Abstract

Background

Despite decades of attempts to link infectious agents to preterm birth, an exact causative microbe or community of microbes remains elusive. Non-culture 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing suggests important racial differences and pregnancy specific changes in the vaginal microbial communities. A recent study examining the association of the vaginal microbiome and preterm birth documented important findings but was performed in a predominantly White cohort. Given the important racial differences in bacterial communities within the vagina as well as persistent racial disparities in preterm birth it is important to examine cohorts with varied demographic compositions.

Objective

The objective of this study was to characterize vaginal microbial community characteristics in a large, predominantly African-American, longitudinal cohort of pregnant women and test whether particular vaginal microbial community characteristics are associated with the risk for subsequent preterm birth.

Study Design

This is a nested case-control study within a prospective cohort study of women with singleton pregnancies, not on supplemental progesterone, and without cervical cerclage in situ. Serial mid-vaginal swabs were obtained by speculum exam at their routine prenatal visits. Sequencing of the V1V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene was performed on the Roche 454 platform. Alpha diversity community characteristics including richness, Shannon diversity, and evenness as well as beta diversity metrics including Bray Curtis Dissimilarity and specific taxon abundance were compared longitudinally in women who delivered preterm to those who delivered at term.

Results

77 subjects contributed 149 vaginal swabs longitudinally across pregnancy. Participants were predominantly African-American (69%) and had a preterm birth rate of 31%. In subjects with subsequent term delivery the vaginal microbiome demonstrated stable community richness and Shannon diversity whereas subjects with subsequent preterm delivery had significantly decreased vaginal richness, diversity, and evenness during pregnancy (P<0.01). This change occurred between the first and second trimesters. Within subject comparisons across pregnancy showed that preterm birth is associated with increased vaginal microbiome instability compared to term birth. No distinct taxa were associated with preterm birth.

Conclusions

In a predominantly African-American population, a significant decrease of vaginal microbial community richness and diversity is associated with preterm birth. The timing of this suppression appears early in pregnancy, between the first and second trimesters, suggesting that early gestation may be an ecologically important time for events that ordain subsequent term and preterm birth outcomes.

Keywords: Pregnancy, preterm birth, vaginal microbiome

Introduction

Preterm birth, delivery at less than 37 weeks of gestation, complicates 12% of pregnancies in the United States 1 and has been appropriately termed “the principal unsolved problem in perinatal medicine”2. Decades of research have attempted to link maternal infections and inflammation to preterm birth, but an exact causative microbe or microbial community remains elusive in the preponderance of cases. For example, the association between maternal genitourinary infections in pregnancy and the risk for preterm birth has been repeatedly demonstrated 3-10, yet antibiotics have not been shown to prevent preterm birth11-14, and in some cases treatment is associated with a paradoxically increased risk of preterm delivery 15. These data likely reflect our incomplete understanding of normal and abnormal vaginal microbial communities during pregnancy.

The advent of non-culture characterization of microbial communities using 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) gene sequencing offers a much broader understanding of vaginal microbial communities. Seminal work by Ravel et al. demonstrated that vaginal communities of asymptomatic, non-pregnant, reproductive age women clustered into five distinct “community-state types” which differed both by dominant Lactobacillus species as well as overall community composition 16. A much higher proportion of African-American and Hispanic women harbored a non-Lactobacillus dominant community, suggesting that in some women a non-Lactobacillus based vaginal community may be a normal variant. This finding challenges long-held beliefs about the definition of normal and abnormal vaginal microbiota. Other groups have documented that the vaginal microbiome during pregnancy differs from that of the non-pregnant vaginal microbiome 17, 18 suggesting that the physiology of pregnancy itself alters the microbial composition of this niche.

In view of the pregnancy-dependent composition of the vaginal microbiome, the considerable racial differences in the microbial composition of the vagina and in rates of preterm birth, and conflicting findings of recent studies 19-21, it is important to further test the hypothesis that differences in vaginal microbial community structure during pregnancy are associated with preterm birth. A recent study examined vaginal microbial composition and the risk for preterm birth but had very few African-Americans and few preterm births 21. Here, we characterize vaginal microbial community characteristics over time in a large predominantly African-American cohort of pregnant women and test whether particular community characteristics are associated with the risk for subsequent preterm birth.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Clinical Data

We performed a nested case-control study within a prospective cohort of pregnant women receiving prenatal care at a single tertiary care institution from 2012-2015. The Washington University Human Research Protection Office approved this study (HRPO 201202015). Inclusion criteria were singleton gestation, willingness to undergo speculum exam for vaginal sampling, and provision of informed consent. Exclusion criteria were planned or in situ cervical cerclage and planned or current vaginal or intramuscular progesterone therapy. Participants were followed throughout their prenatal course with serial vaginal swabs obtained at routine prenatal visits. Subject demographic data, medical history, and clinical obstetric outcome data were collected by trained research staff as the patient progressed through prenatal care. Race was self-reported. Gestational age was determined by best obstetric estimate using last menstrual period and earliest ultrasound data available. Microbial characteristics were compared between cases, defined as preterm birth <37 weeks of gestation) and term birth controls (delivery ≥ 37 weeks of gestation).

Sample collection and DNA extraction

Speculum examinations were performed by the treating obstetrician to obtain mid-vaginal collections. After speculum insertion into the vaginal canal a sterile dual-tipped rayon swab (Starplex Scientific, Ontario Canada) was applied to both lateral walls of the vaginal canal 3-5 times per sidewall. The swab was then placed into the sterile collection tube, immediately stored at -20°C until transportation to the laboratory, and then frozen at -80°C until DNA extraction.

DNA was extracted according to the protocol used by the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) 22. Genomic DNA was isolated using the manufacturer protocol from the MO BIO PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Carlsbad CA). All extracted samples were stored in solution at -80°C until sequencing. DNA concentration was quantified by Qubit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham MA).

16S rRNA gene Sequencing and sequence data processing

Pyrosequencing of V1V3 and V3V5 variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene and data processing were performed according to standardized protocols developed by the HMP Human Microbiome Project 23, 24 on the Roche 454 GS FLX.

(V1V3 Primers:

27F-5′ CCTATCCCCTGTGTGCCTTGGCAGTCTCAG_AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG

534R5′ CCATCTCATCCCTGCGTGTCTCCGACTCAG_INDEX_ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG.

V3V5 Primers:

357F-5′ CCTATCCCCTGTGTGCCTTGGCAGTCTCAG_ CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG

926R-5′CCATCTCATCCCTGCGTGTCTCCGACTCAG_INDEX_CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGT)

The primary analysis including species level classification of Lactobacillus was performed using the V1V3 rRNA region. Because of the known limitation of this region for classification of Gardnerella25, the V3V5 region was used to examine Gardnerella patterns between groups.

Samples were binned by allowing one mismatch in the barcodes. Reads were filtered out if the average quality scores were less than 35 and/or read length less than 200 base pairs. Chimeric sequences were removed using Chimera-Slayer. Three samples with < 1000 reads were excluded from the analysis. Reads passing quality control were then classified from phylum to genus level using the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) Naive Bayesian Classifier (version 2.5, training set 9). Taxa assigned with less than 0.5 confidence were reassigned to the next higher taxonomic level in which the classification threshold was greater than 0.5. To classify the Lactobacillus reads into species, we built a local database containing all the 16S rRNA genes of Lactobacillus species from the NCBI database and blasted the processed V1V3 reads to the Lactobacillus species database. If a read had the same bit score for more than one Lactobacillus species, it was designated as “unclassified Lactobacillus.”

Statistical Analyses

Each sample was subsampled to the lowest number of read counts among samples in the dataset and rarefied to 2000 reads. The abundance of a taxon in a sample was indicated as the relative abundance, which was calculated by dividing the number of reads for a taxon by the total read counts of the sample. Alpha diversity indices including richness, Shannon diversity and Pielou's evenness index were were calculated as described 26. To test the change of alpha diversity across pregnancy in preterm and full term birth groups, we applied linear mixed regression with log-transformed alpha diversity index (richness, Shannon diversity, and Pielou evenness) as the response variable, three trimesters, and delivery status (term or preterm) as fixed variables, and subjects as random effects. We also included an interaction term of trimester and term versus preterm groups in the model. We used Wilcoxon-rank sum testing to measure the significance of differences in richness, Shannon diversity, and Pielou's evenness in each trimester for women with subsequent preterm birth compared to women whose pregnancies went to term.

To examine beta-diversity between term and preterm samples we performed non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plots and used Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) to determine statistical differences between term and preterm samples at each trimester. Additionally we examined microbiome community stability using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity in samples from the same subject between trimesters 1 and 2 and trimesters 2 and 3. Stability differences between subjects with term and preterm birth were performed using a t-test. Taxon-specific analysis was performed using taxa with representation > 1% for the whole cohort and heatmaps were generated clustering term and preterm birth outcomes by trimester to examine community composition in Lactobacillus dominant and Lactobacillus poor communities. Differences in specific individual taxa between term and preterm groups in each trimester was tested by Wilcoxon Rank Sum.

All analyses were performed in R (www.r-project.org) and Stata 12.0 (College Station, TX) statistical programs. Two-tailed P values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant unless otherwise stated.

Results

Cohort and Specimen Characteristics

Seventy-seven subjects contributed 149 vaginal swabs for analysis including 27, 61, and 61 swabs from the first, second, and third trimesters, respectively. Most (69%) participants were African-Americans. Of these 77 women, 24 (31%) subsequently experienced preterm birth and 9 (37.5%) of these preterm births were attributed to spontaneous preterm labor or preterm rupture of membranes. The mean gestational age of delivery in the preterm group was 33 weeks versus 38 weeks in the term birth group (Table 1a). Women who delivered at term did not differ significantly from those who delivered preterm with respect to race, body mass index, tobacco use, diabetes, parity, or history of prior preterm birth.

Table 1a. Characteristics of subjects with term birth compared to those with preterm birth.

| Characteristics | Total Cohort | Term Delivery | Preterm Delivery | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of subjects | 77 | 53 (68.8%) | 24 (31.2%) | --- |

| Total number of swabs | 149 | 101 (68.4%) | 48 (31.5%) | --- |

| Trimester 1 (weeks 6-13) | 27 (9.4%) | 18 (9.6%) | 9 (9.1%) | 0.6 |

| Trimester 2(weeks 14-26) | 61 (19.0%) | 41 (19.5%) | 20 (17.9%) | 0.5 |

| Trimester 3 (weeks 27-40) | 61 (30.5%) | 43 (30.2%) | 18 (31.1%) | 0.1 |

| Subjects contributed 1 swab (n) | 23 | 14 | 9 | --- |

| Subjects contributed 2 swabs (n) | 36 | 27 | 9 | --- |

| Subjects contributed 3 swabs (n) | 18 | 11 | 7 | --- |

| Race | ||||

| African-American Race – Yes | 53 (68.8%) | 37 (69.8%) | 16 (66.6%) | 0.8 |

| African-American Race - No | 24 (31.2%) | 16 (30.1%) | 8 (33.3%) | 0.5 |

| Mean Gestational Age of Delivery | 36.8 ± 2.6 | 38.2 ± 1.1 | 33.8 ± 2.4 | <0.01 |

| (weeks ± SD) | ||||

| Parity (mean ± SD) | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 1.1 ±1.9 | 0.5 |

| Prior preterm births | 16 (20.8%) | 9 (16.9%) | 17 (29.1%) | 0.2 |

| Preterm Birth < 37 weeks | 24 (31.1%) | --- | --- | --- |

| Spontaneous PTD < 37 weeks | 9 (37.5%) | --- | --- | --- |

| Preterm Rupture of Membranes | 6 (25.0%) | --- | --- | --- |

| BMI (Mean ± SD) | 32 ± 9 | 33 ± 9 | 30 ± 10 | 0.3 |

| Tobacco Use | 19 (24.7%) | 13 (24.5%) | 6 (25.0%) | 0.9 |

| Pre-gestational Diabetes | 27 (35.1%) | 32.1% | 41.7% | 0.4 |

| Gestational Diabetes | 10 (13.0%) | 15.1% | 8.3% | 0.4 |

n(%), unless otherwise listed

The 149 swab specimens produced a total of 1,158,489 processed V1V3 reads, averaging 7775 reads/sample. Table 1b demonstrates gestational age of delivery, gestational ages of swab collection, and indication for delivery for all subjects who delivered preterm. Graphical representation of longitudinal sample collection for all subjects in the cohort relative to delivery timing is available in Supplemental Material (Supplement Figure 1). Characteristics of women who were enrolled in the first trimester were similar to those who enrolled later in pregnancy, except that women with pre-gestational diabetes were more likely to be enrolled in the first trimester.

Table 1b. Delivery data and swab distribution for preterm deliveries.

| Individual | Indication for Preterm Delivery | Gestational age of delivery (weeks) | Swab 1 Gestational age (weeks) | Swab 2 Gestational age (weeks) | Swab 3 Gestational age (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PTL | 34 | 17 | ||

| 2 | PROM | 36 | 8 | 15 | 30 |

| 3 | PTL | 32 | 18 | 27 | |

| 4 | PROM | 36 | 7 | 22 | 31 |

| 5 | PTL | 34 | 9 | 30 | |

| 6 | PROM | 35 | 19 | ||

| 7 | PTL | 36 | 8 | 17 | 32 |

| 8 | PTL | 36 | 26 | 35 | 36 |

| 9 | PTL | 36 | 15 | 24 | 30 |

| 10 | Preeclampsia | 35 | 33 | ||

| 11 | Preeclampsia | 28 | 12 | ||

| 12 | Other | 27 | 20 | ||

| 13 | Preeclampsia | 35 | 14 | 32 | |

| 14 | Other | 33 | 8 | 17 | 32 |

| 15 | Fetal | 36 | 15 | 35 | |

| 16 | Preeclampsia | 35 | 8 | 15 | 30 |

| 17 | Preeclampsia | 33 | 16 | 30 | |

| 18 | Preeclampsia | 35 | 16 | 33 | |

| 19 | Preeclampsia | 34 | 15 | 28 | |

| 20 | Preeclampsia | 32 | 12 | 14 | 28 |

| 21 | Preeclampsia | 32 | 10 | 21 | |

| 22 | Fetal | 32 | 16 | ||

| 23 | Preeclampsia | 36 | 33 | ||

| 24 | Preeclampsia | 35 | 33 |

PTL = preterm labor

PROM = preterm rupture of membranes

Vaginal community characteristics of pregnancies with term and preterm delivery

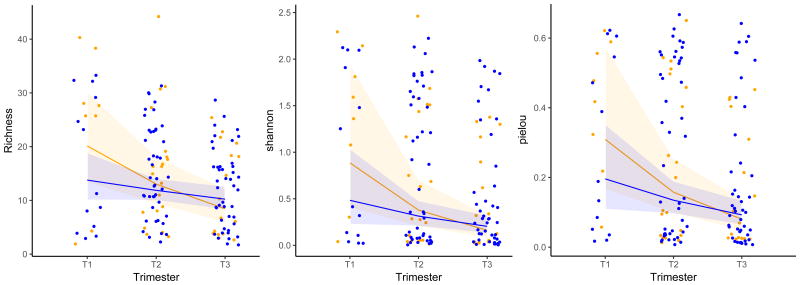

Alpha diversity statistics of the vaginal community in women with term and preterm birth are demonstrated in Figures 1 and 2. In both groups there is a visually perceptible downward trend as pregnancy progressed. However, among women who delivered at term, vaginal community richness and Shannon diversity remained stable (p=0.14 and p=0.07), and Pielou's evenness decreased modestly (p=0.04) (Figure 1 Blue). In contrast to the relatively stable richness and diversity noted in vaginal community content in women whose pregnancies ended at term, in women who subsequently delivered preterm richness (p<0.001), Shannon diversity (p<0.001) and Pielou's evenness (p<0.001) decreased significantly over pregnancy (Figure 1 Yellow).

Figure 1. Community Richness, Shannon Diversity, and Pielou Evenness (Genus Level) In All Subjects.

Legend: Richness, Shannon Diversity, and Pielou evenness (genus level V1V3) of the full cohort.

Blue = term birth Yellow = preterm birth

Lines represent regression lines from mixed models

Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals

Term birth shows stable richness (p=0.14) and stable Shannon Diversity (p=0.07). Pielou evenness decreases slightly (p=0.04) over pregnancy.

Preterm birth shows significant decrease in richness (p<0.001), Shannon Diversity (p<0.001), and Pielou evenness (p<0.001) over pregnancy.

Term versus preterm birth in single trimester comparisons showed no significant difference in pairwise comparisons within a single trimester.

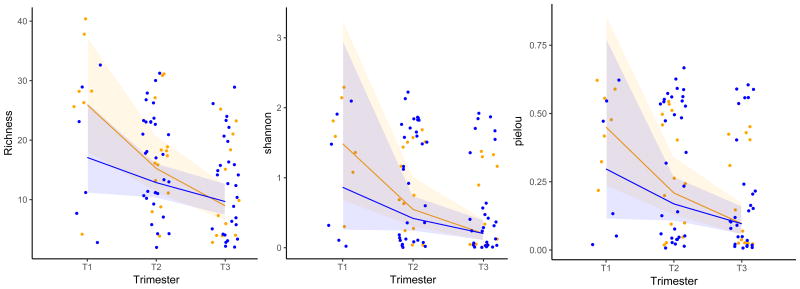

Figure 2. Community Richness, Shannon Diversity, and Pielou Evenness (Genus Level) In African-American Subjects.

Legend: Richness, Shannon Diversity, and Pielou evenness (genus level V1V3) of the African American cohort.

Blue = term birth Yellow = preterm birth

Lines represent regression lines from mixed models

Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals

Term birth shows stable richness (p=0.11), stable Shannon Diversity (p=0.09), and stable Pielou evenness (p=0.08) over pregnancy.

Preterm birth shows significant decrease in richness (p<0.001), Shannon Diversity (p=0.003), and Pielou evenness (p<0.001) over pregnancy.

Term versus preterm birth in single trimester comparisons showed no significant difference in pairwise comparisons within a single trimester.

Vaginal community richness, diversity, and evenness remained stable in the subgroup of African-American women who gave birth at term (p=0.11, p=0.09, and p=0.08 respectively) (Figure 2 Blue). In contrast, richness (p < 0.001), diversity (p=0.003), and Pielou evenness (p<0.001) significantly decreased across pregnancy in African-American women who delivered preterm (Figure 2 Yellow Bars). The timing of the decrease in alpha diversity appears to occur between trimester 1 and 2 in the overall cohort and in the subgroup of African-American women.

We next sought to determine if vaginal community alpha diversity indices in any single trimester of pregnancy differed between women who delivered preterm compared to those who delivered at term. In the overall cohort as well as in the African-American subgroup the greatest magnitude of difference between term and preterm birth occurred in the first trimester. In the full cohort, first trimester vaginal community richness, Shannon diversity, and Pielou's evenness was greater in women who subsequently delivered preterm, but the cross-sectional differences at this single time point alone were not statistically significant (p=0.4, p=0.3, p=0.3 respectively (Figure 1—Blue versus Yellow Dots-first trimester). Likewise, in the African-American subgroup, first trimester samples from women with subsequent preterm birth followed the same pattern with higher absolute richness, diversity, and evenness compared to first trimester samples with subsequent term birth but these comparisons were not statistically different (Figure 2—Blue versus Yellow dots—first trimester). Alpha diversity pairwise comparisons in the second and third trimesters did not differ between women whose pregnancies ended prematurely versus those whose pregnancies went to term, in both the total cohort and the subgroup of African-American women. The V3V5 amplicon alpha diversity analysis demonstrated identical patterns to those from the V1V3 amplicon and are provided in Supplemental Maternal (Supplemental Figures 2 and 3).

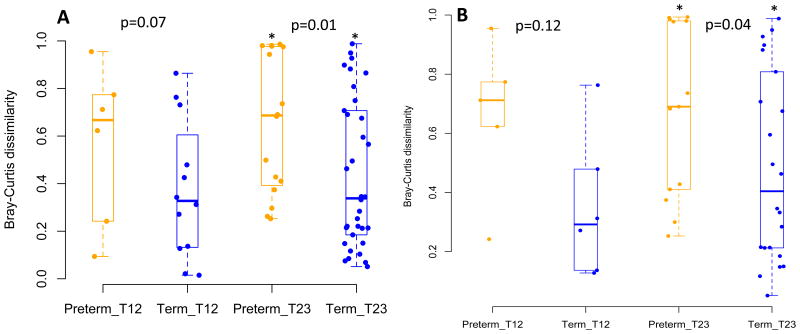

Figure 3. Bray Curtis Dissimilarity Within Subjects Across Pregnancy.

Legend: Bray Curtis dissimilarity for (A) entire cohort and (B) African American cohort for subjects with paired samples in trimester 1 and 2 and paired samples in trimester 2 and 3. Yellow = preterm birth Blue = term birth. In both the full cohort and the African American cohort preterm birth samples show significantly more dissimilarity to each other in the second and third trimesters than term birth samples suggesting that preterm birth outcomes are associated with a less stable vaginal community.

Characteristics of vaginal microbial community in non-African-American women

Because our population was predominantly African-American, the numbers of specimen and preterm birth outcomes in women of non-African American backgrounds were too small for meaningful statistical analyses. Nonetheless, despite the constraints of the sample size, the trends in the non-African-American women did differ from those in the African-American women with overall lower richness and diversity (Supplement Figure 4).

Beta-Diversity Measures: Within Subject Vaginal Microbiome Stability Over Pregnancy

We next examined stability of the vaginal microbiome in subjects with paired first and second trimester swabs and those with paired second and third trimester swabs using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity. There was a trend toward greater instability in vaginal communities between trimester 1 and trimester 2 in women with preterm birth compared to term birth, but the differences were not statistically significant (Figure 3). However, there was significantly more instability between trimester 2 to trimester 3 in women with preterm birth than those with term birth in both the full cohort (p=0.01) Figure 3A) as well as the African-American cohort (p=0.04) (Figure 3B). These data suggest that preterm birth is associated with vaginal community instability.

Beta-diversity using NMDS plots did not demonstrate useful discrimination patterns between term and preterm birth in any trimester of pregnancy for V1V3 and V3V5 amplicons. Clusters of observations noted in NMDS plots contained outcomes of both term and preterm birth as well as both African American and non-African American subjects and were not significantly different by PERMANOVA testing (Supplemental Figure 5 V1V3 and Supplemental Figure 6 V3V5).

Taxon Abundance

We next examined whether specific taxa differed in women destined for preterm birth. In all trimesters of pregnancy, regardless of birth outcome and race, the dominant taxon is Lactobacillus, and predominantly L. iners and L. crispatus. Single Lactobacillus species examination demonstrated that abundances of specific Lactobacillus species were neither protective nor harmful in any trimester of pregnancy in association with preterm birth (Supplemental Figure 7). Additionally Gardnerella abundance was examined using V3V5 data and there were no significant differences in Gardnerella abundance in women with term versus preterm birth in any trimester (Supplemental Figure 8). Ureaplasma was marginally increased among African-American women in trimesters 2 (p=0.07) and 3 (p=0.09) among those who delivered preterm (Supplemental Figure 9). However, no single taxon comparison in any trimester of pregnancy was statistically significantly associated with term or preterm birth outcomes.

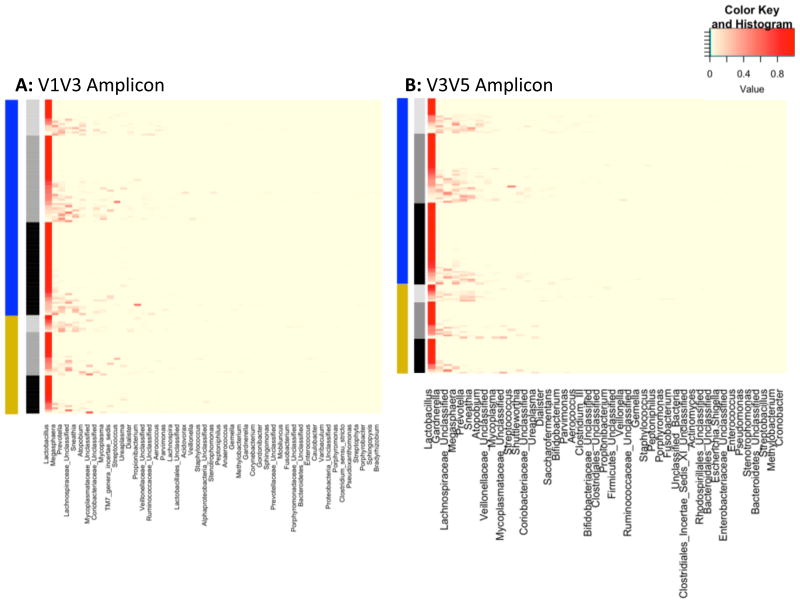

We used heat maps to visualize taxonomic composition clustered by term and preterm birth outcomes as well as by trimester of pregnancy according to V1V3 and V3V5 data (Figure 4). Both Lactobacillus-dominant and Lactobacillus-poor communities occur in all trimesters of pregnancy and in samples from both term and preterm birth outcomes. In highly Lactobacillus-dominant communities (dark red Lactobacillus bar) there were fewer rare taxa present whereas in Lactobacillus-poor communities (lighter red to yellow Lactobacillus bar) other taxa such as Prevotella, Sneathia, Atopobium, Mycoplasma and other taxa are more abundant. Gardnerella was more commonly detected in low Lactobacillus abundance communities (Figure 4 Panel B).

Figure 4. Heat map of all samples in cohort clustered by term and preterm birth and trimester of pregnancy.

Legend: Heat map of all samples from cohort showing all organisms comprising at least 1% of the community. Panel A V1V3 amplification, Panel B V3V5 amplification.

Left bar: blue=term birth, yellow= preterm birth.

Right bar: light gray=trimester 1, medium gray=trimester 2, black=trimester 3.

Histogram: darkest red = highest abundance, shades of red =relatively less abundance, pale yellow=low abundance or not present.

This heatmap demonstrates Lactobacillus dominant communities and Lactobacillus poor communities are present in all trimesters of pregnancy and in both term and preterm birth outcomes. In the most Lactobacillus dominant communities there is a paucity of other taxa present whereas in Lactobacillus poor communities there is a higher abundance of other taxa such as Prevotella, Sneathia, Atopobium, Mycoplasma and others. Gardnerella abundance (seen best in panel B) is more common in Lactobacillus poor communities.

Discussion

In this large, predominantly African-American cohort of pregnant women sampled across multiple trimesters, we found the vaginal bacterial community in women whose pregnancies ended at term demonstrated stability of richness and diversity during pregnancy, while in women with subsequent preterm birth, community richness and diversity significantly decreased early in pregnancy. The inflection point for change in richness and diversity associated with preterm birth appears to be between the first and the second trimesters with a pattern of higher alpha diversity noted in the first trimester. Additionally within-subject serial vaginal samples in women with subsequent preterm birth were more dissimilar than in women who delivered at term, suggesting that the vaginal microbiome associated with preterm birth may be less stable than that associated with term birth. The low diversity communities were comprised almost entirely of Lactobacillus species whereas high diversity communities contained Lactobacillus of varying abundance but also contained taxa such as Lachnospiraceae, Atopobium, Prevotella, Megasphaera, Sneathia, Mycoplasma, and Gardnerella. However, no specific taxon or taxa distinguished preterm from term births.

DiGiulio et al recently reported the absence of longitudinal changes in the vaginal microbiome during pregnancy21. Their cohort had fewer subjects, only two African-American women, and only 15 women delivered preterm, though they employed a more frequent sampling strategy. In contrast, we identified a candidate signature for preterm birth with an association between changing community diversity and instability over pregnancy in preterm birth, with the most pronounced changes occurring among African-American women. In view of the known racial influence on vaginal microbial content 16, 19, 27, these inter-study differences might be explained by the different demographic composition of the study populations. Notably, the Shannon diversity scores reported by DiGiulio et al resemble the correspondingly low scores we noted in our non-African-American population (Supplement Figure 2). Similar to our findings, their data suggest that vaginal communities associated with preterm birth were detectable early in pregnancy, suggesting that early pregnancy may be an important ecological time in the vaginal community. Our data also suggest that early vaginal community fluctuation may be a marker for preterm birth, and changes may not immediately precede preterm delivery.

Even with evidence of a significant change in richness and diversity associated with preterm birth, single trimester time-point comparisons alone were not informative. Additionally, within subject analysis of beta-diversity suggests less similarity or more instability of serial samples within a women with preterm birth compared to those in a woman with term birth. This suggests that predicting preterm birth from vaginal microbiome community structure is not as simple as finding a highly diverse community, specific community type, or specific taxa at a single time point in pregnancy, and that kinetics of community composition need to be considered.

Our data, like those of previous investigations 20 identify no single taxon or community of taxa that correlates exactly with pregnancy outcome. Romero et al analyzed multiple bacterial phylotypes and found than no specific bacterial phylotype was associated with preterm birth. Likewise in our taxa abundance analyses neither Lactobacillus species abundance nor other rarer taxa in Lactobacillus poor communities such as Gardnerella were individually significant markers for preterm birth. While Ureaplasma was increased in the second and third trimesters of African American women who subsequently delivered preterm, the difference was not statistically significant. Also while the change noted in Ureaplasma could be attributed to chance, it is intriguing that Ureaplasma, found in higher abundance in women with preterm birth in this cohort, has previously been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes including preterm birth 28-34. However, our current data suggest that the presence, absence, or abundance of specific taxa alone is not categorically sufficient for the prediction of subsequent term or preterm birth.

Our cohort's high proportion of preterm births adds to the literature on the association between changes in the vaginal microbial community and preterm birth. The high proportion of African-American women is a unique and informative feature of our analysis, especially as prior studies included predominantly non-African-American subjects. However, we acknowledge several study limitations. As with any observational study, differences between groups reflect associations and not necessarily causation. While our sample size is similar to or larger than those in prior studies, it was still too small to allow reliable statistical comparisons among non-African-American women. Nonetheless, the low diversity scores noted even in the small population of non-African-American patients of our study cohort is consistent with data from predominantly non-African-American populations in other reports 19, 21, and warrants further analysis.

We obtained the fewest samples from women in their first trimester, but based on our findings it appears to be an important time frame to study the vaginal microbiome for differences relevant to preterm birth. It is possible that the first trimester single time point comparisons which were not significantly associated with preterm birth may be underpowered. Likewise the beta-diversity measures examining stability from trimester 1 to trimester 2 also may be underpowered. The importance of the first trimester is illuminated both in this study as well as by DiGiulio et al 21, and highlights the need for future studies to adequately sample women early in pregnancy. Although women enrolled in the first trimester were clinically similar to those enrolled later in pregnancy it is unknown whether there are systematic differences in the microbiology of women who present for obstetric care earlier in gestation. Also, we included all preterm births in our analysis. While vaginal microbiological abnormalities are classically associated with spontaneous preterm birth, spontaneous and indicated preterm births are competing outcomes, and are not always accurately categorized 35. Additionally, our understanding of the association between vaginal bacterial communities and adverse pregnancy outcomes is still in its infancy. For these reasons, we chose a more general and agnostic approach to analyzing all preterm births, regardless of reason for the delivery.

In summary, this large cohort study of predominantly African-American pregnant women sampled longitudinally throughout pregnancy shows that a significant decrease in community richness and diversity, and less stability of the vaginal microbiome is associated with preterm birth. Future studies should focus on the first to second trimester microbial changes, well in advance of the outcome of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Monica Anderson, Michele Landeau, and Dina Kaissi for their assistance with this research (Employment: Washington University in Saint Louis Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Division of Clinical Research).

Financial Support: Dr. Stout has support from NICHD T32 (5 T32 HD055172-02), Washington University CTSA grant (UL1 TR000448), NIH/NICHD Women's Reproductive Health Research Career Development Program at Washington University in St. Louis (5K12HD063086-05), and The March of Dimes Prematurity Research Center at Washington University in Saint Louis. Dr. Tuuli has support from NIH/NICHD Women's Reproductive Health Research Career Development Program at Washington University in St. Louis (5K12HD063086-05). Dr. Tarr has support from the Digestive Diseases Research Core Center (P30DK052574 (Biobank Core)) and UH3 AI083265. The above funding sources had no role in the study design, collection/analysis/interpretation of data, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Human Subjects Approval: Washington University Institutional Review Board #201202015

Public Sharing of Data: These data will be available under Bioproject PRJNA294119. Data submission is in progress and the accession numbers will be provided prior to publication.

Condensation: In a predominantly African-American population, significant decrease of vaginal bacterial diversity between the first and second trimester is associated with preterm birth.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Mathews TJ, Osterman MJ. Births: final data for 2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;59(1):3–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creasy Rk RRIJDLCJMTM. Maternal-Fetal Medicine Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; Number of pages. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Mercer B, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: association of second-trimester genitourinary chlamydia infection with subsequent spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:662–8. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meis PJ, Goldenberg RL, Mercer B, et al. The preterm prediction study: significance of vaginal infections. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1231–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Cassen E, Easterling TR, Rabe LK, Eschenbach DA. The role of bacterial vaginosis and vaginal bacteria in amniotic fluid infection in women in preterm labor with intact fetal membranes. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(Suppl 2):S276–8. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.supplement_2.s276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Eschenbach DA, et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1737–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray DJ, Robinson HB, Malone J, Thomson RB., Jr Adverse outcome in pregnancy following amniotic fluid isolation of Ureaplasma urealyticum. Prenat Diagn. 1992;12:111–7. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970120206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero R, Espinoza J, Goncalves LF, Kusanovic JP, Friel L, Hassan S. The role of inflammation and infection in preterm birth. Seminars in reproductive medicine. 2007;25:21–39. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-956773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero R, Mazor M, Wu YK, et al. Infection in the pathogenesis of preterm labor. Semin Perinatol. 1988;12:262–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eschenbach DA, Nugent RP, Rao AV, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of erythromycin for the treatment of Ureaplasma urealyticum to prevent premature delivery. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:734–42. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90506-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carey JC, Klebanoff MA, Hauth JC, et al. Metronidazole to prevent preterm delivery in pregnant women with asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:534–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002243420802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenyon SL, Taylor DJ, Tarnow-Mordi W. Broad-spectrum antibiotics for spontaneous preterm labour: the ORACLE II randomised trial. ORACLE Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2001;357:989–94. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flenady V, Hawley G, Stock OM, Kenyon S, Badawi N. Prophylactic antibiotics for inhibiting preterm labour with intact membranes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000246.pub2. CD000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klebanoff MA, Carey JC, Hauth JC, et al. Failure of metronidazole to prevent preterm delivery among pregnant women with asymptomatic Trichomonas vaginalis infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:487–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;108(Suppl 1):4680–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aagaard K. Metagenomic-based approach to a comprehensive characterization of the vaginal microbiome signature in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011:S42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romero R, Hassan SS, Gajer P, et al. The composition and stability of the vaginal microbiota of normal pregnant women is different from that of non-pregnant women. Microbiome. 2014;2:4. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyman RW, Fukushima M, Jiang H, et al. Diversity of the Vaginal Microbiome Correlates With Preterm Birth. Reproductive sciences. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1933719113488838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romero R, Hassan SS, Gajer P, et al. The vaginal microbiota of pregnant women who subsequently have spontaneous preterm labor and delivery and those with a normal delivery at term. Microbiome. 2014;2:18. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiGiulio DB, Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, et al. Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:11060–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502875112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aagaard K, Petrosino J, Keitel W, et al. The Human Microbiome Project strategy for comprehensive sampling of the human microbiome and why it matters. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2013;27:1012–22. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-220806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Human Microbiome Project C. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–14. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jumpstart Consortium Human Microbiome Project Data Generation Working G. Evaluation of 16S rDNA-based community profiling for human microbiome research. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frank JA, Reich CI, Sharma S, Weisbaum JS, Wilson BA, Olsen GJ. Critical evaluation of two primers commonly used for amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:2461–70. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02272-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Y, Gao H, Mihindukulasuriya KA, et al. Biogeography of the ecosystems of the healthy human body. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fettweis JM, Brooks JP, Serrano MG, et al. Differences in vaginal microbiome in African American women versus women of European ancestry. Microbiology. 2014;160:2272–82. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.081034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson DB, Hanlon A, Nachamkin I, et al. Early pregnancy changes in bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria and preterm delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014;28:88–96. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiGiulio DB. Diversity of microbes in amniotic fluid. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine. 2012;17:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han YW, Shen T, Chung P, Buhimschi IA, Buhimschi CS. Uncultivated bacteria as etiologic agents of intra-amniotic inflammation leading to preterm birth. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:38–47. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01206-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kundsin RB, Leviton A, Allred EN, Poulin SA. Ureaplasma urealyticum infection of the placenta in pregnancies that ended prematurely. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:122–7. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, Goepfert AR, et al. The Alabama Preterm Birth Study: umbilical cord blood Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis cultures in very preterm newborn infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:43e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aaltonen R, Heikkinen J, Vahlberg T, Jensen JS, Alanen A. Local inflammatory response in choriodecidua induced by Ureaplasma urealyticum. BJOG. 2007;114:1432–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stout MJ, Busam R, Macones GA, Tuuli MG. Spontaneous and indicated preterm birth subtypes: interobserver agreement and accuracy of classification. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:530e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.