Abstract

Objective:

The aim of the present review is to give an overview about the role, biosynthesis, and characteristics of Podophyllotoxin (PTOX) as a potential antitumor agent with particular emphasis on key biosynthesis processes, function of related enzymes and characterization of genes encoding the enzymes.

Materials and Methods:

Google scholar, PubMed and Scopus were searched for literatures which have studied identification, characterization, fermentation and therapeutic effects of PTOX and published in English language until end of 2016.

Results:

PTOX is an important plant-derived natural product, has derivatives such as etoposide and teniposide, which have been used as therapies for cancers and venereal wart. PTOX structure is closely related to the aryltetralin lactone lignans that have antineoplastic and antiviral activities. Podophyllum emodi Wall. (syn. P. hexandrum) and Podophyllum peltatum L. (Berberidaceae) are the major sources of PTOX. It has been shown that ferulic acid and methylenedioxy substituted cinnamic acid are the enzymes involved in PTOX synthesis. PTOX prevents cell growth via polymerization of tubulin, leading to cell cycle arrest and suppression of the formation of the mitotic-spindles microtubules.

Conclusion:

Several investigations have been performed in biosynthesis of PTOX such as cultivation of these plants, though they were unsuccessful. Thus, it is important to find alternative sources to satisfy the pharmaceutical demand for PTOX. Moreover, further preclinical studies are warranted to explore the molecular mechanisms of these agents in treatment of cancer and their possible potential to overcome chemoresistance of tumor cells.

Key Words: Podophyllotoxin, Anticancer, Antitumor, Natural products, Lignans

Introduction

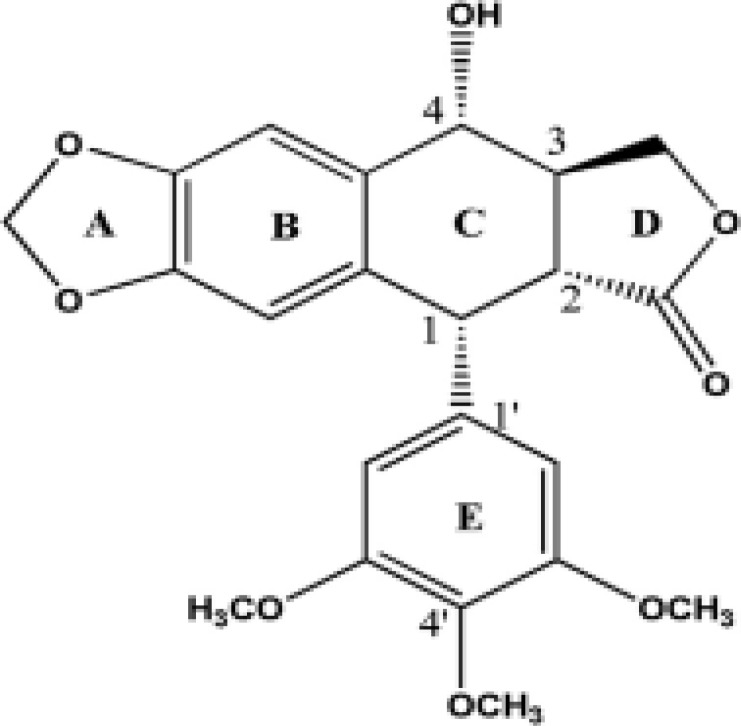

Extensive drug discovery and small molecules screening programs over the past thirty years, have presented plants and micro-organisms as rich sources of structurally diverse and highly bioactive natural products. One of the most important natural products are aryltetralin lactone lignans. Lignans are a family of natural products which are secondary metabolites produced through the shikimic acid pathway. The chemical structure of lignans is composed of two phenylpropane units and has a variety of skeletons and chemical characteristics; lignans can be divided into four groups: Lignans, Neolignans, Trimers and Oxyneolignans, higher analogues and mixed Lignanoids (Luo et al., 2014 ▶). It has been reported that natural aryltetralin lactone lignans are present in the plants of the families Cupressaceae, Berberidaceae, Apiaceae, Burseraceae, Verbenaceae, etc. Podophyllotoxin (PTOX) (C22H22O8) is an exclusive lignan because one of its derivatives was recognized as a potent antitumor factor (Figure 1) (Liu et al., 2015 ▶). Among the lignans, cyclolignans present a carbocycle between the two phenylpropane units, attached by two single carbon-carbon bonds through the side chains and one of them is between the β-βʹ positions. The aryltetralin structure of PTOX belongs to cyclolignans (Gordaliza et al., 2004 ▶). PTOX was first isolated in 1880 by Podwyssotzki from the North American plant Podophyllum peltatum L., commonly known as the American mandrake or May apple. This natural product has been also isolated from Podophyllum emodi (Indian podophyllum) (Ramos et al., 2001 ▶). It is particularly noticeable that PTOX is the most abundant lignan in podophyllin, a resin produced by species of the genus Podophyllum and some endophytic microorganisms in Cupressaceae family (Kusari et al., 2011 ▶). Despite extensive efforts done to propose new natural products for cancer therapy, a very small number of agents have been reached clinical practice. This can be explained at least in part by lack of enough knowledge about the molecular mechanisms of their action and possible side effects of these natural agents. Thus, the aim of current review is to give an overview about the role, biosynthesis, structure and spectral characteristics of aryltetralin lactone lignans as a potential antitumor agent.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of podophyllotoxin

PTOX: origin and sources

Lignans have been found in a large number of species, which are belonged to more than 60 families of vascular plants. Lignans can be isolated from different part of plants: roots and rhizomes, woody parts, stems, leaves, fruits, seeds and, in other cases, from endophytic microorganisms (Kusari et al., 2009 ▶; Schulz et al., 2002 ▶). Lignans have also been found in the urine of humans and mammals, although some of them are identical to components of the plant primary metabolites. Additionally, several distinct chemical reactions have been suggested, such as internal metabolic transformation (Zhang et al., 2014 ▶). It is important to mention that Podophyllum genus is not the only natural source of PTOX. This plant genus and other genera such as Jeffersonia, Diphylleia and Dysosma (Berberidaceae), Catharanthus (Apocynaceae), Polygala (Polygalaceae), Anthriscus (Apiaceae), Linun (Linaceae), Hyptis (Verbenaceae), Teucrium, Nepeta and Thymus (Labiaceae), Thuja, Juniperus, Callitris and Thujopsis (Cupressaceae), Cassia (Fabaceae), Haplophyllum (Rutaceae), Commiphora (Burseraceae), Hernandia (Hernandiaceae) can produce PTOX and derivatives (Table 1) (Kusari et al., 2011 ▶; Lim et al., 2007 ▶; Soltani and Moghaddam, 2015 ▶; Suzuki et al., 2002 ▶; Wink, 2012 ▶). However, environmental effects and difficulties in cultivation are the most marked problems in extraction of PTOX from plants (Dhar et al., 2002 ▶).

Table 1.

The list of natural sources of PTOX reported in the literature (1996 – 2015).

| No. | Gander | Species | Family name | Part | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant | Anthriscus sylvestris L. | Apiaceae | Root | (Jeong et al., 2007; Koulman et al., 2003) | |

| Dysosma versipllis | Berberidaceae | Root | (Yu et al., 1991) | ||

| Podophyllum hexandrum | Berberidaceae | Root | (Chattopadhyay et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2015) | ||

| Podophyllum versipelle Hance. | Berberidaceae | Root | (Broomhead and Dewick, 1990b) | ||

| Sinopodophyllum emodi | Berberidaceae | Leaf - Root | (Liang et al., 2015) | ||

| Juniperus sabina L. | Cupressaceae | Leaf | (San Feliciano et al., 1989a) | ||

| Juniperus thurifera L. | Cupressaceae | Leaf | (San Feliciano et al., 1989b) | ||

| Juniperus virginiana L. | Cupressaceae | Leaf | (Kupchan et al., 1965) | ||

| Juniperus chinensis L. | Cupressaceae | Root - Leaf | (Miyata et al., 1998; Muranaka et al., 1998) | ||

| Callitris intratropica | Cupressaceae | Root - Leaf | (Wanner et al., 2015) | ||

| Juniperus horizontalis Moench | Cupressaceae | Leaf | (Cantrell et al., 2014) | ||

| Juniperus scopulorum Sarg. | Cupressaceae | Leaf | (Cantrell et al., 2013) | ||

| Juniperus virginiana L. | Cupressaceae | Leaf | (Cushman et al., 2003) | ||

| Hyptis verticillata Jacq. | Lamiaceae | Root - Leaf | (Kuhnt et al., 1994) | ||

| Nepeta nudaI L. | Lamiaceae | Leaf - Root | (Konuklugil, 1996b) | ||

| Phlomis nissolii L. | Lamiaceae | Leaf - Root | (Konuklugil, 1996b; Loike, 1982) | ||

| Salvia cilicica Boiss. | Lamiaceae | Leaf - Root | (Konuklugil, 1996b) | ||

| Teucrium chamaedrys L. | Lamiaceae | Leaf - Root | (Konuklugil, 1996b) | ||

| Teucrium polium L. | Lamiaceae | Leaf - Root | (Konuklugil, 1996b) | ||

| Thymus capitatus H. | Lamiaceae | Leaf - Root | (Konuklugil, 1996b) | ||

| Linum album Kotschy ex Boiss. | Linaceae | Leaf - Root | (Chashmi et al., 2013; Yousefzadi et al., 2010) | ||

| Linum capitatum Kit. | Linaceae | Root - leaf | (Broomhead and Dewick, 1990a) | ||

| Linum flavum L. | Linaceae | Root - leaf | (Broomhead and Dewick, 1990a; Konuklugil, 1996a) | ||

| Linum thracicum | Linaceae | Root - Leaf | (Sasheva and Ionkova, 2015) | ||

| Linum mucronatum Gilib. | Linaceae | Root | (Samadi et al., 2014) | ||

| Polygala polygama Walter. | Polygalaceae | Leaf | (Petersen and Alfermann, 2001) | ||

| Fungi | Mucor fragilis | Mucoraceae | - | (Huang et al., 2014) | |

| Mucor fragilis | Mucoraceae | - | (Huang et al., 2014) | ||

| Fusarium oxysporum | Nectriaceae | - | (Kour et al., 2008) | ||

| Fusarium oxysporum | Nectriaceae | - | (Kour et al., 2008) | ||

| Fusarium solani | Nectriaceae | - | (Nadeem et al., 2012) | ||

| Trametes hirsuta | Polyporaceae | - | (Puri et al., 2006) | ||

| Trametes hirsuta | Polyporaceae | - | (Puri et al., 2006) | ||

| Piriformospora indica | Sebacinaceae | - | (Baldi et al., 2008) | ||

| Sebacina vermifera | Sebacinaceae | - | (Baldi et al., 2008) | ||

| Piriformospora indica | Sebacinaceae | - | (Baldi et al., 2008) | ||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Trichocomaceae | - | (Kusari et al., 2009) | ||

| Vibrisseaceae | - | (Eyberger et al., 2006) |

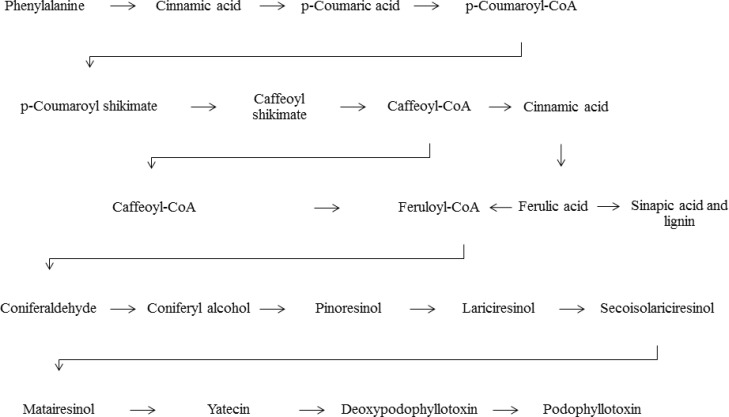

PTOX synthesis

The complete biosynthetic pathway of PTOX has not been recognized so far, but several studies on some species of Forsythia, Linum and Podophyllum have documented some procedures for synthesis of PTOX (Petersen and Alfermann, 2001 ▶). It has been illustrated that ferulic acid and methylenedioxy substituted cinnamic acid are key enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of PTOX (Figure 2) and other natural cyclolignans (Khaled et al., 2013 ▶; Seidel et al., 2002 ▶). In an in vitro experiment on Linum flavum L., 6-methoxypodophyllotoxin was found as the main cyclolignan, although this compound was not detected when the cells were cultured with PTOX. The results of this study showed that high affinity of kinetic constants reflects PTOX and PTOX can inhibit the production of 6-methoxypodophyllotoxin (Berim et al., 2008 ▶). Assessment of PTOX biosynthesis is a promising option which can help to discover novel sources and provide sustainable production of PTOX.

Figure 2.

Synthesis pathway of podophyllotoxin

Fermentation approach: a novel source of PTOX biosynthesis

Several attempts have been made to develop and identify an alternative way for the production of aryltetralin lignans especially PTOX, although little success has been achieved. Among these technologies, fermentation technology is reported as a promising approach (Kesting et al., 2009 ▶). Nowadays, several natural products are produced by microorganisms such as paclitaxel from Tubercularia sp. (Wang et al., 2000 ▶), anti-cancer pro-drug PTOX from Fusarium oxysporum (Dar et al., 2013 ▶; Kour et al., 2008 ▶; Kumar et al., 2013 ▶). Increasing evidence has shown that host-microbe systems such as symbiosis living between fungi and/or plants can produce PTOX (Aly et al., 2010 ▶; Puri et al., 2006 ▶), including biotransformations with whole cell fermentations (Giri and Narasu, 2000 ▶; Puri et al., 2006 ▶). The approach used Aspergillus fumigatus (Trichocomaceae), an endophytic fungus from Juniperus communis L. Horstmann (Cupressaceae), that can biosynthesize aryl tetralin lignans, including PTOX (Kusari et al., 2009 ▶).

Mechanism of action

There is growing body of evidence showing the potential anti-cancer activity of PTOX. It has been shown that PTOX has anti-neoplastic properties that prevent the assembly of tubulin into microtubules and persuading apoptosis (Abad et al., 2012 ▶). This effect can be achieved by preventing the polymerization of tubulin which thereby could induce cell cycle arrest at mitosis and impede the formation of the mitotic-spindles microtubules. This mechanism of action is comparable with an another alkaloid, colchicine (Passarella et al., 2010 ▶). The antitumor activity of PTOX against lung metastatic cancer has been reported (Utsugi et al., 1996 ▶). In this study, the inhibitory activity of etoposide and PTOX against topoisomerase II via induction of DNA strand breaks was shown (Utsugi et al., 1996 ▶). The results of preclinical studies showed that PTOX prevented the polymerization of microtubule resulting in mitotic detention as shown by accumulation of mitosis-related proteins, BIRC5 and aurora B (Chen et al., 2013 ▶). PTOX reversibly binds to tubulin, and interrupts the dynamic equipoise between the assembly and disassembly of microtubules, and finally causes mitotic arrest (Guerram et al., 2012 ▶). Moreover, it has been shown that semi-synthetic products of PTOX, such as etoposide, teniposide and etopophos, have an inhibitory activity on DNA topoisomerase II that prevents the re-ligation of DNA (Choi et al., 2015 ▶; Shin et al., 2010 ▶; Xu et al., 2009 ▶)

Pharmacological activity of PTOX

Several studies have shown the possible role of natural products in treatment of several disorders (Ardalani et al., 2016 ▶; Jandaghi et al., 2016 ▶) with different application to be used as antiviral, antifungal, antibacterial and anticancer agents. PTOX is suggested as an antiviral agent in the treatment of condyloma acuminatum caused by human papilloma virus (HPV) and other venereal warts (Wilson, 2002 ▶). In another in vitro study, podophyllotoxin derivatives showed promising cytotoxicities against a set of human cancer cell lines HL-60, A-549, HeLa, and HCT-8 (Liu et al., 2013 ▶). PTOX also activates pro-apoptotic endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling pathway. Intra-peritoneal injection of PTOX1 2 mg/kg significantly inhibited the growth of P-815, P-1537 and L-1210 tumor cells. The anti-tumor activity of this agent was more or less similar to that of paclitaxel (Wrasidlo et al., 2002 ▶). Also, the hematological and biochemical examinations showed that PTOX did not have organ toxicities in animal models (Chen et al., 2013 ▶). In a randomized clinical trial, the effects of PTOX on anogenital warts were compared with imiquimod 5% cream. The results showed a potent inhibitory effect on warts growth in PTOX-treated group vs. imiquimod cream-treated group (Komericki et al., 2011 ▶).

Pharmacokinetic of PTOX

In clinical studies, decreasing the absorption and the activity of a toxin in the living organism, is the major principles of poison management. Many clinical studies showed that dermal absorption of PTOX is limited and PTOX in body undergoes hepatic and renal metabolism (Lacey et al., 2003 ▶). In a study on anogenital warts, the topical application of 0.25 mg of PTOX was not associated with detectable serum concentrations of PTOX as measured by HPLC (Geo Von Krogh, 1982 ▶). Besides, it was found that the plasma concentration of PTOX, one hour after an intravenous injection of 3 mg/kg in rats, was indiscoverable and its excretion pathway is not clear yet (Deng et al., 1998 ▶).

Clinical trials of PTOX

The clinical trials on the use of PTOX and its derivatives against different sexual diseases, indicated that the use of this natural product could be effective on prevent and/or treatment of some cancer disorders. Most of clinical trials on PTOX were in treatment and control of genital warts and also the most effective time of treatment was 120 days (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical studies on PTOX and its derivatives

| No. | Type of medication | Duration of study | No. of patients | Disease | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cream and solution | 90 days | 358 | genital warts | (Lacey et al., 2003) |

| 2 | Cream and solution | 120 days | 109 | genital warts | (Beutner et al., 1989) |

| 3 | Cream | 90 days | 55 | external anogenital warts | (Arican et al., 2004) |

| 4 | Cream | 120 days | 311 | external anogenital warts | (Edwards et al., 1998) |

| 5 | Cream | 60 days | 108 | genital warts | (Beutner et al., 1998) |

| 6 | Solution | 30 days | 38 | penile warts | (Kirby et al., 1990) |

| 7 | Solution | 160 days | 57 | penile warts | (von Krogh et al., 1994) |

| 8 | Cream | 90 days | 60 | external genital condylomata acuminata | (Von Krogh and Hellberg, 1991) |

| 9 | Cream | 180 days | 150 | molluscum contagiosum | (Syed et al., 1994) |

Conclusion

The use of the secondary metabolites of plants or microorganisms has gained substantial attention in the treatment of cancer. PTOX is being suggested as a potential anticancer agent in treatment of tumor cells via preventing the polymerization of tubulin which induces cell cycle detention at mitosis and prevents cancer cells development. PTOX derivatives, such as etoposide and teniposide, have been suggested to be used as therapies for cancers and venereal wart. One of the main problems with this plant-derived natural product is its resources, which has led to studies to identify new sources, such as cultivation, plant cell or organ culture, and chemical synthesis. Therefore, understanding biosynthesis of PTOX is a key step for cultivation of medicinal plants. Indeed, we can use of microorganisms as an alternative source of PTOX. According to previous studies, synthesis of lignans in different microorganisms is not the same. Also, research on the synthesis pathways of PTOX in different microorganisms might be helpful to find the best source of this valuable lignin.

Acknowledgment

The author gratefully acknowledges the Vice Chancellor of Research, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

References

- Abad AS, López-Pérez JL, Del Olmo E, Garcia-Fernandez LF, Francesch AS, Trigili C, Barasoain I, Andreu JM, Díaz JF, San Feliciano A. Synthesis and antimitotic and tubulin interaction profiles of novel pinacol derivatives of podophyllotoxins. J Med Chem. 2012;55:6724–6737. doi: 10.1021/jm2017573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aly AH, Debbab A, Kjer J, Proksch P. Fungal endophytes from higher plants: a prolific source of phytochemicals and other bioactive natural products. Fungal Divers. 2010;41:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ardalani H, Hassanpour Moghadam M, Rahimi R, Soltani J, Mozayanimonfared A, Moradi M, Azizi A. Sumac as a novel adjunctive treatment in hypertension: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. RSC Adv. 2016;6:11507–11512. [Google Scholar]

- Arican O, Guneri F, Bilgic K, Karaoglu A. Topical Imiquimod 5% Cream in External Anogenital Warts: A Randomized, Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled Study. J Dermatol. 2004;31:627–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi A, Jain A, Gupta N, Srivastava A, Bisaria V. Co-culture of arbuscular mycorrhiza-like fungi (Piriformospora indica and Sebacina vermifera) with plant cells of Linum album for enhanced production of podophyllotoxins: a first report. Biotechnol Lett. 2008;30:1671–1677. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9736-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berim A, Ebel R, Schneider B, Petersen M. UDP-glucose:(6-methoxy) podophyllotoxin 7-O-glucosyltransferase from suspension cultures of Linum nodiflorum. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutner K, Friedman-Kien A, Artman N, Conant M, Illeman M, Thisted R, King D. Patient-applied podofilox for treatment of genital warts. Lancet. 1989;333:831–834. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutner KR, Spruance SL, Hougham AJ, Fox TL, Owens ML, Douglas JM. Treatment of genital warts with an immune-response modifier (imiquimod) J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:230–239. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broomhead AJ, Dewick PM. Aryltetralin lignans from Linum flavum and Linum capitatum. Phytochemistry. 1990a;29:3839–3844. [Google Scholar]

- Broomhead AJ, Dewick PM. Tumour-inhibitory aryltetralin lignans in Podophyllum versipelle, Diphylleia cymosa and Diphylleia grayi. Phytochemistry. 1990b;29:3831–3837. [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell CL, Zheljazkov VD, Carvalho CR, Astatkie T, Jeliazkova EA, Rosa LH. Dual extraction of essential oil and podophyllotoxin from creeping juniper (Juniperus horizontalis) Plos One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell CL, Zheljazkov VD, Osbrink WL, Castro A, Maddox V, Craker LE, Astatkie T. Podophyllotoxin and essential oil profile of Juniperus and related species. Ind Crop Prod. 2013;43:668–676. [Google Scholar]

- Chashmi NA, Sharifi M, Yousefzadi M, Behmanesh M, Rezadoost H, Cardillo A, Palazon J. Analysis of 6-methoxy podophyllotoxin and podophyllotoxin in hairy root cultures of Linum album Kotschy ex Boiss. Med Chem Res. 2013;22:745–752. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay S, Srivastava AK, Bhojwani SS, Bisaria VS. Production of podophyllotoxin by plant cell cultures of Podophyllum hexandrum in bioreactor. J Biosci Bioeng. 2002;93:215–220. doi: 10.1263/jbb.93.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, Tang YA, Li WS, Chiou YC, Shieh JM, Wang YC. A synthetic podophyllotoxin derivative exerts anti-cancer effects by inducing mitotic arrest and pro-apoptotic ER stress in lung cancer preclinical models. Plos One. 2013;8:e62082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JY, Cho HJ, Hwang SG, Kim WJ, Kim JI, Um HD, Park JK. Podophyllotoxin acetate enhances γ-ionizing radiation-induced apoptotic cell death by stimulating the ROS/p38/caspase pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;70:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman KE, Maqbool M, Gerard PD, Bedir E, Lata H, Moraes RM. Variation of podophyllotoxin in leaves of Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana) Planta Med. 2003;69:477–478. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar RA, Saba I, Shahnawaz M, Sangale MK, Ade AB, Rather SA, Qazi PH. Isolation, purification and characterization of carboxymethyl cellulase (CMCase) from endophytic Fusarium oxysporum producing podophyllotoxin. Adv Enz Res. 2013;1:91. [Google Scholar]

- Deng JF, Huang CC, Lee YJ. Toxicokinetic parameters in the management of poisoning: An example of podophylotoxin intoxication. J Toxicol Sci. 1998;23:205–208. doi: 10.2131/jts.23.supplementii_205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar U, Manjkhola S, Joshi M, Bhatt A, Bisht A, Joshi M. Current status and future strategy for development of medicinal plants sector in Uttaranchal, India. Cur Sci. 2002;83:956–964. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards L, Ferenczy A, Eron L, Baker D, Owens ML, Fox TL, Hougham AJ, Schmitt KA. Self-administered topical 5% imiquimod cream for external anogenital warts. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:25–30. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberger AL, Dondapati R, Porter JR. Endophyte fungal isolates from Podophyllum peltatum produce podophyllotoxin. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1121–1124. doi: 10.1021/np060174f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geo von krogh M. Podophyllotoxin in serum: absorption subsequent to three-day repeated applications of a 05% ethanolic preparation on condylomata acuminata. Sex Transm Dis. 1982;9:26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri A, Narasu ML. Production of podophyllotoxin from Podophyllum hexandrum: a potential natural product for clinically useful anticancer drugs. Cytotechnology. 2000;34:17–26. doi: 10.1023/A:1008138230896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordaliza M, Garcıa P, Del Corral JM, Castro M, Gomez-Zurita M. Podophyllotoxin: distribution, sources, applications and new cytotoxic derivatives. Toxicon. 2004;44:441–459. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerram M, Jiang ZZ, Zhang LY. Podophyllotoxin, a medicinal agent of plant origin: past, present and future. Chin J Nat Med. 2012;10:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Huang JX, Zhang J, Zhang XR, Zhang K, Zhang X, He XR. Mucor fragilis as a novel source of the key pharmaceutical agents podophyllotoxin and kaempferol. Pharm Biol. 2014;52:1237–1243. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2014.885061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jandaghi P, Noroozi M, Ardalani H, Alipour M. Lemon balm: A promising herbal therapy for patients with borderline hyperlipidemia—A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Med. 2016;26:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong GS, Kwon OK, Park BY, Oh SR, Ahn KS, Chang MJ, Oh WK, Kim JC, Min BS, Kim YC. Lignans and coumarins from the roots of Anthriscus sylvestris and their increase of caspase-3 activity in HL-60 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:1340–1343. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesting JR, Staerk D, Tejesvi MV, Kini KR, Prakash HS, Jaroszewski JW. HPLC‐SPE‐NMR Identification of a Novel Metabolite Containing the Benzo [c] oxepin Skeleton from the Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis virgatula Culture. Planta Med. 2009;75:1104–1106. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaled M, Jiang ZZ, Zhang LY. Deoxypodophyllotoxin: A promising therapeutic agent from herbal medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;149:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby P, Dunne A, King DH, Corey L. Double-blind randomized clinical trial of self-administered podofilox solution versus vehicle in the treatment of genital warts. Am J Med. 1990;88:465–469. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90424-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komericki P, Akkilic-Materna M, Strimitzer T, Aberer W. Efficacy and safety of imiquimod versus podophyllotoxin in the treatment of anogenital warts. Sex Trans Dis. 2011;38:216–218. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f68ebb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konuklugil B. Aryltetralin lignans from genus Linum. Fitoterapia. 1996a;67:379–381. [Google Scholar]

- Konuklugil B. Investigation of podophyllotoxin in some plants in Lamiaceae using HPLC. J Fac Pharm Ankara. 1996b;25:23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Koulman A, Kubbinga ME, Batterman S, Woerdenbag HJ, Pras N, Woolley JG, Quax WJ. A phytochemical study of lignans in whole plants and cell suspension cultures of Anthriscus sylvestris. Planta Med. 2003;69:733–738. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kour A, Shawl AS, Rehman S, Sultan P, Qazi PH, Suden P, Khajuria RK, Verma V. Isolation and identification of an endophytic strain of Fusarium oxysporum producing podophyllotoxin from Juniperus recurva. World J Microb Biot. 2008;24:1115–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnt M, Rimpler H, Heinrich M. Lignans and other compounds from the Mixe Indian medicinal plant Hyptis verticillata. Phytochemistry. 1994;36:485–489. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Patil D, Rajamohanan PR, Ahmad A. Isolation, purification and characterization of vinblastine and vincristine from endophytic fungus Fusarium oxysporum isolated from Catharanthus roseus. Plos One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Pal T, Sharma N, Kumar V, Sood H, Chauhan RS. Expression analysis of biosynthetic pathway genes vis-à-vis podophyllotoxin content in Podophyllum hexandrum Royle. Protoplasma. 2015;252:1253–1262. doi: 10.1007/s00709-015-0757-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupchan SM, Hemingway JC, Knox JR. Tumor inhibitors VII Podophyllotoxin the active principle of Juniperus virginiana. J Pharm Sci. 1965;54:659–660. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600540443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusari S, Lamshöft M, Spiteller M. Aspergillus fumigatus Fresenius, an endophytic fungus from Juniperus communis L Horstmann as a novel source of the anticancer pro‐drug deoxypodophyllotoxin. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107:1019–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusari S, Zühlke S, Spiteller M. Chemometric Evaluation of the Anti‐cancer Pro‐drug Podophyllotoxin and Potential Therapeutic Analogues in Juniperus and Podophyllum Species. Phytochem Analysis. 2011;22:128–143. doi: 10.1002/pca.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey C, Goodall R, Tennvall GR, Maw R, Kinghorn G, Fisk P, Barton S, Byren I. Randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of podophyllotoxin solution, podophyllotoxin cream, and podophyllin in the treatment of genital warts. Sex Trans Infect. 2003;79:270–275. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.4.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z, Zhang J, Zhang X, Li J, Zhang X, Zhao C. Endophytic fungus from Sinopodophyllum emodi (Wall) Ying that produces Podophyllotoxin. J Chromatogr Sci. 2015;124 doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmv124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Grassi J, Akhmedjanova V, Debiton E, Balansard G, Beliveau R, Barthomeuf C. Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated drug efflux by eudesmin from Haplophyllum perforatum and cytotoxicity pattern versus diphyllin, podophyllotoxin and etoposide. Planta Med. 2007;73:1563. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JF, Sang CY, Xu XH, Zhang LL, Yang X, Hui L, Zhang JB, Chen SW. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity on human cancer cells of carbamate derivatives of 4β-(1, 2, 3-triazol-1-yl) podophyllotoxin. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;64:621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YQ, Tian J, Qian K, Zhao XB, Morris‐Natschke SL, Yang L, Nan X, Tian X, Lee KH. Recent Progress on C‐4‐Modified Podophyllotoxin Analogs as Potent Antitumor Agents. Med Res Rev. 2015;35:1–62. doi: 10.1002/med.21319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loike JD. VP16-213 and podophyllotoxin. Cancer Chemoth Pharm. 1982;7:103–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00254530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Hu Y, Kong W, Yang M. Evaluation and structure-activity relationship analysis of a new series of arylnaphthalene lignans as potential anti-tumor agents. Plos one. 2014;9:e93516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata M, Itoh K, Tachibana S. Extractives of Juniperus chinensis L I: Isolation of podophyllotoxin and yatein from the leaves of J chinensis. J Wood Sci. 1998;44:397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Muranaka T, Miyata M, Ito K, Tachibana S. Production of podophyllotoxin in Juniperus chinensis callus cultures treated with oligosaccharides and a biogenetic precursor in honour of Professor GH Neil Towers 75th Birthday. Phytochemistry. 1998;49:491–496. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem M, Ram M, Alam P, Ahmad MM, Mohammad A, Al-Qurainy F, Khan S, Abdin MZ. Fusarium solani, P1, a new endophytic podophyllotoxin-producing fungus from roots of Podophyllum hexandrum. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2012;6:2493–2499. [Google Scholar]

- Passarella D, Peretto B, Yepes RB, Cappelletti G, Cartelli D, Ronchi C, Snaith J, Fontana G, Danieli B, Borlak J. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel thiocolchicine–podophyllotoxin conjugates. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M, Alfermann WA. The production of cytotoxic lignans by plant cell cultures. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2001;55:135–142. doi: 10.1007/s002530000510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri SC, Nazir A, Chawla R, Arora R, Riyaz-ul-Hasan S, Amna T, Ahmed B, Verma V, Singh S, Sagar R. The endophytic fungus Trametes hirsuta as a novel alternative source of podophyllotoxin and related aryl tetralin lignans. J Biotechnol. 2006;122:494–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos AC, Peláez R, López JL, Caballero E, Medarde M, San Feliciano A. Heterolignanolides Furo-and thieno-analogues of podophyllotoxin and thuriferic acid. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:3963–3977. [Google Scholar]

- Samadi A, Jafari M, Nejhad NM, Hossenian F. Podophyllotoxin and 6-methoxy podophyllotoxin Production in Hairy Root Cultures of Liunm mucronatum ssp mucronatum. Pharmacogn Mag. 2014;10:154. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.131027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Feliciano A, Del Corral JMM, Gordaliza M, Castro MA. Acetylated lignans from Juniperus sabina. Phytochemistry. 1989a;28:659–660. [Google Scholar]

- San Feliciano A, Medarde M, Lopez JL, Puebla P, Del Corral JMM, Barrer AF. Lignans from Juniperus thurifera. Phytochemistry. 1989b;28:2863–2866. [Google Scholar]

- Sasheva P, Ionkova I. Podophyllotoxin production by cell culturrs of Linum thracicum ssp thracicum degen elicited eith methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid. Cr Acad Bul Sci. 2015:883–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz B, Boyle C, Draeger S, Römmert AK, Krohn K. Endophytic fungi: a source of novel biologically active secondary metabolites. Mycol Res. 2002;106:996–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel V, Windhövel J, Eaton G, Alfermann WA, Arroo RR, Medarde M, Petersen M, Woolley JG. Biosynthesis of podophyllotoxin in Linum album cell cultures. Planta. 2002;215:1031–1039. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0834-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SY, Yong Y, Kim CG, Lee YH, Lim Y. Deoxypodophyllotoxin induces G 2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in HeLa cells. Cancer Lett. 2010;287:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltani J, Moghaddam M S H. Fungal Endophyte Diversity and Bioactivity in the Mediterranean Cypress Cupressus sempervirens. Curr Microbiol. 2015;70:580–586. doi: 10.1007/s00284-014-0753-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Sakakibara N, Umezawa T, Shimada M. Survey and enzymatic formation of lignans of Anthriscus sylvestris. J Wood Sci. 2002;48:536–541. [Google Scholar]

- Syed T, Lundin S, Ahmad M. Topical 03% and 05% podophyllotoxin cream for self-treatment of molluscum contagiosum in males. Dermatology. 1994;189:65–68. doi: 10.1159/000246787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsugi T, Shibata J, Sugimoto Y, Aoyagi K, Wierzba K, Kobunai T, Terada T, Oh-hara T, Tsuruo T, Yamada Y. Antitumor activity of a novel podophyllotoxin derivative (TOP-53) against lung cancer and lung metastatic cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2809–2814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Krogh G, Hellberg D. Self-treatment using a 05% podophyllotoxin cream of external genital condylomata acuminata in women A placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Sex Trans Dis. 1991;19:170–174. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199205000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Krogh G, Szpak E, Andersson M, Bergelin I. Self-treatment using 025%-050% podophyllotoxin-ethanol solutions against penile condylomata acuminata: a placebo-controlled comparative study. Genitourin Med. 1994;70:105–109. doi: 10.1136/sti.70.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Li G, Lu H, Zheng Z, Huang Y, Su W. Taxol from Tubercularia sp strain TF5, an endophytic fungus of Taxus mairei. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;193:249–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner J, Jirovetz L, Schmidt E. Callitris intratropica RT Baker & HG Smith as a Novel Rich Source of Deoxypodophyllotoxin. Curr Bioact Compd. 2015;11:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. Treatment of genital warts—what's the evidence? Int J Std Aids. 2002;13:216–222. doi: 10.1258/0956462021924992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wink M. Medicinal plants: a source of anti-parasitic secondary metabolites. Molecules. 2012;17:12771–12791. doi: 10.3390/molecules171112771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrasidlo W, Gaedicke G, Guy RK, Renaud J, Pitsinos E, Nicolaou KC, Reisfeld RA, Lode HN. A novel 2 ‘-(N-methylpyridinium acetate) prodrug of paclitaxel induces superior antitumor responses in preclinical cancer models. Bioconjugate Chem. 2002;13:1093–1099. doi: 10.1021/bc0200226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Lv M, Tian X. A review on hemisynthesis, biosynthesis, biological activities, mode of action, and structure-activity relationship of podophyllotoxins: 2003-2007. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:327–349. doi: 10.2174/092986709787002682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefzadi M, Sharifi M, Chashmi NA, Behmanesh M, Ghasempour A. Optimization of podophyllotoxin extraction method from Linum album cell cultures. Pharma Biol. 2010;48:1421–1425. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2010.489564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu PZ, Wang LP, Chen ZN. A new podophyllotoxin-type lignan from Dysosma versipellis var tomentosa. J Nat Prod. 1991;54:1422–1424. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Chen J, Liang Z, Zhao C. New lignans and their biological activities. Chem Biodivers. 2014;11:1–54. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201100433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]