Short abstract

The specific effects of non-pharmaceutical treatments are not always divisible from placebo effects and may be missed in randomised trials

The randomised double blind controlled trial has proved an invaluable tool for testing the efficacy of new drugs. However, it is now used to evaluate complex non-pharmaceutical interventions, many of which are based on different therapeutic theories. For example, randomised controlled trials are used to test physiotherapy, a complex intervention with a basis in biomedical theory, and acupuncture, which is often based on Chinese medicine. In order to use a placebo or sham controlled design, an intervention has to be divided into characteristic (specific) and incidental (placebo, non-specific) elements. However, recent research suggests that it is not meaningful to split complex interventions into characteristic and incidental elements. Elements that are categorised as incidental in drug trials may be integral to non-pharmaceutical interventions. If this is true, the use of placebo or sham controlled trial designs in evaluating complex non-pharmaceutical interventions may generate false negative results.

Figure 1.

The characteristic effects of acupuncture extend beyond needling

Credit: WELLCOME PHOTOGRAPHIC LIBRARY

Characteristic and incidental effects

A treatment, or healthcare delivery encounter,1 contains a spectrum of treatment factors and associated effects for which numerous terms and definitions are used. We will use the terms characteristic effects (specific effects) and incidental effects (placebo, non-specific, context effects) as defined by Grunbaum.2,3 Characteristic factors are therapeutic actions or strategies that are theoretically derived, unique to a specific treatment, and believed to be causally responsible for the outcome—for example, a drug. Incidental factors are the many other factors that have also been shown to affect outcome, such as the credibility of the intervention, patient expectations, the manner and consultation style of the practitioner, and the therapeutic setting.1,4 In randomised controlled designs, these incidental factors also include a dummy pill or a sham intervention. A factor that is characteristic within one therapeutic system may be incidental to another.2

Underlying assumptions of placebo controlled design

Three assumptions underlie the design of randomised controlled trials:

The diagnostic process takes place before the trial intervention begins

Incidental factors are generic and not linked to any particular therapeutic theory

Characteristic effects and incidental effects are distinct and additive.

Our clinical and research experience has led us to question whether these assumptions hold true for trials of non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as physiotherapy and acupuncture. In this paper we draw particularly on a programme of research into acupuncture and Chinese medicine5-7 (hereafter termed simply acupuncture) based on 88 interviews with patients and 11 with professional acupuncturists. This in depth study of acupuncture leads to several conclusions that can be tested in other contexts. We start by taking each of the above assumptions in turn and testing to what extent they are supported or refuted by the interview data.

Diagnosis takes place before the intervention begins

The biomedical diagnosis determines eligibility for the trial and therefore occurs before the intervention is started. In a drug trial, this biomedical diagnosis is also the theoretical basis for prescribing the drug and standardised administration of the drug follows. This is also the model that underlies prescribing in everyday practice, albeit a model that many biomedical encounters do not adhere to.

In a trial of acupuncture, however, the biomedical diagnosis that precedes the trial is not the theoretical understanding that guides treatment. The acupuncturist, through questioning and examination, will make a Chinese diagnosis during the first treatment session and will review and amend that diagnosis at each subsequent session. Thus the diagnostic process is woven into each treatment session with, for example, repeated pulse taking and feedback about the effects of needle insertion. This emergent and contingent diagnosis will not only determine the treatment at each session but is likely to have a direct effect by eliciting what Moerman terms a meaning response.8 This diagnostic process is integral to the Chinese system of medicine, and therefore, by definition, gives rise to a characteristic effect, not an incidental one. In recognition of this difficulty, it has been suggested that inclusion criteria for a trial could include both biomedical and Chinese medicine diagnoses,9 but this is difficult in practical terms and does not allow for the emergent nature of Chinese diagnoses.

Incidental factors are generic and independent of treatment effect

Although biomedicine acknowledges the importance and potential therapeutic power of factors such as the therapeutic relationship, it views their effect as separate from the characteristic effect of a drug based intervention. Consequently, aspects of the therapeutic relationship, such as talking and listening, are categorised as placebo (incidental factors) and viewed as generic elements that operate independently from any characteristic intervention that is being delivered.

However, our interview data show that this is not the case within acupuncture consultations. Although some aspects of talking and being listened to are incidental (such as focused attention and empathy), other aspects are characteristic of acupuncture and its underlying theory. For example, the way that a history is taken at the initial consultation indicates to patients that everything about them is relevant to the diagnosis and treatment plan. During subsequent treatment sessions needle insertion and healthcare advice are often varied to take into account any new concerns, whether physical, emotional, or social. This type of talking and listening may result in an increasingly participative interaction in which the whole burden of illness can be shared and partially relieved.

Discussion of central concepts of Chinese medicine, such as seeking to be in balance both within yourself and with a wider context of work and family, aims to promote increased self awareness, self confidence, and self responsibility. Some interviewees noted that this process was different from that experienced with biomedical doctors. They described, for example, how they have been socialised to take certain concerns to a doctor and not others and how doctors, especially consultants, prefer to treat one problem at a time. This difference is not a function of the individual practitioner, or the length of the consultation, but is a function of the different theoretical models underlying biomedicine and acupuncture. Studies of other treatments, such as reflexology and naturopathy, also describe different types of talking and listening that are dependent on the underlying theory.10,11

Characteristic and incidental effects are distinct and additive

This third assumption arises from the original focus of randomised controlled trials on drugs. Drugs exist as material entities in the forms of pills or injections and can therefore be physically separated from most other aspects of an intervention. In acupuncture, however, the characteristic factors include needling, aspects of the diagnostic process, and aspects of talking and listening, and we have already described how emergent and interwoven these are into the whole intervention. This third assumption has also been challenged by others.2,12,13 For example, a review of interactions between characteristic effects of medications and incidental effects concluded that “the implicit additive model of the RCT is too simple.”12 Consequently, several interactive multidimensional models have been formulated and described.14,15

Implications for trials of acupuncture

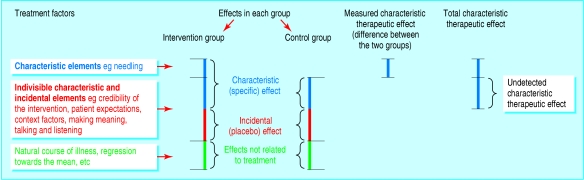

Our analysis suggests that the treatment factors that are characteristic of acupuncture include, in addition to the needling, the diagnostic process and aspects of talking and listening. Within the treatment sessions these characteristic factors are distinct but not divisible from incidental elements, such as empathy and focused attention. These findings have important consequences for the design of trials. A sham controlled acupuncture trial, the classic design for efficacy or explanatory trials, is based on the supposition that the needling alone is the characteristic treatment element. Therefore participants in the control group receive everything except the needling. If, however, other aspects of treatment are characteristic, the sham acupuncture design is inappropriate because it delivers these other characteristic elements to both groups. Consequently, the difference between the groups may greatly underestimate the total treatment effect of the intervention (figure).

Figure 2.

Application of randomised controlled design to trial of non-pharmaceutical intervention such as acupuncture

A sham controlled trial is only appropriate for comparing two acupuncture interventions—for example, to compare the effects of different needling techniques. In such a trial it is the effect of needling that is being compared rather than the total characteristic effect of the acupuncture.

Many thoughtful papers about trial design in complementary medicine have aired similar concerns.9,13,15,16 For example, members of the International Acupuncture Research Forum acknowledged that “Some effects that are included in the term `non-specific' may be peculiar to acupuncture,”17 and a scholarly overview of controlled clinical trials in acupuncture recognised: “The probable interaction of treatment effects of the different specific and non-specific effects of the treatment.”18 Nevertheless, these papers have continued to recommend using sham controlled acupuncture studies. This reticence in challenging the status quo may be because the assumptions that underlie dominant or commonly held theories such as biomedicine are invisible until they are illuminated by a body of primary research.

Our findings may also prove useful in understanding some of the many paradoxes within the literature on the placebo effect. For example, they explain two recurring paradoxes in relation to sham acupuncture trials. Firstly, the discrepancy between acupuncture's long history and widespread use and its lack of proved clinical effectiveness in randomised controlled trials and, secondly, the fact that generally both sham and real acupuncture have good treatment effects.9

Other complex interventions

Psychotherapy is another treatment that, like acupuncture, has a non-biomedical theory base. Researchers are explicitly seeking to delineate the incidental factors (termed common factors) across different types of therapeutic approach, and they have suggested that factors that are incidental to biomedicine encounters may be characteristic to psychotherapeutic ones.19

Complex interventions that are largely based on a biomedical explanatory system, such as physiotherapy, lie in a middle ground. Our experience of randomised controlled trials of complex packages of care built round physiotherapy20 suggests that all three assumptions are to be questioned in this context, albeit not so fundamentally as in the case of acupuncture. Firstly, it is the physiotherapist's assessment, rather than the biomedical diagnosis, that determines the treatment. For example, after a medical diagnosis of osteoarthritis of the knee, physiotherapists may diagnose weakness of particular muscles or ligaments and review this diagnosis at subsequent sessions. Secondly, many physiotherapists would assert that talking and listening, in terms of promoting patient education and self help, is integral to a physiotherapy intervention, even within the context of an explanatory trial. Thirdly, such flexible and participative treatment sessions are unlikely to be made up of incidental and characteristic factors that are distinct, divisible, and additive in their effects.

Summary points

The randomised placebo controlled trial was developed to test new drugs and is based on biomedical assumptions

In a drug trial, elements such as talking and listening are defined as incidental (placebo) factors and separate from the characteristic drug treatment

In acupuncture and other non-pharmaceutical therapies the characteristic and incidental factors are intertwined

Use of placebo or sham controlled trial designs for complex interventions may lead to false negative results

Conclusion

Our conclusion accords with Grunbaum's original formulation that it is the underlying therapeutic theory that determines which treatment factors should be classified as characteristic and as incidental and to what extent such elements are divisible. Many of the elements of the healthcare encounter that are categorised as incidental in the context of drug trials are integral to complex non-pharmaceutical interventions. The use of placebo or sham controlled trial designs will not therefore detect the whole characteristic effect and may generate false negative results. Consequently, other approaches, such as randomised pragmatic designs and randomised cluster designs, are more appropriate and rigorous.

We wish to thank Pamela Trevithick for her insightful comments and Jos Kleijnen for his helpful review.

Contributors and sources: CP had the idea for the article and wrote the first draft and PD discussed ideas and contributed to writing subsequent drafts. Both authors have seen and approved the final paper. CP is the guarantor. Both authors combine a lifetime of clinical experience with a keen interest in research methodology. CP has many years' experience of researching complementary therapies, especially acupuncture, and PD's extensive research into osteoarthritis has included evaluations of complex packages of care.

Funding: This work was supported by the MRC Health Services Research Collaboration.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, Hart J, Kimber A, Thomas H. The role of expectancies in the placebo effect and their use in the delivery of health care: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 1999;3(3): 1-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grunbaum A. Explication and implications of the placebo concept. In: White L, Tursky B, Schwartz GE, eds. Placebo theory, research, and mechanisms. New York: Guilford Press, 1985: 9-36.

- 3.Hrobjartsson A. What are the main methodological problems in the estimation of placebo effects? J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55: 430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Blasi Z, Harkness E, Ernst E, Georgiou A, Kleijen J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet 2001;357: 757-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paterson C, Britten N. In pursuit of patient-centred outcomes: a qualitative evaluation of MYMOP, measure yourself medical outcome profile. J Health Serv Res Policy 2000;5: 27-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paterson C, Britten N. Acupuncture for people with chronic illness: combining qualitative and quantitative outcome assessment. J Altern Complement Med 2003;5: 671-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paterson C, Britten N. Acupuncture as a complex intervention: a holistic model. J Altern Complement Med 2004;10: 791-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moerman D. Meaning, medicine and the placebo effect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- 9.Lewith G, Walach H, Jonas WB. Balanced research strategies for complementary and alternative medicine. In: Lewith G, Jonas WB, Walach H, eds. Clinical research in complementary therapies. Principles, problems and solutions. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002: 1-28.

- 10.Johannessen H. Individualized knowledge: reflexologists, biopaths and kinesiologists in Denmark. In: Cant S, Sharma U, eds. Complementary and alternative medicines: knowledge in practice. London: Free Association Books, 1996: 116-34.

- 11.Power R. Only nature heals: a discussion of therapeutic responsibility from a naturopathic point of view. In: Budd S, Sharma U, eds. The healing bond. London: Routledge, 1994: 193-213.

- 12.Kleijen J, de Craen AJM, van Everdingen J, Krol L. Placebo effect in double-blind clinical trials: a review of interactions with medications. Lancet 1994;344: 1347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barfod TS. Placebo therapy in dermatology. Clin Dermatol 1999;17: 69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bootzin RB, Caspi O. Explanatory mechanisms for placebo effects: cognition, personality and social learning. In: Guess HA, Kleinman A, Kusek JW, Engel LW, eds. The science of the placebo. Toward an interdisciplinary research agenda. London: BMJ Books, 2002: 108-32.

- 15.Kaptchuk TJ, Edwards RA, Eisenberg DM. Complementary medicine: efficacy beyond the placebo effect. In: Ernst E, ed. Complementary medicine: an objective appraisal. Oxford: Butterworth Heinmann, 1996: 31-41.

- 16.Mason S, Tovey P, Long AF. Evaluating complementary medicine: methodological challenges of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2002;325: 832-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White AR, Filshie J, Cummings TM. Clinical trials of acupuncture: consensus recommendations for optimal treatment, sham controls and blinding. Complement Ther Med 2001;9: 237-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birch S. Clinical research on acupuncture. Part 2: Controlled clinical trials, an overview of their methods. J Altern Complement Med 2004;10: 481-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grencavage LM, Norcross JC. Where are the commonalities among the therapeutic common factors? Prof Psychol Res Pract 1990;21: 372-8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quilty B, Tucker M, Campbell R, Dieppe P. Physiotherapy, including quadriceps exercises and patellar taping, for knee osteoarthritis with predominant patello-femoral joint involvement: randomised controlled trial. J Rheumatol 2003;30: 1311-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]