Abstract

High altitude polycythemia (HAPC) refers to the long-term living in the plateau of the hypoxia environment is not accustomed to cause red blood cell hyperplasia. The pathological changes are mainly the various organs and tissue congestion, blood stasis and hypoxia damage. Although chronic hypoxia is the main cause of HAPC, the related molecular mechanisms remain largely unclear. This study aims to explore the genetic basis of HAPC in the Chinese Han and Tibetan populations. We enrolled 100 patients (70 Han, 30 Tibetan) with HAPC and 100 healthy control subjects (30 Han, 70 Tibetan). To explore the hereditary basis of HAPC and investigate the association between EPHA2 with AGT and HAPC in Chinese Han and Tibetan populations. Using the Chi-squared test and analyses of genetic models, rs2291804, rs2291805, rs3768294, rs3754334, rs6603856, rs6669624, rs11260742, rs13375644 and rs10907223 in EPHA2, and rs699, rs4762 and rs5051 in AGT showed associations with reduced HAPC susceptibility in Han populations. Additionally, in Tibetan populations, rs2478523 in AGT showed an increased the risk of HAPC. Our study suggest that polymorphisms in the EPHA2 and AGT correlate with susceptibility to HAPC in Chinese Han and Tibetan populations.

Keywords: high altitude polycythemia, EPHA2, AGT, gene polymorphisms, case-control study

INTRODUCTION

HAPC is an increased number of circulating erythrocytes develop in high altitude dwellers to compensate for high altitude associated hypoxia. The clinical diagnosis of HAPC requires a hemoglobin concentration ≥ 190 g/L for female or ≥ 210 g/L for men, and accompanied by the following three or more symptoms: dyspnea, palpitations, sleep disorders, venous dilatation, headache and tinnitus. Compared with the same altitude of healthy people, HAPC patients with red blood cells, hemoglobin and erythrocyte volume was significantly increased and oxygen saturation was decreased. Most people occur at an altitude of more than 3200 m area, but there are a few patients can occur in less than 3200 m area. The incidence of HAPC in the Tibetan Plateau is 5% to 18% [1], and the incidence of HAPC increases as the altitude increases, which is a serious public health problem in China and other Andean countries [2]. It is known that hypobaric hypoxia is the main reason for the change of pathophysiology in high altitude area, and the physiological changes of the plateau acclimatization involve oxygen intake, transportation and utilization [3]. However, there is no effective prevention or treatment measures to deal with this disease because the pathogenesis is poorly understood. The incidence of HAPC in Europe is higher than the Andean groups, and the incidence of HAPC in Andean populations is higher than the Chinese Tibetan populations who living at the same altitude. Simonson et al. [4] found the hemoglobin concentrations were significantly associated with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of several genes in Tibetan populations, these results suggest that HAPC presents obvious racial and significant individual differences in susceptibility.

HAPC mainly leads to a significant increase in blood viscosity, causing damage to microcirculatory disturbances, vascular thrombosis, extensive organ damage, sleep disorders, and death [5]. The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is the world's highest plateau, with an average elevation of more than 4000 meters. Most of the Tibetan people reside at altitude of 3000 m to 4500 m for a long time. Due to heritable adaptations, so they can better adapt to the hypoxia environment, as indicated by lower hemoglobin levels, lower hematocrit, higher oxygen saturation and other characteristics to help them better adapt to the plateau hypoxia environment. However, despite these genetic adaptability, the Tibetan populations still develop into HAPC in plateau area [6]. Several studies have shown that both the permanent high altitude natives and migrants show susceptibility to HAPC in the plateau, but the prevalence of HAPC among migrants was significantly higher. It is mainly due to the significant differences in the genome of the two groups, suggesting that genetic factors may contribute to the development of HAPC. Although early studies have reported the genetic basis of HAPC, only some of these genetic factors have been reported, and most studies have focused on high-altitude populations and genes involved in the hypoxia-inducible factor pathway. Growing evidence suggests that the positive directional selection of genes such as EPAS1, EGLN1, CARD14, SENP1, and VEGFA plays an important role in the adaptation of permanent high altitude natives and migrants [7–9]. Furthermore, we also found several genes and loci which were located chromosome 1. These genes are significantly associated with the susceptibility to HAPC, especially in the hypoxia environment of the permanent high altitude natives and migrants.

In this study, we discovered that EPHA2, a member of the large family of ephrin receptor tyrosine kinases, helps to maintain epidermal tissue homeostasis. EPHA2 is overexpressed in tumors and promotes metastasis by stimulating cell migration and angiogenesis. In addition, the maintenance of genomic stability is critical to the development of organisms and the prevention of disease. Huynh-Do et al. [10] took advantage of an established model of kidney infarction to describe the effect of local renal hypoxia on EPHA2 and erythropoietin (EPO) regulation. They found EPHA2 increases tubular cell attachment, laminin secretion and modulates EPO expression after renal hypoxia injury. EPO is a hormone that increases the amount of red blood cells and increases the oxygen content of the blood in the human body. It contains a certain amount in the normal human body to maintain and promote normal erythrocyte metabolism. The AGT (rs699) genotyping of the M235T polymorphism was associated with chronic mountain sickness (CMS) in Tibetan populations living between 3600 and 4400 m, it was significantly associated with oxygen saturation in CMS patients [11]. Gao et al. [9] reported that AGT 235M allele showed a significant association with risk of HAPC development in Tibetans. Here, we conducted a case-control study to investigate the association of these genes variants with HAPC in Chinese Han and Tibetan populations.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the basic information of cases and controls groups. The basic information of candidate SNPs in Han and Tibetan subjects were summarized in Table 2 and Table 3. The location information of candidate SNPs in the case and control groups were presented in Table 4. In Han populations, we found that the rs2291804 (OR = 0.137, 95% CI = 0.035-0.536, p = 0.001), rs2291805 (OR = 0.293, 95% CI = 0.129-0.665, p = 0.002), rs3768294 (OR = 0.291, 95% CI = 0.131-0.647, p = 0.002), rs3754334 (OR = 0.402, 95% CI = 0.192-0.840, p = 0.014), rs6603856 (OR = 0.321, 95% CI = 0.140-0.737, p = 0.006), rs6669624 (OR = 0.359, 95% CI = 0.150-0.856, p = 0.017), rs11260742 (OR = 0.344, 95% CI = 0.155-0.761, p = 0.007), rs13375644 (OR = 0.296, 95% CI = 0.123-0.713, p = 0.005) and rs10907223 (OR = 0.354, 95% CI = 0.152-0.821, p = 0.013) in EPHA2 were significantly associated with decreased HAPC risk. Furthermore, the rs699 (OR = 0.446, 95% CI = 0.222-0.897, p = 0.022), rs4762 (OR = 0.253, 95% CI = 0.091-0.701, p = 0.005) and rs5051 (OR = 0.413, 95% CI = 0.207-0.826, p = 0.011) in AGT gene were associated with decreased HAPC susceptibility. Similarly, in Tibetan populations, the rs2478523 (OR = 2.629, 95% CI = 1.005-6.876, p = 0.043) in AGT were associated with increased HAPC susceptibility.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of the control individuals and patients with high altitude polycythemia.

| Variables | Han | Tibetan | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case (n=70) | Control (n=30) | Case (n=70) | Control (n=30) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 35 | 15 | 35 | 15 |

| Female | 35 | 15 | 35 | 15 |

Table 2. Basic information of candidate SNPs in Han subjects.

| SNP_ID | Gene | Alleles A/B | Case (N) | HWE Case | Control (N) | HWE Control | OR (95% CI) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AB | BB | AA | AB | BB | |||||||

| rs2230597 | EPHA2 | G/A | 4 | 21 | 45 | 0.470 | 3 | 5 | 22 | 0.106 | 1.422(0.627-3.229) | 0.398 |

| rs6678616 | C/T | 0 | 4 | 66 | 1.000 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 1.000 | 0.312(0.081-1.206) | 0.076 | |

| rs2291804 | C/T | 0 | 3 | 67 | 1.000 | 1 | 8 | 21 | 1.000 | 0.137(0.035-0.536) | 0.001 | |

| rs35127370 | C/T | 0 | 13 | 57 | 1.000 | 1 | 7 | 22 | 1.000 | 0.746(0.281-1.976) | 0.554 | |

| rs2291805 | C/T | 0 | 13 | 57 | 1.000 | 2 | 13 | 15 | 0.636 | 0.293(0.129-0.665) | 0.002 | |

| rs3768294 | G/A | 0 | 14 | 56 | 1.000 | 2 | 14 | 14 | 0.390 | 0.291(0.131-0.647) | 0.002 | |

| rs6678618 | C/T | 0 | 4 | 66 | 1.000 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 1.000 | 0.311(0.080-1.260) | 0.076 | |

| rs6603883 | G/A | 1 | 17 | 52 | 1.000 | 1 | 8 | 21 | 1.000 | 0.981(0.403-2.388) | 0.967 | |

| rs3754334 | G/A | 0 | 20 | 50 | 0.337 | 2 | 15 | 13 | 0.370 | 0.402(0.192-0.840) | 0.014 | |

| rs6603856 | G/A | 0 | 13 | 57 | 1.000 | 2 | 12 | 16 | 1.000 | 0.321(0.140-0.737) | 0.006 | |

| rs6669624 | G/A | 0 | 12 | 58 | 1.000 | 2 | 10 | 18 | 1.000 | 0.359(0.150-0.856) | 0.017 | |

| rs11260742 | T/C | 1 | 13 | 56 | 0.568 | 3 | 11 | 16 | 1.000 | 0.344(0.155-0.761) | 0.007 | |

| rs13375644 | C/T | 3 | 14 | 53 | 1.000 | 4 | 11 | 15 | 1.000 | 0.296(0.123-0.713) | 0.005 | |

| rs10907223 | G/A | 0 | 13 | 57 | 1.000 | 2 | 11 | 17 | 1.000 | 0.354(0.152-0.821) | 0.013 | |

| rs699 | AGT | G/A | 1 | 23 | 46 | 0.680 | 2 | 17 | 11 | 0.198 | 0.446(0.222-0.897) | 0.022 |

| rs11122576 | T/C | 7 | 35 | 28 | 0.600 | 3 | 10 | 17 | 0.644 | 1.692(0.845-3.389) | 0.135 | |

| rs5046 | G/A | 3 | 25 | 42 | 1.000 | 1 | 8 | 21 | 1.000 | 1.778(0.763-4.143) | 0.179 | |

| rs3789679 | G/A | 7 | 37 | 26 | 0.594 | 3 | 10 | 17 | 0.604 | 1.846(0.904-3.769) | 0.090 | |

| rs1926722 | C/A | 11 | 31 | 28 | 0.617 | 3 | 12 | 15 | 0.662 | 1.469(0.759-2.844) | 0.252 | |

| rs4762 | G/A | 1 | 5 | 64 | 0.146 | 2 | 8 | 20 | 1.000 | 0.253(0.091-0.701) | 0.005 | |

| rs28730748 | G/A | 3 | 6 | 61 | 0.196 | 1 | 7 | 22 | 1.000 | 0.455(0.157-1.321) | 0.140 | |

| rs2071406 | A/G | 1 | 19 | 50 | 1.000 | 2 | 8 | 20 | 1.000 | 0.847(0.372-1.931) | 0.693 | |

| rs5050 | T/G | 1 | 13 | 56 | 0.568 | 2 | 8 | 20 | 1.000 | 0.576(0.242-1.37) | 0.208 | |

| rs11122575 | A/G | 8 | 15 | 47 | 0.000 | 2 | 10 | 18 | 1.000 | 1.277(0.554-2.942) | 0.565 | |

| rs3827749 | G/A | 3 | 28 | 39 | 0.744 | 3 | 14 | 13 | 1.000 | 0.609(0.313-1.185) | 0.143 | |

| rs5051 | T/C | 1 | 23 | 46 | 0.680 | 2 | 16 | 12 | 0.413 | 0.413(0.207-0.826) | 0.011 | |

| rs11568020 | C/T | 0 | 7 | 63 | 1.000 | 0 | 2 | 28 | 1.000 | 3.000(0.361-24.95) | 0.287 | |

| rs2478523 | A/G | 8 | 28 | 19 | 0.782 | 5 | 13 | 12 | 1.000 | 0.841(0.431-1.638) | 0.610 | |

SNP: Single-nucleotide polymorphism; OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium;

Site with HWE p≤0.05 excluded; p<0.05 indicates statistical significance for allele model.

Table 3. Basic information of candidate SNPs in Tibetan subjects.

| SNP_ID | Gene | Alleles A/B | Case (N) | HWE Case | Control (N) | HWE Control | OR (95% CI) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AB | BB | AA | AB | BB | |||||||

| rs2230597 | EPHA2 | G/A | 0 | 22 | 48 | 0.195 | 0 | 9 | 21 | 1.000 | 1.056(0.455-2.453) | 0.898 |

| rs6678616 | C/T | 0 | 3 | 67 | 1.000 | 0 | 2 | 28 | 1.000 | 0.635(0.103-3.901) | 0.621 | |

| rs2291804 | C/T | 0 | 2 | 68 | 1.000 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 1.000 | 0.264(0.198-3.578) | 0.352 | |

| rs35127370 | C/T | 0 | 14 | 56 | 1.000 | 0 | 6 | 24 | 1.000 | 1.000(0.365-2.74) | 1.000 | |

| rs2291805 | C/T | 1 | 10 | 59 | 0.402 | 1 | 4 | 25 | 0.241 | 0.844(0.301-2.364) | 0.746 | |

| rs3768294 | G/A | 3 | 13 | 54 | 0.480 | 3 | 4 | 23 | 0.257 | 0.910(0.328-2.53) | 0.857 | |

| rs6678618 | C/T | 0 | 3 | 67 | 1.000 | 0 | 2 | 28 | 1.000 | 0.635(0.103-3.901) | 0.621 | |

| rs6603883 | G/A | 0 | 18 | 52 | 0.588 | 0 | 8 | 22 | 1.000 | 0.959(0.392-2.344) | 0.927 | |

| rs3754334 | G/A | 1 | 17 | 52 | 1.000 | 1 | 7 | 22 | 0.505 | 0.890(0.377-2.098) | 0.790 | |

| rs6603856 | G/A | 2 | 12 | 56 | 0.519 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 0.325 | 0.855(0.327-2.238) | 0.749 | |

| rs6669624 | G/A | 4 | 12 | 54 | 1.000 | 1 | 3 | 26 | 0.165 | 1.100(0.370-3.275) | 0.864 | |

| rs11260742 | T/C | 2 | 11 | 57 | 0.162 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 0.325 | 0.910(0.350-2.356) | 0.844 | |

| rs13375644 | C/T | 3 | 18 | 49 | 0.048 | 3 | 5 | 22 | 0.121 | 1.150(0.343-3.86) | 0.821 | |

| rs10907223 | G/A | 1 | 12 | 57 | 0.514 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 0.325 | 0.841(0.321-2.202) | 0.725 | |

| rs699 | AGT | G/A | 7 | 28 | 35 | 0.776 | 2 | 16 | 12 | 0.423 | 0.857(0.449-1.637) | 0.640 |

| rs11122576 | T/C | 5 | 33 | 32 | 0.573 | 2 | 14 | 14 | 0.688 | 1.034(0.535-1.999) | 0.920 | |

| rs5046 | G/A | 0 | 13 | 57 | 1.000 | 0 | 7 | 23 | 1.000 | 0.775(0.293-2.051) | 0.607 | |

| rs3789679 | G/A | 4 | 28 | 38 | 1.000 | 3 | 10 | 17 | 0.644 | 1.027(0.501-2.106) | 0.942 | |

| rs1926722 | C/A | 5 | 30 | 35 | 0.777 | 2 | 14 | 14 | 0.688 | 0.933(0.481-1.811) | 0.838 | |

| rs4762 | G/A | 0 | 6 | 64 | 1.000 | 0 | 3 | 27 | 1.000 | 0.851(0.206-3.52) | 0.823 | |

| rs28730748 | G/A | 2 | 12 | 56 | 0.519 | 2 | 10 | 18 | 0.553 | 0.519(0.216-1.251) | 0.139 | |

| rs2071406 | A/G | 2 | 26 | 42 | 0.720 | 1 | 9 | 20 | 1.000 | 1.215(0.563-2.62) | 0.619 | |

| rs5050 | T/G | 1 | 7 | 62 | 0.240 | 0 | 6 | 24 | 1.000 | 0.618(0.210-1.822) | 0.380 | |

| rs11122575 | A/G | 4 | 16 | 40 | 0.397 | 4 | 6 | 20 | 1.000 | 1.528(0.576-4.051) | 0.392 | |

| rs3827749 | G/A | 1 | 31 | 38 | 0.093 | 2 | 10 | 18 | 0.632 | 1.013(0.496-2.07) | 0.971 | |

| rs5051 | T/C | 7 | 30 | 33 | 1.000 | 2 | 16 | 12 | 0.423 | 0.917(0.481-1.746) | 0.791 | |

| rs11568020 | C/T | 1 | 1 | 68 | 0.022 | 0 | 2 | 28 | 1.000 | 0.635(0.103-3.901) | 0.621 | |

| rs2478523 | A/G | 6 | 30 | 34 | 1.000 | 3 | 12 | 15 | 0.034 | 2.629(1.005-6.876) | 0.043 | |

SNP: Single-nucleotide polymorphism; OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium;

Site with HWE p≤0.05 excluded; p<0.05 indicates statistical significance for allele model.

Table 4. Location information of candidate SNPs in this study.

| SNP_ID | Gene | Region | Position | MAF (Han) | MAF (Tibetan) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | ||||

| rs2230597 | exonic | 16464673 | 0.207 | 0.155 | 0.157 | 0.150 | |

| rs6678616 | exonic | 16475123 | 0.029 | 0.086 | 0.021 | 0.033 | |

| rs2291804 | intronic | 16464936 | 0.021 | 0.138 | 0.014 | 0.000 | |

| rs35127370 | intronic | 16474840 | 0.093 | 0.121 | 0.100 | 0.100 | |

| rs2291805 | intronic | 16458814 | 0.093 | 0.259 | 0.086 | 0.100 | |

| rs3768294 | intronic | 16456176 | 0.100 | 0.276 | 0.099 | 0.107 | |

| rs6678618 | EPHA2 | exonic | 16475126 | 0.029 | 0.086 | 0.021 | 0.033 |

| rs6603883 | upstream | 16482976 | 0.136 | 0.138 | 0.129 | 0.133 | |

| rs3754334 | exonic | 16451767 | 0.143 | 0.293 | 0.136 | 0.150 | |

| rs6603856 | intronic | 16460840 | 0.093 | 0.241 | 0.101 | 0.117 | |

| rs6669624 | intronic | 16460339 | 0.086 | 0.207 | 0.091 | 0.083 | |

| rs11260742 | intronic | 16464260 | 0.107 | 0.259 | 0.107 | 0.117 | |

| rs13375644 | intronic | 16461833 | 0.086 | 0.241 | 0.091 | 0.080 | |

| rs10907223 | exonic | 16459745 | 0.093 | 0.224 | 0.100 | 0.117 | |

| rs699 | exonic | 230845794 | 0.179 | 0.328 | 0.300 | 0.333 | |

| rs11122576 | intronic | 230846679 | 0.350 | 0.241 | 0.307 | 0.300 | |

| rs5046 | upstream | 230850398 | 0.221 | 0.138 | 0.093 | 0.117 | |

| rs3789679 | intronic | 230849694 | 0.358 | 0.232 | 0.246 | 0.241 | |

| rs1926722 | intronic | 230840197 | 0.379 | 0.293 | 0.286 | 0.300 | |

| rs4762 | exonic | 230845977 | 0.050 | 0.172 | 0.043 | 0.050 | |

| rs28730748 | AGT | intronic | 230845571 | 0.059 | 0.121 | 0.101 | 0.179 |

| rs2071406 | upstream | 230850641 | 0.150 | 0.172 | 0.214 | 0.183 | |

| rs5050 | UTR5 | 230849886 | 0.107 | 0.172 | 0.064 | 0.100 | |

| rs11122575 | intronic | 230840269 | 0.211 | 0.173 | 0.186 | 0.130 | |

| rs3827749 | intronic | 230841559 | 0.243 | 0.345 | 0.236 | 0.233 | |

| rs5051 | UTR5 | 230849872 | 0.179 | 0.345 | 0.314 | 0.333 | |

| rs11568020 | UTR5 | 230850018 | 0.050 | 0.017 | 0.021 | 0.033 | |

| rs2478523 | intronic | 230841509 | 0.400 | 0.442 | 0.330 | 0.158 | |

MAF: minor allele frequency

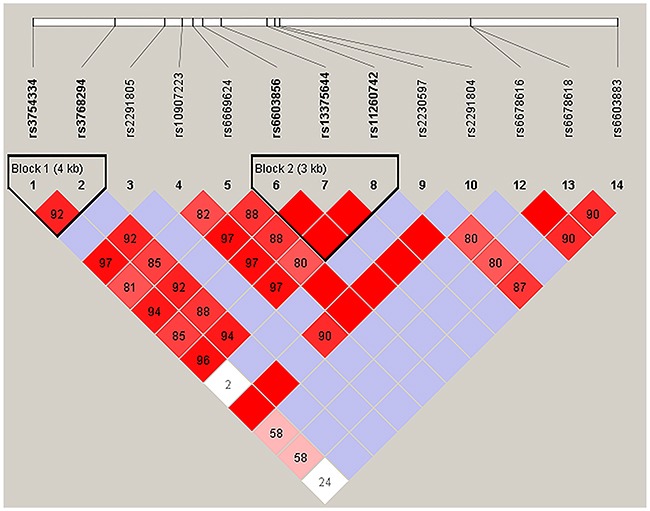

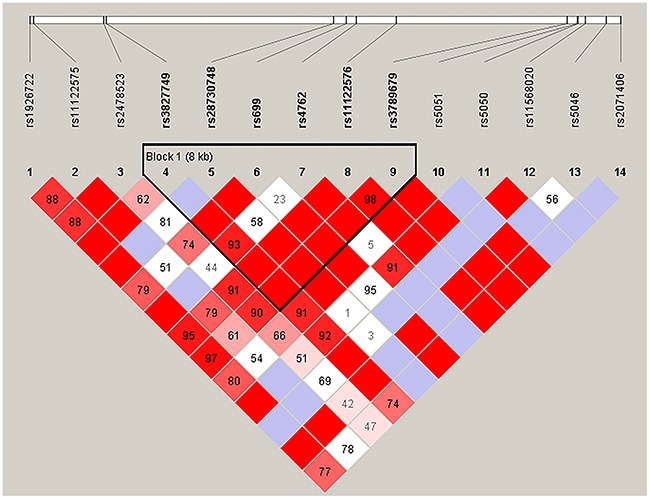

We further analyzed the association between SNPs and HAPC risk by unconditional logistic regression analysis using three models (dominant, recessive and additive) in Han and Tibetan populations (Tables 5 and 6). After stratifying by gender, we found the rs2291805 (p = 0.024, p = 0.014), rs3754334 (p = 0.046, p = 0.025) and rs13375644 (p = 0.034, p = 0.018) in EPHA2, the rs699 (p = 0.032, p = 0.038), rs4762 (p = 0.023, p = 0.030) and rs5051 (p = 0.032, p = 0.021) in AGT were associated with a decreased risk of HAPC based on analysis using the dominant and additive model, and the rs3789679 was associated with a reduced risk of HAPC in the dominant model. Moreover, in Tibetan populations, we found the re2478523 in AGT (p = 0.016) was associated with an increased risk of HAPC in the dominant model. Furthermore, using haplotype analysis, two blocks were detected among the EPHA2 SNPs (Figure 1). Block 1 contains rs3754334 and rs3768294, block 2 contains rs6603856, rs13375644 and rs11260742. And one block was detected among the AGT SNPs (Figure 2), block 1 contains rs3827749, rs28730748, rs699, rs4762, rs11122576 and rs3789679. The candidate SNPs in these genes showed strong linkages in subjects.

Table 5. Single loci associations with high altitude polycythemia risk in Han subjects.

| SNP_ID | Model | Ref Allele | Alt Allele | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2291805 | Dominant | 0.318 | 0.118-0.859 | 0.024 | ||

| Recessive | C | T | 0.245 | 0.095-0.629 | 0.999 | |

| Additive | 0.308 | 0.121-0.784 | 0.014 | |||

| rs3754334 | Dominant | 0.385 | 0.151-0.982 | 0.046 | ||

| Recessive | G | A | 0.436 | 0.140-0.857 | 0.999 | |

| Additive | 0.361 | 0.148-0.878 | 0.025 | |||

| rs13375644 | Dominant | 0.316 | 0.109-0.915 | 0.034 | ||

| Recessive | C | T | 0.452 | 0.102-0.779 | 0.999 | |

| Additive | 0.303 | 0.113-0.818 | 0.018 | |||

| rs699 | Dominant | 0.360 | 0.142-0.917 | 0.032 | ||

| Recessive | G | A | 0.524 | 0.027-10.32 | 0.671 | |

| Additive | 0.403 | 0.171-0.952 | 0.038 | |||

| rs3789679 | Dominant | 2.683 | 1.022-7.043 | 0.045 | ||

| Recessive | G | A | 1.869 | 0.329-10.6 | 0.480 | |

| Additive | 2.088 | 0.956-4.561 | 0.065 | |||

| rs4762 | Dominant | 0.248 | 0.074-0.826 | 0.023 | ||

| Recessive | G | A | 0.25 | 0.015-4.249 | 0.338 | |

| Additive | 0.331 | 0.122-0.898 | 0.030 | |||

| rs5051 | Dominant | 0.36 | 0.141-0.916 | 0.032 | ||

| Recessive | T | C | 0.182 | 0.014-2.316 | 0.189 | |

| Additive | 0.377 | 0.165-0.862 | 0.021 |

OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; p<0.05 indicates statistical significance for genetic model.

Table 6. Single loci associations with high altitude polycythemia risk in Tibetan subjects.

| SNP_ID | Model | Ref Allele | Alt Allele | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2478523 | Dominant | 4.533 | 1.325-15.500 | 0.016 | ||

| Recessive | A | G | 1.095 | 0.200-5.988 | 0.917 | |

| Additive | 2.386 | 0.937-6.079 | 0.068 |

OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; p<0.05 indicates statistical significance for genetic model.

Figure 1. Haplotype block map for the fourteen EPHA2 SNPs genotype in this study.

Figure 2. Haplotype block map for the fourteen AGT SNPs genotype in this study.

DISCUSSION

The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is the largest and highest plateau in the world, which includes the largest high altitude area population. Since the Qinghai-Tibetan railway went into service, more and more Han individuals from the plain into the plateau region, the incidence of HAPC increased by 21% in Han migrants [14]. Inspired by genome research and genetic mechanism of high altitude natives, we assume that genetic factors may be involved in the pathogenesis of HAPC in Han migrants. HAPC is a serious disease in the high altitude region, especially those who have emigrated from plain area into the high altitude area. In general, the incidence of HAPC increases with the elevation of altitude. The main cause of HAPC is chronic hypoxia in the high altitude environment [15], so it is necessary to investigate the genetic basis of HAPC. Our study revealed an association between SNPs in EPHA2, AGT and HAPC in the Chinese Han and Tibetan populations. Previous studies have shown the obvious differences in the incidences of HAPC among different groups, such as Han, Tibetan and Andean populations [16]. These results suggest that HAPC has a complex pathogenesis, resulting from the interaction of environmental and genetic factors. We studied SNPs on 28 loci to be associated with an increased or decreased risk for HAPC, and were able to show statistically significant results for them.

EPHA2 is a receptor tyrosine kinase that plays a key role in cell structure, migration and survival, upon juxtacrine contact with its membrane-bound ligand EphrinA1. In hypoxia environment, EPHA2 is upregulated in cortical and medullary tubular cells, while EphrinA1 was upregulated in the interstitial cells adjacent to the peritubular capillaries [17, 18]. In addition, EPO messenger RNA (mRNA) was strongly expressed in the border area of the infarcted kidney within the first 6 hours. Rodriguez et al. [10] activated the signaling pathway in vitro using recombinant EphrinA1/Fc or EPHA2/Fc proteins. Stimulation of EPHA2 positive signaling in the proximal tubular cell line HK2 increased basal-lateral cell attachment and protein secretion. In contrast, activation of reverse signalling through EphrinA1 expressed by Hep3B cells promoted EPO production at transcription and protein levels. Remarkably, intimate contact of Madin Darby Canine Kidney cells (the expression product of EPHA2) and Hep3B (the expression product of EphrinA1) are sufficient to induce a significant increase in EPO mRNA production in cells, even under hypoxia conditions. The synergistic effect of EPHA2 and hypoxia results in a 15-20-fold increase in EPO expression [19]. EPO production is mainly in the kidney and liver to regulate erythrocytosis. In addition to the kidney and liver, but also the myocardium, brain and bone marrow and other organizations can detect EPO mRNA. EPO plays an important role in erythropoiesis and heart development. Moreover, EPO can prevent cardiomyocyte hypoxia-induced apoptosis. Klopsch et al. [20] showed that intracardiac injection of EPO can improve cardiac output and ejection fraction in a rat myocardial infarction model. Brunner et al. [21] reported that EPO enhanced migration of stem cells into ischemic myocardium and this was mediated through upregulation of SDF-1 expression and SDF-1/CXCR-4 pathway. Hypoxia increases the expression of EPO by HIF-1α. The most striking changes in the expression of EPHA2 protein in acute hypoxia conditions occur in the renal medullary border, and hypoxia induced EPO expression was associated with EPHA2 protein. EPO produced by the liver during the fetus and EPO produced by the adult kidney is identified as an inducer of erythropoiesis by stimulating erythrocytes from bone marrow differentiation precursors. EPO can promote excessive cell production, so EPHA2 have a significant influence for the production of red blood cells.

AGT is an important candidate gene of the HAPC which has been shown to play a crucial role in CMS. The AGT gene (rs699) is located at chromosome 1 and consists of five exons, and it has more than 23 variants. The common polymorphism of the AGT gene is 235M, which encodes threonine instead of methionine at position 235 in exon 2. Gao et al. [22] reported AGT M235T (rs699) allele was associated with HAPC susceptibility in Chinese Tibetans, the specific genetic mechanism and biological functions has not been reported. However, we did not find this result in both Han and Tibetan populations. It has been also reported the AGT rs699 was associated with CMS in a Han Chinese population, although the description of CMS diagnosis is not clear and seems to include various disease [11]. Their results also show that the rs699 was significantly associated with the physiological parameters oxygen saturation and blood pressure among the Han Chinese populations. On the contrary, Koehle and Kalson et al. did not find this result in Nepalese and European groups, respectively [23, 24]. In addition, a significantly higher incidence of rs699 allele has been associated with atrial fibrillation in Taiwan aborigines [25]. Meanwhile, renin-angiotensin system (RAS) affects physiological and pathological effects of blood production, especially erythropoiesis. It has been reported up-regulation of local RAS, together with down-regulation of the cell surface angiotensin-converting enzyme receptors, in the autonomous neoplastic clonal erythropoiesis. The RAS was initially postulated to influence erythropoiesis following the demonstration of the haematopoietic side effects of RAS blockers [26]. Previous studies have shown the expression of angiotensin I-converting enzyme in normal erythropoietic cells and myeloproliferative bone marrow. There are several evidences suggesting the existence of local hematopoietic bone marrow RAS which contributes to the regulation of normal and disturbed hematopoiesis. So far, AGT has been detected in bone marrow where Ang II directly stimulates erythropoiesis through AT2R1 [27]. Based on the results of these previous studies and our research, AGT was significantly associated with erythropoiesis, especially in hypoxia state.

Tibet is a plateau region in Central Asia and the home to the indigenous Tibetan individuals. Tibet, an average elevation of 4900 meters, it is the highest region on earth and is commonly referred to as the “Roof of the World”. Tibetan has a unique genetic background, dietary and lifestyle habits. It has been suggested that several genetic polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to HAPC, whereas each polymorphism may contribute to only a small relative risk of HAPC involves a complex interplay between exposure to multiple environmental stimuli and genetic background. As a unique geological condition in Central Asia, due to the difference between the area and the dietary habit, Han population has another lifestyle. This is probably the main reason for differences between Tibetan and Han populations in hereditary diseases. Although there are important discoveries revealed by the studies, there are also limitations. On the one hand, due to practical constraints, this paper cannot provide enough sample size for correlation studies. On the other hand, the functions of the genetic variants and their mechanisms have not been evaluated in this study.

CONCLUSION

We analyzed SNPs in the EPHA2 and AGT genes and identified a relationship between genetic polymorphisms and HAPC in Chinese Han and Tibetan populations. This study set out to determine paramount insights into the etiology of HAPC. However, additional genetic risk factors and functional investigations should be identified confirm our results. Finally, areas for further research are identified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

After obtaining written informed consent, a total of 200 individuals from the Second People’s Hospital of Tibet Autonomous Region and Tibet military region general hospital in this study. All subjects were residing at an altitude above 4000 m for at least 3 months. According to the diagnostic criteria of CMS, we selected HAPC patients with excessive polycythemia (male, hemoglobin ≥ 210 g/L; female, hemoglobin ≥ 190 g/L) and without high altitude cerebral edema and high-altitude pulmonary edema. In addition, subjects with endocrinological, nutritional and metabolic diseases that would worsen upon hypoxemia were excluded. Healthy subjects in age and gender were randomly selected from a physical examination at an outpatient clinic to serve as controls. This research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Xizang Minzu University.

Epidemiological and clinical data

We collected demographic and clinical data using a standardized epidemiological questionnaire, including information on age, gender, ethnicity, residential region, education status, family history of cancer. Furthermore, the case information was collected through consultation with treating physicians or from medical chart review, including blood oxygen saturation, hemoglobin and plasma erythropoietin. All participants in this study signed informed consent, and 5 ml peripheral blood was drawn from each participant.

Selection of SNPs and methods of genotyping

Twenty-eight SNPs from two genes were chosen for analysis in this study. A total of 14 SNPs in EPHA2 and 14 SNPs in AGT. Minor allele frequencies of all SNPs >5% in the Asian population HapMap database. Because the genetic basis of HAPC has not been compared between the Han ethnic groups and Tibetans, we selected candidate and SNPs based on the hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) pathway, which were associated with high altitude adaptation in the Chinese Han and Tibetan populations. Colorado et al. [12] reported EPHA2 receptor mediates increased vascular permeability in lung injury due to viral infection and hypoxia. Furthermore, Huynh-Do et al. [10] reported the effect of local renal hypoxia on EPHA2 and EPO regulation, they found EPHA2 increases modulates EPO expression after renal hypoxia injury. Gao et al. [9] identified the rs699 polymorphism in the AGT gene was associated with HAPC susceptibility in Tibetans. Sequenom Mass ARRAY Assay Design 3.0 software was used to design multiplexed SNP Mass EXTEND assay, and SNP genotyping was performed utilizing the Sequenom Mass ARRAY RS1000 recommended by the manufacturer [13].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, United States). Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was calculated using SHEs is online software for patients and controls. Data are reported the proportion [odds ratio (OR)] and 95% confidence interval (CI), evaluated by three genetic models (dominant, recessive and additive) using unconditional logistic regression analysis adjusted for age and gender, and these three genetic models were performed using PLINK software and SNPStats (a web based program available at http://bioinfo.iconcologia.net/snpstats/start.htm) to assess the association of SNPs with the risk of HAPC. Multiple stepwise regression analysis was performed to assess which individual characteristic affected hemoglobin in HAPC patients, the level of entry was set at 0.05. All p values presented were calculated based on a two-sided test and statistical significance was established when p < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31260252; 31460286; 31660307), the Natural Science Foundation of Xizang (Tibet) Autonomous Region (No. Z2014A09G2-3), the Innovation Support Program for Young Teachers of Tibet Autonomous Region (No. QCZ2016-27; QCZ2016-29), the Science and Technology Department Project of Tibet Autonomous Region (No. 2016ZR-MQ-06; 2015ZR-13-19). We would like to express our appreciation to those who collected samples in the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, and we thank everyone who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Lijun Liu and Yao Zhang, participated in the design of study and helped to draft the manuscript. Zhiying Zhang, Yiduo Zhao, and Xiaowei Fan, designed the primers and carried out the genetic study. Lifeng Ma and Yuan Zhang, collected the blood samples and participated in the design of study. Haijing He, data collection and analysis. Longli Kang, conceived in the design of study.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.León-Velarde F, Maggiorini M, Reeves JT, Aldashev A, Asmus I, Bernardi L, Ge RL, Hackett P, Kobayashi T, Moore LG. Consensus statement on chronic and subacute high altitude diseases. High Alt Med Biol. 2005;6:147–57. doi: 10.1089/ham.2005.6.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Windsor JS, Rodway GW. Heights and haematology: the story of haemoglobin at altitude. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:148–51. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.049734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer BF. Physiology and pathophysiology with ascent to altitude. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:69–77. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181d3cdbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simonson TS, Yang Y, Huff CD, Yun H, Qin G, Witherspoon DJ, Bai Z, Lorenzo FR, Xing J, Jorde LB. Genetic evidence for high-altitude adaptation in Tibet. Science. 2010;329:72–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1189406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan W, Ga Q, Li R, Bai ZZ, Wuren T, Wang J, Yang YZ, Li YH, Ge RL. Sleep disturbances in long-term immigrants with Chronic Mountain Sickness: a comparison with healthy immigrants at high altitude. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;206:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong C, Di Rienzo A. Adaptations to local environments in modern human populations. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;29:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beall CM, Cavalleri GL, Deng L, Elston RC, Gao Y, Knight J, Li C, Li JC, Liang Y, McCormack M, Montgomery HE, Pan H, Robbins PA, et al. Natural selection on EPAS1 (HIF2alpha) associated with low hemoglobin concentration in Tibetan highlanders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11459–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002443107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buroker NE, Ning XH, Zhou ZN, Li K, Cen WJ, Wu XF, Zhu WZ, Scott CR, Chen SH. EPAS1 and EGLN1 associations with high altitude sickness in Han and Tibetan Chinese at the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2012;49:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Jiang C, Luo Y, Liu F, Gao Y. Interaction of CARD14, SENP1 and VEGFA polymorphisms on susceptibility to high altitude polycythemia in the Han Chinese population at the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2016;57:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez S, Rudloff S, Koenig KF, Karthik S, Hoogewijs D, Huynh-Do U. Bidirectional signalling between EphA2 and ephrinA1 increases tubular cell attachment, laminin secretion and modulates erythropoietin expression after renal hypoxic injury. Pflugers Arch. 2016;468:1433–48. doi: 10.1007/s00424-016-1838-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buroker NE, Ning XH, Zhou ZN, Li K, Cen WJ, Wu XF, Ge M, Fan LP, Zhu WZ, Portman MA. Genetic associations with mountain sickness in Han and Tibetan residents at the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1466–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cercone MA, Schroeder W, Schomberg S, Carpenter TC. EphA2 receptor mediates increased vascular permeability in lung injury due to viral infection and hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L856–63. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00118.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabriel S, Ziaugra L, Tabbaa D. SNP genotyping using the Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX platform. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2009;12:2.12.1–6. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0212s60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang C, Chen J, Liu F, Luo Y, Xu G, Shen HY, Gao Y, Gao W. Chronic mountain sickness in Chinese Han males who migrated to the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau: application and evaluation of diagnostic criteria for chronic mountain sickness. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:701. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li K, Gesang L, Dan Z, Gusang L. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis reveals the protection against hypoxia-induced oxidative injury in the intestine of Tibetans via the inhibition of GRB2/EGFR/PTPN11 pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:6967396. doi: 10.1155/2016/6967396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu TY. Chronic mountain sickness on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Chin Med J (Eng1) 2005;18:161–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldwin C, Chen ZW, Bedirian A, Yokota N, Nasr SH, Rabb H, Lemay S. Upregulation of EphA2 during in vivo and in vitro renal ischemia-reperfusion injury: role of Src kinases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F960–71. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00020.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimke H, Sparks MA, Thomson BR, Frische S, Coffman TM, Quaggin SE. Tubulovascular cross-talk by vascular endothelial growth factor a maintains peritubular microvasculature in kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1027–38. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014010060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberger C, Griethe W, Gruber G, Wiesener M, Frei U, Bachmann S, Eckardt KU. Cellular responses to hypoxia after renal segmental infarction. Kidney Int. 2003;64:874–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klopsch C, Furlani D, Gäbel R, Li W, Pittermann E, Ugurlucan M, Kundt G, Zingler C, Titze U, Wang W. Intracardiac injection of erythropoietin induces stem cell recruitment and improves cardiac functions in a rat myocardial infarction model. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:664–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00546.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brunner S, Winogradow J, Huber BC, Zaruba MM, Fischer R, David R, Assmann G, Herbach N, Wanke R, Mueller-Hoecker J. Erythropoietin administration after myocardial infarction in mice attenuates ischemic cardiomyopathy associated with enhanced homing of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells via the CXCR-4/SDF-1 axis. FASEB J. 2009;23:351–61. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-109462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Jiang C, Luo Y, Liu F, Gao Y. Interaction of CARD14, SENP1 and VEGFA polymorphisms on susceptibility to high altitude polycythemia in the Han Chinese population at the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2016;57:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koehle MS, Wang P, Guenette JA, Rupert JL. No association between variants in the ACE and angiotensin II receptor 1 genes and acute mountain sickness in Nepalese pilgrims to the Janai Purnima Festival at 4380 m. High Alt Med Biol. 2006;7:281–9. doi: 10.1089/ham.2006.7.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalson NS, Thompson J, Davies AJ, Stokes S, Earl MD, Whitehead A, Tyrrell-Marsh I, Frost H, Montgomery H. The effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme genotype on acute mountain sickness and summit success in trekkers attempting the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro (5,895 m) Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;105:373–9. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0913-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai CT, Lai LP, Lin JL, Chiang FT, Hwang JJ, Ritchie MD, Moore JH, Hsu KL, Tseng CD, Liau CS. Renin-angiotensin system gene polymorphisms and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;109:1640–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124487.36586.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aksu S, Beyazit Y, Haznedaroglu I, Kekilli M, Canpinar H, Misirlioğlu M, Uner A, Tuncer S, Sayinalp N, Büyükasik Y. Enhanced expression of the local haematopoietic bone marrow renin-angiotensin system in polycythemia rubra vera. J Int Med Res. 2005;33:661–7. doi: 10.1177/147323000503300608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vrsalovic MM, Pejsa V, Veic TS, Kolonic SO, Ajdukovic R, Haris V, Jaksic O, Kusec R. Bone marrow renin-angiotensin system expression in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia depends on JAK2 mutational status. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:1430–2. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.9.4568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]