Abstract

In September 2013, the Hawaii Department of Health (HDOH) was notified of seven adults who developed acute hepatitis after taking OxyELITE Pro™, a weight loss and sports dietary supplement. CDC assisted HDOH with their investigation, then conducted case-finding outside of Hawaii with FDA and the Department of Defense (DoD).

We defined cases as acute hepatitis of unknown etiology that occurred from April 1, 2013, through December 5, 2013, following exposure to a weight loss or muscle-building dietary supplement, such as OxyELITE Pro™. We conducted case-finding through multiple sources, including data from poison centers (National Poison Data System [NPDS]) and FDA MedWatch.

We identified 40 case-patients in 23 states and two military bases with acute hepatitis of unknown etiology and exposure to a weight loss or muscle building dietary supplement. Of 35 case-patients who reported their race, 15 (42.9%) reported white and 9 (25.7%) reported Asian. Commonly reported symptoms included jaundice, fatigue, and dark urine. Twenty-five (62.5%) case-patients reported taking OxyELITE Pro™. Of these 25 patients, 17 of 22 (77.3%) with available data were hospitalized and 1 received a liver transplant. NPDS and FDA MedWatch each captured seven (17.5%) case-patients.

Improving the ability to search surveillance systems like NPDS and FDA MedWatch for individual and grouped dietary supplements, as well as coordinating case-finding with DoD, may benefit ongoing surveillance efforts and future outbreak responses involving adverse health effects from dietary supplements. This investigation highlights opportunities and challenges in using multiple sources to identify cases of suspected supplement associated adverse events. Published 2016. This article is a U.S. Government work and is in the public domain in the USA.

Keywords: Supplement, hepatitis, OxyELITE Pro

Introduction

Dietary supplements are commonly used in the United States.[1,2] Some populations, such as military personnel, are more likely to use certain types of dietary supplements, such as weight loss or sports supplements, than the general population.[3] Some of these dietary supplements, particularly herbal products and those used for performance enhancement, have been associated with liver injury.[4–6] No comprehensive surveillance system is available for dietary supplement-induced liver injury, so information regarding supplement-induced liver injury comes from case reports and series, outbreak investigations, prospective registries, and voluntary reporting to FDA MedWatch and poison centers.[7]

On September 9, 2013, clinicians at a single tertiary care hospital in Hawaii notified the Hawaii Department of Health (HDOH) of seven patients who presented with severe acute hepatitis and fulminant liver failure of unknown etiology.[8] Abnormal laboratory findings included markedly elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine aminotransferase [ALT]), as well as total bilirubin. Testing for infectious agents, including hepatitis serologies, was negative; however, clinicians noted that all seven patients consumed OxyELITE Pro™, a weight loss or sports dietary supplement. On September 27, 2013, staff from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) joined HDOH to assist with their investigation. Case-finding efforts in Hawaii identified 52 case-patients with acute hepatitis of unknown etiology who had ingested a dietary supplement during the 60 days prior to illness onset. These case-patients, the majority of whom consumed OxyELITE Pro™, are described elsewhere.[9] Based on the preliminary findings from the Hawaii investigation, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initiated an investigation into the manufacture and distribution of OxyELITE Pro™. Case-patients reported using OxyELITE Pro™ products from multiple lots, and a trace back investigation found each of these lots was distributed to states in addition to Hawaii. Due to the nationwide distribution of OxyELITE Pro™, CDC, in collaboration with FDA and U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), initiated case-finding in the United States outside of Hawaii for additional cases of acute hepatitis of unknown etiology and exposure to a weight loss or muscle building dietary supplement. This manuscript describes the different sources through which we identified suspected case-patients and summarizes the presenting signs and symptoms, exposures, and laboratory data from these case-patients.

Methods

We defined a case as acute hepatitis of unknown etiology that developed between April 1, 2013, and December 5, 2013, in a non-Hawaii resident who consumed a dietary supplement marketed for weight loss or muscle building in the 60 days prior to illness onset. Case-patients had 1) an ALT value ≥ four times the upper limit of normal (approximately 160 international units per liter, IU/L); 2) a total bilirubin level ≥ two times the upper limit of normal (approximately 2.5 milligrams per deciliter, mg/dL); 3) a negative viral hepatitis panel; 4) hepatic imaging (i.e., ultrasound, CT scan, MRI) not consistent with alternative etiologies of non-viral hepatitis (e.g., cholelithiasis); 5) no recent hypotensive shock or septic episodes; 6) no pre-existing diagnosis of a chronic liver disease such as autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, Wilson’s disease, or hemochromatosis; and 7) no chronic alcohol abuse documented in their medical record. The only difference between our case definition and the one used in the Hawaii investigation was that we restricted our case definition to non-Hawaii residents.[9] We used four distinct approaches to identify potential cases —National Poison Data System (NPDS), FDA MedWatch, a national call for cases, and DoD case finding. Case-finding from NPDS and FDA MedWatch was restricted to cases involving OxyELITE Pro™. Below are descriptions of the four approaches used.

NPDS — NPDS collects information from all calls received by U.S. poison centers.[10] When an individual or healthcare provider calls to report an exposure to a product, poison center staff collects information on the exposure and assigns a unique, product-specific numerical code for the exposure. Since dietary supplements are coded individually and no product code encompasses all dietary supplements, we included calls involving only the product code for OxyELITE Pro™. We retrospectively searched NPDS for all calls received between April 1, 2013, and September 25, 2013, in which a caller reported an exposure to OxyELITE Pro™ and had an elevated ALT or total bilirubin. We selected April 1, 2013, based on the earliest exposure among the initial seven patients reported to HDOH. We conducted prospective case-finding from September 30, 2013, through December 5, 2013, at which point we ceased surveillance given the most recent illness onset date of November 3, 2013.

MedWatch — FDA MedWatch is a system for consumers, patients, and healthcare providers to report adverse events associated with a variety of products, including medications, medical devices, and supplements.[11] FDA searched MedWatch for reports of adverse health effects associated with OxyELITE Pro™ and collected medical records for select patients for which a description of liver disease was provided, along with a history of OxyELITE Pro™ ingestion. For this analysis we included cases reported between April 1, 2013, and December 5, 2013.

National call for cases — We requested cases through a Health Alert Network advisory distributed to state and local health departments, clinicians, and public health laboratories on October 8, 2013, and a short communication in CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) on October 10, 2013.[12,13] The Health Alert Network advisory and MMWR described the preliminary results of the investigation, including that the majority of patients identified had consumed OxyELITE Pro™, and requested that clinicians report patients meeting the case definition to their local or state health department and FDA MedWatch. We also sent a call for cases to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). To facilitate case reports, CDC established a hotline for healthcare providers to report cases of acute hepatitis of unknown etiology associated with consumption of a weight loss or muscle building dietary supplement through December 5, 2013.

DoD case finding — Given the prevalence of dietary supplement use among active duty military personnel, DoD performed active surveillance for cases by using the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), which is maintained by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (AFHSC).[14,15] The DMSS was used to identify a cohort of U.S. active duty military personnel and other beneficiaries who had ALT and total bilirubin values consistent with the case definition and had an ICD-9 diagnosis of acute or unspecified hepatitis from April 1, 2013, through December 5, 2013. Potential cases were excluded if they had a diagnosis or laboratory evidence of viral, bacterial, or pre-existing chronic hepatitis. DoD personnel then contacted these individuals to determine whether they had exposure to a dietary supplement marketed for weight loss or muscle building or had any previous medical history that would exclude them as a case. In addition, each service put out a call for cases through their public health centers asking for any case of liver injury without a clear etiology.

Individuals meeting the case definition were administered a questionnaire which focused on demographics; presence and timing of signs and symptoms; previous medical history; any use of prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, and dietary supplements in the 60 days prior to illness onset; risk factors for liver injury (e.g., Tylenol [acetaminophen] and ethanol use) in the 60 days prior to illness onset; and outcomes including hospitalization, liver transplantation, and death. DoD personnel administered a modified version of the questionnaire that included DoD-specific questions. We standardized race according to U.S. Census categories and categorized case-patients into the following groups — Pacific Islander, Asian, white, multiple races, and other. We asked case-patients specifically about consumption of OxyELITE Pro™ as well as all other supplements. Information on supplement use included supplement name, serving sizes and frequency, dates of use, reasons for use, and locations of purchase. For case-patients with available medical charts, we abstracted results for autoimmune markers and peak laboratory values associated with liver injury. We reviewed case reports from the different data sources and identified potential duplicate reports based on demographic data. We then compared the data in these potential duplicates, rectified any discrepancies, and confirmed the final data with the state health departments and DoD.

We entered data from the questionnaire and chart abstraction into a Microsoft Excel database and calculated frequencies and proportions of reported values and responses using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Case reporting

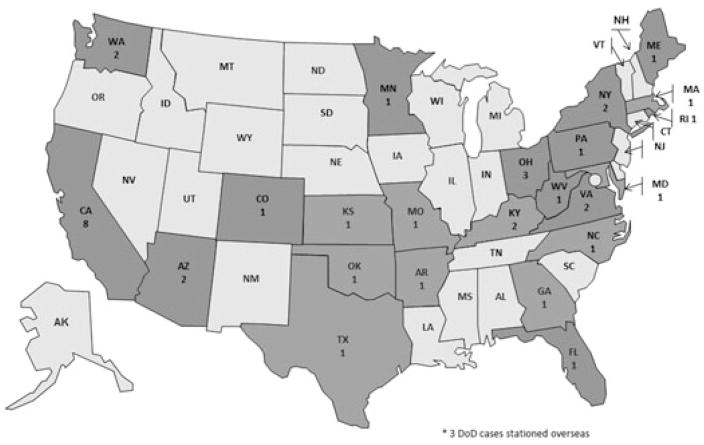

We received 86 possible case reports: 40 met the case definition; 27 did not meet the case definition; and 19 did not have enough information to determine their case status. The 40 case-patients lived in 23 states and two military bases outside the United States (Fig. 1). Case-patients were identified through the DoD (n = 21; 52.5%), NPDS (n = 7; 17.5%), FDA MedWatch (n = 7; 17.5%), state or local health departments (n = 3; 7.5%), transplant specialists (n = 1; 2.5%), and the CDC hotline (n = 1; 2.5%). Seven (17.5%) of the 40 case-patients had questionnaire and medical chart data; an additional 30 (75.0%) case-patients had either medical chart or questionnaire data, and three (7.5%) case-patients had basic data collected from the case report form (Table 1).

Figure 1.

State of Residence for Case-patients — United States, 2013, n = 40

Table 1.

Source of Case Report by Source of Data Collection — United States, 2013

| Source | Questionnaire and medical chart | Questionnaire | Medical chart | Case report form | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department of Defense | - | 21 | - | - | 21 |

| Food and Drug Administration MedWatch | 1 | - | 5 | 1 | 7 |

| National Poison Data System | 2 | 3 | - | 2 | 7 |

| State Health Departments | 3 | - | - | - | 3 |

| Transplant Specialists | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Hotline | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Total | 7 | 25 | 5 | 3 | 40 |

Demographics and presenting illness

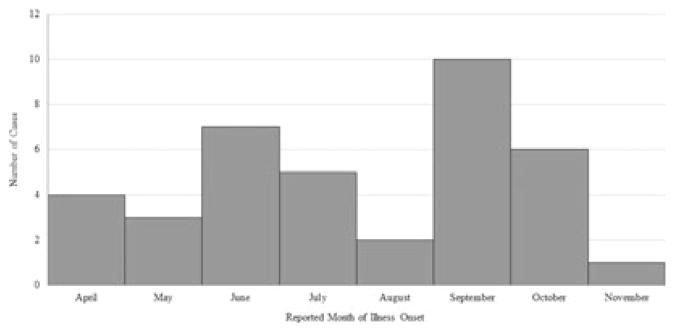

Mean age of the 40 case-patients was 33.9 years, with a range of 20–51 years. Twenty-four (60.0%) of the 40 case-patients were male. Thirty-five of the 40 case-patients reported a race, most commonly white (n = 15; 42.9%), Asian (n = 9; 25.7%), and Pacific Islander (n = 5; 14.3%) (Table 2). The median body mass index (BMI) for the 32 case-patients with available data was 28.0 kg/m2 (range: 20.6–43.1); 26 (81.3%) case-patients were categorized as overweight or obese. Illness onset dates, which were available for 38 case-patients, ranged from April 10, 2013, through November 3, 2013 (Fig. 2). The most commonly reported signs and symptoms included jaundice or scleral icterus, fatigue, dark urine, nausea, and light- or clay-colored stools (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics, presenting signs and symptoms, and laboratory tests for case-patients — United States, 2013*

| All case-patients n (%) | Case-patients exposed to OxyELITE Pro™ n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 24 (60.0) | 10 (40.0) |

| Female | 16 (40.0) | 15 (60.0) | |

| Race | White | 15 (42.9) | 4 (20.0) |

| Asian | 9 (25.7) | 9 (45.0) | |

| Pacific Islander | 5 (14.3) | 5 (25.0) | |

| Black | 3 (8.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 2 (5.7) | 1 (5.0) | |

| Multiple races | 1 (2.9) | 1 (5.0) | |

| Signs and symptoms | Jaundice | 29 (90.6) | 16 (94.1) |

| Fatigue | 29 (87.9) | 18 (100.0) | |

| Dark urine | 28 (84.9) | 17 (94.4) | |

| Nausea | 24 (75.0) | 14 (82.4) | |

| Light- or clay-colored stools | 22 (71.0) | 13 (81.3) | |

| Appetite loss | 20 (62.5) | 14 (82.4) | |

| Abdominal pain | 18 (54.6) | 10 (55.6) | |

| Laboratory Test | Reference Range † | Median Value (Range) | Median Value (Range) |

| AST, IU/L | 10–34 | 1,382 (138–2,525) | 1,500 (853–2,525) |

| ALT, IU/L | 10–40 | 1,597 (391–2,843) | 1,849 (975–2,843) |

| Alkaline phosphatase, IU/L | 44–147 | 166 (115–331) | 166 (115–331) |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.3–1.9 | 6.7 (2.4–26.4) | 6.1 (2.4–26.4) |

| INR | 0.8–1.1 | 1.2 (0.8–3.8) | 1.2 (1.0–3.8) |

The number of case-patients who responded to each question varied

Reference ranges obtained from National Library of Medicine

Figure 2.

Reported Month of Symptom Onset for Case-patients — United States, 2013, n = 38

Exposure to OxyELITE Pro™, alcohol, and medications

Twenty-five (62.5%) of 40 case-patients reported consuming OxyELITE Pro™ whereas 15 (37.5%) reported consuming only another dietary supplement in the 60 days prior to illness onset. Of the 25 case-patients who consumed OxyELITE Pro™, nearly half (n = 12; 48%) consumed at least one other supplement, and greater than a quarter (n = 7; 28%) consumed only OxyELITE Pro™ and no other supplements (Table 3). Five of the 6 cases with incomplete information on supplement use were identified through NPDS or FDA MedWatch. No additional supplements were reported in common among the 12 case-patients who consumed OxyELITE Pro™ and another dietary supplement. Of the 15 case-patients who did not consume OxyELITE Pro™, three consumed C4™, two consumed NO-Xplode™, and ten consumed some other weight loss or muscle building supplement. One case-patient who was originally reported to a poison center due to exposure to OxyELITE Pro™ subsequently reported consuming only another dietary supplement instead of OxyELITE Pro™.

Table 3.

Case-patients who Reported Consuming OxyELITE Pro™ by Source of Identification and Other Supplement Use — United States, 2013 (n = 25)

| Identified through NPDS or FDA MedWatch n (%) | Identified by DoD, state health department, or CDC Hotline n (%) | Overall n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumed only OxyELITE Pro™ | 3 (23.1) | 4 (33.3) | 7 (28.0) |

| Consumed OxyELITE Pro™ and another supplement | 5 (38.5) | 7 (58.3) | 12 (48.0) |

| Incomplete information on supplement use other than OxyELITE Pro™ | 5 (38.5) | 1 (8.3) | 6 (24.0) |

Among the 25 case-patients exposed to OxyELITE Pro™, 17 provided a reason for use: 10 (58.8%) to lose weight; four (23.5%) to improve athletic performance; two (11.8%) to increase energy; and one (5.9%) to increase muscle mass. For the 17 case-patients who reported their serving size, all consumed from one to three tablets or scoops per day, which was consistent with manufacturer recommendations. For the 19 case-patients who could remember when they started consuming OxyELITE Pro™, the median duration of OxyELITE Pro™ use prior to illness onset was 55 days (range:2–477 days).

Twenty-three (71.9%) of 32 case-patients with available data reported drinking any alcohol in the two months before illness onset. Twelve (66.7%) of 18 case-patients reported consuming two or fewer servings of alcohol at each sitting. Of the 12 case-patients who used a prescription or over-the-counter medication in the two months prior to illness onset, two (16.7%) reported taking acetaminophen “a few times a month,” and one (8.3%) reported taking ibuprofen “a few times per week.”

Laboratory Data

Median laboratory values at the peak of illness are presented in Table 2, with markedly elevated AST, ALT, and total bilirubin levels. Two (25%) of the eight case-patients tested for antinuclear antibody (ANA) had positive tests and one of five (20%) tested for anti-smooth muscle antibody had a positive test. One of three case-patients (33%) tested for F-actin antibody had a positive test and another (33%) had a weakly positive test. One of five (20%) case-patients tested for anti-mitochondrial antibody had positive tests and both case-patients tested for anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody had negative tests. Twelve (63%) of 19 case-patients with available data required a liver biopsy. For the three case-patients with liver biopsy data available, two (67%) had histopathological changes compatible with drug-induced liver injury and autoimmune features and one (33%) case-patient had non-specific findings.

Hospitalization and Outcome

Twenty-six (70.3%) of 37 case-patients with available data and 17 (77.3%) of 22 patients exposed to OxyELITE Pro™ with available data were hospitalized. Three (27.3%) of 11 case-patients with available data received N-acetylcysteine and four (36.4%) of 11 case-patients with available data received corticosteroids. Of the 25 patients exposed to OxyELITE Pro™, 1 (5.9%) of 17 with available data received a liver transplant. No case-patients died.

Discussion

Forty case-patients, including 25 case-patients who consumed OxyELITE Pro™, in 23 states and two military bases outside the United States developed acute hepatitis between April 1, 2013, and December 5, 2013 following consumption of a weight loss or sports dietary supplement. Viral hepatitis panels were reported to be negative for each case-patient, and case-patients did not report risk factors such as routine acetaminophen use in the 60 days prior to illness onset. This investigation (40 total case-patients; 25 consumed OxyELITE Pro™) and the Hawaii investigation (52 total case-patients; 44 consumed OxyELITE Pro™) identified a combined total of 92 case-patients, of whom 69 consumed OxyELITE Pro™.[9] Of these 69 case-patients who consumed OxyELITE Pro™, 32 required hospitalization, 3 required liver transplants, and 1 died.

Prior to our investigation, FDA had received reports of acute adverse health effects associated with the use of a formulation of OxyELITE Pro™ containing 1,3-dimethylamylamine (DMAA).[16] A study published in 2014 documented acute liver injury in seven active duty service members who had consumed a formulation of OxyELITE Pro™ labeled as containing DMAA.[17] The manufacturer released a DMAA-free formulation of OxyELITE Pro™ that included aegeline in early 2013.[18] After FDA notified the manufacturer that it had failed to inform FDA of the use of aegeline, which was determined to be a new dietary ingredient, the manufacturer recalled aegeline-containing formulations of OxyELITE Pro™ in November 2013.

Dietary supplements and medications associated with liver injury appear to do so through two main mechanisms: either a predictable, dose-dependent toxic effect from a medication (e.g., acetaminophen) or a less predictable, immuno-allergic, idiosyncratic reaction to an ingredient of the product.[19] Although the exact incidence of liver injury associated with dietary supplements is unknown, a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury identified dietary supplements as the cause of liver injury in 130 (15.5%) of 839 consecutively enrolled patients.[5]

Drug- or herb-induced liver injury can be a difficult diagnosis given the absence of safety data on many ingredients contained in these products; the presence of co-exposures potentially associated with liver injury including medications, supplements, and alcohol; interactions among the multiple ingredients in products and drugs; and the lack of a definitive laboratory test for drug-induced liver injury. Although several clinical diagnostic criteria have been published, there is no standardized algorithm to diagnose drug-induced liver injury.[7] Instead, the diagnosis is one of exclusion —it relies on a temporal association of exposure followed by the development of signs and symptoms, and more importantly, the exclusion of other causes of liver injury.[7,20] Therefore, in this investigation we chose a specific case definition to exclude other causes of liver injury such as viral hepatitis; pre-existing autoimmune hepatitis; chronic alcohol use; and chronic liver diseases.

Since dietary supplements often contain multiple ingredients, some with unknown safety profiles and most with unknown interactions, determining the etiologic agent and mechanism of liver injury associated with these products is difficult. A single, definitive etiologic agent is not typically identified in investigations of liver injury associated with a supplement.[21,22] As part of the Hawaii investigation, FDA performed both a general analytic laboratory screen and targeted testing of OxyELITE Pro™ for potentially hepatotoxic agents.[9,18] The testing confirmed the ingredients listed on the label and did not identify any known hepatotoxic agents, so the specific causative ingredient remains unknown. The absence of a known hepatotoxic agent identified on testing may suggest either the presence of a less common hepatotoxic agent that was not tested for, an idiosyncratic reaction to one of the listed ingredients, or a reaction to the combination of ingredients in the product. In addition to the product testing, FDA performed a trace back of OxyELITE Pro™ but did not identify a unique lot common to case-patients in the Hawaii investigation.[9,18] Compared to the Hawaii investigation, where 52 case-patients were identified, we identified 40 case-patients in several states, with California being the only state with more than 3 cases. The reason for this apparent clustering of case-patients in Hawaii without any clustering of case-patients in the continental United States remains unclear.

Our investigation demonstrated characteristics consistent with previous reports of drug-induced liver injury. In a prospective study of 839 consecutively enrolled patients with suspected drug-induced liver injury, 60% of patients were female and the median duration of supplement use was 30 days for non-bodybuilding supplements and 43.5 days for bodybuilding supplements.[5] In our investigation 40% of the patients were female and the median duration of supplement use was 55 days. Similar to our investigation and the investigation in Hawaii, case-patients in some prior investigations of drug- or herb-induced liver injury reported consuming the serving sizes recommended by the manufacturers.[23,24] The increases in ALT, AST, and total bilirubin with only a borderline elevation in alkaline phosphatase observed in our investigation suggest a hepatocellular pattern of liver injury, which is often observed in drug- or herb-induced liver injury.[4,25]

In our study, 25.7% of the 35 individuals with available race data reported Asian as their race compared to 4.8% of the 2010 U.S. population.[26] In a previous study of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury, Asians were also over-represented, comprising 6.8% of the case-patients compared to 3.6% of the 2000 U.S. population.[25] Whether this racial distribution can be attributed to purchasing practices, genetic differences suggesting that Asians may be at higher risk for drug-induced liver injury, cultural practices placing Asians at higher risk for exposure to a hepatotoxic agent, or some other unidentified factor remains unclear. A nationally representative survey documented that individuals from multiple races and Asians had the highest rates of dietary supplement use, with 24.6% of Asians reporting supplement use.[27] In a prospective study of 660 patients diagnosed with drug-induced liver injury by the Drug Induced Liver Injury Network, Asian race was a risk factor for both liver transplantation and death within six months of diagnosis. The reason for this finding is unclear, but the authors postulate that Asians may: 1) have greater susceptibility to drug-induced liver injury; 2) present later in the course of illness; or 3) have impaired liver regeneration.[28]

The significance of the positive autoimmune antibodies in some of our case-patients is also unclear. Prior studies have documented autoimmune antibodies such as ANA in cases of drug-induced liver injury. A prospective, multi-center study in the United States documented that 19 (24%) of 79 case-patients with drug-induced liver injury tested for autoimmune antibodies had positive tests.[25] In addition to drug-induced liver injury, these antibodies have been documented in all-cause liver failure, but have not been associated with a particular toxic etiology. Whether these antibodies serve a role in the immunoallergic pathogenesis underlying the idiosyncratic liver injury or if they are a consequence of the liver injury is uncertain.[25,29]

Since no specific surveillance system for drug-induced liver injury exists, we had to use multiple sources for case ascertainment. Three of these sources (NPDS, MedWatch, and the national call for cases) relied on voluntary reporting of cases. The Institute of Medicine estimates that less than half of all poisonings are reported to poison centers, so reports to poison centers may underestimate the true number of cases.[30] Our approach was subject to several limitations. Due to the lack of more generic codes or product terms, we searched NPDS using only the OxyELITE Pro™ product-specific code and FDA searched MedWatch for cases associated with only OxyELITE Pro™. Therefore, case-finding in NPDS and MedWatch was limited to those persons with exposure to OxyELITE Pro™. This inability to identify cases in NPDS and MedWatch with exposure to dietary supplements other than OxyELITE Pro™ resulted in an over-representation of OxyELITE Pro™ use among cases. The identification of cases associated with other dietary supplements may have yielded additional information regarding risk factors for illness. Since information on dietary supplement product used was self-reported, individuals may have incorrectly identified or may not have remembered the supplement they were taking. We attempted to exclude the major causes of acute hepatitis (e.g., viral hepatitis, acetaminophen) through the case definition, questionnaire, and chart abstraction; however, in many cases, we did not have access to complete medical records which might have provided additional information about the cause of liver injury.

We based our case definition on the moderate severity grade developed by the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network.[31] The strict case definition likely limited our investigation to those case-patients more severely affected and underestimated the true number of cases. Another factor that potentially resulted in underreporting is that only an estimated 45% of U.S. adults who use dietary supplements report the products to their healthcare provider.[32] Therefore, if a patient presented to a healthcare provider with acute hepatitis of unknown etiology and that provider was unaware of the patient’s supplement use, the healthcare provider would be unable to report the patient as a case. Although none of the case-patients reported excessive alcohol or acetaminophen consumption, it cannot be determined as to whether their rates of use may have contributed to liver injury. In addition, the descriptive data in our analysis limited our ability to explore specific risk factors for developing acute hepatitis. The exact number of individuals who consume specific supplements, such as OxyELITE Pro™, and the incidence of supplement-induced liver injury are unknown. As such, we cannot quantify the baseline number of dietary supplement-induced liver injuries in the United States, nor can we determine for certain if the overall number of cases of acute hepatitis identified in this investigation is greater than what would be expected based on background incidence.

We recommend that clinicians and supplement users be aware of the potential for adverse health effects from using such products and report adverse health effects to FDA MedWatch, their local poison center, and/or their local or state department of health. We also recommend healthcare providers ask about supplement use during routine and sick visits, especially when evaluating acute hepatitis. We identified case reports through multiple sources, with NPDS and FDA MedWatch accounting for only 7 (17.5%) case reports each. Improving the ability to search surveillance systems like NPDS and FDA MedWatch for individual and grouped dietary supplements, as well as coordinating case-finding with DoD, may benefit ongoing surveillance efforts and future outbreak responses involving adverse health effects from dietary supplements. Due to the racial distribution observed in the case-finding efforts in Hawaii and in our national case-finding efforts, federal agencies are developing ways to collaborate with their partners to explore many issues, including potential genetic components of drug-induced liver injury.

Conclusion

Through multiple sources, we identified 40 persons within the United States, excluding residents of Hawaii, who developed acute hepatitis between April 1, 2013, and December 5, 2013 after consuming a weight loss or sports supplement. Of the 25 persons who reported consuming OxyELITE Pro™, 17 were hospitalized and 1 required a liver transplantation. No case-patients in our investigation died. Combining our results with the Hawaii investigation, 69 case-patients consumed OxyELITE Pro™, of whom 32 required hospitalization, 3 required liver transplants and 1 died. Given that only approximately one-third of case patients were identified by existing surveillance systems (NPDS and FDA MedWatch), improving the ability of these systems to detect cases associated with individual or groups of dietary supplements may benefit future outbreak investigations. Overall, this investigation highlights opportunities and challenges in using multiple sources to identify cases of suspected supplement associated adverse events. Surveillance and outbreak investigations involving dietary supplements should consider searching multiple data sources, including FDA MedWatch, DoD medical health records, and NPDS, for case reports.

Glossary

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- AFHSC

Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- ANA

Antinuclear antibody

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI

Body mass index

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- DMSS

Defense Medical Surveillance System

- DoD

Department of Defense

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- HDOH

Hawaii Department of Health

- INR

International normalized ratio

- IU/L

International units per liter

- kg/m2

Kilogram/meter squared

- mg/ dL

Milligram/deciliter

- MMWR

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

- NPDS

National Poison Data System

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

References

- 1.Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Lentino CV, Dwyer JT, Engel JS, Thomas PR, Betz JM, Sempos CT, Picciano MF. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003–2006. J Nutr. 2011;141:261. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.133025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanck HM, Serdula MK, Gillespie C, Galuska DA, Sharpe PA, Conway JM, Khan LK, Ainsworth BE. Use of Nonprescription Dietary Supplements for Weight Loss Is Common among Americans. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:441. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knapik JJ, Steelman RA, Hoedebecke SS, Farina EK, Austin KG, Lieberman HR. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of dietary supplement use by military personnel. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navarro VJ. Herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29:373. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navarro VJ, Barnhart H, Bonkovsky HL, Davern T, Fontana RJ, Grant L, Reddy KR, Seeff LB, Serrano J, Sherker AH, Stolz A, Talwalkar J, Vega M, Vuppalanchi R. Liver injury from herbals and dietary supplements in the US Drug Induced Liver Injury Network. Hepatology. 2014;60:1399. doi: 10.1002/hep.27317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teschke R, Schwarzenboeck A, Eickhoff A, Frenzel C, Wolff A, Schulze J. Clinical and causality assessment in herbal hepatotoxicity. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2013;12:339. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.774371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR. Review article: herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:3. doi: 10.1111/apt.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roytman MM, Porzgen P, Lee CL, Huddleston L, Kuo TT, Bryant-Greenwood P, Wong LL, Tsai N. Outbreak of severe hepatitis linked to weight-loss supplement OxyELITE Pro. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1296. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston DI, Chang A, Viray M, Chatham-Stephens K, He H, Taylor E, Wong LL, Schier J, Martin C, Fabricant D, Salter M, Lewis L, Park SY. Hepatotoxicity associated with the dietary supplement OxyELITE Pro™ — Hawaii, 2013. Drug Test Anal. 2016;8(3–4):319. doi: 10.1002/dta.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Mcmillan N, Ford M. 2013 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 31st Annual Report. Clin Toxicol. 2014;52:1032. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.987397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Food and Drug Administration. [14 May 2014];MedWatch: the FDA safety information and adverse event reporting program. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [05 May 2014];Acute hepatitis and liver failure following the use of a dietary supplement intended for weight loss or muscle building. Available at: http://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00356.asp.

- 13.Park S, Viray M, Johnston D, Taylor E, Chang A, Martin C, Schier J, Lewis L, Levri K, Chatham-Stephens K. Notes from the field: acute hepatitis and liver failure following the use of a dietary supplement intended for weight loss or muscle building — May–October 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieberman HR, Stavinoha TB, McGraw SM, White A, Hadden LS, Marriott BP. Use of dietary supplements among active-duty US Army soldiers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:985. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubertone MV, Brundage JF. The Defense Medical Surveillance System and the Department of Defense Serum Repository: Glimpses of the Future of Public Health Surveillance. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1900. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.12.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Drug Administration. [12 January 2016];Stimulant Potentially Dangerous to Health, FDA Warns. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm347270.htm.

- 17.Foley S, Butlin E, Shields W, Lacey B. Experience with OxyELITE Pro and acute liver injury in active duty service members. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:3117. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klontz KC, Debeck HJ, Leblanc P, Mogen KM, Wolpert BJ, Sabo JL, Salter M, Seelman SL, Lance SE, Monahan C, Steigman DS, Gensheimer K. The role of adverse event reporting in the FDA response to a multistate outbreak of liver disease associated with a dietary supplement. Public Health Rep. 2015;130:526. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt MP, Ju C. Mechanisms of drug-induced liver injury. AAPS J. 2006;8:E48. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navarro VJ, Seeff LB. Liver injury induced by herbal complementary and alternative medicine. Clin Liver Dis. 2013;17:715. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elinav E, Pinsker G, Safadi R, Pappo O, Bromberg M, Anis E, Keinan-Boker L, Broide E, Ackerman Z, Kaluski DN, Lev B, Shouval D. Association between consumption of Herbalife® nutritional supplements and acute hepatotoxicity. J Hepatol. 2007;47:514. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fong TL, Klontz KC, Canas-Coto A, Casper SJ, Durazo FA, Davern TJ, 2nd, Hayashi P, Lee WM, Seeff LB. Hepatotoxicity due to Hydroxycut: a case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1561. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adachi M, Saito H, Kobayashi H, Horie Y, Kato S, Yoshioka M, Ishii H. Hepatic injury in 12 patients taking the herbal weight loss aids Chaso or Onshido. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:488. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-6-200309160-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Favreau JT, Ryu ML, Braunstein G, Orshansky G, Park SS, Coody GL, Love LA, Fong TL. Severe hepatotoxicity associated with the dietary supplement LipoKinetix. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:590. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-8-200204160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM. Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Drug-induced acute liver failure: results of a U.S. multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2010;52:2065. doi: 10.1002/hep.23937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humes K, Jones N, Ramirez R. Overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy J. Herb and supplement use in the US adult population. Clin Ther. 2005;27:1847. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fontana RJ, Hayashi PH, Gu J, Reddy KR, Barnhart H, Watkins PB, Serrano J, Lee WM, Chalasani N, Stolz A, Davern T, Talwakar JA DILIN Network. Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality within 6 months from onset. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:96. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leung PS, Rossaro L, Davis PA, Park O, Tanaka A, Kikuchi K, Miyakawa H, Norman GL, Lee W, Gershwin ME Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Antimitochondrial antibodies in acute liver failure: implications for primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:1436. doi: 10.1002/hep.21828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institute of Medicine. Forging a Poison Prevention and Control System. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institutes of Health. [19 June 2014];Severity grading in drug-induced liver injury. Available at: http://livertox.nih.gov/Severity.html.

- 32.Wu CH, Wang CC, Kennedy J. Changes in herb and dietary supplement use in the US adult population: A comparison of the 2002 and 2007 National Health Interview Surveys. Clin Ther. 2011;33:1749. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]