Abstract

Parkinson’s disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, with only partial symptomatic therapy and no mechanism-based therapies. The accumulation and aggregation of α-synuclein is causatively linked to the sporadic form of the disease, which accounts for 95% of cases. The pathology is a result of a gain of toxic function of misfolded α-synuclein conformers, which can template the aggregation of soluble monomers and lead to cellular dysfunction, at least partly by interfering with membrane fusion events at synaptic terminals. Here, we discuss the transcellular propagation and intracellular trafficking of α-synuclein and posit that endosomal processing could be a point of convergence between these two routes. Understanding these events will clarify the therapeutic potential of enzymes that regulate protein trafficking and degradation in synucleinopathies.

Aggregated α-synuclein can spread from cell to cell by uptake and release, templating further aggregation that leads to disease (e.g., Parkinson’s). Endosomal processing may serve as a point of convergence for these processes.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, affecting 1% of people over the age of 60. Clinically, it is characterized primarily by a movement disorder causing resting tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, postural instability, and diverse nonmotor symptoms including dementia, which in community-based studies, was reported in up to 80% of patients with a long disease duration (Hely et al. 2008). This latter finding indicates that PD is a diffuse neurodegenerative disorder. Similarly, detailed neuropathological studies have shown that one of the cardinal histological features, the intraneuronal inclusions called Lewy pathology, is detected in numerous cortical areas and often correlates with the extent of cognitive decline (Spillantini et al. 1997; Goedert et al. 2013). Despite this diffuse evolution, the presentation to health services is commonly a result of the loss of a critical number of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (Lees et al. 2009), but in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), dementia may be the presenting feature.

The identification of causative genes in familial cases and their study in animal models has suggested new intracellular and cell-non-autonomous mechanisms of pathogenicity. A major challenge is the prioritization and validation of those mechanisms that can best explain the histological characteristics of the disease (i.e., the intraneuronal accumulation of α-synuclein in Lewy pathology, which is a sine qua non feature of the most common form of sporadic PD and detected postmortem in >95% of cases). α-Synuclein is also the major component of glial cytoplasmic inclusions that define multiple system atrophy (MSA), a movement disorder characterized by cerebellar ataxia, parkinsonism, and autonomic dysfunction. In MSA, unlike PD and DLB, many α-synuclein inclusions are found in glial cells (Spillantini et al. 1998a,b).

Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms that underpin the pathogenicity of α-synuclein is important for the development of therapies that aim to benefit the vast majority of patients with PD, DLB, and MSA. Besides its presence in the form of insoluble inclusions in all cases of disease (Goedert 2015), the pathogenicity of α-synuclein is also supported by the following: (1) cases of PD and DLB are caused by missense mutations or multiplications in the α-synuclein gene (SNCA) (Polymeropoulos et al. 1997; Goedert 2015); (2) polymorphisms in SNCA are the most common risk factor for idiopathic PD and MSA (Goedert 2015); and (3) overexpression of α-synuclein is associated with aggregation and neuronal toxicity in model organisms (Feany and Bender 2000; Osterberg et al. 2015). Mechanistic studies in vitro and in vivo suggest that aggregated α-synuclein is toxic through a gain-of-function mechanism (reviewed in Tofaris and Spillantini 2007). This gain of toxic function is caused by α-synuclein misfolding, which acts as a template for further aggregation and leads to cellular dysfunction, at least partly, by interfering with fusion events in vesicle recycling (Perrett et al. 2015).

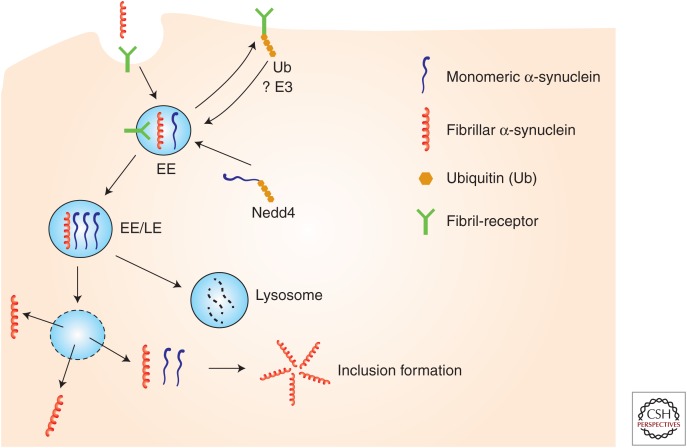

In this review, we discuss the transcellular propagation and intracellular trafficking of α-synuclein and posit that endosomal processing could be a point of convergence between these routes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed model for the propagation and intracellular trafficking of α-synuclein at the endosome. α-Synuclein fibrils bind to surface receptors on neuronal plasma membrane such as LAG3 and are internalized in endosomes. Receptor levels per se may be regulated by ubiqutination and endosomal processing. Intracellular α-synuclein is targeted to endosomes (e.g., by Nedd4-dependent ubiquitination), where it may encounter internalized fibrils. The acidic pH of endosomes would be a permissive environment for template-induced misfolding of monomers and amplification of fibrillar conformers. Such conformers may be degraded by lysosomes or under certain conditions (e.g., by endosomal rupture) released in the cytosol where they could act as seeds for further aggregation of cytosolic α-synuclein monomers. EE, Early endosome; LE, late endosome; E3, ubiquitin ligase; Ub, ubiquitin.

TRANSCELLULAR PROPAGATION OF α-SYNUCLEIN

α-Synuclein is enriched in presynaptic nerve terminals and loosely associates with membranes through its N-terminal part. This interaction with lipids induces its folding into α-helical conformers (Burré et al. 2014). In cells, upon cross-linking, α-synuclein can be detected as metastable oligomers, predominantly tetramers, which are in equilibrium with monomers (Dettmer et al. 2015). In solution, monomeric α-synuclein is natively unfolded with a propensity to self-assemble into β-sheet-rich filaments, with the same ultrastructure as those extracted from Lewy pathology (Spillantini et al. 1998a,b). In vitro, the conversion of soluble α-synuclein into amyloid fibrils typically occurs after a lag phase that is followed by a rapid increase in fibril formation and is concentration-dependent (Li et al. 2001). This suggests that a critical amount of α-synuclein in amyloid precursors may stochastically form in solution, acting as “seeds” to promote the recruitment of unfolded α-synuclein in amyloidogenic permissive structures and the synergistic formation of amyloid fibrils. In addition, α-synuclein was shown to assemble into two different strains with different structures and seeding properties (Bousset et al. 2013). Therefore, at least in vitro, α-synuclein possesses properties that could explain its pathogenicity by a conformational templating mechanism. Accordingly, the A53T, H50Q, and E46K α-synuclein mutations have consistently been shown to increase the rate of self-aggregation (Conway et al. 1998; Giasson et al. 2001; Choi et al. 2004; Greenbaum et al. 2005; Ghosh et al. 2013). On the other hand, not all mutations share this property; for example, the A30P, G51D, and A53E mutations reduce the rate of self-aggregation, and also impair the ability of α-synuclein to bind to lipids and brain vesicles (Jensen et al. 1998; Fares et al. 2014; Ghosh et al. 2014).

The concept of pathological templating gained impetus by the finding of Lewy pathology in embryonic neural grafts 11–16 years after transplantation into the brains of people with PD (Kordower et al. 2008; Li et al. 2008). Together, these histological and biochemical studies raised the possibility that misfolded α-synuclein from the host PD brain passed into the grafted cells and templated the conversion of soluble α-synuclein similar to infectious cases of human prion diseases. These studies reinvigorated an earlier suggestion by Braak et al. (2003), whose postmortem neuropathological studies have indicated that in the majority of cases, Lewy pathology evolves along interconnected brain networks that begin in the dorsal motor nucleus of the glossopharyngeal and vagal nerves or the olfactory bulb and the anterior olfactory nucleus, and spread rostrally. It is noteworthy that Lewy pathology is also found in the enteric nervous system, raising the possibility that spread of pathology may also occur between the gastrointestinal system and the brain. In support of gut-to-brain spreading, vagotomy has been associated with a reduced risk of PD (Gray et al. 2015), whereas in animal models, the gut-to-brain evolution of α-synuclein pathology has been reported following the intragastric infusion of rotenone (Pan-Montojo et al. 2010).

In transgenic (Tg) mice, human α-synuclein can transit to nerve cells grafted into the hippocampus (Desplats et al. 2009). Moreover, intracerebral inoculation of brain tissue from symptomatic mice accelerated α-synuclein aggregation in the brains of presymptomatic Tg mice, leading to an earlier onset of neurological symptoms (Mougenot et al. 2012). Unlike induced Aβ and tau assemblies, α-synuclein inclusions in this model were associated with neurodegeneration. Evidence for assembled α-synuclein behaving like a prion has come from the injection of MSA brain extracts into heterozygous mice Tg for A53T human α-synuclein (Watts et al. 2013; Prusiner et al. 2015). Intracerebral injection led to the death of the mice and the development of abundant α-synuclein inclusions. Unlike MSA, where α-synuclein inclusions are mainly found in glial cells, the induced inclusions were present in nerve cells. Injection of recombinant α-synuclein assemblies into the hind limb muscle of Tg mice also induced cerebral α-synuclein aggregation and a neuronal phenotype that was mitigated by transection of the sciatic nerve (Sacino et al. 2013). Spreading of α-synuclein aggregates from the periphery to the brain has also been shown in wild-type (WT) rats (Holmqvist et al. 2014; Peelaerts et al. 2015), but it remains unknown whether these aggregates can seed aggregation of endogenous α-synuclein.

Intrastriatal injection of recombinant mouse α-synuclein assemblies into WT mice gave rise to α-synuclein inclusions and some brain dysfunction (Luk et al. 2012). The same fibrils induced the formation of α-synuclein inclusions in primary cortical neurons from WT mice. Intranigral injection of α-synuclein assemblies into WT mice and monkeys resulted in the formation of inclusions of endogenous α-synuclein (Masuda-Suzukake et al. 2013; Recasens et al. 2014). Based on ultrastructure, two forms of misfolded α-synuclein species have been described (Bousset et al. 2013; Peelaerts et al. 2015) that appear to have distinct pathogenic properties: ribbons and fibrils. When injected into the substantia nigra of the rat, ribbons gave rise to Lewy pathology, whereas fibrils, which did not seed Lewy pathology, led to a loss of dopaminergic neurons. It remains to be seen whether ribbons and fibrils of α-synuclein have their counterparts in human diseases.

INTRACELLULAR TRAFFICKING OF α-SYNUCLEIN

Many studies have shown that monomeric and oligomeric forms of α-synuclein can be taken up and released from various cell types, including neurons, and α-synuclein has been detected in extracellular fluids, such as plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (El-Agnaf et al. 2003). When overexpressed, α-synuclein is also released in exosomes (Emmanouilidou et al. 2010), which are derived from multivesicular bodies. In culture, α-synuclein is secreted by neurons (Lee et al. 2005), and its secretion is increased following stress, including oxidation and inhibition of lysosomal function (Jang et al. 2010). Interestingly, under such conditions, there is increased translocation of α-synuclein into vesicles and release of a predominantly oligomeric form (Desplats et al. 2009; Jang et al. 2010; Danzer et al. 2011). These studies suggest that structurally abnormal or damaged α-synuclein may be shuttled into vesicles and released from neuronal cells via exocytosis. It is now established that fibrillar and oligomeric α-synuclein can also be internalized by endocytosis (reviewed in Lee et al. 2014). Addition of preformed fibrils (PFFs) to primary neurons can induce the formation of intracellular inclusions, which are stained by antibodies specific for α-synuclein phosphorylated at serine 129 (Volpicelli-Daley et al. 2011). Using microfluidic devices to separate the soma and axonal projections from separate but adjacent and synapsed primary neuronal populations, it has been shown that, following uptake, PFFs can move bidirectionally along axons, but synaptic contacts are apparently not required for interneuronal transfer (Volpicelli-Daley et al. 2011; Freundt et al. 2012). It is, therefore, possible that α-synuclein aggregates produced in one neuron can be transmitted to a neighboring cell by exocytosis and endocytosis. Accordingly, disruption of the endosomal GTPase Rab5a and pharmacological inhibition of endocytosis reduced the uptake of α-synuclein (Sung et al. 2001; Hansen et al. 2011). In addition, changes in the expression of Rab11, a GTPase of the recycling endosome, promoted the secretion of α-synuclein and decreased its aggregation and toxicity in Drosophila (Breda et al. 2015). The relevance of endosomal processing in the propagation of proteopathic assemblies is supported by a recent study, which showed that binding of α-synuclein PFFs to the immunoglobulin surface protein lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3) followed by endosomal internalization, is a critical uptake mechanism in neurons (Mao et al. 2016). However, multiple uptake mechanisms may be at play since binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans have also been shown to mediate the internalization of aggregated α-synuclein via macropinocytosis (Holmes et al. 2013).

One potential mechanism by which intracellular α-synuclein aggregates may perturb cells is through the disruption of membrane function (Shrivastava et al. 2015), permeability (Lashuel et al. 2002), or fusion, especially in the endosomal and vesicular pathways. The latter mechanism has been extensively investigated in yeast cells, which are heavily dependent on endocytic and secretory pathways (Outeiro and Lindquist 2003). Overexpression of α-synuclein in this model system results in dose-dependent toxicity, accumulation of vacuoles, and aggregation with several Rab GTPases (Gitler et al. 2008; Soper et al. 2008, 2011). In addition, α-synuclein interacts with prenylated Rab acceptor protein (PRA1) (Lee et al. 2011) found in the Golgi and late endosomes and regulates the cycling of Rab GTPases during exocytosis and endocytosis (Abdul-Ghani et al. 2001). Co-transfection of α-synuclein and PRA1 caused defects in vesicle trafficking, possibly by inhibition of Rab recycling (Lee et al. 2011). Fusion of late endosomes with lysosomes or autophagosomes requires the SNARE complex (Nichols and Pelham 1998), which is also important for synaptic vesicle fusion. α-Synuclein has been reported to bind to the SNARE protein synaptobrevin-2 (VAMP2) and is required for SNARE complex assembly at the synapse (Burré et al. 2010, 2014). Endogenous α-synuclein was protective against neurodegeneration caused by deletion of the SNARE chaperone cysteine-string protein α (CSPα) (Chandra et al. 2005), whereas its overexpression in Tg mouse models caused redistribution of SNARE proteins (Garcia-Reitböck et al. 2010; Lim et al. 2011). Addition of PFFs to primary neuronal cultures triggered the accumulation of endogenous α-synuclein in axons and impaired Rab7-positive endosomal transport and fusion with lysosomes (Volpicelli-Daley et al. 2014).

Given that aggregated α-synuclein is readily taken up by a variety of cells, including neurons, and can seed aggregation of expressed α-synuclein, it is likely that defense mechanisms exist that prevent the accumulation of α-synuclein and/or rapidly target misfolded α-synuclein for destruction. Although α-synuclein is degraded by both proteasomes and lysosomes, the latter have emerged as the most relevant degradative pathway in PD pathomechanisms (reviewed in Tofaris 2012). Delivery to lysosomes occurs by chaperone-mediated autophagy, macroautophagy, or the endosomal pathway. Autophagosomes also fuse with late endosomes to form amphisomes, indicating that these two routes to the lysosome are interconnected. Macroautophagy is the least selective process of lysosomal degradation, whereas chaperone-mediated autophagy is based on the recognition of a specific amino acid sequence (KFERQ), a motif found in nearly 30% of cytoplasmic proteins (Cuervo et al. 2004), by the heat shock cognate protein 70, triggering the translocation of the substrate through LAMP2A inside the lysosome (Nixon 2013). On the other hand, conjugation of a specific type of ubiquitin chain to protein substrates is a highly regulated process, which mediates trafficking of selective protein cargoes to lysosomes via the endosomal or autophagic pathway. This posttranslational modification occurs in a three-step catalytic process, involving a ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1, a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2, and a ubiquitin ligase E3. At the proteasome and during endosomal uptake, ubiquitin chains are disassembled by de-ubiquitinating enzymes so that the ubiquitin molecules can be reused in subsequent rounds of degradation, but this action of de-ubiquitinases can also serve to prevent the degradation of substrates. Correct delivery of individual protein substrates or protein complexes to lysosomes typically involves the conjugation of a polyubiquitin chain linked via lysine-63 (K63) or multiple monoubiquitins. This in turn triggers the assembly of a highly conserved machinery, the endosomal complex required for transport (ESCRT), which captures the ubiquitin conjugates on the endosomal membrane. ESCRT complexes comprise four distinct assemblies (ESCRT 0, I, II, or III), which recognize the cargo, associate with the endosomal membrane, and sort protein substrates in intraluminal vesicles (Raiborg and Stenmark 2009). Under certain conditions, which are not fully understood, K63-linked ubiquitin chains are also recognized by the autophagy receptors TAX1BP1, NDP52, NBR1, p62 (SQSTM1), and optineurin, which recruit LC3-coated phagophores to mediate a more selective autophagy.

Both macroautophagy (Webb et al. 2003) and chaperone-mediated autophagy (Cuervo et al. 2004) have been implicated in the lysosomal clearance of α-synuclein and the activation of autophagy in vivo was protective against α-synuclein overexpression (Decressac et al. 2013; Xilouri et al. 2013). α-Synuclein is also found within endosomes (Mak et al. 2010; Hasegawa et al. 2011; Boassa et al. 2013). Endosomal α-synuclein is either targeted for degradation by lysosomes or enters the recycling endosome and is released in a process involving Rab11a and Hsp90 (Liu et al. 2009; Hasegawa et al. 2011). Once delivered to the lysosome, α-synuclein is degraded primarily by cathepsin D (Sevlever et al. 2008), which, when overexpressed in vivo, was also protective against α-synuclein toxicity (Qiao et al. 2008; Cullen et al. 2009; Crabtree et al. 2014). Reduced expression of LAMP1 and cathepsin D was detected in nigral neurons with Lewy pathology (Chu et al. 2009). Importantly, heterozygous mutations in the lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase (GBA) increase the risk of PD by fivefold (Sidransky et al. 2009; Nalls et al. 2013), which is at least partly a result of decreased degradation and increased toxicity of aggregated α-synuclein (Mazzulli et al. 2011; Sardi et al. 2011; Schöndorf et al. 2014). Pharmacological chaperones that promote GBA stability and trafficking to the lysosome (Steet et al. 2006; Khanna et al. 2010) were effective in improving lysosomal function and in reducing α-synuclein levels in cellular models (McNeill et al. 2014) and in Tg mice overexpressing human α-synuclein, where they improved motor function (Richter et al. 2014). It has also been reported that heterozygous GBA mutations in iPSC-derived neurons (Fernandez et al. 2016), as well as autophagic or lysosomal inhibition in cell lines (Alvares-Elviri et al. 2011), enhances the extracellular release of α-synuclein, and that GBA deficiency in Tg animals promotes the cell-to-cell transfer of α-synuclein aggregates (Bae et al. 2014). Collectively, these data suggest that α-synuclein is trafficked to lysosomes for degradation and that inhibition of this process can exacerbate intra- and transneuronal α-synuclein toxicity because of raised protein levels and secretion.

Since a fraction of α-synuclein in Lewy pathology is ubiquitinated (Tofaris et al. 2003; Anderson et al. 2006), ubiquitin ligases may be relevant to its trafficking and turnover. Nedd4 (neuronally expressed developmentally downregulated gene 4) serves a critical function in the endosomal–lysosomal pathway, promoting the degradation of membrane-associated proteins (Rotin and Kumar 2009). Nedd4 is downregulated during development and upregulated in response to oxidative stress (Hoshikawa et al. 2003), traumatic head injury (Sang et al. 2006), and neurodegeneration (Kwak et al. 2012), indicating that its expression in neurons is tightly regulated. Nedd4 and its yeast ortholog Rsp5 ubiquitinate α-synuclein in vitro by recognizing its proline-rich C-terminus (Tofaris et al. 2011). This leads to the conjugation of uniform K63-linked ubiquitin chains on specific lysine residues of α-synuclein (Lys-21 and Lys-96). Interestingly, Lys-96 of α-synuclein has been identified as its primary ubiquitination site in rat brain by an antibody-based proteomic analysis (Na et al. 2012). In addition, K63-linked conjugates are present in Lewy bodies, and their abundance inversely correlates with the de-ubiquitinase Usp8, which opposes the lysosomal degradation of α-synuclein in mammalian cells by de-ubiquitination and modifies its toxicity in the Drosophila model (Alexopoulou et al. 2016). In mammalian cells, Nedd4 overexpression promoted the degradation of α-synuclein by the ESCRT-mediated endosomal-lysosomal route and, in yeast, Rsp5 protected against α-synuclein toxicity (Tofaris et al. 2011). More recently, it was shown that Nedd4 overexpression protects against α-synuclein accumulation in Drosophila and rat models of α-synucleinopathy, whereas endogenous Nedd4 in Drosophila is especially critical for the dopaminergic neuronal response to α-synuclein toxicity (Davies et al. 2014). Nedd4 is upregulated in a subpopulation of pigmented neurons containing Lewy pathology (Tofaris et al. 2011), and Nedd4 mRNA levels are increased in brain regions with Lewy pathology (Dumitriu et al. 2012). In agreement with these observations, a chemical genetic screen has identified a small molecule that binds to and activates Nedd4 as a neuroprotective agent in yeast and iPSC-derived cortical neuronal models of α-synuclein toxicity (Chung et al. 2013). That the ubiquitin ligase activity of Nedd4 and Rsp5 is necessary for neuroprotection, at least partly by a direct effect on α-synuclein (Tofaris et al. 2011; Davies et al. 2014), has been confirmed and extended by recent studies, which have shown that Nedd4 also promotes the endosomal processing of internalized α-synuclein (Sugeno et al. 2014) and have identified Rsp5 mutants in yeast that enhance α-synuclein ubiquitination and clearance (Wijayanti et al. 2014). Additionally, α-synuclein-independent protective effects are also possible. For example, Nedd4 promotes the ubiquitination and recycling of AMPA receptors at the synapse (Hou et al. 2011). AMPA receptors are also regulated, downstream from Nedd4, by the retromer (Munsie et al. 2014), which has been implicated in familial PD (Vilariño-Güell et al. 2011). In addition, Nedd4 has been shown to ubiquitinate cytosolic misfolded proteins following heat stress (Fang et al. 2014) and misfolded A53T mutant α-synuclein (Davies et al. 2014), suggesting that it may also promote the clearance of intracellular aggregates. Therefore, enzymes that function in endosomal trafficking directly regulate α-synuclein levels by ubiquitination and/or modify its toxicity in different model systems.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this review, we have highlighted recent advances suggesting that aggregated α-synuclein has prion-like properties. It can spread from cell to cell by uptake and release, templating further aggregation that eventually leads to damage and cell death. Recent studies have shown that both endogenous and internalized α-synuclein is processed via the endosomal route, suggesting that enzymes that regulate this trafficking step could serve as a nodal point in α-synuclein recycling; although such clearance pathways act primarily as disposal mechanisms via the lysosome, they could potentially be “hijacked” by aberrant conformers to promote pathogenicity under certain conditions. For example, ubiquitin-mediated endocytosis of α-synuclein-receptor complexes may regulate the translocation of misfolded α-synuclein assemblies in endosomes. These species could in turn interact with endogenously trafficked protein in endosomal compartments (early endosomes or multivesicular bodies), triggering template amplification (as shown in the proposed model in Fig. 1). Interestingly, oligomerization of α-synuclein has been shown to occur within vesicles (Jang et al. 2010). The low pH of vesicular compartments may reduce the negative charge of the C-terminus of α-synuclein, resulting in an increase in its hydrophobicity, which is more permissive for aggregation (Uversky et al. 2001; McClendon et al. 2009; Buell et al. 2014). Misfolded species could be released intracellularly because of membrane rupture (Freeman et al. 2013), acting as seeds for the aggregation of cytosolic α-synuclein or extracellularly via exocytosis and possibly exosome release. This would be reminiscent of Aβ and prions, where endosomal processing appears to be critical for the generation of the toxic species, as well as for physiological trafficking (Bohm et al. 2015; Goold et al. 2015). This also suggests that there may be a therapeutic window within which activation of such pathways is beneficial. Understanding these molecular events will clarify the therapeutic potential of enzymes that regulate protein trafficking and degradation in synucleinopathies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

G.K.T. is supported by a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellowship and the Wellcome-Beit award, the Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), the British Medical Association (BMA), and Alzheimer’s Research UK ARUK. M.G. is supported by the UK Medical Research Council (U105184291). M.G.S. is supported by the National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement & Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3R), ARUK, and the Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Footnotes

Editor: Stanley B. Prusiner

Additional Perspectives on Prion Diseases available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Abdul-Ghani M, Gougeon PY, Prosser DC, Da-Silva LF, Ngsee JK. 2001. PRA isoforms are targeted to distinct membrane compartments. J Biol Chem 276: 6225–6233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulou Z, Lang J, Perrett RM, Elschami M, Hurry ME, Kim HT, Mazaraki D, Szabo A, Kessler BM, Goldberg AL, et al. 2006. Deubiquitinase Usp8 regulates α-synuclein clearance and motifies its toxicity in Lewy body disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113: E4688–E4697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Schapira AH, Gardiner C, Sargent IL, Wood MJ, Cooper JM. 2011. Lysosomal dysfunction increases exosome-mediated α-synuclein release and transmission. Neurobiol Dis 42: 360–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JP, Walker DE, Goldstein JM, de Laat R, Banducci K, Caccavello RJ, Barbour R, Huang J, Kling K, Lee M, et al. 2006. Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of α-synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J Biol Chem 281: 29739–29752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae EJ, Yang NY, Song M, Lee CS, Lee JS, Jung BC, Lee HJ, Kim S, Masliah E, Sardi SP, et al. 2014. Glucocerebrosidase depletion enhances cell-to-cell transmission of α-synuclein. Nat Commun 5: 4755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boassa D, Berlanga ML, Yang MA, Terada M, Hu J, Bushong EA, Hwang M, Masliah E, George JM, Ellisman MH. 2013. Mapping the subcellular distribution of α-synuclein in neurons using genetically encoded probes for correlated light and electron microscopy: Implications for Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. J Neurosci 33: 2605–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm C, Chen F, Sevalle J, Qamar S, Dodd R, Li Y, Schmitt-Ulms G, Fraser PE, St George-Hyslop PH. 2015. Current and future implications of basic and translational amyloid-β peptide production and removal pathways. Mol Cell Neurosci 60: 3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousset L, Pieri L, Ruiz-Arlandis G, Gath J, Jensen PH, Habenstein B, Madiona K, Olieric V, Böckmann A, Meier BH, et al. 2013. Structural and functional characterization of two α-synuclein strains. Nat Commun 4: 2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. 2003. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 24: 197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breda C, Nugent ML, Estranero JG, Kyriacou CP, Outeiro TF, Steinert JR, Giorgini F. 2015. Rab11 modulates α-synuclein-mediated defects in synaptic transmission and behaviour. Hum Mol Genet 24: 1077–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buell AK, Galvagnion C, Gaspar R, Sparr E, Vendruscolo M, Knowles TP, Linse S, Dobson CM. 2014. Solution conditions determine the relative importance of nucleation and growth processes in α-synuclein aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: 7671–7676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burré J, Sharma M, Tsetsenis T, Buchman V, Etherton MR, Südhof TC. 2010. α-Synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science 329: 1663–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burré J, Sharma M, Südhof TC. 2014. α-Synuclein assembles into higher-order multimers upon membrane binding to promote SNARE complex formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: E4274–E4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Gallardo G, Fernández-Chacón R, Schlüter OM, Südhof TC. 2005. α-Synuclein cooperates with CSPα in preventing neurodegeneration. Cell 123: 383–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi W, Zibaee S, Jakes R, Serpell LC, Davletov B, Crowther RA, Goedert M. 2004. Mutation E46K increases phospholipid binding and assembly into filaments of human α-synuclein. FEBS Lett 576: 363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y, Dodiya H, Aebischer P, Olanow CW, Kordower JH. 2009. Alterations in lysosomal and proteasomal markers in Parkinson’s disease: Relationship to α-synuclein inclusions. Neurobiol Dis 35: 385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CY, Khurana V, Auluck PK, Tardiff DF, Mazzulli JR, Soldner F, Baru V, Lou Y, Freyzon Y, Cho S, et al. 2013. Identification and rescue of α-synuclein toxicity in Parkinson patient-derived neurons. Science 342: 983–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KA, Harper JD, Lansbury PT. 1998. Accelerated in vitro fibril formation by a mutant α-synuclein linked to early-onset Parkinson disease. Nat Med 4: 1318–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree D, Dodson M, Ouyang X, Boyer-Guittaut M, Liang Q, Ballestas ME, Fineberg N, Zhang J. 2014. Over-expression of an inactive mutant cathepsin D increases endogenous α-synuclein and cathepsin B activity in SH-SY5Y cells. J Neurochem 128: 950–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, Sulzer D. 2004. Impaired degradation of mutant α-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Science 305: 1292–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen V, Lindfors M, Ng J, Paetau A, Swinton E, Kolodziej P, Boston H, Saftig P, Woulfe J, Feany MB, et al. 2009. Cathepsin D expression level affects α-synuclein processing, aggregation, and toxicity in vivo. Mol Brain 2: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzer KM, Ruf WP, Putcha P, Joyner D, Hashimoto T, Glabe C, Hyman BT, McLean PJ. 2011. Heat-shock protein 70 modulates toxic extracellular α-synuclein oligomers and rescues trans-synaptic toxicity. FASEB J 25: 326–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SE, Hallett PJ, Moens T, Smith G, Mangano E, Kim HT, Goldberg AL, Liu JL, Isacson O, Tofaris GK. 2014. Enhanced ubiquitin-dependent degradation by Nedd4 protects against α-synuclein accumulation and toxicity in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 64: 79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decressac M, Mattsson B, Weikop P, Lundblad M, Jakobsson J, Björklund A. 2013. TFEB-mediated autophagy rescues midbrain dopamine neurons from α-synuclein toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: E1817–E1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer U, Selkoe D, Bartels T. 2015. New insights into cellular α-synuclein homeostasis in health and disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol 36: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplats P, Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Patrick C, Rockenstein E, Crews L, Spencer B, Masliah E, Lee SJ. 2009. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of α-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 13010–13015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitriu A, Latourelle JC, Hadzi TC, Pankratz N, Garza D, Miller JP, Vance JM, Foroud T, Beach TG, Myers RH. 2012. Gene expression profiles in Parkinson disease prefrontal cortex implicate FOXO1 and genes under its transcriptional regulation. PLoS Genet 8: e1002794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Agnaf OM, Salem SA, Paleologou KE, Cooper LJ, Fullwood NJ, Gibson MJ, Curran MD, Court JA, Mann DM, Ikeda S, et al. 2003. α-Synuclein implicated in Parkinson’s disease is present in extracellular biological fluids, including human plasma. FASEB J 17: 1945–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidou E, Melachroinou K, Roumeliotis T, Garbis SD, Ntzouni M, Margaritis LH, Stefanis L, Vekrellis K. 2010. Cell-produced α-synuclein is secreted in a calcium-dependent manner by exosomes and impacts neuronal survival. J Neurosci 30: 6838–6851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang NN, Chan GT, Zhu M, Comyn SA, Persaud A, Deshaies RJ, Rotin D, Gsponer J, Mayor T. 2014. Rsp5/Nedd4 is the main ubiquitin ligase that targets cytosolic misfolded proteins following heat stress. Nat Cell Biol 16: 1227–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares MB, Ait-Bouziad N, Dikiy I, Mbefo MK, Jovičić A, Kiely A, Holton JL, Lee SJ, Gitler AD, Eliezer D, et al. 2014. The novel Parkinson’s disease linked mutation G51D attenuates in vitro aggregation and membrane binding of α-synuclein, and enhances its secretion and nuclear localization in cells. Hum Mol Genet 23: 4491–4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feany MB, Bender WW. 2000. A Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Nature 404: 394–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes HJ, Hartfield EM, Christian HC, Emmanoulidou E, Zheng Y, Booth H, Bogetofte H, Lang C, Ryan BJ, Sardi SP, et al. 2016. ER stress and autophagic perturbations lead to elevated extracellular α-synuclein in GBA-N370S Parkinson’s iPSC-derived dopamine neurons. Stem Cell Rep 6: 342–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D, Cedillos R, Choyke S, Lukic Z, McGuire K, Marvin S, Burrage AM, Sudholt S, Rana A, O’Connor C, et al. 2013. α-Synuclein induces lysosomal rupture and cathepsin dependent reactive oxygen species following endocytosis. PLoS ONE 8: e62143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freundt EC, Maynard N, Clancy EK, Roy S, Bousset L, Sourigues Y, Covert M, Melki R, Kirkegaard K, Brahic M. 2012. Neuron-to-neuron transmission of α-synuclein fibrils through axonal transport. Ann Neurol 72: 517–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Reitböck P, Anichtchik O, Bellucci A, Iovino M, Ballini C, Fineberg E, Ghetti B, Della Corte L, Spano P, Tofaris GK, et al. 2010. SNARE protein redistribution and synaptic failure in a transgenic mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain 133: 2032–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D, Mondal M, Mohite GM, Singh PK, Ranjan P, Anoop A, Ghosh S, Jha NN, Kumar A, Maji SK. 2013. The Parkinson’s disease-associated H50Q mutation accelerates α-synuclein aggregation in vitro. Biochemistry 52: 6925–6927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D, Sahay S, Ranjan P, Salot S, Mohite GM, Singh PK, Dwivedi S, Carvalho E, Banerjee R, Kumar A, et al. 2014. The newly discovered Parkinson’s disease associated Finnish mutation (A53E) attenuates α-synuclein aggregation and membrane binding. Biochemistry 53: 6419–6421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giasson BI, Murray IV, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. 2001. A hydrophobic stretch of 12 amino acid residues in the middle of α-synuclein is essential for filament assembly. J Biol Chem 276: 2380–2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler AD, Bevis BJ, Shorter J, Strathearn KE, Hamamichi S, Su LJ, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Rochet JC, McCaffery JM, et al. 2008. The Parkinson’s disease protein α-synuclein disrupts cellular Rab homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 145–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M. 2015. Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: The prion concept in relation to assembled Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein. Science 349: 1255555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Del Tredici K, Braak H. 2013. 100 years of Lewy payhology. Nat Rev Neurol 9: 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goold R, McKinnon C, Tabrizi SJ. 2015. Prion degradation pathways: Potential for therapeutic intervention. Mol Cell Neurosci 66: 12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MT, Munoz DG, Schlossmacher MG, Gray DA, Woulfe JM. 2015. Protective effect of vagotomy suggests source organ for Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 78: 834–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum EA, Graves CL, Mishizen-Eberz AJ, Lupoli MA, Lynch DR, Englander SW, Axelsen PH, Giasson BI. 2005. The E46K mutation in α-synuclein increases amyloid fibril formation. J Biol Chem 280: 7800–7807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen C, Angot E, Bergström AL, Steiner JA, Pieri L, Paul G, Outeiro TF, Melki R, Kallunki P, Fog K, et al. 2011. α-Synuclein propagates from mouse brain to grafted dopaminergic neurons and seeds aggregation in cultured human cells. J Clin Invest 121: 715–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T, Konno M, Baba T, Sugeno N, Kikuchi A, Kobayashi M, Miura E, Tanaka N, Tamai K, Furukawa K, et al. 2011. The AAA-ATPase VPS4 regulates extracellular secretion and lysosomal targeting of α-synuclein. PLoS ONE 6: e29460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hely MA, Reid WG, Adena MA, Halliday GM, Morris JG. 2008. The Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson’s disease: The inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov Disord 23: 837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes BB, DeVos SL, Kfoury N, Li M, Jacks R, Yanamandra K, Ouidja MO, Brodsky FM, Marasa J, Bagchi DP, et al. 2013. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate internalization and propagation of specific proteopathic seeds. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: E3138–E3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist S, Chutna O, Bousset L, Aldrin-Kirk P, Li W, Björklund T, Wang ZY, Roybon L, Melki R, Li JY. 2014. Direct evidence of Parkinson pathology spread from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain in rats. Acta Neuropathol 128: 805–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshikawa C, Shichiri M, Nakamori S, Takagi H. 2003. A nonconserved Ala401 in the yeast Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase is involved in degradation of Gap1 permease and stress-induced abnormal proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 11505–11510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Q, Gilbert J, Man HY. 2011. Homeostatic regulation of AMPA receptor trafficking and degradation by light-controlled single-synaptic activation. Neuron 72: 806–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang A, Lee HJ, Suk JE, Jung JW, Kim KP, Lee SJ. 2010. Non-classical exocytosis of α-synuclein is sensitive to folding states and promoted under stress conditions. J Neurochem 113: 1263–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PH, Nielsen MS, Jakes R, Dotti CG, Goedert M. 1998. Binding of α-synuclein to brain vesicles is abolished by familial Parkinson’s disease mutation. J Biol Chem 273: 26292–26294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Benjamin ER, Pellegrino L, Schilling A, Rigat BA, Soska R, Nafar H, Ranes BE, Feng J, Lun Y, et al. 2010. The pharmacological chaperone isofagomine increases the activity of the Gaucher disease L444P mutant form of β-glucosidase. FEBS J 277: 1618–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Freeman TB, Olanow CW. 2008. Lewy body-like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Med 14: 504–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak YD, Wang B, Li JJ, Wang R, Deng Q, Diao S, Chen Y, Xu R, Masliah E, Xu H, et al. 2012. Upregulation of the E3 ligase NEDD4-1 by oxidative stress degrades IGF-1 receptor protein in neurodegeneration. J Neurosci 32: 10971–10981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashuel HA, Hartley D, Petre BM, Walz T, Lansbury PT Jr. 2002. Neurodegenerative disease: Amyloid pores from pathogenic mutations. Nature 418: 291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Patel S, Lee SJ. 2005. Intravesicular localization and exocytosis of α-synuclein and its aggregates. J Neurosci 25: 6016–6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Kang SJ, Lee K, Im H. 2011. Human α-synuclein modulates vesicle trafficking through its interaction with prenylated Rab acceptor protein 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 412: 526–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Lee SJ. 2014. Extracellular α-synuclein—A novel and crucial factor in Lewy body diseases. Nat Rev Neurol 10: 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. 2009. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 373: 2055–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Uversky VN, Fink AL. 2001. Effect of familial Parkinson’s disease point mutations A30P and A53T on the structural properties, aggregation, and fibrillation of human α-synuclein. Biochemistry 40: 11604–11613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Englund E, Holton JL, Soulet D, Hagell P, Lees AJ, Lashley T, Quinn NP, Rehncrona S, Björklund A, et al. 2008. Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson’s disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation. Nat Med 14: 501–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Y, Kehm VM, Lee EB, Soper JH, Li C, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. 2011. α-Syn suppression reverses synaptic and memory defects in a mouse model of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurosci 31: 10076–10087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhang JP, Shi M, Quinn T, Bradner J, Beyer R, Chen S, Zhang J. 2009. Rab11a and HSP90 regulate recycling of extracellular α-synuclein. J Neurosci 29: 1480–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk KC, Kehm V, Carroll J, Zhang B, O’Brien P, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. 2012. Pathological α-synuclein transmission initiates Parkinson-like neurodegeneration in nontransgenic mice. Science 338: 949–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak SK, McCormack AL, Manning-Bog AB, Cuervo AM, Di Monte DA. 2010. Lysosomal degradation of α-synuclein in vivo. J Biol Chem 285: 13621–13629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Ou MT, Karuppagounder SS, Kam T-I, Yin X, Xiong Y, Ge P, Umanah GE, Brahmachari S, Shin J-H. 2016. Pathological α-synuclein transmission initiated by binding lymphocyte-activation gene 3. Science 353: piiaah3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda-Suzukake M, Nonaka T, Hosokawa M, Oikawa T, Arai T, Akiyama H, Mann DM, Hasegawa M. 2013. Prion-like spreading of pathological α-synuclein in brain. Brain 136: 1128–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzulli JR, Xu YH, Sun Y, Knight AL, McLean PJ, Caldwell GA, Sidransky E, Grabowski GA, Krainc D. 2011. Gaucher disease glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein form a bidirectional pathogenic loop in synucleinopathies. Cell 146: 37–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClendon S, Rospigliosi CC, Eliezer D. 2009. Charge neutralization and collapse of the C-terminal tail of α-synuclein at low pH. Protein Sci 18: 1531–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill A, Magalhaes J, Shen C, Chau KY, Hughes D, Mehta A, Foltynie T, Cooper JM, Abramov AY, Gegg M, et al. 2014. Ambroxol improves lysosomal biochemistry in glucocerebrosidase mutation-linked Parkinson disease cells. Brain 137: 1481–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougenot AL, Nicot S, Bencsik A, Morignat E, Verchère J, Lakhdar L, Legastelois S, Baron T. 2012. Prion-like acceleration of a synucleinopathy in a transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol Aging 33: 2225–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsie LN, Milnerwood AJ, Seibler P, Beccano-Kelly DA, Tatarnikov I, Khinda J, Volta M, Kadgien C, Cao LP, Tapia L, et al. 2014. Retromer-dependent neurotransmitter receptor trafficking to synapses is altered by the Parkinson’s disease VPS35 mutation p.D620N. Hum Mol Genet 24: 1691–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na CH, Jones DR, Yang Y, Wang X, Xu Y, Peng J. 2012. Synaptic protein ubiquitination in rat brain revealed by antibody-based ubiquitome analysis. J Proteome Res 11: 4722–4732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalls MA, Duran R, Lopez G, Kurzawa-Akanbi M, McKeith IG, Chinnery PF, Morris CM, Theuns J, Crosiers D, Cras P. 2013. A multicenter study of glucocerebrosidase mutations in dementia with Lewy bodies. JAMA Neurol 70: 727–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols BJ, Pelham HR. 1998. SNAREs and membrane fusion in the Golgi apparatus. Biochim Biophys Acta 1404: 9–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA. 2013. The role of autophagy in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med 19: 983–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterberg VR, Spinelli KJ, Weston LJ, Luk KC, Woltjer RL, Unni VK. 2015. Progressive aggregation of α-synuclein and selective degeneration of Lewy inclusion-bearing neurons in a mouse model of parkinsonism. Cell Rep 10: 1252–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outeiro TF, Lindquist S. 2003. Yeast cells provide insight into α-synuclein biology and pathobiology. Science 302: 1772–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan-Montojo F, Anichtchik O, Dening Y, Knels L, Pursche S, Jung R, Jackson S, Gille G, Spillantini MG, Reichmann H, et al. 2010. Progression of Parkinson’s disease pathology is reproduced by intragastric administration of rotenone in mice. PLoS ONE 5: e8762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peelaerts W, Bousset L, Van der Perren A, Moskalyuk A, Pulizzi R, Giugliano M, Van den Haute C, Melki R, Baekelandt V. 2015. α-Synuclein strains cause distinct synucleinopathies after local and systemic administration. Nature 522: 340–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrett RM, Alexopoulou Z, Tofaris GK. 2015. The endosomal pathway in Parkinson’s disease. Mol Cell Neurosci 66: 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, et al. 1997. Mutation in the α-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science 276: 2045–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB, Woerman AL, Mordes DA, Watts JC, Rampersaud R, Berry DB, Patel S, Oehler A, Lowe JK, Kravitz SN, et al. 2015. Evidence for α-synuclein prions causing multiple system atrophy in humans with parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112: E5308–E5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao L, Hamamichi S, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Yacoubian TA, Wilson S, Xie ZL, Speake LD, Parks R, Crabtree D, et al. 2008. Lysosomal enzyme cathepsin D protects against α-synuclein aggregation and toxicity. Mol Brain 1: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C, Stenmark H. 2009. The ESCRT machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins. Nature 458: 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recasens A, Dehay B, Bové J, Carballo-Carbajal I, Dovero S, Pérez-Villalba A, Fernagut PO, Blesa J, Parent A, Perier C, et al. 2014. Lewy body extracts from Parkinson disease brains trigger α-synuclein pathology and neurodegeneration in mice and monkeys. Ann Neurol 275: 351–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter F, Fleming SM, Watson M, Lemesre V, Pellegrino L, Ranes B, Zhu C, Mortazavi F, Mulligan CK, Sioshansi PC, et al. 2014. A GCase chaperone improves motor function in a mouse model of synucleinopathy. Neurotherapeutics 11: 840–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotin D, Kumar S. 2009. Physiological functions of the HECT family of ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 398–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacino AN, Brooks M, Thomas MA, McKinney AB, Lee S, Regenhardt RW, McGarvey NH, Ayers JI, Notterpek L, Borchelt DR, et al. 2013. Intramuscular injection of α-synuclein induces CNS α-synuclein pathology and a rapid-onset motor phenotype in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: 10732–10737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang Q, Kim MH, Kumar S, Bye N, Morganti-Kossman MC, Gunnersen J, Fuller S, Howitt J, Hyde L, Beissbarth T, et al. 2006. Nedd4-WW domain-binding protein 5 (Ndfip1) is associated with neuronal survival after acute cortical brain injury. J Neurosci 26: 7234–7244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardi SP, Clarke J, Kinnecom C, Tamsett TJ, Li L, Stanek LM, Passini MA, Grabowski GA, Schlossmacher MG, Sidman RL, et al. 2011. CNS expression of glucocerebrosidase corrects α-synuclein pathology and memory in a mouse model of Gaucher-related synucleinopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 12101–12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöndorf DC, Aureli M, McAllister FE, Hindley CJ, Mayer F, Schmid B, Sardi SP, Valsecchi M, Hoffmann S, Schwarz LK, et al. 2014. iPSC-derived neurons from GBA1-associated Parkinson’s disease patients show autophagic defects and impaired calcium homeostasis. Nat Commun 5: 4028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevlever D, Jiang P, Yen SH. 2008. Cathepsin D is the main lysosomal enzyme involved in the degradation of α-synuclein and generation of its carboxy-terminally truncated species. Biochemistry 47: 9678–9687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava AN, Redeker V, Fritz N, Pieri L, Almeida LG, Spolidoro M, Liebmann T, Bousset L, Renner M, Léna C, et al. 2015. α-Synuclein assemblies sequester neuronal α3-Na+/K+-ATPase and impair Na+ gradient. EMBO J 34: 2408–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidransky E, Nalls MA, Aasly JO, Aharon-Peretz J, Annesi G, Barbosa ER, Bar-Shira A, Berg D, Bras J, Brice A, et al. 2009. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 361: 1651–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper JH, Roy S, Stieber A, Lee E, Wilson RB, Trojanowski JQ, Burd CG, Lee VM. 2008. α-Synuclein-induced aggregation of cytoplasmic vesicles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 19: 1093–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper JH, Kehm V, Burd CG, Bankaitis VA, Lee VM. 2011. Aggregation of α-synuclein in S. cerevisiae is associated with defects in endosomal trafficking and phospholipid biosynthesis. J Mol Neurosci 43: 391–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. 1997. α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388: 839–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M. 1998a. α-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 6469–6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Cairns NJ, Lantos PL, Goedert M. 1998b. Filamentous α-synuclein inclusions link multiple system atrophy with Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurosci Lett 251: 205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steet RA, Chung S, Wustman B, Powe A, Do H, Kornfeld SA. 2006. The iminosugar isofagomine increases the activity of N370S mutant acid β-glucosidase in Gaucher fibroblasts by several mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 13813–13818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugeno N, Hasegawa T, Tanaka N, Fukuda M, Wakabayashi K, Oshima R, Konno M, Miura E, Kikuchi A, Baba T, et al. 2014. Lys-63-linked ubiquitination by E3 ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-1 facilitates endosomal sequestration of internalized α-synuclein. J Biol Chem 289: 18137–18151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung JY, Kim J, Paik SR, Park JH, Ahn YS, Chung KC. 2001. Induction of neuronal cell death by Rab5A-dependent endocytosis of α-synuclein. J Biol Chem 276: 27441–27448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanik SA, Schultheiss CE, Volpicelli-Daley LA, Brunden KR, Lee VM. 2013. Lewy body-like α-synuclein aggregates resist degradation and impair macroautophagy. J Biol Chem 288: 15194–15210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofaris GK. 2012. Lysosome-dependent pathways as a unifying theme in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 27: 1364–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofaris GK, Spillantini MG. 2007. Physiological and pathological properties of α-synuclein. Cell Mol Life Sci 64: 2194–2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofaris GK, Razzaq A, Ghetti B, Lilley KS, Spillantini MG. 2003. Ubiquitination of α-synuclein in Lewy bodies is a pathological event not associated with impairment of proteasome function. J Biol Chem 278: 44405–44411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofaris GK, Kim HT, Hourez R, Jung JW, Kim KP, Goldberg AL. 2011. Ubiquitin ligase Nedd4 promotes α-synuclein degradation by the endosomal-lysosomal pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 17004–17009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky VN, Li J, Fink AL. 2001. Evidence for a partially folded intermediate in α-synuclein fibril formation. J Biol Chem 276: 10737–10744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilariño-Güell C, Wider C, Ross OA, Dachsel JC, Kachergus JM, Lincoln SJ, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Cobb SA, Wilhoite GJ, Bacon JA, et al. 2011. VPS35 mutations in Parkinson disease. Am J Hum Genet 89: 162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli-Daley LA, Gamble KL, Schultheiss CE, Riddle DM, West AB, Lee VM. 2014. Formation of α-synuclein Lewy neurite-like aggregates in axons impedes the transport of distinct endosomes. Mol Biol Cell 25: 4010–4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts JC, Giles K, Oehler A, Middleton L, Dexter DT, Gentleman SM, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. 2013. Transmission of multiple system atrophy prions to transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 19555–19560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb JL, Ravikumar B, Atkins J, Skepper JN, Rubinsztein DC. 2003. α-Synuclein is degraded by both autophagy and the proteasome. J Biol Chem 278: 25009–25013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijayanti I, Watanabe D, Oshiro S, Takagi H. 2014. Isolation and functional analysis of yeast ubiquitin ligase Rsp5 variants that alleviate the toxicity of human α-synuclein. J Biochem 157: 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xilouri M, Brekk OR, Landeck N, Pitychoutis PM, Papasilekas T, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z, Kirik D, Stefanis L. 2013. Boosting chaperone-mediated autophagy in vivo mitigates α-synuclein-induced neurodegeneration. Brain 136: 2130–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]