Abstract

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) signaling is critical for proper craniofacial development. A gain-of-function mutation in the 2c splice variant of the receptor’s gene is associated with Crouzon syndrome, which is characterized by craniosynostosis, the premature fusion of one or more of the cranial vault sutures, leading to craniofacial maldevelopment. Insight into the molecular mechanism of craniosynostosis has identified the ERK-MAPK signaling cascade as a critical regulator of suture patency. The aim of this study is to investigate the role of FGFR2c-induced ERK-MAPK activation in the regulation of coronal suture development. Loss-of-function and gain-of-function Fgfr2c mutant mice have overlapping phenotypes, including coronal synostosis and craniofacial dysmorphia. In vivo analysis of coronal sutures in loss-of-function and gain-of-function models demonstrated fundamentally different pathogenesis underlying coronal suture synostosis. Calvarial osteoblasts from gain-of-function mice demonstrated enhanced osteoblastic function and maturation with concomitant increase in ERK-MAPK activation. In vitro inhibition with the ERK protein inhibitor U0126 mitigated ERK protein activation levels with a concomitant reduction in alkaline phosphatase activity. This study identifies FGFR2c-mediated ERK-MAPK signaling as a key mediator of craniofacial growth and coronal suture development. Furthermore, our results solve the apparent paradox between loss-of-function and gain-of-function FGFR2c mutants with respect to coronal suture synostosis.

Introduction

The bones of the cranial vault form by intramembranous ossification at growth sites known as sutures, which also facilitate expansion of the growing neural tissues during development. Once growth is complete, the cranial sutures fuse. Premature fusion of these sutures—a condition called craniosynostosis—disrupts the proper development of the brain and craniofacial skeleton.(Opperman, 2000) Both genome-wide association studies in humans and mouse models of skeletal development suggest that craniosynostosis results from dysregulation of multiple signaling pathways, including fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling.(Eswarakumar et al., 2005; Muenke and Schell, 1995)

FGFs are key regulators of cellular proliferation and differentiation. These processes are coordinated through a series of interactions with a family of FGF receptors (FGFRs), which include four highly conserved transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinases (FGFR1 through FGFR4).(Johnson and Williams, 1993) FGFR1 through FGFR3 demonstrate ligand-binding specificity as a consequence of alternative splicing of the immunoglobulin-like extracellular domain III, resulting in the production of IIIb and IIIc tissue-specific isoforms of each receptor.(Johnson and Williams, 1993) FGFR-mediated signaling is initiated via ligand-specific binding to the FGFR, triggering receptor homodimerization, with subsequent activation of a series of downstream pathways, including the classic phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascades.(Eswarakumar et al., 2005)

Dysregulated FGFR2 signaling has been implicated in a number of syndromic and nonsyndromic craniosynostotic conditions.(Eswarakumar et al., 2005; Muenke and Schell, 1995) Crouzon syndrome is the most common syndromic craniofacial anomaly associated with craniosynostosis and is estimated to be responsible for 4.8% of craniosynostosis cases.(Cohen and Kreiborg, 1992) Crouzon syndrome, which is characterized by coronal synostosis, maxillary hypoplasia, exorbitism, and malocclusion (Cunningham et al., 2007), results from a host of autosomal dominant gain-of-function mutations in the functional domain of the Fgfr2 gene.(Reardon et al., 1994) Currently, surgical intervention remains the mainstay of treatment.

Introduction of the most common mutation in Crouzon syndrome patients (a missense mutation at Cys342 within exon 9 of the fgfr2-IIIc gene; Fgfr2cC342Y) in mice results in a ligand-independent, constitutively activated receptor that recapitulates the features of the syndrome, including coronal synostosis.(Eswarakumar et al., 2004) Paradoxically, loss of FGFR2c signaling in mice (Fgfr2c−/−) also results in coronal synostosis.(Eswarakumar et al., 2002)

Here, we examined the effect of dysregulated FGFR2c signaling on coronal suture synostosis. Investigation of Fgfr2c mutant mice revealed that increased FGFR2c signaling correlates with ERK-MAPK pathway hyperactivation and osteoblast function as shown using a mouse model of Apert syndrome and craniosynostosis (Wang et al., 2010); these effects were reversed following pharmacological inhibition of ERK activation. Our results illustrate a novel pathogenic difference between loss-of-function and gain-of-function mice in craniosynostosis and highlight the importance of balanced signaling of growth factor pathways in the proliferation and differentiation of osteogenic suture mesenchyme.

Experimental Procedures

Animal husbandry and genetic crossing

All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines established by the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC Protocol #10449). Wild-type mice (WT), Fgfr2c-null mice (Fgfr2c−/−), Crouzon-like mice (Fgfr2cC342Y/+) were maintained on a CD-1 background. Heterozygous Fgfr2cC342Y/+ and Fgfr2cnull/+ mice were intercrossed to produce WT, Fgfr2cC342Y/+, and Fgfr2cC342Y/C342Y litters and WT and Fgfr2c−/− littermates for all experiments. For experiments involving embryonic tissues, embryonic dates were determined using the vaginal plug dating method. Genotyping was performed by PCR analysis using genomic DNA from all mice and embryos.

Micro-computed tomography (microCT), skull preparations, and morphometric analysis

Three-month-old mouse skulls were harvested and fixed in 70% ethanol overnight. MicroCT was performed (μCT40; Scanco, Bruttisellen, Switzerland) and reconstructed into a 1024 × 1024 × N image array of isometric 16-micron voxels. Three-dimensional images and two-dimensional grayscale sagittal views of the coronal suture were visually inspected to determine suture patency. Skull preparations were prepared by first stripping the specimen of all soft tissue, followed by overnight digestion in 2% KOH and staining in 0.01% Alizarin Red S (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 1% KOH for 12 hours. Standardized photographs were obtained, and morphometric analyses were performed using the US National Institutes of Health software program ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). Measurements taken included: length (distance between the anterior-most aspect of the nasal bone and posterior-most aspect of the occipital bone), width (distance between the lateral-most aspect of the parietal and interparietal sutures), inter-orbital width (distance between the frontomaxillary sutures/notches), height (distance from a line along the maxillary arch to the coronal-parietal-posterior interfrontal suture junction), and frontal height (Nakamura et al., 2009b) (distance from a straight line at the level of the posterior interfrontal-frontonasal-coronal suture junction and coronal-parietal-posterior interfrontal suture junction). Indices calculated included skull length to width, inter-orbital width:skull width ratio, skull heightskull length ratio, and frontal height:skull height ratio.

Histochemical staining

Calvaria were harvested and fixed in 70% ethanol overnight and embedded in methylmethacrylate (Sigma-Aldrich), deplastified, sectioned at 5-μm thickness, and stained with von Kossa and Goldner’s trichrome as described previously.(Kacena et al., 2004)

Calvarial osteoblast culture

E18.5 to post-natal day 1 (P1) calvaria were harvested by microdissection, washed in 4 mM EDTA/PBS, and treated with a digestion buffer containing 200 U/mL collagenase and 1.7 μg/ml Nα-Tosyl-L-Lys Chloromethyl Ketone (EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Digested calvarial tissue was filtered through a sterile 200–297 μm polypropylene mesh filter (Spectrum Labs; Rancho Dominguez, CA). Cells were collected, washed in PBS, and counted using a hemocytometer with Trypan Blue dye exclusion and cultured in α-MEM containing FBS, glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin (all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Half of the media was replaced on day 4 post-plating; cells were washed with PBS and the media was replaced on day 7, which was repeated biweekly thereafter. For alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity analysis, isolated calvarial cells were plated at a density of 2×105 cells/well in a 12-well plate and cultured in osteogenic media containing α-MEM, FBS, glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin, and 50 μg/ml ascorbate (Sigma-Aldrich). On day 11, cells were washed and stained for ALP activity using the Alkaline Phosphatase Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and inspected microscopically. To quantify ALP enzyme levels, cell protein extracts were prepared; ALP activity was assessed using the SensoLyte pNPP Alkaline Phosphatase Assay Kit (AnaSpec, Freemont, CA), and the absorbance was measured at 405 nm; results were reported as ALP concentration divided by total protein concentration. For mineralization analysis, β-glycerophosphate (10 mM) was added to cultured cells on day 7 post-plating. On day 21, cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 70% EtOH, stained with 40 mM alizarin red solution in ddH2O (pH 4.2), and washed in ddH2O. For quantification, photomicrographs of each stained well were obtained and converted to binary images and quantified using the ImageJ particle analysis function. For ALP and mineralization assays, samples were analyzed as individual wells (3–6 wells were analyzed/group), and the results were averaged from a minimum of two independent experiments. For ERK inhibition experiments, the MEK inhibitor U1026 (Favata et al., 1998) (25 μM, Promega, Madison, WI) or vehicle (control) was administered to osteoblasts every three days until the experimental endpoint.

Immunoblotting

Cellular protein extracts were prepared from cultured E18.5–P1 calvarial osteoblasts as described above or from micro-dissected coronal suture mesenchyme with overlying and underlying parietal and frontal bones; care was taken to include the least amount of nonmesenchymal tissue possible. In brief, samples were washed in PBS and incubated in modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 1% NP-40; 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; 0.1% SDS; 150 mM NaCl; 2 mM EDTA; 1 mM DTT; and 50 mM NaF; Sigma) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche; Basel, Switzerland). Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected for analysis. Protein concentration was determined using the micro-BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and immunoblotting was performed as described previously using anti-ERK and anti-phospho-ERK (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) antibodies. Densitometry was performed using ImageJ; results were expressed as a ratio of phospho-ERK:total-ERK and compared to WT levels (set at unity).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (Version 14.0.0, Microsoft Office 2011, Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and SPSS Statistics (Version 19, IBM, Armonk, NY). Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). A two-tailed student’s t test was used to compare two groups and an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test with post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test was used to compare three or more groups. Differences with a P-value of ≤0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Supplemental Methods

BM-derived osteoblast and osteoclast isolation and cell culture

Tibias and femurs were harvested from three-week-old mice, and the bone marrow was flushed in PBS containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for six minutes. Cells were collected, washed in PBS, and counted with a hemocytometer using Trypan Blue (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) dye exclusion.

For osteoclast differentiation and culturing, isolated cells were plated in a 48-well plate at a density of 1×105 cells/well. Three days after plating, M-CSF and RANKL (StemConn, New Haven, CT) were added at 30 and 50 ng/ml of media, respectively, and cells were stained for TRAP activity on day nine after plating using the Leukocyte Acid Phosphatase kit (Sigma-Aldrich). For quantification, the total number of osteoclasts was counted in each well.

To induce osteoblast differentiation, isolated cells were plated in a 24-well plate at 3×105 cells/well and cultured in osteogenic media containing α-MEM, FBS, glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin (all from Gibco), and 50 μ g/ml ascorbate (Sigma-Aldrich). On day 11 post-plating, cells were stained for ALP activity. For quantification, ≥5 images (using a 4× objective) from each stained well were converted to binary images and quantified using ImageJ. For both assays, samples were analyzed as individual wells (3–6 wells/group), and the results were averaged from a minimum of two independent experiments.

Results

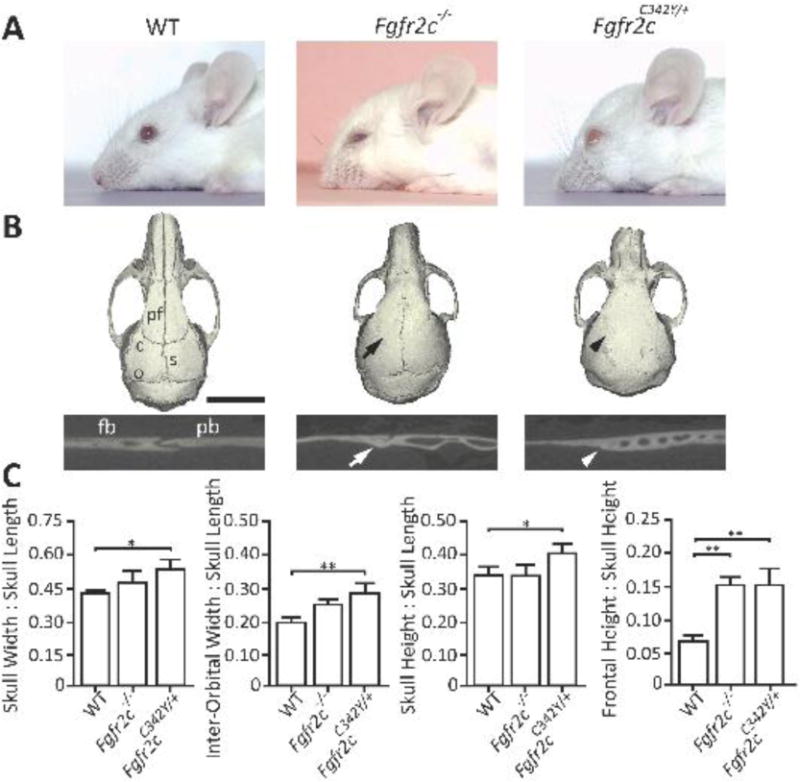

Loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations in Fgfr2c result in craniosynostosis and similar craniofacial dysmorphia

At three months of age, Fgfr2c−/− and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice present with a domed-shaped skull, retruded midface, and exorbitism (Fig. 1A). MicroCT imaging revealed patent coronal sutures in WT mice and coronal synostosis in both mutant mice; however, Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice presented with pan-synostosis of the posterior interfrontal and sagittal sutures, whereas the degree of suture involvement varied in the Fgfr2c−/− (Fig. 1B). Morphometric analysis of the craniofacial skeleton of three-month-old mice revealed that Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice presented with a more severe craniofacial dysmorphia compared to both Fgfr2c−/− and WT mice (Fig. 1C). Of note, Fgfr2c+/− mice were unaffected, with normal suture patency (data not shown).

Figure 1. Effects of loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations in Fgfr2c on coronal suture patency and craniofacial development.

A) Representative photographs of 3-month-old WT, Fgfr2c−/−, and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice. Both Fgfr2c−/− and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice present with dome-shaped skulls and a retruded midface. Ocular proptosis is also present in Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice. B) Representative microCT images reveal patent sutures in WT mice and fusion of the coronal sutures in Fgfr2c−/− (black arrow) and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice (black arrowhead), with additional sutures fused in the Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice. 2D cross-sectional images of the coronal suture demonstrate fusion in Fgfr2c−/− (white arrow) and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice (white arrowhead). C) Morphometric analysis of 3-month-old mouse skulls demonstrates more severe dysmorphia in Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice compared to Fgfr2c−/− and WT controls. Fgfr2c−/− differed from WT controls with respect to the frontal height:skull height ratio; no difference was detected between Fgfr2c−/− and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice (WT, Fgfr2c−/−, and Fgfr2cC342Y/+: n = 5, 7, and 9 mice, respectively). c, coronal suture; s, sagittal suture; pf, posterior interfrontal suture; and o, occipital suture; fb, frontal bone; pb, parietal bone. *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01. Scale bars: 3 mm (A) and 5 mm (C).

Evaluation of craniofacial skeletal and suture development reveals discrete features and altered ERK-MAPK protein levels in loss-of-function and gain-of-function Fgfr2c mutants

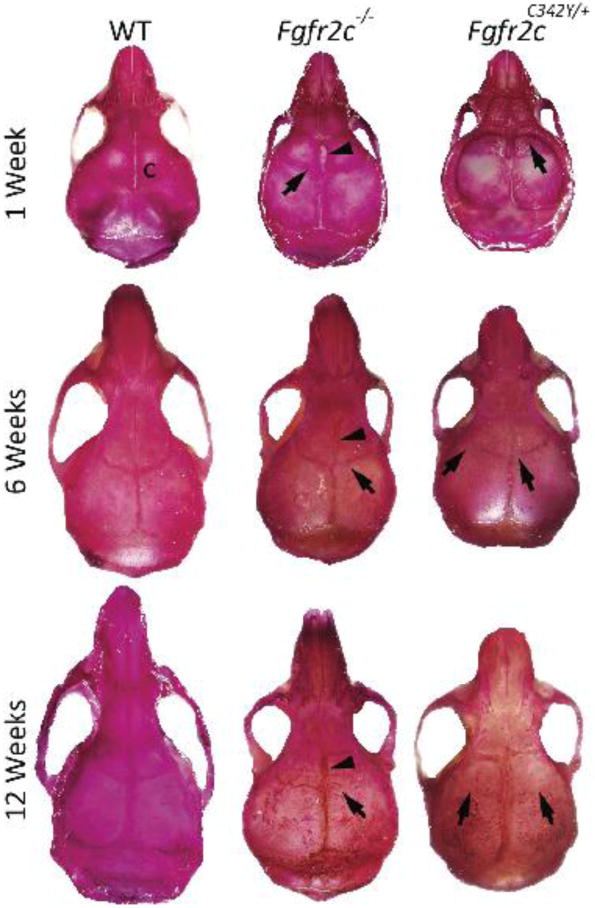

Whole-skull preparations at 1, 6, and 12 weeks of age revealed various degrees of suture patency in Fgfr2c−/− mice at 1 week, with near complete closure by 12 weeks of age. In contrast, Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice had near complete closure of the coronal suture at all ages, including 1week of age (Fig. 2). Interestingly, compared to both WT and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice, Fgfr2c−/− mice exhibited a persistently patent anterior fontanel at 1, 6, and 12 weeks of age (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Effects of loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations in Fgfr2c on craniofacial skeletal growth.

Alizarin red‒stained WT, Fgfr2c−/−, and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mouse skulls at 1, 6, and 12 weeks of age. The Fgfr2c−/− and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice have fusion of the coronal sutures (arrows) at 1 week, with near complete fusion by 6 and 12 weeks. Note the patent anterior fontanel in Fgfr2c−/− mice (n=3 mice/group/time point). c, coronal suture.

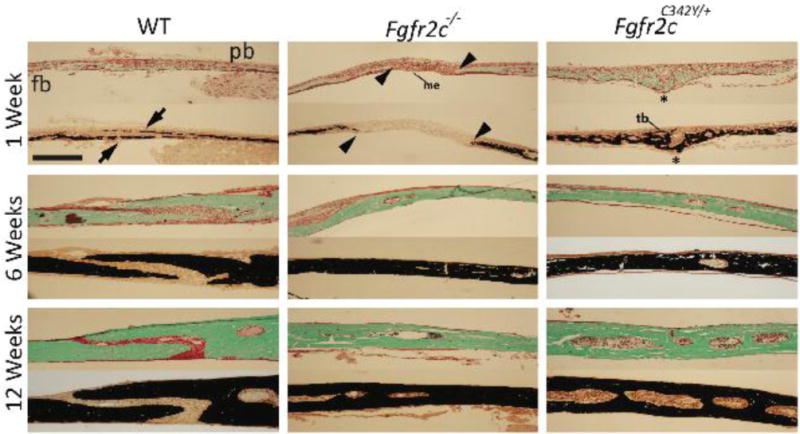

Histological evaluation of the coronal suture at 1, 6, and 12 weeks of age revealed increased mineralization and accelerated fusion of the coronal suture in Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice compared to Fgfr2c−/− and WT mice (Fig. 3). The coronal suture of Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice fused by 1 week of age, whereas Fgfr2c−/− mouse sutures fused by 6 weeks of age. In Fgfr2c−/− mice, the boney plates (frontal and parietal) showed no overlap, with wide spacing of the leading edge of the boney plates (osteogenic fronts) and less cellularity within the suture mesenchyme at 1 week of age compared to WT sutures. In contrast, trabeculae were present in the suture mesenchyme at 1 week of age in Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice. An analysis of Goldner’s trichrome and von Kossa staining revealed a delay in ossification of the osteogenic fronts in the Fgfr2c−/− mice (Fig 3).

Figure 3. Coronal suture development in loss-of-function and gain-of-function Fgfr2c mice.

Representative Goldner’s trichrome (top) and von Kossa (bottom) stained histological sections of the coronal suture in WT, Fgfr2c−/−, and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice at 1, 6, and 12 weeks of age. At 1 week, WT mice show normal overlap of the frontal and parietal bones (arrows). Fgfr2c−/− mice have reduced cellular proliferation within the suture mesenchyme, with wide spacing between the osteogenic fronts of the frontal and parietal bones (arrowheads); Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice have increased proliferation and mineralization of the mesenchyme, with trabeculae formation and suture fusion (asterisks). At 6 weeks of age, the coronal sutures in the Fgfr2c−/− and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice are completely fused (n=3 mice/group/time point). fb, frontal bone; pb, parietal bone; me, mesenchyme; tb, trabeculae. Scale bar: 50 μm for all images (10× objective for all images).

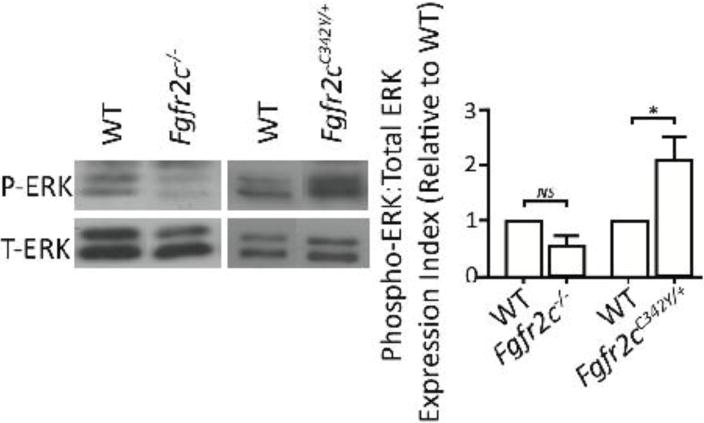

Evaluation of the coronal sutures in vivo revealed no change in the expression index of phosphorylated ERK versus total ERK in Fgfr2c−/− mice and an increased expression index in Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice compared to their respective WT controls (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. In vivo ERK-MAPK activation within the coronal suture of loss-of-function and gain-of-function Fgfr2c mice.

Representative immunoblot and densitometric analysis of phospho-ERK and total-ERK levels within the coronal sutures of E18.5 through P1 Fgfr2c−/− and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice. The sutures in the Fgfr2c−/− mice have decreased levels of phospho-ERK (relative to total-ERK) compared to WT controls, whereas Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice have significantly increased levels of phospho-ERK:total-ERK (n=4–5/group).

Calvarial osteoblast function is altered in loss-of-function and gain-of-function Fgfr2c osteoblasts and is regulated by ERK-MAPK signaling

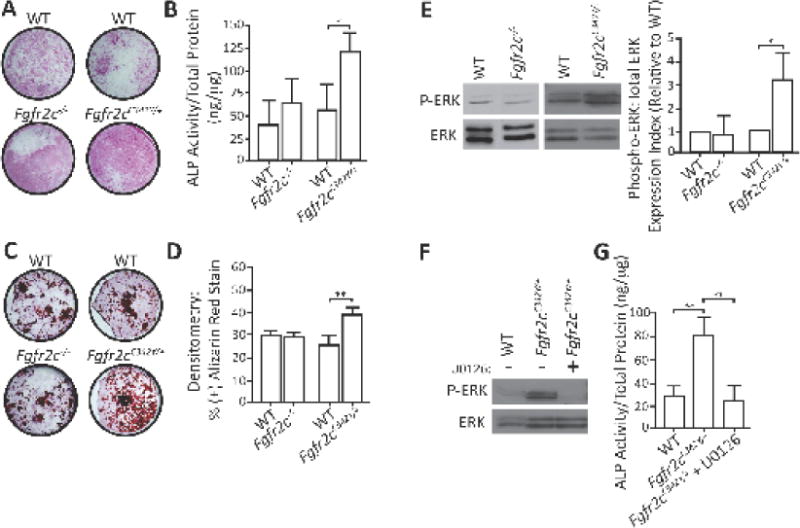

Cultured calvarial osteoblasts from Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mutants had increased ALP staining and enzymatic activity compared to WT calvarial osteoblasts (Fig. 5A and B, respectively). A similar degree of mineralized matrix was observed in Fgfr2c−/− mutants, with more mineralized matrix in the Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mutants compared to their respective WT controls (Fig. 5C and D). The osteogenic capacity of BM-derived progenitor cells to differentiate into osteoblasts or osteoclasts did not differ between WT and Fgfr2c−/− or Fgfr2cC342Y/+ BM-derived osteoblasts (Supplemental Fig. 1A and B) or osteoclasts (Supplemental Fig. 1C and D).

Figure 5. Calvarial osteoblast function and ERK-MAPK activation in loss-of-function and gain-of-function Fgfr2c mice.

A) ALP-stained WT, Fgfr2c−/−, and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ calvarial osteoblasts revealed increased ALP staining in Fgfr2cC342Y/+ osteoblasts compared to WT cells, but no significant difference between WT and Fgfr2c−/− cells. B) ALP activity was significantly higher in Fgfr2cC342Y/+ cells compared to WT controls, with no difference between WT and Fgfr2c−/− cells. C and D) Similarly, Fgfr2cC342Y/+ cells have significantly increased mineralized matrix production, whereas Fgfr2c−/− osteoblasts did not difference from WT cells (results from two independent experiments). E) Immunoblot and densitometric analyses of osteoblasts revealed increased ERK phosphorylation in Fgfr2cC342Y/+ cells compared to WT controls, but no difference between WT and Fgfr2c−/− osteoblasts. F) ALP activity was significantly lower in U0126-treated Fgfr2cC342Y/+ osteoblasts compared to WT cells. *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01.

Analysis of Fgfr2cC342Y/+ osteoblasts revealed an increased phospho-ERK:total-ERK ratio compared to WT cells; no difference in phospho-ERK was observed in Fgfr2c−/− osteoblasts (Fig. 5E). In a separate set of experiments, administration of the MEK inhibitor U0126—which prevents phosphorylation of ERK (and thus its activation) (Favata et al., 1998)—to Fgfr2cC342Y/+ osteoblasts reduced ALP enzymatic activity (Fig. 5F).

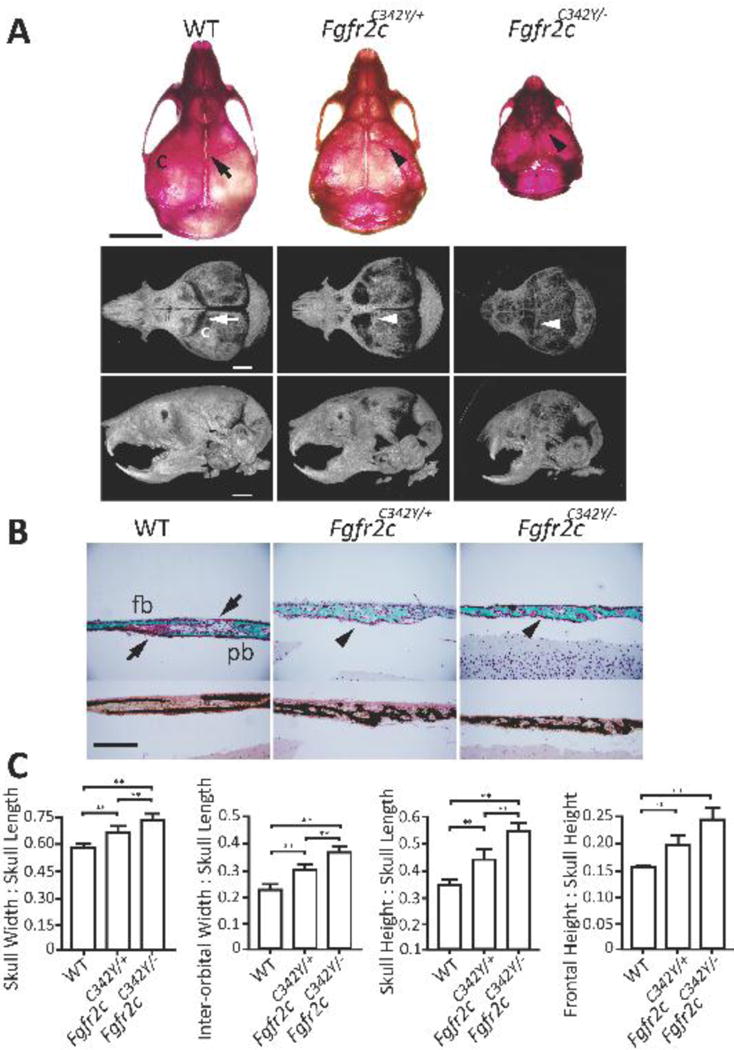

Loss of WT allele in the gain-of-function hemizygotes results in severe craniofacial defects and growth retardation

To investigate the role of the FGFR2c C342Y mutant receptor in the absence of a WT receptor, we generated hemizygous Fgfr2cC342Y/− mutant mice by intercrossing Fgfr2c+/− with Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice. Of the resulting four genotypes, the WT and Fgfr2c+/− mice are indistinguishable from each other, with no obvious craniofacial or growth defects. On the other hand, the growth of hemizygous Fgfr2cC342Y/− mutant mice is severely stunted, with significantly smaller body weight compared to the WT or Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mutant mice; these mice do not survive beyond 11 days of age (Supplemental Figure 2).

Alizarin red and microCT analysis showed that both mutant mouse lines have fused coronal sutures. In addition, we observed severe truncation of the facial bones in the hemizygous mutants (Fig 6 A lower panel; lateral view), resulting in class III malocclusion. Histological analysis of the coronal sutures revealed complete fusion in both mutant mouse lines (Fig 6B). Finally, morphometric analyses of the skull revealed severe defects in the hemizygous mutants and significantly higher ratios compared to both the heterozygous mutant mice and WT mice (Fig 6C).

Figure 6. Effects of heterozygous gain-of-function mutations in combination of the loss of the WT Fgfr2c allele on coronal suture patency and craniofacial development.

A) Representative alizarin red (top, dorsal view) and microCT (bottom; dorsal and lateral views) images reveal patent sutures in 10-day-old WT mice (arrow) and fused coronal sutures in Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice and Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice (arrowheads). Note the severe midface retrusion with resulting class III malocclusion and a domed-shaped skull in the Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice (bottom; lateral view). B) Representative Goldner’s trichrome (top) and von Kossa (bottom) stained histological sections of the coronal suture of 10-day-old WT, Fgfr2cC342Y/+, and Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice show normal overlap of the frontal and parietal bones (arrows); Fgfr2cC342Y/+ and Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice have advanced trabecule formation and coronal suture fusion (arrowheads). C) Morphometric analysis of 10-day-old mouse skulls revealed more severe dysmorphia in the Fgfr2cC342Y/+ (n=12 mice) and Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice (n=7 mice) compared to WT controls (n=5 mice). c, coronal suture; fb, frontal bone; pb, parietal bone. **P≤0.01. Scale bars: 5 mm (A, top), 2 mm (A, bottom; lateral), and 200 μm (B); 20× objective (B).

Discussion

The bones of the calvarium form by intramembranous ossification, a process that is driven by the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal cells into osteoid matrix-secreting osteoblasts. Calvarial bones grow in specialized fibrous joints called sutures. Maintenance of cranial suture patency during development is a dynamic process coordinated through the communication of multiple cell types and signaling pathways. Dysregulation of suture patency can lead to craniosynostosis, a common congenital disorder that affects 1 in 2500 live births (Wilkie, 1997) and can result in growth aberrations in the cranial vault and base, as well as the underlying neural tissues. Here, we investigated the cellular and molecular pathways regulating premature suture fusion and craniofacial growth in the context of dysregulated FGFR2c signaling using loss-of-function and gain-of-function mouse models.

The coronal suture is part of the boundary between neural crest cell-derived structures (i.e., the viscerocranium, which includes the frontal and facial bones) and paraxial mesoderm‒derived structures (i.e., the neurocranium, which includes the parietal bones and the remaining bones of the cranial vault). Moreover, in contrast to other cranial sutures, which are formed by the direct apposition of osteogenic fronts on a level plane, the coronal suture is formed by the overlapping osteogenic fronts of the frontal and parietal bones early in development. It is important to note that the coronal suture never fuses in mice. However, our evaluation of the loss-of-function and gain-of-function Fgfr2c mutants revealed that coronal suture synostosis occurs by two contrasting mechanisms (Fig. 3). In one-week-old Fgfr2c−/− mice, the frontal and parietal osteogenic fronts do not overlap, but remained separated, delaying mineralization of the osteogenic fronts. On the other hand, at this age in the Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice, mineralized trabecular bones in the suture mesenchyme connect the frontal and parietal bones. Surprisingly, by six weeks of age, the coronal sutures in both Fgfr2c−/− and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice were completely fused and were nearly indistinguishable from each other. To explain this seemingly contradictory observation, Iseki et al. proposed that the development and patency of the coronal suture is a dynamic process regulated by FGFR1 and FGFR2, which play contrasting roles by positively regulating osteoblast differentiation and proliferation, respectively.(Iseki et al., 1999) Under normal conditions, increased FGF stimulation down-regulates FGFR2 and upregulates FGFR1 to induce osteoblast differentiation. Consistent with this hypothesis, our previous analysis of Fgfr2c−/− mice revealed decreased osteoblast proliferation within the coronal suture mesenchyme (Eswarakumar et al., 2002), whereas Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice exhibited a hyperproliferative phenotype.(Eswarakumar et al., 2004) Similarly, Holmes et al. examined a mouse model of Apert syndrome that arises from a separate gain-of-function mutation in Fgfr2 and found that mutant osteoblasts within the suture mesenchyme have enhanced proliferative capacity followed by early differentiation, ultimately leading to suture ossification (Holmes et al., 2009). Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that the loss of FGFR2c signaling may have shifted the balance between proliferation and differentiation in favor of differentiation, thereby leading to the slow but eventual fusion of coronal sutures in Fgfr2c−/− mice.

The ERK-MAPK signaling pathway is a key regulator of cellular proliferation and differentiation. In the context of osteogenesis, ERK-MAPK signaling is required for proper osteoblast function and differentiation and has been shown to regulate craniofacial growth and suture patency.(Nakamura et al., 2009a; Shukla et al., 2007) Supporting these findings, calvarial osteoblasts obtained from Fgfr2cC342Y/+ have increased phospho-ERK levels; however, no change in phospho-ERK levels was detected in Fgfr2c−/− osteoblasts. In addition, inhibition of ERK-MAPK signaling in Fgfr2cC342Y/+ cells effectively decreased osteoblast activity. Consistent with these findings, previous studies found that craniofacial dysmorphia and craniosynostosis were prevented by administration of the MEK inhibitor U0126.(Nakamura et al., 2009a; Shukla et al., 2007) Together, these findings suggest that the enhanced osteoblast activity and differentiation observed in Fgfr2cC342Y/+ osteoblasts may be directly related to hyperactivation of ERK-MAPK signaling.

Neural crest cell‒derived tissues may be more susceptible to mutations that affect FGFR function compared to mesoderm-derived tissues. The mammalian skull vault is comprised of two migratory mesenchymal cell populations—the cranial neural crest and the paraxial mesoderm. The nasal, frontal, sphenoid, and temporal bones are created from cranial neural crest-derived osteoblasts, whereas the parietal and occipital bones are created from paraxial mesoderm-derived osteoblasts (Jiang et al., 2002). Our analysis of Fgfr2cC342Y/+ skulls at one, two, and three weeks of age revealed that the sutures surrounded by the nasal, frontal, sphenoid, and temporal bones are prematurely fused (Supplementary Fig. 3), whereas the sutures between the parietal and occipital bones remain patent. This suggests that neural crest osteoblasts may contain specific transcription factors and/or targets that are more susceptible to changes in FGFR2 signaling. Similarly, Liu et al. reported that Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice have reduced frontal bone volume compared to parietal bone volume, and calvarial cells obtained from the frontal bone of 4-week-old Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice have enhanced early osteoblasts (Liu et al., 2013). Because craniosynostosis occurs in heterozygous patients with Crouzon syndrome, a number of questions arise regarding the pathogenesis: Is FGFR2c function required for synostosis to occur, or is the mutant receptor sufficient to induce synostosis? Thus, does the presence—or absence—of WT FGFR2c affect the phenotype? To address these questions, we generated hemizygous Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice, which lack the WT allele. A detailed analysis of this animal’s craniofacial defects revealed that in the absence of a WT Fgfr2c allele, the phenotype becomes severe in all aspects measured. Specifically, although the skulls of heterozygous Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice are proportionately wider and taller than WT mice, these differences are even more pronounced in hemizygous Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice. This key finding suggests that the severity of the pathogenic signal is exacerbated in the absence of the WT allele, suggesting that the WT allele may play a protective role in patients. Notably, the facial bones derived from the neural crest are the most affected skull bones in the hemizygous Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice, further supporting the notion that neural crest‒derived osteoblasts are highly sensitive to FGFR2c signaling.

Conclusions

Here, we report several key findings. First, loss-of-function and gain-of-function Fgfr2c mutations result in coronal suture synostosis via two distinct mechanisms. Second, Loss of FGFR2c signaling results in reduced cellularity and growth of osteogenic fronts, leading to delayed fusion of the coronal suture. Third, the increased cellularity and dysregulated differentiation of osteoblasts in the coronal suture are caused by gain-of-function mutations in FGFR2c, leading to premature fusion. Fourth, hemizygosity of the FGFR2cC342Y allele causes severe craniofacial defects in neural crest‒derived facial bones. Fifth, increased levels of phospho-ERK1/2 levels are present in the coronal sutures and primary osteoblasts of gain-of-function—but not loss-of-function—mutants. Finally, inhibition of calvarial osteoblast ERK1/2 activation restores osteoblast ALP activity to WT levels. Taken together, these results demonstrate that ERK-MAPK signaling is a key mediator of hyperactivated FGFR2c signaling and may contribute to both craniosynostosis and craniofacial growth aberrations, presumably via an osteoblast-dependent mechanism.

Supplementary Material

A) Representative photomicrograph of ALP-stained BM-derived osteoblasts from Fgfr2c−/− and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice reveal no obvious difference in ALP staining. B) Quantification of staining confirms no difference between the groups. C and D) No apparent difference in BM-derived osteoclast activity (C) or the number of osteoclasts (D) was observed.

A) Representative photographs of 10-day-old WT, Fgfr2cC342Y/+, and Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice showing that Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice are smaller in size compared to both WT and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice. B) Total body weight was significantly reduced in 10 day-old Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice compared to both WT and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice. **P≤0.01. Scale bar: 10 mm (A).

1–3-week-old calvaria showing the fusion of sutures surrounding neural crest‒derived bones (arrows). B) Squamosal suture between the temporal and parietal bone is fused. D, F) Show the fused sphenofrontal and squamosal sutures between the sphenoid, frontal, and temporal bones. Abbreviations, S, sphenoid bone; T, temporal bone.

Highlights.

Loss and gain-of-function Fgfr2c mutations result in coronal suture synostosis.

Loss of FGFR2c signaling results in reduced cellularity and growth of osteogenic fronts.

Activating FGFR2c mutation causes increased cellularity and dysregulated differentiation.

Hemizygosity of FGFR2cC342Y allele causes severe defects in viscerocranium.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yale Core Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (YCCMD) for technical service. This work was supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIH/NIDCR) Grant DE020823 (to J.E.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure

The author and all involved parties have no commercial associations or financial disclosures that would create a conflict of interest with the information presented.

References

- Cohen MM, Jr, Kreiborg S. Birth prevalence studies of the Crouzon syndrome: comparison of direct and indirect methods. Clin Genet. 1992;41:12–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1992.tb03620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham ML, Seto ML, Ratisoontorn C, Heike CL, Hing AV. Syndromic craniosynostosis: from history to hydrogen bonds. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2007;10:67–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswarakumar VP, Horowitz MC, Locklin R, Morriss-Kay GM, Lonai P. A gain-of-function mutation of Fgfr2c demonstrates the roles of this receptor variant in osteogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12555–12560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405031101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswarakumar VP, Monsonego-Ornan E, Pines M, Antonopoulou I, Morriss-Kay GM, Lonai P. The IIIc alternative of Fgfr2 is a positive regulator of bone formation. Development. 2002;129:3783–3793. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.16.3783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favata MF, Horiuchi KY, Manos EJ, Daulerio AJ, Stradley DA, Feeser WS, Van Dyk DE, Pitts WJ, Earl RA, Hobbs F, Copeland RA, Magolda RL, Scherle PA, Trzaskos JM. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18623–18632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes G, Rothschild G, Roy UB, Deng CX, Mansukhani A, Basilico C. Early onset of craniosynostosis in an Apert mouse model reveals critical features of this pathology. Dev Biol. 2009;328:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseki S, Wilkie AO, Morriss-Kay GM. Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 have distinct differentiation- and proliferation-related roles in the developing mouse skull vault. Development. 1999;126:5611–5620. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Iseki S, Maxson RE, Sucov HM, Morriss-Kay GM. Tissue origins and interactions in the mammalian skull vault. Dev Biol. 2002;241:106–116. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE, Williams LT. Structural and functional diversity in the FGF receptor multigene family. Adv Cancer Res. 1993;60:1–41. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60821-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacena MA, Troiano NW, Coady CE, Horowitz MC. HistoChoice as an alternative to formalin fixation of undecalcified bone specimens. Biotech Histochem. 2004;79:185–190. doi: 10.1080/10520290400015506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Nam HK, Wang E, Hatch NE. Further analysis of the Crouzon mouse: effects of the FGFR2(C342Y) mutation are cranial bone-dependent. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92:451–466. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9701-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenke M, Schell U. Fibroblast-growth-factor receptor mutations in human skeletal disorders. Trends Genet. 1995;11:308–313. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Gulick J, Pratt R, Robbins J. Noonan syndrome is associated with enhanced pERK activity, the repression of which can prevent craniofacial malformations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009a;106:15436–15441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903302106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Gulick J, Pratt R, Robbins J. Noonan syndrome is associated with enhanced pERK activity, the repression of which can prevent craniofacial malformations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009b;106:15436–15441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903302106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman LA. Cranial sutures as intramembranous bone growth sites. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:472–485. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1073>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon W, Winter RM, Rutland P, Pulleyn LJ, Jones BM, Malcolm S. Mutations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 gene cause Crouzon syndrome. Nat Genet. 1994;8:98–103. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla V, Coumoul X, Wang RH, Kim HS, Deng CX. RNA interference and inhibition of MEK-ERK signaling prevent abnormal skeletal phenotypes in a mouse model of craniosynostosis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1145–1150. doi: 10.1038/ng2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Sun M, Uhlhorn VL, Zhou X, Peter I, Martinez-Abadias N, Hill CA, Percival CJ, Richtsmeier JT, Huso DL, Jabs EW. Activation of p38 MAPK pathway in the skull abnormalities of Apert syndrome Fgfr2(+P253R) mice. BMC developmental biology. 2010;10:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie AO. Craniosynostosis: genes and mechanisms. Human molecular genetics. 1997;6:1647–1656. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.10.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A) Representative photomicrograph of ALP-stained BM-derived osteoblasts from Fgfr2c−/− and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice reveal no obvious difference in ALP staining. B) Quantification of staining confirms no difference between the groups. C and D) No apparent difference in BM-derived osteoclast activity (C) or the number of osteoclasts (D) was observed.

A) Representative photographs of 10-day-old WT, Fgfr2cC342Y/+, and Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice showing that Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice are smaller in size compared to both WT and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice. B) Total body weight was significantly reduced in 10 day-old Fgfr2cC342Y/− mice compared to both WT and Fgfr2cC342Y/+ mice. **P≤0.01. Scale bar: 10 mm (A).

1–3-week-old calvaria showing the fusion of sutures surrounding neural crest‒derived bones (arrows). B) Squamosal suture between the temporal and parietal bone is fused. D, F) Show the fused sphenofrontal and squamosal sutures between the sphenoid, frontal, and temporal bones. Abbreviations, S, sphenoid bone; T, temporal bone.