Abstract

Background

Aseptic meningitis represents a common diagnostic and management dilemma to clinicians.

Objectives

To compare the clinical epidemiology, diagnostic evaluations, management, and outcomes between adults and children with aseptic meningitis.

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective study from January 2005 through September 2010 at 9 Memorial Hermann Hospitals in Houston, TX. Patients age ≥ 2 months who presented with community-acquired aseptic meningitis with a CSF white blood cell count >5 cells/mm3 and a negative Gram stain and cultures were enrolled. Patients with a positive cryptococcal antigen, positive blood cultures, intracranial masses, brain abscesses, or encephalitis were excluded.

Results

A total of 509 patients were included; 404 were adults and 105 were children. Adults were most likely to be female, Caucasian, immunosuppressed, have meningeal symptoms (headache, nausea, stiff neck, photophobia) and have a higher CSF protein (P<0.05). In contrast, children were more likely to have respiratory symptoms, fever, and leukocytosis (P<0.05). In 410 (81%) patients, the etiologies remained unknown. Adults were more likely to be tested for and to have Herpes simplex virus and West Nile virus while children were more likely to be tested for and to have Enterovirus (P<0.001). The majority of patients were admitted (96.5%) with children receiving antibiotic therapy more frequently (P<0.001) and adults receiving more antiviral therapy (P=0.001). A total of 384 patients (75%) underwent head CT scans and 125 (25%) MRI scans; all were normal except for meningeal enhancement. All patients had a good clinical outcome at discharge.

Discussion

Aseptic meningitis in adults and children represent a management challenge as etiologies remained unknown for the majority of patients due to underutilization of currently available diagnostic techniques.

Keywords: aseptic meningitis, children, adults, diagnosis, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Aseptic meningitis is defined as an acute community-acquired syndrome with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis in the absence of a positive Gram stain and culture, without a parameningeal focus or a systemic illness, and with a good clinical outcome [1]. This case definition has remained relatively unchanged since its initial description in 1925 by Wallgren. The clinical syndrome has since been further characterized and understood to include multiple types of infectious and non-infectious etiologies, although up to 71% of those cases remain with uncertain etiology, especially when PCR testing is not completed. [2]. The most common etiologies of aseptic meningitis in the United States (US) are viruses such as Enterovirus, Herpes simplex type 2, and West Nile virus. Varicella zoster virus and Cytomegalovirus have also been described as causes of aseptic meningitis [2]. Several prior studies have sought to develop clinical models to try to differentiate this diagnosis from other urgent treatable conditions such as bacterial meningitis and encephalitis [3–4]. To standardize the case definition, a recent international working group defined aseptic meningitis as patients with meningitis symptoms, a CSF white cell count of >5 cells/mm3, and a negative CSF Gram stain [5]. The diagnostic certainty of this syndrome was further stratified into three levels: Level 1 if the patient had negative CSF cultures without previous antibiotic exposure, Level 2 with negative CSF cultures with previous antibiotic therapy and Level 3 with concomitant encephalitis.

Despite such tools, evaluation of this clinical syndrome in the present day clinical setting remains variable representing a diagnostic and management dilemma to clinicians. As such, the purpose of this study was to characterize and compare the baseline characteristics, management strategies, etiologies of adult and pediatric patients with aseptic meningitis and to uncover the frequency and yield of the use of available diagnostic techniques and cranial imaging in this syndrome.

METHODS

Study Design & Case Definitions

A retrospective observational cohort study was completed spanning from January 2005 through September 2010. Cases were defined in a similar method to those cited by Tapiainen et al using only Level 1 and 2 diagnostic certainties [5]. Patients above 2 months of age presenting to the emergency department from the community with acute symptoms of meningitis, CSF white cell count of >5 cells/mm3, negative Gram stain and culture, and no identified parameningeal focus of infection were included by reviewing all cases with an ICD9 discharge code of meningitis. The cohort was composed of patients presenting to nine Memorial Hermann hospitals, all within the greater Houston metropolitan area. Patients aged 18 years or older were considered adults for the purposes of this study. Baseline patient characteristics at time of presentation to the emergency department, use of microbiologic and imaging modalities, and Glasgow outcome scores [6] at time of discharge were evaluated. The study was approved by the University of Texas Medical School at Houston Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and by the Memorial Hermann Hospital Research Review Committee.

Statistical Assessment

Comparisons of baseline and clinical characteristics were made between pediatric and adult patients using the chi square test for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables with significance attributable at P<0.05. All statistical analysis was completed using SPSS for Mac version 21 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

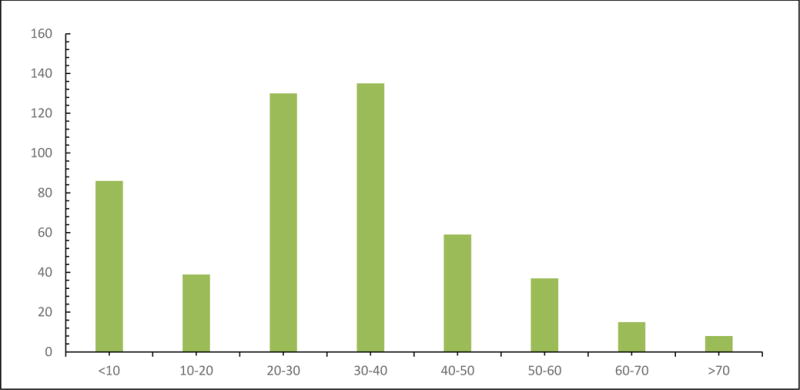

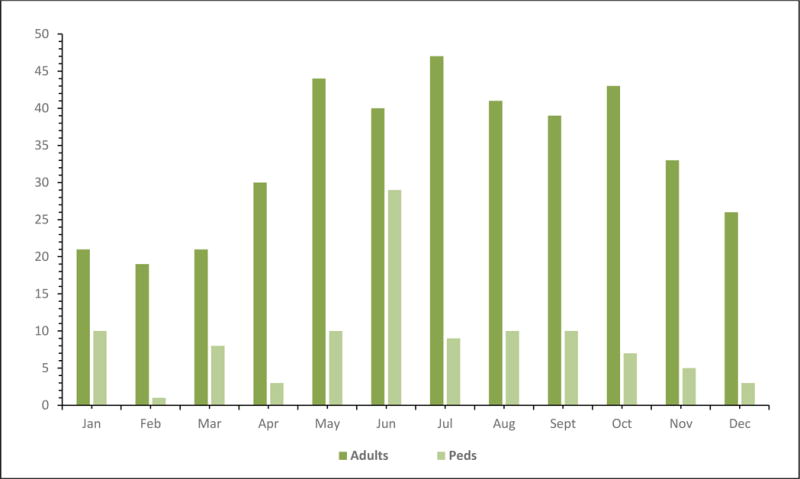

RESULTS

We identified a total of 907 adults and children with meningitis above the age of 2 months. We excluded 398 patients for the following reasons: positive Gram stain for bacteria or yeast (n=113), nosocomial meningitis (n=101), encephalitis presentation (n=86), and positive CSF or blood culture (n=84), and incomplete medical records (n=14). A total of 509 patients met the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 shows the age distribution for all the cases in decades with the majority of patients being between 20 and 40 years old. Figure 2 shows the distribution by month of presentation with the most common time between May and October. As shown in Table 1, adults composed the majority of patients at 404 (79%) while 105 (21%) patients were children; the median age in the adults was 34 years (18–89) and in the pediatrics it was 4.9 years (2 months-17 years of age). The majority of patients were 20–40 years old (see Figure 1). Male gender was more common in pediatric patients (59% vs 42%, P=0.002). There were also significant differences in the ethnicity with adults and children having more Caucasian and Hispanics, respectively (p<0.001). More adults were immunocompromised than children (22.5% vs 4.7%, P <0.001). Previous antibiotic therapy was used more commonly in pediatrics than adults (37.1% vs. 7.2%, P <0.001). The majority of the patients with aseptic meningitis presented between the months of May and October (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Age distribution in years of 509 adults and children with Aseptic Meningitis.

Figure 2.

Distribution by month of year of 509 Adults and Children with Aseptic Meningitis.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics, clinical presentations, and laboratory results in 509 Adults and Children with Aseptic Meningitis.

| Variable | Adults (n=404) |

Children (n=105) |

Total (n=509) |

P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age, years (range) | 34 (18–89) | 4.9 (0.17–17) | 30 (0.17–89) | <0.001 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 171(42.3) | 62 (59) | 233 (45.8) | 0.002 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| White | 198 (49) | 21 (20) | 219 (43) | |

| African American | 101 (25) | 26 (24.7) | 127 (24.9) | |

| Hispanic | 91 (22.5) | 55 (52.4) | 146 (28.7) | |

| Asian | 14 (3.4) | 3 (2.8) | 17 (1.9) | |

| Immunosuppressedb, n (%) | 91 (22.5) | 5 (4.7) | 96 (18.9) | <0.001 |

| Previous antibiotic therapy, IV or POc n (%) | 27 (6.6) | 39 (37.1) | 66 (12.9) | <0.001 |

| Presenting Symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Headache | 399 (98.8) | 63 (60) | 462 (90.8%) | <0.001 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 302 (74.8) | 67 (63.8) | 369 (72.5) | 0.02 |

| Stiff neck | 207 (51.2) | 25 (23.8) | 232 (45.6%) | <0.001 |

| Photophobia | 187 (46.3) | 28 (26.7) | 215 (42.2%) | <0.001 |

| Malaise/Weakness | 142 (35.1) | 7 (6.7) | 149 (29.3) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory symptoms | 46 (11.4) | 33 (31.4) | 79 (15.5) | <0.001 |

| Presenting Signs, n (%) | ||||

| Temperature > 100.4 F | 93 (23) | 91 (86.7) | 184 (36.1) | <0.001 |

| Nuchal Rigidity | 125 (30.9) | 13 (12.4) | 138 (27.1) | <0.001 |

| Normal neurological examd | 404 (100) | 105 (100) | 509 (100) | 1 |

| Vesicular or petechial rash | 6 (1.5) | 5 (4.7) | 11 (2.1) | 0.004 |

| Laboratory results, n (%) | ||||

| Median CSF leukocyte count (cells/μl), range | 162.5 (6–10,100) | 109 (4.9–49,000) | 150 (4.9–49,000) | 0.066 |

| Median CSF mononuclear count (cells/μl), range | 74 (12–100) | 78 (8–98) | 76 (8–100) | 0.456 |

| Median CSF polymorphonuclear count (cells/μl), range | 21 (0–88) | 14 (3–92) | 17 (0–92) | 0.321 |

| Median CSF protein (mg/dL), range | 70 (18–706) | 44 (15–300) | 66 (15–706) | <0.001 |

| Median CSF glucose (mg/dL), range | 57 (23–366) | 58.5 (30–98) | 57 (23–366) | 0.951 |

| Median serum leukocyte count (103 X cells/μl), | 8.4 (0.9–42) | 12.4 (3.1–46.5) | 9.0 (0.9–46.5) | <0.001 |

P value comparing adult and pediatric cohorts

Human immunodeficiency virus, chronic steroid recipients, status post recent (< 1month) chemotherapy, or solid or bone marrow transplant recipients.

intravenous or oral antibiotic therapy

Glasgow Coma scale =15 and no focal neurological deficits or seizures

There were several differences between adults and children in the baseline clinical and laboratory presentations (see Table 1). Adults were more likely than children to complaint of headache, nausea or vomiting, stiff neck, malaise, photophobia, and have nuchal rigidity present on exam (p<0.05). Fever, concurrent respiratory illness, and rash were more commonly seen in the pediatric population (p<0.05). On initial CSF evaluation, adult patients had a trend to have a higher CSF WBC count (p=0.066) and also had higher CSF protein (p<0.001) than the pediatric group. Children also had higher median CSF neutrophilic pleocytosis than adults (P<0.001). Children had higher serum leukocyte counts than adults (p <0.001).

Diagnostic testing differed between adults and children (see Table 2). Adults were more commonly tested for HIV (30% vs. 5.7%, P <0.001) with only 10 (8.1%) of adults testing positive for HIV. Virological studies such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Herpes simplex virus (HSV), Enterovirus and Varicella Zoster virus (VZV) and serologies for West Nile virus (WNV) were done in the minority of patients. Out of the 509 patients in the cohort, only 175 (34.4%) had PCR for HSV sent, 165 (32.4%) for WNV studies, 138 (27.1%) for enterovirus PCR, 6 (1.2%) for VZV PCR, and 1 patient each for Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Mycoplasma pneumoniae PCR. Furthermore, 182 (35.8 %) of the patients had no viral studies sent at all. When done, the yield of an enterovirus PCR was 35.5% and for HSV PCR it was 20.6%. The overall yield of a West Nile serology was 4.8% (8 out 96 (8.3%) cases in the West Nile season between June and October and 0 out of 69 (0%) between November and May) and all positive cases were adults. Adults were more likely to have testing for HSV (p<0.001) and West Nile virus (p=0.001) while pediatric patients were more likely to have testing completed for enterovirus (p=0.036). Children were more likely to have at least one viral study (CSF PCR or arboviral serology) sent compared to adults (75.2% vs 61.3%, P=0.008) and also were less likely to have an unknown infectious etiology (60.9% vs 85.6%, P<0.001). Overall only 94 (18.5%) patients out of the total study had an infectious etiology identified [Enterovirus (n=49). Herpes simplex virus (n=36), West Nile virus (n=8), Varicella Zoster virus (n=1)].

TABLE 2.

Diagnostic Testing in 509 Adults and Children with Aseptic Meningitis*

| Laboratory test | Adults (n=404) |

Children (n=105) |

Total (n=509) |

P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV serology done | 123 (30.0) | 6 (5.7) | 129 (25.3) | <0.001 |

| HIV serology positive | 10 (8.1) | 0 (0) | 10 (7.7) | 0.001 |

| Herpes simplex virus PCRb done | 158 (39.1) | 17 (16.2) | 175 (34.4) | <0.001 |

| Herpes simplex virus PCR positive | 36 (22.8) | 0 (0) | 36 (20.6) | 0.016 |

| West Nile virus serologies done | 150 (37.1) | 15 (14.3) | 165 (32.4) | 0.001 |

| West Nile virus positive | 8 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 8 (4.8) | N/A |

| Enterovirus PCR done | 60 (14.9) | 78 (74.3) | 138 (27.1) | <0.001 |

| Enterovirus PCR positive | 9 (15) | 40 (51.3) | 49 (35.5) | <0.001 |

| Varicella Zoster virus PCR done | 4 (1) | 2 (1.9) | 6 (1.2) | 0.36 |

| Varicella Zoster virus PCR positive | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 0.667 |

| Other PCR donec | 0 (0) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (0.3) | 0.206 |

| Other PCR positive | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| At least one viral study done | 248 (61.3) | 79 (75.2) | 327 (64.2) | 0.008 |

| Unknown etiologyd | 350 (86.6) | 65 (61.9) | 405 (81.5) | <0.001 |

All values in parenthesis represent percentages of total or percentages percentage of positive test results of total tests completed.

P value comparing adult and children cohorts;

polymerase chain reaction;

Cytomegalovirus (1), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (1);

Adults: Known etiologies: HSV (36); Enterovirus (9); West Nile virus (8); Cytomegalovirus (1), M. pneumoniae (1); Children: Enterovirus (40).

As shown in Table 3, the majority of patients (96.5%) were admitted to the hospital for a median duration of 4 days (range 1–34 days). Empiric antibiotic therapy was given to the majority of patients (77.4%) with children receiving them more frequently than adults (92.3% vs 73.5%, p <0.001). Empiric antiviral therapy with acyclovir was administered in 17.1% of the patients and was given more frequently in the adult population (19.8% vs 6.6%, p= 0.001). A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the head was performed in 384 (75%) patients and 125 (25%) patients had a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. Adults were more likely than children to have a CT scans and MRI of the brain done (p<0.001). Of the CT scans completed, none showed significant abnormalities and only 11 (8.8%) of the MRI scans with contrast showed some meningeal enhancement. All patients in the retrospective cohort had a good outcome based on Glasgow outcome scale.

TABLE 3.

Management Decisions in 509 Adults and Children with Aseptic Meningitis.

| Adults (n=404) |

Children (n=105) |

Total (n=509) |

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management Decisions, n (%) | ||||

| Admission to the Hospital | 386 (95.6) | 105 (100) | 491 (96.5) | 0.769 |

| Median duration of hospitalization, days (range) | 4 (1–34) | 3 (1–33) | 4 (1–34) | 0.210 |

| Empiric Antibiotic therapy | 297 (73.5) | 97 (92.3) | 394 (77.4) | <0.001 |

| Empiric Acyclovir therapy | 80 (19.8) | 7 (6.6) | 87 (17.1) | 0.001 |

| Head CTb scan done | 349 (86.3) | 35 (33.3) | 384 (75.4) | <0.001 |

| Normal | 100 (0) | 100 (0) | 100 (0) | N/A |

| MRIb of Brain done | 115 (28.5) | 10 (9.5) | 125 (24.5) | <0.001 |

| Meningeal enhancement | 9 (7.8) | 2 (20) | 11(8.8) | N/A |

| Adverse clinical outcomec | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

P value comparing adult and pediatric cohorts

CT: Computerized Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Glasgow outcome scale from 1–4.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest cohort studies of aseptic meningitis to date and the first one to compare adults and children. In our study, children were less likely to present with meningeal complaints (e.g., headache, stiff neck, nausea, photophobia) than adults. This is consistent with other studies were children more often present with a nonspecific febrile illness without meningismus [2]. Children were also most likely to present with fever, respiratory symptoms, and leukocytosis and to be exposed to previous antibiotic therapy before lumbar puncture. Even though approximately one third of children received antibiotic therapy, the majority were not treated for partially treated bacterial meningitis as the median length of stay and antibiotic therapy was 3 days. The etiology was not revealed in 81.5% in our study, while other series which performed PCR for the most common viral etiologies reported less proportion of unknown etiologies (50–70%) [7–9]. This low yield could in part be explained by underutilization of PCR for the most common viruses and for arboviral serologies in real-life practice [10]. We think that tools to diagnose viral meningitis may be underutilized due to the generally benign course of illness with physicians primarily concerned with ruling out bacterial meningitis. We believe testing for viruses in aseptic meningitis is important as it may help clinicians avoid hospitalization, reduce length of stay in those admitted and reduce the use of empirical antimicrobial therapy. Even though when they were completed, they had a high yield in identifying a significant number of enterovirus and HSV cases in pediatric and adult cases, respectively. Identifying HSV as the most common etiology in adults was unusual despite the low proportion of patients tested. These viruses have also been found to be the most common etiologies in other series as well [6–9]. Several reports from Europe [7,8] and Asia [9] have now revealed that VZV it is the second most common leading cause of ASM even in the absent of skin lesions (Zoster sine herpete). In our study, only 1.2% of patients underwent a CSF VZV PCR making this an underdiagnosed etiology. Furthermore, it is also unclear the impact that VZV vaccination in childhood and Zoster vaccine in adults might have on the impact on the incidence of VZV meningitis.

In addition, checking WNV serology should be done during the endemic season (June through October) to enhance the diagnostic yield. [9] Additionally, only 25% of all patients with aseptic meningitis had an HIV serology done. Although we do not have a HIV PCR data from the serum or CSF, it is worth to mention that acute HIV infection could present as ASM and it has been overlooked from most of the major ASM series. A retrospective study revealed 3.4% of the remaining CSF tested positive for high HIV viral load in CSF. [10] Furthermore, we do not have PCR data for bacterial pathogens and therefore under-detection of culture-negative bacterial meningitis would be another limitation of this study.

The underutilization of PCR likely keeps infectious etiologies from being uncovered in a large majority of cases. When completed, they helped identify a significant number of enterovirus and HSV cases. This is concerning as it suggests that epidemiologic studies on infectious etiologies of aseptic meningitis are likely confounded by underuse of this diagnostic tool. In other studies, enterovirus and herpes viruses have also been cited as common etiologic agents. [10,11, 12,13] Furthermore, choice of PCR testing varies between adult and pediatric patients and these differences may well be due to paucity of sound epidemiologic studies. With the introduction of rapid multiplex PCR machines, this will likely change in the future.

Cranial imaging is commonly used in ASM and it is not helpful as all the scans were normal and did not alter management. A recent study [15] documents the lack of adherence of clinicians to the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines and confirms the lack of utility of obtaining cranial imaging in the absence of specific indications. Additionally, the majority of patients were admitted to the hospital and received empiric antibiotic therapy until CSF cultures were finalized as negative. Our study also confirms recent findings that viral meningitis can present with neutrophilic pleocytosis that is more common in children with enterovirus infection [16]. Identifying viral causes with a rapid PCR test could potentially avoid or decrease the length of stay in the majority of cases [17]. Overall, we found that the original definition of aseptic meningitis still holds true as does the assertion that patients afflicted with this disease process have generally good outcomes, aside from possible neuropsychological sequelae, despite the diagnostic and treatment choices done by clinicians.

Our study had several advantages from previous work. First, this is the largest aseptic meningitis study done to date in the US since the 1960’s. Second, this is the only study comparing adults and children with aseptic meningitis. Lastly, this study is also the largest study documenting the underutilization of currently available diagnostic techniques in this syndrome.

Despite the strengths, there are several limitations to this study. First, approximately one third of children had previous antibiotic therapy and could have had partially treated bacterial meningitis (Level 2 aseptic meningitis criteria). This would be unlikely as all the patients with or without antibiotic exposure had a good clinical outcome and the median length of intravenous antibiotic therapy was 3 days. Second, we did not account for non-infectious etiologies for aseptic meningitis such as adverse effects of medications, chemotherapy, or vaccines. Third, we did not analyze if there was an increase in the use of PCR during the study period and it is possible that the use of molecular tests has now increased. Finally, as our cohort was limited to patients admitted to a several hospitals in Houston, Texas the diagnostic practices and findings in aseptic meningitis have to be generalized in other populations.

CONCLUSIONS

Aseptic meningitis represents a diagnostic challenge as the majority of patients have unknown etiologies. Available diagnostic studies such as West Nile virus serologies and PCR for Enterovirus and Herpes simplex viruses are being underutilized and the majority are hospitalized and treated empirically with intravenous antibiotic therapy. Aseptic meningitis continues to be associated with a benign clinical outcome.

Highlights.

Aseptic Meningitis have unknown etiologies in 81% of patients

Currently available virological tools are underutilized.

The majority of patients undergo unnecessary cranial imaging and antibiotic therapy.

All patients had a good clinical outcome.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr and Mrs Starr for their continuous support of our studies.

FUNDING

National Center for Research Resources (NIH-1 K23 RR018929-01A2) (Dr. Rodrigo Hasbun) and Grant A Starr Foundation (Dr. Susan Wootton). www.grantastarr.org

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

No competing interests for BS, LS, EA, SH, QK. RH is a consultant to bioMérieux and is part of the speaker’s bureau for the Medicine’s company, Merck, Pfizer and Biofire diagnostics.

Ethical Approval:

The study was approved by the University of Texas Medical School at Houston Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and by the Memorial Hermann Hospital Research Review Committee.

References

- 1.Wallgreen A. Une nouvelle maladie infectieuse du system nerveux central? Acta Padiatr. 1925;4:158–82. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasbun R. The Acute Aseptic Meningitis Syndrome. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2000;2:345–351. doi: 10.1007/s11908-000-0014-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spanos A, Harrell F, Durack D. Differential diagnosis of acute meningitis, an analysis of the predictive value of initial observations. JAMA. 1989;262(19):2700–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasbun R, Bijlsma M, Brouwer MC, Khoury N, Hadi CM, et al. Risk score for identifying adults with CSF pleocytosis and negative CSF Gram stain at low risk for an urgent treatable cause. J Infect. 2013 Apr 22;:S0163–4453. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tapiainen T, et al. Aseptic meningitis: case definition and guidelines for collection, analysis and prevention of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2007;25(31):5793–802. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khoury N, Hossain M, Wootton S, Salazar L, Hasbun R. Meningitis with a negative Gram stain in Adults: Risk Classification for an adverse clinical outcome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Dec;87(12):1181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frantzidou F, Kamaria F, Dumaidi K, Skoura L, Antoniadis A, Papa A. Aseptic meningitis and encephalitis because of herpesviruses and enteroviruses in an immunocompetent adult population. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:995–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Ory F, Avellón A, Echevarría JE, Sánchez-Seco MP, Trallero G, Cabrerizo M, et al. Viral infections of the central nervous system in Spain: a prospective study. J Med Virol. 2013;85:554–562. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han S, Choi H, Kim J, Park K, Youn Y, Shin H. Etiology of aseptic meningitis and clinical characteristics in immune-competent adults. J Med Virol. 2016;88(1):175–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanichanan J, Salazar L, Wootton SH, Aguilera E, Garcia MN, Murray KO, et al. Use of Testing for West Nile Virus and Other Arboviruses. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22 doi: 10.3201/eid2209.152050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanson KE, Reckleff J, Hicks L, Castellano C, Hicks CB. Unsuspected HIV Infection in Patients Presenting with Acute Meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:433–434. doi: 10.1086/589931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang A, Machicado J, Khoury N, Wootton S, Salazar L, Hasbun R. Community-Acquired Meningitis in Older Adults: Clinical Features, Etiology, and Prognostic Factors. J of Amer Geri Soc. 2014 Nov;62(11):2064–70. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kupila L, Vuorinen T, Vainionpaa R, Hukkanen V, Marttila RJ, Kotilainen P. Etiology of aseptic meningitis and encephalitis in an adult population. Neurology. 2006;66:75–80. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191407.81333.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarrin I, Sellier P, Lopes A, Morgand M, Makovec T, Delcey V, et al. Etiologies and management of aseptic meningitis in patients admitted to an internal medicine department. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(2):e2372. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salazar L, Hasbun R. Cranial imaging before lumbar puncture in adults with community-acquired meningitis: clinical utility and adherence to the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Mar 21; doi: 10.1093/cid/cix240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaijakul S, Salazar L, Wootton SH, Aguilera E, Hasbun R. The clinical significance of neutrophilic pleocytosis in cerebrospinal fluid in patients with viral central nervous system infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;59:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wootton SH, Aguilera E, Salazar L, Hemmert AC, Hasbun R. Enhancing pathogen identification in patients with meningitis and a negative Gram stain using the Biofire Film Array Meningitis/Encephalitis panel. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2016 Apr 21;15(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s12941-016-0137-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]