Abstract

Vulnerability and instability in carotid artery plaque has been assessed based on strain variations using noninvasive ultrasound imaging. We previously demonstrated that carotid plaques with higher strain indices in a region of interest (ROI) correlated to patients with lower cognition, probably due to cerebrovascular emboli arising from these unstable plaques. This work attempts to characterize the strain distribution throughout the entire plaque region instead of being restricted to a single localized ROI. Multiple ROIs are selected within the entire plaque region, based on thresholds determined by the maximum and average strains in the entire plaque, enabling generation of additional relevant strain indices. Ultrasound strain imaging of carotid plaques, was performed on 60 human patients using an 18L6 transducer coupled to a Siemens Acuson S2000 system to acquire radiofrequency data over several cardiac cycles. Patients also underwent a battery of neuropsychological tests under a protocol based on National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Canadian Stroke Network guidelines. Correlation of strain indices with composite cognitive index of executive function revealed a negative association relating high strain to poor cognition. Patients grouped into high and low cognition groups were then classified using these additional strain indices. One of our newer indices, namely the average L-1 norm with plaque (AL1NWP) presented with significantly improved correlation with executive function when compared to our previously reported maximum accumulated strain indices (MASI). An optimal combination of three of the new indices generated classifiers of patient cognition with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.880, 0.921 and 0.905 for all (n=60), symptomatic (n=33) and asymptomatic patients (n=27) whereas classifiers using maximum accumulated strain indices alone provided AUC values of 0.817, 0.815 and 0.813 respectively.

Keywords: Elastography, elasticity imaging, strain imaging, carotid plaque, vascular cognitive impairment, ultrasound

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is the leading cause of arterial disease, with the carotid artery bifurcation being one of the symptomatically sensitive areas for plaque deposition (Glagov et al., 1988). Emboli arising from unstable carotid artery plaque can flow into the brain vasculature and result in ischemic events, cognitive impairment or both (Whisnant et al., 1990). Plaque instability is influenced by the composition of the plaque and mechanical properties of the arterial wall (Stary, 1992; Stary et al., 1995). However, clinical management is largely determined by the percent stenosis as derived from medical imaging tests (Dempsey et al., 2010; Brott et al., 2011; NASCET, 1999) and therefore does not include comprehensive evaluation of the composition and mechanical properties associated with plaque instability. Our research utilizes structurally-based, noninvasive strain indices as vascular biomarkers for early diagnosis of vascular sites in the carotid at risk for embolization due to unstable plaque (Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2015; Berman et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2014; Rocque et al., 2012; Dempsey et al., 2010).

Ultrasound strain estimates map the mechanical deformation of tissues to identify tissue stiffness changes (Ophir et al., 1991; Varghese, 2009). Strain imaging has been used in the assessment of unstable carotid artery plaque based on axial, lateral and shear strain variations over a cardiac cycle (Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2014; McCormick et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2008). Other groups have also proposed metrics based on strain to assess plaque instability (Widman et al., 2015; Majdouline et al., 2014; Ribbers et al., 2007). Hansen et al. (Hansen et al., 2016) used compound ultrasound strain imaging to calculate radial strain in the transverse plane. They used the 50th strain percentile and percentage of the area above 0.5% strain to classify fibrous and (fibro) atheromatous plaque. Huang et al. (Huang et al., 2016a) used the axial strain rate at locations with high echogenicity and signal to noise ratio to classify stable and unstable plaque using a double-blinded magnetic resonance imaging review for the ground truth. Vessel phantoms have also been utilized by some groups to develop strain algorithms (Hansen et al., 2014; Korukonda et al., 2013; Hasegawa and Kanai, 2008). Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging has been used (Czernuszewicz et al., 2015; Doherty et al., 2015) to estimate displacements in carotid plaque.

Recently, shear wave elastography has been applied to generate quantitative characteristics using shear modulus maps for assessing unstable plaque (Garrard et al., 2015; Ramnarine et al., 2014). Li et al. (Li et al., 2016) measured the shear modulus to characterize arterial stiffness in the common carotid for patients diagnosed with an acute ischemic stroke and found it to be elevated when compared to age and sex matched controls. Widman et al. (Widman et al., 2016) also used shear wave elastography to calculate the shear modulus of carotid plaques in a porcine model. Shear wave elastography showed improved assessment of plaque stability when compared to the gray scale median value (Garrard et al., 2015).

Pulse wave velocity imaging is another approach that has been used to calculate arterial wall stiffness (Apostolakis et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2016b). Apostolakis et al. (Apostolakis et al., 2016) used pulse wave velocity to approximate the Young’s modulus in a piecewise manner using the Moens-Kortweg equation. They reported higher pulse wave velocities and stiffness in arterial walls of mice with atherosclerotic and aneurysmal disease when compared to the same mice used as controls at baseline. Thermal strain imaging due to sound speed variations with temperature has also been applied to characterize carotid plaque (Stephens et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2008). Temporal and spatial parameters to assess intra-plaque neovascularization with contrast enhanced ultrasound have been utilized for assessing carotid plaque instability (Zhang et al., 2015; Akkus et al., 2014; Xiong et al., 2009; Staub et al., 2010; Vicenzini et al., 2007).

A robust strain imaging algorithm (McCormick et al., 2012) has been developed and utilized in our laboratory to perform carotid strain imaging. This algorithm uses a hierarchical framework to calculate accumulated axial, lateral and shear strain. In (Wang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016) plaque with adventitia were segmented over a cardiac cycle, and a region of interest (ROI) selected around the location where strain value was maximum. The mean or average value in this region over a cardiac cycle was plotted and used to calculate strain indices for the accumulated temporal strain curves to obtain the maximum accumulated strain and peak to trough strain indices. These strain indices have been shown to be correlated with cognitive function (Wang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016).

As previously described in (Dempsey et al., 2010), with the progression of atherosclerosis disease the lipid pool enlarges and the cellular components in plaque do not stay inert. In fact, they develop their own microvasculature. Rupture of these micro-vessels may lead to entry of embolic content into the blood. All of these events have associated loss of structural stability which can be directly measured using strain imaging of the carotid plaque. The multiple ROI approach used in this work enables characterization of the entire plaque as opposed to the approach by Wang 2016 which assesses a single ROI with maximum strain fluctuations over 10–20 pixels. The multiple ROI approach enables us to fully characterize these biomechanical processes over the entire plaque. Hence our technique with multiple ROI’s is able to better quantify structural instability due to atherosclerotic disease.

In this work we present additional strain indices generated with more sophisticated analysis of the plaque which may provide better correlation values to cognitive function and can be utilized in a multi-variable configuration. Strain indices were correlated to cognitive tests of executive function. This is based on the hypothesis that carotid plaque, whether symptomatic or asymptomatic, is a potential marker of more diffuse cerebral atherosclerotic processes and silent strokes which could be reflected in generalized cognitive pathology compared to age and gender matched controls, a hypothesis supported in a prior publication (Jackson et al., 2016). Moreover, as pointed out in (Dempsey et al., 2017) unstable plaque is not only a marker of emboli location but also of atherosclerotic disease affecting large and small vessels. An extension of this hypothesis is that strain indices would similarly be associated with cognitive pathology, regardless of the symptomatic versus asymptomatic status of the patients. In fact, we argue that “asymptomatic” would be an inaccurate characterization of the status of these patients.

We focused on executive function in this paper given its importance in higher cognitive processes and hypothesized that markers of vessel disease (strain) would be associated with poorer cognition (composite measure of executive function) regardless of symptomatic/asymptomatic status. Executive function refers to a complex set of behavioral processes inherent in overseeing efficient goal directed problem solving behaviors and flexible problem solving and adaption to shifting environmental demands (Loring and Bowden, 2015). Operationally, it is assessed through a matrix of measures that includes but is not limited to working memory, speeded psychomotor and visual skills and measures of problem solving and response inhibition (Strauss et al., 2006).

Materials and Method

Human Subjects

Ultrasound carotid strain imaging and cognition testing were performed on 60 patients (35 males and 25 females) presenting with significant stenosis ≥ 60%, and scheduled for a carotid endarterectomy procedure at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Hospitals and Clinics. Patients were scheduled for carotid endarterectomy based on the criteria described in the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET, 1999) and Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS, 1995) recommendations. Patients participated in the study after providing informed consent using a protocol approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison institutional review board. Patients were classified as symptomatic if they had a previous stroke or a transient ischemic attack and asymptomatic otherwise. 33 patients were therefore classified as symptomatic and 27 patients were asymptomatic. Clinical and demographic details on the patients evaluated in this paper are provided in Table 1. Forty six (46) of these patients were previously evaluated in (Wang et al., 2016) in the single ROI study. We have added 14 new patients in this multiple ROI study. Table 2 presents clinical symptoms experienced by symptomatic patients.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic details on patients presented in terms of their means and standard deviations in brackets.

| Variable | Symptomatic (n = 33) | Asymptomatic (n=27) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.85 (10.90) | 71.00 (7.22) |

| Gender (n/% female) | 12 (36.4%) | 13 (48.1%) |

| BMI | 28.04 (5.77) | 28.52 (3.79) |

| Stenosis (%) | 78.2% | 72.5% |

Table 2.

Clinical symptoms experienced by 33 symptomatic patients. The one patient who had amaurosis fugax had a TIA as well.

| Clinical Symptoms | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Ischemic stokes | 15 |

| Transient Ischemic Attacks (TIA) | 18 |

| Amaurosis fugax | 1 |

Cognitive assessment

All patients underwent a 60-minute neuropsychological test protocol following the protocol guidelines of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Canadian Stroke Network. These tests were always performed before the carotid endarterectomy procedure, generally on the same day as the strain imaging study with the only exception of scheduling conflicts. This protocol was tailored specifically for assessing stroke patients and evaluates fundamental functional domains based on tests of executive function, verbal and nonverbal memory, along with language, and visuospatial ability. Standardized assessment of verbal and performance intelligence quotient (WAIS-IV Information, Digit Span, and Block Design) was also conducted. For the current study, we estimate the correlation between a composite index of executive function and the strain indices developed in this paper. The executive function tests for cognition included: WAIS-IV Digit Symbol which evaluates speeded psychomotor processes, WAIS-IV Digit Span which assesses auditory attention and working memory, TMT-A which evaluates speeded motor and visual attention, and TMT-B which assesses speeded mental flexibility and set shifting ability. A composite index of executive cognition was derived by taking the z-score for each test, derived from comparison to controls, and then generating a mean composite score for each patient.

Strain Estimation

Radiofrequency (RF) data was acquired using an Acuson Siemens S2000 system (Siemens Ultrasound, Mountain View, CA, USA) with an 18L6 transducer with a center frequency of 11.4 MHz. RF data was acquired at the common carotid artery, bifurcation of the internal and external carotid artery and the internal carotid artery along a longitudinal axis view. This was done for both carotids on the left and right side of the neck. Carotid plaque was manually segmented along with the adventitia at the end-diastole frames using the Medical Imaging Interaction Toolkit software by a sonographer on the reconstructed B-mode images generated from the RF data. Both clinical B-mode and color-Doppler cine-clip image loops were also utilized to obtain the best segmentation results.

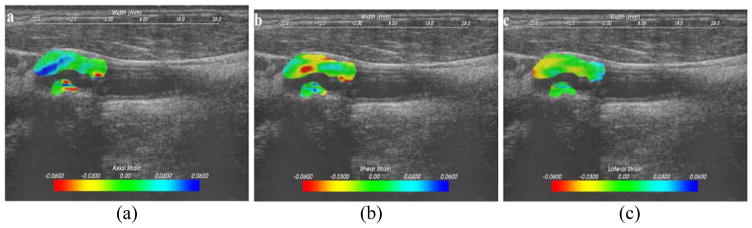

Strain Imaging was performed using a hierarchical two-dimensional block matching algorithm on the acquired RF signals using a normalized two-dimensional cross-correlation approach with iterative Bayesian regularization (McCormick et al., 2012). The matching block has a size of 15 × 28 pixels at the top level and 10 × 18 pixels at the bottom level, with no overlap between the processing blocks. The resolution or the pixel dimensions of the final strain image was 0.2 mm (axial) and 1.35 mm (lateral). The algorithm measured axial strain along the ultrasound beam propagation direction, lateral strain orthogonal to the axial strain and shear strain within the two-dimensional ultrasound scan plane. Strain estimated between RF frames termed incremental strain are rather small as we use frame rates on the order of 27 fps. To completely characterize the strain distribution over a cardiac cycle we use accumulated strain estimates, i.e. strain values were summed up in a Lagrangian format as we temporally progress over a cardiac cycle. A frame skip algorithm is used when inter-frame strain is small as this leads to more accurate strain estimation (McCormick et al., 2012). Finally, the plaque segmentations generated on the end-diastolic frame was tracked over the entire cardiac cycle using the displacement map for deformable registration and segmentation of plaque in subsequent frames. The corresponding accumulated strain images were overlaid on segmented B-mode images, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Axial (a), lateral (b) and shear (c) strain images in the segmented region overlaid on the B-mode image.

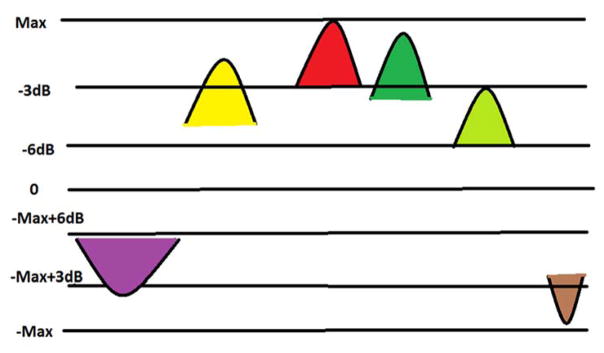

Previous approaches have assessed the temporal variation of the mean strain within a localized ROI surrounding a peak value in the accumulated and segmented strain map. In our approach, we identify and evaluate the temporal progression of multiple such ROI’s and peak strain values present in the segmented plaque. After identification of the maximum peak strain pixel within an imaging plane, we grow this region based on whether the neighboring pixels have strain values within a 3 dB (70.7%) range lower than this peak pixel value in the same frame forming our primary ROI. A minimum of nine surrounding pixels are essential to form an ROI, however, no limits are placed on the extent of the ROI. These pixels are then marked and are not included in any subsequent ROI in all temporal frames. This procedure is then repeated to obtain secondary ROIs within the same imaging plane and other temporal imaging planes over a cardiac cycle, until all such ROI are determined. The only condition that is enforced would be that peak strains within these secondary ROI lie within 3 dB of the maximum strain obtained within the imaging plane. Unstable plaques consist of strain estimates that demonstrate significant deformation over a cardiac cycle. Unstable ROIs are defined as all ROI’s which have maximal strain pixel values upto 3dB (70.7%) lower than the primary ROI’s maximal strain pixel. The minimum strain levels in these ROIs are thus limited to 6 dB (50%) of the primary ROI’s maximal strain pixel.

Figure 2 illustrates the procedure utilized to obtain the multiple ROIs indicated by the different colors in the figure. The algorithm is initiated by finding a maximum pixel which in Figure 2 would correspond to the peak of the red ROI. If this peak is found in frame K, the algorithm picks the closest neighboring points which are within a −3dB (70.7%) range of this peak in frame K. As soon as a neighbor whose value is below the range is encountered, the ROI formation in this imaging plane is stopped. The closest neighbors are found by calculating the Euclidian distance with respect to the peak. This forms our primary ROI. The data points or pixels that form this ROI are then removed from further processing for all temporal frames over the cardiac cycle. The next peak may be located in another frame P, where P may or may not be equal to K. We then form the second ROI by selecting data points in frame P which are within a −3dB range of the peak of that ROI. Let us designate this ROI as the brown ROI in Figure 2. Note that we have intentionally varied the spread of the ROIs to demonstrate that each ROI may contain different number of data points or pixels. Also note that the ROIs may contain positive or negative strain values which represent tensile and compressional strain respectively. As mentioned previously, the algorithm stops identifying ROI when we find a maximum peak which is −3 dB below the primary ROI’s maximum pixel value. Code used to generate the multiple ROI approach can be obtained from the senior and corresponding author of this paper.

Figure 2.

A schematic illustration of the multiple region of interest algorithm described in this paper.

This algorithm for generating multiple ROIs enables us to develop additional strain indices augmenting the ones used previously (Wang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016). These additional indices are described in Table 3. The number of unstable region of interest (NUROI) index attempts to dynamically characterize additional sites of instability present in plaque imaged, while average L1 norm with plaque (AL1NWP) characterizes the differences in strain between the high strain regions generated by our algorithm when compared to the entire plaque region. Mean standard deviation (MSD) looks at the standard deviation and hence the variability in strain distribution over the entire plaque and over a cardiac cycle. Percent of Pixels Selected (PPS) just like NUROI tries to characterize, the percent of the imaged plaque pixels which may be unstable based on the strain distribution. A minor difference between MASI used in this paper versus that previously reported (Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2014) is that the ROI used to estimate MASI is created using a 3 dB region around the maximum strain pixel as described in this paper, while previously the ROI (Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2014) was formed using 10–20 points around the maximum strain pixel. Note that, Upper-AL1NWP and Lower-AL1NWP depend on the presence of relative tensile and compressional strains respectively in the unstable ROIs compared to the rest of the plaque. Note that for some patients one of these two types of strain (tensile or compressional) might not exist and hence these indices would be undefined for these patients. Hence, for the correlation analysis discussed in the following section, if Upper-AL1NWP or Lower-AL1NWP is not defined for a patient then that patient is not included in the correlation analysis for the corresponding strain indices.

Table 3.

Strain indices in addition to the maximum accumulated strain indices and peak-to-trough strain indices reported in previous publications. The significance of these strain indices are also presented in the table.

| No. | Indices | Description | Physical significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maximum Accumulated Strain Index (MASI) | Maximum accumulated average value of the primary ROI (previously used in (Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2014)). If we have P frames and the primary ROI R1 has M number of points and R1ij is the value of the ith strain pixel in jth frame. Then,

|

Maximum strain in a local ROI of maximum instability as defined by relative elevated strain values | |

| 2 | Number of Unstable ROIs (NUROI) | Number of unstable ROIs generated within the imaging plane by the algorithm. These are all the ROIs with maximum strain pixel in 3dB range of primary ROI’s maximum strain pixel. | Number of unstable ROI in the plaque | |

| 3 | Global peak to trough (GPTT) | Difference between the maximum and minimum accumulated average value across ROIs If we have N ROI and P frames. Then,

|

Net temporal strain fluctuation among the unstable ROI | |

| 4 | Primary peak to trough (PPTT) | Difference between the maximum and minimum accumulated average value in the primary ROI over a cardiac cycle (previously used in (Wang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016)). This can be given by:

|

Temporal strain fluctuation in the most unstable ROI | |

| 5 | Maximum localized peak to trough (MLPTT) | Maximum difference between the maximum and minimum accumulated average value within an ROI; estimated over all ROIs. This can be given by:

|

Maximum strain fluctuation in any unstable ROI | |

| 6 | Average L-1 Norm with plaque (AL1NWP) | Average L-1 norm of the difference in the average strain values in all ROI’s with average strain value in entire plaque. This is done per frame over a cardiac cycle. Then the average of all the L-1 norm estimates is computed. If we have N ROIs and P frames. Then,

|

Average additional strain in the unstable regions compared to overall strain in plaque | |

| 7 | Upper-AL1NWP | The AL1NWP procedure implemented for average strain values greater than the strain value in the entire plaque | Average additional tensile strain in the unstable regions compared to overall strain in plaque | |

| 8 | Lower-AL1NWP | The AL1NWP procedure implemented for average strain values lower than the strain value in the entire plaque | Average additional compressional strain in the unstable regions compared to overall strain in plaque | |

| 9 | Mean Standard Deviation (MSD) | Average of the standard deviation in the entire plaque over a cardiac cycle. If we have K pixels in plaque and P frames. Pj is the average strain value of the entire plaque region in the jth frame and Tij is the value of the ith strain pixel in jth frame. |

Average relative strain distribution in plaque | |

| 10 | Percent Selected (PPS) | Percentage of pixels selected by the algorithm and marked as an ROI from the total number of pixels in the segmented plaque. If we have P points selected by the procedure and plaque have K pixels.

|

Percentage of unstable pixels in plaque |

Statistics and Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) Study

Ultrasound strain imaging and cognitive testing was performed independently and the results from each study were blinded to the other. All strain indices were correlated to cognition tests of executive function using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient r and significance level p. Correlation was calculated for three categories of patients, namely symptomatic (n=33), asymptomatic (n=27) and all patients (n=60).

The 60 patients in the study were divided into low and high cognition groups based on mean average z-scores of the patients’ composite executive function index. ROC plots were then generated using strain indices as features for classifying patients into the low and high cognition groups respectively. Independent strain indices which provided Pearson’s coefficient values > 0.5 with significant p-values based on the correlation analysis were selected. We first generated ROC plots using individual strain indices and then ROC plots of classifiers formed with linear combinations of these strain indices were generated. Logistic regression with a 10-fold cross validation was utilized to generate the combined classifiers using Weka 3 (Version 3.8.0, Machine Learning Group at the University of Waikato) (Hall et al., 2009). ROC parameters were generated using ROC-kit software (Version 0.9.1 beta, Metz ROC Software at the University of Chicago), ROC-kit uses a maximum likelihood estimation model to estimate parameters of a binormal distribution (Brown and Davis, 2006). These parameters were fitted to form ROC plots. Area under the curve (AUC) along with upper and lower bounds at a 95% confidence interval (CI) were also obtained from the ROC-kit software.

Results

Strain-Cognition Correlation

In Table 4, we present the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) along with the corresponding p-values for cognition tests of executive function with axial, lateral and shear strain indices respectively for all patients. Similar tables of correlation results for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients are shown in Tables 5 and 6 respectively. All patient groups presented with a negative correlation with the majority of strain indices other than two of the indices, namely the number of unstable ROI (NUROI) and percent of pixels selected (PPS) in the plaque region which showed a positive correlation with cognition tests for executive function. The executive function composite score was composed such that lower z-scores reflected poorer executive function and, conversely, higher z-scores reflected better executive function performance. A negative correlation would therefore indicate that higher strain indices reflected poorer cognition.

Table 4.

Correlation of strain indices with the combined cognition tests for executive function for all patients (n=60).

| Strain Indices | axial | lateral | shear | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r value | p value | r value | p value | r value | p value | |

| MASI | −0.56 | <0.001 | −0.519 | <0.001 | −0.565 | <0.001 |

| NUROI | 0.296 | 0.022 | 0.058 | 0.66 | 0.299 | 0.02 |

| GPTT | −0.502 | <0.001 | −0.59 | <0.001 | −0.519 | <0.001 |

| PPTT | −0.515 | <0.001 | −0.506 | <0.001 | −0.501 | <0.001 |

| MLPTT | −0.522 | <0.001 | −0.512 | <0.001 | −0.523 | <0.001 |

| AL1NWP | −0.575 | <0.001 | −0.491 | <0.001 | −0.581 | <0.001 |

| Upper-AL1NWP | −0.04 | 0.801 | −0.522 | <0.001 | −0.475 | <0.001 |

| Lower-AL1NWP | −0.614 | <0.001 | −0.44 | 0.001 | −0.541 | <0.001 |

| MSD | −0.475 | <0.001 | −0.504 | <0.001 | −0.518 | <0.001 |

| PPS | 0.338 | 0.008 | 0.237 | 0.068 | 0.281 | 0.03 |

Table 5.

Correlation of strain indices with the combined cognition tests for executive function for symptomatic patients (n=33).

| Strain Indices | axial | lateral | shear | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r value | p value | r value | p value | r value | p value | |

| MASI | −0.553 | 0.001 | −0.489 | 0.004 | −0.576 | <0.001 |

| NUROI | 0.409 | 0.018 | 0.064 | 0.725 | 0.259 | 0.146 |

| GPTT | −0.437 | 0.011 | −0.592 | <0.001 | −0.551 | 0.001 |

| PPTT | −0.461 | 0.007 | −0.478 | 0.005 | −0.46 | 0.007 |

| MLPTT | −0.475 | 0.005 | −0.488 | 0.004 | −0.485 | 0.004 |

| AL1NWP | −0.624 | <0.001 | −0.455 | 0.008 | −0.669 | <0.001 |

| Upper-AL1NWP | −0.016 | 0.942 | −0.491 | 0.004 | −0.598 | <0.001 |

| Lower-AL1NWP | −0.66 | <0.001 | −0.413 | 0.021 | −0.693 | <0.001 |

| MSD | −0.506 | 0.003 | −0.556 | 0.001 | −0.62 | <0.001 |

| PPS | 0.362 | 0.038 | 0.314 | 0.075 | 0.317 | 0.073 |

Table 6.

Correlation of strain indices with the combined cognition tests for executive function for asymptomatic patients (n=27).

| Strain Indices | axial | lateral | shear | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r value | p value | r value | p value | r value | p value | |

| MASI | −0.609 | 0.001 | −0.635 | <0.001 | −0.562 | 0.002 |

| NUROI | 0.140 | 0.488 | 0.148 | 0.461 | 0.358 | 0.067 |

| GPTT | −0.656 | <0.001 | −0.573 | 0.002 | −0.432 | 0.024 |

| PPTT | −0.653 | <0.001 | −0.62 | 0.001 | −0.613 | 0.001 |

| MLPTT | −0.652 | <0.001 | −0.609 | 0.001 | −0.623 | 0.001 |

| AL1NWP | −0.549 | 0.003 | −0.58 | 0.002 | −0.514 | 0.006 |

| Upper-AL1NWP | −0.062 | 0.796 | −0.587 | 0.002 | −0.427 | 0.033 |

| Lower-AL1NWP | −0.595 | 0.002 | −0.658 | 0.001 | −0.04 | 0.845 |

| MSD | −0.55 | 0.003 | −0.427 | 0.026 | −0.398 | 0.04 |

| PPS | 0.271 | 0.171 | 0.205 | 0.306 | 0.219 | 0.272 |

ROC curve analysis

As mentioned previously, we picked strain indices which were expected to be independent and/or provided good results from the correlation analysis. These indices included MASI, NUROI, AL1NWP and mean standard deviation. Of these indices NUROI was picked in spite of its poor performance in correlation analysis since preliminary exploration showed that it performed well when used in combination with other indices. This behavior is because the other three indices are a function of the magnitude of strain in plaque while NUROI is an independent parameter which is not related to the magnitude of strain. This independency is shown by calculating the mutual information between the new indices with MASI in Table 7. Mutual information was calculated using a histogram binning approach using the method proposed in (Moddemeijer, 1999). Results in Table 7 show that the mutual information between NUROI and MASI is significantly lower to that between MASI and other indices. MASI, however, was the most consistent index across different patient categories and different strain tensors; hence we looked at classifiers using combination of the other indices with MASI for each type of strain. In the rest of the paper, strain indices will be suffixed with A, L or S denoting axial, lateral and shear strains respectively. The combination of all four indices namely MASI, NUROI, mean standard deviation, AL1NWP will collectively be referred to as ALL.

Table 7.

Mutual Information with MASI, All patients (a) Symptomatic (b) Asymptomatic (c)

| Mutual Information | NUROI | MSD | AL1NWP |

|---|---|---|---|

| axial | −0.03983 | 0.287321 | 0.344483 |

| lateral | −0.03087 | 0.302946 | 0.258149 |

| shear | 0.048827 | 0.381758 | 0.359807 |

| (a) | |||

| Mutual Information | NUROI | MSD | AL1NWP |

|---|---|---|---|

| axial | −0.05952 | 0.438088 | 0.300886 |

| lateral | −0.068 | 0.266718 | 0.351961 |

| shear | −0.0366 | 0.513674 | 0.368112 |

| (b) | |||

| Mutual Information | NUROI | MSD | AL1NWP |

|---|---|---|---|

| axial | −0.04012 | 0.203962 | 0.324346 |

| lateral | −0.03889 | 0.434581 | 0.525114 |

| shear | −0.00647 | 0.210829 | 0.363106 |

| (c) | |||

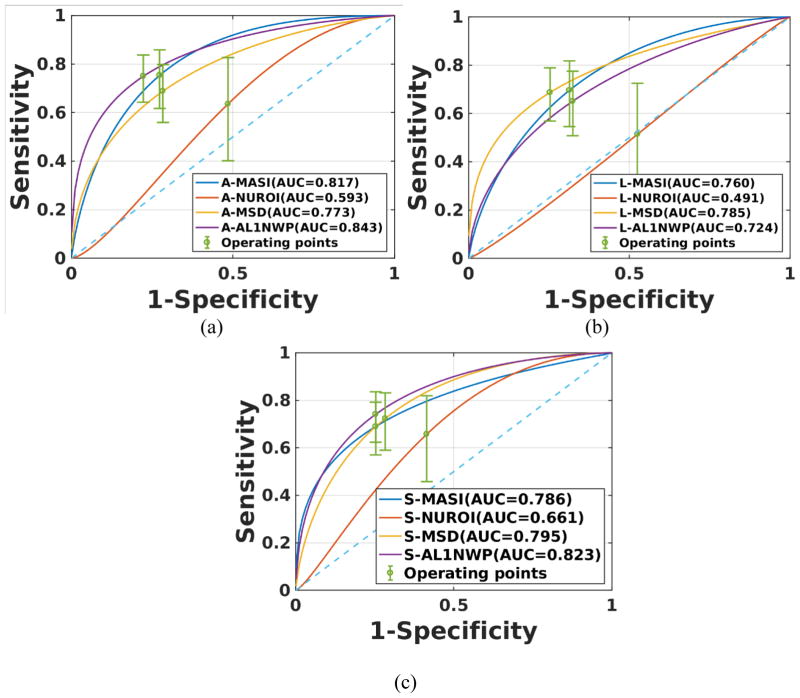

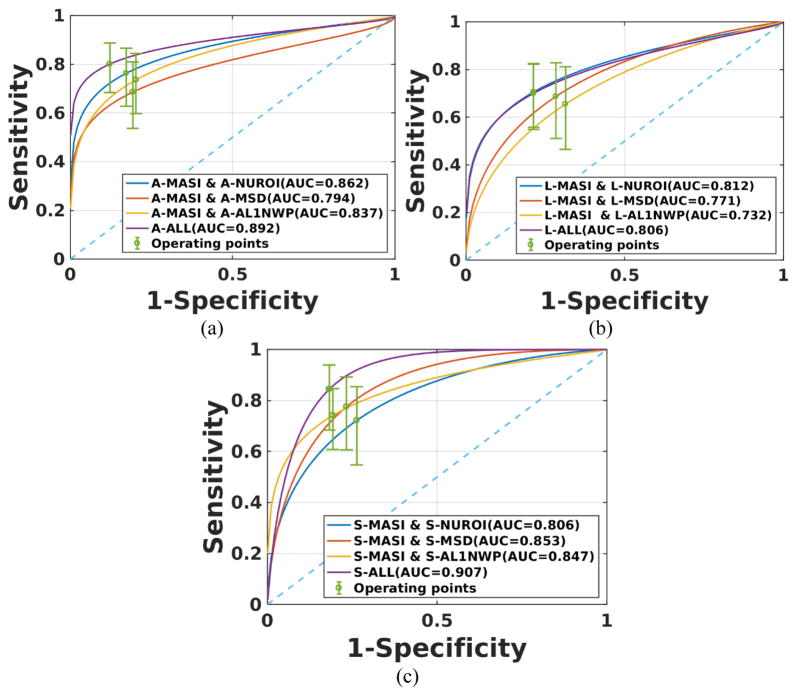

Figure 3, presents classification results for all the individual indices discussed in Table 3, for axial (Fig. 3a), lateral (Fig. 3b) and shear (Fig. 3c) strain imaging over a cardiac cycle to differentiate between low and high cognition over all patients (n=60). The 95% confidence intervals are also shown at the points of operation of the ROC curves. Figure 3 illustrates that AL1NWP performs better than MASI and mean standard deviation for the individual axial and shear strain indices, while mean standard deviation derived from lateral strain estimates performed better than all the other lateral strain indices. NUROI performed poorly when compared to all the other indices because it is an integer number indicating the number of unstable ROI and is not related to magnitude of strain or deformation in plaque or the distribution of strain pixels.

Figure 3.

ROC curves for individual indices for all patients. Results are presented for (a) axial, (b) lateral and (c) shear strains.

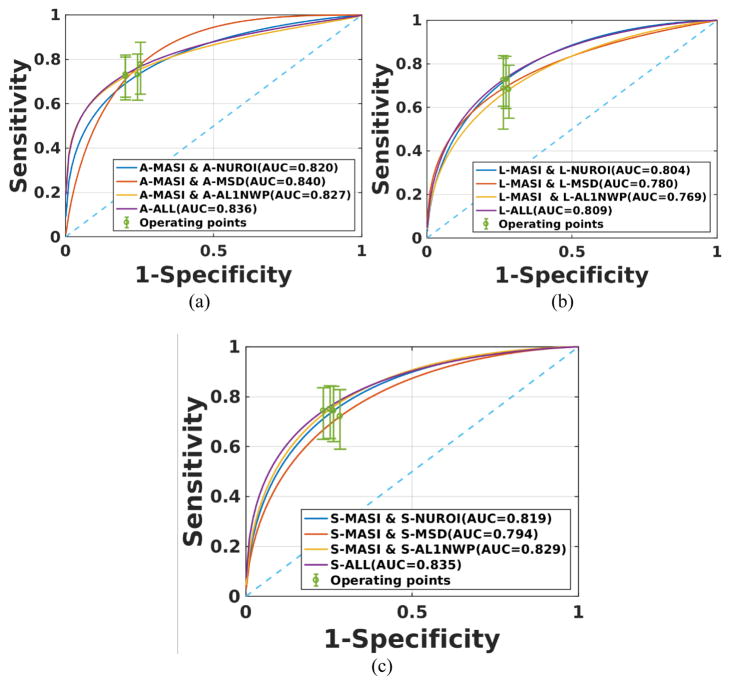

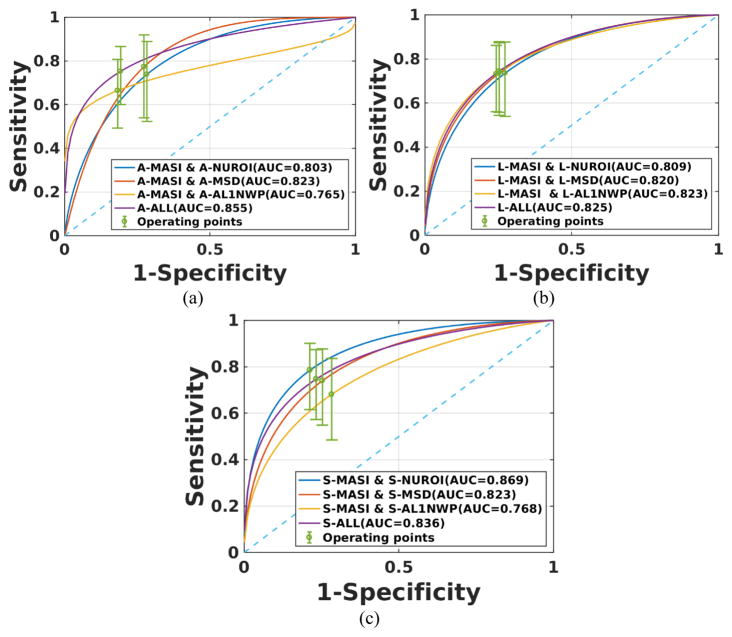

Based on the best performing individual classification results, we combined several of the individual strain indices to obtain combined classifiers. The only exception was NUROI, since as mentioned previously it was found to have the least amount of mutual information with the other indices. The ROC curves for classifiers that use linear combinations of strain indices for all patients are shown in Figure 4. The combination of MASI with mean standard deviation, NUROI and AL1NWP provided the best classification performance for axial, lateral and shear strains respectively. However, the combined individual classifiers in the ALL category did not demonstrate a significant improvement over the best performing classifiers that included only two of the indices.

Figure 4.

ROC curves for a combination of two of the strain indices for all patients. Results are presented for (a) axial, (b) lateral and (c) shear strains.

Figure 5 presents ROC curves for linear combination of strain indices for symptomatic patients. The combination of MASI and NUROI provides improved classification results when compared to MASI with mean standard deviation or AL1NWP for axial and lateral strains. On the other hand, for shear strains MASI with mean standard deviation or AL1NWP did better than MASI with NUROI. The ALL indices classifier provides better performance compared to the best classifier with two indices for axial and lateral strains, respectively.

Figure 5.

ROC curves for a combination of two of the strain indices for symptomatic patients. Results are presented for (a) axial, (b) lateral and (c) shear strains.

For asymptomatic patients, the corresponding ROC curves are shown in Figure 6. The combination of mean standard deviation with MASI performed best among the combination for two indices for axial strain. However, there was no significant difference between any of the combinations of strain indices for lateral strain. For shear strain, however, NUROI with MASI provided the best performance among all the combinations. The ALL indices classifier provided better performance only for axial strain.

Figure 6.

ROC curves for a combination of two of the strain indices and all indices for asymptomatic patients. Results are presented for (a) axial, (b) lateral and (c) shear strains.

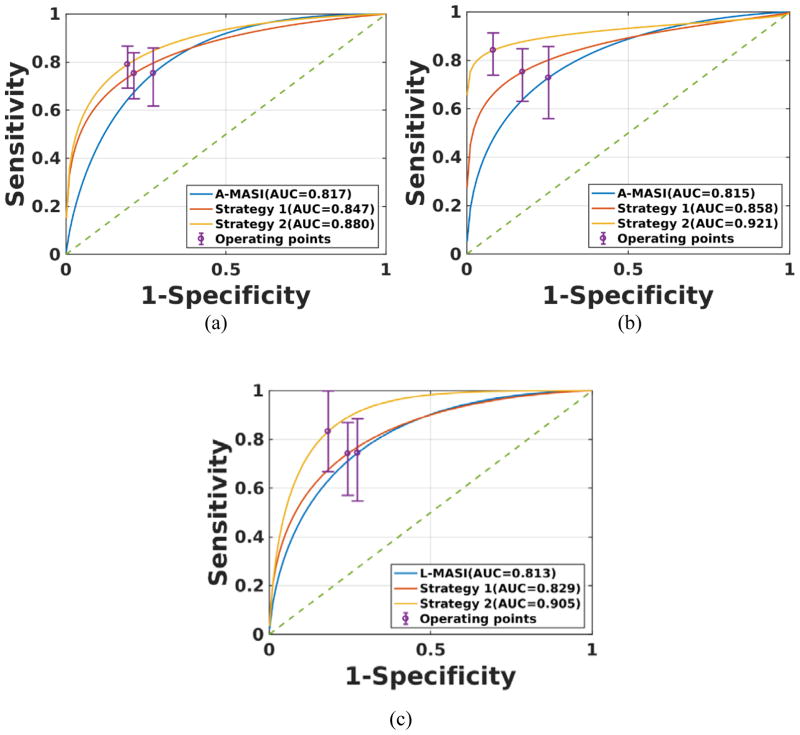

Finally, to obtain an optimal set of indices that can be utilized as classifiers we implemented two strategies. We first restricted the number of indices to three to avoid any overfitting. The first strategy was to pick three indices that provided the best correlation with executive cognition. The second strategy was to select the index with the best individual ROC performance and then select two of the three NUROI indices from the axial, lateral or shear strain images respectively. The rationale behind choosing NUROI was that these indices had shown independence based on the mutual information criteria.

Based on the criteria used for strategy 1, we selected A-AL1NWP, S-MASI and S-AL1NWP for all patients, A-AL1NWP, S-MSD and S-AL1NWP for symptomatic patients and A-MASI, L-MASI and L-AL1NWP for asymptomatic patients. For strategy two the indices for all patients were A-AL1NWP with L-NUROI and S-NUROI, for symptomatic patients the indices were S-MSD with A-NUROI and L-NUROI and for asymptomatic patients L-MASI with L-NUROI and S-NUROI were the three indices. To demonstrate the relative differences in classification in Figure 7 we include the best performing MASI ROC plot, along with ROC plots for strategy 1 and strategy 2, respectively. These are shown for all, symptomatic and asymptomatic patients in Figure 7a, 7b and 7c respectively. The MASI classifier would represent the performance obtained based on our previous work reported in (Wang et al., 2016). Observe that the plots in Figure 7 demonstrate that while strategy 1 provides an improvement over the MASI classifier, strategy 2 provided even better classification results.

Figure 7.

ROC curves for the best classifiers. Results are presented for (a) all, (b) symptomatic and (c) asymptomatic patients.

Discussion

Analysis of the strain distribution in carotid plaque is important to detect plaques prone to rupture with fatigue over a cardiac cycle. When compared to our previously developed MASI and peak-to-trough strain indices over a single ROI, the new indices assess the overall characteristics of the plaque strain distribution instead of being restricted to analysis over a single ROI. AL1NWP performs in a similar fashion to MASI except that it incorporates multiple ROI’s and also includes the average temporal behavior of the ROI’s since it involves an average or mean computation over the entire cardiac cycle. The indices NUROI and PPS are independent of the underlying strain values in the plaque and are primarily a function of the underlying strain distribution. Mean standard deviation on the other hand utilizes an average of the standard deviations of strain over the entire cardiac cycle and hence assesses the average temporal behavior or variability of both strain values leading to local maxima and the underlying strain distribution.

Although, the strain indices NUROI and PPS were not significantly correlated, they show a weak relationship on ROC analysis for individual indices. However, they provide significant improvement when combined with other indices such as MASI as they provide independent uncorrelated information on plaque stability. For example, S-NUROI presented with an r= 0.299 value with p=0.020, and A-PPS had r=0.338 with p=0.008 for all patients with the composite measure of executive function. As previously described, whenever these two features showed a relationship it was opposite in nature to the remaining strain indices. That is, higher NUROI and PPS value meant better cognition and vice versa. A possible explanation for this behavior is that with unstable plaque MASI presents with high strain value than the rest of the plaque and the −3 dB clustering algorithm used picks up lower number of ROIs and a lower percentage of points get selected because of a higher threshold. On the other hand, for a stable plaque, MASI is stable with lower strain values and hence the −3 dB clustering algorithm picks up a larger number of ROI’s and percentage of points because of a subsequently lower threshold. Hence for NUROI and PPS, higher integer values correspond to stable plaque and hence better executive function in patients. This information combined with MASI resulted in an improved classifier as illustrated by the strategy 2 plots in Figure 7.

The use of strategy 1 in Figure 7 also showed an improvement over the MASI classifier alone. However, this improvement was due to the better performance of the newer indices like AL1NWP and MSD rather than the combination of the indices. This can be verified by evaluating the ROC plots for the axial strain estimates in Figure 2 where A-AL1NWP presents with an AUC of 0.843 while in Figure 7a, strategy 1 which included A-AL1NWP as one of its features presents with an AUC of 0.847 which is not significantly different. However, in strategy 2 we obtain an AUC of 0.880 where we used A-AL1NWP and two of the NUROI indices which is an improvement.

Previous work had reported stronger correlation with lateral indices for asymptomatic patients when compared to symptomatic patients with the hypothesis that plaque might have previously been ruptured in symptomatic patients when compared to intact plaque in asymptomatic patients (Wang et al., 2016). In this study, we observe the same behavior for L-MASI with r = −0.489 and r = −0.635 for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients respectively. However, classifiers using combination of MASI with NUROI partially mitigate this effect since these classifiers had values of 0.812 and 0.809 using the lateral indices for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients respectively as shown in Figure 4b and 5b.

Another trend observed in our study was that AL1NWP provided better correlation when compared to MASI for symptomatic patients (see Table 5) for axial and shear strain images when compared to asymptomatic patients (see Table 6). This may be due to the fact that AL1NWP provides a global estimate of the structural stability of plaque as opposed to MASI which is limited to a single ROI at the most unstable region for a given plaque. We hypothesize that in symptomatic participants, the plaque may have undergone multiple fissures and possible plaque rupture which would contribute to the release of larger emboli, resulting in cerebrovascular symptoms of ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack or amaurosis fugax. Whereas in asymptomatic patients, plaques may not have ruptured and thus, the emboli shed from the plaque itself could be much smaller and therefore did not result in a frank cerebrovascular symptom, but may have contributed to possible cognitive impairment/decline. The amount of fissuring in the plaque in both groups could be similar as the AL1NWP values for both groups were not significantly different (p=0.91 for axial-AL1NWP with two sample student t-test). The MSD indices also account for both the variability of strain due to micro-vascular fissures and the variability encountered with a large lipid pool when compared to rest of the plaque. Hence, MSD also provided a higher correlation for symptomatic patients when compared to MASI for lateral and shear strains (see Table 5) when compared to asymptomatic patients ( see Table 6).

The results reported in this paper indicate that no specific type of strain tensor imaging (axial, lateral or shear) would outperform all of the others in a consistent fashion. This is also observed from Figure 7 where combinations across strain tensor images provided better performance as compared to results in Figures 3–6. Analysis on a larger number of patients, however, is needed to ascertain and justify why some indices perform better for specific strain tensor images and categories of patients. However, we demonstrate that robust and improved classifiers are obtained with the additional new indices utilizing multiple ROIs reported in this paper.

Conclusion

We demonstrated improved classification performance with cognitive measures associated with executive function with our additional strain indices beyond the maximum accumulated strain indices and the local peak to trough strain indices that were described previously. The new indices based on strain distribution maxima in the plaque like AL1NWP and MSD demonstrate a similar relationship to cognition as MASI while the indices NUROI and PPS present with an opposing relationship to cognition. The classifiers formed using the combination of indices were shown to perform better than using the original MASI indices and hence contributes to making the classification between patients with high and low cognition stronger. This is demonstrated by classifiers with three of the indices providing AUC values of 0.880, 0.921 and 0.905 for all, symptomatic and asymptomatic patients respectively, whereas the best corresponding MASI classifiers had AUC values of 0.817, 0.815 and 0.813 respectively. Since decline in the cognition measure of executive function is related to events like strokes, transient ischemic attacks and silent strokes, the relationship of the strain values and strain distribution to cognitive deficits demonstrates that multiple strain maxima and the underlying strain distribution and variability in plaque may provide additional new information and a relationship to the probability of plaque rupture.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R21 EB010098-02, R01 NS064034-05, and 2R01 CA112192-08. This research was performed using the computational resources provided by the UW-Madison Center for High Throughput Computing (CHTC) in the Department of Computer Sciences. The CHTC is supported by UW-Madison and the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, and is an active member of the Open Science Grid, which is supported by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

A List of Abbreviations

- AL1NWP

Average L-1 Norm with Plaque

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

- GPTT

Global Peak to Trough

- MASI

Maximum Accumulated Strain Indices

- MLPTT

Maximum localized peak to trough

- MSD

Mean Standard Deviation

- NASCET

North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial

- NUROI

Number of Unstable Region of Interest

- PPTT

Primary peak to trough

- PPS

Percent of Pixels Selected

- ROC

Receiver Operator Characteristic

- ROI

Region of Interest

References

- ACAS. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Jama. 1995;273:1421–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkus Z, Hoogi A, Renaud G, van den Oord SC, Gerrit L, Schinkel AF, Adam D, de Jong N, van der Steen AF, Bosch JG. New quantification methods for carotid intra-plaque neovascularization using contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2014;40:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolakis IZ, Nandlall SD, Konofagou EE. Piecewise pulse wave imaging (pPWI) for detection and monitoring of focal vascular disease in murine aortas and carotids in vivo. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2016;35:13–28. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2453194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman SE, Wang X, Mitchell CC, Kundu B, Jackson DC, Wilbrand SM, Varghese T, Hermann BP, Rowley HA, Johnson SC. The relationship between carotid artery plaque stability and white matter ischemic injury. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2015;9:216–22. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, Bacharach JM, Barr JD, Bush RL, Cates CU, Creager MA, Fowler SB, Friday G, Hertzberg VS, McIff EB, Moore WS, Panagos PD, Riles TS, Rosenwasser RH, Taylor AJ. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Vascular medicine (London, England) 2011;16:35–77. doi: 10.1177/1358863X11399328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CD, Davis HT. Receiver operating characteristics curves and related decision measures: A tutorial. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 2006;80:24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Czernuszewicz TJ, Homeister JW, Caughey MC, Farber MA, Fulton JJ, Ford PF, Marston WA, Vallabhaneni R, Nichols TC, Gallippi CM. Non-invasive in vivo characterization of human carotid plaques with acoustic radiation force impulse ultrasound: Comparison with histology after endarterectomy. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2015;41:685–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey RJ, Varghese T, Jackson DC, Wang X, Meshram NH, Mitchell CC, Hermann BP, Johnson SC, Berman SE, Wilbrand SM. Carotid atherosclerotic plaque instability and cognition determined by ultrasound-measured plaque strain in asymptomatic patients with significant stenosis. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2017:1–9. doi: 10.3171/2016.10.JNS161299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey RJ, Vemuganti R, Varghese T, Hermann BP. A review of carotid atherosclerosis and vascular cognitive decline: a new understanding of the keys to symptomology. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:484. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000371730.11404.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty JR, Dahl JJ, Kranz PG, El Husseini N, Chang H-C, Chen N-k, Allen JD, Ham KL, Trahey GE. Comparison of acoustic radiation force impulse imaging derived carotid plaque stiffness with spatially registered MRI determined composition. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2015;34:2354–65. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2432797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard J, Ummur P, Nduwayo S, Kanber B, Hartshorne T, West K, Moore D, Robinson T, Ramnarine K. Shear Wave Elastography May Be Superior to Greyscale Median for the Identification of Carotid Plaque Vulnerability: A Comparison with Histology. Ultraschall in der Medizin-European Journal of Ultrasound. 2015;36:386–90. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1399676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glagov S, Zarins C, Giddens D, Ku D. Hemodynamics and atherosclerosis. Insights and perspectives gained from studies of human arteries. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 1988;112:1018–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, Frank E, Holmes G, Pfahringer B, Reutemann P, Witten IH. The WEKA data mining software: an update. ACM SIGKDD explorations newsletter. 2009;11:10–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H, Saris A, Vaka N, Nillesen M, de Korte C. Ultrafast vascular strain compounding using plane wave transmission. Journal of biomechanics. 2014;47:815–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen HH, de Borst GJ, Bots ML, Moll FL, Pasterkamp G, de Korte CL. Validation of noninvasive in vivo compound ultrasound strain imaging using histologic plaque vulnerability features. Stroke. 2016;47:2770–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H, Kanai H. Simultaneous imaging of artery-wall strain and blood flow by high frame rate acquisition of RF signals. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control. 2008;55:2626–39. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2008.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Pan X, He Q, Huang M, Huang L, Zhao X, Yuan C, Bai J, Luo J. Ultrasound-Based Carotid Elastography for Detection of Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaques Validated by Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2016a;42:365–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Su Y, Zhang H, Qian L-X, Luo J. Comparison of Different Pulse Waveforms for Local Pulse Wave Velocity Measurement in Healthy and Hypertensive Common Carotid Arteries in Vivo. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2016b;42:1111–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DC, Sandoval-Garcia C, Rocque BG, Wilbrand SM, Mitchell CC, Hermann BP, Dempsey RJ. Cognitive Deficits in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Surgical Candidates. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2016;31:1–7. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acv082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Huang S-W, Hall TL, Witte RS, Chenevert TL, O’Donnell M. Arterial vulnerable plaque characterization using ultrasound-induced thermal strain imaging (TSI) IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2008;55:171–80. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.900565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korukonda S, Nayak R, Carson N, Schifitto G, Dogra V, Doyley MM. Noninvasive vascular elastography using plane-wave and sparse-array imaging. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control. 2013;60:332–42. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2013.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Du L, Wang F, Luo X. Assessment of the arterial stiffness in patients with acute ischemic stroke using longitudinal elasticity modulus measurements obtained with Shear Wave Elastography. Medical ultrasonography. 2016;18:182–9. doi: 10.11152/mu.2013.2066.182.wav. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loring DW, Bowden S. INS Dictionary of Neuropsychology and Clinical Neurosciences. Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Majdouline Y, Ohayon J, Keshavarz-Motamed Z, Cardinal M-HR, Garcia D, Allard L, Lerouge S, Arsenault F, Soulez G, Cloutier G. Endovascular shear strain elastography for the detection and characterization of the severity of atherosclerotic plaques: In vitro validation and in vivo evaluation. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2014;40:890–903. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick M, Varghese T, Wang X, Mitchell C, Kliewer M, Dempsey R. Methods for robust in vivo strain estimation in the carotid artery. Physics in medicine and biology. 2012;57:7329. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/22/7329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moddemeijer R. A statistic to estimate the variance of the histogram-based mutual information estimator based on dependent pairs of observations. Signal Processing. 1999;75:51–63. [Google Scholar]

- NASCET. The North American symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial surgical results in 1415 patients. Stroke. 1999;30:1751–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.9.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ophir J, Cespedes I, Ponnekanti H, Yazdi Y, Li X. Elastography: a quantitative method for imaging the elasticity of biological tissues. Ultrasonic imaging. 1991;13:111–34. doi: 10.1177/016173469101300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramnarine KV, Garrard JW, Kanber B, Nduwayo S, Hartshorne TC, Robinson TG. Shear wave elastography imaging of carotid plaques: feasible, reproducible and of clinical potential. Cardiovascular ultrasound. 2014;12:1. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-12-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribbers H, Lopata RG, Holewijn S, Pasterkamp G, Blankensteijn JD, De Korte CL. Noninvasive two-dimensional strain imaging of arteries: validation in phantoms and preliminary experience in carotid arteries in vivo. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2007;33:530–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocque BG, Jackson D, Varghese T, Hermann B, McCormick M, Kliewer M, Mitchell C, Dempsey RJ. Impaired cognitive function in patients with atherosclerotic carotid stenosis and correlation with ultrasound strain measurements. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2012;322:20–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Mitchell CC, McCormick M, Kliewer MA, Dempsey RJ, Varghese T. Preliminary in vivo atherosclerotic carotid plaque characterization using the accumulated axial strain and relative lateral shift strain indices. Physics in medicine and biology. 2008;53:6377. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/22/008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stary H. Composition and classification of human atherosclerotic lesions. Virchows Archiv A. 1992;421:277–90. doi: 10.1007/BF01660974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stary HC, Chandler AB, Dinsmore RE, Fuster V, Glagov S, Insull W, Rosenfeld ME, Schwartz CJ, Wagner WD, Wissler RW. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1995;92:1355–74. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub D, Patel MB, Tibrewala A, Ludden D, Johnson M, Espinosa P, Coll B, Jaeger KA, Feinstein SB. Vasa vasorum and plaque neovascularization on contrast-enhanced carotid ultrasound imaging correlates with cardiovascular disease and past cardiovascular events. Stroke. 2010;41:41–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.560342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens DN, Mahmoud AM, Ding X, Lucero S, Dutta D, Francois T, Chen X, Kim K. Flexible integration of high-imaging-resolution and high-power arrays for ultrasound-induced thermal strain imaging (US-TSI) IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control. 2013;60:2645–56. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2013.2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss E, Sherman E, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests. 3. Nueva York, USA: Oxford U. Press; 2006. [Links] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese T. Quasi-static ultrasound elastography. Ultrasound clinics. 2009;4:323–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cult.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicenzini E, Giannoni MF, Puccinelli F, Ricciardi MC, Altieri M, Di Piero V, Gossetti B, Valentini FB, Lenzi GL. Detection of carotid adventitial vasa vasorum and plaque vascularization with ultrasound cadence contrast pulse sequencing technique and echo-contrast agent. Stroke. 2007;38:2841–3. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.487918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Jackson DC, Mitchell CC, Varghese T, Wilbrand SM, Rocque BG, Hermann BP, Dempsey RJ. Classification of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Patients with and without Cognitive Decline Using Non-invasive Carotid Plaque Strain Indices as Biomarkers. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2016;42:909–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Jackson DC, Varghese T, Mitchell CC, Hermann BP, Kliewer MA, Dempsey RJ. Correlation of cognitive function with ultrasound strain indices in carotid plaque. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2014;40:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Mitchell CC, Varghese T, Jackson DC, Rocque BG, Hermann BP, Dempsey RJ. Improved Correlation of Strain Indices with Cognitive Dysfunction with Inclusion of Adventitial Layer with Carotid Plaque. Ultrason Imaging. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0161734615589252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisnant JP, Basford JR, Bernstein EF, Cooper ES, Dyken ML, Easton JD, Little JR, Marler JR, Millikan CH, Petito C. Classification of cerebrovascular diseases III. Stroke. 1990;21:637–76. [Google Scholar]

- Widman E, Caidahl K, Heyde B, D’hooge J, Larsson M. Ultrasound speckle tracking strain estimation of in vivo carotid artery plaque with in vitro sonomicrometry validation. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2015;41:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman E, Maksuti E, Amador C, Urban MW, Caidahl K, Larsson M. Shear wave elastography quantifies stiffness in Ex vivo porcine artery with stiffened arterial region. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2016;42:2423–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L, Deng Y-B, Zhu Y, Liu Y-N, Bi X-J. Correlation of Carotid Plaque Neovascularization Detected by Using Contrast-enhanced US with Clinical Symptoms 1. Radiology. 2009;251:583–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2512081829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Li C, Han H, Dai W, Shi J, Wang Y, Wang W. Spatio-temporal Quantification of Carotid Plaque Neovascularization on Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound: Correlation with Visual Grading and Histopathology. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2015;50:289–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]