Abstract

Comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use disorders (SUD) commonly co-occur and is associated with a more complex clinical presentation with poorer clinical outcomes when compared with either disorder alone, and untreated PTSD can predict relapse to substance abuse. A number of integrated treatment approaches addressing symptoms of both PTSD and SUD concurrently demonstrate that both disorders can safely and effectively be treated concurrently. However, attrition and SUD relapse rates remain high and there is need to further develop new treatment approaches. Innovative approaches such as mindfulness meditation (MM) successfully used in the treatment of SUD may offer additional benefits for individuals with SUD complicated with PTSD. Specifically, Mindfulness-based Relapse Prevention (MBRP) integrates coping skills from cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention therapy with MM practices, raising awareness of substance use triggers and reactive behavioral patterns, and teaching skillful coping responses. Here we present the design and methods for the “Mindfulness Meditation for the Treatment of Women with comorbid PTSD and SUD” study, a Stage 1b behavioral development study that modifies MBRP treatment to address both PTSD and SUD in a community setting. This study is divided into three parts: revising the existing evidence-based manual, piloting the intervention, and testing the new manual in a randomized controlled pilot trial in women with comorbid PTSD and SUD enrolled in a community-based SUD treatment program.

Keywords: mindfulness-based relapse prevention, PTSD, SUD, behavioral therapy development, community research

1. Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)1, a chronic condition that develops following an extremely distressing traumatic event, is characterized by a set of symptoms resulting in significant functional impairment [1]. PTSD can often co-occur with substance use disorders (SUD), which are associated with poorer clinical outcomes than PTSD or SUD alone [2–7]. Women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with PTSD as compared to men, [8–10], so women-only community groups provide an emotionally safe and supportive environment that allows women to address sensitive issues such as domestic violence and victimization [11–15].

A number of integrated treatment approaches addressing symptoms of both PTSD and SUD concurrently have been explored in the past decade, including integrated treatments using exposure techniques for PTSD and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for SUD that have shown promise in improving both PTSD and SUD [16,17].

As both PTSD and SUD have been conceptualized as disorders of emotional dysregulation [18], disrupted emotional regulation and intolerance to negative internal and external experiences may be an important mediating factor between trauma exposure and subsequent SUDs. Researchers have found that distress tolerance was inversely associated with PTSD symptom severity in a group of trauma exposed cocaine dependent adults [19]. Another study in male veterans with comorbid PTSD and SUD showed a similar relationship between distress tolerance and PTSD symptom severity, particularly the intrusive thoughts and hyperarousal symptoms [20]. Mindfulness meditation (MM), a self-directed practice of intentionally attending to present-moment experiences (physical sensations, perceptions, affective states, thoughts and imagery) [21–23], has been shown to lead to better emotional processing and thus, improved emotion and self-regulation skills [24–26]. MM may provide a way for individuals with PTSD and SUD to experience a greater sense of control in relation to cravings triggered by trauma-related intrusive thoughts, memories and sensations. Individuals able to modulate these internal experiences may be less emotionally reactive and less prone to relapse related to escape/avoidance of distressing symptoms. Experiencing repeated exposure to PTSD and SUD triggers through MM without the associated emotional or behavioral reactivity, individuals practicing MM may habituate to these experiences resulting in diminished trauma symptoms and craving.

Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP) integrates coping skills from cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention therapy with MM practices, raising awareness of substance use triggers and reactive behavioral patterns, and teaching skillful coping responses [27]. Although MM interventions have shown promise in reducing symptoms of PTSD, there are no studies investigating MM in patients with comorbid PTSD and SUD, particularly in women who represent a high percentage of patients being treated in community programs.

This study attempts to fill the gap in research by investigating an adapted MBRP treatment to address both PTSD and SUD in a community-based treatment setting. A description of this behavioral therapy development study is presented, including the process of adapting an existing intervention, design and methodology of the pilot intervention, outcome measures used, data analysis, and safety precautions.

2. Methods and study design

2.1 Study overview

This study is a behavioral development 8 week, Stage 1b, single site study that seeks to modify an existing evidence-based treatment targeting SUD, MBRP, to address both PTSD and SUD in a community-based treatment setting. The primary purpose of the study intervention is to evaluate the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of an adapted MBRP in combination with treatment as usual (TAU) as compared to TAU alone for women with comorbid PTSD and SUD in a community-based SUD treatment program. The execution of the project consists of training/certifying the community therapists in the MBRP intervention, piloting the intervention in 2 patient groups, revising the manual to address PTSD symptoms, and testing the revised manual in a randomized controlled pilot trial that compares MBRP/TAU to TAU alone in 80 women enrolled in intensive community SUD treatment.

The majority of the modifications for the manual occur before (based on theoretical rationale, previous research) and after the pilot groups. The revision is an ongoing process and based on observations of the pilot sessions, interviews with therapists and participants, and discussions with the developer of the manual. Once the randomized control trial (RCT) is started the adaptations that have been made are incorporated, however, further adaptations can be made based on participant responses, attrition and/or adverse events. In this phase of the study, the RCT is not to test the effectiveness of the intervention but rather to assess the feasibility, safety and preliminary efficacy of the intervention. If successful, the behavioral development grant is followed by a larger randomized effectiveness trial.

Process assessments include measures of manual adherence, therapist competence, therapeutic/patient alliance and therapist/patient acceptability and satisfaction. Comprehensive evaluation on measures of MM, PTSD symptom severity, and substance use outcomes are done at baseline, periodically at 8 weekly visits throughout the intervention, post treatment, and at the 3 and 6 months post-treatment visits. Changes in emotion regulation and components of MM (attention, awareness to present moment and acceptance) will be explored to determine the intervention impact on PTSD symptoms, craving and substance use. If promising, results from this pilot study will provide effect size estimation for a larger Stage II randomized clinical trial. This pilot project will also test the feasibility of training and fidelity monitoring procedures for community therapists and assess acceptability, knowledge and adherence/competence.

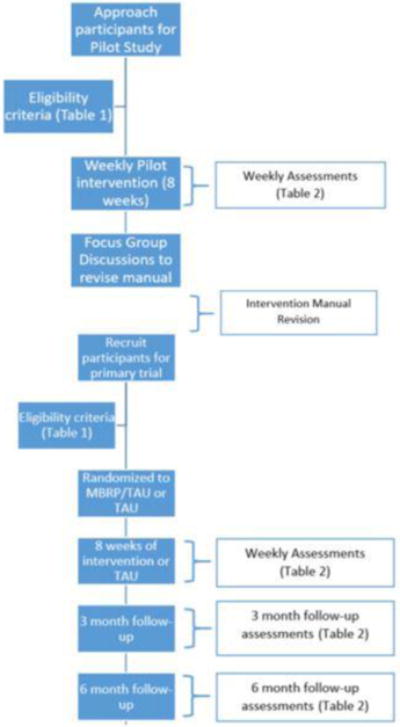

A brief overview of the study protocol is shown in Figure 1. In short, a small randomized pilot study will mimic the study design of the primary protocol in 3–6 women per group. Careful monitoring of participants during this phase will help address questions concerning the best match of trauma related components with the MBRP techniques. Weekly monitoring of PTSD, emotion regulation, craving and substance use will provide information concerning the timing, impact and duration of the intervention effects. After the final pilot group session, participants are invited to attend a focus group to provide feedback regarding interest, acceptability, benefits/usefulness, duration and timing of intervention in the treatment program and ability/willingness to practice meditation outside of the sessions. Specific adaptations to the revised manual are based on observations of the taped MBRP sessions, qualitative data from the focus groups and feedback from the community therapists. Recruitment, attrition, participant feedback, home practice completion, helping alliance questionnaire are part of the feasibility. The therapists’ acceptance, ease of delivery and belief that participants benefit from the intervention is another component. An innovative aspect to this intervention is that it is conducted in a front line community program and if successful, dissemination and adoption become less of a challenge.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram

Following completion of the pilot therapy and manual adaptation phase of the study, a randomized control phase will be implemented. In this phase of the study, the active intervention group receives MBRP group therapy adapted to address PTSD plus TAU for 8 weeks.

2.2 Randomization

Once participants are deemed eligible, they are randomized to either the intervention (MBRP/TAU) or control (TAU only) group. Urn randomization is used to assign participants [28] in a 1:1 allocation while stratifying treatment assignment on two critical variables; 1) baseline levels of alcohol and/or SUD use intensity (cutoff of 10 or more days of alcohol and/or SUD use excluding nicotine in the 30 days prior to clinical enrollment) and 2) PTSD symptom severity (cutoff of a Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) score of ≥ 33). Days of drug use and severity of PTSD symptomology as measured by the CAPS at baseline (pre-study involvement) are a likely prognostic factors on the substance use frequency and severity outcomes [16,29–32], and as such, are controlled during randomization.

2.3 Study Efficacy Outcomes

To best assess the efficacy of treatment with MBRP/TAU as compared to TAU only on the primary study outcomes, the primary outcome assessments would be examined over the final 30 days of treatment intervention as well as durability assessment at the 3 and 6 month follow-up visits. There are two primary study outcomes. The first is the effective reduction in PTSD symptom severity through the total score on the CAPS [33] at the end of treatment (after 8 weeks) between the two study groups. The changes in CAPS scores will be assessed at study weeks 4 and 8 during the intervention, and again at the 3 and 6 month follow-up visits. The week 4 assessment is designed to determine tolerability and safety half way through the intervention. This data may also provide a dose response outcome or determine if there are any benefits after half the sessions are completed. In addition, for women who leave the program prior to completion, we will have some primary outcome data.

The second primary study outcome is the effective reduction in the proportion of days using alcohol/substances during the final 30 days of treatment compared to the 30 days prior to study entry as measured by the Timeline Followback (TLFB) [34–36], with abstinence verified by urine drug screen (UDS). UDS is performed with the 7 panel on-site rapid drug test (clia-waived) that detects the presence of cocaine, opiates, methadone, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), methamphetamine, benzodiazepines and oxycodone. In order to assess the frequency and intensity of substance use, the TLFB was used to collect substance use between study visits and at follow-up. Changes in substance use frequency and substance use abstinence at the close of the treatment phase (30 days) of the study combined become the second primary SUD outcome.

Secondary study outcome measures are assessed periodically during the study intervention and follow-up. In addition to the CAPS as a measure of PTSD symptomology, the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5), and the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale-Self Report (PSS-SR) will be assessed during the study. The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) assesses lifetime exposure to trauma [37], while the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale-Self Report (PSS-SR) is a 21-item self-report inventory, which assesses the frequency and severity of PTSD symptoms corresponding to the diagnostic criteria listed in the DSM-V [38]. The PSS-SR is monitored weekly throughout the intervention to assess within treatment PTSD symptom severity and adverse events (symptom worsening). Changes of the quantity of use of alcohol/substances measured by the TFLB during the final 30 days of treatment will also be collected for a secondary outcome.

2.4 Study Interventions

Treatment as Usual (TAU)

For this study, the TAU is approximately 12 weeks long and provides groups and classes focused on psychoeducation, relapse prevention, 12-step and parenting up to 20 hour/four days a week program. The program includes weekly 90 minute Seeking Safety (SS) groups, a cognitive behavioral integrated trauma intervention. Women meet individually with a counselor prior to SS group entry. The SS group will provide a control intervention for the study.

Mindfulness Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP)

Mindfulness meditation (MM), with roots in Eastern philosophy, has been explored in stress-related medical conditions, depression, anxiety and addictions in clinical and non-clinical populations [39–43]. MM provides a way for individuals with PTSD and SUD to experience a greater sense of control in relation to craving triggered by trauma-related intrusive thoughts, memories and sensations. Individuals able to modulate these internal experiences are less emotionally reactive or prone to relapse in order to escape/avoid distressing symptoms. During MM practice, when distressing trauma memories/thoughts emerge into consciousness, no attempt is made to change or suppress them; rather, it is simply noticed as one part of a broader range of experiences in that moment. MBRP integrates coping skills from cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention therapy with MM practices, raising awareness of substance use triggers and reactive behavioral patterns, and teaching skillful coping responses [27].

The MBRP group therapy intervention contains one introductory and 8 weekly group sessions. These sessions are integrated into the standard TAU program, and replaces 9 TAU SS group sessions. The evidence supporting MBRP for the treatment of SUD comes from a recent large randomized control study (n = 286) comparing MBRP, relapse prevention (RP) and TAU delivered as aftercare following SUD intensive treatment. Both MBRP and RP had greater reductions in drug use and heavy drinking than TAU at 6 month follow-up (p<0.5). At 12 months, MBRP resulted in a 31% greater reduction in drug use days among those participants who used (IRR = .69; p<.05) and a greater probability of not engaging in heavy drinking (OR 1.51 p<.05) than RP participants [44]. MM has also been shown to reduce PTSD symptoms in individuals with and without SUD [25,45,46]. Because treatment attrition and relapse is problematic in this complex population, the MBRP will be initiated earlier in the treatment program. Participants will start the MBRP groups after one week in their standard treatment program. Patients typically attend other program groups, including cognitive behavioral and seeking safety, upon enrollment in treatment services. Addressing PTSD early in SUD treatment can potentially improve attrition and relapse related to PTSD triggers.

2.5 Training

Master’s level therapists from the community program receive training in the MBRP conducted by the expert trainer and developer/author of the MBRP manual [47]. Training includes (1) didactic review of intervention-specific theory (cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness meditation techniques); (2) observation and practice within trainer-conducted mock intervention sessions; and (3) trainee-conducted mock intervention sessions. Upon completion of the training and satisfactory observed role play experience, the therapists pilot the intervention in 2 patient groups with approximately 6 patients per group. All therapy sessions are audiotaped and reviewed by the expert trainer using fidelity measures developed for the MBRP intervention [48]. Therapists’ certification includes completion of all the sessions at a level of proficiency of at least a 3 on a scale of 1=low to 5=high on item ratings consisting of key MBRP concepts, therapist style/approach and overall performance. A community therapist supervisor, the PI, and expert trainer will obtain inter-rater reliability on the MBRP- Acceptance and Competency (MBRP-AC) fidelity scale [48]. This fidelity scale is also modified to include the manual adaptations.

Therapists receive ongoing weekly supervision and training throughout the project to reinforce and sustain their skills in therapy delivery. These methods parallel those used to sustain integrity in other integrated treatment outcome research projects at our sites. Any therapist “drift” is addressed in supervision. The purpose of the pilot phase is to assess feasibility and acceptability of the intervention both from the clinician and participant perspective. This includes the ability and ease at which the therapists deliver the intervention with fidelity. This is the typical process of this phase of a behavioral development grant [49]. Participants in the pilot phase attend a focus group following the eight sessions conducted by the principal investigator.

During the randomized component of the project all sessions will be audiotaped and randomly selected sessions (approximately 1/3 for each therapist) from each group will be evaluated using the MBRP-AC Scale.

3. Participant recruitment and eligibility

3.1 Participant Recruitment

Recruitment of participants primarily takes place from the community program women’s Intensive outpatient (IOP) and residential treatment at the Charleston Center (Charleston, SC) where women attend the same treatment program. The Charleston Center is adjacent to and has a long standing relationship with the Medical University of South Carolina. This program is the only program in the city/county that offers intensive SUD services for women. In addition, women are referred to this program from all over the state. Research staff approach patients after clinical intake admission and referral from their primary counselor to inform them about the study and elicit interest. If interested and pre-screen is positive, an informed consent is obtained by the research staff. Interested potential participants are screened for major inclusion/exclusion criteria including age, substance use, and history of trauma and psychiatric/health/medication status. The research staff are located on site and interact frequently with clinic staff. The clinic staff involved in the study will include 3 therapists and a clinical program director. Clinical staff meetings where patient treatment planning and progress are discussed occur on a weekly basis and provide opportunity to discuss study recruitment and potential participants.

3.2 Participant eligibility

Details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the target population are shown in Table 1, which includes women between 18 and 65 years of age enrolled in the intensive community SUD treatment. Exclusion criteria are crafted to exclude potential participants at higher risk for adverse effects, including those with severe co-occurring medical or psychiatric disorders as they may be more likely not to benefit from the intervention and/or to be hospitalized during the course of the study. Patients with suicidal or homicidal, psychotic or exhibit cognitive deficits are excluded. The exclusion criteria are minimal as these patients represent the typical patient that presents for treatment and subsequently engage in other clinic groups. Patients can be withdrawn from the study and referred for more intensive treatment if there are: Increases in alcohol or drug use leading to the need for a more intensive level of care (i.e., medical detoxification, inpatient); active suicidal or homicidal ideation; inability to return for therapy sessions due to incarceration or hospitalization lasting longer than five weeks; or inability to manage psychiatric symptoms within the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the study (i.e., need for the initiation of maintenance psychotropic medications; development of psychosis). If it is determined, based on clinical criteria, that a participant needs to be started on maintenance medications for anxiety, mood or psychotic symptoms during the course of the study, they can be discontinued from the treatment trial.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Eligible Participants

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Women between 18 and 65 years of age enrolled in the intensive outpatient and residential program treatment | 1. Current primary psychotic or thought disorder (i.e. Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, mania), major depression with suicidal ideation, dissociative identity disorder and/or homicidal ideations |

| 2. Able to comprehend English | 2. Present a serious suicide risk, such as those with severe depression, or who are likely to require hospitalization during the course of the study |

| 3. Meets DSM-V criteria for current alcohol or substance use disorder and have used alcohol/substances in the 60 days prior to clinic treatment entry | 3. In ongoing therapy for PTSD either within or outside of the community treatment program, who are not willing to discontinue these therapies for the duration of the study therapy |

| 4. Meets DSM-V criteria for current PTSD with a score of > 25 on the CAPS | 4. Unstable medical condition or one that may require hospitalization during the course of the study |

| 5. Participants may also meet criteria for a mood or anxiety disorder. However, participants on psychotropic medications for a mood or anxiety disorder must have been stabilized on medications for at least 4 weeks before therapy initiation | 5. Women who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant |

| 6. Able to adequately provide informed consent and function at an intellectual level sufficient to allow accurate completion of all assessment instruments | |

| 7. Willing to commit to 8 therapy sessions, baseline, weekly, and follow-up assessments |

3.3 Assessment Timings

All assessment and schedules are reported in Table 2. Primary screening assessments include the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) 7.0, the Time Line Follow Back (TLFB), the Life Event Checklist (LEC), the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) interview, urine pregnancy test, and urine drug screen (UDS). If the participant continues to meet eligibility, a baseline assessment is scheduled. The women are breathalyzed for alcohol per program policy. Any women with observed behavioral indicators of intoxication (i.e. slurred speech, drowsiness, overt disinhibition, euphoria, ataxia) are not permitted to attend groups.

Table 2.

Assessment Schedule

| Screening | Treatment (weeks 1–8) | Follow-Up | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screen | Base | W 1 | W 2 | W 3 | W 4 | W 5 | W 6 | W 7 | W 8 | Months 3 and 6 | |

| MINI | X | ||||||||||

| Urine pregnancy | X | ||||||||||

| UDS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| LEC | X | ||||||||||

| ASI-Lite | X | X | X | ||||||||

| CAPS | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| TLFB | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| UDS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| PSS-SR | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| OCDS-R-Brief | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| FFMQ-SF | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| CAMS-R | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| DERS | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| MAAS | X | X | X | X | |||||||

4. Data Management and Analytic Approach

4.1 Analytic Approach

The primary outcome measures for the efficacy portion of this study are 1) the effective reduction in PTSD symptom severity through the total score on the CAPS at the end of treatment (after 8 weeks) between the two study groups and 2) the effective reduction in the proportion of days using substances as well as abstinence during the final 30 days of treatment as measured by the TLFB (abstinence verified by UDS). In addition, secondary endpoints include CAPS scores at week 4 and the 3 and 6 month post-intervention follow-up visits, LEC-5, and PSS-SR. OCDS-R, ASI-Lite, DERS, MAAS, FFMQ-SR, and CAMS-R will be used to gain insight into potential effect modification and mediation. Secondary analyses include the proportion of days using alcohol/drugs, craving, psychosocial functioning and emotional regulation at 3- and 6- month follow-ups.

The primary aims of the proposed study is to assess the feasibility of MBRP in the proposed population and to estimate effect sizes and their 95% confidence intervals in order to inform a larger study sample size calculation for a clinically relevant treatment effect. Estimates of between group difference in CAPS score and substance use frequency and the associated variances will be calculated using model based estimates and their 95% confidence limits. PTSD Symptoms (CAPS, PSS-SR) as well as substance use quantification (TLFB, % days using) will be examined using a linear mixed effects model to estimate the treatment effect and variance in the change from baseline to the end of treatment and 3- and 6- month follow-ups. Effect modification of secondary measures of craving, mindfulness and emotional regulation on the primary outcomes of PTSD symptom severity and substance use will be tested with interaction terms included in the models. The cohort grouping of participants will be taken into account in the analysis model through random cluster effects that will account for the dependency that may exist across participants within a common cluster. Normality of the model residuals will be assessed (where appropriate) both graphically (Q-Q plots) and through the use of statistical normality tests (Shapiro-Wilk test). Deviations from normality will be corrected with alternate functional forms of the dependent variable (natural logarithm or square root transformations). Where normality cannot be reasonably obtained, non-parametric models will be used to test the hypothesis. Generalized Linear Mixed Effects Models (GLMMs) will allow us to model clustered data that may exhibit non-Gaussian properties while maintaining the dependency of the within cohort data using various distributions. Treatment effects estimated using the results of the general linear models in combination with the confidence intervals of the variance will be used to estimate power for a larger efficacy clinical trial of MBRP for the treatment of comorbid PTSD/SUD.

4.2 Sample Size Calculations

This study is powered to assess the efficacy of MBRP/TAU versus TAU in the reduction of CAPS scores from baseline to the end of study treatment (8 weeks). In addition, the study aims to estimate the precision of the variance estimates by calculating effective differences and 95% confidence interval for the squared sample standard deviation of mean responses and their differences. In a similar study design, King et al found a clinically significant difference in CAPS score reductions following 8 weeks of mindfulness based cognitive therapy as compared to TAU in participants suffering from combat PTSD (Completers: Hedge’s g=1.01) [50]. We have assumed a 20% attenuation in the effect size for our intent to treat analysis (Hedge’s g=0.80). Under the assumption of equal group allocation (1:1) and independence of participant observations, a sample size of 25 participants per arm would be required to provide 80% power with a type 1 error rate of 5%. However, due to within cohort dependencies, the sample size is inflated to account for this correlation. Assuming a moderate within cohort correlation (ρ=0.1), and cohort sizes of 3 per group, we will require a sample size of n=30 per arm to maintain adequate power to detect the noted effect size in PTSD severity. With a similar attrition rate to the study assessing CAPS score and mindfulness cognitive therapy [50] of 25%, the final study sample size of n=80 participants (n=40 per group) would maintain adequate power to detect a meaningful difference at the conclusion of the study.

4.3 Missing Data and Attrition

Missing data in longitudinal studies can be a very problematic feature but can be mitigated through study design considerations. Attrition can introduce bias in the treatment group parameter estimate and reduce power, precision, and generalizability. Every attempt will be made to engage participants for the duration of the therapy period. Individuals will be considered drop-outs from treatment if they fail to attend therapy sessions for four consecutive weeks, in spite of attempts by phone and mail to engage them in treatment. Throughout the course of the study we will have adequate personnel to track participants, manage the scheduling of appointments, and have close supervision of therapy procedures. Research staff will gather locator information at baseline (i.e. phone numbers, contacts), which they will update on a weekly basis. Therapists and research assistants will be trained in the importance of this aspect of the protocol and in techniques used in other studies to enhance retention. We will also provide transportation or transportation reimbursement vouchers for fuel to minimize this potential obstacle and burden. Of note, the CC offers some free transportation as part of its women’s IOP clinical services. Comparable to other studies, compensation for time it takes for completion of assessments will be in the form of cash, vouchers or gift cards and includes the following: Participants will receive $35 for the baseline assessment; $10 for completion of weekly assessments, $25 for completion of week 4 assessments, $35 for completion of 8 week post intervention, $40 for the three month follow-up and $50 for the six month follow-up assessment. Thus, the total participants may receive for completion of all the study assessments is $245. Participants who are non-adherent or drop out of treatment will be invited to participate and receive compensation for completion of follow-up assessments.

However, these methods do not ensure that all data will be collected and appropriate analysis methods will be employed to accommodate missing data. Mixed-effects models using methods of maximum likelihood yield valid inferences assuming ignorable attrition (i.e., attrition is accounted for by covariates or the dependent variable measured prior to dropout. Maximum likelihood methods will be implemented to retrieve parameter estimates. Under the assumption of data missing at random, ML will produce consistent, efficient, and asymptotically normal estimates. We have assumed that attrition will occur, and the sample size of the study was modified to ensure that the power to detect treatment group differences is maintained. In addition, in keeping with the Intent to Treat Principle, we will make every effort to continue assessments for the entire course of randomized treatment, even among those who fail to adhere to randomized assignment or stop participating in the study assigned intervention.

5. Safety Monitoring and Considerations

Unlike other potential medications for both substance use disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder, the likelihood of adverse events with mindfulness based treatment is extraordinarily low. However, adverse events (AE) will be documented and monitored throughout the study and all events are followed to resolution or stabilization. All serious adverse events are reported immediately to the IRB and the federal funding agency. An adverse event (AE) is defined as any reaction, side effect, diagnosis or untoward event that either a) occurs during the course of the clinical trial and was not present at baseline; or b) was present at baseline and appears to worsen during the study. All AE’s will be assessed by the Principal Investigator or the co-Investigator (MD, Ph.D.) from baseline through the last follow-up assessment. During weekly assessments the research coordinator asks about AEs. In the event that the participant is experiencing a worsening of symptoms, the RC informs appropriate study and clinical staff. The PI, Co-I, and the participant’s study therapist determine if the AE places the participant at risk if study treatment is continued. The risks expected from trials employing behavioral interventions are presumed minimal relative to pharmacologic interventions. However, for this trial specifically, the population studied is a vulnerable population and possibly high risk given the nature of the disorders (i.e. SUD and PTSD). Study staff are trained to provide crisis intervention and referral as is standard operating procedure within the community center for such situations, should they become dangerous or life-threatening (i.e. suicidal ideation or attempts). The PI, Co-I (MD, Ph.D.) is available to respond to a need for consultation in order to fully assess untoward reactions or severe symptoms, including suicidality. Specific to this study, potential study-related AEs include 1) worsening of PTSD symptoms, 2) worsening of SUD symptoms, and 3) worsening of depressive symptoms. For this reason, participants are assessed weekly on current symptom measures of PTSD, SUD and depression (PSS-SR, TLFB) in order to observe any signs of severe symptoms of SUD, PTSD and depression. Additionally, participants are advised to observe any signs of worsening PTSD, SUD and depression symptoms and to discuss these with study staff. If the level of symptom worsening becomes dangerous or life threatening (e.g. drug overdose or suicidal ideation or attempt, any symptom worsening requiring inpatient hospitalization), further intervention, documentation, and reporting are required. A data safety and monitoring board (DSMB) has been created to monitor the overall participant safety, the rate and severity of adverse events, and the validity and integrity of the data. The panel includes 3 researchers with experience in treating patients with PTSD and/or SUD. The board can be called at any point if needed for unexpected AEs, etc. Modifications are made in the procedures and/or the protocol if necessary based on the recommendations of the board.

6. Discussion

Behavioral therapy development is a process involving several stages that include application of behavioral principles to generate or refine an existing intervention, creating or revising therapy manuals, initial training and piloting, further manual revisions and efficacy testing [49]. This paper describes the design and methods of a behavioral therapy development study that modifies an existing treatment, MBRP, to be used in a population of women who are affected by co-occurring PTSD and SUD. The complex nature of this comorbidity and poor treatment outcomes warrant improved innovative treatment approaches [6,7]. The study will evaluate the utility of a potentially effective psychosocial intervention, MBRP added to TAU, in reducing PTSD symptom severity and alcohol/substance use as compared to TAU alone. Women randomized to TAU alone attend an integrated trauma informed group intervention that is a regular part of the community treatment program. The MBRP intervention replaces the trauma informed group for those women randomized to the experimental group. This is the first study to incorporate MBRP in a community SUD treatment program to target both PTSD and SUD symptoms. PTSD components include discussing normal reactions to trauma and the relationship between trauma symptoms and substance use. A recent study found that mindfulness mediates the relationship between PTSD symptoms and SUD severity such that those with more severe PTSD symptoms and substance use had low scores on measures of mindfulness. This suggests that altering one’s relationship to these symptoms through nonjudgmental awareness and acceptance can improve PTSD symptoms and SUD [51].

Avoidant coping is a functional negative reinforcer that only perpetuates the PTSD symptom and substance use relapse cycle. Substance use as an avoidant strategy is replaced with mindfulness meditation practices. Women learn to mindfully approach versus avoid uncomfortable trauma related feelings, thoughts and memories. The women in this study also receive recordings of guided formal meditation exercises to reinforce practice at home. Home exercise practice has been associated with greater reductions in alcohol/drug use and cravings [52].

Although psychosocial interventions present minimal risks, assessing intervention safety is also an important part of behavioral therapy development. Careful monitoring for adverse events can inform whether the treatment is beneficial or deleterious to certain patients receiving the intervention. Other safety considerations include the timing of the intervention in the course of the treatment program and the impact of continued use.

This study is designed such that involvement of the community therapists and participants provide relevant information needed for manual revisions. Adaptations to the MBRP manual are systematically made by observations of group behaviors during the piloting of the intervention, focus groups with participants and therapists’ feedback. Feasibility, acceptability, usefulness, timing of intervention within the treatment program and ability/willingness to practice meditation outside of the sessions are important considerations. Thus, the community program is invested in the intervention from the start and is part of the team developing and adapting the intervention. This buy-in process can increase the likelihood of adopting the intervention once the research is complete. This study exemplifies the process involved in behavioral therapy development. Adaptations made to the MBRP for implementation in a community setting can increase the likelihood of successful adoption, as well as provide another treatment option for women with comorbid PTSD and SUD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01 DA040968]

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder

SUD: substance use disorders

CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy

MM: mindfulness meditation

MBRP: mindfulness-based relapse prevention

TAU: treatment as usual

RP: relapse prevention

SS: Seeking Safety

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady KT, Pearlstein T, Asnis GM, Baker D, Rothbaum B, Sikes CR, Farfel GM. Efficacy and safety of sertraline treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:1837–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1837. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10770145 (accessed January 5, 2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown P. Outcome in female patients with both substance use and post-traumatic stress disorders. Alcohol Treat Q. 2000;18:127–135. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harned MS, Najavits LM, Weiss RD. Self-harm and suicidal behavior in women with comorbid PTSD and substance dependence. Am J Addict. 2006;15:392–5. doi: 10.1080/10550490600860387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Najavits LM, Weiss RD, Shaw S. A clinical profile of women with PTSD and substance dependence. Psychol Addict Behav. 1999;13:90–104. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ouimette P, Coolhart D, Funderburk JS, Wade M, Brown PJ. Precipitants of first substance use in recently abstinent substance use disorder patients with PTSD. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1719–27. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Read JP, Brown PJ, Kahler CW. Substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders: symptom interplay and effects on outcome. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1665–72. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, Davis GC. Previous Exposure to Trauma and PTSD Effects of Subsequent Trauma: Results From the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:902–907. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortina LM, Kubiak SP. Gender and posttraumatic stress: sexual violence as an explanation for women’s increased risk. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:753–9. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Najavits LM, Weiss RD, Shaw SR. The link between substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder in women. A research review. Am J Addict. 1997;6:273–83. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9398925 (accessed January 6, 2017) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashley OS, Marsden ME, Brady TM. Effectiveness of substance abuse treatment programming for women: a review. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:19–53. doi: 10.1081/ada-120018838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bloom B. Why focus on programming for women offenders? Forum Correct. 1998;11:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenfield SF, Back SE, Lawson K, Brady KT. Substance Abuse in Women. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:339–355. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grella CE. From generic to gender-responsive treatment: changes in social policies, treatment services, and outcomes of women in substance abuse treatment. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;(Suppl 5):327–43. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400661. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19256044 (accessed January 5, 2017) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Prendergast ML, Messina NP, Hall EA, Warda US. The relative effectiveness of women-only and mixed-gender treatment for substance-abusing women. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;40:336–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brady KT, Dansky BS, Back SE, Foa EB, Carroll KM. Exposure therapy in the treatment of PTSD among cocaine-dependent individuals: preliminary findings. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;21:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00182-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11516926 (accessed January 5, 2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mills KL, Teesson M, Back SE, Brady KT, Baker AL, Hopwood S, Sannibale C, Barrett EL, Merz S, Rosenfeld J, Ewer PL. Integrated exposure-based therapy for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;308:690–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watt DF. Consciousness, emotional self-regulation and the brain: Review article. J Conscious Stud. 2004;11:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vujanovic AA, Rathnayaka N, Amador CD, Schmitz JM. Distress Tolerance. Behav Modif. 2016;40:120–143. doi: 10.1177/0145445515621490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinci C, Mota N, Berenz E, Connolly K. Examination of the relationship between PTSD and distress tolerance in a sample of male veterans with comorbid substance use disorders. Mil Psychol. 2016;28:104–114. doi: 10.1037/mil0000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabat-Zinn J, Massion AO, Kristeller J, Peterson LG, Fletcher KE, Pbert L, Lenderking WR, Santorelli SF. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:936–43. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing; NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7042457 (accessed January 6, 2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau MA, Grabovac AD. Mindfulness-Based Interventions: Effective for Depression and Anxiety: Evidence Supports Adjunctive Role for the Combination of Meditative Practices and CBT. Curr Psychiatr. 2009;8:39. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garland EL, Roberts-Lewis A, Tronnier CD, Graves R, Kelley K. Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement versus CBT for co-occurring substance dependence, traumatic stress, and psychiatric disorders: Proximal outcomes from a pragmatic randomized trial. Behav Res Ther. 2016;77:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rapgay L, Ross JL, Petersen O, Izquierdo C, Harms M, Hawa S, Riehl S, Gurganus A, Couper G. A Proposed Protocol Integrating Classical Mindfulness with Prolonged Exposure Therapy to Treat Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Mindfulness (N Y) 2014;5:742–755. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0231-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowen S, Chawla N, Collins SE, Witkiewitz K, Hsu S, Grow J, Clifasefi S, Garner M, Douglass A, Larimer ME, Marlatt A. Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention for Substance Use Disorders: A Pilot Efficacy Trial. Subst Abus. 2009;30:295–305. doi: 10.1080/08897070903250084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 1994;12:70–5. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7723001 (accessed January 6, 2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Back SE. Toward an Improved Model of Treating Co-Occurring PTSD and Substance Use Disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:11–13. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09111602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hien DA, Jiang H, Campbell ANC, Hu MC, Miele GM, Cohen LR, Brigham GS, Capstick C, Kulaga A, Robinson J, Suarez-Morales L, Nunes EV. Do treatment improvements in PTSD severity affect substance use outcomes? A secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial in NIDA’s Clinical Trials Network. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:95–101. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09091261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouimette PC, Ahrens C, Moos RH, Finney JW. Posttraumatic stress disorder in substance abuse patients: Relationship to 1-year posttreatment outcomes. Psychol Addict Behav. 1997;11:34–47. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.11.1.34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reed PL, Anthony JC, Breslau N. Incidence of drug problems in young adults exposed to trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: do early life experiences and predispositions matter? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1435–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blake D, Weathers F, Nagy L, Kaloupek D, Klauminzer G, Charney D, Keane T. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: The CAPS-1. Behav Ther. 1990;8:187–188. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sobell LC, Sobell M. A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Meas Alcohol Consum Psychosoc Biol Method. Humana Press; New Jersey: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobell LC, Sobell M. Alcohol consumption measures. In: Allen JP, Columbus M, editors. Assess Alcohol Probl A Guid Clin Res. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 1995. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobell LC, Sobell M. Handb Psychiatr Meas. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. Alcohol Timeline Followback (TLFB) pp. 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weathers F, Blake D, Schnurr P, Kaloupek D, Marx B, Keane T. The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foa E, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychol Assess. 1997;9:445–451. http://psycnet.apa.org/index.cfm?fa=buy.optionToBuy&id=1997-43856-013 (accessed January 9, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fjorback LO, Arendt M, Ørnbøl E, Fink P, Walach H. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy - a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:102–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roemer L, Orsillo SM. Expanding Our Conceptualization of and Treatment for Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Integrating Mindfulness/Acceptance-Based Approaches With Existing Cognitive-Behavioral Models. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2002;9:54–68. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.9.1.54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tacón AM, McComb J, Caldera Y, Randolph P. Mindfulness meditation, anxiety reduction, and heart disease: a pilot study. Fam Community Health. 2003;26:25–33. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200301000-00004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12802125 (accessed January 6, 2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Williams JM, Ridgeway VA, Soulsby JM, Lau MA. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:615–23. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.4.615. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10965637 (accessed January 6, 2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Clifasefi SL, Grow J, Chawla N, Hsu SH, Carroll HA, Harrop E, Collins SE, Lustyk MK, Larimer ME. Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:547–56. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Felleman BI, Stewart DG, Simpson TL, Heppner PS, Kearney DJ. Predictors of Depression and PTSD Treatment Response Among Veterans Participating in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction. Mindfulness (N Y) 2016;7:886–895. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0527-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Malley PG. In veterans with PTSD, mindfulness-based group therapy reduced symptom severity. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:JC9. doi: 10.7326/ACPJC-2015-163-12-009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bowen S, Chawla N, Marlatt GA. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for addictive behaviors : a clinician’s guide, Guilford Press. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chawla N, Collin S, Bowen S, Hsu S, Grow J, Douglass A, Marlatt GA. The mindfulness-based relapse prevention adherence and competence scale: development, interrater reliability, and validity. Psychother Res. 2010;20:388–97. doi: 10.1080/10503300903544257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rounsaville BJ, Carroll K, Onken L. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from Stage 1. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2001;8:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- 50.King AP, Erickson TM, Giardino ND, Favorite T, Rauch SAM, Robinson E, Kulkarni M, Liberzon I. A pilot study of group mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:638–45. doi: 10.1002/da.22104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bowen S, De Boer D, Bergman AL. The role of mindfulness as approach-based coping in the PTSD-substance abuse cycle. Addict Behav. 2017;64:212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grow JC, Collins SE, Harrop EN, Marlatt GA. Enactment of home practice following mindfulness-based relapse prevention and its association with substance-use outcomes. Addict Behav. 2015;40:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]