Abstract

Background

Inadequate or excessive total gestational weight gain (GWG) is associated with increased risks of small- and large-for-gestational age births, respectively, but evidence is sparse regarding overall and trimester-specific patterns of GWG in relation to these risks. Characterizing the interrelationship between patterns of GWG across trimesters can reveal whether the trajectory of GWG in the 1st trimester sets the path for GWG in subsequent trimesters, thereby serving as an early marker for at-risk pregnancies.

Objective

Describe overall trajectories of gestational weight gain across gestation and assess the risk of adverse birthweight outcomes associated with the overall trajectory and whether the timing of GWG (1st trimester versus 2nd/3rd trimester) is differentially associated with adverse outcomes.

Study Design

A secondary analysis of a prospective cohort of 2,802 singleton pregnancies from 12 U.S. prenatal centers (2009–2013). Small- and large-for-gestational age were calculated using sex-specific birth weight references <5th, <10th or ≥90th percentiles, respectively. At each of the research visits, women’s weight was measured following a standardized anthropometric protocol. Maternal weight at antenatal clinical visits was also abstracted from the prenatal records. Semiparametric, group-based, latent class, trajectory models estimated overall gestational weight gain and separate 1st and 2nd/3rd trimester trajectories to assess tracking. Robust Poisson regression was used to estimate the relative risk of small- and large-for-gestational age outcomes by the probability of trajectory membership. We tested whether relationships were modified by pre-pregnancy body mass index.

Results

There were 2,779 women with a mean (SD) of 15(5) weights measured across gestation. Four distinct gestational weight gain trajectories were identified based on the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) value, classifying 10.0%, 41.8%, 39.2%, and 9.0% of the population from lowest to highest weight gain trajectories, with an inflection at 14 weeks. The average rate in each trajectory group from lowest to highest for 0 to <14 weeks was −0.20, 0.04, 0.21, and 0.52 kg/week and for 14 to 39 weeks was 0.29, 0.48, 0.63, and 0.79 kg/week, respectively; the 2nd lowest gaining trajectory resembled the Institute of Medicine recommendations and was designated as the reference with the other trajectories classified as low, moderate-high or high. Accuracy of assignment was assessed and found to be high (median posterior probability = 0.99, interquartile range 0.99–1.00). Compared with the referent trajectory, a low overall trajectory, but not other trajectories, was associated with a 1.55-fold (95% CI: 1.06, 2.25) and 1.58-fold (95% CI: 0.88, 2.82) increased risk of small-for-gestational age <10th and <5th, respectively, while a moderate-high and high trajectory, were associated with a 1.78-fold (95% CI: 1.31, 2.41) and 2.45-fold (95% CI: 1.66, 3.61) increased risk of large-for-gestational age, respectively. In a separate analysis investigating whether early (< 14 weeks) gestational weight gain tracked with later (≥ 14 weeks) gestational weight gain, only 49% (n=127) of women in the low 1st trimester trajectory group continued as low in the 2nd/3rd trimester, and had a 1.59-fold increased risk of small-for-gestational age; for the other 51% (n=129) of women without a subsequently low 2nd/3rd trimester gestational weight gain trajectory, there was no increased risk of small-for-gestational age (RR=0.75, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.38). Pre-pregnancy body mass index did not modify the association between gestational weight gain trajectory and small-for-gestational age (p=0.52) or large-for-gestational age (p=0.69).

Conclusion

Our findings are reassuring for women who experience weight loss or excessive weight gain in the first trimester; however, the risk of small- or large-for-gestational age is significantly increased if women gain weight below or above the reference trajectory in the 2nd/3rd trimester.

Keywords: Birth weight, gestational weight gain, patterns, small-for-gestational-age, trajectory

Introduction

Gestational weight gain (GWG) has gained particular interest in public health as a potentially modifiable factor to ensure healthy pregnancy outcomes and reduce the risk of adverse outcomes.1 The intense interest in GWG was in part prompted by gaps identified in the 2009 Institute of Medicine report on reexamining the GWG guidelines.1 While total GWG provides a long-term goal for pregnant women, the pattern of GWG throughout pregnancy has stronger clinical utility as a prospective monitoring tool for clinicians to identify weight gain above or below the guidelines, early on, when intervening may still benefit both mother and baby. Yet, few studies, in homogenous populations, informed the recommended 2nd/3rd trimester rates of gain2–4 and provide little insight into the impact of 1st trimester patterns in relation to birthweight outcomes. The current guidelines may obscure how varying trajectories of 1st trimester weight gain impact 2nd/3rd trimester patterns.5 Recent evidence, aimed at addressing these data gaps, supports the notion that women may reach total GWG through various weight gain trajectories6–8 and suggests that higher trimester-specific GWG is associated with a decreased odds of small-for-gestational age (SGA) and increased odds of large-for-gestational age (LGA).9–11 However, the majority of this evidence assessed each trimester independently, as opposed to assessing the entire trajectory of GWG throughout pregnancy. It also remains unclear whether early pregnancy GWG (e.g. 1st trimester) sets the trajectory for subsequent 2nd/3rd trimester GWG or if a fluctuating trajectory of GWG across trimesters differentially affects the risk of birthweight outcomes. For example, if GWG is low in the 1st trimester, but rapid in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters, does the risk of SGA differ compared with a low GWG trajectory throughout pregnancy? By characterizing the interrelationship between trajectory of GWG across trimesters, we can discover whether the trajectory of GWG in the 1st trimester sets the path for GWG in subsequent trimesters, serving as an early marker for at-risk pregnancies.

Our objectives were first to describe overall GWG trajectories in a contemporary, diverse, U.S. cohort. Secondly, we aimed to calculate the risk of birthweight outcomes (SGA, LGA, SGA or LGA plus neonatal morbidity) associated with overall trajectory of GWG. Lastly, we aimed to examine the effect of an early (1st trimester) versus later (2nd/3rd trimester) GWG trajectory on the risk of subsequent birthweight outcomes, to assess whether the timing of GWG was differentially associated with adverse outcomes.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis using data from the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies – Singletons (n=2802), a prospective cohort of pregnant women aged 18–40 years with a pregnancy between 8 weeks 0 days and 13 weeks 6 days [mean (SD): 12.7 weeks (0.95)] of gestation from 12 U.S. sites between July 2009 and January 2013. The primary purpose of the original NICHD Fetal Growth study was to establish a standard for normal fetal growth (velocity) and size for gestational age in the U.S. population. Secondary objectives included a collection of blood samples for an etiology study of gestational diabetes and a prediction study of fetal growth restriction and/or overgrowth, and collection of dietary intake data to study the association between nutrition and fetal growth. To achieve the first objective, the study aimed to recruit 2,400 healthy, non-obese (BMI between 19.0–29.9 kg/m2), low risk women across four race/ethnicity groups, who conceived spontaneously and have no obvious risk factors for fetal growth restriction or overgrowth, specifically, non-Hispanic white, African-American, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander women (600 women in each group). In addition, the study aimed to recruit 600 obese women (BMI between 30 and 45 kg/m2) with no restriction on race/ethnicity in order to achieve the additional study aims. Exclusion criteria were similar between non-obese and obese women and included chronic hypertension or high blood pressure under medical supervision (obese women if requiring two or more medications), pregestational diabetes, chronic renal disease under medical supervision, autoimmune disease, psychiatric disorders, cancer, and HIV/AIDS 12. Additional exclusion criteria for the non-obese women included a history of preterm low birthweight (<2500 g), or macrosomic (>4000 g) neonate; history of stillbirth or neonatal death; medically assisted conception; cigarette smoking or illicit drug use in past 6 or 12 months, respectively; >1 daily alcoholic drinks; previous fetal congenital malformation; history of non-communicable diseases (asthma requiring weekly medication, epilepsy or seizures requiring medication, hematologic disorders, hypertension, thyroid disease); or history of gravid diseases (gestational diabetes, severe preeclampsia/eclampsia, or hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count syndrome).12 Only one pregnancy per mother was included in the cohort. Human subjects’ approval was obtained from all participating sites and women gave informed consent.

At enrollment, research nurses conducted in-person interviews to obtain detailed demographic and health characteristics. Recalled pre-pregnancy weight and measured height, using a portable stadiometer (Seca Corporation, Hamburg, Germany; US office, Hanover, MD), were used to calculate pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2). At each of the NICHD Fetal Growth research visits, women’s weight was measured following a standardized anthropometric protocol. Maternal weight at routine antenatal clinical visits was also abstracted from the prenatal records. In order to improve the precision of estimates by increasing the number of measurements per women, we evaluated the quality of abstracted weights from prenatal records to see if both the measured weights as part of the study protocol and chart abstracted weights from prenatal records could be combined. We calculated the rate of change between each weight and the next closest measurement, regardless of the source, to examine for large implausible gains/losses. A chart abstracted and measured research visit weight occurring on the same gestational age (to the day) were within a mean (SD; range) of 0.04 (0.95; −10.5- 14.5) kg (n=2169 duplicate weights out of 45,540, 4.7%) and were highly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.998); therefore, both sources of maternal weight were used in the analysis due to their high consistency. However, to avoid redundancy, in the instances where both weights occurred on the same day, we included only the measured weights in the analysis. Gestational weight gain was calculated as the difference between maternal weight and self-reported pre-pregnancy weight. The last maternal weight was measured at a mean (SD) of 39.2 (1.66) weeks. After delivery, certified staff abstracted maternal and neonatal information from the medical records. Birth weight at delivery was used to calculate SGA<10th and LGA ≥90th based on sex-specific birth weight references.13 Furthermore, in an effort to identify pathologically small or large infants, babies who are small due to underlying pathologic conditions and are at an increased risk of morbidity and mortality,14 we also created the following outcome measures: severe SGA (SGA<5th percentile), SGA<10th plus neonatal morbidity, and LGA≥90th plus neonatal morbidity. Neonatal morbidities were selected based on what was reported in the literature15 and data availability, and were defined specifically to SGA or LGA based on the likelihood of the relevant outcome and included: metabolic acidosis (pH <7.1 and base deficit >12mmol/L), NICU stay greater than three days, pneumonia, respiratory distress syndrome, persistent pulmonary hypertension, seizures, hyperbilirubinemia requiring exchange transfusion, intrapartum aspiration (meconium, amniotic fluid, blood), neonatal death, mechanical ventilation at term, necrotizing enterocolitis, hypoglycemia, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, periventricular leukomalacia (SGA only), sepsis based on blood culture (SGA only), bronchopulmonary dysplasia/chronic lung disease (SGA only), retinopathy of prematurity (SGA only), and birth injury (LGA only).16–20

Statistical Analysis

To estimate the GWG trajectories, we excluded 3 women who were ineligible after enrollment and were missing pre-pregnancy weight and included the remaining 2779 women with at least 2 weight measurements to improve model accuracy. We used a latent-class trajectory model, a flexible semi-parametric approach to discover patterns of GWG across pregnancy using PROC TRAJ in SAS.21 This method provides a data-driven approach to identify whether there are groups of latent trajectories and the corresponding probability of falling into each group (posterior probability). We fit linear, quadratic, and cubic models to allow for model flexibility and examined model fit with 3–6 trajectories. The model with the lowest Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) value was selected, as this value serves to indicate model fit.21 For descriptive analyses, women were classified into a particular trajectory group (trajectory membership) based on their highest posterior probability. Chi-squared tests and Fisher’s exact, where appropriate, were used to determine differences in maternal demographic characteristics by trajectory.

First, we fit the latent trajectory models to all the longitudinal data across pregnancy. To assess the tracking of weight gain, we then fit two separate latent trajectory models to longitudinal data collected in the first trimester (0 - <14 weeks) and the 2nd/3rd trimester (≥14 weeks to delivery), to inform the current 1st and 2nd/3rd trimester GWG guidelines. We classified subjects into four groups in each time period based on the separate latent trajectory models fit for the 1st and 2nd/3rd trimesters. Then, we calculated the proportion of women in each trajectory combination from the 1st to 2nd/3rd trimesters.

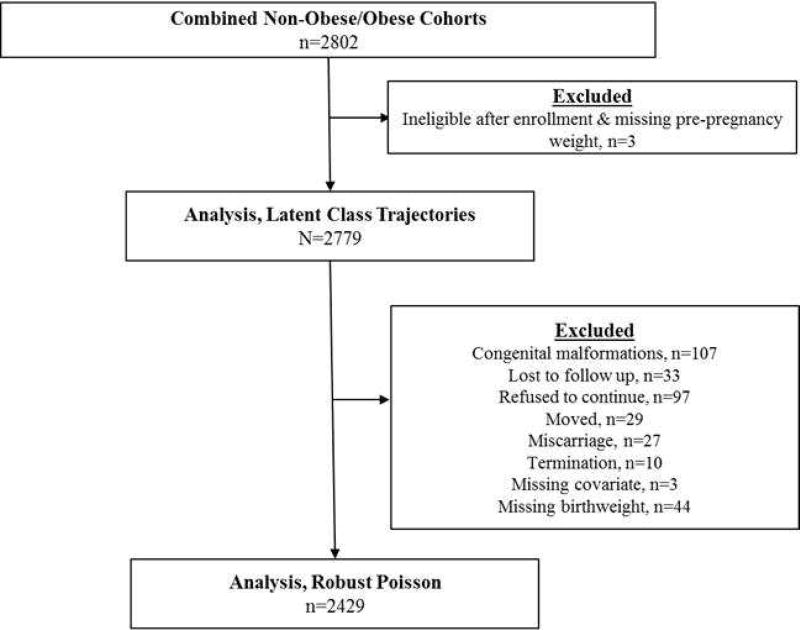

After the overall and trimester-specific GWG trajectories were estimated, we examined the association between the trajectories and birth weight outcomes. Among the 2779 women who were eligible for this analysis, we excluded women who had neonates with congenital anomalies (n=107), were lost to follow up (n=33), refused to continue (n=97), or moved (n=29), had stillbirth or miscarriage (n=27), voluntarily terminated (n=10) their pregnancy, had missing covariate information (n=3), or had missing birth weight (n=44). The final analysis included 2429 women (Figure 1). We fit modified Poisson regression models with a robust variance estimator using the overall posterior probabilities to assess the risk of SGA and LGA, as well as SGA and LGA plus neonatal morbidity. Models were adjusted for maternal age (<20, 20–29, 30–39, 40–44), pre-pregnancy BMI, height, parity (0, 1, ≥2), education level (≤ High School diploma, Some college or Associates degree, Bachelors or Advanced Degree), student status (yes/no), and race (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander). All covariates were treated as continuous unless otherwise stated (Supplemental Figure 1). We tested whether relationships were modified by pre-pregnancy BMI (tested both as continuous and categorical variables) or maternal race (likelihood ratio test conducted at the 0.05 significance level). In order to examine the differential associations of early versus later GWG (corresponding to the 1st and 2nd/3rd trimester, respectively) with the risk of subsequent birth weight outcomes, we used the separate trajectory models fit for these two time periods. Since the low and high GWG trajectories presented the most risk for birth weight outcomes, we were interested in assessing whether moving out of either a low or high trajectory changed the risk of birth outcomes. Therefore, we combined the remaining categories, since it was rare that an individual switched between low and high groups (n=1 from low to high GWG; n=0 from high to low GWG).

Figure 1.

Analytic flow diagram for the NICHD Fetal Growth Study-Singletons

The low and high GWG groups presented the most risk for birth weight outcomes; therefore, we characterized the effects of changing from each of these groups between the 1st and 2nd/3rd trimester using the following two classification schemes. First, in order to examine differential effects from the lowest GWG group, we classified subjects as being in one of the following four groups for the 1st to 2nd/3rd trimesters: referent to referent; low to low; low to referent or moderate-high or high; referent or moderate-high or high to low. Second, to examine differential effects from the highest GWG group we classified subjects as being in one of the following four groups for the 1st to 2nd/3rd trimesters: referent to referent; high to high; high to low or referent or moderate-high; low or referent or moderate-high to high.

Additionally, to assess the potential bias by pregnancy/birth complications or differences between non-obese and obese women, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to explore GWG trajectories in a subset of the cohort, the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies Standard12 (n=1731), restricted to a group of non-obese, low-risk women without specific pregnancy complications such as preterm birth, gestational diabetes, or preeclampsia, or infants with neonatal conditions such as anomalies, aneuploidy, or death. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, North Carolina, U.S.) and Stata software, version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

In the 2,779 women in the cohort, the majority were 20–39 years of age (93%), married (74.9%), and of normal weight (56.2%) (Table 1). The racial composition was evenly distributed as per study design between non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic women, although there was a smaller proportion of Asian women (16.1%). The mean (SD) number of measured weights per woman was 15 (5), which was comprised of both the measured [4.2 (0.99)] and abstracted [(11.3 (2.8)] weights.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the population by trajectory membership a, No. (%)

| Overall (n=2779) |

Low GWG No.(%) (n=274) |

Reference GWG No.(%) (n=1173) |

Moderate- High GWG No.(%) (n=1099) |

High GWG No.(%) (n=253) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age, yb | |||||

| <20 | 162 (5.7) | 31 (11.3) | 64 (5.4) | 54 (5.0) | 13 (5.3) |

| 20–29 | 1463 (52.3) | 165 (60.3) | 623 (53.1) | 535 (48.6) | 140 (55.1) |

| 30–39 | 1146 (41.0) | 77 (28.0) | 470 (40.0) | 499 (45.4) | 100 (39.6) |

| 40–44 | 28 (1.0) | 1 (0.4) | 16 (1.5) | 11 (1.0) | 0 (0) |

| Insuranceb | |||||

| Other | 973 (37.7) | 136 (53.0) | 418 (38.9) | 314 (30.8) | 105 (44.2) |

| Private or managed | 1611 (62.3) | 119 (47.0) | 663 (61.1) | 699 (69.2) | 130 (55.8) |

| Race/Ethnicityb | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 751 (26.8) | 41 (14.9) | 288 (24.4) | 355 (32.3) | 67 (26.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 781 (27.9) | 113 (41.2) | 297 (25.2) | 286 (26.0) | 85 (33.5) |

| Hispanic | 801 (28.6) | 98 (35.8) | 360 (30.9) | 271 (24.6) | 72 (28.5) |

| Asian and Pacific Islander | 466 (16.7) | 22 (8.0) | 228 (19.5) | 187 (17.1) | 29 (11.5) |

| Marital Statusb | |||||

| Never Married | 632 (22.5) | 83 (30.3) | 263 (22.4) | 219 (19.8) | 67 (26.5) |

| Married | 2082 (74.5) | 181 (66.1) | 881 (75.0) | 850 (77.3) | 170 (67.2) |

| Divorced/Widowed | 83 (3.0) | 10 (3.6) | 27 (2.4) | 30 (2.9) | 16 (6.3) |

| Educationb | |||||

| ≤ High School diploma | 838 (29.9) | 119 (43.1) | 371 (31.5) | 273 (24.9) | 75 (29.7) |

| Some college or Associates degree | 850 (30.4) | 102 (37.6) | 326 (27.7) | 319 (29.0) | 103 (40.7) |

| Bachelors or Advanced Degree | 1111 (39.7) | 53 (19.3) | 476 (40.8) | 502 (46.1) | 75 (29.6) |

| Incomeb | |||||

| <$39,000 | 943 (39.0) | 132 (56.4) | 381 (37.9) | 342 (35.3) | 83 (41.5) |

| $40–74,900 | 527 (21.8) | 63 (26.9) | 214 (21.3) | 199 (20.5) | 51 (24.6) |

| >$75 | 945 (39.1) | 39 (16.7) | 410 (40.8) | 428 (44.2) | 68 (33.9) |

| Parityb | |||||

| 0 | 1316 (47.0) | 105 (38.3) | 536 (45.6) | 543 (49.4) | 132 (52.2) |

| 1 | 943 (33.7) | 97 (35.4) | 406 (34.7) | B) 372 (33.8) | 68 (26.9) |

| >2 | 540 (19.3) | 72 (26.3) | 231 (19.7) | 184 (16.8) | 53 (20.9) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMIb | |||||

| Normal Weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 1575 (56.3) | 78 (28.5) | 695 (59.3) | 684 (62.4) | 117 (46.6) |

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 750 (26.8) | 81 (29.6) | 289 (24.7) | 285 (25.9) | 95 (37.3) |

| Obese (>30.0 kg/m2) | 474 (16.9) | 115 (41.9) | 188 (16.0) | 130 (11.7) | 41 (16.2) |

| Preterm Birthb | |||||

| <37 weeks | 2290 (94.3) | 21 (8.80) | 56 (5.50) | 45 (4.70) | 17 (7.80) |

| ≥37 weeks | 139 (5.70) | 21 (91.2) | 968 (94.5) | 905 (95.3) | 200 (92.2) |

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index; GWG, Gestational Weight Gain

Gestational weight gain trajectories identified from latent class trajectory models and women grouped based on highest probability of group membership; median (IQR) posterior probability, 0.99 (0.99, 1.0) for all groups.

Chi-square Test or Fishers Exact p-value<0.05 for differences in demographic characteristics across GWG trajectory groups

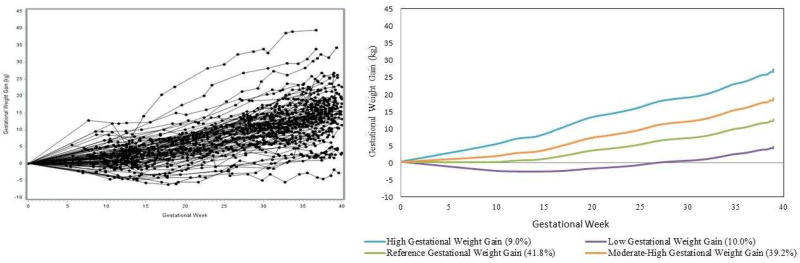

Figure 2 depicts the raw GWG trajectories from a random sample of 100 women (Figure 2A) in comparison with the modeled latent trajectory data (Figure 2B) to illustrate the accurate fit of the latent models. The latent class trajectory approach identified a cubic model with four distinct weight gain trajectory groups, classifying 10.0%, 41.8%, 39.2%, and 9.0% of the population from lowest to highest weight gain trajectories, with an inflection point at 14 weeks gestation (Figure 2). The average rate in each trajectory group from lowest to highest for 0 to <14 weeks was −0.20, 0.04, 0.21, and 0.52 kg/week and for 14 to 39 weeks was 0.29, 0.48, 0.63, and 0.79 kg/week (Table 2). The 2nd lowest gaining trajectory most closely resembled the IOM GWG recommendations for normal weight women1 and was therefore designated as the reference GWG group, with the other trajectories classified as low, moderate-high or high. In the analysis limited to the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies – Singleton standard,12 comprised of 1,737 non-obese women at low-risk for fetal growth abnormalities, the latent class trajectory approach identified only two trajectories that approximated the reference and moderate-high trajectories (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A) Random sample of 100 raw gestational weight gain trajectories B) Identified gestational weight gain trajectories from latent class model.

Legend: Separate colors indicate different gestational weight gain classes.

Table 2.

Trimester-specific rate of gestational weight gain corresponding to entire pregnancy trajectories in Figure 2.

| 1st Trimester (0- <14 weeks) Mean (95% CI) |

2nd + 3rd Trimester (>14 weeks to Delivery) Mean (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Rate of Gain (kg/week) |

Rate of Gain (kg/week) |

|

|

|

||

| Low GWG | −0.20 (−0.19, −0.21) | 0.29 (0.28, 0.30) |

| Reference GWG | 0.04 (0.04, 0.05) | 0.48 (0.47, 0.48) |

| Moderate-High GWG | 0.21 (0.21, 0.22) | 0.63 (0.63, 0.64) |

| High GWG | 0.52 (0.51, 0.53) | 0.79 (0.79, 0.80) |

The latent class trajectory models also assessed the accuracy of assignment (i.e., the posterior probability) of each individual woman to one of the four groups. For all individuals, the median posterior probability of assignment to a given class was 0.99 (IQR=0.99–1.0), indicating confidence in the classification.

Demographic characteristics differed by overall GWG groups (Table 1). Compared with the reference and moderate-high GWG groups, women in the low GWG group were less likely to have private or managed insurance, to have income ≥ $75,000, have less education, and more likely to be non-Hispanic Black (Table 1). The prevalence of SGA <10th percentile decreased with increasing overall GWG trajectory group from 15.3% in the low GWG group to 5.2% in the high GWG group. In contrast, the percent of LGA ≥90th percentile increased with increasing GWG class from 3.7% to 16.9% for the low GWG to high GWG group (Table 3).

Table 3.

The prevalence of birthweight outcomes by gestational weight gain trajectory group

| Low GWG No.(%) (n=274) |

Reference GWG No.(%) (n=1173) |

Moderate- High GWG No.(%) (n=1099) |

High GWG No.(%) (n=253) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small for Gestational Age (SGA) | ||||

| SGA <10th % a | 37 (15.3) | 103 (10.3) | 69 (7.9) | 10 (5.2) |

| SGA <5th % a | 17 (6.9) | 51 (4.9) | 29 (3.1) | 6 (2.9) |

| SGA<10th % plus neonatal morbidity | 3 (1.5) | 6 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (1.2) |

| Large for Gestational Age (LGA) | ||||

| LGA ≥90th % a | 8 (3.7) | 67 (6.9) | 114 (12.3) | 37 (16.9) |

| LGA≥90th % plus neonatal morbidity | 0 (0) | 3 (0.35) | 7 (0.90) | 2 (1.2) |

Abbreviation: GWG, Gestational Weight Gain; SGA, small-for-gestational age; LGA, large-for-gestation age; BW, Birthweight

Chi-square Test or Fishers Exact p-value<0.001 for group differences

Compared with a reference GWG trajectory across the entire pregnancy, low GWG was associated with a 55% increased risk of SGA<10th percentile (RR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.06, 2.25) and a 62% decreased risk of LGA (RR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.17, 0.85). A similar trend was observed for SGA<5th percentile and SGA plus neonatal morbidity, although none of the estimates were significant. A high GWG trajectory was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk of LGA (Table 4). The sample size was too small to accurately estimate the risk of LGA plus neonatal morbidity. The low GWG trajectory was comprised of 42% of obese women, although that only accounted for 24.3% (n=115) of obese women in the study; obese women comprised 39.7% of the reference, 27.4% of the moderate-high and 8.6% of the high GWG trajectories. When we evaluated whether pre-pregnancy BMI modified the association between GWG trajectory and risk of adverse birthweight outcomes, there was no effect: SGA<10th percentile (p=0.52), SGA<5th percentile (p=0.61), SGA plus neonatal morbidity (p=0.60), or LGA≥90th percentile (p=0.69); therefore, we did not stratify our results by pre-pregnancy BMI. Similarly, since relations did not vary by race/ethnicity, we did not stratify our results.

Table 4.

The risk of birthweight outcomes by gestational weight gain trajectorya

| Percent in each group |

SGA <10th percentile plus neonatal morbidity b RR (95% CI) |

SGA <5th percentile b RR (95% CI) |

SGA <10th percentile b RR (95% CI) |

LGA ≥ 90th percentile b RR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||||

| Low GWG | 10.0 | 1.56 (0.28, 8.69) | 1.58 (0.88, 2.82) | 1.55 (1.06, 2.25) | 0.38 (0.17, 0.85) |

| Reference GWG | 41.8 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Moderate-High GWG | 39.2 | 0.51 (0.12, 2.10) | 0.57 (0.35, 0.94) | 0.75 (0.55, 1.02) | 1.78 (1.31, 2.41) |

| High GWG | 9.0 | 1.14 (0.19, 6.82) | 0.50 (0.19, 1.27) | 0.51 (0.25, 1.00) | 2.45 (1.66, 3.61) |

Abbreviation: GWG, Gestational Weight Gain; SGA, Small-for-gestational age; LGA, Large-for-gestational age;

Corresponds to latent trajectory posterior probabilities

Model 1: adjusted for insurance, race, student status, education, parity, height, pre-pregnancy BMI, age

Table 5 depicts GWG tracking from the 1st to 2nd/ 3rd trimesters. Among women with low GWG in the 1st trimester, 49.6% continued to have low GWG in the 2nd/3rd trimesters, while 45% and 5.4% increased their GWG trajectory to the reference GWG or moderate-high GWG, respectively. Among the 52 women with high GWG in the 1st trimester, a high proportion (75%) continued to have high GWG until delivery. Among women with reference GWG in the 1st trimester, most gained in the reference (46%) or moderate-high (44%) in the 2nd/3rd trimesters; while, approximately one third (35%) of women with moderate-high weight gain in the 1st trimester had high GWG in the 2nd/3rd trimesters.

Table 5.

The proportion of women in each GWG trajectory from 1st trimester gestational weight gain to2nd/3nd trimesters

|

2nd/3rd Trimester Trajectorya

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1st Trimester Trajectorya |

Low GWG | Reference GWG | Moderate-High GWG |

High GWG |

| Low GWG | 127/256 (49.6%) | 114/256 (44.5%) | 14/256 (5.5%) | 1/256 (0.4%) |

| Reference GWG | 83/1696 (5%) | 781/1696 (46%) | 737/1696 (44%) | 95/1696 (5%) |

| Moderate-High GWG | 4/436 (0.9%) | 45/436 (10.5%) | 238/436 (54.3%) | 149/436 (34.3%) |

| High GWG | 0/53 (0%) | 2/53 (3.8%) | 11/53 (21.2%) | 39/53 (75%) |

Women were each assigned a trajectory when their individual probability was >0.80 for a particular trajectory based on the latent class models. Women without an individual trajectory probability of >0.80 were classified to the trajectory with the highest posterior probability (n= 215 re-classified 1st trimester and n=108 re-classified 2nd/3rd trimester)

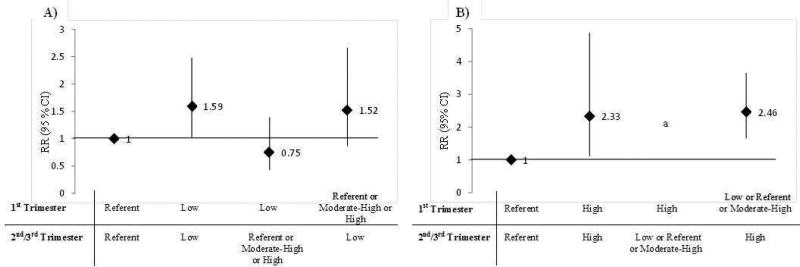

The risk of SGA differed based on the 1st to 2nd/3rd trimester pattern of GWG. Women with low GWG in both the 1st and 2nd/3rd trimesters had a 1.59- fold (95% CI: 1.04, 2.52) increased risk of SGA <10th percentile, compared with reference GWG in both periods. In contrast, women with a low GWG trajectory in the 1st trimester but referent, moderate-high, or high GWG trajectory in the a 2nd/3rd trimester had no increased risk of SGA. Women with low GWG only in the 2nd/ 3rd trimesters but not in the 1st had a 1.52-fold (95% CI: 0.87, 2.66) increased risk of SGA (Figure 3). For the risk of LGA, women with high GWG in both the 1st and 2nd/3rd trimesters had a 2.33-fold (95% CI: 1.11, 4.87) increased risk of LGA, and women with either a low, referent, or moderate-high trajectory in the 1st trimester, but high in the 2nd/3rd trimesters had a 2.46 (95% CI: 1.66, 3.65) increased risk of LGA. There were too few women with high GWG in the 1st trimester to obtain all estimates.

Figure 3.

The risk of small-for-gestational age (A) and large-for-gestational age (LGA) by the combined trajectory of GWG from the 1st to 2nd/3rd trimesters

Legend: Women were each assigned a trajectory when their individual probability was >0.80 for a particular trajectory based on the latent class models. Women without an individual trajectory probability of >0.80 were classified to the trajectory with the highest posterior probability (n= 215 re-classified 1st trimester and n=108 re-classified 2nd/3rd trimester)

a Missing estimates due to a small n

Discussion

In a modern, diverse cohort of pregnant women, four trajectories of overall GWG were evident. The gestational weight gain trajectory with a mean of 0.04 kg per week before 14 weeks and of 0.48 kg per week from 14 to 39 weeks of gestation was associated with the lowest risk of SGA or LGA. Women following a low GWG trajectory across the entirety of pregnancy had an increased risk of SGA while women with a high trajectory had an increased risk of LGA, suggesting the importance of the reference trajectory in balancing the risk of either outcome. The association between GWG and SGA and LGA was no longer evident when a low or high 1st trimester trajectory did not continue on the same low or high trajectory for the 2nd/3rd trimesters. These findings highlight that the risk of SGA was only increased based on 2nd/3rd trimester GWG. When only the 2nd/3rd trimester GWG trajectory was low, the risk of SGA was similar to when both the 1st and 2nd/3rd trimester trajectories were low and when only 2nd/3rd trimester GWG was high, the risk of LGA was similar to when both the 1st and 2nd/3rd trimester trajectories were high. Both of these findings underscore the importance of maternal GWG in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters.

The main new contribution of our study is the assessment of the interrelationship between the 1st and 2nd/3rd trimester trajectories on these risks. In a previous cluster analysis using a small, homogenous cohort of 325 healthy pregnant women from Belgium, four weight gain trajectories were identified and a dose-response relationship was reported between the overall GWG trajectory and birth weight at delivery.6 Compared with the trajectories identified by Galjaard et al. (2013), our trajectories were shifted upwards towards higher GWG, a difference that may be related to fact that the low GWG classification was established by Galjaard et al. (2013) based on only a few cases in the context of a small sample size. Our finding relating GWG trajectories to birth weight outcomes was also similar to a study of 651 overweight and obese women from Pittsburgh, which identified four GWG trajectories and reported that a consistently high GWG trajectory was associated with a 4.6-fold increased odds of LGA while a consistently low GWG trajectory was associated with a 1.2-fold increased odds of SGA, compared with women with adequate weight gains.8 The existing literature assessing the timing of GWG is small and has suggested that increasing 1st trimester9–11 as well as 2nd and 3rd trimester GWG9 is associated with a decreased odds of SGA, but an increased odds of LGA. Importantly, in our analysis, we observed an association between 1st trimester GWG and birth weight outcomes only when low or high GWG tracked into the 2nd/3rd trimesters. In addition, our findings build on this literature by utilizing a longitudinal approach to inform how the entire trajectory of GWG indicates risk for birth weight outcomes, as opposed to assessing trimester-specific gains as independent time-periods.

Clinical guidance regarding caloric intake is an important factor linked to actual maternal weight gain. 22 Prospective monitoring could improve early identification of a poor (low or high) weight gain trajectory and then serve as a prompt for clinicians to refer high-risk women to registered dietitians to counsel on lifestyle to potentially help reach optimal weight gain and with the goal of improving obstetric outcomes. Unfortunately, evidence suggests that clinicians infrequently provide any or accurate weight gain advice.22, 23 While the IOM recommended lower total GWG for overweight and obese women, we found that pre-pregnancy BMI did not modify the association between GWG trajectory and birth weight outcomes. Furthermore, after excluding complicated pregnancies, the reference trajectory remained unchanged and was not associated with adverse birth weight outcomes, which could support the reference trajectory as an optimal pattern for maternal and infant outcomes. Future research should address the causal link between modifying weight gain and improved birth weight outcomes and expand our findings to include long-term maternal and child health outcomes.

Given that our study is observational, we cannot determine a causal link between a modified GWG trajectory from the 1st to 2nd/3rd trimesters and a reduced risk of aberrant birth weight outcomes. Due to a small sample size, we were unable to estimate the risk of LGA by some high GWG tracking combinations and stratified analyses. The identified trajectories were limited by the reliance on self-reported pre-pregnancy weight, the accuracy of which may vary by maternal characteristics, although evidence suggests BMI remains accurately classified in 85% of pregnancies24 and recalled pre-pregnancy weight is often used in clinical practice enhancing the utility of our findings. Furthermore, the birth weight reference used to calculate SGA and LGA was comprised of mostly White women and applied to a racially diverse cohort. Another limitation of this study is the lack of long-term outcomes such as postpartum weight retention, child cognitive development, and metabolic profiles to assess the long-term health implications of GWG patterns. The inclusion criteria for the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies were limited by design to healthy women with a lower limit BMI of 19.0; therefore, we cannot make inferences about underweight women or women with general health complications. Limitations of our study reflect the observational design, including potential bias from the inclusion/ exclusion criteria used for cohort selection. As our aim was to assess GWG trajectories in a low risk healthy cohort, our findings might not be generalizable to higher risk obstetrical populations. Also, our study only assessed GWG, but not caloric intake or nutrition directly. Yet, the major advantage of our study was the inclusion of a racially and geographically diverse cohort of healthy women enabling us to identify patterns of weight gain unaffected by health conditions prior to pregnancy. This study was also strengthened by its longitudinal design with an average of 15 weight measurements per women, which increased the precision of estimated GWG trajectories. The use of a latent trajectory model allowed for a data-driven approach to identify clusters of weight gain. In addition, the inclusion of SGA plus neonatal morbidity and SGA<5th percentile provide insight into the potential risk of pathologically small infants associated with low or high GWG trajectories, although this finding is limited by a small sample size. Lastly, our study extends the current literature by highlighting the prevalence and implications of GWG tracking from the 1st to 2nd/3rd trimesters.

In conclusion, our findings are reassuring for women who experience weight loss or excessive weight gain in the first trimester. Achieving a reference trajectory in the 2nd/3rd trimester will normalize their risk of SGA and LGA. However, the risk of SGA and LGA is significantly increased if they gain weight below or above the reference trajectory in the 2nd/3rd trimester. Early clinical recognition of a poor GWG trajectory may help to detect at-risk pregnancies and serve as a prompt to discuss optimal weight gain, but ultimately, low or high 2nd/3rd trimester GWG presents a significant added risk for adverse birth weight outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the intramural program at Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and included ARRA funding (Contract numbers: HHSN275200800013C; HHSN275200800002I; HHSN27500006; HHSN275200800003IC; HHSN275200800014C; HHSN275200800012C; HHSN275200800028C; HHSN275201000009C).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Paper presentation: Preliminary results were presented during the Society for Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology conference in Miami on the 19th–20th of June 2016.

References

- 1.Rasmussen K, Yaktine A. Weight gain during pregnancy: Reexamining the guidelines. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies; Number of pages. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams B, Carmichael S, Selvin S. Factors associated with the pattern of maternal weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:170–6. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00119-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmichael S, Abrams B, Selvin S. The pattern of maternal weight gain in women with good pregnancy outcomes. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1984–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hickey CA, Cliver SP, McNeal SF, Hoffman HJ, Goldenberg RL. Prenatal weight gain patterns and birth weight among nonobese black and white women. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:490–6. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutcheon JA, Bodnar LM, Joseph KS, Abrams B, Simhan HN, Platt RW. The bias in current measures of gestational weight gain. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26:109–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galjaard S, Pexsters A, Devlieger R, et al. The influence of weight gain patterns in pregnancy on fetal growth using cluster analysis in an obese and nonobese population. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:1416–22. doi: 10.1002/oby.20348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narayanan RP, Weeks AD, Quenby S, et al. Fit for Birth - the effect of weight changes in obese pregnant women on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a pilot prospective cohort study. Clin Obes. 2016;6:79–88. doi: 10.1111/cob.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catov JM, Abatemarco D, Althouse A, Davis EM, Hubel C. Patterns of gestational weight gain related to fetal growth among women with overweight and obesity. Obesity. 2015;23:1071–78. doi: 10.1002/oby.21006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Margerison-Zilko CE, Shrimali BP, Eskenazi B, Lahiff M, Lindquist AR, Abrams BF. Trimester of maternal gestational weight gain and offspring body weight at birth and age five. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1215–23. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diouf I, Botton J, Charles MA, et al. Specific role of maternal weight change in the first trimester of pregnancy on birth size. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10:315–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sekiya N, Anai T, Matsubara M, Miyazaki F. Maternal weight gain rate in the second trimester are associated with birth weight and length of gestation. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007;63:45–8. doi: 10.1159/000095286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buck Louis GM, Grewal J, Albert PS, et al. Racial/ethnic standards for fetal growth: the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:449 e1–49 e41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duryea EL, Hawkins JS, McIntire DD, Casey BM, Leveno KJ. A revised birth weight reference for the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:16–22. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM. Distinguishing pathological from constitutional small for gestational age births in population-based studies. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:653–8. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sovio U, White IR, Dacey A, Pasupathy D, Smith GC. Screening for fetal growth restriction with universal third trimester ultrasonography in nulliparous women in the Pregnancy Outcome Prediction (POP) study: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2015;386:2089–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00131-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longo S, Bollani L, Decembrino L, Di Comite A, Angelini M, Stronati M. Short-term and long-term sequelae in intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:222–5. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.715006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg A. The IUGR newborn. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32:219–24. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giapros V, Drougia A, Krallis N, Theocharis P, Andronikou S. Morbidity and mortality patterns in small-for-gestational age infants born preterm. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:153–7. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.565837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McIntire DD, Bloom SL, Casey BM, Leveno KJ. Birth weight in relation to morbidity and mortality among newborn infants. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1234–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904223401603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King JR, Korst LM, Miller DA, Ouzounian JG. Increased composite maternal and neonatal morbidity associated with ultrasonographically suspected fetal macrosomia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:1953–9. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.674990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–57. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cogswell ME, Scanlon KS, Fein SB, Schieve LA. Medically advised, mother’s personal target, and actual weight gain during pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1999;94:616–22. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lucas C, Charlton KE, Yeatman H. Nutrition advice during pregnancy: do women receive it and can health professionals provide it? Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:2465–78. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunner Huber LR. Validity of self-reported height and weight in women of reproductive age. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11:137–44. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.