Abstract

Objective

Providing care to one’s child during and after a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is a universally stressful experience, but few psychological interventions have been developed to reduce caregiver distress. The goal of this study was to test the efficacy of a brief cognitive–behavioral intervention delivered to primary caregivers.

Method

Two hundred eighteen caregivers were assigned either best-practice psychosocial care (BPC) or a parent social-cognitive intervention program (P-SCIP). The 5 session P-SCIP was delivered during the HSCT hospitalization. Caregivers completed measures of distress, optimism, coping, and fear appraisals preintervention, 1, 6 months, and 1 year.

Results

P-SCIP reduced caregiver’s distress significantly more than BPC between the pretransplant assessment (Time 1) and 1-month follow-up assessment (Time 2). P-SCIP had a stronger effect than BPC among caregivers who began the hospitalization reporting higher depression and anxiety, and among caregivers whose children developed graft-versus-host disease (GvHD). Long-term treatment effects of P-SCIP were seen in traumatic distress among caregivers who reported higher anxiety pretransplant as well as among caregivers whose children had GvHD at HSCT discharge.

Conclusions

Screening caregivers for elevations in pretransplant anxiety and targeting interventions specifically to these caregivers, as well as targeting caregivers to children who develop GvHD, may prove beneficial.

Keywords: behavioral intervention, pediatric transplantation, parents, caregivers

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is a physically demanding treatment procedure that involves a preparatory regimen of intensive chemotherapy and possibly irradiation followed by an infusion of marrow or peripheral stem cells from a donor (allogeneic transplantation) or from the patient (autologous transplantation). HSCT is considered to be a first-line therapy for many life-threatening hematologic and oncologic diseases. Advances in supportive care such as treatment of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) have improved survival rates, and improvements in donor marrow preparation options have resulted in an increased donor pool and wider variety of diseases for which HSCT is applicable. Both advances have resulted in a dramatic increase in the utilization of HSCT in the treatment of pediatric malignancies and congenital and acquired disorders in the last decade.

Although potentially curative, HSCT is still associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Short-term medical complications include severe mucositis, hepatic toxicities, septicemia, and acute GvHD, and/or an unsuccessful engraftment (Eduardo et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2015). Long-term medical complications can include infections (Ferry et al., 2007), pulmonary disease (Srinivasan et al., 2014), chronic GvHD (Alousi, Bolaños-Meade, & Lee, 2013), endocrine disease (Ferry et al., 2007), neurological problems (Kang et al., in press), as well as second malignancies and disease recurrence (Arico et al., 2010). Despite improved survival statistics, pediatric HSCT remains a risky procedure. Depending on the type of transplant and disease, transplant-related mortality ranges between 20% and 55% in the 5 years following HSCT (Mehta et al., in press; Naik, Premsagar, & Mallikarjuna, 2015).

Caregiver Distress and Psychological Interventions Targeting Distress

The significant medical risks along with the difficult experience of witnessing one’s child undergoing an aversive medical procedure such as HSCT can result in both acute and persistent psychological distress reactions among parents. The available literature suggests that the time immediately preceding and following the transplant can be particularly upsetting for parents, with studies suggesting that between 20% and 66% of caregivers report elevated depression and/or anxiety before the HSCT transfusion (Barrera, Atenafu, Doyle, Berlin-Romalis, & Hancock, 2012; Barrera, Boyd Pringle, Sumbler, & Saunders, 2000; Manne et al., 2001; Rodrigue et al., 1997) and about half report elevations in depression and/or anxiety at HSCT discharge (Streisand, Rodrigue, Houck, Graham-Pole, & Berlant, 2000). Although distress steadily declines for the majority of caregivers after the HSCT (Barrera et al., 2012; Phipps, Dunavant, Lensing, & Rai, 2004), elevated levels of distress persists in a subset of caregivers (Manne et al., 2004; Vrijmoet-Wiersma et al., 2010). Persistent distress has been associated with elevated distress at the time of HSCT (Manne et al., 2004), premorbid child-behavior problems (Phipps et al., 2004), parent coping (Manne et al., 2003), and complications such as infection and organ toxicity (Heinze et al., 2015; Terrin et al., 2013).

Given that caregivers to children undergoing HSCT can experience elevated levels of distress, behavioral interventions that can reduce this distress are needed. To date, most of the psychological interventions developed have focused on caregivers of children with cancer (Mullins et al., 2012; Sahler et al., 2013). There has been one randomized clinical trial (Lindwall et al., 2014), which evaluated the efficacy of a child and parent massage and humor therapy intervention. Parents were randomly assigned to receive a child-targeted massage and humor therapy intervention; the child intervention, a parent-targeted massage, and humor therapy intervention; or standard care. Parental distress and well-being were assessed weekly through Week 3 post-HSCT. Results indicated that there were no differences between study arms on distress or well-being over the 7-week period because caregivers in both study arms had reductions in distress. It is possible that the massage and humor intervention was not sufficiently intensive and/or did not address the key coping skills that might facilitate coping with the unique stressors that parents encounter during the HSCT experience.

Cognitive-Social Processing Theory and P-SCIP

We used cognitive-social processing theory of adjustment to traumatic events (Creamer, Burgess, & Pattison, 1992; Tait & Silver, 1989) to guide our work. This theory proposes that traumatic life experiences cause people to question core beliefs they hold about themselves, their relationships, and their world (Janoff-Bulman, 1992). Confronting, contemplating, and reevaluating the traumatic event and its meaning may reduce distress by helping people integrate the traumatic event’s meaning into the person’s mental model (Lepore, 2001; McCann & Pearlman, 1990). This process is called cognitive processing and occurs when people reappraise the event to fit their preexisting views and/or when people change their beliefs about themselves, their relationships, and their world. Among caregivers to children undergoing HSCT, cognitive processing may entail interpreting the HSCT in personally meaningful terms (e.g., “My child and I have grown stronger”) or integrating the threatening or confusing aspects of the HSCT into a coherent conceptual framework (e.g., “Things like this happen to children and they can adjust”). Talking with supportive family or friends, which has been labeled social processing (Lepore, 2001) facilitates cognitive processing (Albrecht, Burleson, & Goldsmith, 1994; Pennebaker & Harber, 1993; Rimé, 1995). Research among caregivers to children undergoing HSCT has supported the role of cognitive and social processes. Reframing the HSCT in more positive terms by using acceptance, positive reappraisal, and humor are associated with decreases in depressive symptoms over the course of the 6-month period post-HSCT (Manne et al., 2003), and sharing feelings with supportive family and friends is also associated with less long-term distress (Manne et al., 2003; Nelson, Miles, & Belyea, 1997).

For the proposed study, we used this information to develop a Parent Social-Cognitive Processing Intervention Program (P-SCIP). P-SCIP is an individual intervention that targets cognitive and social processing strategies that prior research has suggested are associated with caregiver adjustment. These skills include the ability to accurately appraise changeable and unchangeable components of HSCT-related stressors and matching coping responses to each component (problem-solving vs. focusing on managing emotions). Caregivers are taught to use positive reappraisal; evaluate their values, priorities, and goals; accept what cannot be changed; and improve their social processing (expressing feelings and needs to family and friends). P-SCIP included an interactive CD-ROM, which was used to enhance session content and facilitate practice of effective coping.

Study Aims

The study had three aims. The first aim was to compare P-SCIP with best-practice psychosocial care (BPC). BPC was designed to provide a comparison for the P-SCIP intervention. Caregivers were provided materials about emotional responses that caregivers and children have to HSCT, managing one’s child during the hospitalization, the provision of respite care, and the provision of a way to communicate with the child when not in the room. Although BPC was not equated to P-SCIP with regard to time and attention provided by the therapist, BPC offered widely available information and assistance for caregivers. We hypothesized that P-SCIP would result in a greater reduction in our primary outcomes of depression, anxiety, and traumatic distress responses, and a greater improvement in our secondary outcome, positive well-being, as compared with BPC. Traumatic distress was included as a primary outcome due to the prevalence of traumatic stress responses in this population (see Packman et al., 2010, for a review of this topic). Positive well-being was evaluated as a secondary outcome because positive outcomes are an important component of the caregiving experience and behavioral interventions for parent caregivers have assessed positive well-being as an indicator of treatment response (Lindwall et al., 2014) Because P-SCIP targeted coping skills that to be used to manage stressors experienced during the year after HSCT, we proposed that the beneficial effects of P-SCIP would have a persistent effect over the one year post-HSCT that caregivers were evaluated.

The second and exploratory aim was to evaluate possible psychosocial and medical treatment moderators. From a clinical perspective, identifying the characteristics of individuals who benefit more from therapies can help clinicians decide which individuals should be offered particular therapies. The selection of putative moderators was based on prior research. We selected three moderators representing three types of variables. First, because greater pretherapy distress is a known moderator of better therapy outcomes (Chilcot, Norton, & Hunter, 2014; Hopko, Clark, Cannity, & Bell, 2016), we predicted that P-SCIP would be more efficacious than BPC among more distressed caregivers. Second, because less optimistic individuals are more responsive to interventions that bolster positive outlooks (Sergeant & Mongrain, 2011, 2014), and P-SCIP targeted cognitive restructuring and benefit finding, we proposed that P-SCIP would be more effective for caregivers reporting less preintervention optimism. Third, prior work has suggested that individuals facing a more difficult disease challenge (e.g., greater impairment) benefit more from therapy than those who do not (Manne et al., 2007) we proposed that P-SCIP would be more effective for caregivers whose children had an HSCT that was less likely to have a successful outcome.

The third aim was to examine possible P-SCIP mechanisms. We predicted that, compared with BPC, caregivers assigned to the P-SCIP intervention would exhibit a greater increase in adaptive ways of processes that P-SCIP targeted (e.g., humor, positive reappraisal, acceptance, seeking support, problem solving), and these changes would mediate the changes in distress and well-being over time.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from four HSCT centers across the United States. Eligible participants were primary caregivers (biological or foster parents) of children under 19 years of age who were scheduled for HSCT within the next month. Additional eligibility criteria were as follows: (a) child could not have a diagnosis of medulloblastoma or other cancer of the brain; (b) caregiver must have residential phone service; and (c) caregiver had to speak, read, and write in English or Spanish (two of the four HSCT centers were equipped to enroll Spanish-speakers). Only one primary caregiver per family could participate. When both parents provided primary care, they decided which one would participate.

Procedure

Eligible caregivers were identified by the research assistant at the study site during weekly HSCT meetings with the medical team and were approached in the outpatient clinic in the week before the child’s scheduled transplant. The study was described in detail during this visit, and interested caregivers reviewed and signed the site-specific institutional review board–approved consent and Time 1 survey. Participants were randomly assigned to BPC or P-SCIP by a computerized program from the Biostatistics Program at FCCC (PRESAGE). Randomization was done after the consent and the Time 1 survey were completed. Randomization was stratified by caretaker gender (male or female) and language (English or Spanish) to ensure equal distribution of demographics across study groups. The research staff recruiting and administering surveys, interventionists, and participants were not blinded to study conditions. Caregivers completed four assessments: one at baseline (preintervention) and three follow-ups at 1, 6, and 12 months postbaseline. Time 1 survey was completed in person, Time 2 was completed either in person (106 of the 195 participants completing Time 2 had children who were still hospitalized at Time 2) or by phone or mail (89 of the 195 participants completing Time 2 had a child who was at home). Times 3 and 4 were completed by phone or mail. For participants who were at home, surveys were mailed to the participants. Caregivers were paid $25 each for the first two assessments and $50 each for the third and fourth assessments. Recruitment began in October 2008 and ended in December 2013.

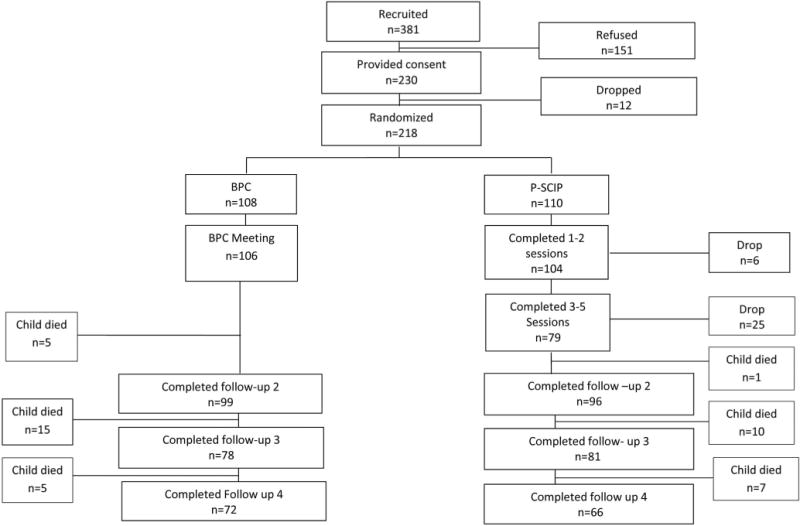

The study CONSORT is shown in Figure 1. Of the 381 caregivers who were approached for study participation, 218 consented and completed the Time 1 survey (57.2%), 151 caregivers refused participation (39.6%), and 12 caregivers consented but dropped out after consenting and did not complete the Time 1 survey (3.1%). The most common reasons participants refused were “study would take too much time” (23%), “too overwhelmed/ stressed” (20%), and “not interested” (23%). Of the 13 caregivers who dropped after consenting, the reasons were caregiver was too tired (n = 5), the caregiver did not have time (n = 1), the HSCT occurred before the Time 1 survey was completed (n = 3), the HSCT was canceled (n = 1), the survey was upsetting (n = 2), and the caregiver was not proficient in English (n = 1). Comparisons between the study participants and refusers with available data indicated that there were no significant differences with regard to caregiver age, income, education, ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, other), marital status (married/not married), child age, diagnosis (cancer or noncancer), time since child’s diagnosis, child gender, child age at diagnosis, child ethnicity, and study site. The acceptance rate was significantly lower at one site (MSKCC; 50%) versus the other sites (62%–68%; chi-square = 8.5 p < .05). Non-Hispanic Black caregivers were more likely to participate (71.1%) than refuse (28.9%), and Hispanic participants were also more likely to participate (71.4%) than refuse (28.6%).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants in the study. BPC = best-practice psychosocial care; P-SCIP = parent social-cognitive intervention program.

Of the 218 participants, 195 completed the 1-month follow-up assessment, 159 completed the 6-month follow-up assessment, and 138 completed the 1-year follow-up assessment. Caregivers were dropped from the study if their child passed away during participation. By the 1-year follow-up assessment, 20.6% of participants’ children had passed away (n = 45). Thus, completion rates were calculated based on caregivers of children who were still alive at that time point. Excluding drop out due to the child’s death, completion rates in BPC were 98% at the 1-month follow-up, 88.4% at the 6-month follow-up, and 88.9% at the 1-year followup. Completion rates in P-SCIP were 88.1% at the 1-month followup, 82% at the 6-month follow-up, and 71.7% at the 1-year follow-up. The return rate in the P-SCIP arm was lower, particularly at the 1-month and 1-year follow-ups.

Participants who completed all four surveys were compared with participants who dropped (for reasons other than the child’s death) after completing the initial, 1-month, 6-month, or 1-year follow-ups. Comparisons for the initial demographic, child medical (HSCT type, time since diagnosis, cancer vs. non-cancer diagnosis), and psychological (all outcomes and mediators) variables did not indicate any differences.

Intervention Conditions

P-SCIP

This individually delivered intervention consisted of five 60-min sessions over a span of 2 to 3 weeks after HSCT and an interactive CD-ROM. During Session 1, (“Introduction, Stress, and Worries About Your Child”), caregivers were oriented to the intervention, the caregiver’s HSCT experience was reviewed, major stressors were identified, and caregivers learned deep-breathing relaxation. Session 2 (“Coping With Solvable Concerns about HSCT”) covered types of coping, how to appraise changeable and unchangeable components of stressors, when to use problem-focused coping, common child-behavior problems during HSCT (e.g., separation anxiety) and how to manage them, and a focused breathing relaxation practice. During Session 3 (“Coping With Unchangeable Problems With HSCT”), four ways to manage unchangeable problems were reviewed: Change how you think about a situation; change your values, priorities, or goals; distract yourself; and learn to accept the situation. Caregivers discussed ways to manage expectations, accept what has changed, identify any benefits in the experience (e.g., “I learned how strong my child is”), and practiced cognitive restructuring skills by choosing a situation that caused distress where they could not change the outcome (e.g., worrying about the HSCT outcome). They also practiced progressive muscle relaxation. Session 4 (“Social Life”) focused on communication and the importance of expressing feelings and needs, as well as guided imagery relaxation. Caregivers identified a situation where they could ask for more assistance and one where they could share feelings with and role played strategies to do these tasks. During Session 5 “Putting your skills to work,” skills and progress were reviewed, caregivers used a post-HSCT issue to practice the skills learned, and caregivers worked on managing postdischarge issues. They were provided a workbook of 65 handouts during sessions, postsession homework assignments were given, and caregivers were asked to review CD-ROM modules corresponding to the material. Participants were assigned a total of 220 min of the P-SCIP CD-ROM. Spanish language versions of P-SCIP materials were available. Materials for the intervention were translated into Spanish and then back-translated into English by two members of the research team, and then reviewed by a bilingual study interventionist for accuracy. The CD-ROM was translated by a translation service that back-translated them after initial translation.

BPC

BPC had four components: (a) a DVD developed by the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) titled, “Discovery to Recovery: A Child’s Guide to Bone Marrow Transplant,” which is a 62-min video that covers medical information about the HSCT procedure, common emotional reactions children have during the HSCT, advice from parents about how to handle the hospitalization, and parent/sibling testimonials about their psychological reactions during the HSCT; (b) a pamphlet covering common caregiver issues during HSCT created by the National Bone Marrow Transplant Link titled, “Top Tips for Parent Caregivers during the BMT Process” which was eight pages in length; (c) the offer of 5 hr of respite care (e.g., watching the child while the caregiver left the room); and (d) the provision of a walkie-talkie to communicate with the child while not in the room. Spanish language versions of all BPC materials were available. These materials (as well as all measures not already available in Spanish) were translated by a professional translation service.

Intervention Training, Supervision, and Fidelity

Graduate-level therapists (postdoctoral fellows, clinical psychology students) provided P-SCIP. Therapists were trained by the first author, who reviewed the manual, handouts, engaged in role play, and discussed difficult situations. Supervision was provided by the first author or the postdoctoral fellow (SM) after every session and before the subsequent session. The supervisor listened to the tape and completed the fidelity coding sheet (which was the same scoring as the fidelity coding). During supervision, she discussed ways to tailor material to meet caregiver needs. BPC was delivered by staff members at each site who were trained by the project manager in the elements of BPC. Fidelity feedback was provided on a regular basis.

Outcome Measures (All Time Points)

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). Cronbach’s alphas were .86, .87, .93, and .91 for the Time 1 through the Time 4 time points.

Anxiety

Anxiety was assessed using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988). Cronbach’s alphas were .90, .91, .91, and .93 for the Time 1 to the Time 4 assessments.

Traumatic distress

Traumatic distress was measured using the Impact of Event Scale (IES; Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979). The IES contains 22 items and uses a 4-point Likert scale. The instructions asked the participant to rate responses related to the child’s transplant. Cronbach’s alphas were .92, .93, .94, and .94, for the Time 1 to the Time 4 assessments.

Positive well-being

The 14-item positive well-being scale from the Mental Health Inventory was used (Veit & Ware, 1983). Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s alphas were .89, .91, .92, and .93, for the Time 1 through the Time 4 time points.

Covariates

Caregiver sociodemographic variables

Caregiver ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and other), relationship status (mother/not mother), marital status (married/not married), education level (high school, GED or less/more than high school degree), and age were included as covariates.

Child demographic and medical variables

Child sex, time since diagnosis, and whether or not the child died over the course of the study were included as covariates.

Mediators (Times 1, 2, and 4 only) and Psychosocial Moderator

Coping

Five subscales of the brief COPE scale were used to assess acceptance (e.g., “I’ve been getting used to the idea that this has happened”), humor (e.g., “I’ve been making jokes about it”), positive reappraisal (e.g., “I’ve been trying to learn something from the experience”), seeking emotional support (e.g., “I’ve been getting comfort and understanding from someone”), and problem solving (e.g., I’ve been thinking hard about what steps to take”; Carver, 1997). Two items assessed each strategy, and items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale. Caregivers were asked to rate the ways they were coping with the child’s HSCT. Cronbach’s alphas were acceptance, α = .80, .85, .87; humor, α = .71, .80, .80; positive reappraisal, α = .72, .72, .88; seeking emotional support, .74, .73, and .78; and problem solving, α = .64, .76, .73, at the Time 1, 2, and 4 assessments, respectively.

Fear appraisals

The construct had four components (DuHamel et al., 2004): (a) Three items assessed caregivers’ perception of their own potential for future suffering (e.g., “How scared are you that you’ll never be able to put the transplant experience behind you?”) rated on a scale from 0 to 8; (b) caregivers listed the number of fears for the child’s future in six life domains (e.g., social life). The number of fears listed by mothers was totaled to form a sum measure of total number of fears; (c) the above fears were rated in terms of the frequency of the caregiver’s worry regarding the child’s future (“How frequently do you have this worry?”) in the same six domains on a scale from 1 to 7, and; (d) the intensity of the caregivers worry for each fear (“When you have this fear how intense is it?”) was rated on a scale from 1 to 100.

Optimism

The Life Orientation Test (LOT; Scheier & Carver, 1985) was used to assess optimism at Time 1. This 13-item scale had good reliability in the current study (α = .80).

Intervention Evaluation Measures

Treatment expectancy

A five-item Expectancy Rating Form (Borkovec & Nau, 1972) was administered to P-SCIP participants at the end of Session 1 (e.g., “How successful do you think these sessions will be for you?”). Cronbach’s alpha was .89.

Therapeutic alliance

The Working Alliance Inventory (WAI; Horvath & Greenberg, 1989) is a 36-item self-report questionnaire with three subscales: goals, tasks, and bond. The WAI was administered after the second and fifth sessions. A sample item is “I am clear on what my responsibilities are in these sessions.” Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .77 to .87.

Treatment evaluations

P-SCIP participants completed a 15-item evaluation of the in-person sessions and handbook after Session 5 and an 11-item evaluation of the CD-ROM. Participants rated how helpful each session was, whether they would recommend the sessions to another caregiver, how interesting and important the sessions were, whether they learned something new, and how much of the homework they completed. Items were rated on a seven-point Likert scale. Similar items were used for the CD-ROM evaluation. Therapists also reported whether participants completed each home assignment. BPC participants completed a 16-item evaluation of the Discovery to Recovery DVD and the “Tips for Caregivers” pamphlet. Participants reported whether they viewed the DVD and completed the same ratings as used for P-SCIP. They reported if they read the tips pamphlet as well as its helpfulness. Scale means were calculated.

Treatment Fidelity

P-SCIP fidelity criteria consisted of topics covered in each session, whether in-session exercises were conducted, and whether home assignments were given. The BPC fidelity checklist consisted of the four activities in the meeting (see above).

Analytic Approach

Multilevel modeling (MLM) was used to examine whether there were significant differences between the P-SCIP versus BPC groups over time. In our primary analysis both time and treatment were treated as categorical. This approach yields a main effect for treatment, a main effect for time, and an interaction between time and treatment. Caregiver covariates included in the analyses were three effects-coded variables representing ethnicity, relationship (mother/not mother), marital status (married/not married), education (posthigh school/high school or less), age, and initial traumatic distress. Child covariates included sex, time since diagnosis, whether the child was on the inpatient unit when Time 2 was completed, and whether the child died. The MLM approach has the advantage that it does not delete participants with missing data at some time points, as would be the case if a traditional analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used. Thus, this analysis utilizes all available data.

Moderation analyses also used MLM. To test for moderation by participant ethnicity/race, we included a four-level race variable into our analysis, treating time and condition as categorical variables. No interactions between race and condition emerged. For moderation analyses with continuous or dichotomous moderators, we adopted a slightly different approach. Specifically, we simplified the analysis by using MLM with a regression approach in which condition was effects coded (BPC = 1, P-SCIP = −1) and time was treated as a quantitative variable that was coded in months (0, 1, 6, 12) and then grand-mean centered. Moderator variables were grand-mean centered (e.g., optimism, depression, anxiety, traumatic distress, and well-being all at baseline) or effects coded (e.g., malignancy, GvHD status, donor relation—coded as 1 self or sibling, −1 = other donor). Moderation analyses included the same set of caregiver and child covariates used in the primary analyses. Note that because the focus was specifically on whether the moderating variables moderated the effects of the treatment, we discuss only results for interactions involving both the moderator and the treatment. More detailed information is available from the authors.

Results

Preintervention Differences and Distress Characteristics

Table 1 contains summary data for the participants by study condition regarding demographic and medical characteristics. The sample was ethnically and socioeconomically diverse (more than half of the sample was not White; a quarter had a high school or lower level of education). Multivariate analysis of covariance and chi-square tests revealed no differences between the two conditions regarding demographic or medical variables. Overall, an examination of hospital site as a covariate did not reveal that this variable was a significant covariate. Thus, data from hospital sites were combined in all analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample

| Characteristics | Full sample (n = 218)

|

BPC (n = 108)

|

P-SCIP (n = 110)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | |

| Caregiver age (years) | 37.4 (8.1) | 37.8 (8.5) | 37.1 (7.6) | |||

| Caregiver role | ||||||

| Mother | 192 (88.0) | 96 (88.9) | 96 (87.3) | |||

| Father | 18 (8.3) | 7 (6.5) | 11 (10.0) | |||

| Other | 8 (3.7) | 5 (3.7) | 2 (1.8) | |||

| Caregiver ethnicity | ||||||

| non-Hispanic White | 102 (46.8) | 50 (45.5) | 52 (48.1) | |||

| non-Hispanic Black | 54 (24.8) | 31 (28.2) | 23 (21.3) | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 45 (20.6) | 24 (21.8) | 21 (19.4) | |||

| Other | 17 (7.8) | 5 (4.5) | 12 (11.1) | |||

| Caregiver marital status | ||||||

| Married | 151 (69.3) | 74 (68.5) | 77 (70) | |||

| Single, divorced, widowed | 67.1 (30.7) | 34 (31.5 | 33 (30.0) | |||

| Caregiver education | ||||||

| High school or less | 55 (25.2) | 26 (24.1) | 29 (26.4) | |||

| Some college | 80 (36.7) | 37 (34.3) | 43 (39.0) | |||

| College degree | 37 (17.0) | 21 (19.4) | 16 (14.5) | |||

| Higher than college | 46 (21.1) | 24 (22.2) | 22 (20.0) | |||

| Caregiver income | $50,000–$59,999 | $50,000–$59,999 | $50,000–$59,999 | |||

| Site | ||||||

| Emory | 86 (39.4) | 42 (38.9) | 44 (40.0) | |||

| MSKCC | 65 (29.85) | 33 (30.6) | 32 (29.1) | |||

| CHLA | 8 (3.7) | 6 (5.6) | 2 (1.8) | |||

| Columbia | 59 (27.1) | 27 (25.0) | 32 (29.1) | |||

| Child age | 8.5 (5.3) | 8.1 (5.3) | 8.9 (5.3) | |||

| Child gender | ||||||

| Male | 123 (56.4) | 61 (56.5) | 62 (56.4) | |||

| Female | 95 (43.6) | 47 (43.5) | 48 (43.6) | |||

| Types of HSCT | ||||||

| Autologous | 39 (17.9) | 21 (31.5) | 18 (16.4) | |||

| Allogeneic-sibling | 71 (32.8) | 53 (49.1) | 37 (33.6) | |||

| Allogeneic-other donor | 108 (49.5) | 34 (31.5) | 55 (500) | |||

| Diagnostic group | ||||||

| All | 56 (25.7) | 22 (20.4) | 34 (30.9) | |||

| AML | 43 (19.7) | 26 (24.1) | 17 (15.5) | |||

| Other leukemia | 2 (.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.8) | |||

| HD/NHL | 15 (6.9) | 5 (4.6) | 10 (9.1) | |||

| Solid tumor | 30 (13.8) | 17 (15.7) | 13 (11.8) | |||

| Non-malignancy | 72 (33.0) | 38 (35.2) | 34 (30.9) | |||

Note. BCP = best-practice psychosocial care; P-SCIP = parent social-cognitive intervention program; ALL = acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML = acute myelogenous leukemia; HD = Hodgkin disease; NHL = non-Hodgkin lymphoma; MSKCC = Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; CHLA = Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles.

Treatment Attendance and Fidelity

72% of P-SCIP participants attended three to five sessions, and 81% of P-SCIP participants attended one or two sessions. Six caregivers (5.5%) did not attend any P-SCIP sessions. Common reasons for dropout included feeling overwhelmed, too busy, or the child’s health worsening. Most caregivers who dropped out did not provide a reason. Treatment attendance for BPC meetings was 98%. Two caregivers did not attend because the child died.

Of the 416 P-SCIP sessions, 94% percent were audiotaped, audible, and rated for fidelity. Fidelity across sessions was 93%. Individual session fidelity was as follows: Session 1 = 93.4%, Session 2 = 93.8%, Session 3 = 93%, Session 4 = 88.6%, and Session 5 = 93% (range 52.5%–100%). The average fidelity for BPC was 98% (range = 60%–100%).

Treatment Expectancy, Working Alliance, Treatment Evaluation, and Intervention Use

Average treatment expectancy scores across P-SCIP participants were high (Item M = 3.1, SD = 0.61, on a 4-point Likert scale). Working alliance-bond, task, and goal subscale scores after Session 2 (M = 71.2, 73.4, and 72.6) and Session 5 (M = 73.4, 73.1, and 74.8) were similar or slightly higher than alliance scores reported for other studies evaluating cognitive–behavioral treatments for cancer patients (M = 71.1, 69.4, 68.0, for bond, task, and goal, respectively), suggesting satisfactory working alliance. In terms of treatment evaluation, the P-SCIP CD-ROM was evaluated highly (item M = 5.8, SD = 1.0; 7 was highest rating possible). 86% of participants reported using it. The P-SCIP intervention was rated relatively well (item M = 3.6, SD = 1.5; 5 = strongly agree). Average time spent in the CD-ROM among P-SCIP participants as calculated from the computer program attached to the CD among those who completed the corresponding P-SCIP session was 96.3 min (SD = 94.9 min; Mdn = 54 min), and between 0 and 1 min (no use) was reported for 25% of participants. The average viewing time for each module ranged from 3 min (Module 6) to 10.5 min (contained video clips).

The BPC was also evaluated highly (item M = 5.3, SD = 1.1; 7 = strongly agree). Ninety-four percent of participants reported using the Discovery to Recovery DVD, and 75% of participants reported reading the tips pamphlet. Fifty-nine percent of BPC participants used respite care.

Intervention Effects on Global and Traumatic Distress and Well-being

In terms of covariates, caregiver marital status was a significant predictor of each of the four outcomes, such that married caregivers were significantly less depressed, anxious, distressed, and had higher well-being. Higher Time 1 traumatic distress was significantly associated with higher depression, anxiety, and traumatic distress, but it was not related to well-being. In addition, Hispanic participants were significantly higher than White participants in positive well-being. The only other significant covariate was the caregivers’ age predicting traumatic distress such that older caregivers reported higher traumatic distress.

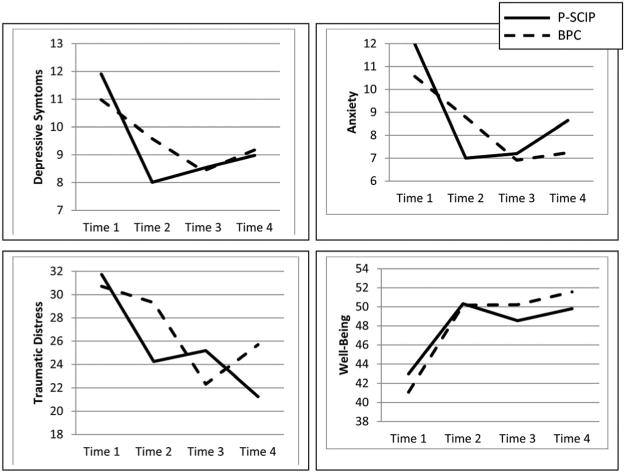

The estimated marginal means (controlling for the covariates) and standard errors for the four primary outcomes, depression, anxiety, traumatic distress, and well-being are presented in Table 2, and the marginal means over time and condition are depicted in Figure 2. As can be seen in the table, there was no evidence of a main effect for the treatment. However, there was evidence of change over time on average for all four outcomes, as well as significant interactions between the treatment and time for anxiety and global distress and a marginally significant interaction for depression. There was no evidence of an interaction for well-being. Across all of the variables, post hoc means tests of the main effect of time showed significant drops in negative outcomes (or a positive increase in well-being) from Time 1 as compared with the other three time points. That is, averaging across treatment groups for each variable, the Time 1 outcome differed significantly from the other time points, but those other time points did not differ from one another.

Table 2.

Estimated Marginal Means and Standard Errors, Along With Statistical Tests Evaluating the Effects of Condition, Time, and the Condition × Time Interaction on Primary Outcomes Controlling for Covariates

| Variable | Time 1 M (SE) |

Time 2 M (SE) |

Time 3 M (SE) |

Time 4 M (SE) |

Condition main effect dfnum = 1 F(dfdenom) |

Time main effect dfnum = 3 F(dfdenom) |

Condition × Time interaction dfnum = 3 F(dfdenom) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms | |||||||

| BPC | 10.98 (0.80) | 9.58 (0.80) | 8.42 (0.87) | 9.18 (0.92) | 0.04 | 9.42** | 2.24† |

| P-SCIP | 11.91 (0.80) | 8.01 (0.80) | 8.52 (0.85) | 8.98 (0.94) | (204) | (473) | (474) |

| Anxiety | |||||||

| BPC | 10.57 (0.92) | 8.78 (0.92) | 6.91 (0.98) | 7.24 (1.03) | 0.10 | 16.41** | 4.08** |

| P-SCIP | 11.99 (0.91) | 7.00 (0.92) | 7.20 (0.96) | 8.64 (1.05) | (187) | (462) | (463) |

| Traumatic distress | |||||||

| BPC | 30.72 (1.87) | 29.31 (1.88) | 22.33 (2.07) | 25.70 (2.20) | 0.59 | 6.73** | 3.57* |

| P-SCIP | 31.73 (1.85) | 24.25 (1.87) | 25.19 (2.01) | 21.26 (2.25) | (223) | (476) | (478) |

| Well-being | |||||||

| BPC | 41.07 (1.47) | 50.17 (1.47) | 50.23 (1.64) | 51.57 (1.73) | 0.08 | 15.86** | 0.61 |

| P-SCIP | 42.98 (1.45) | 50.33 (1.46) | 48.54 (1.60) | 49.81 (1.79) | (234) | (476) | (477) |

Note. dfdenom = degrees of freedom for denominator; BPC = best-practice psychosocial care; P-SCIP = parent social-cognitive intervention program.

p = .10.

p = .05.

p < .01.

Figure 2.

Interactions between treatment condition and time. P-SCIP = parent social-cognitive intervention program; BPC = best-practice psychosocial care.

Given the relative stability of outcomes across Time 2 to Time 4, the significant or marginally significant condition by time interactions for depression, anxiety, and distress were investigated using a simple interaction approach that systematically broke the 2 (treatment) by 4 (time) interaction into three sets of 2 (treatment) by 2 (time; Model 1 included Time 1 vs. 2, Model 2 included Time 2 vs. 3, and Model 3 included Time 3 vs. 4) ANOVA-type models. This approach allowed us to test whether the immediate effects of the treatment differed for the P-SCIP and BPC groups (i.e., from Time 1 to Time 2), and whether change across time differed by condition at the later times as well. As in the main analysis, the caregiver and child covariates were included in the models. The two-factor analyses including data from Times 1 and 2 yielded significant time by condition interactions for anxiety, F(1, 186) = 7.17, p = .008, and depression, F(1, 189) = 7.97, p = .005, but the interaction for traumatic distress was only marginally significant, F(1, 191) = 3.24, p = .074. As can be seen in the means for Time 1 and Time 2, anxiety dropped more in the P-SCIP condition (a drop of 4.99 points) than in the BPC condition (a drop of 1.79 points). Likewise, in P-SCIP depression dropped by 3.90 points but in BPC the drop was considerably smaller at 1.40 points. Although not significant, the pattern for traumatic distress was similar with BPC distress dropping 1.41 points as compared to a drop of 7.48 points in P-SCIP.

In the simple interactions testing condition effects across Times 2 and 3, significant simple interactions emerged for anxiety, F(1, 153) = 4.18, p = .043, and traumatic distress, F(1, 163) = 6.53, p = .012, but not for depression, F(1, 168) = 1.63, p = .203. As can be seen in the means for anxiety and traumatic distress in Table 2, the interactions indicated that anxiety and traumatic distress decreased significantly in the BPC condition (p = .010 and p = .002, respectively) between Time 2 and Time 3. These drops in the BPC condition show that caregivers in BPC dropped down to similar levels at Time 3 as the P-SCIP caregivers achieved at Time 2. Anxiety and traumatic distress showed nonsignificant increases for P-SCIP (both ps > .65). Finally, although there was no evidence of time by condition simple interaction for depression or anxiety between Time 3 and 4 (both ps > .30), there was an interaction for traumatic distress, F(1, 129) = 4.30, p = .040, such that distress increased somewhat (p = .13) in BPC and decreased somewhat (p = .16) in P-SCIP.

We examined whether the results changed when analyses included only P-SCIP participants who completed all five sessions (N = 72). The results were consistent with those based on the full sample in that there were no main effects for condition, but the time main effects emerged for all outcomes. The time by condition interaction for anxiety remained statistically significant (p = .007), and the time by condition interaction for depression became significant, F(3, 413) = 2.63, p = .050. However, the time by condition interaction for traumatic distress was only marginally significant, p = .092.

Moderator Effects

We evaluated Time 1 levels of distress (depression, anxiety, and traumatic distress) as possible moderators of the effects of condition and time on our four primary outcomes. We also examined optimism and three indicators of HSCT risk (GvHD present or not at transplant discharge, autologous or matched sibling allogeneic transplant vs. nonsibling donor allogeneic transplant, and malignancy vs. nonmalignant disease) as possible moderators. Initial depression scores showed a significant interaction with condition in predicting depression, b = −.089, t(243) = 2.10, p = .037. This interaction suggests that the average condition effect, averaging over time, is different for different levels of baseline depression. Simple slopes analyses were computed treating low initial depression as 1 SD below average and high initial depression as 1 SD above average. When initial depression was low, there was no evidence of a condition effect, b = .391, t(247) = 0.88, p = .378 (marginal means BPC M = 3.92, P-SCIP M = 4.70). However, when initial depression was high, there was evidence of a condition effect, b = −.990, t(241) = 2.15, p = .033. The estimated marginal means for depression when initial depression was high was M = 16.76 in BPC and M = 14.78 in P-SCIP. Therefore, among caregivers whose initial depression was high, P-SCIP resulted in lower average depression than BPC.

A similar interaction between initial depression and condition was marginally significant in predicting traumatic distress over time, b = −.214, t(225) = 1.80, p = .073. When initial depression was low there was no evidence of a condition effect, b = .724, t(229) = 0.58, p = .561 (marginal means BPC M = 22. 413, P-SCIP M = 23.86), but when initial depression was high there was some evidence of a condition effect, b = −2.61, t(224) = 2.02, p = .045. When initial depression was high, the estimated marginal mean for traumatic distress in BPC was M = 34.02 as compared to a mean of M = 28.80 in P-SCIP. Thus, when caregivers started treatment relatively high in depression, there is evidence that the P-SCIP treatment was more effective in reducing traumatic distress and depression as compared to BPC. Time 1 depression did not significantly moderate condition effects for anxiety or positive well-being. We also conducted a more targeted analysis examining long-term effects specifically by examining the condition by initial depression interactions predicting only the Time 4 outcomes, and no such interactions emerged suggesting the increased beneficial effect for P-SCIP relative to BPC for caregivers with elevated baseline depression was not a long-term effect.

When moderating effects of Time 1 anxiety were examined, initial anxiety did not moderate the effect of condition on depression or anxiety, but it did moderate the effect of condition on traumatic distress, b = −.203, t(237) = 2.24, p = .026. When baseline anxiety was 1 SD below average, there was no evidence of a difference in average traumatic distress as a function of condition, b = .907, t(231) = 0.75, p = .452 (marginal means BPC M = 22.21, P-SCIP M = 24.02). When initial anxiety was high, there was evidence of a condition effect, b = −3.059, t(238) = 2.37, p = .019. Specifically, when initial anxiety was high, individuals in the BPC condition had an average predicted traumatic distress of M = 32.80 over time and in the P-SCIP condition predicted average traumatic distress over time was M = 26.68. Notably, this pattern also emerged when only the Time 4 outcomes were considered, suggesting a long-term effect. That is, the condition by initial anxiety interaction was significant when predicting only the Time 4 traumatic distress, b = −.503, t(116) = 2.51, p = .014. When initial anxiety was low, there was no evidence of a condition effect, b = 1.933, t(116) = 0.78, p = .435, but when initial anxiety was high the condition effect was significant, b = −7.87, t(116) = 2.71, p = .008, such that P-SCIP resulted in significantly lower traumatic distress at Time 4 than did BPC. Baseline anxiety did not significantly moderate condition effects for depression, anxiety, or positive well-being. Time 1 traumatic distress did not moderate condition effects for any of the four outcomes.

Time 1 optimism, whether or not the child was transplanted for a malignancy, and the transplant donor type did not show any evidence of moderation of the condition effect or the time condition interaction. However, there was evidence of a significant interaction between condition and GvHD at discharge for anxiety, b = −1.53, t(167) = 2.21, p = .029, as well as a marginally significant interactions for depression, b = −1.12, t(188) = 1.91, p = .057, and traumatic distress, b = −2.16, t(208) = 1.79, p = .075. The estimated marginal means, standard errors, and t tests testing the condition effect for positive and negative GvHD are presented in Table 3. Caregivers of patients with GvHD showed significant (distress) or marginally significant (anxiety and depression) condition effects such that anxiety, depression, and traumatic distress were lower on average in P-SCIP relative to BPC. No significant condition effects emerged for caregivers of children who did not have GvHD.

Table 3.

Estimated Marginal Means and Standard Errors for Outcomes as a Function of Graft-Versus-Host Disease (GvHD) and Treatment Condition

| GvHD at discharge

|

Not diagnosed with GvHD at discharge

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | BPC (n = 17) M (SE) |

P-SCIP (n = 17) M (SE) |

Test of condition t (df) |

BPC (n = 81) M (SE) |

P-SCIP (n = 79) M (SE) |

Test of condition t (df) |

| Depression | 13.28 (1.64) | 9.35 (1.67) | 1.85† (185) | 8.09 (1.10) | 8.65 (1.11) | 0.58 (197) |

| Anxiety | 13.26 (1.93) | 8.60 (1.96) | 1.83† (165) | 7.44 (1.29) | 8.97 (1.29) | 1.31 (174) |

| Traumatic distress | 30.77 (3.40) | 22.08 (3.46) | 1.98* (205) | 25.84 (2.32) | 25.90 (2.32) | 0.02 (220) |

Note. BPC = best-practice psychosocial care; P-SCIP = parent social-cognitive intervention program.

p < .10.

p < .05.

When we examined the long-term effects of condition as a function of GvHD status by examining only outcomes at Time 4, marginally significant condition by GvHD interaction emerged for anxiety, b = −2.00, t(116) = 1.94, p = .055, and depression, b = −1.70, t(114) = 1.72, p = .087. Although neither of the simple effects of condition on anxiety for the two levels of GvHD attained statistical significance, the mean differences were in line with the overall analysis such that when the child had GvHD anxiety was lower in P-SCIP (M = 9.55) than in BPC (M = 14.63), and a smaller difference, favoring BPC (M = 5.94) relative to P-SCIP (M = 8.87) occurred when the child did not have GvHD. The results for depression paralleled those in the overall analysis such that the mean difference for depression when the child had GvHD showed that P-SCIP caregivers were lower in depression (M = 8.82) than BPC caregivers (M = 14.31). For caregivers of children without GvHD, depression levels were more similar across conditions (BPC = M 6.87, P-SCIP = M 8.17).

Mediation and Secondary Outcomes

Although analyses of the primary outcomes suggest that there were significant differences between P-SCIP and BPC, there were no main effects of condition. Instead, condition differences were moderated by time and other variables. The absence of a clear intervention main effect suggests that mediational analyses may be relatively uninformative. Therefore, instead of presenting complex mediated moderator analyses, we simply treated our potential mediator variables as secondary outcomes for which we examined condition and time effects.

Multilevel modeling was used to test mean differences as a function of condition and time while controlling for the set of caregiver and child covariates. Humor, F(1, 183) = 7.61, p = .006, and problem solving, F(1, 190) = 4.46, p = .036, showed statistically significant main effects of condition such that these two types of coping were higher on average in the P-SCIP condition (humor, M = 2.98; problem solving, M = 5.43) than in the BPC condition (humor, M = 2.52; problem solving, M = 4.95). A similar main effect of condition also emerged for acceptance, F(1, 188) = 5.50, p = .020, again with higher levels of acceptance in the P-SCIP condition (M = 13.61) relative to BPC (M = 12.79). Finally, with the exception of humor and the number of fears, all of the secondary outcomes showed significant main effects of time. Means, standard errors, and statistical tests for the full analyses of condition, time, and the condition by time interaction are available from the authors.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to examine the efficacy of a new intervention, P-SCIP, which was designed to reduce the psychological distress and improve the positive well-being of primary caregivers to children at the time of HSCT. P-SCIP targeted caregivers’ ability to use coping skills that have been shown to reduce caregiver distress in our prior work, and it was delivered during the HSCT hospitalization, which has been shown to be the most distressing time period for primary caregivers. Results indicated that the majority of caregivers attended at least three of the five sessions. P-SCIP was well-evaluated by the caregivers who participated in the sessions, both in terms of treatment evaluations and the working alliance with interventionists. The pattern of changes in caregiver psychological adjustment over time indicated that P-SCIP reduced anxiety, depression, and traumatic distress (marginally) more than BPC. However, the beneficial effects of P-SCIP as compared with BPC were more short-term than enduring. That is, the overall psychological benefits of P-SCIP relative to BPC were no longer evident at the 6 month or 1-year follow-ups, as psychological distress (specifically anxiety and traumatic distress) decreased significantly between Times 2 and 3 in BPC, and thus distress at Times 3 and 4 was very similar across conditions. Distress declined among all caregivers over the 1-year follow-up period, which is consistent with a wide body of research on the course of caregiver distress after pediatric HSCT (Barrera et al., 2012; Manne et al., 2004; Streisand et al., 2000; Phipps et al., 2004). For most caregivers, if their child survives, the medical treatment has succeeded, and elevations in distress drop once the child is medically stable. Compared with another study targeting caregivers to pediatric HSCT recipients, which did not show any effects on distress (Lindwall et al., 2014), our study suggests that P-SCIP had an impact when primary caregivers were experiencing the most trauma and stress—during the time of the actual HSCT.

Moderation analyses suggest that P-SCIP was more beneficial for specific subgroups of caregivers based on caregiver characteristics and transplant medical risk. P-SCIP was more effective in reducing traumatic distress among caregivers reporting more anxiety at baseline. These moderation effects were evident at the 1-year follow-up. P-SCIP was more effective in reducing depression and traumatic distress among caregivers who had higher depression at Time 1, but these effects were not enduring as they were not evident at the 1-year follow-up. For caregivers of children who were diagnosed with GvHD, two of the three distress outcomes, anxiety and depression, were marginally lower in P-SCIP than BPC at the 1-year follow-up.

In sum, P-SCIP offered immediate relief of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and traumatic distress as compared with a minimal, best-practice psychosocial care control treatment. It is important to note that P-SCIP showed long-term (one year) effects on traumatic stress symptoms among the caregivers who were most anxious before the HSCT, and P-SCIP had long-term effects on anxiety and depression reported by caregivers whose children had a severe and disabling transplant-related problem, GvHD. These results are consistent with other intervention studies suggesting that parent caregiver interventions are more effective among parents with fewer psychosocial resources (Sahler et al., 2005).

It is not clear why the benefits of the P-SCIP intervention peaked 6 months after intervention. The finding may reflect that distress declines among all caregivers over the first 6 months after HSCT as the child recovers and the medical outcome of the HSCT is shown, rather than indicating a diminished treatment response to P-SCIP. Nevertheless, the immediate relief offered by P-SCIP is important, because it spares caregivers additional stress and trauma during a universally stressful life experience. In addition, it offers long-term benefits for caregivers experiencing higher anxiety.

P-SCIP had a beneficial impact on several cognitive and social-processing strategies that were targeted in the sessions. Acceptance, humor, and problem-solving coping were significantly higher among caregivers enrolled in P-SCIP than caregivers enrolled in BPC. However, there were no effects noted for positive reappraisal, seeking emotional support, and fear appraisals, which were specifically focused on in P-SCIP sessions. Moreover, the findings for distraction coping were inconsistent. Overall, the findings suggested that P-SCIP impacted some, but not all, of the coping strategies we proposed it would affect. There has been very little work elucidating possible mechanisms for interventions for caregivers, with the exception of the Bright IDEAS Problem-Solving Skills Training (PSST; Sahler et al., 2013), which showed an impact of PSST on problem-solving skills as compared with a nondirective support intervention. These findings suggest that P-SCIP effected problem solving and humor coping, but not other skills which were targeted.

There are study limitations that should be considered. First, as we noted initially, there were more caregivers who did not complete the follow-up surveys in the P-SCIP condition at Times 2, 3, and 4 (due to reasons other than the child’s death) than in the BPC condition. Although the analyses included data on all participants, and there were no differences in baseline characteristics of participants who dropped out, it is still possible that the differential drop-out rate was an issue. There were also a number of P-SCIP caregivers who did not attend any sessions or one session (19%). This is a relatively high drop rate, which is understandable given the challenge of working with caregivers in the first week after the HSCT when many did not want to leave the child’s bedside. The drop-out rate from P-SCIP sessions may have biased the results and the potential beneficial impact of P-SCIP. The fact that our findings did not change when only caregivers who attended all sessions were analyzed suggests that this bias probably did not impact the findings. If this intervention is disseminated into clinical settings, methods of improving ease of attendance that do not require the parent leave the child’s bedside (e.g., Skype/Facetime or phone sessions) may prove useful. Third, we did not include a no-treatment control. It is possible, but not likely, that the declines in distress seen at the later follow-ups was due to the DVD and “Tips for Caregiver” handouts or to the supportive care services offered in the enriched environments of the pediatric units at these centers. Large and comprehensive treatment centers may not be representative of transplantation centers that may have fewer psychosocial and supportive care resources because they provide caregivers many supportive care services such as counseling, psychotropic medications, and integrative care (e.g., yoga, massage). Fourth, research staff who collected surveys were not blind to the study condition. Participant survey responses may have been influenced by research assistants. Finally, our sample included a very small number of fathers, and therefore we were unable to examine possible differences between mother and father as primary caregivers.

Overall, our results suggest that P-SCIP had short-term beneficial effect on caregiver distress during the HSCP hospitalization, when caregivers experience the most distress. Long-term beneficial effects on distress were seen among subgroups of caregivers, specifically those who began the HSCT hospitalization reporting higher levels of anxiety and among caregivers of children who developed GvHD during the hospitalization. These findings suggest that screening caregivers for elevations in anxiety and monitoring for adverse medical effects such as GvHD, and targeting interventions specifically to these caregivers, may prove beneficial.

What is the public health significance of this article?

A brief cognitive–behavioral intervention for caregivers of children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant reduced caregiver distress during the transplant hospitalization. Long-term effects on caregiver distress were found for more anxious caregivers as well as caregivers of children who developed graft-versus-host disease after the transplant.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Tara Bohn, Caraline Craig, Ayxa Calero-Breckeimer, Sara Frederick, Tina Gajda, Laura Goorin, Merav Ben Horin, Bonnie Maxson, Julia Randomski, Mirko Savone, Kristen Sorice, Kate Volipicelli, and Octavio Zavala. We thank the caregivers who participated, the pediatric HSCT teams at all sites, and the P-SCIP interventionists. Ernie Katz participated in this study for the first year.

This work was supported by Grant CA127488 awarded by the National Cancer Institute to Sharon Manne.

Contributor Information

Sharon Manne, Department of Medicine, Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

Abraham Bartell, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Laura Mee, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine.

Stephen Sands, Departments of Pediatrics and Psychiatry, Columbia University School of Medicine.

Deborah A. Kashy, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University

References

- Albrecht T, Burleson R, Goldsmith D. Supportive communication. In: Knapp M, Miller G, editors. Handbook of interpersonal communication. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 419–499. [Google Scholar]

- Alousi AM, Bolaños-Meade J, Lee SJ. Graft-versus-host disease: State of the science. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2013;19(Suppl):S102–S108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.10.028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aricò M, Schrappe M, Hunger SP, Carroll WL, Conter V, Galimberti S, Valsecchi MG. Clinical outcome of children with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated between 1995 and 2005. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:4755–4761. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Atenafu E, Doyle J, Berlin-Romalis D, Hancock K. Differences in mothers’ and fathers’ psychological distress after pediatric SCT: A longitudinal study. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2012;47:934–939. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2011.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Boyd Pringle LA, Sumbler K, Saunders F. Quality of life and behavioral adjustment after pediatric bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2000;26:427–435. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702527. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1702527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory–II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec T, Nau S. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(72)90045-6. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcot J, Norton S, Hunter MS. Cognitive behaviour therapy for menopausal symptoms following breast cancer treatment: Who benefits and how does it work? Maturitas. 2014;78:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.01.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M, Burgess P, Pattison P. Reaction to trauma: A cognitive processing model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:452–459. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.452. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.101.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuHamel KN, Manne S, Nereo N, Ostroff J, Martini R, Parsons S, Redd WH. Cognitive processing among mothers of children undergoing bone marrow/stem cell transplantation. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:92–103. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000108104.23738.04. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.PSY.0000108104.23738.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eduardo FP, Bezinelli LM, de Carvalho DL, Lopes RM, Fernandes JF, Brumatti M, Correa L. Oral mucositis in pediatric patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Clinical outcomes in a context of specialized oral care using low-level laser therapy. Pediatric Transplantation. 2015;19:316–325. doi: 10.1111/petr.12440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/petr.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry C, Gemayel G, Rocha V, Labopin M, Esperou H, Robin M, Socié G. Long-term outcomes after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for children with hematological malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2007;40:219–224. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705710. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1705710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze KE, Rodday AM, Nolan MJ, Bingen K, Kupst MJ, Patel SK, Parsons S. The impact of pediatric blood and marrow transplant on parents: Introduction of the Parent Impact scale. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015;13:46. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0240-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopko DR, Clark CG, Cannity K, Bell JL. Pretreatment depression severity in breast cancer patients and its relation to treatment response to behavior therapy. Health Psychology. 2016;35:10–18. doi: 10.1037/hea0000252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1989;36:223–233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223. [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R. Shattered assumptions. New York, NY: Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Kim Y, Kim J, Cho E, Lee E, Lee J, Yoo K. Neurologic complications after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children: Analysis of prognostic factors. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.02.007. in press. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore S. A social cognitive-processing model of emotional adjustment to cancer. In: Baum A, Andersen B, editors. Psychological interventions for cancer. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 99–116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10402-006. [Google Scholar]

- Lindwall JJ, Russell K, Huang Q, Zhang H, Vannatta K, Barrera M, Phipps S. Adjustment in parents of children undergoing stem cell transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20:543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.01.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Duhamel K, Ostroff J, Parsons S, Martini DR, Williams SE, Redd WH. Coping and the course of mother’s depressive symptoms during and after pediatric bone marrow transplantation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:1055–1068. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000070248.24125.C0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.CHI.0000070248.24125.C0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, DuHamel K, Ostroff J, Parsons S, Martini DR, Williams SE, Redd WH. Anxiety, depressive, and posttraumatic stress disorders among mothers of pediatric survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1700–1708. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1700. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.6.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Nereo N, DuHamel K, Ostroff J, Parsons S, Martini R, Redd WH. Anxiety and depression in mothers of children undergoing bone marrow transplant: Symptom prevalence and use of the Beck Depression and Beck Anxiety Inventories as screening instruments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:1037–1047. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1037. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne SL, Rubin S, Edelson M, Rosenblum N, Bergman C, Hernandez E, Winkel G. Coping and communication-enhancing intervention versus supportive counseling for women diagnosed with gynecological cancers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:615–628. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.615. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann I, Pearlman L. Psychological trauma and the adult survivor. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta P, Zhang M, Eapen M, He W, Seber A, Gibson B, Davies S. Transplant outcomes for children with hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.04.008. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins LL, Fedele DA, Chaffin M, Hullmann SE, Kenner C, Eddington AR, McNall-Knapp RY. A clinic-based interdisciplinary intervention for mothers of children newly diagnosed with cancer: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2012;37:1104–1115. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss093. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik P, Premsagar B, Mallikarjuna M. Acute renal failure in liver transplant patients: Indian study. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry. 2015;30:94–98. doi: 10.1007/s12291-013-0410-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12291-013-0410-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AE, Miles MS, Belyea MJ. Coping and support effects on mothers’ stress responses to their child’s hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 1997;14:202–212. doi: 10.1177/104345429701400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packman W, Weber S, Wallace J, Bugescu N. Psychological effects of hematopoietic SCT on pediatric patients, siblings and parents: A review. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2010;45:1134–1146. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2010.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker J, Harber K. A social stage model of collective coping: The Loma Prieta earthquake and the Persian Gulf War. Journal of Social Issues. 1993;49:125–145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb01184.x. [Google Scholar]

- Peters C, Schrappe M, von Stackelberg A, Schrauder A, Bader P, Ebell W, Klingebiel T. Stem-cell transplantation in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A prospective international multicenter trial comparing sibling donors with matched unrelated donors—The ALL-SCT-BFM-2003 trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33:1265–1274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.9747. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.9747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps S, Dunavant M, Lensing S, Rai SN. Patterns of distress in parents of children undergoing stem cell transplantation. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2004;43:267–274. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pbc.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimé B. Mental rumination, social sharing, and the recover from emotional exposure. In: Pennebaker J, editor. Emotion, disclosure, and health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995. pp. 271–291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10182-013. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue JR, MacNaughton K, Hoffmann RG, III, Graham-Pole J, Andres JM, Novak DA, Fennell RS. Transplantation in children. A longitudinal assessment of mothers’ stress, coping, and perceptions of family functioning. Psychosomatics. 1997;38:478–486. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71425-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahler OJ, Dolgin MJ, Phipps S, Fairclough DL, Askins MA, Katz ER, Butler RW. Specificity of problem-solving skills training in mothers of children newly diagnosed with cancer: Results of a multisite randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:1329–1335. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.1870. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahler OJ, Fairclough DL, Phipps S, Mulhern RK, Dolgin MJ, Noll RB, Butler RW. Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: Report of a multisite randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:272–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeant S, Mongrain M. Are positive psychology exercises helpful for people with depressive personality styles? The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2011;6:260–272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.577089. [Google Scholar]

- Sergeant S, Mongrain M. An online optimism intervention reduces depression in pessimistic individuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:263–274. doi: 10.1037/a0035536. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0035536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan A, Srinivasan S, Sunthankar S, Sunkara A, Kang G, Stokes DC, Leung W. Pre-hematopoietic stem cell transplant lung function and pulmonary complications in children. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2014;11:1576–1585. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201407-308OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201407-308OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streisand R, Rodrigue JR, Houck C, Graham-Pole J, Berlant N. Brief report: Parents of children undergoing bone marrow transplantation: Documenting stress and piloting a psychological intervention program. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2000;25:331–337. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.5.331. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/25.5.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait R, Silver RC. Coming to terms with major negative life events. In: Uleman JS, Bargh JA, editors. Unintended thought. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1989. pp. 351–382. [Google Scholar]

- Terrin N, Rodday AM, Tighiouart H, Chang G, Parsons SK, the Journeys to Recovery Study Parental emotional functioning declines with occurrence of clinical complications in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21:687–695. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1566-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1566-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veit CT, Ware JE., Jr The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51:730–742. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.5.730. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijmoet-Wiersma CM, Egeler RM, Koopman HM, Bresters D, Norberg AL, Grootenhuis MA. Parental stress and perceived vulnerability at 5 and 10 years after pediatric SCT. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2010;45:1102–1108. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2009.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]