Abstract

BACKGROUND

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia among women at high risk for primary occurrence or recurrence of disease. Recommendations for the use of aspirin for preeclampsia prevention were issued by the USPSTF in September 2014.

OBJECTIVES

To evaluate the incidence of recurrent preeclampsia in our cohort before and after the USPSTF recommendation for aspirin for preeclampsia prevention.

STUDY DESIGN

This is a retrospective cohort study designed to evaluate rates of recurrent preeclampsia among women with a history of preeclampsia. We utilized a two hospital, single academic institution database from August 2011 through June 2016. We excluded multiple gestations and included only the first delivery for women with multiple deliveries during the study period. The cohort of women with a history of preeclampsia were divided into two groups, “before” and “after” the release of the USPSTF 2014 recommendations. Potential confounders were accounted for in multivariate analyses, and relative risk and adjusted relative risk were calculated.

RESULTS

17,256 deliveries occurred during the study period. A total of 417 women had a documented history of prior preeclampsia; 284 women “before” and 133 women “after” the USPSTF recommendation. Comparing the before and after groups, the proportion of Hispanic women in the after group was lower and the method of payment differed between the groups (P <.0001). The prevalence of type 1 diabetes was increased in the after period, but overall rates of pregestational diabetes were similar (6.3% before versus 5.3% after; P >.05). Risk factors for recurrent preeclampsia included maternal age >35 years (RR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.34–2.48), Medicaid insurance (RR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.15–3.78), type 1 diabetes (RR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.37–3.33), and chronic hypertension (RR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.44–2.66). The risk of recurrent preeclampsia was decreased by 30% in the after group (adjusted relative risk (aRR), 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52- 0.95).

CONCLUSION

Rates of recurrent preeclampsia among women with a history of preeclampsia decreased by 30% after release of the USPSTF recommendation for aspirin for preeclampsia prevention. Future prospective studies should include direct measures of aspirin compliance, gestational age at initiation, and explore the influence of race and ethnicity on the efficacy of this primary prevention.

Keywords: aspirin, preeclampsia, prevention

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia is a common obstetrical complication that affects 5 to 10% of pregnancies and is a major cause of multi- organ dysfunction and maternal morbidity resulting from generalized endothelial dysfunction.1 Preeclampsia often results in fetal growth restriction and medically-indicated preterm delivery with associated neonatal morbidity of prematurity (e.g. respiratory issues, neonatal intensive care unit admission).

Estimates of recurrent preeclampsia risk vary with most reports citing a risk of 15–25%,2–4 although 65% of women with preeclampsia onset in the second trimester experienced recurrent preeclampsia in one study.5 The variation in reported recurrence risk is likely explained by differences in patient populations including differences in known risk factors for recurrent preeclampsia (severity of preeclampsia, gestational age at onset).6 In one prospective study from Sweden in 2009, among gravidae affected by preeclampsia in their first pregnancy, the risk of recurrent preeclampsia was 14.7% in the second pregnancy and 31.9% in the third pregnancy.2 In this study, the authors advocated for two distinct preeclamptic cohorts, one of which experience severe, recurrent, and generally earlier onset and are affected by chronic maternal, genetic, and environmental factors.

The underlying etiology and pathophysiology of both primary and recurrent preeclampsia is incompletely understood but is thought to involve dysfunctional cytotrophoblastic invasion, placental ischemia, and release of inflammatory and endothelial mediators.7, 8 At a mechanistic level, via inhibition of the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, aspirin decreases the ratio of thromboxane to prostacyclins resulting in net increased uteroplacental blood flow.9, 10 Thus, aspirin retains the biological plausibility to reduce the occurrence of preeclampsia by relatively well-defined pharmacologic mechanisms.

In September 2014, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published their recommendations regarding the use of low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention for pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia, including women with a prior history of both early and late gestation preeclampsia.11 Their recommendations were based on a systematic review and meta-analysis suggesting that aspirin was associated with absolute risk reductions of 2% to 5% for preeclampsia (relative risk (RR), 0.76, 95% CI; 0.62–0.95), 1% to 5% for intrauterine growth restriction (RR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.65–0.99), and 2% to 4% for preterm birth (RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76–0.98).12 Since publication of these recommendations, multiple meta-analyses have suggested an observable and significant impact of initiation of first or early mid-trimester initiation of low-dose aspirin therapy for the prevention of both primary and recurrent preeclampsia among at-risk gravidae.13, 14 However, evidence of a population-based impact of the USPSTF recommendation has not yet been undertaken. The objective of this study was to evaluate the clinical impact of the USPSTF recommendation for low- dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention on rates of recurrent preeclampsia.

METHODS

Study design, subjects, and database characteristics

This research study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (H-26364; H-33382; most recent approval May 16, 2016). This is a retrospective nested cohort study designed to evaluate rates of preeclampsia among women with a history of preeclampsia before and after the late 2014 USPSTF recommendation aspirin for preeclampsia prevention recommendations. Women with a history of preeclampsia were the cohort of interest due to the highest risk for recurrence and ability to standardize over time. In addition, it is possible that baseline co-morbid occurrences rendering risk for primary preeclampsia (i.e., chronic hypertension, type 1 and type 2 diabetes, morbid obesity) increased in the reference population. For these reasons, we chose to specifically examine the occurrence of recurrent preeclampsia rather than the occurrence of the disease overall.

We utilized a two hospital, single academic institution database of deliveries from August 2011 through June 2016. Based in Houston, Texas, PeriBank is a comprehensive, institutional database and biobank focusing on detailed clinical data and accompanying specimens collected at delivery and curated at Baylor College of Medicine. A detailed description of PeriBank has been published previously.15 At the time of admission, gravidae were enrolled by trained PeriBank research personnel after written informed consent was obtained. Up to 4,900 variables of clinical data were sought from the electronic medical record, prenatal records, and by in-person interview. The quality of the data was ascertained by regular verification of a subset of the inserted clinical data and by at least one board-certified maternal-fetal medicine physician scientist (K.M.A.) as previously published.15 Clinical data that were extracted for this study comprise the patient history (including prior and familial occurrence of preeclampsia, smoking status, nicotine and substance use, familial obstetrical history, and prenatal care clinics and providers), socioeconomic status (education, income, immigration status) and residential and workplace data (each trimester of pregnancy residence and work place five-digit zip code). Not all 4,900 potential PeriBank variables were employed in this analysis.

Inclusion criteria

Subjects included in the current study were enrolled in our PeriBank database between August 2011 and June 2016 (N=17,256 deliveries). The index pregnancy is the most recent pregnancy in the database for each subject. All women with a history of preeclampsia in a prior pregnancy were identified. Women with multiple gestations were excluded, and only the first pregnancy during the time period for each woman was included. Women were assigned to the before and after groups based on the date of delivery for the index (most recent) pregnancy.

Outcome measures and data analysis

The primary outcome in this analysis was the incidence of recurrent preeclampsia in the index pregnancy. All clinical and demographic data for pregnancies enrolled into our study were obtained from PeriBank. Preeclampsia was defined by American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) diagnostic criteria. Of note, the diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia changed in 2013 before the guideline was implemented.16, 17 A history of preeclampsia is documented in our database as is the gestational age at prior delivery; however, the severity of preeclampsia is not specified. The use of magnesium sulfate and preterm delivery were utilized as surrogates for preeclampsia with severe features. Preterm delivery was defined as delivery prior to 37 weeks of gestation. Groups of interest were compared by chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, and Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-normal continuous variables. Linear regression was performed for the trend in recurrent preeclampsia in the before and after groups.

In an effort to control for potential confounders, multivariate modeling was undertaken. Generalized linear models (GLMM, Proc GENMOD in SAS version 9.4) were used for estimation of Relative Risk (RR), adjusted RR and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for binomial outcome variables (preeclampsia in this pregnancy [primary outcome], preterm birth, and magnesium sulfate for use in labor [secondary outcomes]). Generalized linear mixed models (Proc GLIMMIX in SAS version 9.4) was used for estimation of least square means (LSM) for non-normally distributed continuous outcome variables and comparison between study groups. Possible confounders were assessed initially and controlled for by including them in the regression models. Adjustments were made for maternal age, Hispanic ethnicity, method of payment, gestational age at first visit, type 2 diabetes, chronic hypertension, and gestational age at diagnosis of preeclampsia in last pregnancy. P <.05 was considered statistically significant. The number needed to treat (NNT) was calculated as the inverse of absolute risk reduction (absolute risk reduction = control event rate (before) less the experimental event rate (after).

RESULTS

During the study period, 17,256 deliveries were captured in our PeriBank database. A total of 417 pregnancies were identified as high risk for preeclampsia based on a history of preeclampsia; 284 pregnancies “before” and 133 pregnancies “after” the USPSTF recommendation for low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention (Table 1). Comparing before and after groups, the proportion of Hispanic gravidae in the after group was lower and the method of payment differed between the groups (p <.0001). The prevalence of type 1 diabetes was increased in the after period, but overall rates of pregestational diabetes were similar (6.3% before versus 5.3% after, p >.05). There were no significant differences in maternal age (p = .585), African American race (p= .252), gestational age at first visit (p= .055), BMI (p= .969), smoking status (p = .445), chronic hypertension (p= .178), gestational age of diagnosis for prior preeclampsia (p = .209), gestational age at delivery this pregnancy (p = .917), or preterm delivery this pregnancy (p= .826).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics comparing pregnancies complicated by previous preeclampsia before and after the USPSTF recommendation for low-dose aspirin.

| Characteristic | BEFORE USPSTF guideline for aspirin N=284 |

AFTER USPSTF guideline for aspirin N=133 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Maternal age, mean (SD) | 30.04 (6.05) | 30.40 (6.44) | 0.585 |

|

| |||

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic, N (%) | 217 (76.4%) | 66 (49.6%) | <0.0001* |

| African American, N (%) | 39 (13.7%) | 24 (18.1%) | 0.252 |

|

| |||

| Method of payment, N (%) | <0.0001* | ||

| Medicaid | 104 (36.6%) | 52 (39.1%) | 0.626 |

| Chip | 116 (40.9%) | 27 (20.3%) | <0.0001* |

| Private | 26 (9.2%) | 50 (37.6%) | <0.0001* |

| Other | 38 (13.4%) | 4 (3.0%) | 0.007* |

|

| |||

| Gestational age at first visit, median (IQR) | 13 (9–19) | 11.5 (9–15) | 0.055 |

|

| |||

| BMI, median (IQR) | 33.6 (30.0–37.9) | 33.70 (29.4–39.1) | 0.969 |

|

| |||

| Smokers, N (%) | 0.445 | ||

| Current | 7 (2.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Never/Ever | 277 (97.5%) | 132 (99.3%) | |

|

| |||

| Pregestational diabetes, N (%) | |||

| Type 1 | 2 (0.7%) | 5 (3.8%) | 0.036* |

| Type 2 | 16 (5.6%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0.064 |

|

| |||

| Chronic hypertension, N (%) | 58 (20.4%) | 35 (26.3%) | 0.178 |

|

| |||

| Gestational age prior preeclampsia, median (IQR) | 37 (34–40) | 36 (35–38) | 0.209 |

|

| |||

| Gestational age at delivery this pregnancy, median (IQR) | 38 (37–39) | 38 (37–39) | 0.917 |

|

| |||

| Preterm delivery this pregnancy, N (%) | 69 (24.3%) | 31 (23.3%) | 0.826 |

significant based on p<0.05

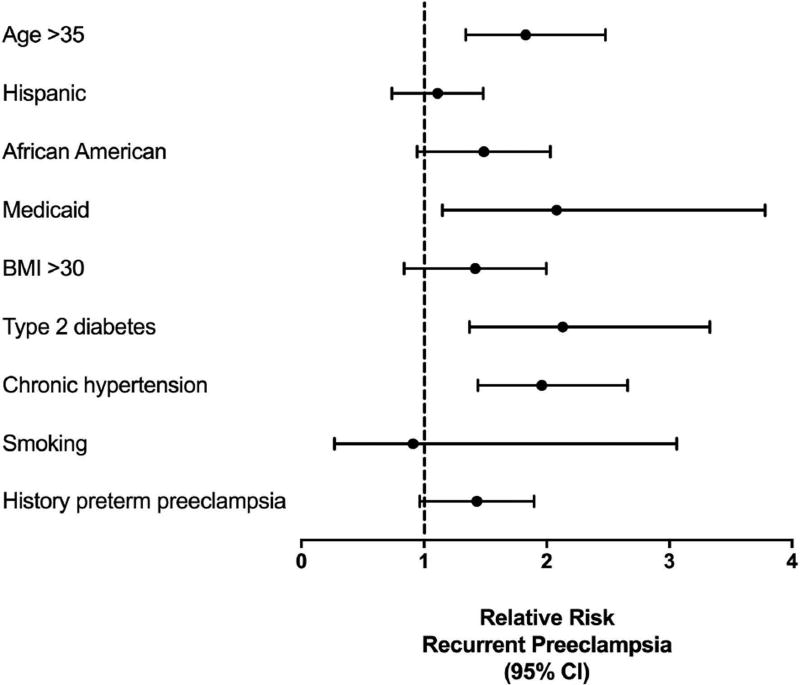

Maternal age >35 years (RR, 1.83; 95% CI 1.34–2.48), Medicaid payment (RR, 2.08; 95% CI 1.15–3.78), type 2 diabetes (RR, 2.13; 95% CI 1.37–3.33), and chronic hypertension (RR, 1.96; 95% CI 1.44–2.66) were risk factors for recurrent preeclampsia (Table 2; Figure 1). Hispanic ethnicity (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.76–1.50), African American race (RR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.98–2.06), BMI >30 (RR, 1.34; 95% CI, 0.88–2.03), smoking (RR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.27–3.06), and prior preterm preeclampsia (RR, 1.38; 95% CI, 0.99–1.92) were not significantly associated with recurrent preeclampsia. As expected, gravidae who experience recurrent preeclampsia were more likely to be delivered preterm (RR, 3.28; 95% CI, 2.46–4.39).

Table 2.

Comparison of pregnancies complicated by recurrent preeclampsia versus no recurrent preeclampsia.

| Characteristic | Recurrent preeclampsia N=114 |

No recurrent preeclampsia N=303 |

Relative Risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Maternal age >35 years, N (%) | 42 (36.8%) | 59 (19.5%) | 1.83 (1.34–2.48)* |

|

| |||

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic, N (%) | 79 (69.3%) | 204 (67.3%) | 1.07 (0.76–1.50) |

| African American, N (%) | 23 (20.2%) | 40 (13.2%) | 1.42 (0.98–2.06) |

|

| |||

| Method of payment, N (%) | |||

| Medicaid | 47 (41.2%) | 109 (36.0%) | 2.08 (1.15–3.78)* |

| CHIP | 39 (34.2%) | 104 (34.3%) | 1.88 (1.03–3.46)* |

| Private | 11 (9.7%) | 65 (21.5%) | 1.0 |

| Other | 17 (14.9%) | 25 (8.3%) | 2.80 (1.45–5.40)* |

|

| |||

| BMI >30, N (%) | 85/106 (80.2%) | 209/285 (73.3%) | 1.34 (0.88–2.03) |

|

| |||

| Pregestational diabetes, N (%) | |||

| Type 1 | 0 | 7 (2.3%) | -- |

| Type 2 | 10 (8.8%) | 8 (2.6%) | 2.13 (1.37–3.33)* |

|

| |||

| Chronic hypertension, N (%) | 41 (36.0%) | 52 (17.2%) | 1.96 (1.44–2.66)* |

|

| |||

| Smokers, N (%) | 0.91 (0.27–3.06) | ||

| Current | 2 (1.8%) | 6 (2.0%) | |

| Ever/Never | 112 (98.3%) | 297 (98.0%) | |

|

| |||

| Preterm (<37 weeks) prior preeclampsia, N (%) | 57/106 (53.8%) | 122/286 (42.7%) | 1.38 (0.99–1.92) |

|

| |||

| Preterm delivery (<37 weeks) this pregnancy, N (%) | 58 (50.9%) | 42 (13.9%) | 3.28 (2.46–4.39)* |

significant based on relative risk 95% confidence interval that does not contain 1.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of risk factors for recurrent preeclampsia among the cohort overall, with relative risk and 95% confidence intervals. BMI=body mass index

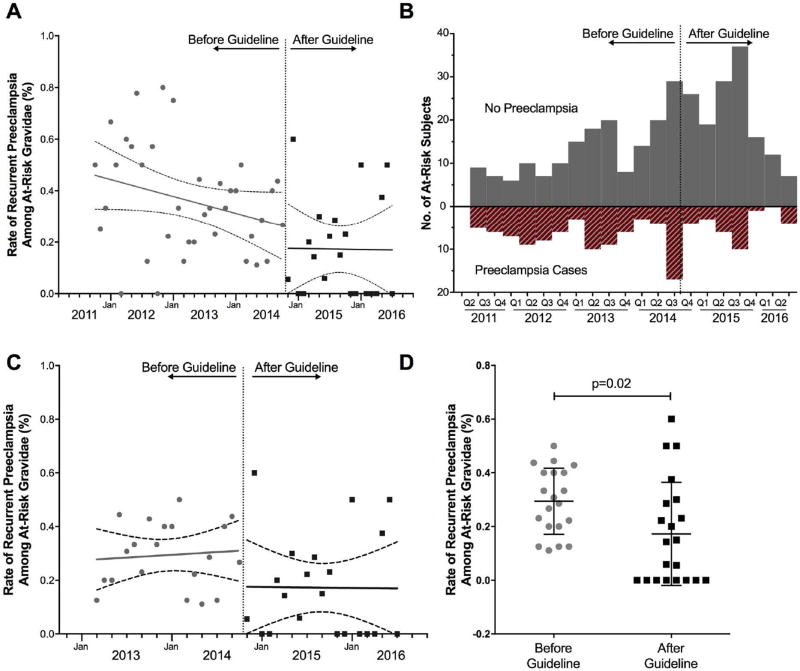

Recurrent preeclampsia occurred in fewer women after the USPSTF recommendation based on adjusted analyses (32.4% before versus 16.5% after; aRR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52–0.95) (Table 3, Figure 2A and 2B). There was a downward trend in the incidence of recurrent preeclampsia prior to the intervention, but the slope was not significant in the before or after period (P 0.086 and P = 0.965, respectively). When the data was limited to two years before and two years after the recommendation, there was not a decreasing tend in preeclampsia rates, and the difference between before and after groups remained significant (P = 0.02, Figure 2C and 2D). There was no significant difference in the use of magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis during labor (25.0% before versus 18.3% after; aRR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.46–1.10) or preterm delivery (24.3% before versus 23.3% after; aRR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.68–1.43). The NNT to prevent one case of preeclampsia for all women with a history of preeclampsia in our cohort was 6.

Table 3.

Outcomes among women with a history of preeclampsia before and after the USPSTF recommendation for low-dose aspirin.

| Outcome | BEFORE USPSTF guideline for aspirin N=284 |

AFTER USPSTF guideline for aspirin N=133 |

Relative Risk (95% CI) |

Adjusted Relative Risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preeclampsia this pregnancy, N (%) | 92 (32.4%) | 22 (16.5%) | 0.51 (0.34–0.77)* | 0.70 (0.52–0.95)* |

| Magnesium sulfate during labor, N (%) | 69 (25.0%) | 24 (18.3%) | 0.73 (0.48–1.11) | 0.71 (0.46–1.10) |

| Preterm delivery, N (%) | 69 (24.3%) | 31 (23.3%) | 0.96 (0.66–1.39) | 0.99 (0.68–1.43) |

significant based on relative risk 95% confidence interval that does not contain 1.

Adjusted for maternal age, Hispanic ethnicity, method of payment, gestational age at first visit, type 2 diabetes, chronic hypertension, and gestational age previous preeclampsia

Figure 2.

Pregnancies affected by recurrent preeclampsia (and those not affected) over time, before and after the USPSTF recommendation for aspirin for preeclampsia prevention. “At-risk” was defined by gravidae documented as having had preeclampsia in a prior pregnancy. A. Trends in rates of recurrent preeclampsia 2011–2016. B. Bar graph of recurrent preeclampsia by quarter 2011–2016. C. Trend in rates of recurrent preeclampsia 2013–2016 (2 years before and after the USPSTF recommendation). D. Scatter plot of rate of recurrent preeclampsia 2013–2016 (2 years before and after the USPSTF recommendation).

COMMENT

Rates of recurrent preeclampsia among women with a history of preeclampsia decreased by 30% after the USPSTF recommendation for low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention. The decreased incidence of recurrent preeclampsia was not accounted for by differences in known accompanying risk factors for preeclampsia in our multivariable analysis. The quarterly representation of data in Figure 2B similarly shows no evidence of seasonal variation in the incidence of recurrent preeclampsia, suggesting that temporal seasonal variation alone could not account for our findings.18, 19 Paradoxically, we did observe a higher proportion of at-risk women who did not experience recurrent preeclampsia which argues against change in regional referral patterns or birthrates affecting our results.

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses have been conducted to test the hypothesis that aspirin can reduce the incidence of preeclampsia.20–23 Two large trials from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Unit (MFMU) Network and the Collaborative Low-Dose Aspirin Study in Pregnancy (CLASP) provided most of the data for subsequent meta-analyses.24, 25 The MFMU conducted a multicenter, randomized placebo controlled trial of low-dose aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia in 2,503 women.24 The study population was women deemed to be at high risk of preeclampsia based on pregestational diabetes requiring insulin, chronic hypertension, multifetal gestations, or a history of preeclampsia in prior pregnancies. They found that aspirin did not lower the incidence of preeclampsia in any of these groups (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.77–1.06). CLASP was a multinational trial including 9,364 women who were enrolled to prevent or treat preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction.25 They found a 12% nonsignificant decrease in proteinuric preeclampsia in the aspirin group (RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.75–1.03).

A subsequent meta-analysis published in 2003 that included 14 trials of over 12,000 women showed that aspirin reduced the incidence of preeclampsia and perinatal death (OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76–0.96 and OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.64- 0.96, respectively).26 In 2007, the PARIS Collaborative Group published a meta-analysis with individual patient level data from 31 trials including 32,217 women. Women who received aspirin had 10% reduction in the relative risk of preeclampsia (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.84–0.97), delivery before 34 weeks (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83–0.98), and pregnancy with a serious adverse outcome (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.85–0.96).27 More recent studies have examined the effect of prophylactic anticoagulation in addition to aspirin on placenta-mediated complications with conflicting results.28–30 The evidence regarding the dose-dependent efficacy and impact of gestational age at initiation are similarly poorly defined.31, 32

One novel finding of our study was related to estimates of at-risk recurrence when our cohort was stratified by its inherent racial and ethnic variation. Interestingly, the relative proportion of Hispanic women experiencing recurrent preeclampsia in the post-USPSTF recommendation strata was lower, while the proportion of African American gravidae and those with chronic hypertension was higher. Since our cohort is largely Hispanic, we cannot distinguish whether these observations are due to relative over or underpowering. However, the data trend is of potential interest and, although difficult to ascertain from this study alone, these findings potentially suggest that there may be racial and ethnic variation in responsiveness to low-dose aspirin prophylaxis for recurrence of preeclampsia. The results of our study differ substantially from previous trials in that our effect size was much larger (overall effect sizes from larger trials were small with an approximately 10% reduction).24, 25 However, our results are in agreement with the meta-analysis that prompted the USPSTF recommendation (RR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62–0.95).12 We speculate that in our patient population, which is largely Hispanic, aspirin may be particularly effective. Future pharmacogenomics studies and analyses may benefit from study design aimed to directly assess whether aspirin has varying degrees of effectiveness for preventing preeclampsia among different races and ethnicities; this would be in alliance with current precision medicine initiatives.

Our study has both limitations and strengths. Limitations of our study include the retrospective nature and inability to control for all potential confounders. Another limitation includes the lack of data on which women received aspirin, individual subject compliance with aspirin, and gestational age at initiation of therapy. As an observational study, we are unable to assert a causal association; our findings suggest a temporal association with the USPSTF aspirin guideline for prevention of preeclampsia with robust adjustments for potential confounders which did not explain our findings. Additionally, by design, our cohort included only women with a history of preeclampsia and did not include women without a history of preeclampsia with other risk factors for preeclampsia including those for whom aspirin is recommended (e.g., multifetal gestation, chronic hypertension, pregestational diabetes, renal disease, and autoimmune disease).11 However, a history of preeclampsia is the predictor for preeclampsia with reported 7-fold relative risk33, and the overall primary rate of preeclampsia is virtually unchanged across populations and over generations. Thus, the strata within which we chose to examine recurrence is a strength of our approach and limits ascertainment bias inherent to large population-based studies. Similarly, the large number of deliveries and manually abstracted data, rather than utilization of diagnosis codes, strengthen the validity our results over other population-based analyses.

Finally, the greatest strength of our study was its ability to estimate the effect of release of a USPSTF recommendation for the use of low-dose aspirin at a population-wide level, inclusive of inherent imperfect use and application. We observed a 30% risk reduction across the population which could not be explained by any factor other than the temporal introduction of such guidelines. The clinical use of aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia is estimated to decrease the rate of recurrent preeclampsia in women at the highest risk of recurrence in our practice, and our NNT estimate across the entirety of the population over time was 6. Aspirin is a low cost intervention with widespread availability and proven ability to reduce morbidity and healthcare costs.34, 35 The future for the study of aspirin for preeclampsia prediction is bright including planned studies to incorporate early screening tests for preeclampsia to determine eligibility for aspirin use.36, 37 Future studies should include women with indications for aspirin other than a history of preeclampsia and further explore the influence of race and ethnicity on the preventive efficacy of low-dose aspirin.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: The effort for this work was funded by the NIH (grant number R01NR014792 to K.M.A) and the March of Dimes Prematurity Research Initiative (K.M.A.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Paper presentation information: This work was presented as abstract 60 at the 37th Annual Pregnancy Meeting, January 23–28, 2017, Las Vegas, Nevada.

References

- 1.Committee Opinion No. 638: First-Trimester Risk Assessment for Early-Onset Preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e25–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez-Diaz S, Toh S, Cnattingius S. Risk of pre-eclampsia in first and subsequent pregnancies: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b2255. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surapaneni T, Bada VP, Nirmalan CP. Risk for Recurrence of Pre-eclampsia in the Subsequent Pregnancy. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2889–91. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/7681.3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Rijn BB, Hoeks LB, Bots ML, Franx A, Bruinse HW. Outcomes of subsequent pregnancy after first pregnancy with early-onset preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:723–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sibai BM, Mercer B, Sarinoglu C. Severe preeclampsia in the second trimester: recurrence risk and long-term prognosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1408–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90379-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boghossian NS, Yeung E, Mendola P, et al. Risk factors differ between recurrent and incident preeclampsia: a hospital-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:871–7e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spradley FT, Palei AC, Granger JP. Immune Mechanisms Linking Obesity and Preeclampsia. Biomolecules. 2015;5:3142–76. doi: 10.3390/biom5043142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spradley FT, Palei AC, Granger JP. Increased risk for the development of preeclampsia in obese pregnancies: weighing in on the mechanisms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;309:R1326–43. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00178.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2005;365:785–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17987-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke RJ, Mayo G, Price P, FitzGerald GA. Suppression of thromboxane A2 but not of systemic prostacyclin by controlled-release aspirin. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1137–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeFevre ML. Force USPST. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:819–26. doi: 10.7326/M14-1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O'Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:695–703. doi: 10.7326/M13-2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberge S, Sibai B, McCaw-Binns A, Bujold E. Low-Dose Aspirin in Early Gestation for Prevention of Preeclampsia and Small-for-Gestational-Age Neonates: Meta-analysis of Large Randomized Trials. Am J Perinatol. 2016;33:781–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1572495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meher S, Duley L, Hunter K, Askie L. Antiplatelet therapy before or after 16 weeks' gestation for preventing preeclampsia: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antony KM, Hemarajata P, Chen J, et al. Generation and validation of a universal perinatal database and biospecimen repository: PeriBank. J Perinatol. 2016;36:921–9. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of O, Gynecologists, Task Force on Hypertension in P. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1122–31. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulletins--Obstetrics ACoP. ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Number 33, January 2002. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:159–67. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips JK, Bernstein IM, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ. Seasonal variation in preeclampsia based on timing of conception. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1015–20. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000143306.88438.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tam WH, Sahota DS, Lau TK, Li CY, Fung TY. Seasonal variation in pre-eclamptic rate and its association with the ambient temperature and humidity in early pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2008;66:22–6. doi: 10.1159/000114252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bujold E, Roberge S, Lacasse Y, et al. Prevention of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction with aspirin started in early pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:402–14. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e9322a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberge S, Giguere Y, Villa P, et al. Early administration of low-dose aspirin for the prevention of severe and mild preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29:551–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villa PM, Kajantie E, Raikkonen K, et al. Aspirin in the prevention of pre-eclampsia in high-risk women: a randomised placebo-controlled PREDO Trial and a meta-analysis of randomised trials. BJOG. 2013;120:64–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu TT, Zhou F, Deng CY, Huang GQ, Li JK, Wang XD. Low-Dose Aspirin for Preventing Preeclampsia and Its Complications: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2015;17:567–73. doi: 10.1111/jch.12541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:701–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803123381101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CLASP: a randomised trial of low-dose aspirin for the prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia among 9364 pregnant women. CLASP (Collaborative Low-dose Aspirin Study in Pregnancy) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1994;343:619–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coomarasamy A, Honest H, Papaioannou S, Gee H, Khan KS. Aspirin for prevention of preeclampsia in women with historical risk factors: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1319–32. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Askie LM, Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Stewart LA, Group PC. Antiplatelet agents for prevention of pre-eclampsia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2007;369:1791–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60712-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haddad B, Winer N, Chitrit Y, et al. Enoxaparin and Aspirin Compared With Aspirin Alone to Prevent Placenta-Mediated Pregnancy Complications: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1053–63. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberge S, Demers S, Nicolaides KH, Bureau M, Cote S, Bujold E. Prevention of pre-eclampsia by low-molecular-weight heparin in addition to aspirin: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:548–53. doi: 10.1002/uog.15789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katsi V, Kanellopoulou T, Makris T, Nihoyannopoulos P, Nomikou E, Tousoulis D. Aspirin vs Heparin for the Prevention of Preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2016;18:57. doi: 10.1007/s11906-016-0664-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberge S, Nicolaides K, Demers S, Hyett J, Chaillet N, Bujold E. The role of aspirin dose on the prevention of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore GS, Allshouse AA, Post AL, Galan HL, Heyborne KD. Early initiation of low-dose aspirin for reduction in preeclampsia risk in high-risk women: a secondary analysis of the MFMU High-Risk Aspirin Study. J Perinatol. 2015;35:328–31. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duckitt K, Harrington D. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ. 2005;330:565. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38380.674340.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Werner EF, Hauspurg AK, Rouse DJ. A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Low-Dose Aspirin Prophylaxis for the Prevention of Preeclampsia in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:1242–50. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartsch E, Park AL, Kingdom JC, Ray JG. Risk threshold for starting low dose aspirin in pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia: an opportunity at a low cost. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mone F, Mulcahy C, McParland P, et al. An open-label randomized-controlled trial of low dose aspirin with an early screening test for pre-eclampsia and growth restriction (TEST): Trial protocol. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;49:143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Gorman N, Wright D, Rolnik DL, Nicolaides KH, Poon LC. Study protocol for the randomised controlled trial: combined multimarker screening and randomised patient treatment with ASpirin for evidence-based PREeclampsia prevention (ASPRE) BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011801. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]