2337/dc16-S016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Umpierrez GE, Palacio A, Smiley D. Sliding scale insulin use: myth or insanity? Am J Med. 2007;120:563–567. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, et al. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1283–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Belmont E, Haltom CC, Hastings DA, et al. Analysis & commentary: A new quality compass: hospital boards’ increased role under the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:1282–1289. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Commission TJ. [Accessed July 29, 2016];Certification in Inpatient Diabetes. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/certification/inpatient_diabetes.aspx.

- 72.Ladeira RT, Simioni AC, Bafi AT, Nascente AP, Freitas FG, Machado FR. Diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance are underdiagnosed in intensive care units. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2012;24:347–351. doi: 10.1590/S0103-507X2012000400009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shore S, Borgerding JA, Gylys-Colwell I, et al. Association between hyperglycemia at admission during hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction and subsequent diabetes: insights from the veterans administration cardiac care follow-up clinical study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:409–418. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Levetan CS, Passaro M, Jablonski K, Kass M, Ratner RE. Unrecognized diabetes among hospitalized patients. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:246–249. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murad MH, Coburn JA, Coto-Yglesias F, et al. Glycemic control in non-critically ill hospitalized patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;97:49–58. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Turchin A, Matheny ME, Shubina M, Scanlon JV, Greenwood B, Pendergrass ML. Hypoglycemia and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes hospitalized in the general ward. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1153–1157. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wiener RS, Wiener DC, Larson RJ. Benefits and risks of tight glucose control in critically ill adults: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:933–944. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]